Displaying items by tag: W M Nixon

Sailing Towards Better Communications in the Digital World

The Afloat.ie website, which is ranked by Google as Ireland’s leading source for the provision of a broad range of recreational and commercial maritime information, news and comment, has been completely updated in recent weeks. Yet though it has acquired a fresh, fast-moving look, and now provides a new and unrivalled multi-platform service, the change has been effected without any interruption to service. That said, our alert and more tech-savvy readers have been welcoming each addition to our service as it comes online. The new-style Afloat.ie is both a ground-breaking development for maritime communications and news exchange and analysis in Ireland, and yet it is also a healthy continuation of an integral part of our maritime life which stretches back more than fifty years. W M Nixon takes up the tale, and looks forward to where this remarkable story might lead us all.

In the early 1960s the Irish Dinghy Racing Association (founded 1946) was in the process of being re-born as the Irish Yachting Association. A competitive three-boat Irish campaign had been mounted for the 1960 Rome Olympics with the sailing events in Naples, and the confidence gained from this project gave the nascent national authority new energy and clearer direction.

The proposed wider remit for the new IYA aimed to make the Association of interest to all sailing and boating enthusiasts, and a sub-committee - drawn from all the main sailing centres through the yacht and sailing clubs which were the core of the national authority - was set up to explore ways of establishing an Irish sailing and boating magazine to reach the small but growing home market.

The intention was that the IYA should publish the magazine itself, as it was not initially a valid stand-alone commercial proposition. The first Irish Yachting was the July/August edition of 1962, and it continued as a bi-monthly publication through the 1960s, relying for content largely on modestly-paid contributors – both specialist and regional - and the editorial and production work co-ordinated by IYA Secretary Ursula Maguire, with the Association underwriting the cost of a magazine whose income was augmented by advertising.

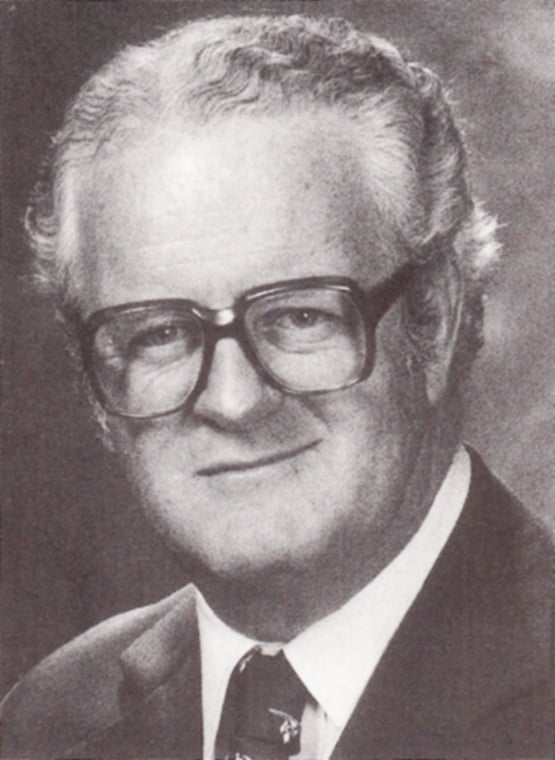

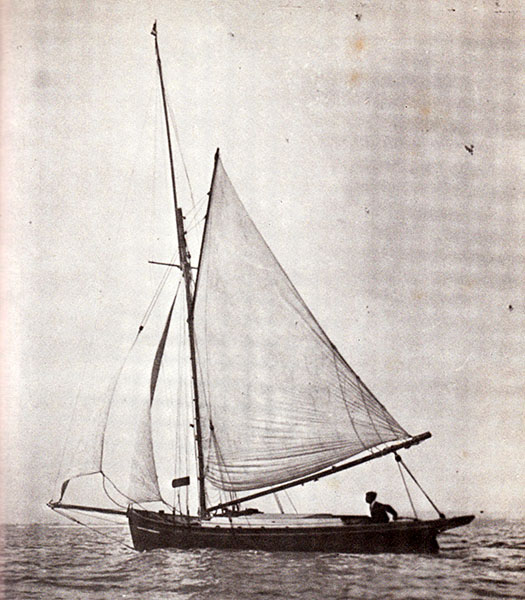

Clayton Love Jnr of Cork. Working closely with the late Jimmy Mooney of Dun Laoghaire, as President of the Irish Dinghy Racing Association he transformed it into the Irish Yachting Association, and together they co-ordinated the introduction of Irish Yachting magazine in 1962. In 1968 he was one of the small committee which oversaw the conversion of Erskine & Molly Childers’ famous Asgard to become Ireland’s first sail training vessel, and at the same time he was negotiating the amalgamation of the Royal Munster Yacht Club with the Royal Cork Yacht Club to have the Royal Cork YC thriving for its Quarter Millennium Celebration in1969-1970. A noted IDRA 14 and Int. 505 sailor, he won the Helsmans Championship, and in this photo, he is wearing the original IYA tie.

The hope had always been that the interest in sailing and boating in Ireland, with a developing marine industry to support it, would increase to such an extent that the magazine would become of interest to a commercial publisher, as it was felt that an in-house publication from a National Authority lacked the bite and broader interest to compete properly with the British yachting magazines which circulated widely in Ireland north and south.

In 1970 this aim was achieved, with the rights taken over by a commercial periodical publishing group which agreed that Irish Yachting & Motorboating – as it soon became – would be a monthly magazine which would guarantee space for specifically IYA news and policies, yet would equally expect to publish contrary views and incisive analyses.

Historic highlight. David Wilkins and Jamie Wilkinson win the Silver medal for Ireland in the Flying Dutchman Class at the 1980 Olympics

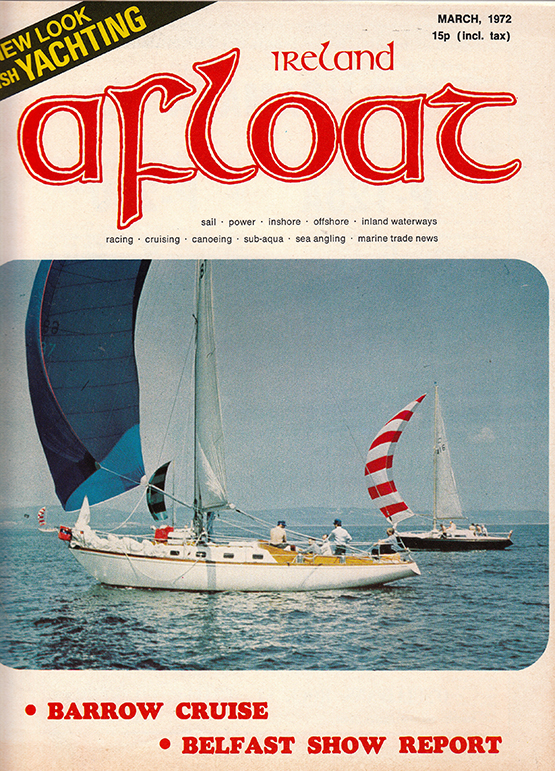

New look Irish Yachting: Afloat's first edition in 1972. Today's magazine and website covers the same Irish maritime topics as it did 43 years ago

At the same time it would make added efforts to reach potential newcomers in every area of boating, and general readers in all other areas of maritime interest. As a result of this, the magazine’s name was then changed to Afloat, and through the 1980s and the 1990s, with occasional changes of publishers, the magazine played a central role in the development and growth of Irish sailing and boating.

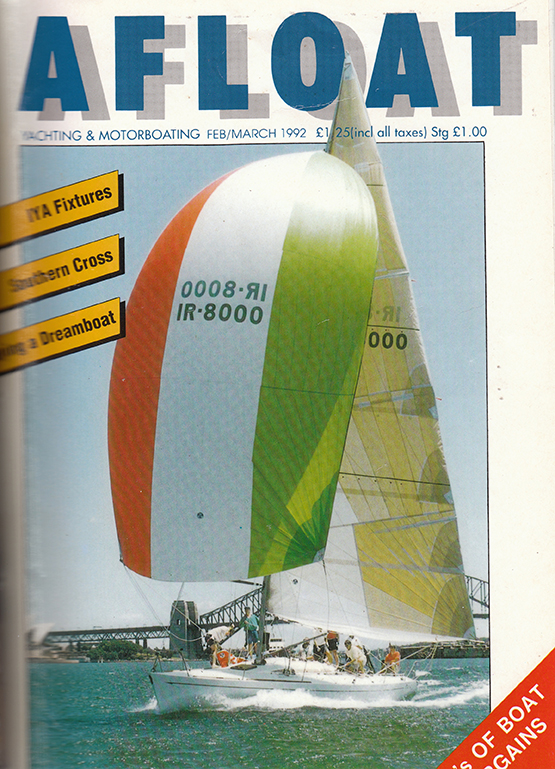

Going global. The Feb/March 1992 edition of Afloat celebrated Ireland’s win in both the December 1991 Southern Cross series, and the overall win in the Sydney-Hobart race 1991, with John Storey’s all-conquering Atara as our cover girl...

Since then, as our regular readers will be aware, over the past 20 years Afloat has been on a firm commercial footing and has developed into the comprehensive publication and Internet forum it is today. It continued to be so through the difficult times of recession, and through radical changes both in the Irish marine industry – the main supporters of the published version of Afloat Magazine – and the ways in which those marine manufacturers and traders reach their potential markets.

