#halfton – As we digest the multiple results of the Rolex Fastnet Race and run the effects of different measurement rules and allowance systems over the elapsed times of a fleet of almost absurd diversity, it is only natural to wish for some simple system whereby first past the post is the winner, and that would be the beginning and end of it. Yet there's something about offshore racing which makes the notion of using straightforward one-design boats a concept of only limited appeal. The sea itself is an environment of such diversity that it seems to call out for a variety of boats to sail upon it, while the people sailing those boats are of course ludicrously individualistic.

Not that there haven't been attempts over the years to introduce one design offshore racing classes. We'll see it again soon with the new Volvo boats, and at the moment the superb MOD 70s are showing just how attractive the one design ideal can be. But it's nothing new. In fact, the idea of one designs capable of going offshore racing goes back beyond the establishment of "ocean racing" as we know it in Europe today, and was in evidence in America when Thomas Fleming Day inaugurated American ocean racing with the first Bermuda Race in 1906 with three boats which were all totally different, and two of them finishing the course.

In the golden age of sailing development from around 1890 until the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, several noted designers and builders on both sides of the Atlantic produced one design boats which were capable of racing offshore. One of the first was the Belfast Lough Number One Class of 1897, designed by William Fife, the design (slightly modified) being adopted the following year as the Dublin Bay 25. At 37ft LOA and 25ft LWL with a proper if decidedly Spartan cabin, they had the potential to be fast cruisers which could be offshore racers.

The new Belfast Lough Number Ones racing in 1898. They had the potential to be one design offshore racers, but the sport hadn't yet been invented. Photo courtesy RUYC

Except that the concept of offshore racing as we know it today simply didn't exist. For sure, you'd things like the Royal Alfred YC's Channel Matches between Dublin and Holyhead from the 1870s onwards, and there were also some coastal passage races. Then too, boats like the Herreshoff-designed New York 40s could take part as a class in events like the NYYC annual summer cruise. But the notion of a one design boat which could perform well while staying at sea for prolonged periods with the crew sleeping on board - whether at sea or in port - was not really on the agenda at all until around 1909, when the designs for the 11-ton yawls of the Belfast Lough Island class were commissioned from Alfred Mylne of Glasgow.

The Belfast Lough Island Class yawl Eriska in 1911. This was one of the first serious attempts to create a one design cruiser-racer class. Photo courtesy RNIYC

This was to be a one design class which could be used for regular club racing while at the same time providing sufficient comfort for the annual two weeks cruise to the Scottish West Coast which was the staple of Belfast Lough sailing, with the additional option of taking on cross channel races to the Clyde or Portpatrick.

It was one very crowded design brief. And with half a dozen potential owners making their personal views felt, plus the fact that the builder was John Hilditch of Carrickfergus, who was no stranger to controversy, creating the new class was a tricky business.

The Island Class Trasnagh winning the cross channel race to Portpatrick in 1925 Photo courtesy RUYC

The offshore one design dream briefly fulfilled – five boats of the Belfast Lough Island Class in Portpatrick in 1925 after racing from Bangor. Photo courtesy RUYC

There's also a feeling that Alfred Mylne, arguably the best of the Scottish designers after the death of G L Watson in 1904, wasn't really giving the task his full attention. In response to the demand for a comfortable cruiser, he certainly designed a boat of considerably more displacement, proportionately speaking, than his racing one designs such as the Dublin Bay 21s. Yet if anything the new Island Class boats seemed to have lower freeboard than many Mylne designs of comparable size, and they undoubtedly were very low slung in their later years when auxiliary engines and other additional cruising comforts were added.

Thus in full cruising trim, they could be extremely wet to sail aboard. I can remember as a kid being on the old Island Class yawl Trasnagh as we went through the Ram Harry tide race northeast of the Copeland Islands at the entrance to Belfast Lough. It was a bit startling to be sitting in a cockpit suddenly full of water. But owner Billy Barnes was completely unfazed by this state of affairs – that's the way it was with the Islands, but it meant their self-draining cockpit was an essential.

