Displaying items by tag: Poolbeg Yacht and Boat Club

Dublin Bay Sailing Partnership Based on Artistic Endeavour

#iris – It has been said that keeping a boat-owning partnership intact is much more difficult than maintaining a marriage in a healthy state. Thus for most of us with the boat-owning vocation, sole ownership is the only way to go. But for others, in order to defray costs, increase boat size, and maybe leave more personal time free to pursue other interests, the ambitions can best be realised through one of a wide variety of partnerships and syndicates.

These can go through an extensive range, starting at one extreme with what amounts to time-sharing, with the large number of owners meeting (if they meet at all) only once a year for a sort of Annual General Meeting. Other possible setups can mutate through various arrangements where there is considerable overlap between the boat uses by the different owners, right through to the other extreme of total partnership where all owners sail together as often as is possible.

In some cases, the additional social glue of special shared interests is needed to give the partnership that essential extra vitality. There's nothing new in this. W M Nixon takes a look back a hundred years and more to a boat-owning group whose shared interest in art kept a 60ft ketch on a regular cruising programme around Dublin Bay and the nearby coastlines.

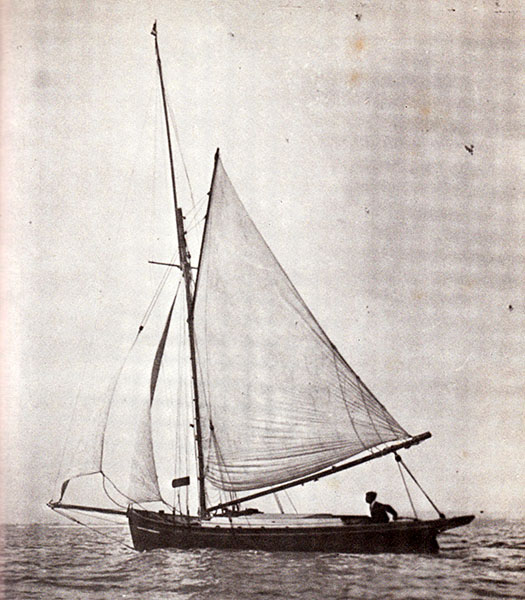

The 60ft gaff ketch Iris had a chequered career. She started life at the peak of the Victorian era in the 19th Century as a naval pinnace serving Dublin Bay, and she was presumably driven by steam. At the time, Dun Laoghaire – then known as Kingstown – was becoming the height of fashion as a naval port of call in the summer, made even more so by its convenient access to the centres of power in Dublin, and its strategically useful direct rail connection – pierhead to pierhead – to the main Royal Navy base in Ireland at Cobh on Cork Harbour.

However, as Kingstown had initially been planned solely as a harbour of refuge – an asylum harbor - for ships in distress in onshore gales, with the actual spur to its construction (starting in 1817) being the wrecking of a British troopship with huge loss of life at Seapoint on the south shore of Dublin Bay, the plans had included no provision for convenient alongside berthing for ships.

Indeed, you get the impression that the original underlying thinking was that there should be as little social contact as possible between ships sheltering in the new harbour and any inhabitants of its nearby undeveloped shore. But the rapid if somewhat chaotic growth of the makings of a new harbourside town, plus the advent of more rapid access from Dublin with the coming of the railway in 1834, soon meant that the top brass expected to be able to get off and on their ships in the harbour in style and comfort, and their Lordships of the Admiralty did not stint in providing large pinnaces for them to do so. When these pinnaces were replaced in due course by even more luxurious vessels, those shrewd amateur sailors who could visualise the older boats' potential as re-cycled government surplus found themselves looking at a bargain.

The Iris was originally built with lifeboat-style construction of double-diagonal hardwood planking, which was quite advanced technology for the time. For the can-do boatbuilders of the late 19th Century, converting such totally purpose-built craft into some sort of a yacht was all part of a day's work. Another similarly-built if smaller and different-shaped vessel, Erskine Childers' Vixen on which the Dulcibella of The Riddle of the Sands fame was based, was formerly an RNLI lifeboat with the standard lifeboat canoe stern. She was made more yacht-like by the addition of a staging aft to compensate for the absence of deck space just where you most need it, while underneath this new permanent staging, additional supporting planking was faired into the hull and – hey presto – you've a yacht-like counter stern.

Vixen also had a massive centre-plate complete with its huge casing, and carried more than three tons of internal iron ballast, all of which left little enough space for living aboard during the long and often rough cruise through the Friesian Islands which provided much of the on-the-ground material – and we can mean that in every sense – on which The Riddle was based.

Erskine Childers' Vixen (on which "Dulcibella of The Riddle" was based) in one of his last seasons of ownership in 1899. At first glance, she looks like a typical old-style cruising cutter of her era. But somewhere in there is a classic canoe-sterned RNLI lifeboat hull to which an afterdeck on a counter stern have been fitted as an add-on.

That cruise was in 1897, and shortly after it was completed, Childers went off to serve in the Boer War. This experience left him with doubts about the validity of the British Imperial mission, but equally left him in no doubt that on active service, there were no medals for enduring unnecessary discomfort. So by the time The Riddle of the Sands was published in 1903, Vixen was sold and he'd become a partner in a much more comfortable cruising boat, the yawl Sunbeam, which in turn was followed in 1905 by his very comfortable dreamship Asgard

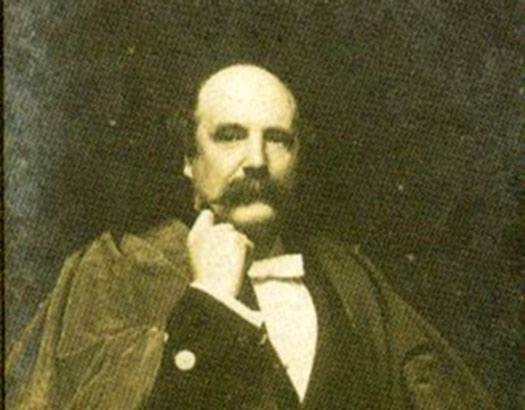

Meanwhile, with the Iris a fifteen or so years earlier in Dublin, the conversion to a comfortable sailing cruiser was a more straightforward affair, as she'd a more versatile hull shape with a broad stern in the first place, and her new owner was one George Prescott, an innovator bordering on genius. He was an optical and scientific instrument maker, an electrical engineer and inventor, and a state-of-the-art clockmaker.

Man of many parts – the polymath George Prescott. Organising the Graphic Cruising Club and running its club-ship Iris was only one of his many interests. He led a long and extraordinarily interesting and varied life, and was nearly a hundred years old at the time of his death in 1942. Courtesy Cormac Lowth

But that was only one part of his life, for he had many friends among Dublin artists, particularly those interested in maritime topics, and he soon found himself to be the secretary of the Graphic Cruisers Club for sailing painters and sketchers, with the Iris becoming the base of their waterborne creative and scientific expeditions on the coast of the greater Dublin area.

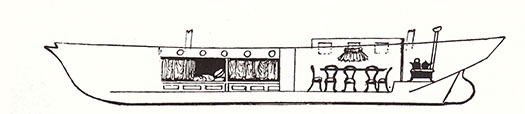

She was ideal for this. She'd been converted for sailing with an orthodox gaff ketch rig, while her roomy hull was internally re-configured to have a galley with a large stove right aft, a huge saloon immediately forward of the galley to be both the clubroom and dining room, and sleeping quarters port and starboard in pilot cutter style forward of that.

Quite a transformation for a former steam-powered naval pinnace. The 60ft ketch Irish in her heyday as the club ship of the Graphic Cruisers Club in the 1890s. She is at her home anchorage off Ringsend, while across the Liffey a couple of Ringsend trawlers are lying in the roadstead known as Halpin's Pool, where the Alexandra Basin is now located. Photo courtesy Cormac Lowth

Accommodation profile of the Iris in her days as the floating HQ of the Graphic Cruisers Club – this sketch by Alexander William first appeared in The Yachtsman magazine in 1894.

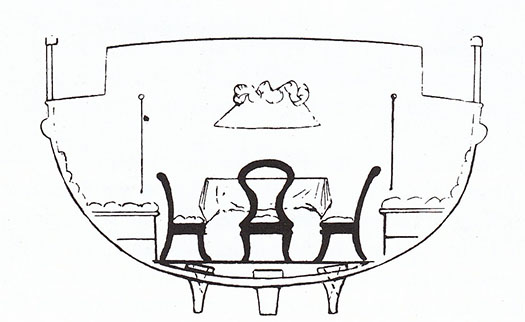

Hull section of the Iris at the saloon, showing the bilge keels which enabled her to dry out comfortably in some some little-known tidal anchorages in the Greater Dublin area.

But underneath the hull, the temptation had been resisted to add a deep keel, and instead the Iris was fitted with substantial bilge keels at the same depth as the shallow keel itself, such that in all she drew only about 3ft 6ins, and would comfortably dry out in a snug berth anywhere that her artistic crew felt they might find subjects worthy of their attention.

