Displaying items by tag: RNLI

Clifden RNLI Crewman Shares Lifesaving Skills On Danish Lifeboat

#RNLI - Clifden RNLI volunteer crewmember James 'Digger' Mullen was selected from thousands of RNLI volunteers to represent the charity last month on a European Lifeboat Crew Exchange in Denmark.

Lifeboat crew from seven European countries were invited on a week-long programme designed to improve maritime search and rescue (SAR) responses and help to prevent loss of life in Europe’s waters.

The initiative is run by the International Maritime Rescue Federation (IMRF) and comprises simulated search and rescue exercises as well as training modules, which were organised by the Danish Rescue Coast Service.

During an exhaustive week, Mullen had an opportunity to work with Danish lifeboat crew from three lifeboat stations and took part in various challenging scenarios with the Danish navy and the rescue helicopter crews.

Mullen, from the Clifden lifeboat in Co Galway, worked alongside lifeboat crew from Holland, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Iceland and Germany from a base in Hirtshals, a town on the north coast of Denmark. The area the local lifeboat crew operated in was completely different to Clifden with no breakers or islands off the coastline.

The group went to sea on Hirtshals lifeboat station’s two rescue boats: a 23m all-weather boat and a 9m fast response boat (FRB) that reaches speeds of up to 30 knots. The group travelled down the coast 40 miles to meet up with Thorup Strand lifeboat station and their 9m jet rescue boat Hurricane, which reaches speeds of 40 knots.

The team carried out a medical evacuation with a navy patrol boat and refueled the lifeboat at sea from the navy ship, while both vessels were travelling at 8 knots. The crew also took part in a joint lifeboat helicopter exercise; a common occurrence for lifeboat crew on Irish waters.

The week was full of simulated rescues and boat handling, with all the lifeboat crewmembers swapping their knowledge and feedback on what they found worked in different types of emergency scenarios in their own areas.

The final two days of the exercise were spent with the Danish navy and the team attended naval training school. They were taught how to board a life raft in big seas, how to abandon ship from a six metre bridge, and how to recover unconscious casualties into a liferaft.

At the end of the training there was a mass exercise. The pool was darkened, filled with smoke, wind, rain, lighting and thunder, and they evacuated their ship to find an unconscious casualty and recover them on to a nearby liferaft.

The final exercise was held in the navy fire fighting/damage control training centre. The group were taken onto a simulated navy ship and had to stem a growing ingress of water which was flowing in through numerous breeches and ultimately save the ship from sinking. This was to be done with timber, rubber mats, wedges, buckets, ropes, hand saws and hammers. In the freezing water which was pouring into the ship, the team all worked together to try and stem the flow and save the ship.

Commenting on the week, Mullen said: “I am extremely grateful that this exchange programme has been made possible through EU funding on the Lifelong Learning Programme. Our group of lifeboat crew from across Europe shared experiences with each other and listened to everyone’s feedback.

"Though we all spoke difference languages, we generally all do what we do the very same way, just using different boats with different equipment. Saving lives at sea is the same in every language."

RNLI divisional operations manager Owen Medland added: “We were delighted to have an RNLI volunteer crewmember on this exchange. The experience James has had in his role operating lifeboats off the west coast of Ireland is invaluable and we were keen to share this knowledge with a wider search and rescue community.

"There are always things we can learn from each other and it promotes a wider understanding of how saving lives at sea has evolved and continues to evolve due to improved equipment and continuing training.”

Major Search For Woman In Galway Docks Is False Alarm

#RNLI - Galway RNLI joined a major search for a woman believed to have entered the water at Galway Docks in the early hours of yesterday morning (Friday 1 November) that turned out to be a false alarm.

The Irish Coast Guard received a report about the missing woman shortly before 2am and immediately sought the assistance of Galway RNLI volunteer crew who launched the lifeboat from the nearby station within minutes.

Galway Fire Brigade and Mill Street Gardai searched the perimeter of the docks, including the boats and marina, while the Galway lifeboat searched the rest of the Docks.