Another big international win, this time in the 21st century. Ger O’Rourke’s Cookson 50 Chieftain from Kilrush in the early stages of the Rolex Fastnet Race 2007, which she won overall. The Limerick skipper deservedly became Afloat.ie “Sailor of the Year” on the strength of this great achievement. Photo: James Boyd

Consolidation of the global marine industry, combined with the fact that Ireland is now within a very few hours flying time from the main centres of marine manufacturing, have meant that Ireland has become, in effect, a province of the European boat business.

Equally, the growth of the Internet has been such that international marine corporations have been able to develop websites of such quality that they by-pass established means of reaching potential customers. In the final analysis, these website constitute advertising. But they have now reached such a standard of sophistication that the uninformed reader sometimes has difficulty in differentiating a subtle sales pitch from genuine news and comment.

This re-direction of marketing budgets has inevitably impinged on established methods of communication and public conversation in the maritime sphere as elsewhere. But open media outlets such as Afloat.ie have in turn been re-inventing themselves in order to continue to provide their best possible service in an increasingly challenging environment.

In fact, Afloat magazine was one of the first to embrace new technology in the Internet age, with our initial website launched in 1993 with support from Allianz Insurance as Founding Sponsor. Now, some 53 years after Afloat first published on paper, it is the leader in Irish maritime communications online, while at the same time continuing to publish a quarterly version of the magazine on paper, with the Afloat Autumn 2015 edition hitting the news-stands next week.

Quarterly form – the up-coming Autumn 2015 Afloat, on sale next week

Today's scenario on the Internet is such that:

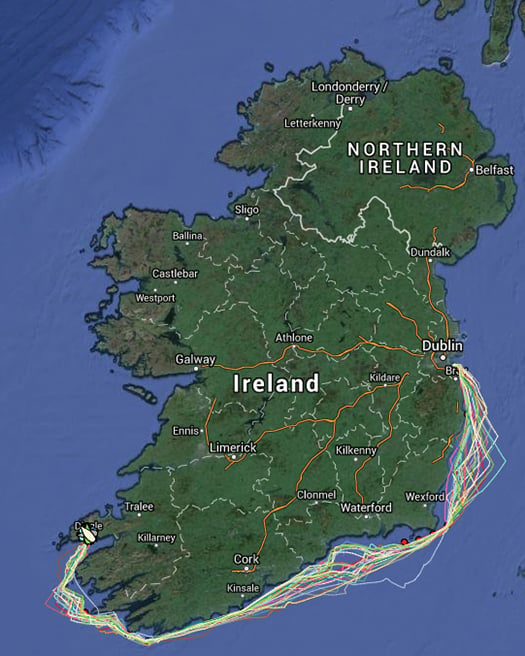

Afloat.ie's popular online format has a strong returning readership with around 48% of daily visits being return visitors. In fact over the peak sailing months in 2014 Afloat surpassed its own records for unique (direct) visitors with an average of 52,024 visitors a month, and as this graph shows, our key figures in 2015 are up 12%, with a significant further underlying rise towards the latter part of the season, though nothing quite matches the spike when Musandam Oman was establishing a new Round Ireland Record back in the Spring.

Afloat.ie's improving performance through 2015, with a spike for the successful Round Ireland record bid by Musandam Oman

The team works hard to achieve top Google Search rankings, and together with a tightly bound community of readers, Afloat.ie's continually up-dated combination of opinion, hard news and features puts it at the very heart of the national conversation on sailing, boating and maritime affairs.

It's a satisfying result to date because the aim has always been to provide Irish sailing clubs, classes and the wider maritime community with comprehensive and reliable information in a dynamic independent site to promote our sport to the wider audience which only the Internet provides.

This has been supported this year by the ISA with their renewal of a necessary relationship with Afloat.ie which in a sense marks a return to the situation in 1962. It’s probably a unique tie–up in world sailing, but is necessary because athough Ireland has all the status of a leading sailing nation, globally speaking we have a small national economy.

In addition, the internationalisation of the marine industry, and its increasing reliance on in-house digital communication for product publicity, means that the only significant income stream in Irish sailing and boating is through the clubs and the Sports Council grants which keep the ISA functioning.

The working agreement between the ISA and Afloat allows the association to use Afloat.ie’s sailing news feed and the use of Afloat's Sailor of the Year Award, and it is proving to be a successful link-up. It’s healthy in that Afloat.ie can provide a platform for much livelier discussions and topics than is the case with the ISA’s own website, which is obliged to be somewhat in the nature of a Government Gazette.

The Internet poses many problems, not least for traditional media, but in all my years as a sailing writer I have never seen the potential that exists for exciting Irish sailing communications as clearly as I do today with the current output from the Afloat website. It means that the spirit of the unique and lively Irish sailing and boating community is reflected by their means of communications with each other, and with the outside world.

The ISA has a valuable communications budget that needs to be spent very wisely to cover all areas of our sport, and to achieve this I would urge the ISA and Afloat to seek a stronger relationship. It would be a dynamic move which would help to provide additional communication services to sailing clubs throughout the country, while also reaching out to a wider market, and I am firmly of the opinion that it would fit well with the new direction that the reformed ISA is trying to take.

W M Nixon, seen here at last month’s Cruising Association of Ireland rally in Dublin, became Editor of Irish Yachting when it began commercial monthly publication in 1970. Photo: Aidan Coughlan

This weekend’s two-day All-Ireland Sailing Championship at the National Yacht Club in Dun Laoghaire, racing boats of the ISA J/80 SailFleet flotilla, is an easy target for facile criticism. Perhaps because it tries to do so much in the space of only two days racing, with just one type of boat and an entry of 15 class championship-winning helms, inevitably this means it will be seen by some as falling short of its high aspiration of providing a true Champion of Champions.

Yet it seldom fails to produce an absolute cracker of a final. Last year, current defending champion Anthony O’Leary of Cork, racing the J/80s in Howth and representing both ICRA Class 0 and the 1720 Sportsboats, snatched a last gasp win from 2013 title-holder Ben Duncan of the SB20s, thereby rounding out an utterly exceptional personal season for O’Leary which saw him go on to be very deservedly declared the Afloat.ie “Sailor of the Year” 2014.

So this year, with a host of younger challengers drawn from a remarkable variety of sailing backgrounds, the ever-youthful Anthony O’Leary might well see himself in the position of the Senior Stag defending his territory against half a dozen young bucks who will seem to attack him from several directions. And with winds forecast to increase in strength as the weekend progresses, differing talents and varying levels of athletic ability will hope to experience their preferred conditions at some stage, thereby getting that extra bit of confidence to bring success within their reach. It’s a fascinating scenario, and W M Nixon tries to set this unique event in perspective.

When the founding fathers of modern dinghy racing in Ireland set up the Irish Dinghy Racing Association (now the ISA) in 1946, they would have been reasonably confident that the immediate success of their new pillar event, the Helmsman’s Championship of Ireland, gave hope that a contest of this stature would still be healthily in being, and still run on a keenly-followed annual basis, nearly seventy years later.

They might even have been able to envisage that it would have been re-named the All-Ireland Championship, even if their original title of Helmsman’s Championship had a totally unique and clearly recognisable quality, for they’d have accepted its fairly harmless gender bias was going to create increasing friction with the Politically Correct brigade.

The Stag at Bay? Anthony O’leary sniffs the breeze last weekend, in charge of racing in the CH Marine Autumn league. This weekend he defends his All-Ireland title in Dun Laoghaire. Photo: Robert Bateman

The Stag at Bay? Anthony O’leary sniffs the breeze last weekend, in charge of racing in the CH Marine Autumn league. This weekend he defends his All-Ireland title in Dun Laoghaire. Photo: Robert Bateman

Sailing should be fun, and run with courtesy – invitation to enjoyable racing, as displayed last weekend in Cork on Anthony O’Leary’s Committee Boat. Photo: Robert Bateman

Sailing should be fun, and run with courtesy – invitation to enjoyable racing, as displayed last weekend in Cork on Anthony O’Leary’s Committee Boat. Photo: Robert Bateman

But what those pioneering performance dinghy racers in 1946 can scarcely have imagined was that, 69 years later, no less than a quarter of the coveted places in the All-Ireland Championship lineup of 16 sailing stars would be going to helms who have qualified through winning their classes within the Annual National Championship of a thirteen-year-old all-Ireland body known as the Irish Cruiser-Racing Association.

And if you then further informed those great men and women of 1946 that those titles were all won in an absolute humdinger of a four-day big-fleet national championship staged in the thriving sailing centre and Irish gourmet capital of Kinsale, they’d have doubted your sanity. For in the late 1940s, Kinsale had slipped almost totally under the national sailing radar, while the town generally was showing such signs of terminal decline that there was little enough in the way of resources to put any food on any table, let alone think in terms of destination restaurants.

So in tracing the history of this uniquely Irish championship (for it long pre-dates the Endeavour Trophy in England), we have a convenient structure to hold together a manageable narrative of the story of Irish sailboat racing since the end of World War II. Add in the listings of the Irish Cruising Club trophies since the first one was instituted in 1931, then cross-reference this info with such records as the winners of the Round Ireland race and the Dun Laoghaire to Dingle Race, beef it all up with the winners of the national championship of the largest dinghy and inshore keelboat classes, and a comprehensible narrative of our national sailing history emerges.

