Displaying items by tag: solo sailing

Barnacle growth was the root cause of Golden Globe Race Finnish skipper Tapio Lehtinen's slow solo circumnavigation but the 110-day difference between his and Race winner Jean-Luc Van Den Heede's time was definitely enjoyable.

"I have certainly got my money's worth from the entry fee." Tapio had joked with Race organiser Don MacIntyre before his return to Les Sables d'Olonne at 20:21hrs on Sunday. "This is the best-organised race I have ever taken part in...And the most selfish thing I have ever done... It is the fulfilment of a life-long dream...I'm not enrolling myself just yet, but yes, absolutely, I would do it again!" the 61-year-old from Helsinki said at his press conference today.

"Yet asked what was the lowest moment in the race, the answer appeared to cover several months. "I had been sailing neck-and-neck with Istvan Kopar across the Indian Ocean when suddenly he started to get away. I thought there must be something wrong - perhaps a fishing line caught in the propeller - and dived overside during a calm spell before the Hobart film drop to investigate. It was not a rope or net, but barnacles growing all over the hull. When I first saw them on the bottom, I knew my race was over."

Other skippers had taken the opportunity to clean their hulls during their compulsory 24 hour stop in Tasmania, but by the time Tapio and his Gaia 36 Asteria reached Storm Bay Australian authorities had put a stop to it. Careening hulls had to be undertaken beyond the 200-mile territorial waters.

Tapio readily admits to an aversion to sharks, so when he prepared to dive overside during a calm period after leaving Tasmania he recalled "I was tying my improvised boarding ladder to the boat in preparation of diving overboard and spotted this huge shark swim alongside the boat - and that was the worst day of my life."

Tapio was accompanied the last 10 miles to the finish by Bernard Moitessier's famous yacht JOSHUA a French entry in the original Golden Globe Race 50 years before. "I sense the smell of Tahiti in Les Sables" Tapio shouted across in reference to Moitessier's decision to foresake the success of finishing by continuing towards a second circumnavigation 'to save my soul' as he put it, before finally dropping anchor off the Pacific island.

Solo Sailing in Irish Waters

I enjoyed watching world sailing history being made this week as 73-year-old Jean-Luc Van Den Heede became the oldest man ever to complete and win a solo non-stop round-the-world race. After 212 days alone at sea he won the Golden Globe Race, finishing in Les Sables d’Olonne in France from where he had started last July and which is also his home port.

I enjoy a little bit of solo sailing myself and, considering the number of top solo sailors from France and the races which start from there, the sport and that section of it get a lot of support.

Watching the big blue spinnaker push Jean Van Den Heede in his 36-foot. Rambler, across the finish line on Tuesday morning in a turbulent sea, accompanied by a flotilla of boats, with hundreds of spectators ashore, I thought - “that should make a point about ageism and underline that sailing really is a “sport for all ages…”

The Golden Globe Race marked its 50th anniversary and the single-handed French Figaro Race, including Irish sailors Tom Dolan and Joan Mulloy will mark its golden jubilee in Irish waters this Summer, with the opening leg of the three-race series from Nantes to Kinsale and a start from Kinsale to Roscoff. Other Irish solo sailors have also shown their abilities internationally.