They were joined in their efforts by coastguard rescue helicopter from about 3am but nothing was found.

After some investigation, it was discovered that the person who was reported missing was in fact safe and sound at another location.

Galway RNLI lifeboat operations manager Mike Swan said the search operation was eventually stood down at about 4am.

"While this incident proved to be a false alarm, Galway RNLI is always willing and ready to respond to anyone who is thought to be in danger in the water," said Swan.

"Each time the lifeboat is called out it costs the station up to €4,000. All of our lifeboat crew and land crew are volunteers and we rely solely on fundraising and the generosity of the public to keep the station and service running."

'Reindeer Runs' Return To Raise Funds For Irish Lifeboats

#RNLI - The hugely popular RNLI Reindeer Runs have returned to raise funds for the charity that saves lives at sea.

The event has fast become a favourite with families, runners and walkers, many of whom dress up in antlers to join in the fun and raise funds for the charity.

This year's Reindeer Runs are being held on Sunday 1 December at Marlay Park in Dublin and on Sunday 24 November at Fota House and Gardens in Carrigtwohill, Co Cork with a 5km and 10km walk or run, and a 1km Santa Saunter for younger participants.

RNLI community fundraising manager Pauline McGann is encouraging entrants to register early as places are limited.

"This is the fourth year of the RNLI Reindeer Runs and they have become hugely popular," she says. "They are now a major event on the charity’s Christmas calendar. We wanted to hold an event that would cater for everyone but would also have a large element of fun."

RNLI lifeboats are busy all year round but some of their most challenging callouts occur over the winter months in complete darkness.

This summer saw a 43 percent increase in the number of callouts RNLI lifeboats attended, with Irish lifeboats launched 571 times.

Among those taking part in the Dublin Reindeer Run will be Howth RNLI lifeboat mechanic Ian Sheridan and his family.

"We are so grateful to the many people who raise funds to keep the lifeboats afloat," says Sheridan. "The RNLI is a charity and relies on the generosity of the public to ensure that we can go to sea at any time to save lives with the best in equipment and training. People never know when they will need us but we will always be there."

Registration is now open and costs €10 for the saunter, €21 for the 5km and €23 for the 10km run or walk. There are also family and group rates available. All participants receive a limited edition RNLI Reindeer Run t-shirt and a pair of antlers.

Further information and registration details are available at rnli.org/reindeer or by emailing [email protected] for Dublin or [email protected] for Cork.

What Has Happened to Sailors' Traditional Self–Reliance At Sea?

#safetyonthewater –Can it really be true that lifeboat call-outs in Ireland in 2013 – most of them for recreational boating of some sort - showed a staggering increase of 43% over 2012? W M Nixon discusses the disturbing figures, and considers whether it is possible to re-build the traditional amateur seafaring tradition of competence and self-reliance.

Time was when the most respected sailing folk, the people with the highest standards in their boats and in their use of them for their dedicated style of seafaring, were accustomed to sail the sea on the principle that they would much rather drown than cause any inconvenience or danger to other seafarers in any way whatsoever.

This applied particularly in the matter of being rescued. Being rescued just wasn't done. It was a sign of appallingly poor seamanship. Indeed, having what other people might describe as an adventure of any kind was frowned upon. "An adventure" was looked upon by the pioneers of cruising - just as it was looked upon by their contemporaries, the top explorers - as evidence of incompetence.

It was an admirable if impossibly idealistic attitude, which had its roots in the earliest days of amateur seafaring. In that distant era, the first very few pioneers were venturing forth for pleasure on seas where working people with much less in the way of economic resources were struggling to make a usually poor and often dangerous living as fishermen. To emphasise the difference, pleasure sailors only fluttered about the place in summer like butterflies, whereas those who worked the sea in small boats had to face its ferocity all year round.

