Displaying items by tag: ICC

Thinking of chartering a boat abroad? Thinking of refreshing your navigation and chart work skills? Do you remember what lights vessels towing at night should show? Are you looking for something to do on wintery Monday nights?

There are many reasons why you should consider enrolling in an Enhanced International Certificate of Competency Course with the National Yacht Club in 2019/2020.

Theory courses for the International Certificate of Competency (ICC) will be held in the NYC during the coming winter months.

Each theory course will consist of five Monday evenings of tuition and one evening written test, with classes running for two-and-a-half hours from 7.15pm.

Course one begins on Monday 4 November and continues to Monday 9 December. Course two begins Monday 13 January and runs until Monday 17 February.

A minimum of four students are required for course to go ahead, with a maximum of 12 students per course to insure quality of tuition.

Sir Dennis Faulkner 1926-2016

One of the most noted sailing figures in Northern Ireland, Sir Dennis Faulkner died peacefully at his home close along the shore beside the hidden waters of Ringhaddy Sound in Strangford Lough at the age of 90 on New Year’s Eve.

Although in the public eye he may have been best known as the younger brother of Brian Faulkner, who was five years his senior and was Prime Minister of Northern Ireland in the early 1970s, while Dennis cherished his privacy he was active in voluntary naval and military service. This was in addition to being a leading businessman associated with several major companies, and he was also a very keen sailing enthusiast from childhood.

His boyhood was spent on the shores of Ballyholme Bay on Belfast Lough, and at an early age he showed his capacity to combine the skills of a seaman with the acumen of a considerable business talent. Spotting a dinghy drifting out of the bay in a strong offshore wind with the crew unable to cope with the conditions, he quickly effected a rescue. Yet by the time he was being praised by the local newspaper as “the schoolboy hero”, he personally was busy with pursuing an insurance claim for the salvage of the boat.

This combination of sailing ability with a businesslike approach to life was inherited from his father Jimmy Faulkner, who built up a commercial empire in Northern Ireland based initially on shirt manufacture, successfully maintaining contacts throughout Ireland and abroad both for business and sport. Thus when the first list of Irish Cruising Club members was compiled in 1930 after the club’s foundation in the summer of 1929, Jimmy Faulkner was on that inaugural list as owner of the 12-ton cutter Bryden.

Dennis Faulkner’s spiritual home, where he built his dream house and off it moored a succession of fine yachts

Dennis Faulkner’s spiritual home, where he built his dream house and off it moored a succession of fine yachts

Later, in the summer of 1930, he went to his favourite cruising area, the West Coast of Scotland, in company with the new ICC’s first Commodore, Herbert Wright of Dun Laoghaire with his 15-ton cutter Espanola. Soon afterwards, Jimmy Faulkner presented the Irish Cruising Club with its first trophy, the Faulkner Cup. This led to the annual log competition which was instituted in 1931, and today it is the senior Irish cruising award, still competed for annually by boats and crews who have been to every corner of the world.

Initially, while young Dennis crewed from time to time with his father, racing was his primary interest, and he was seldom without a boat in one of the north’s leading One-Design classes. Much of his sailing focus had moved to Strangford Lough where he was involved with the River and Glen classes at Whiterock, but as he continued to live near the shores of Belfast Lough he also played an active role in the introduction of the Squib Class at Royal North of Ireland YC at Cultra.

However, when time permitted he participated in major international RORC events through a friendship with Geoffrey Pattinson who was best known for ownership of the successful Robert Clark-designed 55ft alloy sloop Jocasta , built 1950. With boats like this, Dennis Faulkner not only logged many ruggedly-raced offshore miles including several Fastnets, but he also built up a network of useful acquaintances who appreciated his toughness in hard-driving ocean conditions. As a result, he must have been one of the few people in all Ireland who had taken part in what used to be a southern hemisphere classic, the Buenos Aires-Rio de Janeiro Race.

In home waters, he also registered a win in a southwest gale as sailing master aboard a friend’s boat in the RUYC’s annual Ailsa Craig Race, but although he owned a succession of fine cruiser-racers, he was too fond of them to drive them to the uttermost in heavy weather. And having succeeded his father into membership of the Irish Cruising Club in 1960, the Hebrides continued to be the Faulkner family’s favourite cruising ground, where in time his liking for the Outer Hebrides was such that he bought a remote cottage on the shores of Loch Mariveg on the east coast of Lewis south of Stornoway. Any cruising enthusiasts who happened to find their way to this extremely secret spot found a very relaxed and hospitable Dennis Faulkner who had for the time being shed the cares of life back in Northern Ireland.

Inevitably his administrative talents were such that he joined the Irish Cruising Club Committee, and in 1969 he became Commodore ICC. At this stage his pet boat was the 49ft Robert Clark-designed Zest of Strangford, a hull-sister of Denis Doyle’s first Moonduster. The new Commodore ICC sailed Zest to Crosshaven to join the 1969 Cruise-in-Company of the leading cruising clubs – including a large Transatlantic contingent from the Cruising Club of America – as the opening salvo of the two year celebration of the Quarter Millennium of the Royal Cork Yacht Club.

The Cruise-in-Company fleet in the Parade of Vessels in Cork Harbour which started the Royal Cork Yacht Club’s Quadrimillennial celebrations in 1969. Photo courtesy ICC

The Cruise-in-Company fleet in the Parade of Vessels in Cork Harbour which started the Royal Cork Yacht Club’s Quadrimillennial celebrations in 1969. Photo courtesy ICC

While voyaging to Cork, Zest had taken in tow a motor-boat with a broken-down engine. Whether or not this strained her own engine installation can only be guessed at, but during the Quadrimillennial Parade of Vessels under power round Cork Harbour – reviewed by An Taoiseach Jack Lynch – it was arranged that Zest would tow the engine-less Moonduster, and a problem occurred.

All was going well, the sun shone, the colours fluttered in the breeze, but then Zest’s propeller shaft fractured under the added load. However, Richard Nye’s famous 48ft Carina – then brand new and fresh in from racing Transatlantic – was next in line, and she took the two immobilised Irish boats in tow in such a smooth exercise that, as the two Dennises subsequently remarked, anyone watching assumed it was a pre-arranged and carefully-rehearsed part of the Parade.

That astonishing large-scale Cruise-in-Company – the first such in Irish waters - culminated in Glengarriff with a massive party at exactly the time the first American astronauts walked on the moon. It now all seems a very distant time ago, and in the long interval since, Dennis Faulkner never lost his love of sailing, while his fondness for Strangford Lough was eventually fulfilled by being able to build his dream home, a gently-styled house which blends well with its peaceful surroundings, on the shore of his beloved Ringhaddy Sound.

There, the Faulkner family showed what could be done in harmony with the environment, and his daughter and son-in-law have emerged among County Down’s leading horticulturalists. Dennis meanwhile continued his discerning pattern of cruising yacht ownership, his final serious voyaging craft being an Amel Super Maramu 54 ketch, a long way indeed from his father’s old clinker-built Scottish-style double-ender Bryden.

The 1969 Cruise-in-Company in Castlehaven – the schooner is Integrity (CCA). The cruise concluded in Glengarriff at the end of July when the American astronauts first walked on the moon. Photo courtesy ICC

The 1969 Cruise-in-Company in Castlehaven – the schooner is Integrity (CCA). The cruise concluded in Glengarriff at the end of July when the American astronauts first walked on the moon. Photo courtesy ICC

The family involvement with the cruising community worldwide - and particularly in Ireland - continued, and it was way back in 1970 that Dennis Faulkner found himself faced with the task of adjudicating the ICC logs, a process which had been started by his father’s presentation of the Faulkner Cup in 1931.

In honour of this, and in acknowledgement of the growth of the club and its activities since, he inaugurated a new trophy, the Strangford Cup for “an alternative best cruise”, which he duly awarded for 1970 to Rory O’Hanlon of Dun Laoghaire for his cruise to the Lofoten Islands in northern Norway with his S&S sloop Clarion.

Dennis Faulkner’s greatest enjoyment lay in interacting with the sea, in its most open form when he was in his prime, and in the intimate waters of Strangford Lough as the years moved on. He never lost his adventurous spirit, and on sailing through Ringhaddy Sound one day, we were much impressed by seeing the man himself out for a quick spin on a windsurfer. His final boat was Whimbrel, a Hawk day-sailer, and with her he rounded out a very complete life afloat. Our thoughts are with his family and many friends in their sad loss.

WMN

Joe Fitzgerald 1922–2016

Joe Fitzgerald of Cork went from among us a month and more ago at the age of 94. That month provides us with an added perspective for a full appreciation of his well-lived life afloat and ashore. It enhances our understanding of just how completely land and sea can become happily intertwined in life around Cork Harbour and city.

When that way of life is being lived by someone with Joe’s quiet yet always enthusiastic appreciation of the opportunities for good times in the world of boats and sailing, we find we’re looking at a long life which was a gentle inspiration and encouragement to all who knew him.