Then too, while they may have been a gallant pioneering attempt to transfer the one design ideal to a cruiser-racer, being Belfast Lough the owner's group managed to fall out with the builder. Hilditch wanted £350 per boat, but the owners wouldn't go a penny over £345. The argument dragged on until eventually Hilditch said he would build the boats for £345, but their stems would have to be markedly snubbed in order to save money.

Presumably the original line of the stem was an elegantly drawn-out overhang in much the same style as the Dublin Bay 21. But nevertheless, how any money could be saved by making it an awkward little tight curve in a distinctly spoon bow profile is difficult to believe, and those not directly involved reckoned it was a classic case of cutting off one's nose to spite one's face.

Be that as it may, by 1913 the Islands had six boats racing, and they were an impressive sight in regular action off Cultra and Bangor, and at Belfast Lough regattas. Several also appeared at the Clyde Fortnight, taking the crossing of the North Channel comfortably if wetly in their stride. But the prospect of the continuing growth of the class was brought to a halt by the Great War of 1914-18, and after it the heart had gone out of much of sailing in the Belfast Lough area until things slowly picked up in the 1920s.

Wet but fast – Island Class yawl Trasnagh powering through Donaghadee Sound in 1933 under her new Bermuda rig Photo courtesy RNIYC

Like many other classes, the Islands faced demands for a changeover to Bermudan rig, and they suited it well, though when some owners went all the way and removed the little bowsprits in the interests of a more modern appearance, the result was a boat which hung on her helm like a ton of bricks.

Trasnagh entering Dun Laoghaire in 1980 in her later days under Bermuda rig and without the bowsprit, showing how little freeboard the boats had with an added auxiliary engine and other cruising equipment. In recent years she has been re-built in Devon, with her original gaff configuration restored. Photo: W M Nixon

By the 1930s, other areas were looking seriously at the notion of club one designs which could also race and cruise offshore, and the idea of the Bermuda-rigged Dublin Bay 24 was first mooted in 1934. Seldom can a class have had a longer gestation. This time it was World War 11 from 1939 to 1945 which brought things to a halt, and it was 1946-47 before the 24s were finally sailing on Dublin Bay, and starting to show their potential inshore and offshore.

Across in England, the members of the RORC in its early years after its foundation in 1925 were so individualistic that the notion of an offshore one design simply didn't arise. But then in the grim days of slow recovery after World War II, the great John Illingworth and others shook things up with the Laurent Giles-designed RNSA 24. With a transom stern making them not unlike large Folkboats, these 30 footers could have been a first offshore one design, but of course although the hulls were standard, everything else was different – Bill King, for instance, even rigged his RNSA 24 Galway Blazer as a ketch.

However, there was one little germ of an idea floating around which began to gain adherents, and that was level rating racing. By all means have different boats, but have them designed to rate under the RORC rule to exactly the same rating. It would encourage design development, yet it would produce an immediate winner. It seems such an obviously sensible notion that it's extraordinary to think its appeal is not universal. Yet people are always trying to find ways of shaving a point or two off their rating and getting every advantage from this. And as for boats which simply cry out to be straightforward offshore one designs, such as the great First 40.7, it emerges that few if any of them rate exactly the same.

Nevertheless the level rating ideal goes up the flagpole every so often, and in 1965 it took off in a big way with the re-allocation of a silver cup presented in 1899 by the Earl of Granard (he was to become Commodore of the National YC in 1930) to the Cercle de la Voile in Paris. Initially, the One Ton Cup was for racing on the Seine, then it was raced for by the International 6 Metre Class, and then in 1965 it found new life for an international series, inshore and offshore, for offshore racers rated at 22.0ft under the RORC Rule.

