Displaying items by tag: Sea Stack

Sea Stack Scaled By Adventurous Climbers For First Time In 25 Years

#SeaStack - A famous sea stack off the Co Mayo coast has been climbed for the first time in more than 25 years, as Independent.ie Travel reports.

At the end of August, Iain Miller and his climbing partner Paulina Kaniszewska reached the top of Dún Briste, off Downpatrick Head, in what was the third attempt by the former to summit the 50m rock.

One of the more breathtaking spots along the Wild Atlantic Way, it's also considered a particularly dangerous climb that should only be attempted by experts.

But for Miller, the rewards for scaling the summit of a place that has seen fewer visitors on record than men on the moon were more than he could put into words.

Independent.ie Travel has more on the story HERE.

The Sea Stacks of Donegal

The county of Donegal at the North West tip of Ireland boasts two major Irish mountain ranges, over thousand kilometres of coastline, one hundred sea stacks and many diverse climbing locations writes Ian Miller. Donegal currently plays host to many lifetimes worth of world class rock climbing in some of the most beautiful and unspoilt Locations in Ireland. The scope for further exploration and the opportunity to discover unclimbed rock is almost unlimited, as there is an unexplored adventure waiting through every mountain pass and around every remote headland. There is a wealth different types of climbing venues found throughout Donegal from easy accessible road side venues though to huge mountain cliffs found high in the remote Donegal mountains.

What the coast line of Donegal provides for an adventurous rock climber is more rock climbing venues, routes and unclimbed rock than the rest of Ireland combined. The wealth and diversity of the climbing available along this coast line is almost unlimited from the mud stone roof at Muckross in the south of the county to the Granite slabs at Malin head, (Irelands most northerly point) in the North of the county. County Donegal boasts Irelands longest rock climb, the 750 meter long Sturrall Ridge, Irelands highest sea stack, the 150m Tormore Island and Irelands highest mountain crag in the Poison Glen. There are currently over 2800 recorded rock climbs on over 150 cliff faces scattered throughout the county.

Where the rock climbing on Donegal’s coast line truly excels itself is in its sea stacks. There are a shade under 100 sea stacks with currently just over 150 recorded routes to their summits. The sea stacks are found along the coast of Donegal’s mainland and its western islands sit in some of the most remote, isolated and hostile coastal locations in Ireland. What these sea stacks provide is a large collection of the most adventurous, remote and atmospheric rock climbs in Ireland.

Sea stack climbing involves accessing huge towers of rock that stick out of the sea, it is this access that makes these locations so special. A day out on a sea stack will typically require a 250 meter descent to sea level to access an isolated storm beach, where it is highly unlikely anyone has ever stood before. This is followed by an UBER committing sea passage along the bases of currently unclimbed 250 meter high sea cliffs in a totally committed and potentially unescapable locations, this will allow you to gain the bases of the sea stacks. The commitment required and the sense of primal fear that accompanies these marine journeys has to experienced to be understood.

. As always, tad of logistics and planning is the key to success and of course the adoption of perhaps less orthodox climbing equipment such as 600m of 6mm polypro, a lightweight Lidl Dingy, a single lightweight paddle, divers booties, a 20ft Cordette, a pair of Speedo’s, heavy duty dry bags, 20m of 12mm polyprop, an alpine hammer, a snow bar, a selection of pegs, a chest harness/inverted Gri-Gri combo and a big Grin! We then climb these towers of rock to arrive on pristine pinpoint summits far from anywhere in the real world. Standing on a pinpoint summit over 100m above the ocean, 500m from the nearest point of land and 20KM from the nearest main road can easily be described as a truly spiritual experience.

Donegal Sea Stacks

Since 2007 I have been exploring the sea stacks of County Donegal, and have currently climbed over 60 previously unclimbed sea stacks along the coast of the county and recorded over 150 new routes on Donegal's Sea Stacks. During these adventures we have seen and experienced firsthand the true beauty of these little known places in coastal Ireland.

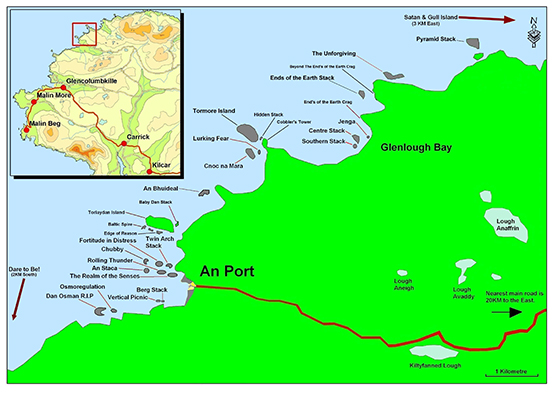

The main residence of the sea stacks is the Slievetooey coastline in the South West of the county, access to this coastline is by a narrow winding 20 km B road which takes you to the An Port road end.