The veteran X332 Equinox (Ross McDonald) continues to be a force in Irish cruiser-racing, and by winning her class in the ICRA Nationals in Kinsale at the end of June, Equinox is represented in the All Irelands this weekend by helmsman Simon Rattigan. Photo: W M Nixon

The veteran X332 Equinox (Ross McDonald) continues to be a force in Irish cruiser-racing, and by winning her class in the ICRA Nationals in Kinsale at the end of June, Equinox is represented in the All Irelands this weekend by helmsman Simon Rattigan. Photo: W M Nixon

It’s far from perfect, but it’s a defining picture nevertheless, even if it lacks the inside story of the clubs. Be that as it may, in looking at it properly, we get a greater realization that the All-Ireland Helmsman’s Championship (or whatever you’re having yourself) is something very important, something to be cherished and nurtured from year to year.

Of course I’m not suggesting that we should all be out in Dublin Bay today and tomorrow on spectator boats, avidly watching every twist and turn as eight identical boats race their hearts out with a variety of helms calling the shots. Unless you’re in a particular helmsperson’s fan club, it’s really rather boring to watch from end to end, or at least until the conclusion of each stage and then the final races.

This is very much a sport for the “edited highlights”. The reality is that no matter how they try to jazz it up, sailing is primarily of interest only to those actively taking part, or directly engaged in staging each event. When great efforts are made to make it exciting for casual spectators, it costs several mints and results in rich people and highly-resourced teams engaged in costly and often unseemly battles to which genuine sporting sailors cannot really relate at all.

But with its exclusion of Olympic and some High Performance squad members, the All-Ireland in its current form is the quintessence of Irish local and national sailing. It’s almost compulsive for its participants, it provides an extra interest for their supportive clubmates, and in its pleasantly low key way it’s a genuine expression of real Irish sailing, the sailing of L’Irlande profonde.

So of course we agree that it might be more interesting for the bright young people if it was raced in something more trendy like the RS400s if they could find sufficient owners to risk their boats in this particular bear pit. And yes indeed, the ISA Discussion Paper and Helmsmans Guidelines of 2012 did indeed hope that within three years, the All Ireland would be staged in dinghies.

But we have to live in the real world. Sailing really is a sport for life, and some of our best sailors are truly seniors who would be disadvantaged if it was raced in a boat making too many demands on sheer athleticism, for which the unattainable Olympic Finn would be the only true answer.

But in any case, if you watch J/80s racing in a breeze, there’s no doubting the advantage a bit of athletic ability confers, yet the cunning seniors can overcome their lack of suppleness and agility with sheer sailing genius.

While they may be keelboats, in a breeze the J/80s will sail better with some athleticism, as displayed here by Ben Duncan (second left) as he sweeps toward the finish and victory in the 2013 All Irelands at Howth. Photo: Aidan Tarbett

While they may be keelboats, in a breeze the J/80s will sail better with some athleticism, as displayed here by Ben Duncan (second left) as he sweeps toward the finish and victory in the 2013 All Irelands at Howth. Photo: Aidan Tarbett

Yet a spot of sailing genius can offset the adverse effects of advancing years – Anthony O’Leary (right) with Dylan Gannon (left) and Dan O’Grady after snatching victory at the last minute in 2014. Photo: Jonathan Wormald.

Yet a spot of sailing genius can offset the adverse effects of advancing years – Anthony O’Leary (right) with Dylan Gannon (left) and Dan O’Grady after snatching victory at the last minute in 2014. Photo: Jonathan Wormald.

But another reality we have to accept is that Ireland is only just crawling out of the Great Recession. And in that recession, it was the enduring competitiveness of ageing cruiser-racers and the sporting attitude of their owners which kept the national sailing show on the road. Your dyed-in-the-wool dinghy sailor may sneer at the constrictions of seaborn truck-racing. But young sailors who were realists very quickly grasped that if they wanted to get regular sailing with good competition as the Irish economy went into free fall, then they had to hone their skills in making boats with lids, crewed by tough old birds most emphatically not in the first flush of youth, sail very well indeed.

Thus in providing a way for impecunious young people to keep sailing through the recession, ICRA performs a great service for Irish sailing. And the productive interaction between young and old in the ICRA fleets, further enlivened by their different sailing backgrounds, has resulted in a vibrant new type of sailing community where it is regarded as healthily normal to be able to move between dinghies and keelboats and back again.

The final lineup of entries is a remarkable overview of the current Irish racing scene, and if you wonder why the winner of the GP14 British Opens 2015, Shane McCarthy of Greystones, is not representing the GP 14s, the word is he’s unavailable, so his place is taken by Niall Henry of Sligo.

2014 Champion Anthony O'Leary, RCYC

RS400 Alex Barry, Monkstown Bay SC

GP14 Niall Henry ,Sligo Yacht Club

Shannon OD Frank Browne, Lough Ree YC

Flying Fifteen David Gorman, National YC

Squib Fergus O'Kelly, Howth YC

ICRA 1 Roy Darrer, Waterford Sailing Club

Mermaid Patrick, Dillon Rush SC

Laser Std Ronan Cull, Howth YC

SB20 Michael O'Connor, Royal St.George YC

IDRA14 Alan Henry, Sutton DC

RS200 Frank O'Rourke, Greystones SC

ICRA 2 Simon Rattigan, Howth YC

ICRA 4 Cillian Dickson, Howth YC

Ruffian Chris Helme, Royal St.George YC

As a three-person boat with a semi-sportsboat performance, the J/80 is a reasonable compromise between dinghies and keelboats, and the class has the reputation of being fun to sail, which is exactly what’s needed here.

The Sailing Olympics and the ISAF Worlds may be terribly important events for sailing in the international context, but nobody would claim they’re fun events. Equally, though, you wouldn’t dream of suggesting the All-Ireland is no more than a fun event. But it strikes that neat balance between tough sport and sailing enjoyment to make it quite a good expression of the true Irish amateur sailing scene.

Inevitably from time to time it produces a champion whose sailing abilities are so exceptional that it would amount to a betrayal of their personal potential for them not to go professional in some way or other. But fortunately sailing is such a diverse world that two of the outstanding winners of the Helmsman’s Championships of Ireland have managed to make their fulfilled careers as top level professional sailors without losing that magic sense of fun and enjoyment, even though in both cases it has involved leaving Ireland.

Their wins were gained in the classic early Irish Yachting Association scenario of a one design class which functioned on a local basis being able to provide enough reasonably-matched boats to be used for the Helmsman’s, and the three I best remember were when Gordon Maguire won in 1982 on Lough Derg racing Shannon One Designs, then in the 1970s Harold Cudmore won on Lough Neagh racing Flying Fifteens, and in 1970 itself, a very young Robert Dix was winner racing National 18s at Crosshaven.

Gordon Maguire was the classic case of a talented sailor having to get out of Ireland to fulfill himself. His win in 1982 in breezy conditions at Dromineer in Shannon One Designs, with Dave Cummins of Sutton on the mainsheet, was sport at its best, though I doubt that some of the old SODs were ever the better again after the hard driving they received.

Driving force. Gordon Maguire going indecently fast for a Shannon One Design, on his way to winning the Helmsmans Championship of Ireland at Dromineer in 1982. Photo: W M Nixon

Driving force. Gordon Maguire going indecently fast for a Shannon One Design, on his way to winning the Helmsmans Championship of Ireland at Dromineer in 1982. Photo: W M Nixon

Then Gordon spread his wings, and won the Irish Windsurfer Nationals in 1984 - a great year for the Maguires, as his father Neville (himself a winner of the Helmsmans Championship five times) won the ISORA Championship with his Club Shamrock Demelza the same weekend.

But Gordon needed a larger canvas to demonstrate his talents, and in 1991 he was a member of the Irish Southern Cross team in Australia, a series which culminated in the Sydney-Hobart Race. The boat which Maguire was sailing was knocked out in a collision with another boat (it was the other boat’s fault), but Maguire found a new berth as lead helm on the boat Harold Cudmore was skippering for the Hobart Race, and they won that overall.

A man fulfilled, Gordon Maguire at the beginning of his hugely successful linkup with Stephen Ainsworth’s RP 63 Loki

A man fulfilled, Gordon Maguire at the beginning of his hugely successful linkup with Stephen Ainsworth’s RP 63 Loki

And Gordon Magure realized that for his talents, Australia was the place to be. More than twenty years later, he was to get his second Hobart Race overall win in command of Stephen Ainsworth’s RP 63 Loki, and here indeed was a man fulfilled, revelling in a chosen career which would have been unimaginable in Ireland.

Harold Cudmore had gone professional as best he could in 1974, but it was often a lonely and frustrating road in Europe. However, his win of the Half Ton Worlds in Trieste in the Ron Holland-designed, Killian Bushe-built Silver Shamrock in 1976 put his name up in lights, and he has been there ever since, renowned for his ability to make any boat perform to her best. It has been said of him when racing the 19 Metre Mariquita in the lightest conditions, that you could feel him getting an extra ounce of speed out of this big and demanding gaff-rigged classic seemingly by sheer silent will power.