He seemed to find the perfect balance between running a demanding yet fulfilling business in the fashionable heart of Cork city, and relaxing through sailing and the company of sailing folk. The family firm in which he succeeded his father was the iconic Fitzgerald menswear, a tailoring and clothing company and shop which Joe elevated to such a reputation for quality in all areas that it’s said the young Louis Copeland, that legend of men’s tailoring, readily travelled from Dublin in order to enhance his skills by working with Joe Fitzgerald, learning from his notable eye for fabric and finish.

All these skills were allied to an astute yet very proper business aptitude. Nevertheless a good week’s work would be celebrated at its conclusion in proper style with a host of such quiet charm that when you found yourself relaxing after business hours in Joe’s company in the heart of Cork city, the sense of being in the midst of true civilisation was central to the mood of the evening, and that mood of generous enjoyment would then be carried on to the weekend’s projects in and around boats and sailing.

Despite his small stature - it’s thought that it was his longtime friend Stanley Roche who first called him “The Tiny Tailor”, though others in Cork will claim it was a northern friend – Joe was a tower of strength around boats, and he first acquired his sailing skills through spending his boyhood summers with an uncle who had a Brixham trawler converted to a sailing cruiser, and based in Crosshaven.

Although during his working years his family home was in Blackrock, Crosshaven remained his sailing home for the rest of his long life, and for his final decade he was a resident of the apartments which had been developed in the former Grand Hotel just across the road from the side door to the Royal Cork Yacht Club, where he was wont to meet his special circle of friends.

This link to shore living in Crosshaven went back to the late 1930s when Joe and some young contemporaries rented a house in the village on a year-round basis. They became much involved with the local dinghy sailing scene through the Cork Harbour Sailing Club, where the inspiration was top international helm Jimmy Payne, who saw to it that the club had a fleet of International 12 sailing dinghies available for charter at 10 shillings for half a day at a time when The Emergency engendered by World War II might have made access to sailing difficult

The International 12s racing at Crosshaven in the 1940s. Photo courtesy RCYC

The International 12s racing at Crosshaven in the 1940s. Photo courtesy RCYC

Soon, a core of useful dinghy sailing experience built up. But by 1943 the waters around neutral Ireland were less directly affected by the war, and the Irish Cruising Club organised a race from Crosshaven around the Fastnet. Lest this seem callous at a time when war was still being waged, it should be noted that several naval and military officers on active service with the Allied forces managed to arrange leave in order to participate.

Among the boats taking part was the famous Gull from Crosshaven, one of the seven participants in the first international Fastnet Race of 1925. Although her legendary skipper Harry Donegan had died in 1940, his son Harry Jnr continued the family ownership of Gull, and for that race of 1943, he included the young Joe Fitzgerald in the crew. As a result, Joe Fitzgerald was elected a member of the Irish Cruising Club in 1944 on the proposal of Harry Donegan Jnr, and today the Fitzgerald ICC membership of 72 years has the air of the eternal record to it.

The Donegan family’s Gull, a veteran of the first international Fastnet Race of 1925, aboard whch Joe Fitzerald qualified for Irish Cruising Club membership in 1944. Photo: Courtesy RCYC

The Donegan family’s Gull, a veteran of the first international Fastnet Race of 1925, aboard whch Joe Fitzerald qualified for Irish Cruising Club membership in 1944. Photo: Courtesy RCYC

Joe Fitzgerald was also busy in 1944 in other ways afloat, as he was continuing to play a key role in the dinghy sailing of the Cork Harbour Sailing Club, and 1944 saw the first races by CHSC in International 12s against Sutton Dinghy Club for “The Book”, the monumental volume in which each year’s racing is recorded by the winning team. It continues today with Sutton DC still in the picture, but it’s the mighty Royal Cork Yacht Club itself which now represents Cork Harbour, and has done so since 1970. Nevertheless it was a surprise for participants in 1988’s event in Crosshaven when Joe Fitzgerald was asked to speak at the dinner, and he gave his typically dry-humoured account of the racing in 1944 all of 44 years previously and waxed enthusiastic about the goodwill which The Book has generated ever since.

The teams racing for “The Book” at Sutton Dinghy Club in 1944. Joe Fitzgerald, on the Cork Harbour SC team, is third from the right of those seated at front. Photo courtesy SDC/RCYC

The teams racing for “The Book” at Sutton Dinghy Club in 1944. Joe Fitzgerald, on the Cork Harbour SC team, is third from the right of those seated at front. Photo courtesy SDC/RCYC

In addition to sailing for sport, Joe Fitzgerald in the 1940s joined the Maritime Inscription, continuing with the voluntary naval reserve which was re-formed as An Slua Muiri after the war. He recalled that his commissioning papers were signed by Eamonn de Valera himself, and his career with the force went on for 39 years. It’s said that he was within weeks of serving for forty years, but the stipulated retirement age was upon him. His many friends and colleagues hoped that the bureaucrats might stretch the rules just a tiny bit to allow him see out the forty years, but the bureaucracy was not for budging. Nevertheless Joe could retire from his many years of service knowing that he had been the youngest Commanding Officer of any region in Ireland.

Meanwhile he had long since been involved in sailing administration, having become Honorary Secretary of Cork Harbour Sailing Club in 1946 while also being an active member of the Royal Munster YC in Crosshaven. There was change in the air, and very suddenly in the late 1940s the International 12s, the backbone of Irish dinghy sailing for many years, found themselves being rapidly displaced by new boats such as the Fireflies and IDRA 14s in Dublin Bay, and the IDRA 14s and National 18s in Cork Harbour.

Joe opted for a George Bushe-built IDRA 14, and soon showed his mettle by winning the IDRA 14 Nationals at Dunmore East in 1951 in his new Mystery, crewed by Michael Donnelly. He was also crewing increasingly on larger craft, both for offshore racing and cruising. But when his father died suddenly at the age of 49 of a heart attack he had to re-direct energies into the family business.

It was a salutary lesson for him, as thereafter, while he was undoubtedly enjoying the good life with a high level of conviviality with a special coterie of close friends, he was way ahead of his time in keeping himself fit. His health regime - which he continued to the end of his days - included a cycling machine in a spare room in the house, and a programme of exercises which saw regular press-ups until well into his nineties.

Yet with a family on the way with his wife Maddie, he seemed the ordinary unfussed successful Cork businessman with a taste for sport and particularly sailing. In the 1960s, in addition to sailing on larger boats with top skippers such as Denis Doyle and Tom Crosbie, he got involved with the lively International Dragon Class which was growing at Crosshaven.

Almost all the boats in it were classic Scandinavian-built Dragons, but Joe decided he’d have his one built at Denis Doyle’s Crosshaven boatyard by the hugely-skilled George Bushe, who had already built his winning IDRA 14 Mystery.

George Bushe made a very good job of building the new Dragon class Melisande. In fact, he made too good a job of it. When the official measurer arrived over in Ireland to approve Melisande, he pointed out that as the Dragon was conceived as a basic economical boat, the frames were meant to have a simple rectangular section. Yet George in his love of providing a good finish had rounded off the exposed edges of the frames. The measurer was not for turning. Melisande would not be recognised as a true Dragon until the fancy rounded frames were replaced by crude hard-sectioned timbers. It was done. But it took a long time to obliterate the memory of having to do so.

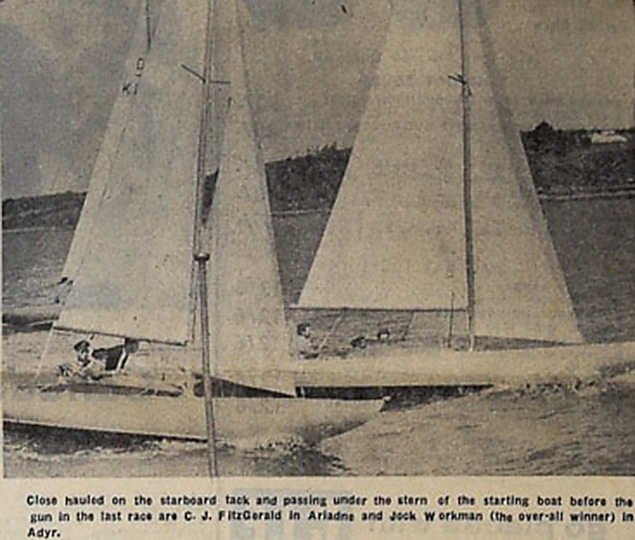

Yet Joe’s time was successful in the Dragons, and he well-represented the Cork fleet in a major international event hosted at Crosshaven in 1962, coming third against the likes of winner Jock Workman from Belfast Lough and runner-up J L F Crean from the Solent.