Thus she might overnight serenely on the beach at Ireland's Eye or far up the estuary at Rogerstown, and if the Graphic Cruisers Club attention was turned towards County Wicklow, she could comfortably take the ground in Bray or in other little ports inaccessible to orthodox cruising yachts. Yet the claim was that despite the odd arrangements beneath the waterline, she handled remarkably well on all points of sailing, and certainly as she no longer had any sort of engine, she must have sailed neatly enough to get out of some of the confined berths into which her eccentric crew enjoyed putting her.

The Iris in gentle cruising mode off Ireland's Eye as the moon rises – this was sketched by Alexander Williams for The Yachtsman in 1894.

George Prescott seems to have been happy to claim that Iris was a club-owned yacht, but in truth most of his shipmates were impecunious artists of varying talent, so it was his generosity and understated business ability which would have kept the partnership together.

However, it really did seem to function as a partnership, for after the Iris project had been up and running for nearly a decade, he turned his attention in 1896 to building an unusual house on the waterfront on the Pigeonhouse Road in Ringsend, which he happily acknowledged to be the clubhouse of the Graphic Cruisers Club even if he lived in it himself.

Called Sandefjord for some reason which is still unexplained, it looked not unlike a smaller sister of the Coastguard Station next door, complete with a lookout tower. And it's distinctly nautical within, as much of the interior includes fine panelling which came from the wrecked Finnish sailing ship Palme, with the stairs being provided by the old ship's main companionway.

The house called Sandefjord near Poolbeg Y & BC as it is in 2015. When built by George Prescott in 1896, it faced across the Pigeonhouse Road directly onto the waterfront, and overlooked the summer anchorage of the Iris. Photo: W M Nixon

The design style of the Graphic Cruisers Club shore HQ at Sandefjord reflected the lookout tower of the old Coastguard Station next door. Photo: W M Nixon

The house has been restored to become a family home in recent years, and it really is an extraordinary piece of work to come upon on the slip road down to Poolbeg Yacht & Boat Club. Meanwhile, interest in the doings of the Graphic Cruisers Club has been restored by the formidable research talents and tenacity of Cormac Lowth, who single-handedly does more work in uncovering unjustly ignored aspects of Dublin Bay's maritime life in all its variety than you'd get from an entire university department.

I first came across a reference to the Graphic Cruisers Club years ago in an article in an 1894 issue of The Yachtsman magazine, written by Alexander Williams (1846-1930), who was probably the club's most accomplished marine artist. But that was then, this is now, and it has taken Cormac Lowth's dedication in recent times to get the extraordinary setup around George Prescott and Alexander Williams and their friends and shipmates into the proper context.

Alexander Williams RHA was the best-known artist in the Graphic Cruisers Club. A taxidermist of international repute, he was also a noted ornithologist, and his interest in maritime subjects was matched by his enthusiasm for landscape. He was one of the first artists to "discover" Achill Island in the west of Ireland, and in time he created a remarkable garden there in a three years project in which he personally worked shoulder-to-shoulder with the build team.

A classic Alexander Williams portrayal of the trawlers of Ringsend with other shipping in the Liffey. Thanks to research by Cormac Lowth, we are now aware of how the style of the Ringsend sailing trawlers came about through links, between 1818 and the 1914 outbreak of Great War, with the pioneering fishing port of Brixham in Devon, which was the most technologically advanced fishing port in Europe in the mid 1800s. Courtesy Cormac Lowth

They were larger than life, every last one of them, and Prescott and Williams in particular were renaissance men who could turn their hand to any number of creative projects at a time when life around Dublin was fairly buzzing for those with the energy and interest to enjoy it.

And there were links to other aspects of Dublin waterfront life which have a further resonance. Back in January, I'd to give one of the supper talks at the National YC in Dun Laoghaire, and on this occasion the topic was John B Kearney (1879-1967), the Ringsend-born yacht designer and boatbuilder who was the club's Rear Commodore for the last 21 years of his life.

You need some sort of special little link to bring these talks to life, but fortunately I remembered that there's a fine big Alexander Williams painting of sailing trawlers at Ringsend in the NYC's dining room. I didn't know its date as we headed round the bay on the night of the talk, but we struck gold. It was dated 1890.

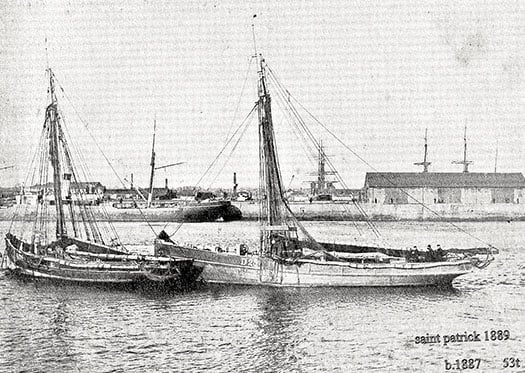

The Brixham style in Ringsend was best exemplified by the largest trawler built in the Dublin port, the St Patrick (right) of 53 tons built in 1887 in the Murphy family's boatyard beside the mouth of the River Dodder. The Murphy family also owned and operated the St Patrick in her fishing, and when John Kearney built his renowned yachts, the earliest (and best) of them were built in a corner of Murphy's Boatyard - the Ainmara in 1912, the Mavis in 1925, and the Sonia in 1929. Photo courtesy Cormac Lowth

Williams was so fond of the Ringsend scene that he lived there for a while in Thorncastle Street where John B Kearney was born, and of course the painter subsequently sailed regularly from the old port in the Iris, and would have over-nighted at Sandefjord too. He is in fact the definitive Ringsend maritime artist, and the picture in the NYC expresses this. And as it includes some of the Ringsend waterfront, we could say that it also includes John B Kearney, for in 1890 the precocious eleven-year-old Ringsend schoolboy was in the boatyards as much as possible, as he had already stated in his quietly stubborn way that his ultimate ambition was to be a yacht designer.

Not a boatbuilder or a shipwright or a harbour engineer, which is nevertheless what he was until he retired in 1944. But upon his leaving the day job - in which he'd been highly respected - he then devoted all his energies to what he had been doing all his life in his spare time. And with his death aged 88 in 1967, his gravestone in Glasnevin cemetery said it all: John Breslin Kearney (formerly of Dublin Port & Docks Board) Yacht Designer.

And if you wonder how on earth we have come to a consideration of John Kearney's memorial stone in an article which purports to be about the social glues which keep boat partnerships in good order, believe me when you get involved with the boys of the Graphic Cruisers Club you never know where it's all going to end.

We've already discovered that in later life Alexander Williams devoted much energy to his garden in Achill while at the same time continuing to be an active member of the Royal Hibernian Academy in Dublin. As for George Prescott, he too broadened his already extensive interests, and in his eighties he was much into amateur opera production, even being so deeply involved as to paint the stage scenery himself.

Dublin too was expanding, so he accepted that a move eastward was needed if he was going to be able to continue to commune directly with his beloved sea. So he left Sandefjord, and the final decades of his wonderful life were spent at his new home at The Hermitage on Merrion Strand. Needless to say, Alexander Williams provided him with a painting of The Hermitage which captured the then unspoilt nature of a place you'd scarcely recognize today.

The Hermitage on Merrion Strand, George Prescott's last home as portrayed by Alexander Williams. Courtesy Cormac Lowth

Go LulaBelle! How Ireland Won The Round Britain & Ireland Race

#rorcsrbi – For twelve days, Ireland's sailing and maritime community followed with bated breath while the fortunes of Liam Coyne and Brian Flahive with the First 36.7 Lula Belle waxed and waned in the storm-tossed 1802-mile RORC Sevenstar Round Britain & Ireland Race. Last Saturday, they triumphed, winning the two-handed division and two RORC classes in this exceptionally gruelling marathon. W M Nixon delves into the human story behind the headlines of success.

It used to be said that Irish seamanship was the skilled and stylish extrication of the vessel from an adverse and potentially disastrous situation in which she and her crew shouldn't have been next nor near in the first place.

While we may have moved on a bit from that state of affairs with a less devil-may-care approach to seafaring, there's no escaping the fact that this morning we can now look back at two remarkable Irish victories in topline international offshore events in recent years in which both crews overcame major setbacks and situations, rising above very adverse circumstances which could well have deterred sailors from other cultures where the philosophy is not underpinned by the attitude: "Ah sure lads, things aren't good. Not good at all. But let's just give it a lash and see how we go".

It was seven years ago when a full entry list of 300-plus boats was slugging westward down the English Channel in the first stages of the Rolex Fastnet Race 2007. Already, the start had been postponed 24 hours to allow one severe gale to go through. But in an event still dominated by the spectre of the 15 fatalities in the storm-battered 1979 race, most crews were hyper-nervous about another gale prospect, and by the time the bulk of the fleet was in the western English Channel, many succumbed to the allure of handy ports to lee such as Plymouth, and in those early days of the race something like 48% of the fleet retired.

But aboard Ger O'Rourke's Cookson 50 Chieftain out of Kilrush on the Shannon Estuary, they were well into their stride. That year, the boat had already completed the New York to Hamburg Transatlantic Race, placing second overall. But owing to her Limerick owner's quirk of never confirming the boat's entry for the next major event until the current one is finished, they found themelves only on the waiting list for that year's already well-filled Fastnet Race entry quota.