At this distance, it's difficult to imagine the excitement aroused by this new shine on the old cup. Some well-known offshore racers had some very odd things done to them in order to make them fit the very specific rating. But it worked, the idea took off big time, and the spinoffs soon followed. One Tonners were boats around 35-36ft long, Half Tonners which soon followed were 28-31ft, Three Quarter Tonners were 32-34ft, Quarter Tonners were around 25ft, and Two Tonners were 40 – 42ft. They all raced absolutely level in their class, first to finish was the winner, that was all there was to it, and for about twenty years this was the most exciting area of offshore racing.

Irish sailing was much involved, and over the years it was with the Half Ton Cup – boats around the 30ft mark – in which we made our greatest impact. The arrival of Ron Holland in Cork in 1973-74 provided the necessary design skills, and in 1976 Harold Cudmore and a Cork crew went forth on a somewhat shoestring challenge to the Half Ton Worlds in Trieste with the new Silver Shamrock, a re-worked version of the original Ron Holland Golden Shamrock production Half Tonner concept from 1974.

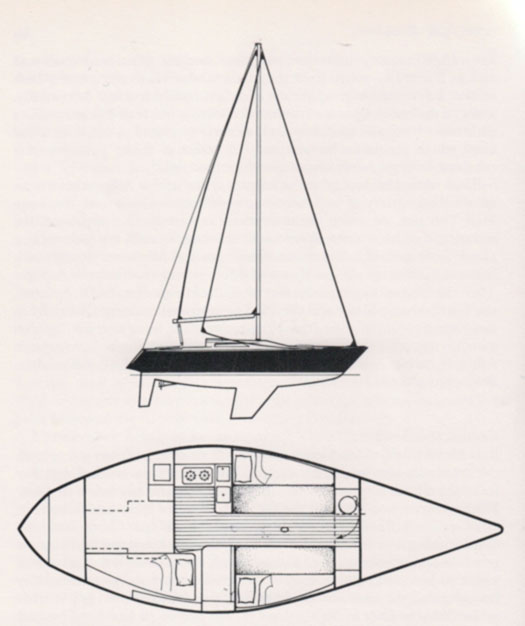

Golden Shamrock, built in Cork, was Ron Holland's first production Half Tonner

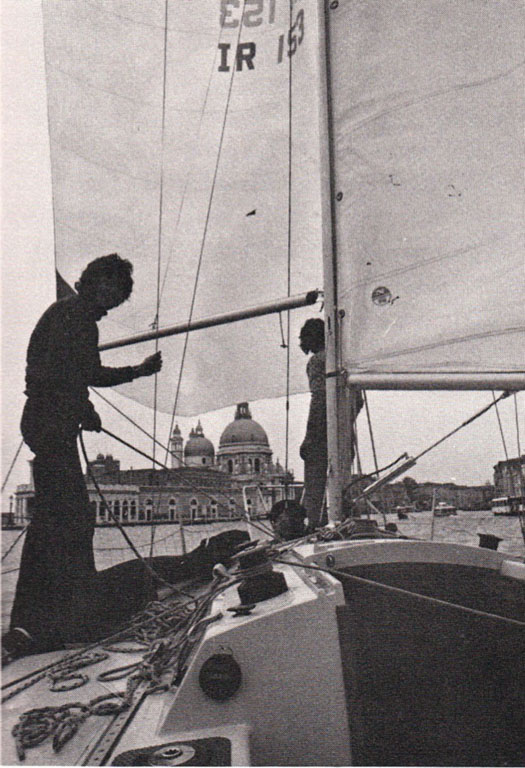

Victory parade. After Silver Shamrock won the Half Ton Worlds at Trieste in 1976, she sailed across to Venice and ran up the Grand Canal under spinnaker. Ronnie Dunphy on left of photo, Killian Bushe behind mast.

Harry Cudmore won a famous victory, and in celebration he and his crew sailed across to Venice and ran up the Grand Canal with spinnaker set. It was his first major international success in what was to become a glittering global sailing career, and as for the Half Tonners, they were firmly set on course to become the most popular of the Ton Cup classes.