The restored 19 Metre Mariquita is a demanding beast to sail in any conditions…

...but in light airs, Harold Cudmore (standing centre) seems to be able to get her to outsail larger craft by sheer will-power.

A different scene altogether, but still great sport – Harold Cudmore racing the classic Sydney Harbour 18-footer Yendys

A different scene altogether, but still great sport – Harold Cudmore racing the classic Sydney Harbour 18-footer Yendys

But as for Robert Dix’s fabulous win in 1970, while he went on to represent Ireland in the 1976 Olympics in Canada, he has remained a top amateur sailor who is also resolutely grounded in Irish business life (albeit at a rather stratospheric level). But then it could be argued that nothing could ever be better than winning the Helmsmans Championship of Ireland against the cream of Irish sailng when you’re just 17 years old, and doing it all at the mother club, the Royal Cork, as it celebrated its Quarter Millenium.

It was exactly 44 years ago, the weekend of October 3rd-4th 1970, and for Robert Dix it was a family thing, as his brother-in-law Richard Burrows was Number 2 in the three-man setup. They were on a roll, and how. The manner in which things were going their way was shown in an early race when they were in a tacking duel with Harold Cudmore. Coming to the weather mark, Cudmore crossed them on port, but the Dix team had read it to such perfection that by the time he had tacked, they’d shot through the gap with inches to spare and Cudmore couldn’t catch them thereafter.

Decisive moment in the 1970 Helmsman’s Championship. At the weather mark, Harold Cudmore on port is just able to cross Robert Dix on starboard………Photo W M Nixon

……but Dix is able to shoot through the gap as Cudmore tacks…..Photo: W M Nixon

……but Dix is able to shoot through the gap as Cudmore tacks…..Photo: W M Nixon

…..and is on his way to a win which will count well towards his overall victory over Cudmore by 0.4 points. Photo: W M Nixon

…..and is on his way to a win which will count well towards his overall victory over Cudmore by 0.4 points. Photo: W M Nixon

Admittedly both Harold Cudmore and the equally-renowned Somers Payne had gear problems, but even allowing for that, the 17-year-old Robert Dix from Malahide was the star of the show, and the final points of Robert Dix 9.5 and Harold Cudmore 9.9 for the 1970 Helmsman’s Championship of Ireland says it all, and it says it as clearly now as it did then.

The six finalists in the 1970 Helmsman’s Championship were (left to right) Michael O’Rahilly Dun Laoghaire), Somers Payne (Cork), Harold Cudmore (Cork), Owen Delany (Dun Laoghaire), Maurice Butler (Ballyholme, champion 1969) and Robert Dix (Malahide), at 17 the youngest title holder ever. Photo: W M Nixon

Local Sailing Class Success Takes Good Boats, But Even Better People

As we near the end of the traditional sailing season, inevitably there’ll be heart-searching among boat owners as to the success and value obtained from their summer afloat – can they really justify the expense of continuing to keep a boat? And with so many imponderables in our sport after a summer which was decidedly mixed in its weather - to say the least - the larger sailing community will be scrutinising those classes which seem to be barely hanging in, those classes which are doing quite well, and those few classes which are spectacularly successful. W M Nixon takes a look at the International Dragons in Glandore, the Flying Fifteens in Dun Laoghaire, and the Puppeteer 22s in Howth to try and find that magic Ingredient X which helps - or has helped - these three very different examples to stay ahead of the game.

The wish to own a boat is a vocation, a calling, a quasi-religious emotional endeavour. It’s all very well for high-flown consultants to tell us that if sailing is going to have general appeal and expand, then publicly-accessed freely-available try-a-sail boats will have to be based at every major club. But dedicated sailors know that what comes easy, goes easy. A spell of bad weather, and your jolly public groups who turned up in droves for a bit of free fun afloat will disappear like the will-o’-the-wisps they were in the first place, seeking instead to find somewhere warm and bright and out of the rain and readily providing the latest novel form of entertainment.

Meanwhile, those who are dyed-in-the-wool boat addicts will have barely noticed the idly-interested strangers coming and going. For whatever the weather, they’ve a boat to maintain, gear to repair, a crew to keep together, and some sensible purpose to find in order to give it all deeper meaning. For they know that unless they’ve a boat and her problems and possibilities occupying a significant part of their mind, they’re going to lose the plot completely.

Nevertheless, in the huge spectrum of boat ownership and sailing classes, why is there so much difference in the successful buzz created by some classes at certain localities, as opposed to the dull and declining murmur emanating from classes which are clearly on the way out?

After all, there are very few utterly awful boats afloat. No boat is completely perfect, though some may seem less imperfect than others. But in today’s throwaway world, if some class of boat is not a reasonably good representative of her general type, then she’ll never make the grade in the first place. And even in times past when news and views moved more slowly, the word soon got around if some much-touted type of boat was in truth a woofer.

Flying Fifteens provide the best of sport in a very manageable two-man package

The perfect harbour for vintage International Dragons – Glandore, with a goodly selection of classics in port, and Dragons of all ages dotted among them

That said, boat-owning is such an all-consuming passion that once a sailor has finally (or indeed hastily) committed to a particular boat type, then he or she will tend to be absurdly dismissive of any remotely comparable craft. But in the last analysis, the desire to own a boat is irrational. So we shouldn’t be surprised that once the decision is made, irrational attitudes manifest themselves in every direction.

And anyway, as John Maynard Keynes once remarked in a totally different context, in the last analysis we are all dead. So in the meantime, it behoves us to get as much reasonable enjoyment out of life as possible. Thus if owning and sailing a boat is your way of obtaining pleasure without harming anyone else, then good luck to you and me, and let’s look together at boat classes which are doing the business.

In considering the International Dragons in Glandore, the International Flying Fifteens in Dun Laoghaire, and the emphatically not-international Puppeteer 22s in Howth, we are indeed casting the net wide, for really they couldn’t be more different. The 29ft International Dragon originated in the late 1920s from the design board of Johan Anker of Norway, and she has become a by-word for Scandinavian elegance in yacht design, but today she’s totally a racing machine and has strayed far from her original concept as a weekend cruiser for sheltered waters.

Golden days of classic Dragon racing at Glandore

As for the Flying Fifteen, they originated from designer Uffa Fox having a brainstorm in 1947, in that he took the underwater hull section of the renowned International 14 dinghy in which he was something of a master both as designer and sailor, but above the waterline he drew out the bow to an elegant curved stem, then he lengthened the gentle counter lines to finish in a long sawn-off transom. That done, he added a little hyper-hydrodynamic bulb ballast keel which seemed very trendy, but in truth it’s severely lacking in useful lateral resistance. Nevertheless it gives the boat the reassuring feel of being a small keelboat rather than a big dinghy, and atop it all he put the rig of an International 14 dinghy of that era.

The clean lines of a modern Flying Fifteen fleet. Try to imagine that within each hull there’s an International 14 dinghy, and above it is the original rig

The result was a boat which is really only useful for racing, and it is a design so much of its times that it’s said that many years later the designer himself tried to disown it. But the owners would have nothing to do with this, they liked the compact and very manageable racing-only package which the Flying Fifteen provides, and these days the class has an interesting world spread, and an attractive policy of staging their World Championships at agreeable sunshine destinations where – thanks to their guaranteed ability to turn up with a fleet of viable size – they can arrange block discounts to provide the owners with a very appealing package.

After the sheer internationality of the Dragons and the Flying Fifteens, the Puppeteer 22s are something of a culture shock, as almost every one in existence has ended up based in Howth, where they have such a busy club programme that they only very seldom go south of the Baily, though they do have one annual adventure to Malahide for the Gibney Classic, and once a year they take part in the historic Lambay Race. But otherwise, they’re totally and intensely focused on club racing off Howth.

The Puppeteer 22s seldom stray far from their home port of Howth, for at home they get superbly close racing with a fleet of up to 26 boats in evening racing. This is former ISA President Neil Murphy racing hard at the helm of Yellow Peril, neck and neck with Alan Pearson’s Trick or Treat. Photo: W M Nixon

They were designed by Chris Boyd of Strangford Lough in the mid 1970s to be fractionally-rigged mini-offshore racers, and in all about thirty-three of the Puppeteer 22s were built by C & S Boyd in Killyleagh (Sarah was Chris’s wife). For a while it looked as though they might take off as a semi-offshore One Design class in the north, but somehow they began to trickle down to Howth. They appealed to those sailors who felt that the alternative of a Ruffian 23 with her huge masthead spinnaker was a little too demanding on crews, whereas the Puppeteer’s fractional rig is fairly easily managed. And today the class in Howth is in such good health that even in the poor weather of 2015 they were obtaining regular midweek evening racing best turnouts of up to 26 boats.

Obviously the Puppeteer 22s are now very much a completely localised phenomenom. But while the Flying Fifteens in Dun Laoghaire and the Dragons in Glandore may be representatives of well-established international classes, the fact is in both cases their neighbourhood success is largely due to a distinct local flavour driven by individual enthusiasm. And in Glandore while it’s recognized that the vintage Dragon class was started by Kieran and Don O’Donohue with the classics Pan and Fafner, the man who beats the drum these days for the racing at Glandore as providing “the best and cheapest Dragon racing in the world” is the inimitable Don Street.