Chieftain was 46th on that list. Yet while those who had made an early entry fell by the wayside, steadily this last-minute Irish star rose up the rankings. With three days to go, Chieftain got the nod. They went at the racing after the delayed start as though this had been a specific campaign planned and carefully executed over many months with a full crew panel, instead of a last-minute rush where crew numbers were made up by a couple of pier-head jumpers who proved worth their weight in gold.

Yet then, as the new strong winds descended on the fleet as the group in which Chieftain was already doing mighty well was approaching the Lizard Point, the troubles started, with gear failing and boats pulling out left and right. But the Irish boat was only getting into her stride. A canting-keeler, she could be set up to power to windward in a style unmatched by bigger craft around her. Approaching the point itself in poor visibility to shape up for the fast passage out to the Fastnet Rock with even faster sailing, things looked good. And then the entire electronics system aboard went down, and stayed down.

Here they were, not even a third of the way into a race which promised to be rough and tough the whole way, but a race in which they would at least have been expecting know their speed, performance and position down to the most minute detail. Instead, they were in an instant reduced to relying on a couple of tiny very basic hand-held GPS sets, and paper charts.

Ger O'Rourke's Chieftain sweeps in to the finish at Plymouth to win the 2007 Rolex Fastnet Race overall

Those paper charts were little better than pulp by the end of a very wet race in an inevitably extremely wet but searingly fast boat. But they did get to the end, and with style too. They won overall and by a handsome margin. It was the first-ever Irish total victory in the Grand National of Ocean Racing. The owner-skipper had to go up the town to buy himself a clean shirt for the prize-giving in the Plymouth Guildhall.

Yet when Ger O'Rourke's Chieftain swept into Plymouth and that triumph just over seven years ago, the boat was in much better racing shape than Liam Coyne's First 36.7 Lula Belle when he and Brian Flahive completed the final few miles back into Cowes around midday last Saturday to finish the 1802-mile Sevenstar Round Britain & Ireland Race.

Lula Belle had many gear and equipment problems after an extreme event where the natural pre-start nervousness had been heightened by a reversal by the Race Management of the originally clockwise course as the 10th August start day approached. It would have been folly to send the fleet westward into storm force westerlies in restricted waters. Eastward was the only sensible way to go.

Then the arrival of the remains of Hurricane Bertha – which seemed to be finding new vigour – led to new tensions with the start being postponed from midday Sunday to 0900 Monday. It was disastrous from a general publicity point of view. But it would have been irresponsible to send a fleet of boats – some of them mega-fast big multihulls – hurtling towards the ship-crowded narrows of the Dover Straits beyond the limits of control in a Force 11-plus from astern.

Even when they did race away, it was with a Force 8 plus from the west, with the Irish crew recording 42.5 knots of wind aboard Lula Belle (and from astern at that), before they lost all their instruments from the masthead on the first night out. For a double-handed crew, that was a very major blow. Two-handers are allowed to use their auto-pilot, and if all the wind indicators are functioning in proper co-ordination with it, then the boat can sail herself along a specific setting on the wind. It's as good having at least one extra hand – and a skilled and tireless helmsman at that - on board.

Lula Belle on her way out of the Solent with 1800 miles to race and everything still intact. Photo: Rick Tomlinson

There it was – gone. After the first night at sea, Lula Belle's masthead was bereft of everything except an often defective Windex. Photo: W M Nixon

Fortunately the auto-pilot itself was still working on its own, and they became well experienced in setting the boat on course and then trimming the sails to it in a continuous process which worked well except when the seas were so rough and irregular that they had to hand steer in any case, albeit with the apparent wind indicated only by the sole survivor of the masthead units, the little standard Windex. But it must have been damaged when everything else was swept away, as from time to time it jammed. When that happened, the only wind indicators available to the two men were the Sevenstars battleflag on the backstay, the tell-tales on the sails, or a moistened finger held aloft, as neither were smokers.

Despite this, they made their way north through the North Sea and all round Scotland and its outlying islands and right down the western seaboard of Ireland as far as the Blaskets before things went even more pear-shaped. In fact, the wheels came off.

Their ship's batteries had been showing increasing reluctance to hold power, essential for the continuing use of the autohelm and the most basic need for lighting and any still-usable electronic equipment including the chart plotter. But thanks to a trusty engine battery, they could start the motor to bring the ship's batteries back up to short-lived strength. Yet while approaching the Blaskets, the engine refused to start, and nothing they could do would coax it back to life. Inevitably they lost power, and for the final 495 miles of the race – the equivalent of 78% of a Fastnet Race - the boat was sailed and navigated entirely manually, with the required navigation lights provided by modified helmet lamps.

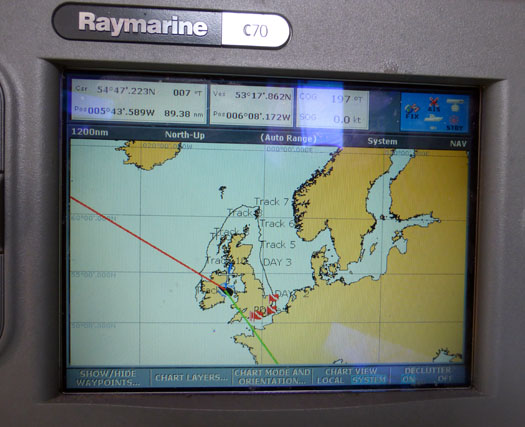

The chart plotter shows only too clearly where power was lost completely just north of the Blaskets. Photo: W M Nixon

Yet they finished well last Saturday, around noon on August 23rd after twelve days racing. They won the two-handed division overall, they won Classes IV & V, and they placed sixth overall in a combined fleet in which big boats with a strong element of professional crewing dominated. So who are Liam Coyne and Brian Flahive, and what about Lula Belle, the heroine of the tale?

Afloat.ie caught up with them on Thursday morning in Dun Laoghaire marina, where they'd got home an hour or so before dawn to grab a quick sleep of a few precious hours before awakening to more sunshine than they'd experienced for a long time, as the Round Britain & Ireland was raced across an astonishingly sunless sea. As for the 450-mile passage home to Dublin Bay, it had been achieved through mostly miserable weather and an enforced and brief stop in Plymouth to try to get a final solution to the continuing electric problems, which had defeated the finest minds in Cowes.

But such hassle fades when the return home is completed, and the Lula Belle crew were in great form. They complement each other. Brian Flahive is from Wicklow and he's a studious, thoughtful type. He turned 31 just three days after the win, making it his best birthday ever, and a fitting highlight in a sailing CV which continues to develop, and began with local sailing and training courses with Wicklow Sailing Club after his sister Carol had acquired a Mirror dinghy.

Since then, Carol's seagoing has taken a slightly unexpected turn as she found her vocation in the lifeboat service, and that is now her main interest afloat - she is a helm on the Wicklow lifeboat. But her younger brother Brian was soon hooked on pure sailing, and from the Mirror he soon went on the 420s where his enthusiasm was noted by local keelboat owners, who in turn recruited him aboard, and soon he was noted by those assembling offshore racing crews too.

When you've talent, enthusiasm and time available, the word soon gets about in the limited recruiting pool available to Ireland's offshore racing folk. Soon, young Flahive was spreading his wings with his home port's biennial Round Ireland race, and participation in Irish Sea Offshore Racing. He proved adept at and interested in two-handed sailing in particular, and soon got to know another relative newcomer to the Irish Sea offshore racing scene, Liam Coyne.

Liam Coyne is 47, and something of a force of nature. There's a mischievous twinkle to his eye, but there's a very serious side to him too, even if – as when he admits he's extremely competitive – it's done in the best of humour. He's from Swinford in County Mayo, where any knowledge of boating might relate to the big lake of Lough Conn nearby. But as he left Mayo for the USA just as he was turning 20, his passionate sailing involvement has been entirely generated during his more recent life in Dublin.

There's a mischievous twinkle, but Liam Coyne makes no secret of his competitive nature. Photo: W M Nixon

Back in the 1980s, well before Australia took off as the destination of choice for energetic and ambitious young Irish people, America was still the Land of Dreams. Coyne's teacher of English in Mayo was so sure of this that one of his courses was built entirely around the USA's immigration examination. He did a good job, young Coyne made the break, and he started to fulfill his ambition of getting to all the American states by spending time – sometimes quite a lot of it – in 26 of the States of the Union. Eventually with a winter approaching, he found the building site he was quietly working on in Boston was due to close completely for the colder months. But he managed to swing a job selling Firestone tyres (sorry, "tires") from the local agent's shops. It was a union created in heaven. Liam Coyne and tyres – the bigger the better – were made for each other.

He prospered in the tyre business in Boston and enjoyed his work, but there was always the call of home and a girl from Swinford who had qualified as a teacher. So he came back to Ireland in 1998, set up in the tyre business in Leinster, married the girl and settled down in south Dublin to raise a family.