Also sharing the sea were the crews of cargo carrying vessels whose demanding owners did not welcome tales of their vessels being delayed and the valuable cargoes put at risk, even for the shortest possible periods, in order to assist or rescue some incompetent amateur. As for the regulators of the sea, the naval ships and the revenue cutters, they were naturally suspicious of people going about their inexplicable business with "pleasure" as their reported objective, sailing hither and yon in their strange little vessels.

They undoubtedly were "little" vessels, as the new sport of cruising with its codes of a high standard was developed by the emerging middle classes of the 19th Century. Unlike the aristocracy and monarchy, who would sail the sea in large yachts with crowds of attendants and everything – including rescue if needs be - done in a very public manner as part of the grand life's rich tableau, the middle classes valued privacy above everything else.

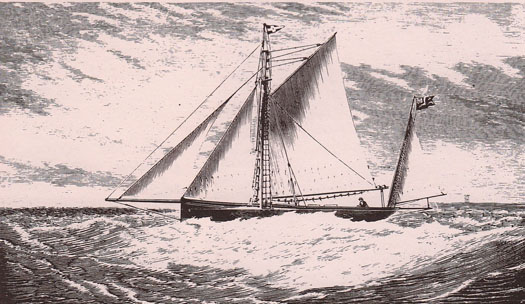

Thus the code of self-reliance in cruising evolved, propounded by folk like Richard Turrell McMullen, who developed the principle of total self-reliance to such an extent that even in coastal waters he cruised single-handed in his final years. And even when pleasure boats numbers and rescue services had developed to an impressive level in the late 20th Century, the "shame of being rescued" was still a very potent attitude which encouraged high standards in boat maintenance and seamanship.

Pioneering seafarer Richard Turrell McMullen in his 42ft Orion, with which he cruised the Irish coast in 1869. McMullen expounded a doctrine of self-reliance and competence in amateur sailors, and would have regarded being assisted by the lifeboats as a matter of extreme shame.

But today, well into the second decade of the 21st Century, the RNLI call-out figures for Ireland do not make happy reading for advocates of rugged seafaring self-reliance. Could it be that the ubiquitous presence of highly-visible lifeboats in our main harbours, with their presence further publicised at major rescues, is creating excessive haste in calling them out for non-emergency reasons?

Admittedly the summer of 2013 was so good that there were many more people afloat in June, July and August than in 2012's grim conditions. Thus many of those rescued will have been casual impulse boaters, rather than dedicated seafarers. But nevertheless a year-on-year increase of 43% in lifeboat launchings, most of them for recreational boating of some sort, is very discouraging for an activity which supposedly prides itself on its capacity for sensible self-regulation, and derives satisfaction from overcoming challenging conditions without assistance.

The Dun Laoghaire lifeboat on exercise in Dalkey Sound. This was Ireland's busiest station in the summer of 2013, with 34 call-outs in June, July and August Photo: David Branigan/Dun Laoghaire RNLI

For the record, Dun Laoghaire was the busiest station with 34 call outs. Portrush in County Antrim was next on 26, just ahead of Crosshaven with 25, while Fenit, Wicklow and Skerries (where their new boat, the Atlantic 85 Louis Stimson, was named and dedicated on Saturday September 7th) were all on 17.

The new lifeboat at Skerries, an Atlantic 85, was dedicated and named the Louis Simson on September 7th. The Skerries station had 17 call-outs during the three summer months.

Of course there are those who will claim that, in many instances, talking of "rescues" would be over-stating the case. When a situation looks like being serious from the outset, the Coastguards – and particularly their helicopter – will get involved. In fact, so many genuinely life-saving events involve helicopters that it's surprising no-one seems to have thought of a rescue helicopter service service funded by charities. Maybe they have, but have found it would be impossibly expensive. In any case, with lifeboats, there's the obvious and stirring maritime link. "Those in peril on the sea" must be one of the most recognisable phrases known to us, and providing charity support to lifeboats is a direct and very satisfying way of connecting with it.

