Displaying items by tag: Water Club

#yachtclubs – The antiquity of Irish recreational sailing is beyond dispute, even if arguments arise as to when it started, and whether or not the Royal Cork YC really is the world's oldest club in its descent from the Water Club of the Harbour of Cork from 1720. But all this seems academic when compared with the impression made by relics of Ireland's ancient sailing traditions.

In just six short years, the Royal Cork Yacht Club will be celebrating its Tercentenary. In Ireland, we could use a lot of worthwhile anniversaries these days, and this 300th has to be one of the best. The club is so firmly and happily embedded in its community, its area, its harbour, in Munster, in Ireland and in the world beyond, that it is simply impossible to imagine sailing life without it.

While the Royal Cork is the oldest, it's quite possible it wasn't the first. That was probably something as prosaic as a sort of berth holder's association among the owners of the ornamental pleasure yachts which flourished during the great days of the Dutch civilisation in the 16th and 17th Centuries. They were based in their own purpose-built little harbours along the myriad waterways in or near the flourishing cities of The Netherlands. Any civilisation which could generate delightful bourgeois vanities like Rembrandt's Night Watch, or extravagant lunacies such as the tulip mania, would have had naval-inspired organised sailing for pleasure and simple showing-off as central elements of its waterborne life.

Just sailing for pleasure and relaxation, rather than going unwillingly and arduously afloat in your line of work, seems to have been enough for most. Thus racing – which is the surest way to get some sort of record kept of pioneering activities – was slow to develop, even if inter-yacht matches were held, particularly once the sport had spread to England with the restoration of Charles II in 1660.

Ireland had not the wealth and style of either Holland or England, but it had lots of water, and it was in the very watery Fermanagh region that our first hints of leisure sailing appeared. It's said of Fermanagh that for six months of the year, the lakes are in Fermanagh, and for the other six, Fermanagh is in the lakes. Whatever, the best way to get around the Erne's complex waterways system, which dominates Fermanagh and neighbouring counties, was by boat. By the 16th Century Hugh Maguire, the chief of the Maguires, aka The Maguire, had a Lough Erne-based fleet, some boats of which were definitely for ceremonial and recreational use.

Sport plays such a central - indeed total - role in Irish life that it's highly likely these pleasure sailing boats were sometimes used for racing. However, the first recorded race anywhere in Ireland took place in Dublin Bay in 1663 when the polymath Sir William Petty, having built his pioneering catamaran Simon & Jude, then organised a race with a Dutch sailing vessel and a local "pleasure boatte" of noted high performance. This event, re-sailed in 1981 when the indefatigable Hal Sisk organised the building of a re-creation of the Simon & Jude, resulted both times in victory for the new catamaran. But because a larger sea-going version of the Simon & Jude, called The Experiment at the suggestion of Charles II himself, was later to founder with all hands while on a testing voyage in the Bay of Biscay, the multi-hull notion was abandoned in Europe for at least another two centuries.

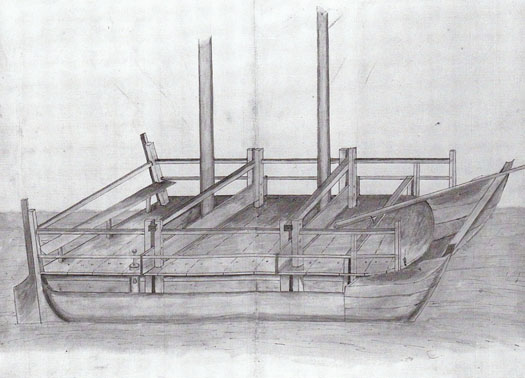

Contemporary drawing of the 17th Century catamaran Simon & Jude, which was built in Dublin and tested in the bay in an early "yacht race" in 1663.

We meanwhile are left wondering just what was this "pleasure boatte" was, and who owned and sailed it. Its existence and good sailing performance seems to have been accepted as unremarkable in Dublin Bay, yet no other record or mention of it has survived.