A photo from the Cork Evening Echo in 1962. The International Dragon Series at Crosshaven, with Joe Fitzgerald sailing for Cork Harbour (foreground) getting the better of eventual overall winner Jock Workman of Belfast Lough at the start

A photo from the Cork Evening Echo in 1962. The International Dragon Series at Crosshaven, with Joe Fitzgerald sailing for Cork Harbour (foreground) getting the better of eventual overall winner Jock Workman of Belfast Lough at the start

At the 1962 Dragon Open Series are skipper Joe Fitzgerald (left) with his crew of P J Kavanagh and Mick Sullivan

At the 1962 Dragon Open Series are skipper Joe Fitzgerald (left) with his crew of P J Kavanagh and Mick Sullivan

But increasingly he found most pleasure in cruiser-racers, and he teamed up with longtime friend Peter Cagney to order a new Cuthbertson & Cassian-designed Trapper 28, finished on a bare glassfibre hull by George Bushe at his new yard at Rochestown. It was now that Joe Fitzgerald really began to spread his wings, and every possible free moment was used for cruising, though their explorations were not without the occasional mishap.

Approaching Courtmacsherry long before it was a popular port of call, Peter was below and Joe was at the helm when they lightly clipped a rock. In response to the roar from below, the helmsman blithely replied: “Your half of the boat has just struck a rock, but it’s nothing serious……”

Building on experience over the years with his own boats and the larger vessels of friends, Joe Fitzgerald developed an entire philosophy of cruising in which he built up a complete matrix of friendly ports mostly on the Cork coast but also further afield and internationally too, and as well he showed how a place like Cork Harbour meant you could have a cruising weekend of some sort virtually regardless of what the weather might throw at you. And of course, if good conditions arrived, it was amazing what he could achieve by adding a day or two on to the beginning or the end of a favourable weekend.

To do this he maintained understanding friendships which provided lifelong bonds, and if other Cork sailors took to calling them “Dad’s Army”, Joe and his friends in turn showed a level of continuing love of boats and sailing which were inspirational to all. With such an approach, it was only natural that Joe Fitzgerald should be called upon to fill important roles in sailing administration, and while he could have his own way of doing things which was not always the way of other people, the very fact of his many sailing and cruising achievements often gave him carte blanche to continue the Fitzgerald administrative style, while his speeches at formal gatherings were gems to be treasured.

Thus having started at Honorary Secretary of Cork Harbour Sailing Club in 1946, he rose through many ranks, becoming Rear Commodore of the Royal Munster YC as long ago as 1949, and then when the Royal Munster and the Royal Cork merged during the late 1960s, the Royal Cork Quadrimillenial Celebrations of 1970 saw Joe in the key role of the still-extant position of Commodore which gave due recognition to the Royal Munster’s input, and then in 1975 he was RCYC Vice Admiral in support of George Kenefick as Admiral.

But it was in the Irish Cruising Club that the light-touch Fitzgerald management style proved most congenial. For many years he was on the Committee, by 1982 he was Vice Commodore, and he was then elected Commodore by acclamation from 1984 to 1986, heading the club with his calming presence at a time of rapid development.

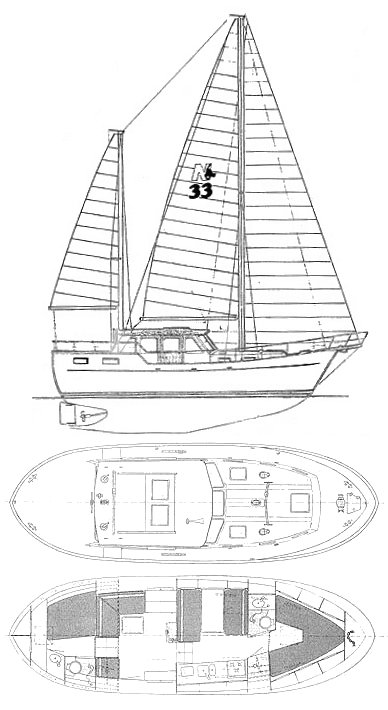

Meanwhile his boat sizes had gently increased, and they reflected the reality of the needs of a sailor who continued in and around his boats afloat on a virtually year round basis. He moved up to a Moody 33 from the Trapper 28, and he was with that Moody 33 when we happened to drop into Youghal of a Saturday night in 1986 on our way to Cork Week in a 30-footer, and there was the Commodore ICC in fine form for a bit of a party, which duly took place.

By 1990 he’d moved on to a Moody Eclipse with its useful deckhouse, and we found ourselves in our little boat in Crosshaven waiting out a Sunday of filthy weather before better weather settled in to carry us south to Biscay. So Joe suggested that as he’d the deckhouse, we should go and spend the day with him on his boat over in East Ferry, and thus the bad weather was let go through without any interruption to the merriment, and next day we went on our way with a fair wind and sunshine, sustained by the entertaining memories of our thoughtful and imaginative clubmate back in Cork.

That’s the way it was with Joe Fitzgerald. He made the best of the hand that life dealt him. A widower since 1983, he still had 33 years to live, and he lived them with quiet enjoyment. He even decided he’d outgrown the Moody Eclipse, and bought himself a hefty Nauticat 33 which took on the Fitzgerald name of Mandalay, and provided an “all indoors” boat which enabled this most gallant senior sailor to continue his love affair with boats and the sea and boat people.

The “All Indoors” boat. The Nauticat 33 enabled Joe Fitzgerald to continue cruising until he’d become a very senior sailor.It is impossible to do full justice to Joe Fitzgerald in ordinary words. The world has been a much more interesting place for his having been in it. His view of life was unique. And his view of death was unusual. For his funeral service, he requested no more than a simple humanist ceremony. Yet we’re told one of the speakers with fond memories was a good old friend who was a former chaplain to the Naval Service at Haulbowline. In his quiet way, Joe Fitzgerald was beyond mere imagination, and he leaves family and friends with many cherished memories.

The “All Indoors” boat. The Nauticat 33 enabled Joe Fitzgerald to continue cruising until he’d become a very senior sailor.It is impossible to do full justice to Joe Fitzgerald in ordinary words. The world has been a much more interesting place for his having been in it. His view of life was unique. And his view of death was unusual. For his funeral service, he requested no more than a simple humanist ceremony. Yet we’re told one of the speakers with fond memories was a good old friend who was a former chaplain to the Naval Service at Haulbowline. In his quiet way, Joe Fitzgerald was beyond mere imagination, and he leaves family and friends with many cherished memories.

WMN

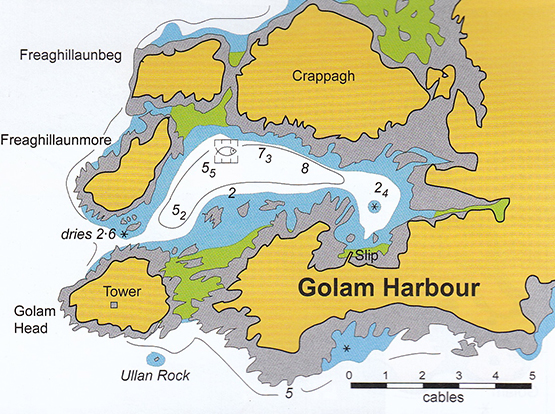

The ultimate dreamworks for those who cruise the Irish coast, or indeed those who just hope to do so one day, has been reaching distributors and subscribers this week with the 14th Edition of the Irish Cruising Club’s Sailing Directions for the South & West Coasts of Ireland coming hot off the press writes W M Nixon.

It’s only three years since the 13th Edition was published, but as Ireland emerges from recession, new harbour developments are taking place. And as well, Honorary Editor Norman Kean, ably assisted by his wife Geraldine Hennigan, is constantly up-dating information, and receiving input from ICC members and other interested folk in all sorts of out of the way places, adding to the already enormous shared stock of top class local knowledge about harbours and anchorages large and small.

The book is available to purchase directly from distributors Todd Navigation via the Afloat marketplace here.

In this age of electronic navigation, it may surprise some that there is a continuing demand for new editions of a book which was first compiled by the great Harry Donegan of Cork in 1930, and he in turn had been collating information, and making harbour charts aimed at the needs of cruising enthusiasts, since 1912.

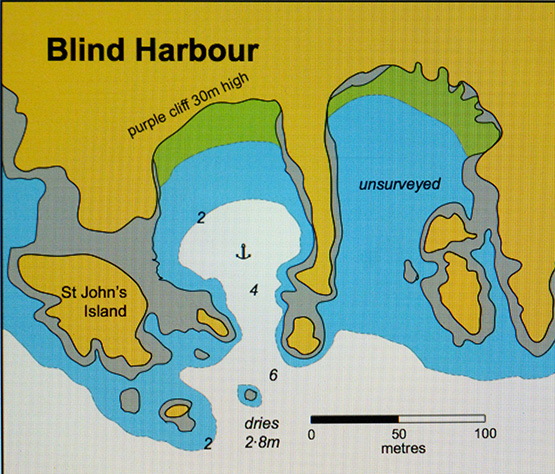

With clear chartlets like this, the ICC makes secret anchorages such as Golam Harbour on the south coast of Connemara accessible to cruising folk from other areas. Courtesy ICC

But in fact this history going back more than a hundred years is part of the book’s attraction. And despite today’s gadgetry, no serious cruising person would contemplate heading off for a detailed venture along the Irish coast without a copy of it on board.

The mixture of technical information well leavened with clear charts and evocative photographs has improved steadily over the years, and the Foreword from Roger Millard, the recently-retired Regional Geographic Manager at the Admiralty Hydrographic Office, neatly encapsulates the high regard in which the ICC Directions are held, as he comments: “Although aimed at small-craft users, it has many admirers from major maritime institutions”.