But the fact that the lifeboats receive so much of their funding from charity, and are manned largely by volunteers, adds to the moral overtones when any rescue is successfully carried through. And as we cannot know how even the most minor boat difficulty might go pear-shaped at some future stage, then if the lifeboat gets involved, the perception is that you've been rescued however minor the problem may have been, and notwithstanding the fact that the lifeboatmen themselves may phrase their report to spare the rescued crew's blushes.

The lifeboatmen's attitude is better safe than sorry, and much better safe even if just slightly embarrassed. But an analysis of the incidents in Irish waters is intriguing, and they provided some events with unwelcome publicity. For instance, the ISA's Gathering Cruise-in-Company from Dun Laoghaire towards Dingle in July experienced four different lifeboat call-outs.

The highest-profile incident was the rescue of the crew of 30 from the tall ship Astrid when her engine failed on the short hop from Oysterhaven to Kinsale in fairly rough conditions of onshore winds. One possible story suggests that prior to her arrival in Ireland, one of Astrid's fuel tanks had been accidentally filled with fresh water, which is something that can easily happen in a large and complex old sailing ship during a busy turnaround time in port. In line with their spirit of self-reliance, Astrid's crew had reportedly declined offers of professional assistance in making the tanks diesel-ready again. But despite their best efforts, it seems there might have still been a small quantity of fresh water left, quite enough to cause what became a catastrophic engine stoppage.

The end of a dream. The sinking of the privately-owned Dutch sail-training tall ship Astrid was a catastrophe, but it wasn't a tragedy as all 30 on board were efficiently rescued by the lifeboats. Photo: Bob Bateman

In fairness to The Gathering Cruise-in-Company, the Astrid sinking was a big ship event with which they became associated almost incidentally. But the three other call-outs were directly linked. The second most serious (after the Astrid) of the Cruise-in-Company's call outs was for the Ballycotton Lifeboat for an injured crewman on a 42ft yacht six miles southwest of the port. Injuries were such that the casualty was transferred by lifeboat to a waiting ambulance at Ballycotton, then as the injured person was a key member of the 42ft yacht's crew of three, the lifeboat returned to the cruiser and escorted her to port.

The other two lifeboat callouts for the Cruise-in-Company were to assist a yacht with her propellor fouled by a fishing pot marker off Kilmore Quay, and to tow in one of the participating boats after her engine had failed off Kinsale.

The hazard of getting fouled in fishing pot lines is even greater in Ireland than other similar places like Cornwall, where Ben Ainslie has written of his family's experience of having their fine yacht driven ashore at the entrance of the Helford River and getting badly holed on rocks, after the propellor had knotted itself in a lobster pot line. The lobsters and crabs along the Irish coast being even more prolific, it's a constant problem when under power, and there are few challenges more daunting than motoring in late afternoon straight into the sun on passage from Carnsore Point to Kilmore Quay, and knowing that the entire route is a maze of pot markers, some quite clearly defined, others lurking just below the surface in the strong tides, and all virtually invisible with the notorious brightness of the sunny southeast right in your eyes.

So for cruising in Ireland, an obvious solution is one of those cunning little cutting devices fitted to the propshaft to slice through any ropes, but even they can be defeated by too much rope. When it does happen, a serrated bread knife with the means of and quick and easy attachment it to the boathook can sometimes work wonders.

But the proliferation of cruisers with SailDrives exacerbates the problem. They may fulfil the designer's dream of having the propellor immersed as deeply as possible, and in clear water too, but it means they're perfect targets for wayward pot lines, and you need a diver or a liftout to get at them if they become fouled.

But do propellers really need to be so deeply immersed? After all, in motorboats they're close under the surface, and often reasonably accessible by long-arm methods from a dinghy. Admittedly with a sailing boat with her extra pitching through having a mast, there is a danger that a shallow-mounted propellor will come out of the water as she punches into a head sea. But for years I'd a share in the Contessa 35 with a high-mounted propellor well aft, and it never came out of the water while motoring in a head sea. Yet thanks to the boat's pintail stern - which had few other merits - you could just about reach the prop from the dinghy, whereas today's wide-sterned boats might preclude that. Whatever, in re-aligning the engine in my current boat, something which just had to be done when I discovered the builders had installed it at an angle of 21 degrees plus, when the manufacturers insist it should be no more than 15 degrees with 7 degrees is an ideal target, I now have a setup where the propellor can be reached by clambering down the stern boarding ladder.

