Displaying items by tag: Sailing on Saturday

#classicboat – In the summer of 2014, the RNLI in Crosshaven received an unexpected cheque from an unusual source. As ever with lifeboat fund-raising, it was very welcome. But it's not every day you get €1500 out of the blue from a high fashion magazine like Vogue Netherlands. W M Nixon unravels the tale of how this came about, and ponders the various challenges facing the enthusiasts who try to keep classic boats in full sailing commission.

Once upon a time, on a pure early summer day of clear sunshine in Connemara, the demands of the day job caused us to head up the driveway of one of the pleasantest country house hotels in all Connacht. But the bright mood of the morning was soon dispelled by finding the place full of bad tempered if beautiful people from Italy.

It turned out they were the complete creative team – photographers, models, directors, editors and all – from a leading Milan fashion magazine. They were in Ireland for a long-planned and lengthy photo-shoot of the coming season's trendy tweeds. They'd reckoned the Irish climate would guarantee they'd be up to their ears in ideal conditions to provide moody shots of even moodier models in ultra-fashionable tweeds on an extraordinarily moody bog with unbelievably moody Irish mountains beyond, the whole thing recorded under an uber-moody grey Irish sky.

But for day after day, the sun had shone from a cloudless sky, the breezes blew only very gently from a blue Atlantic, the fabulous range of the Twelve Bens could quite reasonably have been re-named the Twelve Benigns, while the great swathes of bog glowed in friendliness in the sun. Moodiness was out. All was sweetness and light. And the forecast was for more to come.

So after another day of screaming frustration, they upped and left, screeching that they could find more suitable conditions back home, just down the road in the Valley of the Po. Doubtless they could. But back in Connemara everyone simply relaxed and enjoyed it, for the Italians' bill had been paid in full, they maybe could even re-let some of the rooms in the hotel in the few days remaining of the booking, and sure wasn't the weather just wonderful anyway, and had we ever seen the garden looking so well?

If you think fashion people are out on a limb in relation to the rest of us, take time to reflect that for most of humanity, boat people are odd too. Even with the newest craft, we still think of them as living beings, whereas the rest of the world thinks that, regardless of their age, they're no more than vehicles, and uncomfortable, awkward, dangerous and expensive vehicles at that.

Roundstone in Connemara on a gentle day with a sublime view towards the Twelve Bens in the evening sunshine – totally unsuitable conditions for a mood-laden fashion shoot. Photo: W M Nixon

So when you get some sailing person whose pulse is quickened only by classic or traditional boats – anything unusual so long as it is full of character, and preferably old - then you get someone who scores a double negative with the ordinary run of boat-loathing humanity.

And though high fashion may be comprehensible to a larger proportion of mankind than is enthusiasm for old boats, nevertheless it too is still a rather peculiar or at least very specialist interest with which to dominate one's life.

Thus it's just possible that when high fashion and dedicated classic boat fans link up, an unexpected bond can be formed. Certainly it seems to have happened when Vogue Netherlands got together in Crosshaven during the summer for a photo-shoot with Darryl Hughes' superbly-restored 1937 Tyrrell-built 43ft ketch Maybird.

And the successful outcome of it all, with a useful cheque being presented to Crosshaven RNLI afterwards, was a reminder that while boat restoration projects can indeed be brought to a successful conclusion, once the job is done, you then have to move on to the next stage of finding imaginative and useful things for the boat to do, as there's nothing worse for the wellbeing of any boat than doing nothing.

After two good day's work afloat out of Crosshaven, a cheque for €1500 is handed over by Zoe Rosielle of Vogue Netherlands to Patsy Fegan, RNLI Deputy Launch Officer Crosshaven, with Shore Crewmember Robbie O'Riordan in support. Also in the picture are the rest of the Vogue Netherlands team, with three of Maybird's crew – Pat Barrett, Marie Keohane, and Darryl Hughes – top left, while fourth crewmember Joeleen Cronin took this photo

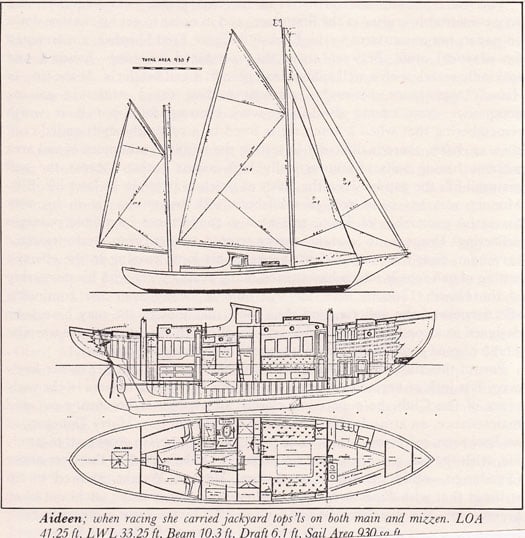

The story of Maybird has been told in snippets here before. She's a very near sister of the 16-ton ketch Aideen which was built by Jack Tyrrell of Arklow in 1934 for Billy Mooney, who in those days was Howth-based, but he later became a leading figure in Dun Laoghaire. Aideen was built to a Fred Shepherd design, but it's said that Shepherd had only been brought in to put manners on numerous very detailed drawings by Billy Mooney himself, including the layout – unusual at the time - of a centre cockpit.

Very conservatively rigged as a gaff ketch, Aideen was no slouch – she won her class in the 1947 Fastnet Race. Soon after, she was sold to Canada, where she was last heard of in 1974. Mooney claimed he'd to sell her because he could no longer afford to buy his crew dinner every time they won a race, and they were winning too often. That was a very Billy Mooney kind of remark, but certainly he almost immediately down-sized to the excellent little 6-ton John Kearney Bermudan yawl Evora of 1936 vintage, and with her he continued winning offshore until, with his retirement from work, he also swallowed the deep sea anchor and took up Dragon racing in Dublin Bay.

Meanwhile, during the mid 1930s an admirer of Aideen had been a keen sailing man originally from Cork, one W C W Hawkes, an officer in the Indian Army who commissioned Maybird, a near sister-ship of Aideen, from the Fred Shepherd-Jack Tyrrell team in 1937. Hawkes retired from India in the late 1930s to live in Restronguet on Falmouth Harbour in southwest England, but he was to have little enough use of Maybird with the intervention of World War II from 1939 to 1945, and his death in the late 1940s.

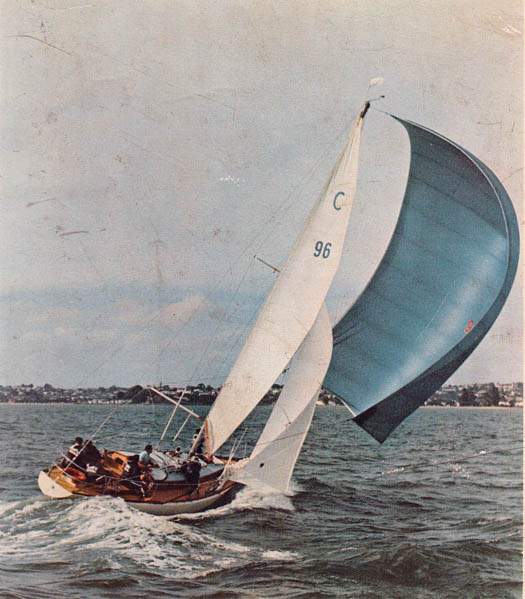

The first-born. Billy Mooney's Aideen was built by Tyrrell's of Arklow in 1934. Her younger sister Maybird, built in 1937, had a slightly longer canoe stern. Maybird's modern accommodation layout is also different, with the galley moved aft to the starboard side at the foot of the companionway

Maybird under her Bermudan rig in the late 1950s. Her restoration has included this rig's replacement by the original gaff configuration for the mainsail.

Subsequently, the 43ft ketch led a varied career, acquiring a Bermudan rig and an RORC rating for racing, and then in 1972 she was sailed out to New Zealand. Darryl Hughes came upon her there in 1990, and was smitten. Quite why some boats speak so eloquently to some people at certain times is sometimes difficult enough to understand, but the great project he has since completed with Maybird suggests that in this case it was the one very special boat for one very special person, and at just the right time.

He comes from a community in North Wales where there was no local tradition of industry or high-powered commerce, yet education at the local grammar school and a degree from Manchester University saw him moving into international companies, and by his thirties he was a rising star in general management in global organisations with a later emphasis on marine electronics.

This in turn fostered his interest in sailing, and he was learning the ropes with his own Nicholson 32 when a working spell in New Zealand led to his first sight of Maybird in the Bay of Islands. By 2007, with an early and well-funded retirement beckoning, he had her shipped back to England with a restoration in mind.

But the quotes he had for the job from established yards were horrendous, so he decided to do it himself as his own Project Manager. Sensibly, it was done in the heart of the English marine industry, where he could call on a diversity of talents to make progress with this project, which was soon well under way in Southampton in a temporary shed he'd created with tarps over a proper scaffolding structure.

