Displaying items by tag: Douglas Deane

Douglas Deane 1937-2019

The world of sailing in Ireland and internationally is much diminished by the sad passing of Douglas “Dougie” Deane of Crosshaven at the age of 82, after a very fully-lived life in which he contributed much to the sports with which he was involved, both in personal involvement and in several administrative roles, while at the same time being a life-enhancing and active member of the larger Crosshaven community in which he and his wife Liz had an extraordinarily generous family role.

Dougie Deane was the embodiment of all that is best in Cork life. He was excellent company with an infectious enjoyment of the moment, he was an able performer both as an individual and team player, and he quietly did much good work as he progressed through life.

Like many of his friends and family, he was deeply into sailing and rugby. His father Harry was Vice-Admiral of the Royal Cork Yacht Club from 1973 to 1975, and President of the legendary Cork Constitution Rugby Club, so-called because it was founded by staff members of the now long-defunct Cork newspaper of that name. But while Dougie was sufficiently involved with rugby to become a founder and later President of Crosshaven Rugby Club in which all of his five sons played, sailing was his special passion.

Dougie Deane crewed by Donal McClement racing Dusk in Cork Harbour in 1960

Dougie Deane crewed by Donal McClement racing Dusk in Cork Harbour in 1960

He became a junior member of the Royal Munster YC in Crosshaven in 1952, racing the IDRA 14 Maybe with Donal McClement, who was one of his many good friends - in Donal’s case, it was a lifelong camaraderie. They soon realised that while the O’Brien Kennedy-designed IDRA 14s were theoretically one-design, some boats were undoubtedly “more one-design than others”, and when they managed to move on from the appropriately-named Maybe to the legendary Dusk, major prizes started coming their way, with the prestigious Dognose Trophy being taken by the pair in 1959.

Leading Crosshaven sailors Sam Thompson (left) and Charlie Dwyer, with the new winners of the Dognose Trophy in 1959, Douglas Deane and Donal McClement (right)

Leading Crosshaven sailors Sam Thompson (left) and Charlie Dwyer, with the new winners of the Dognose Trophy in 1959, Douglas Deane and Donal McClement (right) Dusk as she is today, restored in a WEST project by the father-and-son team of Tom and David O’Brien, and being raced here by Andy Sargent in the 2016 IDRA 14 70th Anniversary Race at Clontarf, when she finished second. Photo: W M Nixon

Dusk as she is today, restored in a WEST project by the father-and-son team of Tom and David O’Brien, and being raced here by Andy Sargent in the 2016 IDRA 14 70th Anniversary Race at Clontarf, when she finished second. Photo: W M Nixon

But the young Dougie’s talents had already been well-recognised as early as 1955 when, with George Henry, he formed part of the Ireland team in the International Junior Regatta at Dun Laoghaire, a pioneering effort at a time when junior sailing as a category on its own was only beginning to be developed in Ireland.

Dougie Deane (right) with George Henry of Dun Laoghaire preparing to race in Mermaids at the International Junior Regatta in Dun Laoghaire in 1955.