It was the turbulent life of Munster in the 17th Century which eventually created the conditions in which the first yacht club was finally formed. As the English Civil War spread to Ireland at mid-Century with a mixture of internecine struggle and conquest, the Irish campaigner Murrough O'Brien, the Sixth Baron Inchiquin, changed sides more than once, but made life disagreeable and dangerous for his opponents whatever happened to be the O'Brien side for the day.

Yet when the forces supporting Charles II got back on top in 1660 after the death of Cromwell in 1658, O'Brien was on the winning side. As the dust settled and the blood was washed away, he emerged as the newly-elevated Earl of Inchiquin, his seat at Rostellan Castle on the eastern end of Cork's magnificent natural harbour, and his interests including a taste for yachting acquired with his new VBF Charles II.

But there was much turmoil yet to come with the Williamite wars in Ireland at the end of the 17th Century. Yet somehow as the tide of conflict receded, there seemed to be more pleasure boats about Cork Harbour than anywhere else, and gradually their activities acquired a level of co-ordination. The first Earl of Inchiquin had understandably kept a fairly low profile once he got himself installed in his castle, but his descendants started getting out a bit and savouring the sea. So when the Water Club came into being in 1720, the fourth Earl of Inchiquin was the first Admiral.

In the spirit of the times, having an aristocrat as top man was sound thinking, but this was truly a club with most members described as "commoners", even if there was nothing common about their exceptional wealth and their vast land-holdings in the Cork Harbour area. Much of it was still most easily reached by boat, thus sailing passenger vessels and the new fancy yachts interacted dynamically to improve the performance of both.

Yet there was no racing. Rather, there was highly-organised Admiral Sailing in formation, something which required an advanced level of skill. However, many of the famous club rules still have a resonance today which gives the Water Club a sort of timeless modernity, and bears out the assertion by some historians that, as it all sprang to life so fully formed, the formation date of 1720 must be notional, as all the signs are that there had been a club of some sort for years beforehand.

But either way, it makes no difference to the validity or otherwise of the rival claim, that the Squadron of the Neva at St Petersburg in Russia, instituted by the Czar Peter the Great in 1718 to inculcate an enthusiasm for recreational sailing among Imperial Russia's young aristocrats, was the world's first yacht club. It was no such thing. It was in reality a unit of the Russian navy, and imposed by diktat from the all-powerful ruler. As such, it was entirely lacking the basic elements of a true club, which is a mutual organisation formed by and among equals.

Yet as the Water Club of the Harbour of Cork had no racing with results published in what then passed for the national media, we are reliant on the few existing club records and some travel writing from the time for much of our knowledge of the early days of the Water Club. That, and the Peter Monamy paintings of the Water Club fleet at sea in 1738.

A remarkably well-disciplined fleet. Peter Monamy's 1738 painting of the yachts of the Water Club at sea off Cork Harbour. They weren't racing, but were keeping station in carefully-controlled "Admiral Sailing". Courtesy RCYC

Fortunate indeed are the sailors of Cork, that their predecessors' activities should have been so superbly recorded in these masterpieces of maritime art. The boats may look old-fashioned to a casual observer, yet there's something modern or perhaps timeless in this depiction of the fleet sailing in skilled close formation, and pointing remarkably high for gaff rigged boats as they turn to windward. Only a genuine shared enthusiasm for sailing could have resulted in such fleet precision, and in its turn in a memorable work of art. It is so much part of Irish sailing heritage that we might take it for granted, but it merits detailed study and admiration no matter how many times you've seen it already.

Shortly after Monamy's two paintings were completed, Ireland entered a period of freakish weather between 1739 and 1741 when the sun never shone, yet it seldom if ever rained, and it was exceptionally cold both winter and summer. It is estimated that, proportionately speaking, more people died in this little known famine than in the Great Famine itself 104 years later. While the members of the Water Club would have been personally insulated from the worst of it, the economic recession which struck an intensely agricultural area like Cork affected all levels of society.

Thus the old Water Club saw a reduction in activity, but though it revived by the late 1740s, the sheer energy and personal commitment of its early days was difficult to recapture, and by the 1760s it was becoming a shadow of its former self. Nevertheless there was a revival in 1765 and another artist, Nathanael Grogan, produced a noted painting of Tivoli across from Blackrock in the upper harbour, with a yacht of the Water Club getting under way for a day's recreation afloat, the imminent departure being signalled by the firing of a gun.