The owner-managed restoration project on Maybird under way in the temporary shed in Southampton. Photo: Darryl Hughes

Mission accomplished – the restored Maybird emerges from the project workshop. Photo: Darryl Hughes

His long experience in international industry stood well to him, for the work went steadily ahead, and after two years the restored Maybird emerged as good as new, in fact better. And the project was completed for around a quarter of a million pounds sterling, about half of the most reasonable quote he'd received from the established yacht restoration yards.

For many people, such a restoration would be enough in itself, but Darryl Hughes showed his calibre by progressing on to keep Maybird as active as possible. She was raced in the classics in the 2011 Fastnet, and finished in a slightly better time than that recorded by Aideen in 1947. As well, she has been cruising extensively, sometimes on a semi-commercial charter basis, while also taking part in classic yacht regattas.

When it all becomes worthwhile. The restored Maybird sails again, re-rigged as a gaff ketch to the original design.......

.....and she turns in an encouraging performance, with a better time in the Fastnet Race of 2011 than Aideen had in the Fastnet of 1947.

An underlying theme has been his growing interest in Ireland and things Irish, thus he has based the boat for lengthy periods in Crosshaven while researching the history of the Hawkes family in Cork and in Cork Harbour sailing. But as well he has extensively cruised the Irish coast, and with his developing interest in literature he has twice taken a full part in the Yeats Summer School in Sligo in late July. The new pontoon just below the bridge in Sligo port might have been installed for Maybird's convenience, but Darryl Hughes is still the only person who is known to have sailed to the Yeats School as a matter of course.

In 2011, Maybird returns to her birthplace of Arklow, where she was built in 1937. Photo: W M Nixon

Immaculate workmanship. The beautiful restoration of Maybird's deck and coachroof, seen in Arklow in 2011, contrasts with the rough and ready beer keg pressed into use to aid boarding. Photo: W M Nixon

Currently, Maybird is based in friendly Poolbeg Marina in Dublin Port, and her owner has spread his wings even further with a course of study in Trinity College, while living on the boat and pondering the production of the required 15,000-word dissertation on Irish writing. Last winter, however, was spent in the congenial surroundings of the Salve Marina in Crosshaven, and thanks to that there was the involvement with Vogue Netherlands – we let Darryl take up the story:

"Vogue Netherlands wanted to organise a fashion shoot in SW Ireland, and their location scout came across Maybird wintering at Crosshaven in Cork harbour back in February 2014. I agreed that they could use her as long as they made a contribution to the Crosshaven RNLI station, and the shoot took place in early June over two days.

The entire Vogue contingent consisted of eight people - three models, photographer, photographer's assistant, make-up/hair stylist, wardrobe assistant and overall fashion director, together with three huge suitcases of clothes for the models plus extra camera gear, lenses etc etc. To sail Maybird we had a crew of three plus myself, the other sailors being Pat Barrett, Marie Keohane, and Joeleen Cronin, the daughter of the house in Cronin's pub. As you can imagine, my major concern was the safety of all aboard as the majority were not sailors.

We met the day before onboard and worked out that Maybird's aft cabin would do as the changing area for the models and the huge suitcases were manhandled down the companionway and through the galley. The aft cabin was then transformed into a Vogue changing room/hairdresser's salon. The plethora of laptops, lenses and spare cameras plus the film banks – yes, film, not all that digital malarkey I'm pleased to say- were stowed in the saloon. The saloon became the studio, but we had access to all of Maybird's chart table and instruments if required. Fortunately, all of the chart-table electronics are duplicated in the doghouse, which also has the 15" plotter screen.

The aft cabin, luxurious by the standards of 1937, made for a rather cramped changing room/hairdressers salon during the Vogue Netherlands photoshoot. Photo: W M Nixon

The galley and the chart-table together amidships at the foot of the companionway may seem a tight fit to modern sailors, but it would have seemed the height of comfort to cruising folk in the 1930s. Photo: W M Nixon

Once the stowage was sorted, we agreed that unless people were required on deck they stayed below. Everybody wore life-jackets and the only people that were allowed to take them off were the three models when the camera was rolling. Once the camera was silent the models donned their life-jackets again. We had a support RIB so that the cameraman could take pictures of Maybird sailing, so to an extent we had our own lifeboat with us, but my job was to keep all twelve "crew" on board.

We were blessed with gentle sailing conditions for the first day - wind max F3. The director wanted all Maybird's sails hoisted, and so we agreed set courses to sail. The crew set Maybird up, we chose courses that we could hold for as long a time as depth/traffic/hazards allowed, and then the photographer got to work with the models. We had an excellent rapport with the photographer, who understood that the skipper has the final say, and would stop shooting when we made the call "30 seconds to tack". Each of our legs or boards had to be agreed with the photographer in terms of where the sun was, the effect of shadows, background etc..

One of the models was starting to experience the early stages of sea-sickness as we approached the harbour entrance abeam of Roche's Point lighthouse, so we headed back inshore. Recovery was more or less instantaneous when back in flattish water.

Given the largely clement conditions we were out for some seven hours on the first day. But Day 2 was different. Wind was up to F5 gusting F6 and the sky overcast. The sea state was no longer smooth but more moderate to lumpy. I agreed with the director that we would go out, but we would not put up the mainsail - we would sail with jib, staysail and mizzen. I just wanted to keep things as simple as possible from a sail-handling viewpoint.

The cameraman wore his safety harness as well as his lifejacket as he was leaning over the bowsprit and over guardrails to take many of the shots that day, so I made sure he was clipped on. We agreed the models would not lean over the guardrails or do any poses that could lead to them falling off the boat. For this day, we were only on the water for some three hours.

Interestingly, the only pictures from Day 2 used were a black and white one with the female model standing on the foredeck. The sky really was nasty. No Photoshopping used there!

Despite Maybird's complexity in terms of numbers of sails and ropes, as she has a long keel she will sail on her own and hold her course when the sails are balanced so it was easy for her sailing crew to set her up and then crouch down out of the cameras way whilst the models did their stuff.

Both the photographer and his assistant were sailors back in the Netherlands, so that helped a great deal. The Maybird crew of four for one day, three on the other, really kept an eagle eye on the Vogue crew in terms of safety - that was the challenge, not sailing the boat. We tacked rather than gybed and as I say, when the wind did pick up, we sailed without the main - one of the great advantages of the ketch rig.

We managed to stay out of trouble, so our only dealings with the Crosshaven RNLI was to hand over a cheque to them".

That was only part of the good work done by Maybird in 2014. She was signed on to play a key role in an Irish Coastguard exercise in Dungarvan Bay later in the summer. Then once again the skipper's participation in the Yeats Summer School in Sligo resulted in a round Ireland cruise, with bits of Scotland thrown into the mix. And now she's a study centre in Dublin, helping to absorb the multi-facetted culture of our unique city. Truly, a busy ship is a happy ship.

Maybird as seen from the S&R helicopter during an exercise in Dungarvan Bay. Photo courtesy Irish Coastguard.

Classic Yachts, Traditional Boats, Where's The Truth?

With a Golden Jubilee Regatta being planned for New Zealand in 2015 to celebrate the glory years of the One Ton Cup from 1965 to 1983, W M Nixon ponders on the requirements for a genuine classic yacht or traditional boat, and makes a plea for saving a very special 12 Metre.

It's said there are enough relics of the True Cross to build a full-size replica of Noah's Ark. You'd need to be very clever with the epoxy saturation techniques to do it, as most of the pieces are very small. But apparently it's reckoned the required volume of timber is out there at shrines throughout the world.

This question of ancient or even vintage authenticity arose as soon as last week's blog about the Peel Traditional Boat Weekend appeared. One commentator, while not prepared to put his head above the parapet even under anonymity in the proper comments section, was quick to point out that not only is it obviously not a weekend as it runs from Wednesday night until Monday, but the three awards winners mentioned were clearly not as they seemed.

The lovely little Menai Straits-based schooner Vilma, while evoking memories of the Welsh slate schooners, is no such thing. She started life as a ketch-rigged Danish fishing boat in 1934. As for the startling bisquine-rigged 50-footer Peel Castle from West Cork, we're in Disneyland. She was originally a motorised Penzance fishing boat built in Porthleven in 1929. But after nine years of patient restoration work completed in the Ilen River in West Cork in 2008, this exotically rigged vessel with her three masts fanning every which way sailed happily to Greece where, one would guess, her rig seemed very much at home.

And as for the "Best in Show" awardee, the 36ft Ainmara, only her hull and deck are as designed and built by John B Kearney in Ringsend in 1912. In Kearney's eleven years of ownership, she set a nuggety little gaff yawl rig with a keel-stepped mainmast only 37ft 6ins in overall length. But these days, she sports a sky-scraping Bermudan rig set on a deck-stepped alloy mast which the owner built himself, and painted brown to look like wood. As for her high-rise coachroof, that was installed in the late 1920s by Harland & Wolff in Belfast, whose speciality was ocean liners, and it shows.

Of the boats whose photos we displayed last weekend, only the little Albert Strange yawl Emerald, the Ramsey longliner Master Frank, the Pilot Cutter Madcap, the cruising cutter Dreva, the Manx nobby White Heather, and the 57ft 1957-vintage offshore racer Drumbeat looked anything like they did originally. The Galway Hooker Naomh Cronan was also of course authentic in appearance, but she was a new build of 15 years ago to the ancient design.

