Displaying items by tag: Liam Hegarty

Conor O’Brien’s World–Girdling Saoirse Will Sail Again

The process towards re-creating Conor O’Brien’s famous Baltimore–built 42ft ketch Saoirse, in which he gained his place in international sailing’s Hall of Fame with the first circuit of the world by a small vessel south of the great capes in 1923-1925, has been quietly confirmed this week with the agreement of a well-resourced backer who for the moment prefers to remain anonymous. W M Nixon takes a fresh perspective on one of Irish sailing’s central stories.

Much and all as there was triumph and tribulation and then triumph again in Conor O’Brien’s sailing achievements, his personal life could be summed up as one of success and sadness. So could many lives. But as with most things to do with Conor O’Brien, success and sadness came on an epic scale – there was a monumental, sometimes tragic quality to it.

It is something which is inevitably going to receive more attention as the process of re-creating his remarkable little ship swings into action in Oldcourt near Baltimore. The Saoirse re-build is coming centre stage in West Cork as the great and lengthy project of re-building his 57ft 1926 ketch Ilen nears completion. Ilen will be launched next summer, and the quality of the workmanship of Liam Hegarty and his craftsmen in Oldcourt with this project will achieve the recognition it so richly deserves.

So too will the vision of Gary MacMahon of the Ilen Boatbuilding School in Limerick who inspired Ilen’s re-birth, which in turn has provided the credentials to make the re-creation of Saoirse something which is becoming very real. It has become so real that the new keel has already been cut and shaped, while enough bits and pieces have been retrieved in Jamaica from the wreck of Saoirse in her first incarnation to provide a real connection for the re-born boat. Meanwhile, next week will see the orders being placed for further consignments of the required timber.

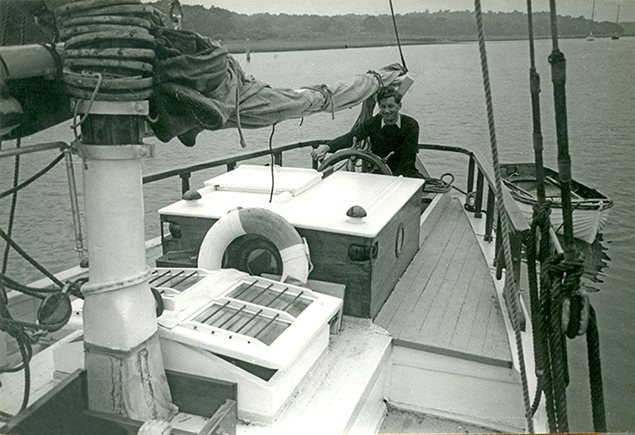

Conor O’Brien was at his most content when up in the mountains, or far out at sea. He is seen here at the helm of Saoirse in mid-ocean as she reels off the miles in her famous effortless style. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Conor O’Brien was at his most content when up in the mountains, or far out at sea. He is seen here at the helm of Saoirse in mid-ocean as she reels off the miles in her famous effortless style. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

The very idea of some day being able to sail on an exact replica of Saoirse, a replica which has retained the soul of the original vessel, is something which will fascinate anyone who has made even the most cursory study of what O’Brien achieved on his voyage, and in his design of this unique boat.

There are probably many more in Ireland who are tangentially aware of O’Brien through the fact that, with the ketch Kelpie, which he owned from 1911 to 1922, he was the junior partner with Erskine & Molly Childers’ Asgard in the gun-running to Howth and Kilcoole in 1914, with Kelpie’s cargo of 600 Mauser rifles being taken for the final stage to the Kilcoole landing aboard Sir Thomas Myles’ auxiliary-powered Chotah. But in terms of the world’s amateur sailing history, the 1914 gun-running pales into insignificance when set against the mighty circumnavigation of the little Saoirse in 1923-25.

It was the first major international voyage undertaken under the ensign of the new Irish Free State. Yet despite the new tensions which inevitably existed between the British establishment – particularly the British maritime establishment - with the nascent Irish state and those who created it and ran it, it was a pillar of the British maritime establishment who set the international tone in putting Conor O’Brien’s voyage with Saoirse in its proper and revered context.