Most people will expect that they will be slightly older than the boats they own, and the older you get the greater you’d expect the age gap to be. But Don’s classic Dragon Gypsy is 82 years old. Yet Don himself manages to be that proper little bit senior to her, as he’s 85 and still full of whatever and vinegar, as they’d say in his native New England.

The one and only Don Street in his beloved Glandore. His International Dragon Gypsy is 82 years old, but he still manages to be the senior partner at 85.

Conditions are pleasantly sheltered for the Dragons in Glandore Harbour, but when the fleet goes offshore – as seen here for last year’s championship - they can find all the breeze and lively sea they might want, and more.

The things that Don has done with Gypsy – between intervals of the renowned ocean voyaging with his 1905-built yawl Iolaire which he has now sold – are remarkable, as he sailed Gypsy from Glandore to the classic regatta in Brittany, which is a prodigious offshore passage for an open cockpit racing boat along what the rest of the world would see as significant portions of the most exposed parts of the Fastnet Race course.

Yet although he did such wonderful business with Gypsy on great waters, he has no doubt that the secret of Glandore Dragon racing’s local success is the sheer nearness and convenience of it all. “Down to the pier and out to the boat in five minutes, the starting line is right there, and we don’t race those boring windward-leewards, rather we use club buoys, government navigation marks, islands - and lots of rocks……”

His argument is that with lovely Glandore Harbour being such an fascinating piece of sailing water, part of the interest in keeping up the pace in a local class lies in using those local features, rather than pretending they simply don’t exist by setting courses clear of the land. But of course when the Glandore fleet – which continues as a mix of classic wooden and glassfibre boats – hosts a major event such as last year’s Nationals – which was won by Andrew Craig of Dun Laoghaire in Chimaera – then the courses are set in open water, and they’d some spectacular sailing with it.

In many ways Glandore is a special case, as the population swells in summer with people coming for extended vacations. When that’s the case, their commitment to local Dragon racing can be total, and not least of the occasional local summertime alumni is the great Lawrie Smith. He may have won the Dragon Gold Cup from a fleet of 66 boats last month in Germany under the burgee of another club, but when he’s racing Dragons in Ireland, he’s emphatically under the colours of Glandore Harbour Yacht Club.

Despite these glamorous international links, it’s the folk on the home ground with their dedication to the Dragon Class in Glandore who keep it all going, and it’s Don Street with his dogged determination to prove you can run a Dragon out of pocket money, regardless of the megabucks some might be ready to splash out, which gives the Glandore Dragons that extra something. And in the end it’s all about people, and shared enthusiasm. If you’ve a warm feeling about the Dragon class, and particularly for classic boats in it, then you know that in Glandore you’ll find fellow enthusiasts and every encouragement.

But up in Dun Laoghaire, if you take a look over the granite wall on to the east boat park at the National Yacht Club in summer, and see there the serried ranks of apparently totally identical Flying Fifteens all neatly lined up on their trailers, you could be forgiven for thinking it’s all just ever so slightly clinical, and certainly distinctly impersonal.

Just about as one design as they could be – the fine fleet at last weekend’s Flying Fifteen Irish Championship in Dublin Bay showed the vigour of the class, which has 47 ranked helmsmen in this country.

Yet you couldn’t be more utterly wrong. Today’s Flying Fifteens may have been technically refined to the ultimate degree to give maximum sport for the minimum of hassle. But their current runaway success – they’re far and away the biggest keelboat One Design class in Dublin Bay – is down to a friendly and very active local class association, and its readiness to reach out the hand of friendship and encouragement to anyone who might be thinking of joining the class’s ranks.

Recently the pace has been set by class captain Ronan Beirne, who recognises that simply announcing and advertising an event is not enough. You have to chivvy people and encourage them into their sailing – particularly after a summer remembered as having had bad weather – and then far from sitting back and smugly counting numbers, you have to keep at it, seeing that crewing gaps are filled, and that those on the fringes are brought to the centre.

The Flying Fifteens – which are essentially a National YC class – offer exceptional value and a very manageable package. The boats are dry-sailed in their road trailers, and instead of queuing for a crane, they have a rapid rota of slip-launching, with the expectation of renewing the wheel bearings each year. Salt water and road trailers are not good partners, but in order to ensure the most efficient launching and retrieval of the boats after each day’s racing, replacing wheel bearings has become something of an art.

The class in Dun Laoghaire secured good sponsorship from Mitsubishi Motors at the beginning of the year, and the sponsors in turn have been rewarded by a thriving class in which inter-personal friendships have developed to such a healthy state that you might find people crewing for someone who would be a complete and untouchable rival at other times in many other classes, but in the Dun Laoghaire Flying Fifteens he’s a fellow enthusiast who happens to be short of a crew on that day.

One of the enthusiastic newcomers to the class this year is Brian O’Neill, who originally hailed from Malahide and was best known for campaigning the family’s Impala 28 Wild Mustard with great success for several years, but now he’s very much a family man living in Dun Laoghaire with three growing kids, and sailing had gone on to the back burner.

Charlie O’Neill (aged 7) at Strangford SC with dad Brian’s newly acquired Flying Fifteen. Under the rapid moving launching system at the National YC, the dry-sailed Flying Fifteens use their road trailers to get the boats afloat in record time. The need for regular replacement of the wheel bearings is allowed for in each boat’s budget. Photo: Brian O’Neill

But as the National YC is just down the road from where he lives, he was drawn into its welcoming ambience, and soon became aware of the attractive and friendly package offered within the club by the Flying Fifteens. He bought one in good order from an owner at Strangford Sailing Club in the Spring, and was soon in the midst of it. Yet it takes up only a very manageable amount of his time, it simply couldn’t be more convenient, and the people are just great too.

Who knows, but having won the class’s last evening race of the 2015 season, he might even be prepared to travel to maybe one event at another venue in Ireland. But the primary attraction continues to be the class’s strong local ethos and ready racing at the National, the friendliness of fellow Flying Fifteen sailors, and the sheer manageability of the whole thing – this is not a boat where the ownership gets on top of you.

If you want to get the flavour of Dun Laoghaire Flying Fifteen racing, you get a heightened sense of it from the report in Afloat.ie of how David Gorman and Chris Doorly won last weekend’s Irish championship in classic style, and if this isn’t good value in sailing and personal boat ownership, then I don’t know what is.

Across Dublin Bay in those misty waters of Fingal beyond the Baily, your correspondent found himself reporting aboard Alan “Algy” Pearson’s Puppeteer 22 Trick or Treat last Saturday for the opening race of the MSL Park Motors Autumn League. I did so with some trepidation, for Alan has a super young crew recruited from Sutton Dinghy Club in the form of GP14 ace Alan Blay, Ryan Sinnott and Claud Mollard, but our cheerful skipper said that as the day was brisk, they needed the fifth on board for ballast.

In fact, I’d only once raced a Puppeteer before, in the lightest of winds when somehow we managed a win. But as this race progressed with the skipper and his young tacticians making a perfect call for the long beat in a good long course which made full use of the splendid sailing waters north of Howth, by the last leg after many place changes it looked as though another win might be on the cards.

Action stations. Puppeteer 22s closing in for their start. Photo: W M Nixon

At mid-race, Gold Dust led narrowly from Yellow Peril, but by the start of the last beat, Trick or Treat was leading from Gold Dust with Yellow Peril third. Photo: W M Nixon

In the MSL Park Motors Autumn League, the mix of classes can sometimes make for interesting situations. Having out-gybed Gold Dust, Yellow Peril is ploughing towards some biggies on another course altogether, and meanwhile there’s the inevitable lobster pot lurking on the way with just one tiny white marker buoy. Photo: W M Nixon

Algy Pearson’s Trick or Treat giving Yellow Peril a hard time to snatch the lead, which she then increased with a cleverly-read long beat. Photo: W M Nixon

But the pace in the Puppeteers is ferocious, and though we’d got a bit of a gap between Trick and former IDRA 14 empress Scorie Walls in Gold Dust, one sneeze from us and Gold Dust would pounce, and alas - we sneezed.

As long as we were carrying the no 2 headsail (what I’d call the working jib) we were level pegging with the formidable Walls-Browne team. But Gold Dust has a lovely new suit of sails (nice ones, Prof), and when the easing wind meant we’d to change up to the genoa, it emerged as a sail of a certain age, and having it set sapped our confidence.

It looked for a while as though Gold Dust (254) had been put fairly comfortably astern……..Photo: W M Nixon

……but an easing of the wind saw Gold Dust finding new speed, and with perfect tactics she was right there with just a hundred metres to go to the finish. Photo: W M Nixon

Until then, the boat had been sailed magnificently, tactics right, trim right, and throwing gybes with such style that the downwind pace never missed a beat. But trying to get that genoa right was a mild distraction, so when Scorie the Queen of the Nile came round the final mark to chase us up the last beat to weather Ireland’s Eye, we’d failed to throw a precautionary tack to keep a loose cover, and suddenly as she rounded she found a local favourable but brief shift of 15 to 20 degrees, and then it was all to play for.

Dissecting it all afterwards (you’ll gather it was a post mortem), we could see two places where we might have still saved the day, but we didn’t grab them, or maybe in truth they were beyond our reach. Whatever, Gold Dust was in the groove and we weren’t. Madam beat us by three seconds. But the banter afterwards and the evidence that Puppeteer people – owners and crews alike – move happily among boats to keep turnout numbers up, was ample proof that here was another truly community based class which perfectly meets a strong local need.