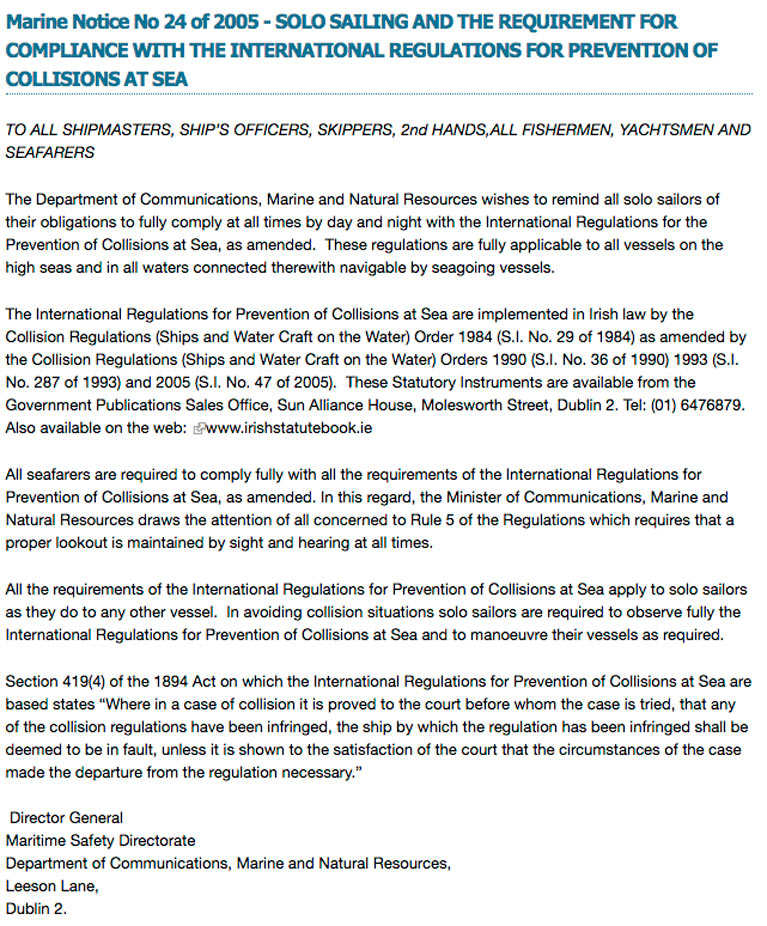

"solo sailing here is still subject to Marine Notice No.24 issued in 2005"

But solo sailing here is still subject to Marine Notice No.24 issued in 2005, thirteen years ago, warning about solo sailing, which is still in effect. At least when I searched the Department’s website this week, I couldn’t find any indication that it had been withdrawn.

Marine Notice No.24 issued in 2005

Marine Notice No.24 issued in 2005

It was controversial at the time, being interpreted as imposing a ban on solo sailing,, though it didn’t say exactly that. It warned about the requirement under the ColRegs – the International Regulations for Prevention of Collisions At Sea to “keep a proper lookout by sight and hearing at all times….”

I like a bit of quiet solo sailing myself aboard my Sigma 33 Scribbler in Cork Harbour and I’m very careful to keep a proper lookout, as there are a lot of commercial shipping movements in the harbour which have right-of-way. I’m also careful of insurance warnings I’ve seen about sailing alone. I’ve met like-minded sailors on the water and seen some racing solo when they couldn’t get crew.

Contrasting that with what I heard Tom Dolan describe in his series of club talks, makes me marvel at the ability of solo sailors.

Marine Notice No.24 of 2005 took a stern stance if a proper lookout wasn’t kept. The issue seems to be whether single-handers can do so effectively, especially when needing sleep. But one Coast Guard statement said that venturing to sea or on the water alone was “neither safe nor conducive to good seamanship."

The Marine Notice applied to “all vessels on the high seas and in all waters connected therewith, navigable by seagoing vessels.” That would include inshore waters and Cork Harbour and my Sigma is, potentially, “seagoing…”

Safety on the water must be taken seriously and an accident while alone can result in a dangerous situation.

The regulation is a warning about solo boating, including sailing, in Irish waters.

Are you aware of it?

Listen to the Podcast here

Mark Slats Closes to Within 50 miles of Van Den Heede in nail-biting race to Golden Globe Finish

With less than 1,700 miles back to the Golden Globe Race finish in Les Sables d'Olonne, 2nd placed Dutchman Mark Slats has sliced a further 393 miles out of Jean-Luc Van Den Heede's lead In terms of distance to finish over the past 8 days. At 08:00 UTC today, the gap was just 49 miles, Slats having gained 205 miles in the past 48 hours.

Jean-Luc, whose Rustler 36 Matmut has led the Golden Globe Race since passing the Cape of Good Hope and at one stage held a 2,000 advantage, has seen his lead being whittled away ever since the 73-year-old Frenchman suffered a knock-down and sustained damage to his mast during a Southern Ocean storm in the South Pacific in November 1.

Van Den Heede still holds a weather advantage and once passed the influence of the Azores high-pressure system, should be first to benefit from the reaching winds that will give him an easier passage north towards the Bay of Biscay.

But Slats is pushing hard despite a few problems of his own. In a satellite call to Race HQ on Monday, the Dutchman reported for the first time that he ran out of fresh water supplies a week ago, and is now using his emergency desalinator to turn salt water into fresh. It is hard work. An hour of pumping with both hands produces just 750ml of water - barely a cup full. The average daily intake is 2.5litres - 3 hours pumping!

Barnacles

He also reported that during a period of calm three weeks ago he had dived on Ohpen Maverick's hull and completely cleaned the bottom of growth and slime. `'It was perfect" he said yesterday. So imagine his surprise when he dived again five days ago to find the hull infested with barnacles once more. "The biggest are 3.5cm long, but most are about 1.5cms. They are growing all over the hull." His first efforts to clean the bottom again were thwarted by the sudden appearance of a 3.5m shark, but he will use the next period of calm to have another go. "So far, this must have cost me about 50 miles."

Third placed Estonian skipper Uku Randmaa whose Rustler 36 One and All, has also been beset by barnacle growth since crossing the Indian Ocean, is today caught in calms in the South Atlantic, some 3,000 miles behind the leading duo. He dived yesterday, and reported: "I'm swimming with dophins." We hope he recognises the difference between these mammals and their more agressive distant cousins!

800 miles to the South, American/Hungarian Istvan Kopar is making great progress northwards in his Tradewind 35 Puffin, seemingly having overcome his self-steering problems.