As for the others present in a large and eclectic fleet, many were old boats modified, sometimes very extensively, to provide individualistic vessels suited to the owners' tastes and particular requirements. Being an almost pathological boat modifier myself, I have to confess that my sympathies were largely with these boat changers. Whatever the outcome of their efforts, they were always interesting, and in most cases resulted in a much-improved boat, the success of the modifications being attested to by the very fact that they were at Peel and looking so well they picked up prizes.

But that said, our visit at the beginning of the "weekend" across to the 224-year-old Peggy at Castletown had brought something of an epiphany. She is an object of veneration. There was something extraordinarily moving about seeing and touching the boat which George Quayle had taken across the Irish Sea in 1796 to race successfully against the Windermere yachts. For sure, Quayle changed the Peggy about all the time in her very early years. But the boat we see and sense today is pretty much the boat of 1796, and her conservation planned for 2014 will be watched with special interest.

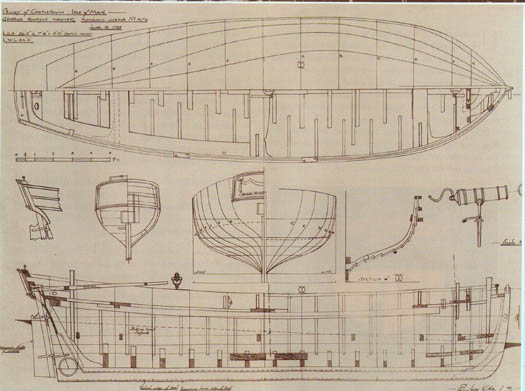

Hull details of the 1789-built Peggy of Castletown. Though the modifications added within three or four years of her building are evident, this is largely the boat which was taken to Windermere in 1796. While the original boat is being conserved during 2014, it is high time somebody in the Isle of Man thought of building a replica to go sailing.

She's of such historical significance that she's definitely not for sailing again. But as she has had her lines taken off and her construction details annotated, it strikes me that it's high time somebody in the Isle of Man built a replica to take out sailing. It would certainly add something very special to the Peel Weekend, a matter of entertainment and interest rather than obscure arguments about authenticity. But as the classic boat movement continues to gather pace, the arguments about what is or is not a genuine classic grow with it, and the heat of the argument has nothing to do with the size of the boats involved.

Thus at the delightful little port of Bosham in Chichester Harbour down in West Sussex, passions have been aroused at what is now the premier vintage and classic dinghy regatta, the Bosham Revival. The Portsmouth Yardstick handicap system is allegedly being exploited by some boats in the 14ft Merlin Rocket class, a vintage developmental design where boats which are effectively new build are being passed off as originals to the historic Jack Holt Passing Cloud design. This is being done on the basis of including an ancient thwart or knee from an otherwise totally decayed original.

Such an approach has been an embarrassing part of the classic yacht restoration movement from the start. By contrast, we are all aware of the painstaking care Hal Sisk and his team went to in restoring the 1894 Watson cutter Peggy Bawn, treading carefully on the lines between restoration, re-build and new build. As for conservation, if you claim you've conserved an historic boat, then it's a museum piece, and won't sail again.

Absolutely oozing authenticity.......the restoration of the 1894 Watson cutter Peggy Bawn by Hal Sisk and his team provides a global benchmark. She is seen here at Glandore Classic Regatta.

But of course, in revitalising significant and almost derelict old boats, the desire to sail them again is probably the prime motivation. And as for what qualifies as a classic and authentic under some old measurement rule, we're likely to see yet another wave of debate with the news that the great Chris Bouzaid and a team in the Royal New Zealand YS plan to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of the One Ton Cup's best era in New Zealand in 2015.

As mentioned here in a recent blog, the One Ton Cup was originally presented in 1898 by the Earl of Granard (later the Commodore of the National YC in Dun Laoghaire in the 1930s) for international racing in France between boats rating One Ton under a French measurement rule. It later lay dormant for a long time, but then in 1965 it was revived for RORC level rating competition for boats around 36ft LOA in an instantly successful series at Le Havre.

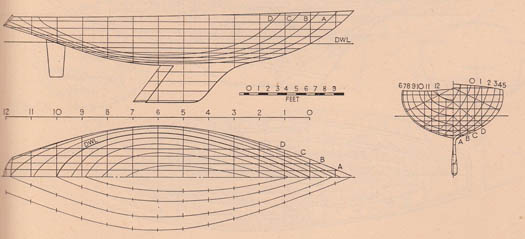

That was won by the Sparkman & Stephens-designed Diana from Denmark, a classic S & S offshore racer of the time, with rudder attached to the trailing edge of the keel. But 1965 was also the year in which a young American, Dick Carter, won the Fastnet with his own-designed 33ft Rabbit, steel built with separate spade rudder. So for the 1966 One Ton Worlds in Denmark, Carter turned up with the new steel 37ft Tina, beautifully built by the Maas Brothers in Breskens for Ted Stettinius, and they won the One Ton Cup from an exceptionally competitive international fleet.

The quality of the steelwork in Tina's hull is evident as she heads for victory in the 1966 One Ton Worlds.

The hull lines of Tina reflected Dick Carter's enthusiasm for the sections of the boats built to classic Scandinavian Square Metre Rules such as the 30 Square Metre. Steel was used to build the hull as Carter reckoned it conferred a rating advantage under the RORC rule, but it also enabled the skilled Maas Brothers builders to create an extraordinarily slim keel which was still sweetly faired at the garboards.

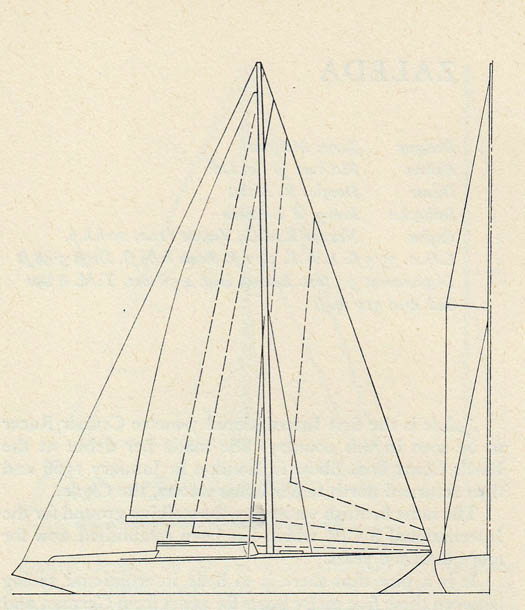

Dick Carter was the first to discern just how much rating advantage could be obtained by a large foretriangle under the RORC Rule in the mid-1960s, and as a result Tina's sailplan looks very odd today.

Chris Bouzaid's S & S design Rainbow from New Zealand won the One Ton Worlds in 1969 - and she also won the Sydney-Hobart Race.

The moment of truth in the final race – an offshore event – in the 1969 One Ton Worlds. Although Carter-designed boats were supposed to be better off the wind, while S & S designs excelled to windward, in the final miles running to the finish of the concluding offshore race Rainbow (right) wore down the defending German champion, the Carter-designed Tina-derived Optimist, and snatched the lead to take the One Ton Cup back to Auckland.

Carter designs won again in 1967 and 1968, but in 1969 with the racing from Heligoland in the midst of the North Sea, it was the very dedicated crew of the Bouzaid team from New Zealand with the Sparkman & Stephens-designed Rainbow who took the trophy. After that, the One Ton Cup had a dozen glorious years, typical being 1974 when the whole world focussed on the racing between Hugh Coveney's Ron Holland-designed Golden Apple from Cork and Jeremy Rogers' Doug Peterson-designed Gumboots from England, with Gumboots taking the win by a hairsbreadth.

This would be another gold standard participant in the One Ton Golden Jubilee Regatta in New Zealand in 2015. The 1974 Ron Holland-designed Golden Apple, owned by Hugh Coveney and built in Cork by Killian Bushe with Harold Cudmore as skipper, almost won the One Ton Cup, and was one of world sailing's superstars in the mid-70s. Photo: Courtesy RCYC

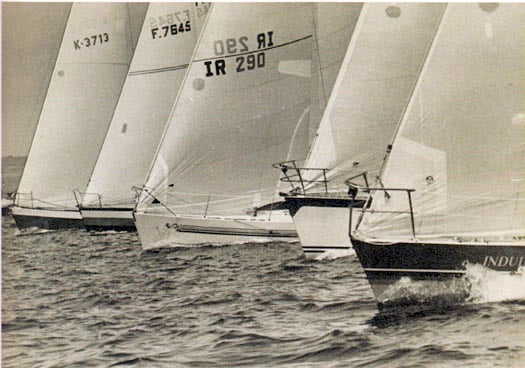

When Ireland finally won.....close-packed start at the One Ton Worlds at Cork in 1981, when the NYC's Frank Woods entered the Castro-designed Justine III (IR 290) with Harold Cudmore as skipper. In this challenging set-up, the positioning of Justine is a joy to behold. Photo courtesy RCYC

Golden Apple's main sailor had been Harold Cudmore, and after he'd won the Half Ton Cup in 1976, the One Ton Cup finally became his when he skippered the NYC's Frank Woods' Castro-designed Justine III to victory in the 1981 series at Cork. But in 1984 with the RORC Rule being replaced by the IOR, One Ton cuppers around 36ft became history, so the suggestion from New Zealand is that the Golden Jubilee Regatta should be restricted to the absolute classics created by the RORC Rule between 1965 and 1983.