Came the boom years, and the tyre business prospered mightily. Liam Coyne Tyres had five depots and employed 48 people. He was mighty busy, but seeking relaxation. So on the October Bank Holiday Monday in 2005, he and his wife went to the Used Boat Show at Malahide Marina and by the time they left, Alan Corr of BJ Marine had sold them a handy little Beneteau First 211, their first boat.

His knowledge of boats and sailing was rudimentary to non-existent. His maiden voyage, the short hop of 12 miles from Malahide to his recently-joined new base at Poolbeg Y& BC in Dublin port, took all of 14 hours as the tyro skipper battled with the peculiarities of tide and headwinds, happily ignoring the potential of the little outboard engine on the transom even though, as Alan Corr cheerfully told him later, it could have pushed the boat all the way to Arklow in half the time.

But he was enchanted by this strange new world, and the camaraderie of the sailing community as expressed in Poolbeg. He made a tentative foray into the club's Wednesday night racing, and was even more strongly hooked. But even though those Wednesday club races in the inner reaches of Dublin Bay were such fun that from time to time he still returns to race with his old clubmates at Poolbeg, he knew that his ambitions would dictate a move into a larger boat, and the bigger world of Dublin Bay sailing. So when the next Dublin Boat Show came along, he went to it and ended up buying a Bavaria 30 from Paddy Boyd, who was marketing Bavarias in the interval between being Secretary General of the Irish Sailing Association, and Executive Director of Sail Canada.

Paddy Boyd wised him up to the Dun Laoghaire sailing scene, and which club he might find the most congenial while being suited to his ambitions. For Liam Coyne was discovering offshore racing, and particularly the annual programme of the Irish Sea Offshore Racing Association. He liked everything about ISORA, the friendships, the willingness to help and encourage newcomers, and the pleasant sense of a mildly international flavour between the English, Welsh and Irish contingents.

One of his fondest memories is of taking his Bavaria 30 across to North Wales for the annual Pwllheli-Howth race which traditionally rounds out the season, and is often blessed with Indian summer weather. As he headed away from Dublin Bay, he suddenly realised it was the first time he had ever left Ireland under his own command. All previous exits had been on scheduled ships or planes. It was a very special moment.

Yet while he treasures the memory of such special moments, it wouldn't be Liam Coyne if he wasn't moving on. He'd relocated his base of operations to the bigger scene of the National Yacht Club and Dun Laoghaire, and developed his taste for double-handed offshore racing and its link to a group whose only common denominator seemed to be that many of them shared an enthusiasm for racing vintage Fireballs in Dun Laoghaire harbour in the winter.

But in the summer, keelboat offshore racing with just two on board was increasingly their main line, and he was soon on terms of friendship with the likes of Brian Flahive, Barry Hurley and others, while the double-handed class in events like the Dun Laoghaire-Dingle, the Round Ireland, and the Fastnet itself were coming up on the radar.

The newly-acquired First 36.7 which became Lula Belle greatly broadened the scope of Liam Coyne's offshore racing. Photo: W M Nixon

The First 36.7 is of a useful size to be a very pleasant family cruiser, but Lula Belle has been a multi-purpose boat since Liam Coyne bought her, with the emphasis on double-handed offshore racing, and the longer the course, the better. Photo: W M Nixon

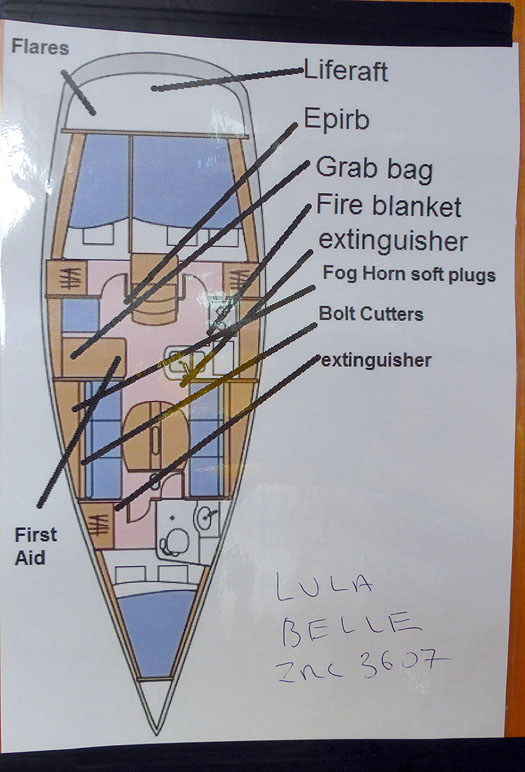

Lula Belle's layout - the accommodation of a cruiser/racer with extras installed for serious offshore racing, but for proper cruising they'd also be required. Photo: W M Nixon

Having made his mark offshore partnered with Brian Flahive on the Bavaria, he very quickly moved up to the almost-new First 36.7 Baily, bought from Tom Fitzpatrick of Howth. His name of Lula Belle for the boat was inspired by a recently-deceased aunt who had invariably addressed all of his sisters as "Lula Belle" when requesting something like a cup of tea. It's certainly a distinctive name, and it was beginning to feature regularly in short-handed and fully-crewed offshore racing reports when Ireland fell off the economic cliff around 2007.

The tyre business was hit particularly hard, for they're items whose replacement people can try to avoid by shifting used tyres around on and between vehicles to get the last piece of tread usable. But fortunately, one of his key contracts was in the heavy industrial area, where they use tyres so big your everyday motorist has no notion of them, yet legal safety working requirements dictate their regular replacement.

Despite this, at one stage his fine workforce of 48 had become effectively just two, while three of the five depots were closed. "I can tell you" he says, "there were times when we were glad enough the wife had kept her teaching job". And they were raising a family, eventually with three kids with a much-loved holiday home at Enniscrone in southwest Sligo. Then too he had this 36ft racing boat too. Yet all his fine assets and the value of the family home in Dublin had effectively been slashed by at least 50% and often more.

But somehow he kept going, and he even continued to race offshore. By this time one of the leading figures in the Irish short-handed sailing scene, Barry Hurley, had moved to Malta, and when he was recruiting crew for a friend with a Grand Soleil 40 for the annual 620-miles Middle Sea Race from Valetta in late October, he filled four berths with able-bodied crew from Dublin including Barry Flahive and Liam Coyne.

That race brought something of another epiphany to match that moment of pure joy at realizing he was skippering his own boat out of Irish waters for the first time. They'd come through the Straits of Messina eastward of Sicily, and next turn of the course was the volcanic island of Stromboli. It was a blissfully warm summer's night, and Liam was at the helm in just shorts and shirt, enjoying the sail and revelling in the race.

Stormboli was gently erupting just enough to show it was there, and ideal to be a mark of the course. "I'll tell you," says Liam, "it was a very long way indeed from your usual October night in Swinford". The magic of the moment reinforced his ambition to see his business through the recession and out the other side, which he has now achieved with busy depots in Navan and Dublin, and staff back above the twenty mark. Yet oddly enough, it also reinforced a shared ambition with Brian Flahive to do the four-yearly Seven Stars Round Britain & Ireland Race, when conditions up in the northern seas off Shetland and across towards the Faroes can often make an October night in Swinford seem like the balmy Mediterranean by comparison.

But the idea just wouldn't go away, and they put down their names for the 2014 race. With the economy coming out of intensive care and two good managers running his two depots and the three kids though the very young stage, Liam Coyne felt he could take off the time for this major challenge. But even so it was done without any form of shore management support, and in fact he managed to mix it with some family cruising – to which the boat is surprisingly well suited – by taking his young son Billy (10) and daughter Katie (8) along with him for a leisurely delivery to Cowes by way of many of the choice and picturesque ports along the south coast of England, where his wife and the youngest child joined the party to see them off.

That was in the last of the summer. By the time the starting date was upon them, it was as if a giant and malevolent switch had been activated. The weather was horrible, and even when Bertha had finally grumbled along on her way, it was anticipated that the rush of bitterly cold north winds she'd drag down from the Arctic in her wake would be every bit as unpleasant.

Then came the complete reversal of the course, and the postponement of the start. For a crew who were being their own shore managers and technical support team, it added a last minute mountain of research work on the shape the weather might be when they finally got away, and all the mental strains of waiting overnight for the start. As the lowest-rated boat in the entire fleet, they may have had the consolation of knowing that if they finished with just one boat behind them then they wouldn't be last on corrected time. But by being the low-rater, they would probably finish so long after everyone else that any general celebration would be long over.

That said, when a double-handed team have already successfully bonded, they're better at withstanding the strain of an enforced wait for a delayed start than a larger crew. I can remember only too well when the RORC Cowes to Cork race of 1974 was postponed for ten hours by the then RORC Secretary Mary Pera. A Force 10 sou'wester was making the Needles Channel a complete maelstrom on the spring ebb, but it was forecast soon to ease, so we were to be sent off on the evening ebb.