His Foreword’s conclusion provides a warmth of support beyond professional admiration. Having listed the Directions’ special features of invaluable assistance to small craft users, he concludes: “On top of these advantages, I find it a fascinating read, and I am sure you will enjoy it”.

Goleen in far West Cork is known as a port of call to very few, even though the holiday traffic to Barleycove and Crookhaven barrels through the village every day. Courtesy ICC

While those of us who have cruised the coastlines involved many times will find pleasure in visiting old haunts as they now appear, one of two places where the new book has seen detailed fresh research have been that strange unknown area between Achill Island and Belmullet, a large yet secret location where the noted smuggler Captain James Mathew from Rush in Fingal used to anchor his ship in the 1830s, and small craft would emerge from every nook and cranny nearby. Those aboard each currach would be carrying dockets bought from Mathew’s agents ashore which, once they reached the ship, they could exchange for punitively taxed goods without any money actually changing hands. It was all extremely businesslike, yet the legendary Captain Mathews was chased to his destruction by the Revenue cutters off Donegal in an October storm.

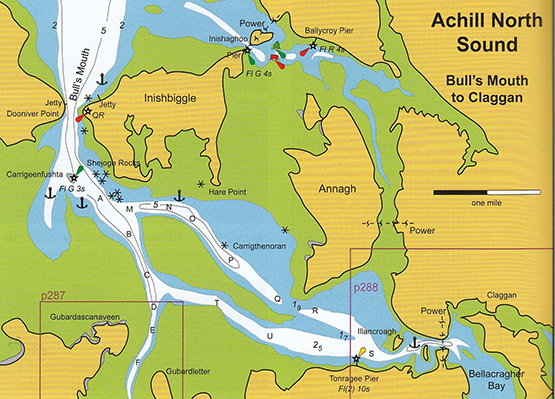

The northern area of Achill Sound is one of the areas re-surveyed for the new Sailing Directions, and some previously unlisted anchorages have been detailed. Courtesy ICC

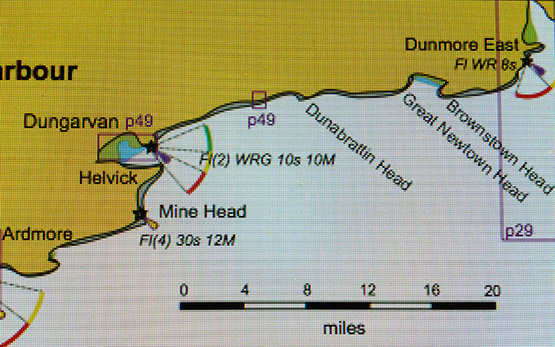

The other area getting the special Keane-Hennigan update is the south coast, eastward of Cork. Regular Afloat.ie visitors recently will be aware of the remarkable photo of Blind Harbour on the Waterford coast which they obtained with their Warrior 40 Coire Uisge anchored in this extraordinary gap in the cliffs. But as this coastline is much transitted by the large fleets from the East Coast trying to reach the promised cruising land of the Southwest, the good news is that Dunmore East is dredged and looking forward to further developments which will be more friendly to recreational boat users, Kilmore Quay is better run than ever, a real trophy facility for Wexford County Council, and even the utterly utilitarian ferry port of Rosslare – sometimes a crucial facility for small craft trying to negotiate Ireland’s tricky southeast corner – has been showing a friendlier attitude to boats in need in recent summers.

And yes, I know that strictly speaking Rosslare is not on the south coast, let alone the west coast. But the fact that it gets included shows the generously informative approach which the Editor and his team have taken with this fine book, which retails at €33.75.

Buy the book HERE

Irish Cruising Comes Centre Stage In Howth Yacht Club

With last night’s Irish Cruising Club Annual General Meeting & Prize-Giving hosted at Howth Yacht Club, and this morning’s day-long ISA Cruising Conference at the same venue, centre stage has been taken by the silent majority – the large but distinctly reticent segment of the sailing population which emphatically does not have racing as its primary interest afloat. W M Nixon takes us on a guided tour.

The great Leif Eriksson would approve of some of the more adventurous members of the Irish Cruising Club. They seem to be obsessed with sailing to Greenland and cruising along its coast. And it was the doughty Viking’s father Erik Thorvaldsson (aka Erik the Red) who first told his fellow Icelanders that he’d given the name of Greenland to the enormous island he’d discovered far to the west of Iceland. He did so because he claimed much of it was so lush and fertile, with huge potential for rural and coastal development, that no other name would do.

Leif then followed in the family tradition of going completely over the top in naming newly-discovered real estate. He went even further west and discovered a foggy cold part of the American mainland which he promptly named Vinland, as he claimed the area was just one potential classic wine chateau after another, and hadn’t he brought back the vines to prove it?

In time, Erik’s enthusiasm for Greenland was seen as an early property scam. For no sooner had the Icelanders established a little settlement there around 1000 AD than a period of Arctic cooling began to set in, and by the mid-1300s there’d been a serious deterioration of the climate. What had been a Scandinavian population of maybe five thousands at its peak faded away, and gradually the Inuit people – originally from the American mainland – moved south from their first beachheads established to the northwest around 1200 AD. They proved more successful at adapting to what had become a Little Ice Age, while no Vikings were left.

Now we’re in the era of global warming, and there’s no doubt that Greenland is more accessible. But for those of us who think that cruising should be a matter of making yourself as comfortable as possible while your boats sails briskly across the sea in a temperate climate or perhaps even warmer for preference, the notion of devoting a summer to sailing to Greenland and taking on the challenge of its rugged iron coast, with ice everywhere, still takes a bit of getting used to.

Yet in recent years the Irish boats seem to have been tripping over each other up there. And for some true aficionados, the lure of the icy regions was in place long before the effects of global warming were visibly making it more accessible.

Peter Killen of Malahide, Commodore of the Irish Cruising Club, is a flag officer who leads by example. It was all of twenty years ago that he was first in Greenland with his Sigma 36 Black Pepper, and truly there was a lot of ice about. The weather was also dreadful, while Ireland was enjoying the best summer in years.

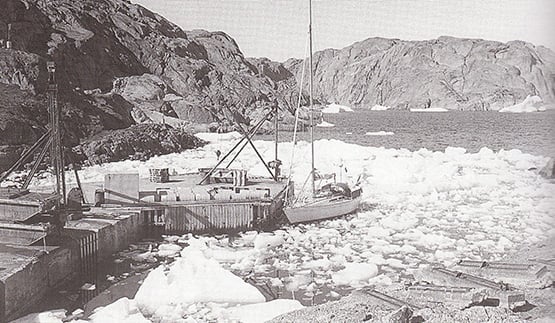

Peter Killen’s Sigma 36 Black Pepper in local ice at the quay inside Cape Farewell in Greenland, August 1995

ICC Commodore Peter Killen’s current boat is Pure Magic, an Amel Super Maramu seen here providing the backdrop for a fine penguin in Antarctica, December 2004.

More recently, he and his crew of longterm shipmates have been covering thousands of sea miles in the Amel Super Maramu 54 Pure Magic, among other ventures having a look at lots more ice down Antarctic way to see how it compares with the Arctic. With all their wanderings, by the end of the 2014 season Pure Magic was laid up for the winter in eastern Canada in Nova Scotia. So of course in order to get back to Ireland through 2015, the only way was with a long diversion up the west coast of Greenland. And the weather was grand, while Ireland definitely wasn’t enjoying the best summer in years.

The Pure Magic team certainly believe in enjoying their cruising, however rugged the terrain. If the Greenland Tourist Board are looking for a marketing manager, they could do no better than sign up the skipper of Pure Magic for the job. His entertaining log about cruising the region – featured in the usual impressive ICC Annual edited for the fourth time by Ed Wheeler – makes West Greenland seem a fun place with heaps of hospitality and friendly folk from one end to the other.

If ice is your thing, then this is the place to be – Peter Killen’s Pure Magic off the west Greenland coast, summer 2015.

But then Peter Killen is not as other men. I don’t mean he is some sort of alien being from the planet Zog. Or at least he isn’t so far as I know. But the fact is, he just doesn’t seem to feel the cold. I sailed with him on a raw Autumn day some years ago, and while the rest of us were piling on the layers, our skipper was as happy as Larry in a short-sleeved shirt.

I’d been thinking my memory had exaggerated this immunity to cold. But there sure enough in the latest ICC Annual is a photo of the crew of Pure Magic enjoying a visit to the little Katersugaasivik Museum in Nuuk, and the bould skipper is in what could well be the same skimpy outfit he was wearing when we sailed together all those years ago. As for the rest of the group, only tough nut Hugh Barry isn’t wearing a jacket of some sort – even Aqqala the Museum curator is wearing one.