These days the name of Claud Worth will only be known to those who are immersed in the details of the history of cruising and its development. But in the first thirty years of the 20th Century, Claud Worth – ophthalmic surgeon by day, seagoing guru for much of the rest of the time – was an authority in a league of his own.

A kindly authority, let it be said. And always a source of helpful advice, with suggestions which are still relevant today. Just recently, someone asked about how best to prepare a log for a cruising competition. The most useful response was to quote Claud Worth’s suggestions from 1910 about how you should gradually introduce the boat, her crew and the planned cruise as the story unfolds, to bring the reader along with you to share the experience, rather than have it hurled at them as a mass of indigestible statistics about mileages, wind strengths, and dealing with problems large and small.

Thus by the time Saoirse set off on her voyage, Claud Worth was the global authority in the world of log adjudication, and he found himself in the demanding position of assessing logs for the world’s senior cruising trophy, the Challenge Cup of the Royal Cruising Club.

This had been awarded on its inauguration in 1896 to Belfast doctor, Howard Sinclair, for a cruise round Ireland in the 6-tonner Brenda. But by 1923, the scope of the several major cruises put forward for the Challenge Cup had expanded enormously from round Ireland voyages. Yet in his adjudications, Claud Worth unhesitatingly awarded the Challenge Cup for 1923, 1924 and 1925 to the former gun-runner as Saoirse’s voyage round the world went on to various ports, through the Great Southern Ocean, and back into Dun Laoghaire exactly two years to the day since he first departed on what had been casually described as “a voyage to New Zealand for some mountaineering”.

Saoirse departs from Dun Laoghaire in June 1923 at the start of her voyage. Photo Irish Times In fact, so clearcut had Worth been in his analysis that he provided the Introduction for Conor O’Brien’s entertaining if sometimes eccentric account of Saoirse’s circumnavigation, the timeless sailing classic Across Three Oceans. Claud Worth’s foreword has so much insight that it continues today to be the final word on the voyage, and in a few pithy comments he sums up what had been achieved by the 42ft ketch to O’Brien’s own design, and built in fishing boat style by Tom Moynihan and his shipwrights in Baltimore.

Saoirse departs from Dun Laoghaire in June 1923 at the start of her voyage. Photo Irish Times In fact, so clearcut had Worth been in his analysis that he provided the Introduction for Conor O’Brien’s entertaining if sometimes eccentric account of Saoirse’s circumnavigation, the timeless sailing classic Across Three Oceans. Claud Worth’s foreword has so much insight that it continues today to be the final word on the voyage, and in a few pithy comments he sums up what had been achieved by the 42ft ketch to O’Brien’s own design, and built in fishing boat style by Tom Moynihan and his shipwrights in Baltimore.

“Mr O’Brien’s plain seamanlike account is so modestly written that a casual reader might miss its full significance” wrote Worth. “But anyone who knows anything of the sea, following the course of the vessel day by day on the chart, will realize the good seamanship, vigilance and endurance required to drive this little bluff-bowed vessel, with her foul uncoppered bottom, at speeds from 150 to 170 miles per day, as well as handling the weight of wind and sea which must sometimes have been encountered”.

The voyage completed, the energetic and sometimes impatient O’Brien was busy with fulfilling the contract he’d brought home with him to build the Ilen to be the Falkland Islands freight and passenger ketch, and with writing his book. Once the latter had appeared, his celebrity was assured, and he was persuaded to enter Saoirse in the 1927 Fastnet Race.