To get through the wait, it seemed best to stay well away from the boat and have a quiet day if at all possible. But aboard the 47-footer on which I was sailing, there were action men who decided it was time for a party lunch. So although I slunk away alone up the back streets of Cowes (Kensington-on-Sea it was not), and found a little café where the owners were persuaded to provide lunch of boiled potatoes and steamed fish instead of the usual nausea-inducing fish'n'chips, back on the waterfront others meanwhile had different ideas. A massive former rugby international in our crew decided the best way to pass the time was a champagne reception in one of the Cowes clubs followed by a bibulous lunch, and he persuaded several shipmates to join him, though they were circumspect in their consumption while he went at it as though it would be the last festive lunch in his life.

When we finally got racing the wind had indeed eased, though things were still rough enough in the Needles Channel, where we slammed into a head sea with such vigour that the Brookes & Gatehouse speedo impellor – normally a particularly stiff-to-move bit of equipment – was shot into its hull housing so totally we assumed it had broken entirely. It took a few seconds to realize what had happened, and it worked again happily enough once it had been pushed back into working position with the usual robust heave.

However, our mighty rugby forward was not so happy. He was not a happy budgie at all. The news is that, though you may be battering along noisily but successfully with endless bangs and squeaks and groans of one sort or another, when an international rugby forward of classic size gets massively seasick, a new dimension enters the sound and vibration scene - it's as if the entire boat is shuddering from end to end.

But enough of that. In Cowes on the morning of Monday August 11th 2014, it was still blowing old boots from the west , but they tore away downwind like there was no tomorrow. And for some, as far as racing was concerned, there wasn't. Any tomorrow, that is. There were several overnight retrials that set out to be temporary but became permanent. Aboard Lula Belle, however, they were still going strong, but after recording that gust from astern of 42.5 knots (which meant it was pushing 50), the masthead broccoli decided it had had enough, and made its exit.

Some time long before the race, Liam had decided he'd ensure the minimum use of power by having a LED tricolour masthead light, and a technician had been sent aloft to fit it. But that first night, it took off on its own, but taking much else with it, and leaving a beautifully clean masthead, but damn all information for those down below other than a Windex with an increasing tendency to jam.

And already the sails were suffering, for although their gybes were hectic enough, they didn't have to worry about check-stays or runners. But the downside of that was the well-raked spreaders, which helped support the mast in the absence of any aft support rigging other than the standing backstay. The inevitably prominent upper spreader-ends were chafing holes in the mainsail which, despite repairs, were enormous by the finish.

Speed at sea – Brian Flahive on the wheel as Lula Belle puts in the kind of sailing which knocked off 200 miles a day. Photo: Liam Coyne

But they blasted on, roaring on a reach up through the North Sea with Lula Belle doing mighty well, as the more extreme boats such as their closest rival, the Figaro II Rare, weren't quite getting the conditions to enable them to fly, whereas old Lula Belle was knocking off 200 miles in every 24 and saving her time very nicely.

North of the English/Scottish border, the strong winds drew ahead. The forecast, however, was for westerlies, so some boats in front laid markedly to the westward looking for them. But Coyne and Flahive sailed a canny race. What they knew of the weather maps suggested very slow-moving and messy weather systems with lots of wind. And from ahead. They reckoned the prospect of westerlies was just too good to be true. And they were right. On the entire leg up to Muckle Flugga, the most northerly turn, they never strayed more than five or six miles from the rhumb line, and thus they sailed the absolute minimum distance, albeit in very anti-social conditions, to get to the big turn.

The sunless sea, with Lula Belle getting past Muckle Flugga on Shetland, the northerly turning point of the RB & I Race, and the sky promising plenty of wind Photo: Liam Coyne

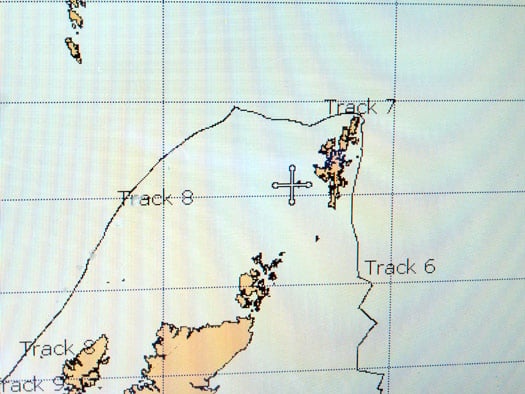

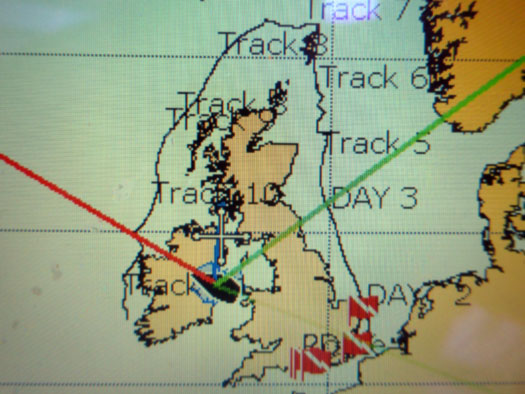

The win move. Although Lula Belle had taken a conservative route northward, once they'd rounded Muckle Flugga they took a flyer to try to get on the favoured side of a slow-moving yet very intense low. The plan succeeded, but they'd to go almost halfway to the Faroes for it to work. Photo: W M Nixon

By this time the faster boats had got back into a substantial lead, but here the situation suited the Irish duo. Those in front went battering and tacking into a fierce sou'wester, trying to get nearer the next turn at St Kilda. But the Irish boat's cunning scheme was to slug directly westward once they'd rounded Muckle Flugga, and not tack until they'd some real prospect of being in the harsh northerlies which they knew to be somewhere out beyond the very slow-moving low pressure area.

Thus they ended up midway between the Shetlands and Orkney to the southeast, and the Faroes to the northwest. As Liam Coyne drily puts it: "When you take a flyer like this and it works, it isn't a flyer any more – on the contrary, it's the only way". What they didn't know was that the boats trying to batter their way past the Outer Hebrides and down towards St Kilda had taken such a pasting that their immediate rival Rare had made a pit stop to rest up in the Shetlands, and others dropped out "for a while" only to find it had become a matter of retiring from the race.

But Lula Belle, having cast the dice to go west, had no option but to keep going, as she was nearly 50 miles west of the Rhumb Line, and more a day's fast sailing from any shelter. By this time, the Scottish forecasters had up-graded their gale warnings to severe storm Force 10. But thanks to their pluck in going west, Coyne and Flahive were up towards the northwest corner of the low, whereas the opposition were down in the southeast quadrant where the winds are usually significantly stronger.

Nevertheless at the change of the watch they shortened sail to the three-reefed main and the storm jib, even though the wind had fallen right away. Brian went off watch and then returned on deck after some sleep to find Liam had become becalmed, and had been so for some time. The centre of the low was passing straight over them. Now it was only a matter of time before the new wind came out of the north.

When it did it was nasty and cold, and the sea became diabolically rough and confused. But it was a fair wind, and they made on as best they could through the short northern night to close in on St Kilda. It was sunrise when they went past that lonely sentinel, and for once there was briefly sunshine to prove it, but it was watery bad weather sunshine as they settled in for the long haul to Ireland.

A great fair wind at last, but it was so very very cold despite some sunshine. Photo: Liam Coyne

Early morning as they pass St Kilda, with Lula Belle well placed in the race and her closest but higher-rated rivals astern. Photo: Iiam Coyne

By this stage the boat was very much their home, and they were both in good spirits. Despite the expectation of being in race mode for at least ten days and probably much more, they hadn't anything too much in the way of special easy-made instant food. When asked who had organized their stores and how they had been procured, Liam responded: "I just went to Tesco before the race, and filled her up. It's very easy when you've only two. I've had to do the stores for the boat with a crew of eight, and it's a pain in the neck".

Getting an omelette just right is tricky at the best of times, yet this masterpiece was created aboard Lula Belle off the coast of Donegal in 30 knots of wind. Photo: Liam Coyne

As for living aboard, they used the two aft cabins for sleeping, with hot bunking dictated by which was the weather side. In cruising mode, the First 36.7 is a very comfortable boat, but in racing things tend to get put behind the lee-cloth on the weather settee berth in the saloon, for the fact is the boat is designed to be raced with a crew of 7 or 8, and she tends to be a bit tender without six bodies on the weather rail.

Post-return temporary disorder in Lula Belle's saloon on her arrival back in Dun Laoghaire after sailing nearly 3000 miles in all since she'd last been in her home port. Though Brian (left) and Liam used the aft cabins for the short off-watch periods of sleep, the lee cloths on the settee berths were kept up to provide ready stowage for loose gear, preferably on the weather side. Photo: W M Nixon

Having the toilet on the fore-and-aft axis is very convenient at sea. And having an "extra-easy-cleaned" compartment is a real boon for hygienc. As for the funnel and hose, that's essential in a men-only boat in racing mode. Photo: W M Nixon

To my mind, one of the best things about the accommodation is the heads (toilet if you prefer). Some folk might think the compartment is too compact, but the loo is aligned fore and aft, so there simply isn't the room to fall about when using it. With the fore and aft alignment, security and comfort is guaranteed at those special private moments. It should be a law of yacht design that any boat which is going to be taken further than half a mile offshore is designed with a fore and aft loo.