Some folk feel the cold more than others – Pure Magic’s crew absorbing local culture in Greenland are (left to right) Mike Alexander, Peter Killen, Hugh Barry, Aqqalu the museum curator, Robert Barker, and Joe Phelan

Having a skipper with this immunity to cold proved to be a Godsend before they left Greenland waters, when Pure Magic picked up a fishing net in her prop while motoring in a calm. Peter Killen has carried a wetsuit for emergencies for years, and finally it was used. He hauled it on, plunged in with breathing gear in action, and had the foul-up cleared in twenty minutes. Other skipper and Commodores please note……

The adjudicator for the 2015 logs was Hilary Keatinge, who has one of those choice-of-gender names which might confuse, so it’s good news to reveal that after 85 years, the ICC has had its first woman adjudicator. No better one for the job, man or woman. Before marrying the late Bill Keatinge, she was Hilary Roche, daughter of Terry Roche of Dun Laoghaire who cruised the entire coastline of Europe in a twenty year odyssey of successive summers, and his daughter has proven herself a formidable cruising person, a noted narrator of cruising experiences, and a successful writer of cruising guides and histories.

Nevertheless even she admitted last night that once all the material has arrived on the adjudicator’s screen, she finally appreciated the enormity of the task at hand, for the Irish Cruising Club just seems to go from strength to strength. Yet although it’s a club which limits itself to 550 members as anything beyond that would result in administrative overload and the lowering of standards, it ensures that the experience of its members benefit the entire sailing community through its regularly up-dated sailing directions for the entire coast of Ireland. And there’s overlap with the wider membership of the Cruising Association of Ireland, which will add extra talent to the expert lineup providing a host of information and guidance at today’s ISA Cruising Conference.

But that’s this morning’s work. Meanwhile last night’s dispensation of the silverware – some of which dates back to 1931 – revealed an extraordinarily active membership. And while they did have those hardy souls who ventured into icy regions, there were many others who went to places where the only ice within thousands of miles was in the nearest fridge, and instead of bare rocky mountains they cruised lush green coasts.

Nevertheless the ice men have it in terms of some of the top awards, as Hilary Keatinge has given the Atlantic Trophy for the best cruise with a passage of more than a thousand miles to the 4194 mile cruise of Peter Killen’s Pure Magic from Halifax to Nova Scotia to Howth, with those many diversions on the way, while the Strangford Cup for an alternative best cruise goes to Paddy Barry, who set forth from Poolbeg in the heart of Dublin Port, and by the time he’d returned he’d completed his “North Atlantic Crescent”, first to the Faeroes, then Iceland to port, then across the Denmark Strait to southeast Greenland for detailed cruising and mountaineering, then eventually towards Ireland but leaving Iceland to port, so they circumnavigated it in the midst of greater enterprises.

You collect very few courtesy ensigns in the frozen north. Back at Poolbeg in Dublin after her “North Atlantic Crescent” round Iceland and on to Greenland, Paddy Barry’s Ar Seachran sports the flags of the Faroes, Iceland and Greenland. Ar Seachran is a 1979 alloy-built Frers 45. Photo: Tony Brown

“Definitely the Arctic”. A polar bear spotted from Ar Seachran. Photo: Ronan O Caoimh

Paddy Barry started his epic ocean voyaging many years ago with the Galway Hooker St Patrick, but his cruising boat these days is very different, a classic Frers 45 offshore racer of 1979 vintage. Probably the last thing the Frers team were thinking when they turned out a whole range of these gorgeous performance boats thirty-five years ago was that their aluminium hulls would prove ideal for getting quickly to icy regions, and then coping with sea ice of all shapes and ices once they got there. But not only does Paddy Barry’s Ar Seacrhran do it with aplomb, so too does Jamie Young’s slightly larger sister, the Frers 49 Killary Flyer (ex Hesperia ex Noryema XI) from Connacht, whose later adventures in West Greenland featured recently in a TG4 documentary.

“A grand soft day in Iceland”. Harry Connolly and Paddy Barry setting out to take on mountains in Iceland during their award-winning cruise to Greenland. Photo: Harry Connolly

Pure Magic and Ar Seachran are hefty big boats, but the other ICC voyager rewarded last night by Hilary Keatinge for getting to Arctic waters did his cruise in the Lady Kate, a boat so ordinary you’d scarcely notice her were it not for the fact that she’s kept in exceptionally good trim.

Drive along in summer past the inner harbour at Dungarvan in West Waterford at low water, and you’ll inevitably be distracted by the number of locally-based bilge-keelers sitting serenely upright (more or less) on that famous Dungarvan mud. There amongst them might be the Moody 31 Lady Kate, for Dungarvan is her home port.

But she was away for quite a while last year, as Donal Walsh took her on an extraordinary cruise to the Arctic, going west of the British mainland then on via Orkney and Shetland to Norway whose coast goes on for ever until you reach the Artic Circle where the doughty Donal had a swim, as one does, and looked at a glacier or too, and then sailed home but this this time leaving the British mainland to starboard. A fabulous 3,500 mile eleven week cruise, he very deservedly was awarded the Fingal Cup for a venture the adjudicator reckons to be extra special – as she puts it, “you feel you’re part of the crew, though I don’t think I’d have done the Arctic Circle swim.”

A long way from Dungarvan. Lady Kate with Donal Walsh off the Svartsen Glacier in northern Norway

Indeed, in taking an overview of the placings of the awards, you can reasonable conclude that the adjudicator reckons any civilized person can have enough of ice cruising, as she gives the ICC’s premier trophy, the Faulkner Cup, to a classic Atlantic triangle cruise to the Azores made from Dun Laoghaire by Alan Rountree with his van de Sadt-designed Legend 34 Tallulah, a boat of 1987 vintage which he completed himself (to a very high standard) from a hull made in Dublin by BJ Marine.

Tallulah looks as immaculate as ever, as we all saw at the Cruising Association of Ireland rally in Dublin’s River Liffey in September. And this is something of a special year for Alan Rountree, as completely independently of the Faulkner Cup award, the East Coast ICC members awarded their own area trophy, the Donegan Cup for longterm achievement, to Tallulah’s skipper. As one of those involved in the decision put it, basically he got the Donegan Trophy “for being Alan Rountree – what more can be said?”

The essence of the Azores. Red roofs maybe, but not an iceberg in sight, and the green is even greener than Ireland. Alan Rountree’s succesful return cruise to the Azores has been awarded the ICC’s premier trophy, the Faulkner Cup.

Tallulah at the CAI Rally in the Liffey last Setpember. She looks as good today as when Alan Rountree completed her from a bare hull nearly thirty years ago. Photo: W M Nixon

A boat to get you there – and back again. Tallulah takes her departure from the CAI Rally in Dublin. Photo: Aidan Coughlan

Well, it can be said that his Azores cruise was quietly courageous, for although the weather was fine in the islands, the nearer he got to Ireland the more unsettled it became, and he sailed with the recollection of Tallulah being rolled through 360 degrees as she crossed the Continental Shelf in a storm in 1991. But he simply plodded on through calm and storm, the job was done, and Tallulah is the latest recipient of a trophy which embodies the history of modern Irish cruising.

There were many other awards distributed last night, and for those who think that the ICC is all about enormous expensively-equipped boats, let it be recorded that the Marie Trophy for a best cruise in a boat under 30ft long went to Conor O’Byrne of Galway who sailed to the Hebrides with his Sadler 26 Calico Jack, while the Fortnight Cup was taken by a 32-footer, Harry Whelehan’s Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 32 for a fascinating cruise in detail round the Irish Sea, an area in which, the further east you get to coastlines known to very few Irish cruising men, then the bigger the tides become with very demanding challenges in the pilotage stales.

The smallest boat to be awarded a trophy at last night's Irish Cruising Club prize-giving was Conor O’Byrne’s Sadler 26 Calico Jack, seen here in Tobermory during her cruise from Connacht to the Hebrides

As for “expensively equipped”, the Rockabill Trophy for seamanship went to Paul Cooper, former Commodore of Clontarf Yacht & Boat Club and an ICC member for 32 years, who solved a series of very threatening problems with guts and ingenuity aboard someone else’s Spray replica during a 1500 mile voyage in the Caribbean, with very major problems being skillfully solved, as the judge observed, “without a cross word being spoken”.

Not surprisingly in view of the weather Ireland experienced for much of the season, there were no contenders for the Round Ireland cruise trophy, though I suppose you could argue that the return of Pure Magic meant the completion of a round Ireland venture, even if in this case the Emerald Isle becomes no more than a mark of the course.

In fact, with the unsettled weather conditions of recent summers in Ireland , there’s now quite a substantial group of ICC boats based out in Galicia in northwest Spain, where the mood of the coast and the weather “is like Ireland only better”. The ICC Annual gives us a glimpse of the activities of these exiles, and one of the most interesting photos in it is provided by Peter Haden of Ballyvaughan in County Clare, whose 36ft Westerly Seahawk Papageno has been based among the Galician rias for many years now.

Down there, the Irish cruising colony can even do a spot of racing provided it’s against interesting local tradtional boats, and Peter’s photo is of Dermod Lovett of Cork going flat out in his classic Salar 40 Lonehort against one of the local Dorna Xeiteras, which we’re told is the Galician equivalent of a Galway Bay gleoiteog. Whatever, neither boat in the photo is giving an inch.