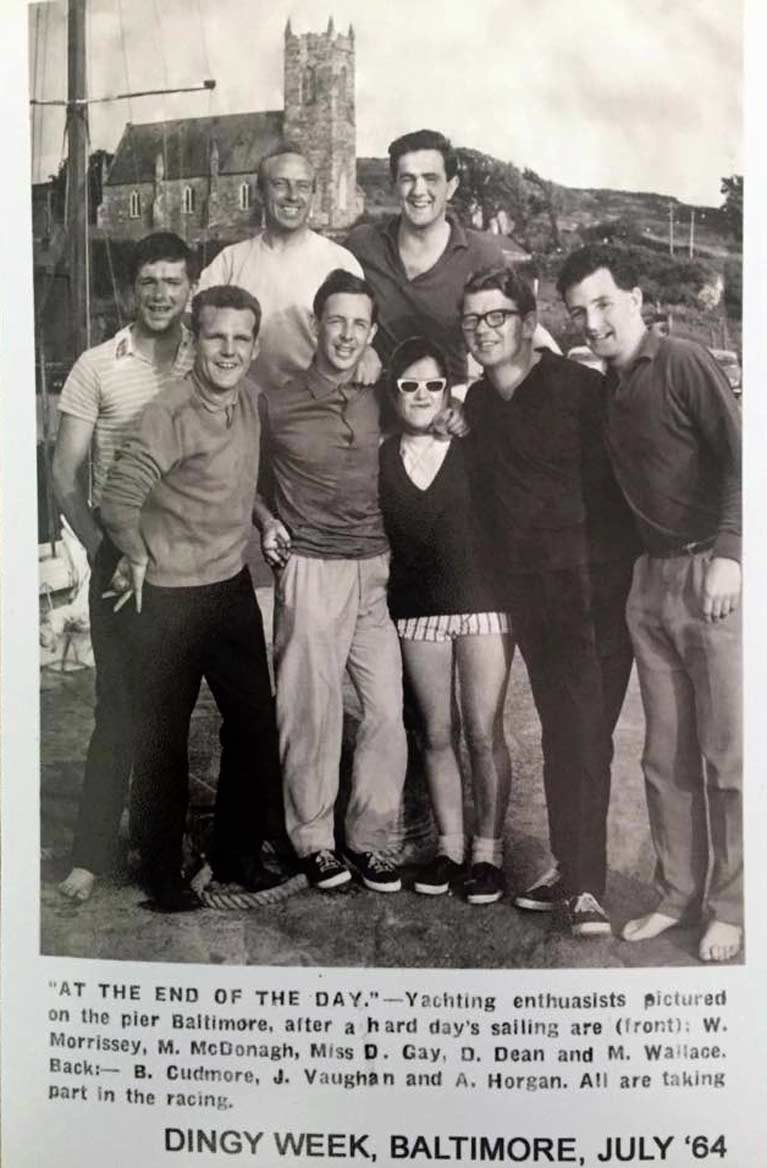

Dougie Deane (right) with George Henry of Dun Laoghaire preparing to race in Mermaids at the International Junior Regatta in Dun Laoghaire in 1955. Press cutting from Baltimore in 1964 – it took the Cork Examiner a day or two to recover from that spelling of Dinghy Week……

Press cutting from Baltimore in 1964 – it took the Cork Examiner a day or two to recover from that spelling of Dinghy Week……

His dinghy interests went on to take in busy campaigns as an owner with an International 505 and a National 18. But in classic Crosshaven style, his sailing abilities were readily transferred to cruising and offshore racing, and in 1965 he became a member of the Irish Cruising Club mainly on the strength of a voyage to Spain with Stan Roche, Joe Fitzgerald and Charlie Howlett on Stan Roche’s characterful 29-ton ketch Nancy Bet.

Stan Roche’s 29-ton ketch Nancy Bet, in which the young Dougie Deane cruised to Spain

Stan Roche’s 29-ton ketch Nancy Bet, in which the young Dougie Deane cruised to Spain Offshore sailing, with any hardship minimized by appropriate medication…(left to right) Dougie Deane with Charlie Howlett almost invisible behind him, Joe Fitzgerald and Stan Roche at sea on board the latter’s Nancy Bet.

Offshore sailing, with any hardship minimized by appropriate medication…(left to right) Dougie Deane with Charlie Howlett almost invisible behind him, Joe Fitzgerald and Stan Roche at sea on board the latter’s Nancy Bet.

In the work side of life, he had started early with what was to become Irish Distillers in their Cork administrative centre, where he went on to become Manager, and those managerial and administrative skills were quickly recognized in the sailing world, where he was a youthful member of the Royal Munster committee, rising to become Rear Commodore in 1965.

Then when the Royal Munster and the Royal Cork amalgamated in 1966-67 to become the Royal Cork Yacht Club in time for the Quarter Millennium in 1970, he was on the new RCYC General Committee when it first met in March 1967.

Thus he was to play a key role in the complex yet very successful Quarter Millennial Celebrations of 1969-70, and was much looked up to, as one who had actively been there for the Quarter Millennium, in order to give highly-valued advice for the up-coming Royal Cork Tricentenary next year. When his final illness struck with extreme rapidity, this made his sudden loss particularly painful in Crosshaven, where his eldest son Gavin is CEO of the Royal Cork YC, and had already been drawing on his helpful father’s exceptional experience in planning the very special year ahead.

For Douglas Deane - in addition to his many other attributes - was a wonderful father and family man. He married Liz Lucey in 1972 with Brian Cudmore as his Best Man in a perfect example of the inter-linking of Cork sailing families - when Brian in turn went on to marry Eleanor, Douglas was their Best Man.

A wonderful couple – a recent photo of Liz and Dougie Deane

A wonderful couple – a recent photo of Liz and Dougie Deane

Douglas and Liz went on to have five sons and a daughter Lucy, Crosshaven youngsters through and through, yet with a much larger breadth of vision than their strong sense of belonging to one locality might suggest.

And there was generosity and love too – when Lucy was 16 and their family virtually raised, Dougie and Liz were faced with the sudden death of Liz’s sister who left two sons younger than Lucy - Andrew and James. They were simply taken into the generous Deane household in Crosshaven, and in the end Dougie and Liz raised a family of eight.

They were a wonderful pair together, yet Dougie was able to continue his sailing, going into cruiser-racer ownership for a while with a share in the 37ft Dalcassian, and then being a regular member of the O’Leary crew on several boats with the family name of Irish Mist, particularly the two Tonner Irish Mist III which, under a subsequent owner, was seriously damaged on a stranding in the entrance to Cork Harbour after a steering failure. When she was beautifully restored by Jim McCarthy, Dougie transferred to the McCarthy crew, and stayed with him when he sought a new direction with an X99.