As is Finland's Tapio Lehtinen aboard his Gaia 36 Asteria who avoided the worst of one storm last week and is attempting to outrun another today. Now within 1,700 miles of Cape Horn but still beset with barnacle growth, he was making 4.3 knots today. Behind him though is the sceptre of Sir Robin Knox-Johnston's Suhaili catching up in their virtual race round the world. Suhaili's relative position from 50 years ago was 512 miles behind a week ago. Today, the distance is nearer 280!

Igor Zaretskiy postpones restart from Albany

Back in December barnacle growth and rigging issues forced 6th placed Russian skipper Igor Zaretskiy to stop in Albany, Western Australia where a medical examination found a continuation of a heart condition, and he flew home to Moscow for further tests. Would this be the end of his challenge?

The good news is that his doctors and team believe it is not, but time to re-start within the Summer window in the Southern Ocean has run out. Igor's plan now is to restart in the Chichester Class sometime in October, to coincide with the Southern hemisphere Summer and complete what he started. In a statement, he says: “There is a natural and always reasoned rule: fight to the end. Until you see the buoy at Les Sables d’Olonne, the race cannot be stopped”

2022 GGR entrant Robin Davie returned to Falmouth on Saturday four days after he was posted overdue, and largely unaware of concerns for his safety. UK Coastguard had issued an All Ships Alert for his Rustler 36 C'EST La VIE after his brother reported him overdue, which he answered late Friday night. Explaining his delay, Robin said: "Faced with calms and very light head winds, I decided to take a long tack out into the Atlantic and back to test the boat in these conditions. We know that this race is won and lost, not in gale force winds, but when they are light so I used the time to test myself and the boat. Because these boats don't have autopilots and rely on wind-vanes to steer by, we followed the wind on a circuitous route that extended the distance from a 300 mile direct course to nearer 700 miles. I was well out of radio range, and it was not until I was 25 miles SW of the Scilly Isles that I first heard the alert."

Ham radio Net

Sailors have been making use of the amateur Ham radio net for decades. Competitors in the Nedlloyd Spice Race from Jakarta to Rotterdam back in 1979 were surprised to find that King Hussain of Jordan was an avid amateur operator and regular participant on their net. National telecommunication authorities have often turned a deaf ear to unlicensed operators using made-up call signs while at sea. But this may be coming to an end following a warning from one National regulator to a GGR skipper. They warn: "You use an amateur callsign and are making connections with amateur radio operators. The call sign letters are not registered, and thus illegal. I ask you to stop. If you have a legal amateur callsign then I urge you to present it".

Fair warning both to unregistered GGR skippers and to legitimate Ham radio operators communicating with them. In Britain, the Ham Radio net is controlled by OFCOM, which recently revoked more than 500 licences for non-compliance. This includes communicating with unregistered Ham radio operators. The maximum penalty is 6 months in prison, a £5,000 fine and loss of their licence.

GGR skippers have been using this free communication system to gain weather forecasts and maintain contact with their teams, which is allowed under the Race Rules, It is the responsibility of each skipper to ensure that they abide by National and International regulations. Such transgressions may not affect the outcome of the Race unless broadcasts have included position reports of GGR yachts which are not allowed. Should that be proved, then skippers face an immediate 48 hour penalty for the first offence, followed by disqualification.

Are you up for a Celestial Adventure with the 2018 Golden Globe Rce? GGR has partnered with RUBICON3 to send two ex-Clipper 60 yachts across the Atlantic on an adventure sail training and Celestial Navigation training exercise. You can join them and return home as a qualified Celestial Navigator. The first boat is full and only a few spots remain on the second for an end of March crossing. GGR will follow the voyage and profile the crew on Facebook. Susie Goodall was an instructor with RUBICON3 when she first heard about the GGR and they sponsored her sextant. Can you do it? YES YOU CAN! and why not.

British Solo Yachtsman Robin Davie Located

Three days after the UK Coastguard first broadcast an 'All Ships Alert' for British solo yachtsman Robin Davie, the 67-year old sailor made contact late Friday night to say that all was well onboard. He expects to reach Falmouth, his home port, later today.

As Afloat.ie reported previously, Davie, who has completed three solo circumnavigations and is preparing to enter the 2022 Golden Globe Race, was three days overdue on a 300-mile solo cross-Channel voyage from France back to Falmouth. British and French Coastguard services have been broadcasting an 'an all ships' alert since Wednesday morning.

Davie made contact with rescue authorities at 22:00 on Friday saying all was well aboard his 36ft yacht C'EST La VIE and gave his position 25 miles south-west of the Scilly Isles.

"This is fantastic news" said Robin's brother Rick Davie who had begun to fear the worst. "I am so grateful for all the help and publicity provided by the Coastguard services and the media for publicising this.

