Displaying items by tag: Jimmy Fitzpatrick

Falling Faintly; a Poem for the Late Team Race Legend Jimmy Fitzpatrick

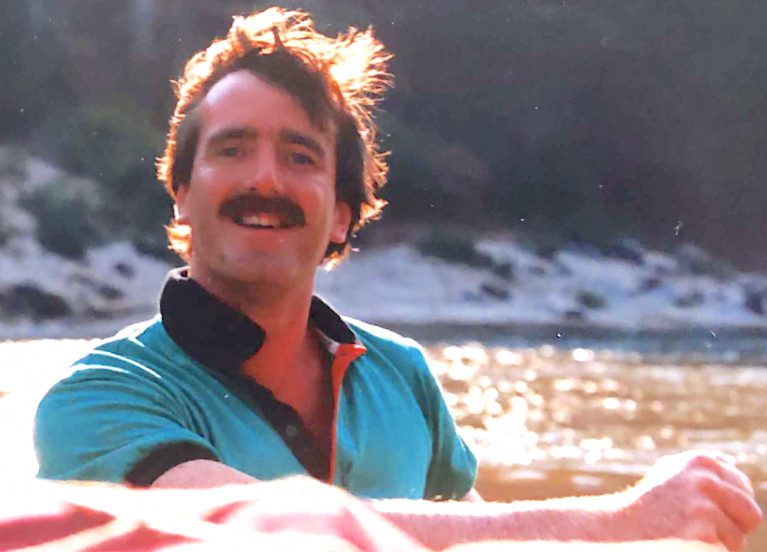

Writer Alison Hackett knew the late Jimmy Fitzpatrick as a great friend since her university sailing days in the 70s and 80s. Hackett says Jimmy's obituary written by David Sommerville on Afloat last week meant an awful lot to her and she has responded to the sadness she feels at the death of the team racing legend with a poem

FALLING FAINTLY

for Jimmy Fitzpatrick

Thinking of him as he left our house

for the last time, the gate open a little,

his absence not an absence but the possibility

of return; his laugh echoing from somewhere,

faint footsteps, the back and forth of him

unspooling in my mind.

I keep him close now, in private

conversations with myself, words

falling lightly, invisibly in quiet

dark, until a lightening dawn highlights

his mast on an arc of pink horizon,

spinnaker hoisted, wind behind,

showing me the way to the other side.

Alison Hackett

Jimmy Fitzpatrick 1957-2021

One of Dublin Bay's great sailing characters Jimmy Fitzpatrick of the Royal Irish Yacht Club has sadly passed away.

A true corinthian of sailing Jimmy Fitz was very well known both here and abroad. While he sailed out of the Royal Irish, he could be spotted most seasons holding court on the balconies of all the waterfront clubs. He was on first-name terms with everyone. All who met or sailed with Jimmy would agree that a friendlier, considerate or more entertaining companion was hard to find. He had a deep raucous laugh that was not easily missed.

In honour of Jimmy's life, the flags of each of the Royal Irish Yacht Club, the Royal St. George Yacht Club and the National Yacht Club were flown at half-mast on the day of his funeral last Thursday, January 28.

Like many, he was bitten by the bug when introduced to sailing at the age of seven by his brother Richard. Jimmy later became a head instructor with the Royal Irish and the Royal St George and also instructed in the National Yacht Club alongside current Dublin Bay Sailing Club Commodore Ann Kirwan.

He attended the 50th-anniversary dinner of the N.Y.C. junior section organised by Carmel Winkelmann, where many stories of regattas in Mount Shannon and Rosslare were regaled. Jimmy was very much the Rodney Marsh of sailing, moments of brilliance on the water while partying hard onshore. He knew what it was like to cross the line first in a Dragon Gold Cup race. Win a Wednesday night Wag race. In the Fireball Nationals in Sligo in the early 80s, he beat Adrian and Maeve Bell to a race gun.