Heaven knows there are enough of them about, but for most folk thirty years ago is a very long time, so fifty must seem like eternity. This is something which struck me a few years back up in Killbegs in Donegal when I was trying to get an arty photo, framed by the bows of super-trawlers, of a white boat lying to a mooring in sunshine. She looked like a Dick Carter boat, and when a little puff of wind swung her stern to, the name on the transom showed this wasn't just any old Dick Carter boat. This was Tina.

Quite what she was doing in Donegal I don't know, though I believe her owner lived in that mountainous county. But I haven't seen her there during the past few years, even though the local yacht fleet is increasing, with Killybegs due to get a 65-boat marina, while Killybegs Sailing Club is an important part of the northwest triumvirate of Killybegs SC, Mullaghmore SC, and Sligo YC.

So it's now a long way indeed from the old days when that late great Killybegs fishing skipper James MacLeod was so keen on the sea that in his time off fishing he nipped down to Rosses Point to race his GP 14 with the Sligo fleet. Now there was a man, and no mistake.

This morning, however, the current whereabouts of Tina have added interest with the news of the One Ton Golden Jubilee in New Zealand in 2015. Having seen the interest which the Half Ton Classics have engendered, we can guess at some of the boats which will emerge in order to be eligible for the One Ton Classics in 2015. But in such a line-up, the steel-built Tina of 1966 would be Gold Standard.

With classics restoration, you need a balance between love of old boats, and a can-do ability. Obviously you also need lots of money, but that could be disastrous in itself, as the spirit of the boat has to be preserved. Many rich people automatically think new is best, and in purely functional terms it is certainly much better value, but with classic boats and yachts, you're into strange territory.

A case in point is to be found on the shores of Chichester Harbour, where the mortal remains of the 12 Metre Flica are to be found in a shed beside the marina at Birdham Pool, which is itself a place of historical fascination, as it was the first yacht harbour to be created in a pool which backed up an old tide mill.

Flica was the big boat around Cork Harbour in the 1950s. Owned by a man of style, Aylmer Hall, she exuded all the style of a classic which had been designed by the great Charles E Nicholson in 1928, working in conjunction with the tank and wind-tunnel research team of the owner, aviation magnate Richard Fairey.

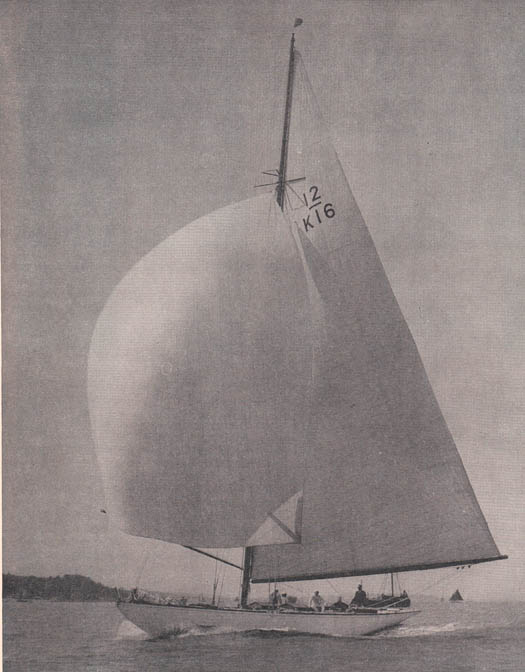

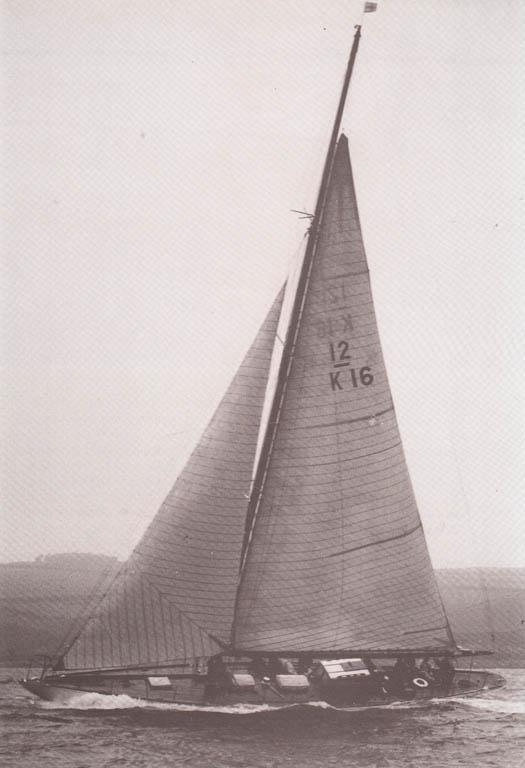

During the period 1928-1938. Flica was the most successful 12 Metre of all in the Solent. She is seen here off Cowes under the ownership of Hugh Goodson in 1936.

In terms of longevity at the sharp end of the 12 Metre fleet, Flica was only to be rivalled by the Sparkman & Stephens designed Vim which appeared in 1939, but as World War II interrupted international racing for the Twelves, it was Flica which had the longest run of success, and she was reckoned as the boat to beat for much of the 1930s when she was owned by Hugh Goodson.

The 12 Metres of that era – boats around 66ft in overall length – were wellnigh perfect, being elegant of appearance, manageable in size, and yet large enough to be impressive. Thus it was a stroke of genius by Aylmer Hall to acquire Flica in 1950 when life in Ireland was becoming decidedly dull and small-minded, for Flica was none of these things. To add greatly to gaiety of the nation and life's rich tableau, she even managed to be spectacularly dismasted during the Cobh People's regatta of 1957, fortunately without anyone being seriously injured, but they talked of little else around Cork Harbour for years.

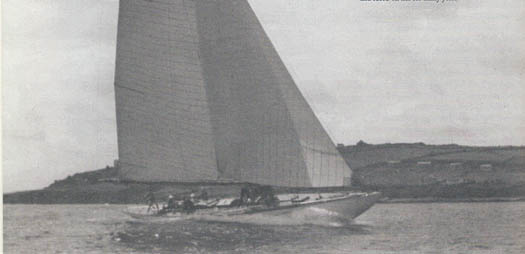

When Aylmer Hall brought Flica to Cork Harbour in 1950, he introduced much-needed style when there was little enough of it about in Ireland. Photo courtesy RCYC

Flica storming seaward from Cork Harbour on a less-than-summery day. At such times, people wondered what it would be like if her mast broke. At Cobh People's Regatta in 1957, they got their answer, but fortunately nobody was seriously injured.

Quite how this supreme classic is now mouldering in the shed at Birdham I don't know, and perhaps I'd rather not know, as it must be a great sadness for someone. I first happened upon her in 2012, and already it looked as though restoration had long since ground to a halt. In late September this year, there was little or no change, only more dust, so much so that the locals must see her now as part of the scenery, an inexplicable bit of background which is simply accepted.

Flica as she was in late September 2013, awaiting a restoration which seems to have ground to a halt. Photo: W M Nixon

Flica is now a long way from the Solent champion of the 1930s, and the Queen of Cork Harbour in the 1950s. Photo: W M Nixon

Her counter stern seems more beautiful than ever – this was Charles E Nicholson on top of his form Photo: W M Nixon

The empty interior, looking aft. The accumulation of dust suggests this restoration has long since ground to a halt. Photo: W M Nixon

Seeing a significant boat merely as unremarkable background is something which can happen to all of us. Back in 1996, we cruised to St Malo in order to see the first yacht built by James Kelly of Portrush. Built in 1897 for Belfast-based cruising pioneer Howard Sinclair, who designed the boat himself, the 40ft Nuada had originally been called Saiph. But Sinclair acquired a taste for having new boats built, so after a year he designed and had James Kelly build a 15-tonner called Yucca (his boat names were just horrible), and Saiph became Nuada in Scottish ownership, and in time a distinguished part of the Clyde Cruising Club fleet for many years.

Somehow or other she found her way to France, and we'd got to hear about her in the ownership of Bernard Julienne of St Malo, so this provided a good excuse to cruise to that wonderful port. We even took along a bottle of Bushmills whiskey to present to Bernard, as it's distilled just six miles from where Nuada had been built, in a little boatyard where James Kelly subsequently built many yachts, including three boats of the Dublin Bay 21 Class, and seven Howth/Dublin Bay 17s.

And no, it's not a Convocation of Silly Sailing Hats. In St Malo in 1996 beside the bow of the 40ft Nuada, which was built in Portrush in 1897, Ed Wheeler of the Irish Cruising Club presents a bottle of Bushmills whiskey (distilled just six miles from Nuada's birthplace) to Bernard Julienne, owner of the boat. Photo: W M Nixon

Nuada was in mid-restoration, or rather what people hope is mid-restoration with all the interior stripped out and everything cleared for action. In reality, you're about a tenth of the way there. So naturally much of our interest was in this massive work project, the prospect of which was overpowering. We clowned about a bit with the Bushmills presentation and took our leave, for as it was lunchtime, and this was France, there was nobody around to ask about the boat next door, which was also in a sorry state. She was much bigger than Nuada, and looked really interesting. She was called Pinta.