So who never races? Dermod Lovett ICC in competition with his Salar 40 Lonehort against a local traditional Dorna Xeiteira among the rias of northwest Spain. Photo: Peter Haden

Hilary Keatinge’s adjudication is a delight to read in itself, and last night after just about every sailing centre in Ireland was honoured with an ICC award for one of its locally-based members, naturally the crews leapt to the mainbrace and great was the splicing thereof.

But it’s back to porridge this morning in HYC and the serious work of the ISA Cruising Conference, where the range of topics is clearly of great interest, for the Conference was booked out within a very short time of being highlighted on the Afloat.ie website.

It’s during it that we’ll hear more about that intriguing little anchorage which provides our header photo, for although it could well be somewhere on the Algarve in Portugal, or even in the Ionian islands in Greece were it not for the evidence of tide, it is in fact on the Copper Coast of south Waterford, between Dungarvan and Dunmore East, and it’s known as Blind Harbour.

It’s a charming place if you’ve very settled weather, but it’s so small that you’d probably need to moor bow and stern if you were thinking to overnight, but that’s not really recommended anyway. Norman Kean, Editor of the Irish Cruising Club Sailing Directions, had heard about this intriguing little spot from Donal Walsh of Dungarvan (he who has just been awarded the Fingal Cup), and being Norman Kean, he and Geraldine just had to go and experience it for themselves. But it has taken three attempts to have the right conditions as they were sailing by, and it happened in 2015 in a very brief period of settled weather as they headed past in their recently-acquired Warrior 40 Coire Uisge, which has become the new flagship of the ICC’s informal survey flotilla.

The secret cove is to be found on Waterford’s Copper Coast, midway between Dungarvan and Dunmore East. Courtesy ICC

The newly-surveyed Blind Harbour on the Waterford coast as it appears in the latest edition of the ICC’s South & West Coasts Sailing Directions published this month. Courtesy ICC.

They found they’d to eye-ball their way in to this particular Blind Harbour (there are others so-named around the Irish coast) using the echo sounder, as any reliance on electronic chart assistance would have had them on the nearest part of County Waterford, albeit by only a matter of feet. With a similar exercise a couple of years ago, they found that the same thing was the case at the Joyce Sound Pass inside Slyne head in Connemara – rely in the chart plotter, and you’re making the pilotage into “impactive navigation”.

The message is that some parts of charts are still relying on surveys from a very long time ago, and locations of hyper-narrow channels may be a few metres away from where they actually are. On the other hand, electronic anomalies may arise. Whatever the reason, I know that a couple of years ago, in testing the ship’s gallant little chart plotter we headed for the tricky-enough Gillet passage inside the South Briggs at the south side of the entrance to Belfast Lough, and found that it indicated the rocks as shown were a tiny bit further north than we were seeing, which could have caused a but of a bump if we’d continued on our electronic way.

Electronic charts are only one of many topics which will be covered today. We hope to bring a full report next Saturday, for the participants will in turn require a day or two to digest their findings.

Justin Slattery Awarded Top Irish Cruising Club Honour

Double Volvo Ocean Race winner Justin Slattery has been awarded the J B Kearney Cup by the Irish Cruising Club (ICC).

The J. B Kearney is awarded to individuals for their outstanding contribution to Irish Sailing. The committee unanimously agreed to award Justin the trophy in recognition of his two decades of racing at the highest level, including five Volvo ocean races and for being a leading Ambassador to the Irish sailing community.

It will be presented to him at the annual dinner of the ICC in Howth YC on February 19.

Well deserved Juddy - the man I never go to see without! @adorlog #goazzam https://t.co/PhThliIyvt

— Ian Walker (@ADORSkipper) December 10, 2015

#WaterSafety - The Government's 'Sea Change' consultation contained sobering statistics on boating fatalities in Irish waters, prompting calls for much tighter water safety regulation. But as Irish Cruising Club spokesman and Sailing Directions Editor Norman Kean writes, that view is not shared by all in the marine sector...

In June 2014, the Department of Transport issued a consultation document titled 'Sea Change', in which it was alleged that over an 11-year period, 66 fatalities had occurred on recreational craft. This represents 47% of all marine fatalities in the period, and the figure was widely and sometimes sensationally reported.

In light of that, it's worth examining the following extracts from the Irish Cruising Club's (ICC) submission to the department, which reflects an independent study of the original Marine Casualty Investigation Board (MCIB) reports:

The MCIB reports for the period 2002 to 2012 describe 42 incidents involving craft other than licensed commercial or fishing vessels. Presumably these are classified, by default, as leisure-related. These 42 incidents resulted in 51 deaths. We believe it is significant and worthwhile to note that 28 of these fatalities (55%) occurred when the purpose was not recreational boating per se. Twenty-two people lost their lives while out fishing, five while ferrying or as passengers, and one on a hunting trip by boat. The remaining 23 comprised eight kayakers/canoeists, three jet-skiers, five sailing and seven power-boating, each activity in these 23 cases being carried out for its own sake.

There is circumstantial evidence to suggest that of the 22 'recreational' fishing casualties, at least 10 may have actually been out for commercial purposes. The same applies to at least two of the 'ferrying' category. We have knowledgeable independent support for that view.

Sixteen casualties, including the eight kayakers, lost their lives in rivers or lakes, and 35 in tidal water.

Sixteen of the 51 deaths occurred between November and April, not a time of year normally associated with recreational boating.

Most incidents involved small open boats; all but five vessels were under seven metres in length. One of those five was a 7.3-metre undecked gleoiteog.

Perhaps the most telling statistic is that in 32 cases, lifejackets were inaccessible, faulty or badly adjusted, or not worn when they clearly should have been. This, and much else described in the MCIB reports, indicate a disturbing recklessness and lack of awareness on the part of the casualties and their companions.

The discrepancy between the figure of 51 deaths investigated by the MCIB and 66 quoted in the consultation document presumably reflects the inclusion of diving, surfing and sailboarding casualties as 'recreational craft' accidents. These do not fall within the remit of the MCIB, for a good reason: diving is a specialised skill, and accidents seldom if ever have anything to do with the operation or actions of the boat; while a surfboard is not a boat.

The submission also goes on to say that "almost every one of the [nine contributory causes listed in the consultation document] is in turn a result of the above-mentioned lack of awareness, and... if that lack could be adequately addressed, many issues like 'failure to plan journeys safely' and 'vessel unseaworthy, unstable and/or overloaded' would simply no longer arise. This is the commonplace observation of every skilled and experienced recreational sailor; we see it all the time."

Our point was – of course - that the representation of recreational sailing as being particularly hazardous was a grossly unfair interpretation of the statistics.

The ICC was the only yacht club in Ireland to respond (the ISA also sent in a submission) and the RNLI was the only other organisation not to take the department's figures at face value. There were 36 submissions in total, many of them from professional organisations such as the Harbourmasters, the Irish Lights, the Naval Service, the Irish Coast Guard and the Institute of Master Mariners. Almost without exception these bodies and individuals wanted leisure craft and their crews to be highly regulated, sometimes to an utterly draconian extent.

In general, none of their recommendations would have the slightest effect on accident rates or consequences unless implemented with a zeal worthy of the Taliban. What they would undoubtedly do is make life easier and less stressful for the watch officer on the bridge of a ship or in the coastguard station, which one can well understand.

It is worthy of note that the RNLI and Irish Water Safety shared our view that education was preferable to regulation.

Posthumous Irish Cruising Club Award for Joe English

#icc – At the Annual Dinner of the Irish Cruising Club held at the Royal Cork Yacht Club last Saturday night its Commodore Peter Killen presented the John B. Kearney Cup to the family of the late Joe English together with a citation which read as follows:

The John B. Kearney Cup: Awarded for outstanding contributions to Irish sailing:

To Joe English for an outstanding career as a word–class sailor sailor. He skippered NCB Ireland in the Whitbread Round The World race in 1989-90, took part in the same race on 'Tokio' in 1993-4, participated in many Admiral's Cup races and was involved in a winning America's Cup team. In 1979, while based in Sydney he competed in several major events including the Southern Cross and Kenwood Cup series. In 1980 he won the one ton sailing cup with Harold Cudmore on the Tony Castro designed 'Justine' and also won the two ton cup in Sardinia a week later. Joe was central to the development of the 1720 sportsboat. Diagnosed with early onset Alzheimers disease at age 51, he died at age 58 on November 4th, 2014.

Joe's wife, April, and son Robbie accepted the award on behalf of the family.