During the 1970s and early '80s, fleet numbers were regularly pushing over the 40 mark at the annual World Championship, and though the peak had been 55 boats at Marstrand in Sweden in 1972 (when Paul Elvstrom won), they were still around the 40 mark in the early 80s, and could muster 35 at Porto Ercole in 1985.

The waxing and waning of particular kinds of racing is sometimes incomprehensible. But whatever caused it, the collapse of the Half Ton Worlds as a premier event was sudden and total. There were hundreds of eligible boats around, but with the economic gloom of the 1980s and people's sailing interests focusing elsewhere, as an event the Half Ton Worlds fell off a cliff, with the last one in 1993 at Bayona attracting just ten boats.

The event may have gone, but the many and often gorgeous boats were still very much in existence, increasingly seen as classics, and raced in handicap classes by devoted owners. In 2000 at Cork Week, two of them – the Irish boat SpACE Odyssey (Shay Moran, Enda Connellan, Terry Madigan and Vincent Delany) and the French boat Sibelius (Didier Dardot) decided that a Half Ton Classics Worlds, limited to boats built to the relevant rule between 1967 and 1992, might just be a runner on a biennial basis, and it has proven itself so, with entries two years ago in Cowes topping the 38 mark.

In 2007, it came to Dun Laoghaire with 25 boats providing a feast of nostalgia and great sport. The overall winner was the Rob Humphreys-designed one-off Harmony, owned by Nigel Biggs, who became so hooked on the value of the concept incorporated in this re-birth of the Half Tonner notion that he bought a vintage Humphreys-designed production boat, an MG30, and set about optimising her for racing in a class which is keen enough to make it worth the effort, yet not so excessively competitive as to self-destruct.

The result of the optimisation, which began with a consultation with David Howlett followed by a permitted redesign of the keel and rudder by Mark Mills, with all the ideas then implemented by John Corby at his yard in Cowes (with some of his own notions added), is of course Checkmate XV, the runaway superstar of the Volvo Dun Laoghaire regatta in July, and surely one of the favourites for the Half Ton Classics 2013 which gets under way tomorrow at Boulogne in northern France.

For this event, Biggs' crew reflects his active involvement in sailing on both sides of the Irish Sea. From this side of the Irish Sea, he has recruited regular shipmates Jimmy Houston from RStGYC and Robbie Sargent from Howth, while the other side of the channel brings in longtime sailing friend Pete Evans (they go back to Laser Youth Racing in 1985), and George Rice and Gerry Ibberson.

Since the VDLR in July, Checkmate XV has been undergoing further tuning in her home shed in Cowes, with a smidgin being shaved off her IRC rating. For yes, it has to be admitted that, with the age range of the Half Ton Classics taking in such a wide band from 1967 to 1992, they actually race under IRC on a handicap basis. It sounds crazy. But it works, and the reality is that there isn't more than 30 seconds in any hour between the class rating extremities.

King One for the road, and easily trailed with it – Dave Cullen's former world champion King One will also be at the Half Ton Classics in Boulogne, and has already been successful in the area with a win at Ramsgate Week last year. Photo: W M Nixon

Most of the classic Half Tonners from the era when the class was at its frontline international height are attractive boats, and they're of very manageable size while providing a bit of muscle. Trailering them is a straightforward proposition, and another entry tomorrow of special interest, Dave Cullen's King One from Howth, has made a speciality of sailing in those narrow easterly waters of the English Channel, where she was a participant last year in Ramsgate Week, which she won.

After more than a decade as a biennial event, the Half Ton Classics will now go annual, with 2014's championship already scheduled for Carnac in Brittany. We wish it well. We may have set out this week to follow the storyline of the once fervent hope that there could be genuine one design offshore racers, a hope so continually frustrated that instead people turned to the scope offered by designing different boat to fit one rating band. We have continued our voyage of discovery to find that boats of what was once the world's most numerous level rating class are so different - when all eras are brought together - that the only way they can have meaningful racing is by using the IRC handicap system, just like everyone else. Crazy maybe. But no crazier than the America's Cup.