It was only in the post formal clowning around that we got a photo which showed anything of the boat next to Nuada. And it was only later that we discovered she was originally Vanity V from 1936, the last 12 Metre designed and built by Fife of Fairlie. Photo: W M Nixon

It was only in the post formal clowning around that we got a photo which showed anything of the boat next to Nuada. And it was only later that we discovered she was originally Vanity V from 1936, the last 12 Metre designed and built by Fife of Fairlie. Photo: W M Nixon

Some time later we discovered Pinta was originally Vanity V of 1936, the last 12 Metre to be designed and built by Fifes of Fairlie. Like it or not, there's a pecking order in classics. We may have originally gone to St Malo to see the first yacht built by James Kelly. But the fact that we'd been right beside the last and greatest 12 Metre from the Fife stable has become the dominant memory of our time there. Cruel as it was, the restoration or otherwise of Nuada became something very far down the line from a new interest in whether or not Vanity V ever got restored.

Happily, she did. Vanity V has since become an adornment of the Baltic classic yacht scene. Wouldn't you just love to do something similar for Flica?

What Has Happened to Sailors' Traditional Self–Reliance At Sea?

#safetyonthewater –Can it really be true that lifeboat call-outs in Ireland in 2013 – most of them for recreational boating of some sort - showed a staggering increase of 43% over 2012? W M Nixon discusses the disturbing figures, and considers whether it is possible to re-build the traditional amateur seafaring tradition of competence and self-reliance.

Time was when the most respected sailing folk, the people with the highest standards in their boats and in their use of them for their dedicated style of seafaring, were accustomed to sail the sea on the principle that they would much rather drown than cause any inconvenience or danger to other seafarers in any way whatsoever.

This applied particularly in the matter of being rescued. Being rescued just wasn't done. It was a sign of appallingly poor seamanship. Indeed, having what other people might describe as an adventure of any kind was frowned upon. "An adventure" was looked upon by the pioneers of cruising - just as it was looked upon by their contemporaries, the top explorers - as evidence of incompetence.

It was an admirable if impossibly idealistic attitude, which had its roots in the earliest days of amateur seafaring. In that distant era, the first very few pioneers were venturing forth for pleasure on seas where working people with much less in the way of economic resources were struggling to make a usually poor and often dangerous living as fishermen. To emphasise the difference, pleasure sailors only fluttered about the place in summer like butterflies, whereas those who worked the sea in small boats had to face its ferocity all year round.

Also sharing the sea were the crews of cargo carrying vessels whose demanding owners did not welcome tales of their vessels being delayed and the valuable cargoes put at risk, even for the shortest possible periods, in order to assist or rescue some incompetent amateur. As for the regulators of the sea, the naval ships and the revenue cutters, they were naturally suspicious of people going about their inexplicable business with "pleasure" as their reported objective, sailing hither and yon in their strange little vessels.

They undoubtedly were "little" vessels, as the new sport of cruising with its codes of a high standard was developed by the emerging middle classes of the 19th Century. Unlike the aristocracy and monarchy, who would sail the sea in large yachts with crowds of attendants and everything – including rescue if needs be - done in a very public manner as part of the grand life's rich tableau, the middle classes valued privacy above everything else.

Thus the code of self-reliance in cruising evolved, propounded by folk like Richard Turrell McMullen, who developed the principle of total self-reliance to such an extent that even in coastal waters he cruised single-handed in his final years. And even when pleasure boats numbers and rescue services had developed to an impressive level in the late 20th Century, the "shame of being rescued" was still a very potent attitude which encouraged high standards in boat maintenance and seamanship.

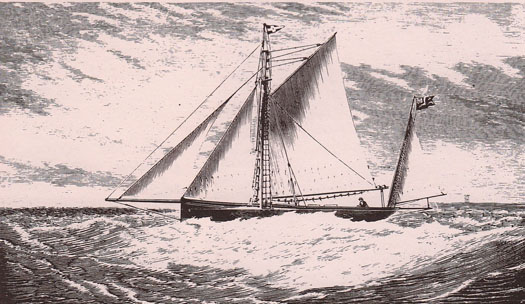

Pioneering seafarer Richard Turrell McMullen in his 42ft Orion, with which he cruised the Irish coast in 1869. McMullen expounded a doctrine of self-reliance and competence in amateur sailors, and would have regarded being assisted by the lifeboats as a matter of extreme shame.

But today, well into the second decade of the 21st Century, the RNLI call-out figures for Ireland do not make happy reading for advocates of rugged seafaring self-reliance. Could it be that the ubiquitous presence of highly-visible lifeboats in our main harbours, with their presence further publicised at major rescues, is creating excessive haste in calling them out for non-emergency reasons?

Admittedly the summer of 2013 was so good that there were many more people afloat in June, July and August than in 2012's grim conditions. Thus many of those rescued will have been casual impulse boaters, rather than dedicated seafarers. But nevertheless a year-on-year increase of 43% in lifeboat launchings, most of them for recreational boating of some sort, is very discouraging for an activity which supposedly prides itself on its capacity for sensible self-regulation, and derives satisfaction from overcoming challenging conditions without assistance.

The Dun Laoghaire lifeboat on exercise in Dalkey Sound. This was Ireland's busiest station in the summer of 2013, with 34 call-outs in June, July and August Photo: David Branigan/Dun Laoghaire RNLI

For the record, Dun Laoghaire was the busiest station with 34 call outs. Portrush in County Antrim was next on 26, just ahead of Crosshaven with 25, while Fenit, Wicklow and Skerries (where their new boat, the Atlantic 85 Louis Stimson, was named and dedicated on Saturday September 7th) were all on 17.

The new lifeboat at Skerries, an Atlantic 85, was dedicated and named the Louis Simson on September 7th. The Skerries station had 17 call-outs during the three summer months.

Of course there are those who will claim that, in many instances, talking of "rescues" would be over-stating the case. When a situation looks like being serious from the outset, the Coastguards – and particularly their helicopter – will get involved. In fact, so many genuinely life-saving events involve helicopters that it's surprising no-one seems to have thought of a rescue helicopter service service funded by charities. Maybe they have, but have found it would be impossibly expensive. In any case, with lifeboats, there's the obvious and stirring maritime link. "Those in peril on the sea" must be one of the most recognisable phrases known to us, and providing charity support to lifeboats is a direct and very satisfying way of connecting with it.

But the fact that the lifeboats receive so much of their funding from charity, and are manned largely by volunteers, adds to the moral overtones when any rescue is successfully carried through. And as we cannot know how even the most minor boat difficulty might go pear-shaped at some future stage, then if the lifeboat gets involved, the perception is that you've been rescued however minor the problem may have been, and notwithstanding the fact that the lifeboatmen themselves may phrase their report to spare the rescued crew's blushes.

The lifeboatmen's attitude is better safe than sorry, and much better safe even if just slightly embarrassed. But an analysis of the incidents in Irish waters is intriguing, and they provided some events with unwelcome publicity. For instance, the ISA's Gathering Cruise-in-Company from Dun Laoghaire towards Dingle in July experienced four different lifeboat call-outs.

The highest-profile incident was the rescue of the crew of 30 from the tall ship Astrid when her engine failed on the short hop from Oysterhaven to Kinsale in fairly rough conditions of onshore winds. One possible story suggests that prior to her arrival in Ireland, one of Astrid's fuel tanks had been accidentally filled with fresh water, which is something that can easily happen in a large and complex old sailing ship during a busy turnaround time in port. In line with their spirit of self-reliance, Astrid's crew had reportedly declined offers of professional assistance in making the tanks diesel-ready again. But despite their best efforts, it seems there might have still been a small quantity of fresh water left, quite enough to cause what became a catastrophic engine stoppage.

The end of a dream. The sinking of the privately-owned Dutch sail-training tall ship Astrid was a catastrophe, but it wasn't a tragedy as all 30 on board were efficiently rescued by the lifeboats. Photo: Bob Bateman

In fairness to The Gathering Cruise-in-Company, the Astrid sinking was a big ship event with which they became associated almost incidentally. But the three other call-outs were directly linked. The second most serious (after the Astrid) of the Cruise-in-Company's call outs was for the Ballycotton Lifeboat for an injured crewman on a 42ft yacht six miles southwest of the port. Injuries were such that the casualty was transferred by lifeboat to a waiting ambulance at Ballycotton, then as the injured person was a key member of the 42ft yacht's crew of three, the lifeboat returned to the cruiser and escorted her to port.

The other two lifeboat callouts for the Cruise-in-Company were to assist a yacht with her propellor fouled by a fishing pot marker off Kilmore Quay, and to tow in one of the participating boats after her engine had failed off Kinsale.

The hazard of getting fouled in fishing pot lines is even greater in Ireland than other similar places like Cornwall, where Ben Ainslie has written of his family's experience of having their fine yacht driven ashore at the entrance of the Helford River and getting badly holed on rocks, after the propellor had knotted itself in a lobster pot line. The lobsters and crabs along the Irish coast being even more prolific, it's a constant problem when under power, and there are few challenges more daunting than motoring in late afternoon straight into the sun on passage from Carnsore Point to Kilmore Quay, and knowing that the entire route is a maze of pot markers, some quite clearly defined, others lurking just below the surface in the strong tides, and all virtually invisible with the notorious brightness of the sunny southeast right in your eyes.