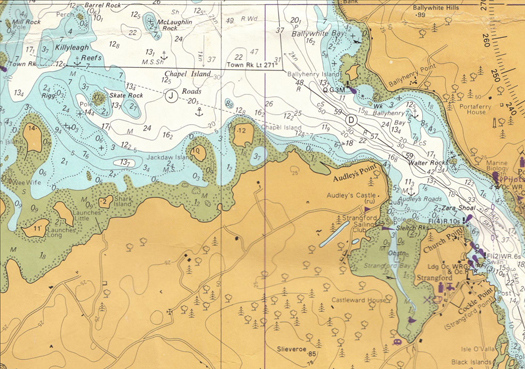

#eastcoastports – Ireland's east and north coasts may lack the cruising glamour of the south and western seaboards, but W M Nixon suggests that the ICC's East & North Coast Sailing Directions points the way to an area with its own special charms. And he ponders a coastal mountain-measuring quandary in this blog first published in March 2014.

Now here's a thought. Could it be that Scrabo, the tower-topped hill which dominates the northern waters of Strangford Lough, is not as high as officially reckoned? Could it be that its recognised height of 538ft (which doesn't include the 125ft height of the tower itself) is a bit optimistic?

Such notions come from contemplating aspects of the new 12th Edition of the Irish Cruising Club's Sailing Directions for the East & North Coasts of Ireland, which is now on sale at £29.95 or €37.50. It's worth every cent, not just for those planning to cruise the area, but simply if you sail from any of the ports covered. And the interest lies not just in the essential information conveyed for safe navigation and pilotage along these many miles of varied coastline, but also in the implications of that information in a larger context.

As the ICC publishes two books with the most recent massive 13th edition of its best-selling South & West guide appearing last year, inevitably people will compare the two areas. And equally inevitably, the east coast can appear a rather humdrum sort of place by comparison with the lotus-eating charms of the south coast, and the spectacular glories of the west, while the north coast sometimes seems just too challenging to be contemplated at all. However, in one category the east and north coasts put the south and west coasts in the ha'penny place. The eastern and northern seaboards are absolutely tops in tides.

On the west and south coasts, apart from the Shannon Estuary and maybe Achill Sound and perhaps Cork Harbour entrance at Springs, tidal streams are relatively weak on the entire coastline going westabout between Hook Head in Wexford and Bloody Foreland in Donegal. And yes, I too have shot the tidal rapids at Lough Hyne, but that's a special case. Otherwise, it's useful to have the tide with you along the coast, and it's best to avoid wind-over-tide at major headlands. But generally, unless you've a long passage planned you can come and go at sociable hours for day sails rather than having your schedule dictated by tide.

Yet if you're voyaging that same journey from Ireland's southeast corner to the far northwestern extremity via the east and north coasts with the absolute shortest distance being 282 miles, the tidal streams are dictating your times of coming and going except between Skerries and Ardglass on the east coast, and west of Malin Head on the north. Elsewhere, it's conveyor belt coastline, and anyone sensible will go with the flow.

Carlingford Lough is one of several inlets on these coastlines whose narrow entrances have strong tides. The mediaeval little township of Carlingford has its own largely drying harbour (foreground), but the marina further along the shore is accessible at all states of tides, and has facilities on site. However, village waterfront hospitality resources are somewhat spread out, as the hospitable Carlingford Sailing Club (extreme right), with its own slipway and welcoming clubhouse, is at a significant distance from the marina. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

In addition, where natural harbours and sheltered inlets exist, in a surprising number of cases on the east and north coasts the entrances are narrow, and pushing the tide to get through can be a serious challenge. This is the case in Mulroy Bay, Lough Foyle, Larne Lough, Strangford Lough and Carlingford Lough. But the great inlets of the west, particularly the magnificent rias of the southwest, are drowned river valleys which close in only gradually, resulting in much gentler tides.

Strangford Lough's entrance by contrast is totally tide-dominated, and many local cruising boats solve the problem simply by never leaving the place. But as a study of this new book (yet another extraordinary effort from the ICC's remarkable sailing directions team of Norman Kean and Geraldine Hennigan) successfully reveals, Strangford Lough is indeed a wonderful world unto itself, and you could happily cruise here for a week without feeling the need to venture into the dark unknown to seaward beyond The Narrows, where the tides hit 8 knots and more, and the whirlpool of the Routen Wheel waits to trap the unwary.

It's the business of the sea pushing in and out Strangford Lough twice a day (and generating electricity while it does so) which provokes the thought that maybe Scrabo is not as high as generally thought. The hill is simply known as Scrabo, which sounds like somewhere in Transylvania – it could be Dracula's summer residence - but apparently it means nothing more exciting than "cow pasture" in Gaelic. They were hardy cattle in them days, as it can be rugged enough on top, for Scrabo's location relative to the serene inner reaches of Strangford Lough emphasises its exposed nature.

Strangford Narrows, with a smooth yet powerful stream, though it can be anything but smooth when it meets open water and an onshore wind. The tides in the Narrows provide so much guaranteed energy that they have been harnessed by this generator to provide sufficient electricity for a thousand homes. Photo: courtesy ICC

The Seagen tower with its turbines raised clear. Like this, it can be a hazard for sailboats passing too close. Currently, the scorecard reads: Seagen-1, Yacht Masts-0. Miraculously, no-one was hurt. Photo courtesy ICC.

But the point is that high water in those remote inner reaches and in Strangford Lough generally occurs a clear two and a half hours after high water in the Irish Sea. Thus down at the Narrows, the water may be still pouring into the lough, yet out in the Irish Sea the tide has peaked, the ebb is running north, and the sea level has been falling for a good two and a half hours by the time the final surge has reached the top, way up at the flat shore below Scrabo.

So it occurs to me that, could we but somehow measure by the most precise methods exactly from the centre of the earth, then mean sea level at Scrabo would always be less – maybe even a metre less – than on the ocean generally. And for all hills, whether it be Scrabo or Everest or whatever, the height above sea level is the gold standard. So the surface of the sea must curve over and above the curvature of the earth.

My ignorance of modern surveying methods being almost total, doubtless this idle speculation will bring down scorn, and we'll find that crude measures of sea level by observation at a local position have been long since superseded by more scientific techniques. Probably these days sea level has little enough to do with the level of the sea. But if you're someone who likes to muse on such things as the true height of Scrabo in the light of Strangford Lough's wayward tides, then you've the mind of a cruising person, and you'll find the new guide a delight, particularly if you reckon the east coast has been getting a raw deal in the perception stakes.

The Economic Corridor. Dublin Port looking seaward at a quiet period between ship movements, which currently run at 40 per day. Grand Canal basin is bottom right, while the ancient maritime community of Ringsend is just across the River Dodder. The Dodder's east bank, now lined with corporation flats, used to be a hive of activity with at least four boatyards on the foreshore. Poolbeg Y & BC marina is beside Roingsend. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

That said, it has to be admitted that between Dublin and Belfast, the "East Coast Economic Corridor" may sound glamorous to business folk, but it can make it all seem rather workaday to the rest of us when sailing the nearby sea. Then too, the dictation of the tide in setting the times of your passage-making gives a sense that you're commuting along the coast, rather than cruising it. Finally, while there may be several handsome ranges of hills and mountain along both coastlines, only in certain areas is there significant indentation of the coastline to give that air of excited anticipation as to what might be round the next corner. By contrast in the south and west you've many variations on the sense of anticipation exemplified by the always uplifting experience of coming northwards through Dursey Sound and suddenly seeing the entire panorama of the Kerry mountains revealed in all their purple glory.

But living in such a state of constant excited anticipation would be damaging for anyone's health. The real business of life is making the best of the hand you've been dealt, and these days the east and north coast deal is much enhanced by greatly improved harbours and marinas. These make for much more convenient access to port towns, which in their turn provide a better hospitality package which adds greatly to the enjoyment of a day's sail along a coast which may have been looking very well indeed.

Not least of the factors in this is that, along the east coast at any rate, it rains less than on Ireland's other coastlines. Sometimes a lot less. And it's at its best when the wind is the Atlantic breeze, the westerly off the land. When "the wind is off the grass", as the crewmen in the Irish Lights vessel describe their ideal conditions for working at buoys and other navigation aids, then sailing Ireland's east coast is very pleasant indeed.

Although the east coast officially begins at Carnsore Point, the ICC Directions sensibly begin just round the corner at Kilmore Quay, whose transformation by Wexford County Council into a useful sailing/fishing harbour has greatly changed everyone's perception of the area. And just to show that the Saltee Islands can now be seen at the very least as an interesting day cruising destination from Kilmore itself, the book includes a useful photo of the fair weather anchorage on the southeast coast of the Great Saltee.

In times past, the Saltee Islands were seen by cruising folk as somewhere to get past as quickly as possible. But now that there's a fine little all-weather harbour and marina at Kilmore Quay, this photo of the fair weather anchorage off the southeast coast of the Great Saltee is of special interest. Photo courtesy ICC.

Heading up the east coast, the favoured first port of call tends to be Arklow, where developments in recent years have been an intriguing illustration of the way Ireland is administered. In any rational society, you'd have expected the Arklow Basin on the south side of the river – which has the benefit of having an exceptionally small tidal range – to be re-developed as a modern recreational harbour, a sort of Irish Honfleur.

But of course any attempts at this sensible line of action were stymied by inertia and entrenched interests, so the get-up-and-go section of Arklow society simply got on with things on the north side of the river. There, a marina has been developed in a new basin, and what amounts to a new township shows every sign of developing alongside it, while across the river the old basin slumbers on.