Details remain sketchy, but it appears that faced with very light headwinds, Davie decided to take one long tack out into the Atlantic well out of radio range and the main shipping routes. rather than zig-zag upwind on the direct route north to Brest and across to Falmouth.

A more detailed account will be published on Monday once Robin Davie reaches his home port.

Alert for British Solo Yachtsman Robin Davie, 3 Days Overdue on 300 mile Passage from Les Sables d'Olonne to Falmouth

Falmouth Coastguard has issued an 'All Ships Alert' for British solo yachtsman Robin Davie, now three days overdue on a 300-mile solo cross-Channel voyage from Les Sables d'Olonne, France back to his home port of Falmouth in Cornwall.

The 67-year old experienced sailor, who has successfully completed three solo circumnavigations, set out from the French port at 10:00 on Saturday 5th January, telling his brother Rick Davie to expect him back last Tuesday. Nothing has been heard from him since.

Davie was reported overdue on Wednesday morning and the UK Maritime Coastguard Falmouth have been broadcasting alerts to all shipping in the area since then. No EPIRB signal has been detected.

Weather conditions have been light and variable for the past week. Davie's yacht, the Rustler 36 C'EST La VIE had recently undergone a complete refit including new mast and rigging, which had been fitted in Les Sables D'Olonne.

Davie had entered the 2018 Golden Globe Race but ran out of time to complete his preparations, and was returning home to Cornwall intending to compete in the next GGR solo round the world race in 2022.

Born in 1951 in St Agnes, Cornwall, the sea has always been in his blood. Davie recalled recently Robin Knox-Johnston's return to Falmouth at the end of the Sunday Times Golden Globe Race in 1969 to become the first man to sail solo non-stop around the world. His school refused to give his class time off to watch the spectacle, but he remembers saying to himself: “I’ll do that one day”.

After serving in the British Merchant Navy for 20 years, Davie competed in the first BOC Challenge Around Alone Race in 1990 in yacht named Spirit of Cornwall, and went on to make his second and third solo circumnavigations in the 1994 and 1998 BOC races. During the 1994 race he was dismasted thousands of miles from Cape Horn and sailed under jury rig around the Cape to the Falkland Islands.

2019 will be a year which will mark the 50th anniversary of the Figaro class, a class now recognised as the top level that there is in offshore sailing. And as Afloat.ie has been reporting from the Paris Boat Show, it's an exciting time for Irish involvement too.

The golden anniversary will be marked by an updating of the boat and following 15 years in service, the Beneteau Figaro 2 will be replaced by the super modern foiling Figaro 3. This levelling of the playing field has attracted almost many of the biggest names in sailing such as Frank Cammas, Michel Desjoyeaux, Armel Le cléac'h and Loïck Peyron.

To guarantee sporting equality each skipper was attributed their boat by drawing numbers out of a bowl during a lottery draw which turned out to be quite a glamorous occasion. Tom Dolan, along with Joan Mulloy, were supported with an Irish contingent which included Jack Roy, president of Irish Sailing.

Olympics in sight

"I bagged number 8 which is good, the Chinese say it’s a lucky one" the young Meath man grinned. "now it's time to get to work and find the necessary finance for the next few years. It's great to be able to start fresh with a new boat against the biggest names in the sport, but as you can imagine it's a big financial investment which means borrowing the price of a fine house over a number of years, but it's like any business, you won't get far unless you take the odd risk. Right now I need to find 80K"

Dolan also talked about his future. “For now I really want to concentrate on the Figaro class for a number of years and arrive at a point where I can perform consistently alongside the best as I did during phases this year. This is key in preparing for a spot on the Irish boat in the 2024 Olympic Offshore Event, there is no better school.”

Read also: How Will an Irish Olympic Two-Person Offshore Campaign for France 2024 take shape?

Irish Sailors, the Golden Globe & Cape Horn After 94 Years

On most coastlines in the world, you’ll invariably hear of some challenging nearby headland being referred to as “the local Cape Horn” writes W M Nixon

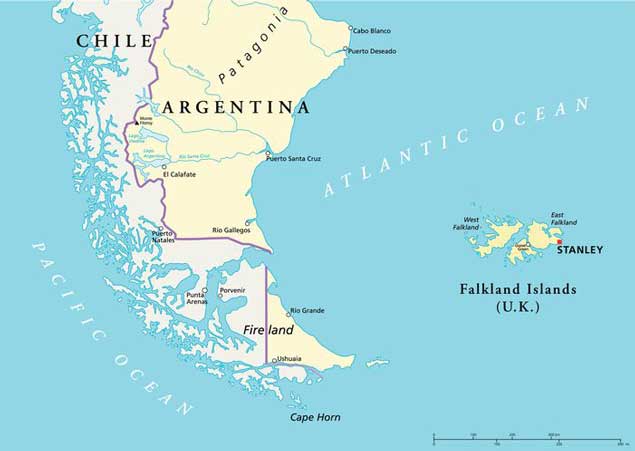

No other promontory worldwide has the same global image. It tells us much about the fearsome reputation of South America’s most southerly point, jutting as it does into the turbulent waters of the Great Southern Ocean where it becomes the Drake Passage, with Antarctica itself not so very far away across some of the roughest seas on the planet.