All of which is little enough comfort for a cruising boat with a fouled propellor being rescued by the Kilmore Quay lifeboat during the Cruise-in-Company, but that in turn begs the question: Where were the other cruisers-in-company when this situation arose? The notion behind a cruise-in-company is that there's a feeling of mutual support, and minor problems can be dealt with by assistance from your fellow participants. But even in the companionability of a cruise-in-company, could it be that we've become so accustomed to hearing about the use of rescue services that even with buddy boats presumably near, an everyday get-you-home problem can still lead to an emergency call?

It seems to have happened with the lifeboat going to that engineless boat's aid off Kinsale and more recently the maritime community expressed shared embarrassment when the crew of a cruiser-racer of a notably able type called out the lifeboat when their engine failed as they sat becalmed off Wicklow Head.

But as boat numbers increase, professional privately-run services develop to meet the growing need for assistance like this. In boat-crowded places like Long Island Sound, and indeed on many parts of the coast of the USA, commercial assistance and get-you-home services have been a feature afloat for many decades. And anyone who has been around the Solent will be familiar with the SeaStart service, to which you can subscribe as a sort of insurance, and which now does commercially many of the tasks which used to take up too much of lifeboat time.

{youtube}VrqzFIfV1w4{/youtube}

Even the colours of their boats suggest that SeaStart is the same reassuring presence afloat as the AA is ashore.

Interestingly, SeaStart now sees its role as including the education of its less-experienced subscribers in order to raise their standards of boat and equipment maintenance, and improve their attitudes to sailing the sea. Yet because it's all being done by what is essentially a commercial organisation, those availing of its services don't feel themselves being morally oppressed by a do-gooder organisation or an interfering nanny state.

It works well in a densely-boat-populated area like the Solent region, but we have to face the reality that Ireland has an enormous and often rough coastline, and boat numbers are relatively very few, and often far between. So for now and the foreseeable future, most of us in day sailing, cruising and offshore racing are going to have to rely on self-regulation with a sensible attitude to seafaring, and the use of voluntary services supported by charitable donations in emergencies.

The situation is of course very different in inshore racing, where highly organised club rescue teams with their crash boats, and an admirable ethos of efficiency among their crews, set a standard of self-help and self-regulation which is a credit to our sport. But as soon as the scope of the event spreads from the purely local, and the boat-size goes beyond dinghies, we find ourselves interacting with national emergency and rescue services.

So in seeing the MOD 70 trimaran capsizing in Dublin Bay in June and observing the flurry of helicopter and lifeboat activity – all very necessary as two crew were soon in hospital, one for an extended stay with a severely fractured pelvis – we were seeing a new world. It's a situation very far removed indeed from the schooner America making her unaccompanied way across the Atlantic in 1851, with no contact with anyone until, without fuss or bother, she prepared for the historic race around the Isle of Wight which in its turn was sailed without any expectation of the use of rescue services.

And for those of us in the less exalted areas of personal choice sailing, it really is a matter of self-regulation if we are going to avoid having the authorities impose regulation upon us. In considering this disturbing 43% increase in lifeboat call-outs in 2013, it's difficult to avoid the conclusion that the only reason there aren't threatening rumbles of regulation and inspection from the government is simply because of the dire circumstances of the national finances.

Were we not in a situation of government cutbacks on every front, it's highly likely there'd already be some advisory body looking at ways of making the boating world adopt a more responsible, self-reliant and disciplined attitude towards its activities. That in turn would lead to an increased inspectorate and more supervision, with further erosion of the sense of freedom in sailing the sea. And in the end, it's boat people who would have to pay for it themselves. It's up to us to protect this activity we cherish so much, and to treat it with the respect it deserves.