So for cruising in Ireland, an obvious solution is one of those cunning little cutting devices fitted to the propshaft to slice through any ropes, but even they can be defeated by too much rope. When it does happen, a serrated bread knife with the means of and quick and easy attachment it to the boathook can sometimes work wonders.

But the proliferation of cruisers with SailDrives exacerbates the problem. They may fulfil the designer's dream of having the propellor immersed as deeply as possible, and in clear water too, but it means they're perfect targets for wayward pot lines, and you need a diver or a liftout to get at them if they become fouled.

But do propellers really need to be so deeply immersed? After all, in motorboats they're close under the surface, and often reasonably accessible by long-arm methods from a dinghy. Admittedly with a sailing boat with her extra pitching through having a mast, there is a danger that a shallow-mounted propellor will come out of the water as she punches into a head sea. But for years I'd a share in the Contessa 35 with a high-mounted propellor well aft, and it never came out of the water while motoring in a head sea. Yet thanks to the boat's pintail stern - which had few other merits - you could just about reach the prop from the dinghy, whereas today's wide-sterned boats might preclude that. Whatever, in re-aligning the engine in my current boat, something which just had to be done when I discovered the builders had installed it at an angle of 21 degrees plus, when the manufacturers insist it should be no more than 15 degrees with 7 degrees is an ideal target, I now have a setup where the propellor can be reached by clambering down the stern boarding ladder.

All of which is little enough comfort for a cruising boat with a fouled propellor being rescued by the Kilmore Quay lifeboat during the Cruise-in-Company, but that in turn begs the question: Where were the other cruisers-in-company when this situation arose? The notion behind a cruise-in-company is that there's a feeling of mutual support, and minor problems can be dealt with by assistance from your fellow participants. But even in the companionability of a cruise-in-company, could it be that we've become so accustomed to hearing about the use of rescue services that even with buddy boats presumably near, an everyday get-you-home problem can still lead to an emergency call?

It seems to have happened with the lifeboat going to that engineless boat's aid off Kinsale and more recently the maritime community expressed shared embarrassment when the crew of a cruiser-racer of a notably able type called out the lifeboat when their engine failed as they sat becalmed off Wicklow Head.

But as boat numbers increase, professional privately-run services develop to meet the growing need for assistance like this. In boat-crowded places like Long Island Sound, and indeed on many parts of the coast of the USA, commercial assistance and get-you-home services have been a feature afloat for many decades. And anyone who has been around the Solent will be familiar with the SeaStart service, to which you can subscribe as a sort of insurance, and which now does commercially many of the tasks which used to take up too much of lifeboat time.

{youtube}VrqzFIfV1w4{/youtube}

Even the colours of their boats suggest that SeaStart is the same reassuring presence afloat as the AA is ashore.

Interestingly, SeaStart now sees its role as including the education of its less-experienced subscribers in order to raise their standards of boat and equipment maintenance, and improve their attitudes to sailing the sea. Yet because it's all being done by what is essentially a commercial organisation, those availing of its services don't feel themselves being morally oppressed by a do-gooder organisation or an interfering nanny state.

It works well in a densely-boat-populated area like the Solent region, but we have to face the reality that Ireland has an enormous and often rough coastline, and boat numbers are relatively very few, and often far between. So for now and the foreseeable future, most of us in day sailing, cruising and offshore racing are going to have to rely on self-regulation with a sensible attitude to seafaring, and the use of voluntary services supported by charitable donations in emergencies.

The situation is of course very different in inshore racing, where highly organised club rescue teams with their crash boats, and an admirable ethos of efficiency among their crews, set a standard of self-help and self-regulation which is a credit to our sport. But as soon as the scope of the event spreads from the purely local, and the boat-size goes beyond dinghies, we find ourselves interacting with national emergency and rescue services.

So in seeing the MOD 70 trimaran capsizing in Dublin Bay in June and observing the flurry of helicopter and lifeboat activity – all very necessary as two crew were soon in hospital, one for an extended stay with a severely fractured pelvis – we were seeing a new world. It's a situation very far removed indeed from the schooner America making her unaccompanied way across the Atlantic in 1851, with no contact with anyone until, without fuss or bother, she prepared for the historic race around the Isle of Wight which in its turn was sailed without any expectation of the use of rescue services.

And for those of us in the less exalted areas of personal choice sailing, it really is a matter of self-regulation if we are going to avoid having the authorities impose regulation upon us. In considering this disturbing 43% increase in lifeboat call-outs in 2013, it's difficult to avoid the conclusion that the only reason there aren't threatening rumbles of regulation and inspection from the government is simply because of the dire circumstances of the national finances.

Were we not in a situation of government cutbacks on every front, it's highly likely there'd already be some advisory body looking at ways of making the boating world adopt a more responsible, self-reliant and disciplined attitude towards its activities. That in turn would lead to an increased inspectorate and more supervision, with further erosion of the sense of freedom in sailing the sea. And in the end, it's boat people who would have to pay for it themselves. It's up to us to protect this activity we cherish so much, and to treat it with the respect it deserves.

Maguire the Man for Third Hobart Win

#sydneyhobart – If you want guaranteed publicity for an international sailing race, start it at Christmas and send the fleet on an attractive course which is easily comprehended by the casual observer. Throw in the possibility of rugged weather and a real hint of danger, and hey presto, the sailing world wakens up from its post-Christmas slumbers and starts to pay attention.

But if you're thinking of taking this sound advice and inaugurating a new race, forget it. The annual Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race got there long ago. And when it starts in its usual spectacular style on St Stephens Day out of Sydney Harbour at its mid-summer best, be sure that sailing enthusiasts all over the world will be logging on to follow top-level sea sport.

Irish interest is extra-high this year, as the defending champion is one of our own, Gordon Maguire. He may be well settled in Australia, but he and his family return to Ireland most years. Maguire's move Down Under began in 1991 when he was one of the Irish team which won the Southern Cross Series culminating in the 628-mile Hobart Race which he won, helming for Harold Cudmore.

Twenty years were to elapse before Maguire was reunited with the Tattersall Cup, the trophy for the Sydney-Hobart overall win, which he shared as sailing master aboard the victorious four year old Reichel Pugh 63 Loki, owned by Stephen Ainsworth with further high quality experience provided by navigator Michael Bellingham.

With Maguire in charge on deck, they have someone who brings a hyper-intelligent analysis and a prodigious natural sailing talent to the challenge of sailing a thoroughbred offshore. For instance, most offshore sailors today think it's all done by instruments. Not so Maguire. He becomes almost mystical when discussing what it's like to helm a big boat as she settled into the fastest groove, and how to keep her there.

"The heel of the hull feels just right, the helm is firm – not too light, not too heavy, and the sails set at just the right angle, in the sweetest shape" he comments. "There is no substitute for feel. The information from the instruments is all historical. It takes four to five seconds for the instruments to do the calculations from when the cause of the drop in speed occurred. People who drive on the instruments are always four or five seconds behind. They are reactive, and the boat is slow. The brain is so much faster at processing all the information coming in at once than the onboard computers".

Maguire reckons that too much focusing on dials engages the front of the brain, whereas top helms instinctively rely on the subconscious, and this is particularly important in the offshore marathons. "If you consciously concentrated for that long, you'd go mad in half an hour. I switch my mind off. I am not really concentrating. Sometimes I don't know what has happened in the last 30 minutes of sailing".

It's not something you should try at home, but when Maguire is in the groove, he's unbeatable if his tactician and navigator have sent him the right way. They did that to perfection in the 2011 Sydney-Hobart Race, and Loki won overall by a cool 50 minutes. With 80 top contenders lined up for this year's event, there's no doubt about which is the boat to beat.

GOOD NEWS FROM GREYSTONES

Optimistic politicians are always looking for the first green shoots of recovery in these grim economic times, and they might find them this weekend in Greystones, where the new harbour was finished in basic form, but further development had come to a halt. There, the good news is that BJ Marinas, harbour contractors Sispar, and Wicklow County Council have signed on the dotted line for Bernard Gallagher's company to take on the running of the new marina.

BJ Marine are best known as international yacht brokers and agents of more than 35 years experience with offices at Malahide Marina, in Bangor, and in Malta. But they also run the boatyard at Bangor Marina, and have their own marina in Malta.

So they're up to speed with the practicalities of installing waterfront infrastructure. Green shoots notwithstanding, they won't be allowing the grass to grow under their feet down Greystones way. The marina furniture is already being built, it will be 100% Irish, and the first hundred berths will be available in Greystones by April.

We can expect cruising groups and passage racing organizers on the East Coast to be re-jigging their 2013 programmes accordingly. In addition to those living in the north Wicklow area who have long been seeking a permanent secure berth which doesn't involve having to battle the traffic to get to their boats in Dun Laoghaire or Poolbeg, Greystones is a very manageable destination by sea from other ports in the Greater Dublin area. It's within the DART network, which helps greatly with crew logistics in these busy times when some might wish to stay with the boat overnight, while others have other demands on their time.