Such thoughts would not have been forefront in the minds of Lula Belle's crew as they set the A3 spinnaker for the long run to Black Rock off the Mayo coast. Inexplicably, and as evidence of their stretched shoreside management support arrangements, they'd failed to bring along a new Code Zero spinnaker from sailmaker Des McWilliam. They'd gone for it despite it putting three extra notches on their rating, but it was nowhere to be found. After the race, it was discovered among a pile of 20 sails in Liam's Dublin office. But out in the lonely ocean southwest of St Kilda, it wasn't there when it was needed.

Yet it was soon needed even more. The smaller sail that was put up simply disintegrated after a brief period of use. It was inexplicable, but reasons weren't important just then, they were now down to just two spinnakers, and a very long way to go downwind to the finish.

So they nervously got out the A4, and soon it was up and drawing and Lula Belle was back in business, sailing fast for Ireland. Liam went below for a much-needed kip, and a sudden squall over-powered the boat. By the time he got back on deck she'd broached completely and the sail was shredded. They were down to just one spinnaker, and one in very dodgy condition at that. To add to their joys, in a crash gybe the mainsheet carriage disintegrated and they'd "ball bearings, it seemed like hundreds of them, all over the place...."

So there they'd been, passing St Kilda and knowing that, despite the lack of sailing instruments, they couldn't have done the leg from Shetland any better, and more importantly knowing from Yellowbrick that Rare was now well astern. Yet here they were now, only a few hours on the way, and they were down to one spinnaker and a jury-rigged mainsheet arrangement and a long way to go and the weather starting to suit Rare. Could it get any worse?

It did. Approaching the Blaskets, as usual the ship's batteries were draining with unreasonable speed. But the engine, when called upon, was dead. Dead as a dodo. It turned over but just wouldn't start. They knew that in very short order they'd be even further cut off from the outside world than they were already, with no chart plotter and without even the comfort of Yellowbrick to tell them how they stood in relation to the opposition. No autohelm whatever, either. And they'd 495 miles still to sail.

Moment of truth. The chart plotter's power dies just north of the Blaskets, the most westerly point of the 1802-mile course. Photo: W M Nixon

Getting on with it. Just south of the Blaskets, Brian goes aloft to try and clear the constantly-jamming Windex. Photo: W M Nixon

So they picked themeselves up, dusted themselves off, and started all over again. Brian went aloft to the waving masthead to free the Windex, which was in its jamming mood. Then progress was good heading down towards the Isle of Scilly. But even so, midway across, alone at the helm and steering and steering and steering, Liam admits to a very low moment.

They were now almost midway between Cowes and Dun Laoghaire, So he thought to himself: Why not just turn to port and head for home? Head for that comfortable NG34 berth in Dun Laoghaire marina, instead of struggling on with sails which were bound to shred even further, and leave them eventually straggling across the line completely dog last and with everything to fix, and then they'd have to turn round and plug into the early Autumn gales all the way back round Land's End to Dun Laoghaire?

And what then? he thought. Well, then in four years times we'll have to do the damned thing all over again. All, all, over again. So we'll just finish the bloody thing now, and get the T-Shirt, and that will be that regardless of how far we're placed behind everyone else, and good riddance to it all.

Welcome back. Knowing of Lula Belle's engine-less plight, the Cowes harbourmaster made sure they were brought into their Berth of Honour in style. Photo: Liam Coyne

So they stuck at it, they nursed the boat through the shipping separation zones at the Scillies without the spinnaker up because they knew the multiple gybing would destroy it, then as Rare didn't get past them until this stage, they knew that after such a long race she'd need to be 22 hours ahead at the finish and that was surely impossible. They were very much in with a shout of being better than last, so they nursed that mangled old spinnaker right up the English Channel (Mother Flahive's emergency sewing machine had done some marvellous repairs), and maybe the spreader ends were now showing out through the mainsail again, but what the hell, they got in round St Catherine's point and shaped their way back into the eastern Solent and on up to Cowes, and didn't Rare's crew and various bigwigs come out to tow them into port and confirm to them that they had indeed been there, they'd seen it, they'd done it, they'd won it., and now they could get the T-shirt.

Been there, seen it, done it, won it, got the T-shirt.....Liam Coyne back at the bar of the National YC five days after winning the two-handed division and two RORC classes in the 1802-mile Seven Stars Round Britain & Ireland Race 2014, and with his boat Lula Belle safely returned to her home port of Dun Laoghaire. Photo: W M Nixon

Ireland's Oldest Wooden Boats Aren't Getting Any Younger

#woodenboats – On Midsummer's Day, W M Nixon looks back on the already busy and event-filled Irish season of 2014, and reflects on the extraordinary longevity of some boats, their remarkable variety, and the diverse characters who own them.

When I shipped aboard the former Bristol Channel Pilot cutter Madcap to sail the Old Gaffers Division in Howth Yacht Club's Lambay Race on June 7th, it wasn't the first time I'd been out and about on a boat built in the 1870s. But as most of my experiences on John and Sandra Lefroy's 1873-vintage iron-built classic 58ft Victorian steam yacht Phoenix on Lough Derg took place in the 1970s with the most recent jaunt being way back in 1982, sailing on the Madcap was indeed the first time afloat in a boat built 140 years ago.

It takes an effort to get your head around the most basic notion of such an age. You find yourself reflecting on the delights that still awaited the human race at the time, things that were still far into the remote future in the 20th Century. During the 1870s, industrialisation was still gaining traction, but the very idea of warfare on the industrial scale which was to be experienced in the Great War of 1914-18 was beyond most people's imagination, and way beyond anyone's experience. That said, there were more than enough other ways of experiencing an early death, with a range of particularly unpleasant illnesses which have been largely eliminated today.

Yet it was increasing industrialisation which created the circumstances that enabled both boats to be built. The Bristol Channel Pilot cutters evolved rapidly in the latter half of the 19th Century in order to provide pilots for the more numerous and increasingly large ships which were coming into ports such as Cardiff and Bristol. They reached their peak of performance around 1900, by which time they'd achieved a remarkable stage of development, being fast and able, yet comfortable at sea, and capable of being handled by a very small crew after the pilots had been delivered to incoming vessels. When their working days were over as they were replaced by motorised vessels, they proved ideal as seagoing cruising yachts.

There was nothing work-oriented about the pleasure yacht Phoenix when she was built to the designs of Andrew Horn in Waterford in 1873. Or maybe that's being a bit naïve. After all, she is down as having been built by and for the Malcolmsons of Waterford. They were a remarkable clan who brought many industries to Waterford in the 19th Century, and they created the miniature industrial town of Portlaw westward from the city, off the south bank of the Suir Estuary.

The 58ft Phoenix, iron-built in Waterford in 1873, performing Committee Boat duties at Dromineer for Lough Derg YC. Photo: Gerardine Wisdom

So in building the Phoenix themselves, so to speak, they were creating a subtle advertisement for Waterford expertise, with this new miniature of an ocean liner being constructed in the highly-regarded Lowmoor iron. And she's a powerful statement - this lovely old vessel has lasted much better than many of the Waterford enterprises which outshone her at the time of her building, so much so that if, in Waterford's current recessional woes, they sought something to symbolise what the city is capable of, they would do worse than put some resources the way of the Phoenix for her continuous maintenance.

Five years ago she made a very stylish appearance as the Committee Boat in a classics regatta at Dromineer, and that in turn produced an astonishing photo which included Ian Malcolm's 1898-built Howth 17 Aura. It was the first time a jackyard topsail had been seen on Lough Derg since before the Great War, and all that together with a raft of Shannon One Designs (which date from 1922 onwards) and a fleet of Dublin Bay Water Wags from 1902 onwards meant that the total age of the boat in the photo was pushing towards the 2,000 years mark.

Phoenix and the 1898 Howth 17 Aura (Ian Malcolm) at Dromineer with rafts of Shannon ODs and Water Wags. The combined age of the bots in the photo is well over a thousand years. Photo: Gerardine Wisdom

To be aboard Phoenix is to be transported right back to the 1870s, as she has a beam of only 10.5ft, which on a length of 58.5ft make for one very slim and potent hull. She has long since had her original steam engine replaced with a diesel, and back in 1982 when I was last afloat in her, it was October, and we were the Committee Boat for the annual IYA Helmsmans Championship, raced that year in Shannon One Designs with Dave Cummins of Sutton the winner, crewed by Gordon Maguire.

Being late season, the Phoenix's injectors needed a clean, but as the Race Officers were those perpetual schoolboys Jock Smith and Sam Dix of Malahide, they were delighted by the Phoenix's ability to emit a fine plume of smoke from her funnel at full speed, and after the championship was resolved they tore across the lively waters of Autumnal Lough Derg at full speed while – from another boat - I grabbed some photos which made Phoenix look like a destroyer in action at the Battle of Jutland. One of them subsequently appeared as the cover of Motor Boat & Yachting, and as I seem to have mislaid the colour slides, if anyone has a copy of that particular edition I'd much appreciate a scan of it.