That winning feeling…..Gold Dust’s crew relax after taking first by three seconds. Photo: W M Nixon

The Howth experience. Howth YC Commodore Brian Turvey heads back to port after racing the MSL Autumn League with the Howth 17 Isobel which he co-owns with his brother Conor. Photo: W M Nixon

It had been a great day’s sport, and the Puppeteers being of an age and regularly turning out to race together, they run both a scratch and a handicap system, which is a great improver of local classes – after all, where would golf be without handicaps?

It shows how well Gold Dust has been going this year that her rating is such that we beat her on handicap by one minute and 19 seconds, but we in turn, having been second on scratch, were fourth on handicap, where the winner was the O’Reilly/McDyer team with Geppeto.

Forty years after they first appeared, the Puppeteer 22s are giving better sport than ever, but in a very local context rather than on the bigger stage that might have been anticipated. Yet for their current owners, they do the business and then some. For most folk, this is sailing as it should be. And as to this longterm success of classes which continue to thrive whether they come from a local, national or international background, certainly the quality of the boats is important to some extent. But mostly, it’s the people involved, and their realization that you’ll only get as much out of sailing as you put into it.

A super crew. Aboard Trick or Treat after racing are (left to right) Alan Blay, Ryan Sinnott, Alan Pearson and Claud Mollard. Photo: W M Nixon

Local man, local boat. Algy Pearson with his Puppeteer 22 Trick or Treat. The Pearsons have been sailng from Howth for three generations. Photo: W M Nixon

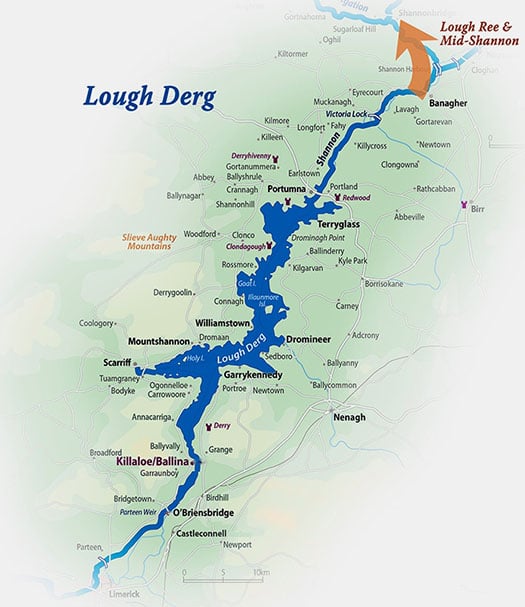

Hire A Cruiser on Lough Derg & Explore the Shannon In Autumn

Ireland is a country of seaways, and waterways which are dominated by the majestic River Shannon. On our island, you can never be more than sixty miles from the nearest navigable bit of sea. Add in the myriad of inland waterways – whether canals, rivers, or lakes – and you have an enthusiastically watery country where it is possible for everyone to have a floating boat berth of some kind within an hour’s journey – and usually much less – from their home.

Afloat.ie’s W M Nixon has been cruising our inland waterways in detail for longer than he cares to admit, though he will concede his first venture on fresh water was in command of a 14ft clinker-built sailing dinghy with a tent, a cruise which took place well back into the depths of the previous millennium. But it’s an experience you’ll always wish to repeat as often as possible, and just last week he found himself going again to the waters and the wild, with a family cruise of three generations on the River Shannon’s great inland sea of Lough Derg.

Journeying westward to join the good ship Slaney Shannon Star at Portumna on the frontiers of Connacht, the car radio was warbling on about the poor weather, and wondering why in England they persist in having their final summer Bank Holiday on the very last weekend of August, instead of having it earlier when the chances of good weather must be better.

As it happens, we know that the chances of good weather at any time in the summer of 2015 were slim enough, though it was briefly present just now and again. Be that as it may, the reasons for taking your “summer holiday” as late as possible in the season seem obvious. Even in this era of flexi-time and working from home and project outsourcing or whatever, the idea of clearly-defined work time and holiday time are still ingrained in us. And of all our traditional holidays, surely it is the summer holiday which is the most avidly anticipated?

Anticipation is usually the keenest and often the best part of any supposedly enjoyable experience. And it’s an altogether more positive and youthful emotion than nostalgia, which soon reeks of sweet decay. Thus the later in the summer you can locate your summer holiday, the longer is the enthusiastic anticipation. So when we got an invitation early in the Spring for some days of family cruising on a fine big Shannon hire cruiser on the magnificent inland sea of Lough Derg in the last week of August, we leapt at it.

Yet let’s face it, it’s something of which you’d be very chary were the planned cruise on the sea, even down in our own lovely West Cork. They may have started the Fastnet Race this year as late in the season as 16th August but, as the late great Tom Crosbie of Cork Harbour was wont to observe, no prudent navigator would really want to have his beloved boat west of the Old Head of Kinsale after August 15th.

However, thanks to Ireland’s wonderful inland waterways, and the mighty Shannon and Erne river systems in particular, we have an all-seasons cruising ground sufficiently varied for even the saltiest sea sailor when summer is gone. And in that last precious week of August – when just one balmy moment of a late summer’s evening is worth ten such in June – you get the perfect combination for a refreshing break from routine and a thoroughly good time with it, with the country looking its lushest best, a marked contrast to spring when it is raw and bare.

Not least of the attractions of a three generations cruise is that the duties of the grandparents and grandchildren are simply to have a good time. It’s the middle generation who are there to provide planning and management. So apart from simply turning up in Portumna at the required time on a Tuesday afternoon, our only task was to get a proper lifejacket for Pippa the Pup, who isn’t really a pup, she’s a three-year-old miniature Jack Russell terrier, but there’s still a lot of the puppy in her. As it was the only job we’d to do, it got huge attention, but thanks to CH Marine’s crisp online service, Pippa had her new outfit many weeks before joining the boat, and almost immediately she realized that wearing the lifejacket was all about having a good time, so no problem there.

Our little skipper - Pippa with her new lifejacket. Photo: W M Nixon

We eased ourselves gently into the Shannon pace by stopping off from the journey westward in Nenagh for lunch at Country Choice, Peter & Mary Ward’s wonderful little food emporium. They don’t so describe it themselves, but “emporium” is the only word to describe a miniature Aladdin’s cave of goodies and wonderful food. This energetic couple were in something of a state of excitement, as the entire Ward operation had just received the word that they were short-listed for an award in the “Best Shops in Ireland” competition, the announcements to be made that weekend.

So it gave us something more to anticipate as we cruised Lough Derg during the following five days, for although much of our mini-voyaging was done along the luxuriant “Tipperary Riviera”, the fact that Tipperary provides some of the best agricultural produce in Ireland does not necessarily mean that it’s a county of foodies. On the contrary, at times the Tip cuisine is very basic indeed, ignoring some of the region’s finest specialities. So Country Choice in Nenagh and the Wards’ famous and enormous stall at the weekly display on Saturdays in the Milk Market in Limerick are beacons of hope and places of cheerful pilgrimage for those who think we Irish could make better use of our wonderful natural local produce.

Portumna at the north end of Lough Derg is a strategically vital crossing of the Shannon – the next bridge is well to the north at Banagher – so inevitably Portumna is a workaday, strung out sort of town with a decidedly utilitarian air to its hire cruiser base at the evocatively-named Connaught Harbour. But the word is that Waterways Ireland have some worthwhile plans to upgrade the entire Portumna-Shannon-Lough Derg interface, though it won’t include replacing the swing bridge which takes the main road across the wide river. Our skipper was already devising a cunning scheme to deal with the dictatorship of the bridge’s opening times even as we were arriving aboard and exchanging a hurried hullo and goodbye with the previous generation on the distaff side, who had cruised with son-in-law, daughter and grandchildren up to Lough Ree.

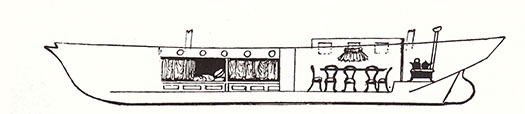

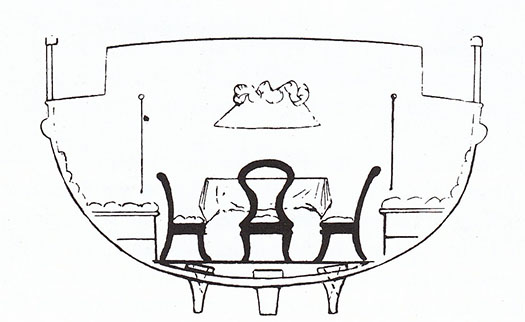

The vessel at the centre of this hectic multi-family interchange was the 42ft Slaney Shannon Star, a fine old workhorse which has been giving sterling service to Emerald Star Line clients for more than two decades. In fact, the Shannon Star Class is quintessential Emerald Star, as just 15 of them were built by Broom’s of Norfolk, and they were exclusively for the Irish company, which worked closely on the design and specification to produce the perfect boat for Shannon cruising. This creative combination produced a comfortable and practical non-nonsense layout, with a straightforward finish which doesn’t pretend to be anything unnecessarily fancy, and a useful big Perkins 76hp diesel which gives the very able and “lakeworthy” hull a cruising speed of 7 knots.