With a marina, Greystones will find itself becoming an option for staging keelboat events, while the new facility will make the managing of dinghy events much easier – dinghies may only need a slip, but committee boats require a pontoon berth. So the news from Greystones is good, and it should be a wake-up call for something similar in Skerries. Meanwhile, congratulations to Bernard Gallagher and his team.

FROM PORTRUSH TO BALLYDEHOB

It's a long way from exquisite teak-laid decks that the ancient Howth 17s were reared. But when a class has been going for 114 years, a little teak treat and some intensive TLC is well earned. Not that the original timber used was suspect. Although basic stuff, it was of good quality. But in those days in the 1890s it was expected that one design classes would be replaced by newer designs at regular intervals, and some boat types reputedly had it written into their rules that their one design class association would be automatically wound up at the end of seven years.

So the notion of the boats lasting well beyond the century wasn't on the agenda at all. But thanks to a mixture of an attractive design and the boat's main association being with a very particular port in a very peculiar place (let's face it, Howth is odd), the Seventeens have been kept going well beyond their natural life span. And every so often, one of them gets smothered with an almost unhealthy amount of cosseting.

The latest one to be reborn is Deilginis, Number 11, delivered back to Howth on Thursday from master shipwright Rui Ferreira's workshop in Ballydehob in West Cork, sporting an exquisite new teak laid deck, and with much hidden but necessary work done down around the garboards and the keelbolts.

Deilginis is one of the seven boats to the design built for members of Dublin Bay Sailing Club in 1907 by James Kelly of Portrush. In those days of joined-up railway systems, they were delivered efficiently all the way by rail from the harbourside station in Portrush to the harbourside station in what was then Kingstown.

Although the class had originated with the first five boats in Howth racing from May 1898 onwards, in letting DBSC use their design the sailors from the little Howth SC were letting a cuckoo into their nest. The class was known on the Southside as the Dublin Bay 17, and for a while its Northside (or more accurately Eastside) origins were airbrushed almost completely out of world sailing knowledge. But the Eastsiders bided their time (after all, Howth is geologically twice as old as nearby Ireland), and as the fickle Dublin Bay types began to turn to fancy Bermudan rigged boats in the 1960s, the Howth men reclaimed their own.

One who played a leading role in this was Nick Massey. Around 1970 he realised that no-one could account for Deilginis, despite the fact she'd originally been built for the family of the Commodore of DBSC. Nick found her in a sorry state in a yard in Dolphin's Barn – the former Commodorial yacht had become a sort of little fishing cruiser, and was no stranger to the copious use of tar. His wife Liz, as keen on the Seventeens as her husband, quickly bought the boat, and they got her back to Howth and into commission for the class's 75th Anniversary in 1972, when all the boats had become Howth based.

Over the years, Deilginis went through a number of ownership permutations, but in 1993 Nick found himself involved again with a syndicate, and that's the way the boat has been kept going since, with a rolling syndicate involving changing membership drawn from several families. As the 2012 season went on with continued hard sailing, the syndicate agreed that the old boat needed several jobs done with varying degrees of urgency, so they looked around for a craftsman who could undertake the job, and give some promise of it being finished within a reasonable time scale.

Schull's sailing supremo Davy Harte was visiting in Howth, and Nick sought his advice. Harty suggested Rui Ferreira, who is gaining a formidable reputation down Ballydehob way for quality work on classic boats. Rui was up within days to assess the job, by September the Howth 17 was in the Ferreira workshop (it took a bit of shoe-horning to get her in), and after an intensive period of immaculate and very focused work, three months later Deilginis was back in Howth nicely on time for Christmas, the essential hidden work skillfully done, and the new deck looking only gorgeous.

The new teak deck is fitted to the 105-year-old Deilginis in Rui Ferreira's workshop in Balkydehob. Photo: Anke Ferreira

Looking only gorgeous – Deilginis with her new deck back in Howth on Thursday December 13th. Photo: W M Nixon

Happy customer – Nick Massey (left) of the Deilginis syndicate with Rui Ferreira. Nick has been actively involved with the Howth 17s for more than forty years. Photo: W M Nixon

Some Kite Flying for an Olympic Decision

#isaf – Kites or sailboards to be highlighted the most exciting form of sailing in the 2016 Olympics? If you're waiting for a clearcut answer from the continuing deliberations of the International Sailing Federation currently under way at their Annual Conference in Dun Laoghaire, then don't hold your breath.

Of all the world's capital cities, it is Dublin which is probably most aware of the growing impact of windsurfing and kite-surfing as hugely accessible forms of sailing which can take place off any beach. The greater city area is so well-endowed with miles of sand which can provide world class sport when the wind is up that, like it or not, we ordinary Dublin beach-walkers have become connoisseurs of the kiting versus sailboards controversy.

So although it may have discomfited many traditionally-minded national sailing establishments when sail-boarding became an Olympic sport, we Dubs were ahead of the posse. We were already looking to the next move. For we knew that, when surrounded by kitesurfers at choice venues like Dollymount Strand, sailboarders can seem like dowagers at a disco.

Thus with world sailing's sometimes embarrassing desire to appear hip, it was no surprise back in May when it was announced that, albeit by the narrowest of voting margins, kite-surfing would replace windsurfing at Rio in 2016. But while it may have been a definite decision, seems it wasn't a binding one. As far as we can gather, the relevant section of the current conference (which has 700 delegates in all) have changed their mind on the kiteboard/sailboard Olympic thing. Well, sort of.

Admittedly, we'd been looking forward to using a headline which leaps from the page, and would have become part of international sailing history. "The Dublin Decision" would certainly have wings. But we're currently looking at "The Irish Indecision". Or more accurately, "The Continental Compromise". Thanks to notable eloquence from the Continent in the form of delegates from Spain and Eastern Europe, we've ended up with a compromise which, at the time of writing, will see both windsurfing and kite-surfing at Rio, but put together in some mixture which won't involved an increase in sailing's Olympic medal allocation, which is always under scrutiny.

For that of course is the nub of the matter – the place of sailing in the Olympics. It's not an arena activity, and it's definitely a vehicle sport – that's two negatives. It could be that in the future, only the most minimal sailing vehicles will be accepted as sufficiently athletic for Olympic inclusion. Maybe some time we'll look back fondly to the days when boats were used in the Olympics, as kitesurfing in all its forms becomes the only Olympic sailing category.

Meanwhile, the Dun Laoghaire deliberations have been good for Ireland in that outgoing ISAF President Goran Petersson was lavish in his praise for the superb style of Dun Laoghaire's organisaton of the International Youth Worlds in July. But there was a poignant moment for the Irish sailing community at the World Sailors of the Year Awards at the Mansion House on Tuesday night.

Multiple Olympic Gold Medallist Ben Ainslie of Britain took the men's award, so no surprise there. But history was made with the Women's Award going to Lijia Xu of China for her Gold Medal in the Olympic Laser Radials. At the beginning of the sailing Olympics, she was scarcely figuring in the results at all, while Ireland's Annalise Murphy was piling on a substantial overall lead. But the Chinese sailor just got better and better, and was ahead when it mattered – at the finish of the last race. It was a mind-blowing lesson in sports psychology.

PETE HOGAN'S LOVELY BOOK

Much time may have passed since he did it, but nothing will ever change the fact that sailor/artist Pete Hogan of Dublin was the first Irishman to round Cape Horn single-handed, sailing his gallant little Tahiti ketch Molly B. He wrote about it at the time, but now with the mellowing of the years, he has written and illustrated a lovely book, The Log of the Molly B, which is being launched next Wednesday (November 14th) in the Davenport Hotel in Dublin's Merrion Street at 6.0pm by Conor Brady, former editor of The Irish Times.

There's an open invitation to the launching for the entire sailing community, and any other well-wishers too, for that matter. Of course there is an expectation that you'll feel moved to buy the book. But that's no hardship – it's a real page turner, a joy to have and to hold and to read, beautifully produced by Liffey Press, and at €19.95 it's priced just right.

There is of course much more to it than the rounding of the Horn. The Log of the Molly B perfectly evokes the mood of the 1980s, and an approach to seafaring and ocean wandering which harked back to the era of the great individualists and legends of the sea, rather than being overpowered by the shiny new era of advanced marine electronics and high tech sails and rig, set in a framework dominated by official safety requirements.

So if you're in the mood to savour the atmosphere of a gaff rig gathering and celebrate the true spirit of voyaging, the Davenport next Wednesday at 6.0 pm is the place to be.

Creatures of the deep – a giant manta ray take flight past Pete Hogan's ketch Molly B, one of his many attractive illustrations for his new book "The Log of the Molly B".

THE JOY OF WORK (when others are doing it)

It was intriguing to note that one of the most popular features at the recent Hamburg Boat Show was a special active exhibition where damaged or worn glassfibre boats were given the complete restoration treatment during the course of the show.

It all sounds rather un-Germanic - you'd think their attitude would be that such things should be done by professionals behind closed doors. And heaven only knows what the front-line exhibitors showing shiny new boats made of the fact that so much attention was being given to scruffy old ones. But it was a runaway success, the DIY brigade loved it and learned much from it, and of course for the ordinary Joes and Josephines who wouldn't dream of doing their own maintenance and repair tasks, there was the eternal fascination of watching work in progress.