Arklow is home to an ancient seafaring tradition, manifested itoday in a vibrant locally-registered merchant fleet which operates internationally. The new harbour and waterfront development on the north bank of the river (left) proceeds crisply ahead while the old Arklow basin on the other side ponders it future. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

Undoubtedly the most exciting development on the east coast in recent years has been the creation of an all-weather harbour at Greystones, within easy sailing distance of Dublin yet just far enough to provide a sense of achievement. And there's a certain extra satisfaction in enjoying your breakfast aboard a cruising boat in the new marina while the commuter-filled DART trains trundle past headed towards the city, yet beyond in the morning sun the Wicklow hills look more beautiful than ever.

"Good morning, Greystones, how are you?" Breakfast on a cruising boat never tastes better than when you're in the new Greystones Marina with the early sun on the Wicklow hills, and a DART train filled with commuters heads for Dublin. Photo courtesy ICC

With the coastal developments of the last twenty to thirty years, the east and north coasts have now been reborn as sailing and cruising areas with the two main yacht harbours at Dun Laoghaire and Bangor, while there are now medium size marinas at Greystones, Poolbeg in Dublin, Howth, Malahide, Carlingford, Carrickfergus, Glenarm, Ballycastle, and Fahan on Lough Swilly.

Additionally there are the key smaller facilities at Arklow, Warrenppoint, Ardglass. Portaferry, Belfast Harbour, Rathlin Island, the Bann Estuary, Derry/Londonderry and Rathmullan, while convenient landing pontoons have been installed at several other sites. Details on all these and much more can be found in the new ICC book, but anyone cruising the region develops fondness for some favourite spot, and as someone who has been cruising up and down these coasts for a while now, I have to say that the facility which has most transformed the cruising is surely the little marina at Ardglass, officially known as Phenick Cove.

Kingpin harbour – Dun Laoghaire before the new "library" was erected at amazing speed in the middle of the waterfront. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

Ardglass. This little port has become one of the most useful of all, particularly for people who really do cruise. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

It is just so conveniently located, you don't have to deviate at all from the direct course up and down Ireland's East Coast, and the welcome provided by marina manager Fred and his array of amiable animals is second to none. Quite how we managed before Ardglass marina was installed I don't know any more. But I think it involved far too many unnecessary nights at sea, whereas now you can have a convenient overnight in a quirky place where – if you're minded to eat ashore – you can ring the changes between one of the best Chinese restaurants on the coast, or else the golf club in the castle makes sailors more than welcome, and if you've had enough of the salty sea for a while, a very short taxi ride takes you into the utterly and very aromatically rural heart of the country and steaks at Curran's foodie pub.

Bangor Bay's marina has settled in so well you could be forgiven for thinking the town was built around it. And you won't be surprised to learn that this part of North Down is known as the Gold Coast. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

When these ICC Directions first appeared in book form in 1946, they covered only the east coast, and that only between Carnsore Point and the little harbour of Carnlough on the Antrim coast. In those days, there were few if any facilities for cruising boats beyond it on the Irish coast, so it was seen as the best jumping-off port for people headed for the more civilised cruising on Scotland's west coast.

Ballycastle Harbour and marina required a king-size breakwater for full shelter, but its convenient location has been greatly beneficial for cruising the area. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

Thirty years ago, the notion of Rathlin Island as a popular cruising destination would have seemed absurd, yet the provision of a harbour has brought about a welcome change, and in summer there are always at least several (and often many) cruising boats in port. Photo courtesy ICC.

So it's around Ireland's northeast corner that the changes have been most beneficial, with a proper harbour at Glenarm and –miracle of miracles – a real harbour at Ballycastle. It has had to be built as a really massive affair, for you're now on the rugged north coast, but it has opened things up to great benefit, as it's a short day sail from the Hebrides, the charms of Rathlin Island with its excellent little marina are just across the Sound, and with the pressure taken off to get to any old harbour with some short of shelter, you can explore the Antrim coast at your leisure. You come away convinced that the famous Carrick-a-Rede rope bridge looks even more spectacular when seen from sea, yet equally convinced by Dr Johnson's famous comment that while the Giant's Causeway may be worth seeing, it's not worth going to see.

The north Antrim coast's famous Carrick-a-Rede rope bridge is best seen from a cruising boat. Photo: W M Nixon

Further along the north coast, there's excitement at Portrush as a 200 berth marina is planned for this key port. For anyone interested in harbour construction, it will be a fascinating project, for although Portrush is eastward of the most exposed point of all at Malin Head, it still manages to have truly ferocious sea conditions during winter storms. So the proposed new breakwater will have to be on mega-scale, but from a cruising point of view the provision of secure marina berths here will add an entirely new dimension. Portrush has direct rail connection with the rest of Ireland, and it provides the best departure port if you want to make a quick passage to the Outer Hebrides. A course from Portrush shaped to leave Skerryvore to starboard will take you neatly to Castlebay in Barra while leaving the inconvenient tides and turbulent waters of Islay well clear to the east, and the rough water north of Malin well away to the west.

Portrush as it is today. A plan for a 200 berth marina will necessitate an ambitious extension and reinforcement of the main breakwater. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

But for anyone cruising on towards north Donegal, those demanding waters off Malin Head are part of the challenge, and plumb in the middle of them is storm-racked Inishtrahull. Amazingly, in the long distant past this little island supported several families, but these days its deserted state would make you wonder at the ICC book's assertion that there's quite a decent anchorage at Portmore on the island's hyper-rocky northern coast. So just to show that there is indeed an anchorage here, the book features a photo of Portmore with a fine cruising yacht serenely in the midst of it.

Remote Inishtrahull, most northerly part of Ireland. Yet there is an anchorage here..............

.....and the ICC book has the photo to prove it. Photos courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer/Ed Wheeler

West of Malin, the majestic north coast of Donegal includes the entrances to many inlets, the largest being Lough Swilly which is about the size of the Solent. The main sailing base is at the sandy creek at Fahan on the east shore where the provision of a marina brought expectations of proper well-planned shoreside supporting development to take the raw look off the place, but disappointingly it hasn't happened yet. We can only hope that the success of local sailor Sean McCarter as a skipper in the current Clipper Round the World Race will inspire the Fahan area to finish the job.

A job that really ought to be finished properly. The marina at Fahan on the east shore of Lough Swilly in Donegal is badly in need of appropriate shoreside development. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

Further west, and its pure Atlantic, but relieved by remote and secure inlets. Nevertheless it's difficult to grasp that the secluded and forest-sheltered anchorage at lovely Ards on Sheephaven is only a very few miles from the storm-tossed rocks of Tory Island, but such is the case. At Camusmore on Tory, the tiny harbour seems to be hurricane-proof, for although it was in the most violently-assaulted of all areas on Ireland's west coast during the thirteen storms of the past rough winter, surprisingly Tory is not among the harbours listed for government largesse in the current tranche of funding for urgent repairs.

This snug tree-sheltered anchorage at Ards on Sheephaven does not accord with the popular perceptions of the rugged nature of North Donegal, yet here we see a lone cruising boat enjoying its gentle charms. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

It's bullet-proof, it's hurricane proof – it seems there was no need for the little nugget of a harbour at Camusmore on Tory Island to apply for emergency funding for any urgent repairs despite the winter-long assault by at least thirteen different storms. Photo: Courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

But Tory Island's nearest mainland quay at Magheraroarty is down for repair funding, and away to the far southeast at the crowded little harbour of Courtown in Wexford, they've a harbour which is down for more than €1 million in repairs expenditure. Courtown is a difficult one, a narrow little river port where life is a continuing struggle to keep the sand at bay, and yet stop the quay walls from being undermined. When you see what they had to do at Tory and Ballycastle to keep their harbours in place, you can't help but wonder if the sum allocated to Courtown is anything like enough, but at least official interest is being shown.

Courtown on Wexford's east coast is one of the harbours earmarked for urgent repair expenditure under this week's government scheme. Phot courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

Many years ago, Paddy Barry set out to cruise round Ireland in his Galway Hooker St Patrick without using any anchorages recommended in the Sailing Directions by his fellow members of the ICC. It was just possible back then, and he overnighted at sixteen different places which were "unexplored". It would be virtually impossible to do that today, but even so it's entertaining to see if some favourite little places, some unknown quirky spots, have somehow slipped under the ICC radar.

Has anyone overnighted there? The pool inside Chapel Island invites anchoring.

I can think of two, but have to admit that while I've seen them both, and seen boats in them, I've never taken a boat into either myself. One is a curious glaciated pool that is found behind Chapel Island in the southeast corner of Strangford Lough. At high water there's little enough shelter in the sound inside Chapel Island. But at low water, the classic Strangford Lough seabed emerges on either side, more than a metre high, while in the little pool you're lying in more than three metres. A couple of times I've seen a boat or two anchored in the area at high water while we've been hastening past entering or leaving the lough. But whether or not anyone has stayed on for the sweet entrapment at lower water I don't know, but would dearly like to hear from anyone who has.