Slaney Shannon Star in the Castle Harbour at Portumna, ensign up and ready to go. Photo: W M Nixon

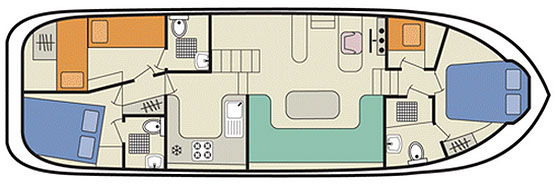

This layout plan gives the broad outline of the Shannon Star’s very effective accommodation, but the forward cabin is roomier than shown, with proper gap to open the door fully.

Within this package, as the layout plan shows there is comfortable accommodation for six without using the settee berths in the saloon, there’s also an extra berth in its own little cabin just under the in-saloon steering position (it became Pippa’s cabin when we were ashore to dine), and while steering from the inside position is very comfortable with good visibility, the flybridge offers splendid views and is sufficiently large to be sociable with it.

Those who sailed with our son David when he was campaigning the likes of the Corby 36 Rosie (now Rockall III) and other offshore racing machines a decade ago will know that he thrives on planning and execution, while his wife Karen is more than a match for him. Thus for Georgina and Pippa and me and Matthew (aged 6) and Julia (aka The Diva) age 3, it was just case of being here and going with the flow and being prepared for enjoyment, for there was a lot of that.

David’s plan for the first evening in Portumna was typical of the man. They’d spent a fair bit of the day completing the final stage of the long passage down-Shannon from Lough Ree, so time ashore in a hospitable environment with food available was the target. He came up with the scheme that we’d go for supper at the very characterful Ferry Inn just across the river. But before that, we’d take the boat through the swing bridge at the 7.45pm opening, and berth her at the pontoon immediately below the bridge, which would shorten the walk to the inn, and also make it free choice for departure time in the morning.

But this was only the beginning of the man’s ingenuity. Supper was well under way in the pub when he suggested that if the senior men didn’t linger too long over the puddings, they could use the last of the daylight to take the boat the mile or so to the little harbour at Portumna Castle, while the women and children – by now immersed in various electronic games and slow eating – could follow when ready by taxi.

We wanted a characterful pub with good food to start the cruise, and we found it at the Ferry Inn beside Portumna Bridge. Photo: W M Nixon

Sounds crazy, but it was a move of genius, for the berth beside the bridge is noisy with the road traffic and doesn’t give a sense of being away from it all, whereas the tiny harbour at the castle is pure holiday setting. The only fly in the ointment of this perfect plan was that as we approached the little harbour in the very last of the daylight, it was to find the entrance well-filled with a Shannon barge, but somehow we squeezed our 4.1 m (13ft 6ins) beam in past, and then there was just one space left in the most sheltered corner of this attractive mini-port to provide Slaney Shannon Star with a sweet berth for the first night of the cruise, and a warm wecome for the rest of the crew when they arrived in their own good time.

We’re no strangers to three-generational family holidays, but have less experience of three-generational lake cruising, and of course as the kids are growing up so quickly, the requirements vary from year to year. So in the morning sunshine, while the senior adults with an energetic little dog might have felt like no more than a walk in Portumna Forest Park, the parents with children had to seek out a proper children’s playground, but a skillful combination of plans saw all wishes in the walkies department being well met.

It has to be said that Portumna is definitely tops in at least one department. The Children’s Playground - it’s between the castle and the town - is world class, a creation of Cavanagh’s of Roscrea. They were established way back in 1806. But I doubt if their metal-working skills were being deployed for children’s playgrounds when the company came into being while Napoleon was still strutting his stuff around Europe, so all power to Cavanagh’s of Roscrea for adaptability.

The children’s playground at Portumna. Built by a company founded in 1806, it’s a wonder to behold. Photo: W M Nixon

As for Portumna Castle…..well, if you find your household heating bills depressing, cheer yourself up with the thought of the effort it seems to have taken to heat Portumna Castle. You’ll seldom see chimneys on this scale – it must have taken all the turf out of an entire raised bog eevry winter to heat this massive pile.

Portumna Castle – the mighty chimneys suggest even mightier heating bills. Photo: W M Nixon

Home sweet home, but far from the Baltic Sea – Triskel and her live-aboard skipper. Photo: W M Nixon

By complete contrast, back at the Castle Harbour we met up with a Polish sailor who had cruised the Baltic before he set off to start life anew in Ireland eleven years ago, and when he discovered the Shannon and all its attractions he moved aboard a little sailing cruiser eight years ago. He has lived on her ever since, in and around the Shannon lakes, and is well content, though when I guessed his boat might be an Anderson of some sort, he was very positive in making sure that I realized his beloved Triskel was an Anderson 22 Mark 2, and not one of the inferior original Mark 1 versions.

Having been bemused by contemplating the heating bills for Portumna Castle, I didn’t find out his name before he headed out of port, but by this time our skipper also reckoned it was time to go. David had an app which gave weather predictions so accurately that he could tell you exactly when the rain would fall on different parts of the lake, precisely how big the rain-drops would be, how long they’d be falling, and how much wind would be in the midst of them. Or so it seemed to the rest of us. But somehow he got us all moving together aboard ship out of Portumna Castle Harbour at morning coffee time, and we proceeded southwards down the splendid lake almost entirely in sunshine as big dark rain squalls ran north along the Atlantic seaboard to the west, while over to the east it was pitch black over mid-Tipperary and they’d some flooding. Yet aboard Slaney Shannon Star, this helmsman on the flybridge managed to get a bit of a suntan during the two hours plus passage down to Mountshannon.

From the lake, you get glimpses of other’s people’s little bits of paradise – this mini-port is one of the East Clare shore north of Mountshannon. Photo: W M Nixon

Lough Derg is 40 kilometres long (it’s 23 land miles in old money from Killaloe Bridge to Portumna Bridge) and around 20 kilometres across its widest part, but it follows the contours as befits a developing river valley to provide a handsome convoluted lake. While the coastal scenery is fairly flat up about Portumna, as you get south past Dromineer the land is rising to port and particularly to starboard, with the final approaches to Killaloe between the Arra Mountains and Slieve Bernagh becoming quite spectacular.

In classic cruising style, our skipper had decided the best way to deal with the lake was to get down to Killaloe on the first day, and then cruise back to Portumna at a much more leisurely pace. But even when you’re trying to log the miles, Lough Derg offers ample choices for quick stops, and as the weather app was talking about some decidedly lively southwest to west breezes later in the afternoon, the logical place for a stopover was Mountshannon.

This would mean that if the top did come off conditions for a while, we’d be located so that we could hold round a weather shore to get a smooth passage into the long “reverse estuary” down to Killaloe. But first, we’d to enjoy Mountshannon. It’s headquarters of the Iniscealtra Sailing Club (Iniscealtra is the neighbouring holy island, complete with Round Tower and a place of pilgrimage), but Mountshannon has the additional advantage of being serenely south-facing over a fine but sheltered bay, and it is home to an impressive fleet of yachts lying in a classic anchorage. There are the likes of Hallberg Rassys among them, and if you wondered what on earth a Hallberg Rassy ocean cruiser is doing on a lake, we suggest you get to Mountshannon and understanding will come.

An anchorage for proper yachts – some impressive craft are lying to moorings in Mountshannon. Photo: W M Nixon

We meanwhile understood that rain was coming, and fast, so after a neat bit of berthing even if I do say so myself, we nipped up to the village inn and took aboard broth and stews while the rain battered the street outside, and German and English visitors supped their pints of Guinness with that happily bemused little smile you’ll see on the faces of tourists who have discovered an Irish inn exactly as they hoped it would be, including the rain outside.

But even that cleared on cue, and we needs must visit Mountshannon’s unique attraction, the combined labyrinth and maze. A perfect opportunity for junior scouts to guide the oldies about. However, the wind had come through as expected, so much so that Mountshannon’s famous white-tailed sea eagles appeared to be grounded for the afternoon. But though Slaney Shannon Star was sitting serenely in a wellnigh perfect berth for a stormy night, the menfolk were just too interested in seeing how she’d perform in a real breeze of wind, with a bit of a sea running, to stay on in the same place.

Slaney Shannon Star snugly berthed at Mountshannon. The front is going through, and the wind has veered, but there’s enough of it to keep the sea eagles of Mountshannon grounded. Photo: W M Nixon

There really is a maze at labyrinth at Mountshannon, but it takes an aerial photo to show them properly

“It’ll only be slightly lumpy for a few minutes” was the mantra. And it has to be said the old girl coped superbly, though fortunately all warps had been lashed in place, as for a little while -until we were feeling the shelter of the Clare coast in under the delightfully-named Ogonnelloe – some quite substantial quantities of Lough Derg were sweeping at speed over the Slaney Shannon Star.

Sea test – Slaney Shannon Star finds a bit of a sea running on the lake. Photo: W M Nixon

For a while, quite a lot of Lough Derg was sweeping over Slaney Shannon Star on passage from Mountshannon to Killaloe, but it didn’t take a feather out of this able boat – those towels are laid out to dry, not to cope with leaks. Photo: W M Nixon

But in the Killaloe estuary, relative peace returned, the black clouds raced away to the east, the sun came out with a rainbow, and there was this sense of approaching somewhere important, heightened by the quality and variety of the lakeside and hillside houses. Some people find this Irish scattering of houses, each in its own little world, to be something of an irritation among some rather fine scenery. But I like it. There’s more than enough empty uninhabitable wilderness in the world, and except for the most spectacular mountains, Irish scenery is enlivened by houses dotted here and there in such a way that you think pleasantly of the agreeable way of life that might be found in them.