An Staca sea stack

An Port is quite simply the most beautiful location in Ireland a trip to this road end is an outstanding journey in its own right, but it’s what lives either side of this road end that makes it a mind blowing location. To the south of An Port lives a chain four sea stacks each with an increase in commitment and concern to reach their bases as they span further and further away from the remote storm beach launch pad facing Berg Stack. (link 4) To the South of these stacks the skyline is dominated by the Sturrall Headland, which provides an 750 meter rock climb which requires a 300 meter sea passage to reach its most sea ward tip. The rock climbing grade of this headland is given the little used XS grade as it means there is much more than rock climbing skills required for a safe ascent. Approx a third of the way up the ridge there is a 50 meter long section of climbing that will live forever in your memory!

To the south of An Port lives a chain four sea stacks each with an increase in commitment and concern to reach their bases as they span further and further away from the remote storm beach launch pad facing Berg Stack. (link 4) To the South of these stacks the skyline is dominated by the Sturrall Headland, which provides an 750 meter rock climb which requires a 300 meter sea passage to reach its most sea ward tip. The rock climbing grade of this headland is given the little used XS grade as it means there is much more than rock climbing skills required for a safe ascent. Approx a third of the way up the ridge there is a 50 meter long section of climbing that will live forever in your memory!

An Port South

Travelling North from An Port the sea cliffs and sea stacks just get bigger and bigger. After about a 600 meter cliff top walk you will be overlooking the 90 meter high Toralaydan island. (Link 6) Living on its south and North sides are a further very difficult to access sea stacks. At the sea ward tip of its south side lives the Baltic Tower a route up its sea ward face provides a very scary climb called Icon, and at a very amenable climbing grade it provides a climb on immaculate rock in a terrifying nautical location.

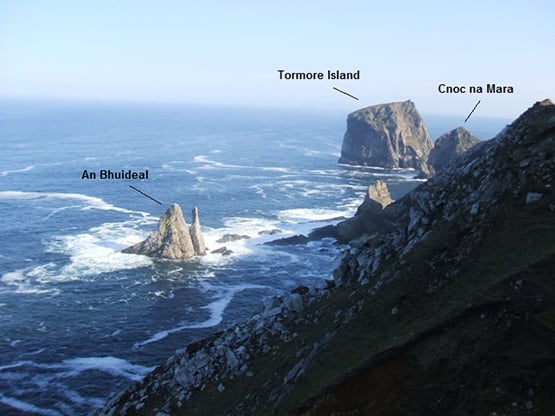

A further 500m to the North of Toralaydan Island lives An Bhuideal (The Bottle, as its north summit looks like a milk bottle when seen from the sea) an immaculate and iconic twin headed stack. There are currently three routes to its twin summits and all three are world class adventurous rock climbs. The super skinny North tower of this stack provides an unforgettable experience of three pitch climbing to its tiny and extremely exposed summit. The abseil descent from this micro summit involves a wee bit of prayer as the summit abseil anchors are a cairn of rocks and the landward face overhang alarmingly in its upper half. It is a very scary place to be! ☺

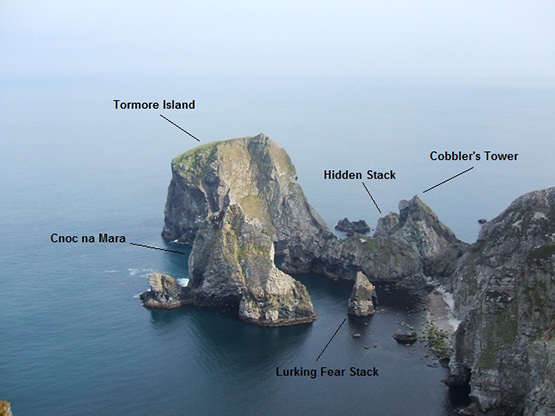

Travelling a further kilometre North along the coast from An Bhuideal takes you to a stunning cliff top viewpoint over looking Tormore Island, Irelands highest sea stack. Living in the shadow of Tormore Island is the 100 meter high Cnoc na Mara, it is difficult not to get emotional when talking about the mighty Cnoc na Mara.