Cape Horn is always on the oceanic sailing agenda. And at the moment it is top of the list, with 73-year-old Jean-Luc van den Heede of France, leader in the Gold Globe Golden Jubilee Race, rounding it a week ago, while second-placed 41-year-old Dutchman Mark Slats (in a much-depleted fleet) will soon be there, albeit more than a thousand miles astern of van den Heede.

They and the remaining sailors in this challenging re-enactment are following in the wake of solo skipper Robin Knox-Johnston fifty years after he became the first man to sail round the world non-stop in Suhaili, with Knox-Johnston and his little ketch undoubtedly achieving one of world sailing’s truly great firsts.

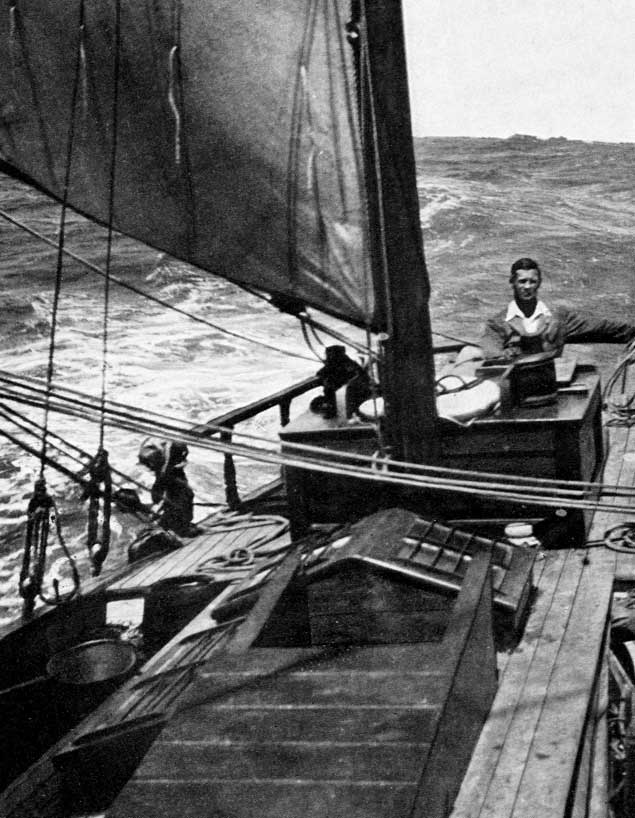

One of world sailing’s most enduring images – Robin Knox-Johnston aboard Suhaili in 1969, approaching the conclusion of his non-stop global circumnavigation

One of world sailing’s most enduring images – Robin Knox-Johnston aboard Suhaili in 1969, approaching the conclusion of his non-stop global circumnavigation

But by the time Suhaili rounded Cape Horn on 17th January 1969, a number of small sailing boats had done so before her, though none in the same epic non-stop world-girdling style. However, some 45 years had elapsed since the first rounding of Cape Horn by a small cruising boat which had crossed the southern reaches of the South Pacific to get there. But though it was hailed afterwards as the great pioneering achievement it genuinely was, at the time those involved seemed to handle it in an almost low key way, however much it may have meant to them personally.

It was the evening of Tuesday, December 2nd 1924 (94 years ago this Sunday) when the small bluff-bowed 42ft gaff-rigged Irish ketch Saoirse, a craft of antique appearance, approached Cape Horn from the west. The weather had been unsettled with winds from several directions, and two days previously, squalls from the northeast had brought flurries of snow despite it being early in the southern summer. But conditions were improving as the Horn came abeam around 2200hrs in the last of the daylight.

Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse departing Dun Laoghaire for her global circumnavigation, June 20th 1923. She returned precisely two years later on June 20th 1925, after becoming the first small craft to run down her easting in the Great South Ocean from New Zealand to round Cape Horn. Photo: Irish Times

Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse departing Dun Laoghaire for her global circumnavigation, June 20th 1923. She returned precisely two years later on June 20th 1925, after becoming the first small craft to run down her easting in the Great South Ocean from New Zealand to round Cape Horn. Photo: Irish Times

With the onset of the short southern summer night with its brief darkness, the wind settled in the north, and the little ship made steady progress. By noon on Wednesday in fine conditions, she had made good 140 miles in 24 hours, aided by a favourable current of at least one knot. Superb visibility enabled the ketch’s crew to admire the massive scenery along the rugged coast as they shaped their course to pass eastward of Staten Island. The wind then drew fresh and favourably from the southwest, and despite progress being slowed by their vessel’s fouled bottom - for they had been at sea for more than 40 days since leaving New Zealand – by Saturday December 6th they were moored in Port Stanley in the Falkland Islands.