The storm squall has passed, and the lush country of the Tipperary shore is seen at its best with a rainbow in the approaches to Killaloe. Photo: W M Nixon

Once we were into the smooth water, Madam got on the phone to suss out the possibilities of an “Objective Achieved” supper at the renowned Cherry Tree on the Ballina side of Killaloe, and of course chef patron Harry McKeown himself answered the phone and recognized her voice immediately. But he went through the formality of booking a table for six in impersonal style before letting her know her cover was blown.

Whatever about Georgina’s problems in dining anonymously, for the rest of us it made for a idyllic evening, with the boat berthed as conveniently as possible at the berth generously provided by the Lakeside Hotel, the shortest walk imaginable to the Cherry Tree, a riverside window table to admire a sister-ship berthed directly across the water on the Killaloe side, and food glorious food while the light lingered in a fair approximation of a summer’s evening.

Our first berth at Killaloe was at the hospitable Lakeside Hotel on the Ballina shore. Photo: W M Nixon

Mission accomplished – the team have reached The Cherry Tree for dinner in Killaloe. Photo: W M Nixon

An interest in visiting Killaloe Cathedral in the morning had been expressed, so lo and behold our thoughtful skipper moved the boat across river in the morning on his own while the rest of us were still bestirring ourselves, thereby removing the need to walk across Killaloe’s ancient but much overworked bridge. It suffers from ludicrously excessive traffic – the lovely little riverside town does really urgently need a by-pass and the long-planned new bridge to the south. But St Flannan’s Cathedral well exceeded expectations. It’s of very modest size for anyone expecting a Shannonside version of Chartres or York Minster. But we knew it well from the outside, yet going in was a revelation, a haven of total peace in this Cathedral of the Waterways.

The Cathedral of the Shannon – St Flannan’s at Killaloe is on the banks of the old canal to Limerick which pre-dated the Ardnacrusha development. Photo: W M Nixon

A soothing place - Killaloe Cathedral. Photo: W M Nixon

Busy place - Killaloe is very much the southern capital of the Shannon waterway. Photo: W M Nixon

There seemed to be an unspoken agreement that we weren’t going to break the spell of peace by walking across the bridge, but as this meant the kids couldn’t avail of the playground on the Ballina side, it was a case of up sticks and away from the impressive new Waterways Ireland pontoons on the Killaloe side, and off we went north and east to Garrykennedy with its handy playground, on the way passing learner sailors in action off the University of Limerick’s Activity Centre on the Clare shore, and then – for it was a pleasant sunny sailing day after Wednesday’s weather kerfuffle – we passed a real live sailing cruiser going on her merry way, plus several powercruisers.

With lighter winds, sailing can resume at the University of Limerick Activity Centre near Killaloe. Photo: W M Nixon

Waterside paradise - lakeshore house near Killaloe. Photo: W M Nixon

The guess is it’s a Halcyon 23 enjoying the breeze on Lough Derg – and taking in one’s fenders is optional on the lakes. Photo: W M Nixon

All the little ports about Lough Derg have their own individual character, and Garrykennedy is about as different as possible from Killaloe, which in turn is very different from Mountshannon, while Dromineer – where we were to spend the night – is different again.

But most of the ports popular with today’s sailors on Lough Derg have it in common that once they were part of a busy waterways transport system, each with its own little mini-harbour which could accommodate the barges which might have come all the way from Dublin via the Grand Canal. The cream of the fleet were engaged in the sacred task of conveying Guinness’s Porter from St James’s Gate Brewery all the way to the connoisseurs of Limerick, whose tastes were and are so pernickety that when any variant in any product is contemplated in the Guinness organisation, somebody always wonders how it will do in Limerick…

Garrykennedy’s little harbour was created inshore of the 15th Century castle of the O’Kennedys. Photo: W M Nixon

Larkins of Garrykennedy is one of the most popular food pubs on Ireland’s inland waterways. Photo: W M Nixon

The décor in Larkin’s of Garrykennedy includes this superb half model of a Shannon One Design OD made by Reggie Goodbody of Dromineer. Photo: W M Nixon

So keen is Limerick to get its Guinness that in a storm one winter a canal boat (they were never called barges in their working days) headed out after sheltering in Garrykennedy and sank off Parker Point taking some of her crew down with her, but that’s a sad story for another day. For we got into Garrykenedy on a sunny day to find a handy berth in the old harbour, a good lunch in Larkins, and a classic Children’s Playground with real old-fashioned swings where Matthew and Julia proved fearless.

By the time you’re a day or three into your Waterways holiday, you lose track of time, but I think it was later that afternoon when the Slaney Shannon Star headed in the sunshine across to Dromineer. There, we found the most-sheltered spot at the quayside in the harbour was entirely taken up by a slovenly-berthed J/24 which, if it had been secured in a more thoughtful manner, would have left plenty of room for other boats.

However, the nearest handy berth put us right beside the playground, so bonus points for Dromineer. And then, as we had access to sheltered water, it was time for a bit of fun with the outboard dinghy, which was a winner with the kids, who were soon helming it with skill. You’d expect that of Matthew – he has helmed a Howth Seventeen – but Julia at just three years old was a very cool and quick learner.

The berth at Dromineer was ideal for family cruising, being right beside the children’s playground. Photo: W M Nixon

Outboard dinghy sport at Dromineer. Photo: W M Nixon

Matthew in charge, and The Diva not too pleased. Photo: W M Nixon

The Whiskey Still at Dromineer is a Lough Derg institution. Photo: W M Nixon

An overnight in Dromineer means supper at The Whiskey Still, and very good it was too, a real local which comes pleasantly to life as the evening draws on, and lots of folk to talk to about this intriguing place, which in the great days of Waterways transport, was by way of being the main port for North Tipperary. But since 1835 it has also been the home of Lough Derg YC, whose fine clubhouse was taking a brief rest between the excitements of the annual Lough Derg week and the imminent arrival tomorrow of the international fleet of cruising-racing Wayfarer dinghies.

The last walk of the day for Pippa discovered an energetic game of kayak polo under way off Dromineer’s little beach (yes, they really do have a beach, the immaculately-kept Dromineer has everything) but later that night the breeze freshened again and our fenders were squeaking a bit. We couldn’t be having that at all, so the skipper found us enough room along the other quay for us to warp into a berth where the breeze held us noiselessly off the wall for a night of peace.

Kayak polo at Dromineer. Photo: W M Nixon

Dennis Noonan of Round Ireland race fame on his Pegasus 800 Photo: W M Nixon

By this time we were so totally into Waterways time that I haven’t a clue when we left Dromineer next day, but we seem to have crowded several days of living into a morning. The playground had to be given a thorough work-over, the dinghy had to be taken out for a spin at least twice, then Pippa had her morning walk along to Shannon Sailing’s secluded marina where of all people we met up with the great Dennis Noonan of Wicklow and Round Ireland Race fame. He was aboard his able little Pegasus 800 which is for sale, and is a fine sailing cruiser if you’re interested in a proper yacht with full standing headroom. But there was little enough time to discuss boat sales, for in real life Dennis is a market gardener of long experience, so he and Georgina were immediately at it yakking away about genuine local produce and how to get people to appreciate what their neighbourhood can produce in season.

I meanwhile wandered off meet up with Robbie the Main Man in the workshop, and soon discovered he was the owner of an enormous 95ft boat – the Spera In Deo - which was lying in Dromineer harbour, a former Dutch mussel dredger which he had discovered in a ruinous state in Donegal after a fire. He was able to make her sufficiently seaworthy to bring her south along the Atlantic seaboard and into the Shannon crewed by all the usual gallant suspects, and while he still has much cosmetic work to do to the exterior, he has fitted out the interior in the most extraordinary way to make her the biggest four berth motor-cruiser in the world, as there are two enormous en suite double cabins - one with a Jacuzzi - while the headroom in the vast main saloon is theatrical in scale.

95ft of the biggest four berth motor cruiser on the Shannon – the Spera In Deo at Dromineer. Photo: W M Nixon

To grasp the scale of the Spera In Deo’s interior, you have to realize those are full-height interior doors for a house. Photo: W M Nixon

Eventually I was reunited with my brood in the Lake Café right on the harbour. It’s open from 8.30am until 5.0pm, which makes for a very civilised little village arrangement as The Whiskey Still then opens up for food. Declan & Fiona Collison, who run the Lake Café, used to run The Whiskey Still, so they know the Lough Derg hospitality scene inside out. But like everyone along this ancient waterway, they are as keen to talk about its fascinating past are they are interested in its present and future, and the Lake Café’s walls are adorned with aerial photos of Dromineer from around 1967 which really do bring home to you how much Ireland has moved on during the past half century.

Breakfast in Dromineer – Georgina, Matthew and Julia have the first of the day’s five meals….. Photo: W M Nixon

Dromineer as it was in 1967 – photo courtesy Lake Café.

Heading up-lough in “vivid sunshine”. Photo: W M Nixon