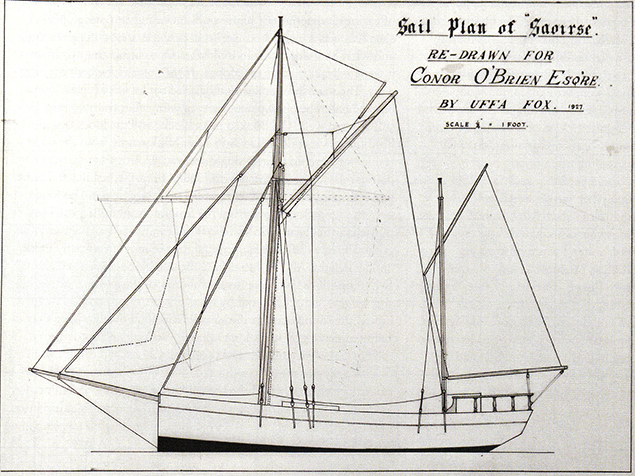

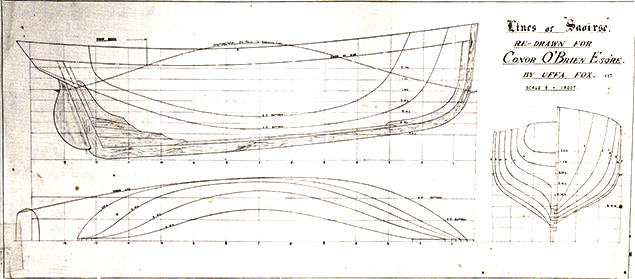

There was much windward work as soon as the fleet had left the Solent, and no-one in the crew disagreed when he eventually withdrew, as he’d re-rigged Saoirse as a sort of mini brigantine, and windward work definitely wasn’t her strong suit. But it had by no means been a wasted expedition, for in Cowes before the race, designer Uffa Fox took off Saoirse’s lines. O’Brien - an architect by training - may have designed her himself, but many of his drawings were distinctly free-form, so now that Saoirse is going to be re-created, the precision of Uffa Fox’s work is going to be invaluable in getting once again the exact shape of “this little bluff-bowed vessel”.

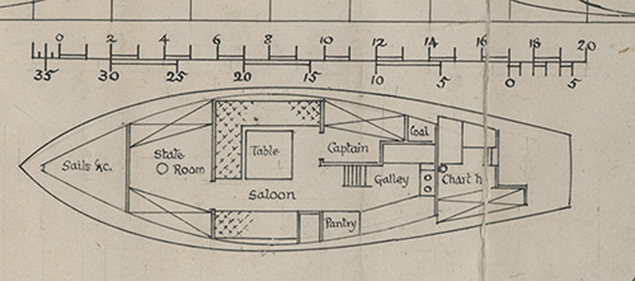

Saoirse’s accommodation - Conor O’Brien’s personal drawings. Courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Saoirse’s accommodation - Conor O’Brien’s personal drawings. Courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

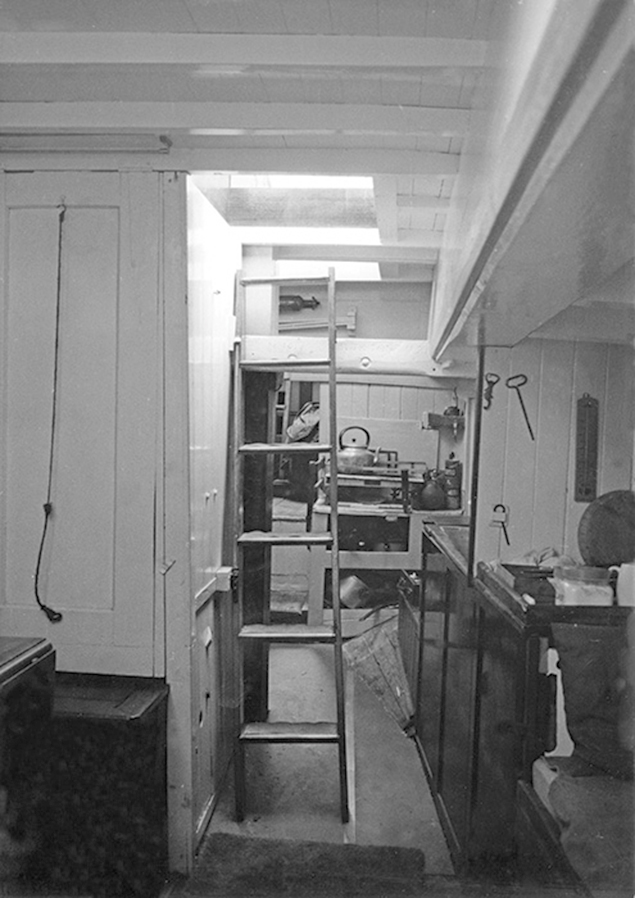

The homely comfort down below. Conor O’Brien may have used old-fashioned concepts in creating Saoirse, but he was well ahead of his time in placing the galley down aft in the position of least motion. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