Jimmy Fitzpatrick at the helm of his Fireball on Dublin Bay (with Michael Blaney on the wire) in the 1980s

Jimmy Fitzpatrick at the helm of his Fireball on Dublin Bay (with Michael Blaney on the wire) in the 1980s

At the time the Bells were in the top three in the world, on crossing the line Jimmy jumped overboard to celebrate and later that night the husband and wife duo magnanimously presented Jimmy and crew Mick Blaney with a bottle of Champagne. Years later, Jimmy and Mick nearly divorced when Jimmy simultaneously put the mast through the floor of the boat and his dad's garage roof in a late post regatta parking manoeuvre. Jimmy co-skippered alongside Mark Mansfield, a boat sponsored by his employers AIB in the 1988 Round Ireland Race. In 2004, Jimmy's nephew Rory represented Ireland at the Olympics in Greece. Jimmy worked hard behind the scenes to help Rory gather funds for the campaign to get him qualified.

It was when Jimmy got to UCD that his real passion in sailing developed; it was Team Racing. Jimmy competed in hundreds of team racing events over the years. He won the colours match for U.C.D. three years in a row setting the platform for the Rhinos (Spike, Joe Blaney & Marto Byrne) to go win it for another three years after that. In the '80s Jimmy moved to London and his flat became a focal point for not only Irish team racers but all the UK teams. He guest-helmed for the Nottingham Outlaws at the Illingworth trophy organised by HMRN. At the time the Outlaws were one of the top teams in the UK He set up his own team of sailors based in London and called them the Wild Geese. It was never clear what the criteria for qualification were but an ability to party was essential. Jimmy even managed to get a few West Kirby sailors to sail with the Wild Geese when short on numbers.

While competing at the Wilson Trophy one year, West Kirby had decided to try something different and hired a top sports commentator from Radio Liverpool to do some commentary on the team racing on the lake. They even installed a stand beside the caravan where the commentator was based. After a few hours, not even one man and his dog was watching or listening to what was unfolding and to make matters worse, the poor commentator knew nothing about sailing. Toll Smith a grandee of WKSC saddled up to Jimmy who was holding court in the wet bar and asked if he would mind spending a few minutes with the commentator to give him a few pointers on the sport. After a short conversation, the commentator from Liverpool Radio suggested to Jimmy he has a go at commentating on the next race. He passed the microphone to Jimmy and as they say the rest is history. Four hours later, Jimmy emerged from the caravan to a standing ovation from a full stand and a big crowd all around the lake. Jimmy later went on to commentate on the team racing worlds held in the Royal St.George, on the Sydney Olympics with RTE and was also invited to commentate with Sky Sports on a fledging International 14ft circuit.

Team racing appealed to Jimmy because he loved the camaraderie and people loved being in his company. He was very involved in the hearings on whether Commercial Cruise Ships should be allowed enter Dun Laoghaire Harbour. In the last decade, Jimmy struggled with his mental health, and many in the sailing community did their best to help him through difficult times.

Jimmy Fitzpatrick (third from right) sailing on Mick Blaney's (standing) 31.7 in the 2019 Volvo Dun Laoghaire Regatta Photo: Afloat

Jimmy Fitzpatrick (third from right) sailing on Mick Blaney's (standing) 31.7 in the 2019 Volvo Dun Laoghaire Regatta Photo: Afloat

Jimmy still managed to compete with Mick Blaney on his Beneteau 31.7 right up till racing was cancelled last July. Despite the pressures, he was going through his ability to spot a wind shift never left him. Jimmy would have been the first to point out that when we sail, we always take precautions for our own safety and that of our crew. So onshore let's not forget to take care of our mental safety and that of our friends.

Jimmy Fitzpatrick in his role as race officer for the Water Wags on Lough Boderg

Jimmy Fitzpatrick in his role as race officer for the Water Wags on Lough Boderg

Team racing and Dublin Bay will be the poorer for the loss of the unbridled enthusiasm of Jimmy Fitz. He only had one speed, and that was full-on.

Fair winds my friend.

DS

More photo memories of Jimmy have been provided by his friends and family here