Those of us who were lucky enough to be allowed in to the workshop at Collins Barracks when John Kearon and his team were conserving Asgard could only reflect that it was a pity that when the historic old ketch was finally put on display, it would be as a static exhibit. In many ways it was more interesting when the work was in progress, not least when the team of voluntary riggers from Howth, led by Pat Murphy and Neville Maguire, were on the job to provide enough in the way of spars and rigging to give a better impression of what Asgard was like in her heyday.

However, the work has been so well done that even with the old girl now totally at rest and on display, it's a very complete exhibition, encompassing the development of yacht design and building with an insight into a very complex period in Irish history.

With a well-chosen selection of photos, the human interest shines through in unexpected ways. We already knew that Erskine Childers' friend and shipmate, Gordon Shephard, had an easygoing approach to life despite twice being the recipient of the Royal Crusing Club's Chakenge Cup, the world's senior voyaging award. He won it in 1911 and again in 1913, the latter year as skipper of Asgard on a late Autumn voyage from Norway to North Wales, going west of Scotland.

In the Great War, immediately after the gun-running of 1914, he became the youngest Brigadier, on active service with the Royal Flying Corps. He did not survive the war. Yet up in Collins Barracks, he is forever alive, aboard Asgard as she sails along in July 1914 laden to the deckbeams with vintage guns, photographed at the helm wearing what look like an old and not at all stylish cardigan, the very essence of the happy-go-lucky cruising man.

The conserved Asgard on display in the museum at Collins Barracks. The exhibition provides a valuable insight into the cruising yachts of her era, and the human story of those involved in a complex historical episode. Photo: W M Nixon

A True Story That Actually Happened

#sywoc – When something seems just too good to be true, it usually is. But just now and again, though only very occasionally, it is good and it is true.

On Wednesday evening, followers of the Irish team in the Student Yachting Worlds at La Rochelle in France were in a state of wonderment and hope. Could it really be that, after 13 races and a "Stewards' Enquiry", UCD were actually leading overall by all of 12 points?

And after all the disappointments at the final hurdle in so many international sailing events this year, could it possibly be the case that with just two more races to sail, admittedly in a decidedly hot fleet, could it be that Cathal Leigh-Doyle and Aidan McLaverty and their crew of ten could hang onto their lead right through to the prize-giving today – after all, it only needed them to be just one tiny little point clear?

In such a situation, first thing is a look at the weather prospects. Mostly the breezes in the region were fresh west to southwest, but the forecast charts showed a bullet of stronger wind barreling its way up the Bay of Biscay, right on line for La Rochelle through Thursday and yesterday.

Initially it didn't look too rough, but then we got to thinking that they'd go out to race in tough conditions, and UCD might get dismasted. That's the way you get to think after a season of disappointments like 2012. But the ill wind blew Ireland good. It arrived as a gale, and further racing was eventually cancelled. We were home and dry.

It had been an excellent series already, and the Irish team had excelled both inshore and offshore. For part of this week, they were racing in the knowledge that points gained in the second race had been lost through an alleged start line infringement. But eventually an official analysis of video evidence showed Ireland to be all clear, and with the points reinstated they moved into this massive overall lead.

"Massive overall lead", however, has been the bugbear of Irish international sailing this year. Get one early in any major series, and the opposition will naturally gang up on you. But thanks to the weather, this time they didn't have the opportunity, and in truth it's difficult to see what they could have done anyway, short of outright sabotage.

Our team were Cathal Leigh-Doyle, Aidan McLaverty, Barry McCartin, Ben Fusco, Simon Doran, Theo Murphy, David Fitzgerald, Ellen Cahill, Isabella Morehead and Alyson Rumball. They come from every corner of Ireland, they represent virtually all the main sailing centres and many smaller ones throughout the country, and they've all done us proud.

Amidst this deserved euphoria, there's no better time to put the record straight on Ireland's scorecard in student world championships, about which we've all been a bit confused, not least this column.

The Student Yachting World Cup is now top of the bill, but although it was founded back in 1979, another competition in France tried to claim its crown. That was the Course de L'Europe at Le Lavandou in the south of France, which had a greater emphasis on offshore racing. In 1988, Trinity College Dublin took part representing Ireland, and they placed third overall out of twenty national teams, an impressive fleet which the current competition has not recently matched. The Irish team nearly a quarter of a century ago was Gary MacCarthy, Paddy Oliver, Sean Hooper, Sarah Webb, Helen Cole, Jamie McWilliam and Roger Morris, with Glen Reid as manager.

Fast forward eighteen years, and in 2006 Trinity are again Irish champions, and this time they're racing in the Student Yachting World, staged as usual at Hallowe'en, and on that occasion at Lorient. They won. By 2008, Irish university interest in the SYWoC is growing every year, and taking part in it is regarded as the peak of our inter-collegiate sailing. That year, Cork Institute of Technology with Nicholas O'Leary as skipper are Irish champions, and they go on to win the SYWoC at La Trinite, giving it an even higher level of national interest back home.

The story since 2008 is part of Irish sailing lore, and UCD's very thorough and successful campaign towards this year's victory is eloquent testimony to the remarkably high level of university sailing in Ireland. This is good news morning.

WILL YOUR BOTTOM LOOK BRIGHT ENOUGH IN THIS?

One of the interesting points to emerge from this week's report into the capsize of Rambler 100 in last year's Fastnet, and the subsequent successful rescue of her large crew, is the suggestion that boats which are liable to invert might usefully have their bottoms coated with high visibility paint.

Rambler 100s upside down hull was hard to spot. Photo: Team Phaedo

For all her great size, the capsized Rambler was remarkably difficult to spot on that grey evening, as her upturned white hull was easily mistaken for a breaking wave.

It sounds like a neat idea, but some agreed definition of boat that is likely to capsize would be a necessary starting point. After all, having a dayglo orange bottom will amount to a statement that your boat is pushing the envelope of lightness and exceptional ballast leverage to the absolute limit, upon which all old salts will say that it's damned unseamanlike, and shouldn't be permitted out of the harbour in the first place.

Then too, which particular shade of dayglo would sir or madam prefer? While extremely useful and indisputably life-saving, when considered purely as colours they're all horrible - in fact, the more horrible, the more effective they become.

Time was when all sorts of notions attached to the different colours of anti-fouling bottom paint, and as most of them change in shade as the season progresses, all sorts of debates are possible on which is the more effective, and at what time in the year.

In the old days, the feeling was that only red anti-fouling was effective – it was something to do with the lethal chemicals which could be successfully incorporated in red. Black was also supposed to be okay, but not blue, and – surprisingly – not brown, despite its relative closeness to clean copper. But of course green like weathered copper was and is much approved – it's what I use myself, but it has to be admitted that's mainly because I simply like the look of it.

One colour which used to be regarded as wellnigh impossible was white, which made it a challenge for amateur chemists. Back in the day when boats were still kept in Ballyholme Bay, I can remember as a kid that the annual launch of the little keelboats of the Bay Class used to see the slipway area kept clear for one boat which would arrive without the anti-fouling already applied. She would be set up ready for launching at the top of the slip, and then the owner would arrive at high speed on his bike, with the carrier loaded with cans of white anti-fouling to his own recipe which he'd been mixing at home in the kitchen, This anti-fouling would be applied in jig time, and the boat then was hurled down the slip into the water, as the magic brew was supposed to lose its potency in fresh air even more quickly than standard anti-foulings.

It looked very smart - white topsides, red boot-top, and white bottom – but the boring boats with the red anti-fouling were always winning by mid-season. But then, in those days antibiotics weren't part of everyday life. Today you'd be regarded as anti-social and an ecological hooligan if you put veterinary anti-biotics into your anti-fouling, but it works.

And I'm told essence of horseradish works quite well too. But this seems to be taking us away from the subject of the colour of boats' bottoms for safety purposes. So maybe we should be talking with our neighbourhood whales. Seafaring lore would have it that whales tend to attack boats with white or red bottoms, but will leave blue, black or green alone. So what are whales likely to make of the heroically revolting dayglo lime, let alone the standard dayglo orange?

Round Ireland's Enhanced Status, & Two Centenarians Strut Their Stuff

#sailing – With so many major international events descending on Irish sailing throughout the 2012 season, it's inevitable that our own home grown classics slipped quickly from the headlines. Yet now, as we see the national programme winding down towards the Helmsman's Championship in October, an appraisal of the summer's highlights shows that the Round Ireland Race from Wicklow has enduring significance.

Denis Noonan and his organising team stick doggedly to the task of keeping this 704- mile challenge in place, and in 2012 they achieved a major breakthrough in getting the round Ireland the same points weighting as the Fastnet Race (which is held in alternate years) in the annual RORC programme, which is as near as we get to a Northwest Europe Offshore Championship.

Thanks to this enhanced status, for the first time there were more overseas boats than home grown entries. In the contest for first place, defending round Ireland title holder Piet Vroon from the Netherlands with his superb Ker 46 lost out by just 12 minutes to father and son team Bernard and Laurent Guoy of France with the 39ft Inis Mor.