The best way to get the crew on board....on upper Cork Harbour at Tivoli in 1765, a yacht of the reviving Water Club fires a gun to signal imminent departure.

However, it was on Ireland's inland waterways that the next club appeared – Lough Ree Yacht Club came into being in 1770, and is still going strong. That same year, one of the earliest yacht clubs in England appeared at Starcross in Devon, but it was in London that the development pace was being most actively set with racing in the Thames for the Cumberland Fleet. Some members of this group, after the usual arguments and splits which plague any innovative organisation, in due course re-formed themselves as the Royal Thames Yacht Club in the early 1800s. But the famous yet unattributed painting of the Cumberland Fleet racing on the Thames in 1782, while it is slightly reminiscent of Monamy's painting of the Water Club 44 years earlier, undoubtedly shows boats racing. And they'd rules too – note the port tack boat on the right of the picture bearing off to give way to the boat on starboard.

Definitely racing – the Cumberland Fleet, precursor of the Royal Thames Yacht Club, racing in the River Thames at Blackfriars in 1782.

The Thames was wider in those days, but even so they needed strict rules to make racing possible. Dublin Bay offered more immediate access to open water, and there were certainly sailing pleasure boats about. When the Viceroy officially opened the Grand Canal Dock on April 23rd 1796, it was reported that the Viceregal yacht Dorset was accompanied by a fleet of about twenty ceremonial barges and yachts. Tantalisingly, the official painting is almost entirely focused on the Dorset and her tender, while the craft in the background seem to be naval vessels or revenue cutters.

This painting of the opening of the Grand Canal Dock in 1796 tends to concentrate on the ceremonials around the Viceroy's yacht Dorset in the foreground, but fails to show clearly any of the several privately-owned yachts which were reportedly also present....

.......but this illustration of the old Marine School on the South Quays in Dublin in 1803 seems to have a yacht – complete with owner and his pet dog on the dinghy in the foreground – anchored at mid-river.

However, a Malton print of the Liffey in 1803 shows clearly what is surely a yacht, the light-hearted atmosphere of waterborne recreation being emphasised by the alert little terrier on the stern of the tender conveying its owner in the foreground Meanwhile in the north of Ireland there was plenty of sailing space in Belfast Lough, while Belfast was a centre of all sorts of innovation and advanced thinking. Henry Joy McCracken, executed for his role in the United Irishmen's rising in 1798, was a keen pioneer yachtsman. As things took a new turn of determined money-making in Belfast after the Act of Union of 1801, some of his former crewmates were among those who formed the Northern Yacht Club in 1824, though it later transferred its activities across the North Channel to the Firth of Clyde, and still exists as the Royal Northern & Clyde YC.

Meanwhile in 1806 the old Water Club of the Harbour of Cork had shown new signs of life, but one result of this was an eventual agreement among members - some of them very old indeed, some representing new blood - that the club would have to be re-structured and possibly even given a new name in order to reflect fresh developments in the sport of yachting. The changeover was a slow business, as it had to honour the club's history while giving the organisation contemporary relevance. Thus it was 1828 before the Royal Cork Yacht Club had emerged in this fully fledged new form, universally acknowledged as the continuation of the Water Club, and incorporating much of its style.

But it was across the north on Lough Erne in 1820 that the world's first yacht club specifically set up to organise racing was formed, and Lough Erne YC continues to prosper today, its alumnae since 1820 including early Olympic sailing medallists and other international champions.

There must have been something in the air in this northwest corner of Ireland in the 1820s, for in 1822 the men who sailed and raced boats on Lough Gill at Sligo had a pleasant surprise. Their womenfolk got together and raised a subscription for a handsome silver trophy to be known as the Ladies' Cup, to be raced for annually – and it still is.

Instituted in 1822, the Ladies' Cup of Sligo YC is the world's oldest continually-contested annual sailing trophy.