By being so far south in totally exposed waters, Cape Horn is often a huge challenge for small sailing craft

By being so far south in totally exposed waters, Cape Horn is often a huge challenge for small sailing craft

In rounding Cape Horn, the ketch’s amateur skipper Conor O’Brien (1880-1952) of Foynes Island on the Shannon Estuary had made the breakthrough towards becoming the first to take a small yacht around the world south of the Great Capes, running down his easting across the full width of the far Southern Pacific through everything that the Roaring Forties and Screaming Fifties could throw at him.

He faced it with some confidence, as his little vessel had successfully negotiated several ocean storms during her long passage from Dublin Bay. Ironically, it was in the warm and sunny latitudes of the Canary Islands that they had experienced one of their most severe tests, logging a day’s run of 185 miles while driving hard in rough seas in a sharp gale of the northeast trade winds.

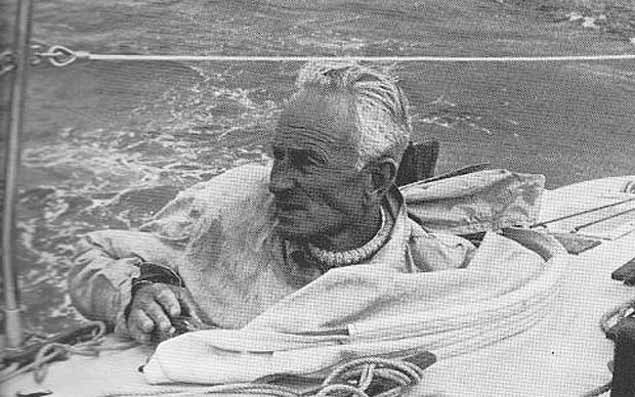

Conor O’Brien was at his most content far at sea, helming Saoirse in markedly relaxed style. Although a “bluff-bowed little vessel”, as indicated here, Saoirse was well capable of good speeds with comfort

Conor O’Brien was at his most content far at sea, helming Saoirse in markedly relaxed style. Although a “bluff-bowed little vessel”, as indicated here, Saoirse was well capable of good speeds with comfort

But O’Brien’s own-designed little ship, soundly built by Tom Moynihan and his craftsmen at the Fisheries School in Baltimore in 1922, proved well able, and continued to log many excellent 24-hours runs. The most severe conditions were experienced between southern Africa and Australia, yet the ketch seemed to lead a charmed life. Although he and his shipmates observed several huge pinnacle breakers caused by intersecting wave patterns which he felt sure would have overwhelmed his vessel had she been caught up in one of those mega-breakers, it never happened, and the long haul across the southern Pacific to curve southward to round Cape Horn was subsequently recounted in an under-stated tone. But then, that was the style of the era and the milieu from which Conor O’Brien had emerged.

O’Brien may have been rewarded with a fairly gentle rounding of the Horn itself, but the very small world of ocean voyagers at the time had no doubt of the quality of his achievement. Although Joshua Slocum in Spray had negotiated his way westward from the Atlantic to the Pacific through the channels north of Cape Horn some 28 years earlier, the weather he’d experienced, coupled with the historical stories from the crews of much larger sailing ships which had succeeded in rounding the Horn – for many failed in the attempt – left no doubt about the extremely changeable and often ferocious conditions which were central to the challenge O’Brien had faced.

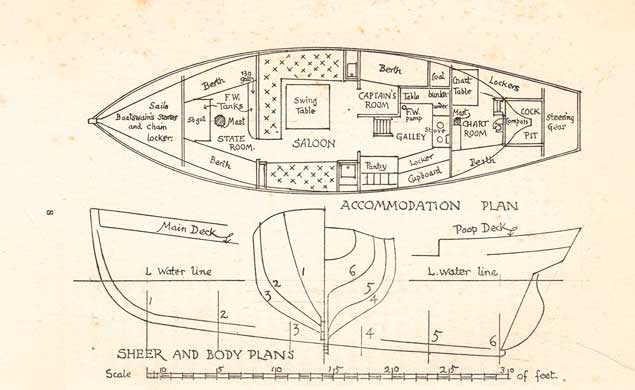

Conor O’Brien designed Saoirse himself, and while she was basically of old-fashioned style, she was way ahead of most boats of the time in having the galley well after in the area of least motion

Conor O’Brien designed Saoirse himself, and while she was basically of old-fashioned style, she was way ahead of most boats of the time in having the galley well after in the area of least motion

For circumnavigator sailors from Europe, once you’ve rounded Cape Horn and returned to Atlantic waters, there’s a reassuring feeling of being on the home stretch, for all that there are ten thousand miles still to sail. Certainly O’Brien and his crew of two became so relaxed that they spent six weeks in the Falklands over the Christmas period, becoming so much part of the local community that a crew-member married a local girl and much of Saoirse’s subsequent voyage northward through the Atlantic was made with just two on board.

