Displaying items by tag: Spit Bank

Spit Bank Lighthouse, Cobh, Cork Harbour Undergoes Maintenance Work

#spitbank – The Spit as it is known locally is one of the most well known and distinguished marks in Cork Harbour and greets every vessel passing between Whitegate and Spike Island heading upwards past Cobh writes Claire Bateman.

On passing the Spit last Sunday it was noticed the structure was covered from top to bottom with scaffolding. Two ships in attendance, obviously support vessels, for the ongoing work. One was called 'The Spit Bank' and the other 'The Spike Island'. Obviously renovation work is taking place and no doubt we will see a newly painted and gleaming structure emerge when the work has been completed.

Located to the to the south of Cobh, the Spit is set at the end of a long mud bank marking a ninety degree turn in the shipping channel. Its peculiar form and design make it a striking addition to the maritime heritage, as it differs greatly from the more traditional stone-built lighthouses which are found along the south coast.

The man behind this curious structure, Alexander Mitchell (1780-1868) was quite extraordinary. Born in Dublin, his family moved to Belfast while he was still a child and he was educated at the Belfast Academy where he showed great mathematical aptitude. His eyesight failed during his teenage years and he was blind by the age of twenty- three. Amazingly his blindness did not prevent him from becoming a pioneering self-taught engineer.

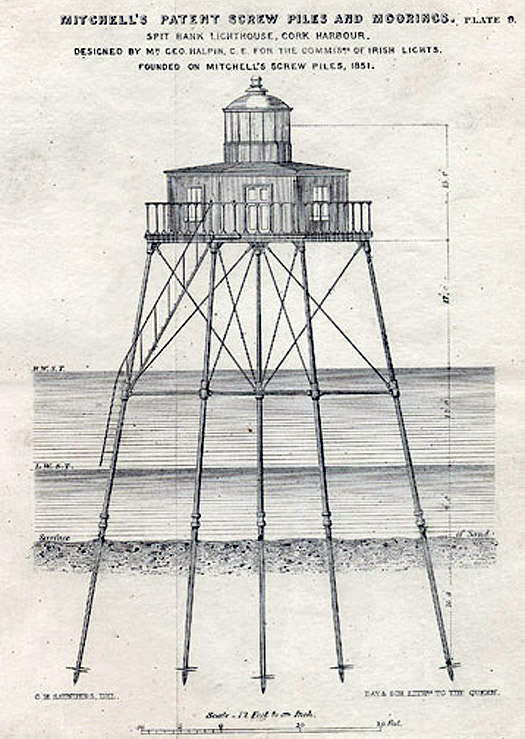

Mitchell patented the "Mitchell Screw Pile and Mooring' in 1833, a cast iron support system which allowed for construction in deep water on mud and sand banks. Apparently inspired by the domestic corkscrew, its helical screw flange c ould be used for difficult shifting foundations on a broad range of structures and its potential was realized in a broad range of projects: lighthouses in Britain and Ireland as well as more than 150 lighthouses in North America; piers such as in Courtown, Co. Wexford and the impressive pier at Madras, bridges and viaducts on the Bombay, Baroda and Central India Railway: and also for the telegraph network in India. Mitchell went on to apply the same technology to propellers and patented the screw propeller in 1854.

Lighthouses using this innovative system were built under Mitchell's supervision at Maplin Sands in the Thames Estuary in 1838; Wyre in Lancashire in 1840, Belfast Lough in 1853 and Dundalk in 1855. The foundations for the first lighthouse, Maplin Sands, were sunk in the incredibly short period of nine days. Before Mitchell's wonderful invention, floating lights had been used where a traditional lighthouse was not possible. Floating lights were not ideal as the movement of the light ship caused great variance in the light's location during storms, and floating lights could brake from their mooring, causing havoc for mariners.

An unlighted buoy had previously marked the commencement of the spit bank near Cobh, but Cork Harbour Commissioners required a more notable structure to take its place. Mitchell won the commission to construct the new lighthouse for £3,450, and moved with his family to Cobh (then Queenstown) in 1851, renting Belmont House overlooking the harbour. He immediately set about engaging workmen, testing the ground and examining the iron for the piles and wood for the house. His son and grandson laid the piles for the lighthouse, with regular inspections from Mitchell, while he oversaw the construction of a timber house on shore. During his fifteen months at Cobh, Mitchell took trips into Cork City during which he met with academic staff at the university and forged a friendship with the great mathematician, Boole. The light was exhibited for the first time two years later, while a foghorn was added in the 1890s. Set out to sea with no room for living accommodation, a principal and an assistant keeper lived in rented accommodation in Cobh.

The original drawings of Cork Harbour's Spit lighhouse. Image courtesy of Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht

Incredibly, accounts survive of Mitchell personally overseeing construction, taking trips out to his lighthouses in small boats, even on rough seas and on occasion falling overboard, going up and down ladders, crawling along planks and examining the wood, iron and rivets. At times he rallied the workers' spirits, leading them in sea shanties. Through touch he checked the quality of the iron work, sometimes noting flaws which had escaped the workers' and foreman's eye. One worker is recorded as exclaiming 'Our master may say what he pleases, but I'll never believe that he can's see as well as thee or I'. Mitchell was made an associate of the Institute of Civil Engineers in 1837, and was elected a member in 1848, at which time he received the Telford silver medal for the invention of the screw pile. He was awarded the Napoleon Medal from the Paris Exhibition in 1855.

The Spit Bank Light Lighthouse remains an iconic structure in Cork Harbour. Described by some as a giant spider in the sea, its curious form and design has attracted much comment and curiosity for the past 150 years. Thanks to the endeavours of this truly gifted inventor and dedicated Engineer, countless lives have been saved at sea.