Holyhead Lifeboat Rescues Man Clinging To Rope In Harbour

#RNLI - Holyhead RNLI's inshore lifeboat launched in the early hours of yesterday morning (28 October) to help recover a man from the harbour in severe hypothermic condition.

- volunteers took the male in his late twenties from the water in the inner harbour at 4.40am after a member of the public heard the cries for help from his bed and alerted rescue services.

On arrival, the man was hanging onto a rope and face down near the water in the inner harbour of the Irish Sea port, a busy terminus for ferry crossings from Ireland to Wales.

The volunteer crew lifted him onboard the lifeboat and quickly transferred him to a waiting ambulance and coastguard team.

#RNLI - Lough Derg RNLI's lifeboat launched following two separate 999 calls from members of the public reporting that they had heard calls for help from the lake at Two Mile Gate on Friday afternoon (25 October).

Valentia Coast Guard requested the Lough Derg lifeboat to launch to search an area near Two Mile Gate, on the south-western shore of Lough Derg close to Killaloe, following two separate emergency calls reporting that that cries for help were heard, and with the possibility of two people in the water.

The lifeboat launched at 12.25pm with helm Eleanor Hooker, Tom Dunne and Jason Freeman on board. Winds were south-westerly, Force 2-3, with very good visibility.

Meanwhile, the Irish Coast Guard's Shannon-based search and rescue helicopter took off from its base, and Killaloe Coast Guard Rescue was also assisting.

Upon arrival on scene at 12.48pm, all three teams immediately carried sector searches of the area. RNLI volunteer Ben Ronayne was afloat in his RIB and also helped with the search. There were no reports of anyone missing.

At 3.15pm, following an extensive and exhaustive search of the area, Valentia Coast Guard stood down all agencies and the Lough Derg lifeboat returned to station.

Lough Derg RNLI helm Eleanor Hooker said that the lifeboat "in co-operation with our colleagues in the coastguard, made an extensive search of the area, before being stood down by Valentia Coast Guard when nothing was found."

Lough Derg RNLI Lifeboat Launches After 999 Calls

#rnli – Lough Derg RNLI Lifeboat launched following two separate 999 calls from members of the public, reporting that they had heard calls for help from the lake at Two Mile Gate.

At 12.15pm this afternoon, Valentia Coast Guard requested Lough Derg RNLI Lifeboat to launch to search an area near Two Mile Gate, on the South Western shore of Lough Derg, close to Killaloe, following two separate emergency calls that cries for help were heard, and with the possibility of two people in the water.

The lifeboat launched at 12.25pm with Helm Eleanor Hooker, Tom Dunne and Jason Freeman on board. Winds were south westerly, Force 2-3, visibility was very good. The RNLI lifeboat was on scene at 12.48pm, the Irish Coast Guard Search & Rescue Helicopter took off from its base at Shannon, and Killaloe Coast Guard Rescue was also assisting. Upon arrival on scene, all three immediately carried sector searches of the area. RNLI volunteer Ben Ronayne was afloat in his RIB and also helped with the search. There were no reports of anyone missing.

At 3.15pm following an extensive and exhaustive search of the area, Valentia Coast Guard stood down all agencies and Lough Derg RNLI Lifeboat returned to Station.

Lough Derg RNLI helm Eleanor Hooker said that the 'lifeboat, in co-operation with our colleagues in the Coast Guard, made an extensive search of the area, before being stood down by Valentia Coast Guard, when nothing was found'.

The Lifeboat returned to station and was ready for service again at 3.45hrs.

Kilrush Lifeboat Diverts From Training To Remove Floating Object

#RNLI - Kilrush RNLI was on a regular training exercise on Tuesday evening 22 October when a member of the public informed them of an object floating in the water about one mile east of Cappa Pier on the Shannon Estuary in Co Clare.

The volunteer crew informed Shannon Coast Guard, which in turn requested that the inshore lifeboat, helmed by Pauline Dunleavy, divert to the location.

Within minutes the crew had a vision of a 15ft-long piece of tree root floating by Aylevarroo. They quickly brought it aboard the lifeboat, securing it at the stern of the boat.