Yet although it all continued to be done in a low key style, O’Brien was no slouch when publicity opportunities arose, and he returned to Dun Laoghaire on Saturday June 20th 1925 – two years to the day since he departed – in order to facilitate a rapturous welcome. Dublin Bay Sailing Club even cancelled their Saturday racing programme so that their members could join the fleet welcoming Saoirse home.

For most of the voyage, however, Saoirse and her crew were totally out of contact, and could get on with traversing the oceans in traditional lone ship style. And 45 years later, there were long periods in 1968-69 when Robin Knox-Johnston’s location with Suhaili was a matter of speculation rather than precision – it was something of a surprise when the battered but unbowed little ketch appeared in the distant approaches to Falmouth to claim an indisputable “first”.

But today, a constant flow of information in every shape and form is central to any major oceanic sailing event. The Golden Jubilee of the Golden Globe is supposed to be a retro event in which the participants sail old-style boats of closed hull profile using only the technology available in 1968. But the demands of the 21st century with its multiple communication technologies means that the outside world knows almost everything that is going on in this nine month saga.

Thus when Jean-Luc van den Heede had passed Cape Horn a week ago, it so happened that the AGM of the Old Cape Horners Association was being held in England’s historic naval harbour of Portsmouth, and they were provided with a radio linkup with the 73-year-old Frenchman who revealed that it was in fact his tenth rounding of the Horn, and his most recent visit had been during a cruise in the area when they’d landed at Cape Horn island’s semi-sheltered bay, and had gone visiting with the lighthouse keepers for all the world like cruisers of yore making their way along the west coast of Ireland or through the Hebrides.

Image of a great seaman – the 73-year-old Jean-Luc van den Heede. He has completed his tenth rounding of Cape Horn, leading the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee Race. On his ninth rounding, he was cruising, and he and his crew went ashore and visited the lighthouse keepersThis almost light-hearted approach to the realities of Cape Horn is classic van den Heede, for in order to still be in the lead in the Golden Globe, he had to survive a knockdown four weeks ago which was so violent that it caused the through-mast bolt supporting his lower shrouds to cut its way downwards through the mast extrusion, leaving the vital lower shrouds dangerously slack.

Image of a great seaman – the 73-year-old Jean-Luc van den Heede. He has completed his tenth rounding of Cape Horn, leading the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee Race. On his ninth rounding, he was cruising, and he and his crew went ashore and visited the lighthouse keepersThis almost light-hearted approach to the realities of Cape Horn is classic van den Heede, for in order to still be in the lead in the Golden Globe, he had to survive a knockdown four weeks ago which was so violent that it caused the through-mast bolt supporting his lower shrouds to cut its way downwards through the mast extrusion, leaving the vital lower shrouds dangerously slack.

For a while it looked as though he’d have to divert to Chile for repairs, but somehow this doughty veteran got aloft and cobbled together a repair which held together has now got him round Cape Horn and on to what is admittedly the longest homeward stretch in the world. But his performance is impaired, and he usually has three reefs in the main when only two would be needed were all the rig in full health.

Van den Heede’s Rustler 36 Malmut before the race – the problematic through-mast bolt and tang for the lower shrouds is visible below the lower spreaders

Van den Heede’s Rustler 36 Malmut before the race – the problematic through-mast bolt and tang for the lower shrouds is visible below the lower spreaders

This has meant that second-placed Mark Slats of The Netherlands has been closing the gap, but as van den Heede was an astonishing 1470 miles ahead when his rig damage occurred, Slats has to steadily outperform him by 20% in order to be first back to les Sables d’Olonne in 2019, and since van den Heede got into the Atlantic, the Slats rate of gain has slowed.

Race Tracker here

Both van den Heede and Slats are racing Rustler 36s, a slippy Holman & Pye designed sloop of 1980 which fits neatly into the retro requirement of being a 36ft production design of 1980 or earlier with the specified closed profile, even if in the Rustler 36’s case it does result in a transom stern with a very steeply sloping rudder and a propeller in a large aperture cut from the rudder, which must make them the very devil to handle under power in astern, or indeed under power in any confined manoeuvring situation under power, where prop thrust is often the key to doing the job.

Mark Slats’ Rustler 36 Ohpen Maverick with the steeply-raked ransom and sloping rudder much in evidence

Mark Slats’ Rustler 36 Ohpen Maverick with the steeply-raked ransom and sloping rudder much in evidence

This is probably not remotely of interest in the Great Southern ocean, but as Tim Goodbody so brilliantly revealed with his J/109 in Dublin Bay last weekend, a boat which has an easily-accessed stern-boarding system and handles confidently in astern under power is a very effective rescue machine in a man-overboard situation.

But that’s another topic to which we’ll return some day. Meanwhile, the reality was that the most popular design which turned up to start the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee was the Rustler 36, something of a surprise to casual observers as most folk had initially thought the response would be something nearer Suhaili, and ketch-rigged too.