Moving on from the 1873-built Phoenix in 1982 to the 1874-built Madcap in 2014 is quite some saga, but we'll edit it by sticking to events this year revolving around the developing annual Old Gaffer programme in the Irish Sea. Last year Dickie Gomes' 1912-built 36ft John B Kearney yawl Ainmara from Strangford Lough won the inaugural Leinster Trophy race in Dublin Bay which marked the OGA's Golden Jubilee, and she did it despite now being bermuda rigged. But as she was returning to her birthplace in Ringsend for the first time in 90 years, she was treated as an honorary gaffer.

Honour being the theme of things, this meant we were honour-bound to bring her south again to defend the Leinster in 2014, but this was given an added impetus by a plan to link up in Dun Laoghaire with Martin Birch's 1902-built Espanola out of Preston in Lancashire. From 1912 until 1940, the 47ft Espanola was a feature of the Royal Irish YC in Dun Laoghaire, owned by noted sailor Herbert Wright, who in 1929 became the founding Commodore of the Irish Cruising Club when he cruised Espanola with four other yachts to Glengarriff where the ICC was founded on July 13th 1929. The Espanola links, together with the fact that the RIYC is now in partnership with Wicklow Sailing Club in hosting the fleet for the biennial Round Ireland Race, made for a fortuitous combination, as Dickie Gomes of Ainmara was Mr Round Ireland between 1986 and 1993, when he held the open Round Ireland Record and also had been overall winner of the 1988 race.

Espanola as she was in 1929, when Commodore's yacht at the founding of the Irish Cruising Club

The 1902-built Espanola as she is today

Thus all the stars were in alignment for an historic and convivial meeting of the two old boats at the RIYC on the evening of Friday May 30th, the night before the Leinster Plate race was due to start just round the corner in Scotsmans Bay. But while stars may have been in alignment, ducks failed to get into a row, as Espanola with her exceptional draft of 7ft 6ins failed to get out of Preston over the shallow bar in the one tide which would have suited, on May 16th.

This situation is a useful illustration of the problems the old gaffer people face in keeping the show on the road with limited resources. Martin Birch, having been a lecturer in Lancaster University, had found Preston's little marina an ideal place to keep and maintain Espanola, and the marina in turn regarded the old girl as their pet boat. But Preston is longer a busy commercial port, so the channel has been left to is own devices, and with the huge tides of the Lancashire coast, getting Espanola to sea is quite a challenge as sometimes there's only one day in any month when it can be done.

So there we were, faced with the prospect of Hamlet without the Prince with just ten days to go to the historic gathering at the RIYC. But Jim Horan, affable Commodore of the Royal Irish YC, took it all in his stride and told us to bring Ainmara along anyway, it would be a good excuse for a Friday night party and he was keen to meet the skipper who had made the Round Ireland challenge very much his own 28 years ago.

Jim Horan, Commodore of the RIYC, told us to come on and be welcome even though Espanola couldn't make it. Photo: W M Nixon

With the foul weather of mid-May, while Ainmara had got afloat from her winter quarters in a hayshed at the Gomes farm on the Ards peninsula in County Down, further fitting out was difficult in endless rain, and the skipper came down with a massive cold. But then the weather perked up, and he did too, so at lunchtime on Thursday My 29th we headed down Strangford Lough from the Down Cruising Club's former lightship headquarters at Ballydorn to catch the start of the ebb in Strangford Narrows at 1430 hrs.

Progress was good with a light to moderate nor'easter, but Ainmara and her crew (there were four of us – Brian Law, Ed Wheeler and I together with Dickie) have got to the stage where nights at sea are regarded to be the result of bad cruise planning. Yet if we were going to be comfortably in Dun Laoghaire for Friday evening, then only Port Oriel at Clogherhead made sense as an overnight. But Port Oriel, home to some of the best-maintained fishing boats on the coast, can become a very crowded place on a Thursday night.

However, a phone call to the uncrowned king of Clogherhead Aidan Sharkey – whom I'd first met back in the 1980s when our two boats were moored in Seal Hole at Lambay, where he was diving on the nearby 1854 wreck of the Tayleur - ensured there'd be a berth for us, and when we arrived in at sunset there was the man himself to direct us to a corner where we wouldn't inconvenience fishing boats, and moreover had access to a set of proper steps.

Port Oriel at Clogherhead provided Ainmara wih a handy overnight stop. There was more space available (below) as most of the 30-strong local fleet were away fishing the south coast. Photos: W M Nixon

Aidan's commitment to the maritime life is total. He's of an old Clogherhead fishing family, and he and his late brother Feargal were the backbone of the local beach-launched lifeboat crew. The banter was mighty on board Ainmara, leavened with tales of lifeboat experience which would curl your hair. The laughter through the companionway attracted others board, and soon Sean the razor clam man (all of his catches go straight to China) was in the hatchway with glass in hand, and when we asked where we might get a new deck scrub first thing in the morning as somehow the ship's own one had gone AWOL, Sean said not to worry, he'd throw one on board, and we could just leave it on the big fishing boat beside us as we left next day.

Ashore, I went up to Aidan's house in the village as he'd said he'd something to show me, which was an understatement. He was into the diving much earlier than most, thus when he got to wrecks which today are known to everyone, there were still intact bits of the cargo to be salvaged. Most east coast divers have fragments of chinaware, pottery and other artefacts from the Tayleur, but Sean had so many complete pieces, together with many other items of special antique value from other wrecks mostly in Donegal, that he would be well able to provide complete afternoon tea for the entire choir, all served on 1840s china. But it wasn't tea I got in the Sharkey household, it was Aidan's present of a large bag of fresh crab claws, and a selection of his own-cured salmon – smoked and gravid lax both – which sustained us through the next day's sail.

Aidan Sharkey of Clogherhead with some of his remarkable collection of salvaged chinaware. Photo: W M Nixon

The sort of sailing cruising folk dream of. Ainmara shaping up nicely to take the first of the fair tide through the islands at Skerries. Photo: W M Nixon

The morning brought the welcome gift of a decent little sunny east to nor'east breeze, and a lovely beam reach all the way down to Dublin Bay, with the south-going tide caught to perfection at the Skerries islands (and yes, I know it's superfluous to talk of the "Skerries islands", but that's what they're called to differentiate them from the Skerries off Holyhead).

Anyone who was involved in last weekend's ICRA Nationals at the Royal Irish YC will know how this premier club can lay on the welcome with effortless style. In the last weekend of May, Ainmara and her crew had the Royal Irish treatment all to themselves. Sailing Manager Mark McGibney ushered us to the prime berth right at the club where we found ourselves in a miniature maritime museum, with the Quarter Tonner Quest close astern (she was to become the ICRA National Champion a fortnight later), while just across the way was the S&S 36 Sarnia – back in 1966, the Sisk family set Irish sailing alight by bringing this very up-to-the-minute fin-and-skeg fibreglass boat back from builders Cantiere Benello in Italy, where they'd started series production on this ground-breaking Olin Stephens design before the same hull shape became better known as the Swan 36 built by Nautor in Finland.

"Maritime museum" at the Royal Irish YC. Ainmara (built Ringsend 1912) with the 1987 Quarter Tonner Quest astern, and the 1966-built S&S 36 Sarnia across the way in her marina berth. Photo: W M Nixon

It has to be one of the best berths in the world. Ainmara at the RIYC – it's early morning, and the flags aren't yet hoisted. Photo: W M Nixon

The hospitality flowed seamlessly as the late afternoon graduated into evening and then velvet night. Ainmara is an extraordinarily effective calling card, and the stream of entertaining visitors brought laughter aboard before the Commodore moved us all up to the clubhouse and a fine supper and much chat with Michael O'Leary, one of the most visionary minds in Irish sailing, and his wife Kate and her people with tales of how she and longtime friend Clare Hogan are in the thick of things in the very healthy Water Wag class.

The RIYC took all this in its stride despite the fact that there was a big wedding going in the clubhouse at the same time, but it all went so smoothly that at one stage Ainmara's crew found themselves being invited to join in the wedding celebrations. However, we demurred because we were athletes in training for the Leinster Trophy next day, yet nevertheless certain key players in the wedding got themselves aboard Ainmara at a very late hour.

The plan for Saturday had been changed, but we were right up to speed with this as Denis Aylmer, the RIYC's key man in the OGA, had told us over a convivial pint that the likelihood of light winds had meant that Race Officer John Alvey had moved the scene of the action from Scotsmans Bay to a more compact race area close off the entrance to Dublin Port. It was all grist to our mill, as we could make an early morning departure and head up to Poolbeg Y & BC across a mirror-like bay, lining up the crew to salute the North Bank Lighthouse in the River Liffey, as it's something of a memorial to John B Kearney, whose day job was in the engineering department in Dublin Port and docks. With his original lighthouse, he pioneering a technique of screwing the piles into the seabed. You'd have thought an air of reverence would prevail, but with Ainmara's crew of anarchists, straight faces could only be maintained for about 12 seconds.