Annual challenge cups now seem such a natural and central part of the sailing programme everywhere that it seems extraordinary that a group of enthusiastic wives, sisters, mothers and girlfriend in northwest Ireland were the first to think of it, yet such is the case. Or at least theirs is the one that has survived for 192 years, so its Bicentenary in 2022 is going to be something very special.

Those racing pioneers of the Cumberland Fleet had made do with new trophies freshly presented each year. And apparently the same was the case initially at Lough Erne. But not so very far down the road, at Sligo, somebody had this bright idea which today means that the museum in Sligo houses the world's oldest continually raced-for sailing trophy, and once a year it is taken down the road to the Sligo YC clubhouse at Rosses Point to be awarded to the latest winner – in 2013, it was the ever-enthusiastic Martin Reilly with his Half Tonner Harmony.

The Ladies Cup was won in 2013 by Martin Reilly's Half Tonner Harmony. Pictured with their extremely historic trophy are (left to right) Callum McLoughlin, Mark Armstrong, Martin Reilly, John Chambers, Elaine Farrell, Brian Raftery and Gilbert Henry

However, although the Ladies' Cup may have pioneered a worthwhile trend in yacht racing, it wasn't until 1831 that they thought of inscribing the name of the winner, and that honour goes to Owen Wynne of Hazelwood on the shores of Lough Gill. But by that time the notion of inscribing the winners was general for all trophies, and a noted piece of the collection in the Royal Cork is the Cork Harbour Regatta Cup 1829, and on it is inscribed the once-only winner, Caulfield Beamish's cutter Little Paddy.

The name of noted owner, skipper and amateur yacht designer Caulfield Beamish came up here some time back, when we were discussing how in 1831 he took a larger new yacht to his own design, the Paddy from Cork, to Belfast Lough where he won a stormy regatta. So you begin to understand the mysterious enthusiasm people have for sacred relics when you see this cup with its inscription, and realise that it's beyond all doubt that this now-forgotten yet brilliant pioneer of Cork Harbour sailing development personally held this piece of silverware.

Caulfield Beamish's new cutter Paddy from Cork (which he designed himself) winning a stormy regatta in Belfast Lough in 1831

The Cork Harbour Regatta Cup of 1829.....Courtesy RCYC

....and on it is inscribed the winner, Caulfield Beamish's earlier boat, Little Paddy, which he also designed himself. Courtesy RCYC

Another pioneer in yacht racing at the time was the Knight of Glin from the Shannon Estuary, who in 1834 was winning all about him with his cutter Rienvelle, his season's haul including a silver plate from a regatta in Galway Bay – it's now in Glin Castle – while he also seems to have relieved fellow Limerick owner William Piercy of £50 for a match race in Cork Harbour against the latter's cutter Paul Pry.

The lads from Limerick hit Cork. William Piercy's Paul Pry racing for a wager of £50 against the Knight of Glin's Rienvelle in Cork Harbour in 1834. When Paul Pry won Cork Harbour Regatta a few weeks later, the band on the Cobh waterfront played Garryowen. Courtesy RCYC

But of all the fabulous trophies in the Royal Cork collection, the one which surely engenders the most affection is the Kinsale Kettle. It goes back "only" to 1859, when it was originally the trophy put up for Kinsale Harbour Regatta. But this extraordinarily ornate piece of silverware was not only the trophy for an annual race, it was also the record of each race, as it's inscribed with brief accounts of the outcomes of those distant contests.

An extraordinary piece of Victorian silverware. The "Kinsale Kettle" from 1859 is now the Royal Cork YC's premier trophy.

Today, it continues to thrive as the Royal Cork Cup, the premier award for Cork Week. The most recent winner in 2012 was Piet Vroon with his superb and always enthusiastic Tonnere de Breskens. The fact that this splendid ambassador for Dutch sailing should be playing such a central role in current events afloat here in Ireland brings the story of our sport's artworks and historical artefacts to a very satisfactory and complete circle.

More tea, skipper? The current holder of the Kinsale Kettle, aka the Royal Cork Cup, is Piet Vroon of Tonnere de Breskens. Photo: Bob Bateman