The homely comfort down below. Conor O’Brien may have used old-fashioned concepts in creating Saoirse, but he was well ahead of his time in placing the galley down aft in the position of least motion. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Saoirse’s hull and sailplan profile as recorded by Uffa Fox in 1927. Courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Saoirse’s hull and sailplan profile as recorded by Uffa Fox in 1927. Courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Saoirse’s hull lines as taken off by Uffa Fox at Cowes in 1927 Courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Saoirse’s hull lines as taken off by Uffa Fox at Cowes in 1927 Courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

As the 1920s drew to a close, Conor O’Brien was at something of a loose end. Of a land-owning family in West Limerick, his expected inherited income had shrunk with the effects of the various Land Acts which had started in the year of his birth, 1880. It was a situation of which a part of him approved, yet he could be such a prickly individual that he never functioned comfortably in the committee situations which his speciality as an ecclesiastical architect required him to work, and thus his earning levels could be precarious

He was uncompromising in his approach to anything and everything. Saoirse was a complete statement of his wish to have a simpler world in which every item was attractively functional. She was the seagoing expression of his enthusiasm for the purest tenets of William Morris’s Arts and Crafts movement. It will be intriguing, when she is reborn, to see if she really is as comfortable as it appears in the drawings and photos. These seem to suggest that she’s the sort of boat it’s a pleasure to be aboard for extended periods, and you will definitely be in her rather than on her - she is a a proper little ship, a world of her own.

Conor O’Brien and Kitty Clausen O’Brien hoisting sail on Saoirse with a chain halyard. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Conor O’Brien and Kitty Clausen O’Brien hoisting sail on Saoirse with a chain halyard. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

It was a world O’Brien needed to share with someone special, and miraculously he found that someone with Kitty Clausen. Of an artistic family, she was nevertheless a practical person who was one of the few people who could make Conor O’Brien content, for in his world voyage his impatience with the short-comings of others meant that, in all, Saoirse carried something like 18 different crewmembers before she finally returned to Dun Laoghaire.

Conor and Kitty were married in 1928, and by 1931 a new and mellower Conor O’Brien had emerged as they sailed a slightly more domesticated Saoirse to the Mediterranean. There, they found the then little-known Balearic Island of Ibiza to be a congenial base where Conor continued writing books, and Kitty provided the illustrations. It was an idyllic existence, and their pleasure in it was reinforced by any return visits they made to the Ireland which was emerging after Independence, for they found it an oppressive place far indeed from the idealism of those who, like Conor O’Brien, had actively supported Home Rule.

The good times. Aboard Saoirse approaching the Spanish coast during the early 1930s, when Conor and Kitty cruised the Mediterranean. In this photo, Saoirse is setting the mini-brigantine rig which O’Brien created using her existing masts in 1927. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

The good times. Aboard Saoirse approaching the Spanish coast during the early 1930s, when Conor and Kitty cruised the Mediterranean. In this photo, Saoirse is setting the mini-brigantine rig which O’Brien created using her existing masts in 1927. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