Trying to look appropriately reverential. Ed Wheeler, Brian Law and Dickie Gomes approaching Dublin Port's North Bank Lighthouse on which John B Kearney pioneered the use of screw piles. Photo: W M Nixon

"We're only here for the breakfast". Katy O'Connor's excellent catering in Poolbeg Y & BC is deservedly popular among visiting crews. Photo: W M Nixon

While we wanted to be well on time for the pre-race briefing, the main reason for getting promptly to Poolbeg was to take full advantage of Katy O'Connor's legendary breakfast at the club, and we put away enough calories to keep us going all day. At the briefing, John Alvey told us the committee were concerned that the very varied fleet – everything from Ainmara to the big Naomh Cronan, a superb Clondalkin-built re-creation of a Galway Hooker – included some boats which, in the light airs expected, could be out on the bay until nightfall.

So the plan was for a short race taking in several marks so that it could be finished at the end of any leg. But by the time we got down to Dublin Bay, it was crisp blue with a smart little sea breeze filling in to give sailing conditions which suited Ainmara to perfection, yet some of the heavier gaffers were still lumbering slowly about in what to them was a light wind.

They may have been lumbering about, but several were very determined to make a sharp start right on the committee boat. Anyone accustomed to quick-turning and fast-accelerating modern boats will find a fleet of traditional and classic gaffers a real education. They take time to get moving, they take for ever to stop, you point them a long way out, and their bowsprits – "dock probes" as marina managers call them – seem intent on skewering everyone else.

But while our skipper may pretend to be just an old cruising man these days, his racing blood was up. We set ourselves to sweep into what we hoped would be a gap starting to appear at the committee boat seconds after the start signal. We consoled ourselves with the thought that in extremis, we might just manage to shoot head to wind leaving the committee boat to port, ruining our start perhaps, but preserving the Ainmara intact.

"Go for it, and let's hope there's a gap when we get there..." Ainmara starts to build speed towards her start in the Leinster Trophy Race 2014 . Photo: Gill Mills

So she was set at it, despite attempts to slow her a bit the speed built up, but as quickly as I'm telling this the gap started to appear and she zapped into it and just managed to keep her wind clear on Sean Walsh's remarkably fast Heard 28 Tir na nOg and Denis Aylmer's Mona. Now we had to find the DBSC marks in the right sequence, but Ed was on top of it feeding co-ordinates and giving out courses, we found that with a bit of luck we might just lay the first mark close hauled, and though Tir na nOg – whose waterline length is much the same as Ainmara's – hung in very well, he'd to tack for the mark while we scraped by it, so after that it was up jib tops'l and making hay.

But though we took line honours, we felt certain Tir na nOg would win on corrected time, as a Heard 28 sailed as well as she is can be one very potent performer, and Sean seemd to be still right on our stern at the finish. The results wouldn't be announced until Monday evening, so that Saturday afternoon we wandered back upriver to Poolbeg in sunshine so powerful that an afternoon zizz was your only man, and then we emerged on deck to find that others were arriving in port, with one of the the Welsh visitors, the engine-less Happy Quest from Milford Haven, making a copy-book job of berthing under sail, and then all was alive with the Howth Seventeens arriving in from their home port after a very close-fought passage race which had been narrowly won by Conor Turvey sailing Isobel.

Happy Quest from southwest Wales lives up to her name with a successful berthing under sail only at Poolbeg. Photo: W M Nixon

The Seventeens were there to put on a display race next day (Sunday) in the Liffey as part of the three day Dublin Port Riverfest over the Bank Holiday weekend. Inevitably for those of us who took part in the first one in 2013 when the OGA Golden Jubilee was top of the bill, there wasn't quite the same buzz, but first-timers watching aboard the restaurant ship Cill Airne assured us they found it very exciting indeed, and were especially impressed by the waterborne ballet of the two big harbour tugs Shackleton and Beaufort, while the funfairs and entertainment shows along the quays really did provide something for everything.

Once again the very sight of the Seventeens – which we in Howth tend to take for granted – was fascinating in the city setting. Though the promise of a decent breeze evaporated, Race Officer Harry Gallagher managed to get enough in the way of results to declare Peter Courtney with Oonagh the winner, an appropriate result for an historic class making a show performance, as the Courtneys have been involved with the Howth Seventeens since 1907.

I watched it all from an appropriate setting, aboard the Dutch Tall Ship Morgenster, a handsome 150ft brig which should be required visiting for anyone promoting the idea of a new Tall Ship for Ireland. For the Morgenster – which was re-configured as a sailing ship in 2009 – is run as a commercial venture, and can pay her way through being the right size to be a business proposition, helped by being based in the Netherlands. Thus she has a vast continental catchment area nearby to attract trainees of all ages and abilities who are prepared to pay enough for berths to keep the show efficiently on the road. There are several Dutch-based tall ships run in the same way, and the message is that if you're going to make a go of it commercially, you have to have a large enough and readily-accessed market to make it viable, and you need a boat big enough to carry sufficient trainees relative to the size of the ship – 36 in Morgenster's case – to balance the books.

Tall ships in the Liffey, with the commercially-run 150ft sail training big Morgenster at centre. Photo: W M Nixon

Sails and the city – Howth 17s at the Sam Beckett bridge Photo: W M Nixon

There was just enough wind for the first race for the Howth 17s to show what they could do in the Liffey if the breeze held up. Photo: W M Nixon

The Dublin Port tugs have awesome power to deploy in their waterborne "ballet" Photo: W M Nixon

But enough of solemnity. We went downriver again for farewells at Poolbeg, and then away across Dublin Bay and round the Baily for a seafood feast in Howth at the new place Crabby Jo's, and a handy overnight stop before using a good westerly next morning to give us a push towards Ardglass where we needs must stop, as the tides into Strangford Lough are a door slammed shut every six hours. But as ever, Ardglass's convenient and friendly little marina provided the perfect decompression chamber, and up in Mulherron's the crack was mighty with the crew of the famous restored Manx longliner Master Frank, just the two of them with skipper Joe Pennington - aka The Rat – being crewed by a psychiatrist who claimed to be strictly on holiday, but we did wonder, as any gathering of Old Gaffers is better than a wardful of nutters.

Ainmara's mini-voyage concluded next day with a text message from Dublin to tell us we'd retained the Leinster Trophy, which surprised us, and then with an idyllic sail in a sunny sou'wester, everything set to the jib tops'l, and all sail carried right through The Narrows, across Strangford Lough and thorough Ringhaddy Sound, and on across a blue sea among green islands past tree covered shores until we handed the sails just off the entrance to Down Cruising Club's isle-girt outer anchorage immediately south of Mahee Island, in a little sheltered area which has somehow acquired the unlovely name of Pongo Bay.

Home again. Ainmara back on her mooring in Strangford Lough, with Brian Law's classic yawl Twilight astern. Photo: W M Nixon

There, Ainmara is securely moored close to Brian Law's own cruising boat, the beautifully restored classic Lion Class yawl Twilight, designed by Arthur Robb. Like Dickie Gomes, Brian does all his own boatwork in a hayshed beside the house. So closely intertwined are their interests that they readily crew for each other, and of course the exchange of information and assistance and re-fit ideas is continuous.

And there's one further fact about these guys which may be of interest to other cruising crews. Aboard Ainmara during the three seasons in which I've cruised on her since she was restored for her Centenary in 1912, there's no kitty to cover expenses. There's an underlying feeling that as the skipper provides the boat, the crew owe him on a permanent basis. Thus if we get into a port and there's a choice between a comfortable marina berth or hanging off a quay wall, the crew will simply slip away and discreetly pay for a marina berth, and then tell the skipper it's a done deal.

Equally, when ashore for a meal, one of the crew will usually sidle off and pay for everyone when no-one else is looking. But if the skipper thinks the day has gone particularly well, you'll sometimes find he's paid for it all himself, As for getting diesel, whoever is carrying the cans will pay for it himself. Then too, when stores are required, it's covered by whoever goes to get them. It all sounds like an accountant's nightmare, yet so far, somehow at the end of the cruise everyone is content with the feeling that it has all balanced out, and as it has worked well for three years and longer, the attitude is that if it ain't broke, then don't try and fix it.

It had been hoped that Ainmara could stay on in the Dublin area for a week to do the Howth YC's Lambay Race in the Old Gaffers division on June 7th, as she won it in 1921. However, there was too much work still to be done to get her completely ready for a busy cruise programme coming rapidly down the line. But as she'll have to be back next year to defend the Leinster Trophy again, who knows but the double event might be done in 2015. As it was, her need for further fitting-out nearer to home was the saving of me, as a mighy temptation arose. The ancient Madcap from the north had stayed on in Dublin Bay, and was doing the Lambay Race with other old gaffers. The word on the waterfront is that Madcap may well be sold to France to be the centrepiece of a maritime museum in La Rochelle. So the Lambay Race might well be the last chance to sail on a 140-year-old boat. A place was secured on board.

The gaffers gather......Tir na nOg, Madcap and Naomh Cronan on misty morning in Howth before the Lambay Race. Photo: W M Nixon

Madcap's sensible accommodation (above and below) reflects the seagoing needs of the pilots for whom she was built140 years ago. Photo: W M Nixon