On returning to the station, Kilrush RNLI deputy launching authority Fintan Keating Sr paid tribute to the member of the public who spotted the object in the water.

"If the item had crossed the path of the Shannon car ferry or other boats on the river, we could have encountered a worse situation," he said. "It’s always good to dial 112 or 999 if people are ever concerned."

Holyhead Lifeboat Rescues Kayakers From Irish Sea

#RNLI - Holyhead's all-weather lifeboat and volunteer crew launched on service to six kayaks in difficulty off Middle Mouse in the Irish Sea north of Anglesey in Wales last Sunday (20 October).

One of the party reportedly capsized and was in the sea for some time, but with help was recovered.

- Sea King helicopter from RAF Valley kept the party in sight until the lifeboat arrived. Cemaes Bay coastguard were also on shore watching and relaying information to the coastguard at Holyhead.

All the kayakers were rescued by the all-weather lifeboat from Holyhead RNLI and brought to the safety of Holyhead Marina.

Arranmore Lifeboat Crew Undergo Special First Aid Training

#RNLI - Life for the RNLI’s volunteer lifeboat crews doesn’t stop when they come ashore from a call-out. Once the lifeboat is safely back at anchor, the crew then attend training which ensures that each crew member can carry on saving lives at sea.

The Arranmore RNLI Lifeboat crew are currently attending a first aid course at their lifeboat station on the west Donegal island. Such competence-based training (or CBT) is an integral part of each crew member’s role in their life aving work on the lifeboats.

Each crew member can avail of training in various disciplines including navigation, boat handling, communications and at present first aid.

According the RNLI, the organisation prides itself on providing the best possible training for each crew member and is continually engaged in research to provide best practice for saving lives at sea.

Casualty care is a crucial link in the search and rescue (SAR) chain that allows lifeboat crews to save lives at sea. Having utilised their previously learned skills to save lives and rescue casualties at sea, continued training assists crew members to provide casualties with the best possible chance of survival, often in a hostile, unforgiving environment and many miles from professional hospital-based care.

Maritime SAR medicine is a specialised field, and the RNLI provides a bespoke course that prepares crew to manage any emergency encountered in the operational field of the RNLI.

The first aid course being provided to RNLI crew members throughout Ireland and the UK at the moment is specifically designed to depart as far as practical from the mainstream occupational first aid courses and focus on providing crew members with the maximum amount of knowledge to deal with emergencies at sea.

The training has a hands-on approach rather than complex theory or diagnosis, and empowers crew members to confidently and competently treat casualties. This approach is reinforced by a unique treatment check card, which takes the guesswork out of treating casualties.

The type of emergencies lifeboat crews deal with are, at a basic level, similar to emergencies one encounters on shore, and can involve loss of limbs, burns, breathing difficulties and heart problems - but are sometimes many miles from a mainland hospital, and only the expertise of the lifeboat crew (without having to rely on memory, because of the card reference system operated by the RNLI) can mean the difference between life and death.

The course is accredited by the RNLI Medical and Survival Committee and the Trauma and Critical Care Group, and is approved by the Royal College of Surgeons and the paramedic department. The system itself is highly regarded by many other emergency services as it is being continually reassessed and upgraded.

The course is delivered at a time and place, usually at the local lifeboat station, that’s convenient to crew members and is the last of this course to be delivered prior to the next upgrade in January 2014. The new changes will include a portable stretcher that can be accommodated in the smaller class inshore lifeboats; the introduction of the use of drugs to alleviate breathing difficulties; the use of more user-friendly check cards; and the reassessment of the treatment of head injuries at sea.

RNLI trainer Trevor Stevens said: “The training which crew members receive is specially designed so that each crew member is guided by the same protocols no matter where, within the spectrum of the RNLI, they operate.

“We are confident that our voluntary crew can competently deal with any emergency, large or small to a high standard and it is the aim of the RNLI to provide the best possible training to our voluntary crew.”