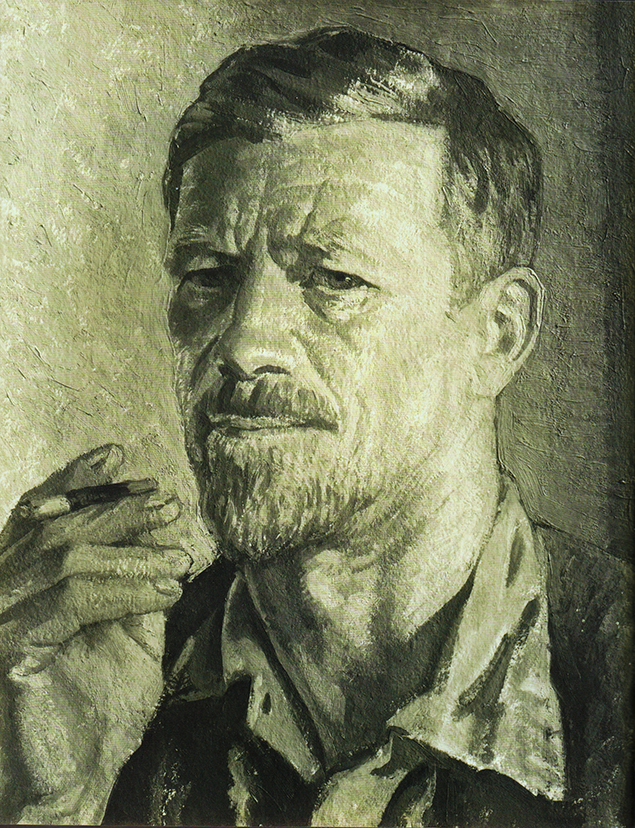

Conor O’Brien as portrayed by Kitty Clausen. Courtesy O’Brien family

Conor O’Brien as portrayed by Kitty Clausen. Courtesy O’Brien family

Thus when they sailed north they tended to go to Falmouth in Cornwall, with their base at St Mawes on the east side of that fine natural harbour. However, cruises to the south continued - they were in the Greek Islands in 1934, and by February 1935 they were wintering in Vigo in northwest Spain. But Kitty’s health was deteriorating, and they returned that summer to St Mawes. She died of leukaemia in 1936, aged 50, and was buried nearby at the waterside church of St Just-in-Roseland.

Conor O’Brien wrote little of her death and what it meant to him, but for some time, his life lost all purpose. He’d lost the urge to cruise Saoirse, and had her hauled in the boatyard across in Falmouth, where he lived a hermit-like existence on board. Then the outbreak of World War II brought him back to life. Like all the gun-runners in 1914, he’d immediately gone into action with the British forces in World War I, serving on mine-sweepers in the North Sea. But on the outbreak of World War II in 1939, with his age now approaching 60 he became involved with the Admiralty Ferry Service, delivering American-built naval and military vessels across the Atlantic.

Aboard Saoirse during the Ruck family’s ownership. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Aboard Saoirse during the Ruck family’s ownership. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Saoirse in Dun Laoghaire during a cruise to Iceland in 1974. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

Saoirse in Dun Laoghaire during a cruise to Iceland in 1974. Photo courtesy O’Brien family/Gary MacMahon

While in America, in 1941 he got an offer which he accepted from Eric Ruck to buy Saoirse in Falmouth. Ruck and his family were happily to continue owning this eccentric but very loveable vessel until the late 1960s, following which she had two owners, one of whom brought her to Ireland in the mid-1970s during a voyage to Iceland, while the other then sailed her across the Atlantic and lost her on a Jamaican beach in heavy weather in 1979.

But for Conor O’Brien, from 1945 onwards after the excitement of World War II, life trickled away. He retreated to a cottage on Foynes Island in the Shannon Estuary, and while he joined family on the island for meals, his was a solitary existence, though visits to “nearby Ireland” could occasionally result in unexpected conviviality.

He died in 1952, aged 72, in a world and in an Ireland very different from the high hopes of the 1920s, when a little ketch had set out from Dublin Bay to celebrate the establishment of a newly independent Ireland. In doing so, she was to make one of the greatest voyages of all time, a pioneering achievement which was publicly recognized at the time.

But by the depressed 1930s, people had other things on their mind, and by the 1950s when Conor O’Brien died, it was largely forgotten outside the circles of dedicated cruising enthusiasts.

Yet time heals, and changes our perspective. The voyage of the Saoirse is now more widely acknowledged than ever as an exceptional seafaring achievement, as is the special genius of Conor O’Brien, and the re-creation of Saoirse is the greatest tribute which can be paid to him.

As for the woman who brought him true happiness for a cruelly short time, it was many years ago that we first visited the sailing enthusiast’s church of St Just-in-Roseland on the east side of Falmouth Harbour. But it was only more recently that we learned that Conor O’Brien’s wife is buried there, under a giant pine tree. Her grave is marked by a simple headstone, designed by her husband in his signature style. It is a peaceful place.

The parish church of St Just-in-Roseland on the eastern shore of Falmouth Harbour. Kitty Clausen O’Brien’s grave is at the foot of the giant pine tree on the right.

The parish church of St Just-in-Roseland on the eastern shore of Falmouth Harbour. Kitty Clausen O’Brien’s grave is at the foot of the giant pine tree on the right.

The simple headstone, designed by Conor O’Brien. Photo: W M Nixon

The simple headstone, designed by Conor O’Brien. Photo: W M Nixon