When the new 26ft 1720 Cork Sportsboat concept to a design by Tony Castro was being developed in time for the 1994 season, Dougie Deane was an enthusiastic supporter, so much so that he was able to persuade his directors in Cork Gin to back him in buying 1720 Sportsboat Hull No 1, which very conspicuously became Cork Dry Gin, for this was a quarter of a century ago, and such advertising seemed the most natural thing in the world.

Today, Gavin Deane vividly remembers his first sail with his father in this new boat. While his father was not particularly athletic in appearance, like Dennis Conner he became something different at the helm of a sailing boat, particularly one with a performance edge. All his experience with IDRA 14s, the 505, and the National 18 came to the fore, and the new sports machine zapped across Cork Harbour at a prodigious speed with Dougie Deane serenely at the helm and everything under control.

Pioneering in 1994. The new Cork 1720 Sportsboat Cork Dry Gin – No 1 out of the hull mould – at smooth speed in Cork Harbour with Dougie Deane at the helm. He liked all his boats, but this was a special favourite.

Pioneering in 1994. The new Cork 1720 Sportsboat Cork Dry Gin – No 1 out of the hull mould – at smooth speed in Cork Harbour with Dougie Deane at the helm. He liked all his boats, but this was a special favourite.

It was a metaphor for the way he lived his life. Donal McClement says of him: “He was a gentleman in every possible sense of the word. Quiet spoken yet effective in communication, and very highly-respected and well-liked by all who knew him. And they were many”.

For the last ten years of his life, Dougie owned a Sea Ray 22 fast power-cruiser, built in Cork, capable of 20-25 knots, with a couple of bunks in a little cabin should the urge come on him for a night or two of convenient cruising, and handy for viewing the occasional race. But sailing continued to be his favourite way of being afloat, and he was day sailing with friends and family well into the summer of 2019.

Then there was a family holiday in the south of France, where at the age of 82 he was seen diving with enthusiasm into the blue Mediterranean, to the amazement of his grandchildren. On returning home, his illness quickly manifested itself, and for his friends, he was gone in five weeks. It was a shock, a great sadness, but with the healing help of time, we can see that here was a truly great man who led an exemplary life.

Our heartfelt condolences are with his extensive family and his many close friends.

WMN

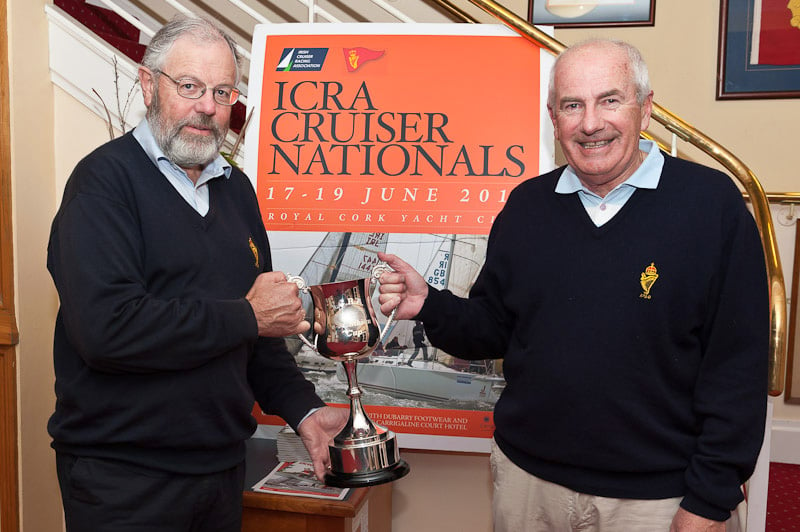

ICRA Launch Corinthian Cup

On Friday night last Barry Rose Commodore of the Irish Cruiser Racing Association launched the ICRA Corinthian Cup at the Royal Cork Yacht Club when Club Admiral Paddy McGlade was presented with the new trophy writes Claire Bateman. This cup will be the ultimate trophy for the non spinnaker fleet and carrying the same status of 'National Championship' at the ICRA National Championships. These events, to be sailed side by side, will give due recognition to both events and will add an element of fun and family competition to the whole scene.

Royal Cork Admiral Paddy McGlade receives the new trophy from ICRA Commodore Barry Rose. Photo: Bob Bateman

It was felt by ICRA that the idea of a Corinthian Cup event would reflect the spirit of inclusiveness being displayed by the non spinnaker sailors and means there are now two identical Cups offering equal status to both ECHO and IRC champions.

Admiral Paddy Mc Glade has placed the trophy on display in the Club Bar to encourage all the local non spinnaker (whitesail) fleet to enter the event to be hosted by the Royal Cork Yacht Club from 17th to 19th June.

Douglas Deane will be Race Officer for the non-spinnaker class so an event of the highest calibre is assured.