Cnoc na mara Solo

Cnoc na Mara

When I first saw this 100m sea stack from the overlooking cliff tops it was the inspiration to climb every unclimbed sea stack in Donegal. It is safe to say this stack represents all that is great about adventure climbing. It's impressive soaring 150 meter long landward arete provides one of the most rewarding and adventurous rock climbs in Ireland. It is easily an equal to the mighty Old Man of Hoy off the Orkney Islands in the north of Scotland. Access is by a monsterous steep grassy descent followed by a 20 meter abseil to a storm beach at the entrance to Shambhala. As you descent this steep slope, sitting out to sea Cnoc na Mara grows with height as you descend reaching epic proportions as you get closer to the beach. Gaining the beach alone is an adventurous undertaking in its own right and is an excellent taster off what is to come. From the beach you paddle out for about 120 meter to the reach the base of the stack. The Landward arête of the stack is climbed in four pitches each pitch being much more atmospheric than the previous. The fourth pitch being the money shot as it is a 58 meter ridge traverse with 100 meters of air either side of you as you negotiate the short steep sections along this outstanding ridge traverse.

Gaining the summit is like being reborn into a world where anything is possible, it truly is a surreal and magical place to be. The whole world falls away below and around you, as you are perched on a summit far from anything else in the real world.

Paddle around Tormore Island

Tormore Island is a gigantic leviathan, a sentinel of the deep standing guard at the nautical gates of the Slievetooey coastline. At 150 meters above sea level at its highest point above the ocean it is Ireland's highest sea stack. This huge square topped sea stack can be seen for many kilometres along the coast either side of it. It can even be clearly seen from the Dungloe/Kincaslough road some 40 Kilometres to the north. Access is a very involved and emotional affair and entails gaining the storm beach as for Cnoc na Mara, Lurking Fear and Tormore Island. From here it is a 500 meter long sea passage around the headland to the north of the storm beach and a further 250 meter paddle through the outstanding channel separating Tormore Island and Cobblers Tower on the Donegal mainland. At the northern end of the land ward face of Tormore Island there is a huge non tidal ledge just above the high water mark.

In 2008 a team of four climbers travelled by 250 horse power RiB and landed on the land ward face of the stack. Two members of the party had made several previous attempts to land on and climb the stack in the past. We were aware of the story of the man who was buried here. During our climb of the stack we searched any possible place where someone could be buried and found no possible burial site or any trace of the passage of people on the stack prior to our ascent. We found no evidence or trace of previous visitors on the summit. To get off the summit back to sea level we made four 50 meter abseils leaving behind two 240 cm slings and 5 pitons as abseil anchors.

We climbed the very obvious land ward arete at the northern end of the land ward face of the sea stack, This huge feature can be easily seen from any position along the coast overlooking the stack. The route we took to the summit was climbed in 5 long pitches following the easiest climbing we could find up this huge feature.

To the North of the Tormore Island view point, the coastline falls away into Glenlough bay, a truly spectacular bay containing a further 4 sea stacks and Irelands largest raised shingle storm beach. On a day of huge north west sea motion the roar of a billions of tonnes of shingle being moved up and down the beach by the incoming seas can be deafening even from the cliff tops 200 meters above the beach.

To the north of Glenlough bay the land swings 90 degrees to face north and for a distance of 7 kilometres the sea cliffs increase to 300 meters high. At the base of these monster sea cliffs are a further four extremely inaccessible sea stacks, the 60 meters high Unforgiven Stack, the 50 meter high Pyramid Stack, the 80 meter high Satan and the 90 meter high Gull Island. Of these sea stacks Satan is the daddy, This sea stack is one of the most fearsome and dangerous stacks in Ireland. It sits off the north west face of the mighty Gull Island and presents considerable logistical and nautical access problems requiring a tad of nautical planning prior to attempting an ascent.

The most remote place in Ireland?

Access is by walking 4KM over the Slievetooey summit from the south and descending it's northern slopes to an outstanding location on the clifftops over looking Gull Island. Descend the very steep grass to the boulder beach joining Gull Island to the mainland. There is an abseil stake in place (2009) to safeguard the initial part of the descent. Once on the boulder beach paddle 500 or so meters west along the base of Gull Island to the entrance of a surreal gothic channel separating Satan and Gull Island. This channel is outrageous and leads you to the only landing place on the stack. Land on the stack at the convergance of the channels in the centre of this gothic labyrinth.

The stack was climbed in three pitches up it's south face culminating in a superb final pitch up a steep groove and rocky ridge traverse onto the majestic and super scary summit. The stack is so named as, if you make a mess of it the beast will take your soul.

Solo First Ascent

The Icon

Owey Island

Centre Stack

For more information click here to down load Iain Millers' free guidebook