But as it happens, the one Suhaili sister-ship which was allowed in under special dispensation, Abilash Tomy’s Thuriya from India, and one of the few other ketch-rigged boats, our own Gregor McGuckin’s Biscay 36 Hanley Energy Endurance, were both dismasted in September in the mother of all storms in the middle of the southern Indian Ocean.

Gregor McGuckin – he was dismasted after being rolled 360-degrees in an exceptional storm in an area of the Southern Indian Ocean where Conor O’Brien had noted the power of multi-directional cross seas to build freak waves

Gregor McGuckin – he was dismasted after being rolled 360-degrees in an exceptional storm in an area of the Southern Indian Ocean where Conor O’Brien had noted the power of multi-directional cross seas to build freak waves

Their skippers were successfully retrieved by a French Fisheries Patrol vessel while McGuckin was in the midst of an heroic effort to get to the seriously-injured Tomy under jury rig. But despite promises that Thuriya would be retrieved by the Indian Navy and restored to seagoing standard, she still seems to be out there and virtually not moving at all. This suggests that she is still lying to her broken rigging, whereas McGuckin’s boat is now nearly 400 miles away nearer Australia, as before his controlled retrieval and passage towards Tomy under jury rig, he succeeded in cutting adrift all the broken spars and rigging, and the former ketch has sometimes been drifting at 1 knot and more.

The experience of McGuckin and Abilash in that “perfect storm” is of added interest in that it happened in the area of ocean where Conor O’Brien saw his ultimate breaking crest. The wind strengths were nothing like the horrific power which assaulted Tomy and McGuckin, as at the time Saoirse was running in her surprisingly speedy style before “a moderate gale” (as they used to say), and O’Brien and his helmsman observed a large waving moving along with them maybe about a mile away.

There were marked cross seas running at the time – a significant factor recorded by Gregor McGuckin – and they went to work on this big wave until it peaked out like the Matterhorn or Mount Fuji, an absolutely extraordinary pinnacle of water which then collapsed in hundreds of thousands of tons of breakers and spume.

Neither O’Brien nor his shipmate said a word to each as this all-powerful force of nature manifested itself, but afterwards in his deck log he noted that had Saoirse been caught up in it, she and her crew would have instantly been goners. As for the professional seaman who’d been helmsman at the time, as soon as they reached port in Australia, he went ashore and wasn’t seen again. It greatly annoyed O’Brien, as this was the only helmsman other than O’Brien himself who had shown he could get Saoirse to perform to her best, and O’Brien had hoped that in due course the situation would arise where their combined efforts would see Saoirse achieve the 200 miles day’s run of which he was convinced she was capable.

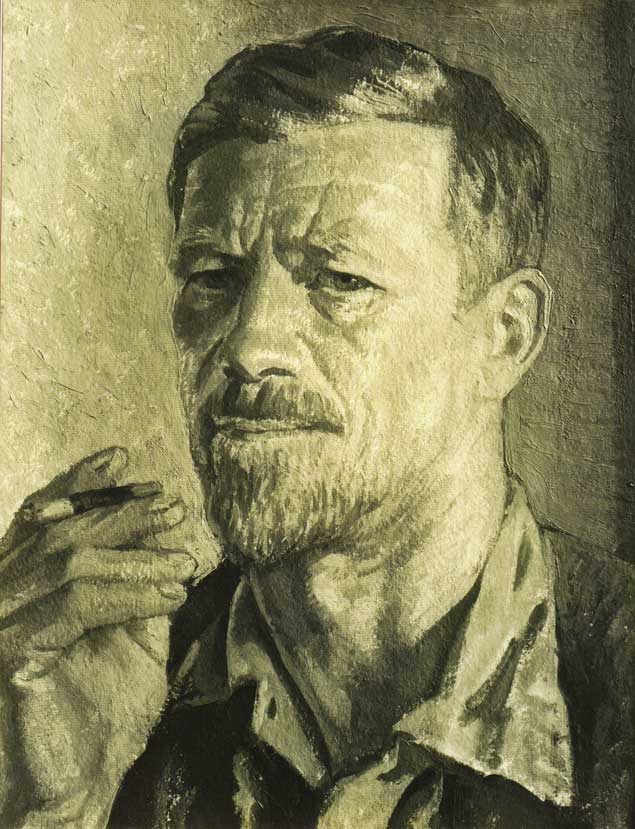

Conor O’Brien as portrayed by his wife, the artist Kitty Clausen

Conor O’Brien as portrayed by his wife, the artist Kitty Clausen

He had many crew changes, but despite that and other difficulties, his underlying intention to sail home via Cape Horn was maintained. Ninety-four years ago on Sunday, it was achieved - a simple and beautiful historical fact of small craft ocean voyaging.

Today, the realities of the Golden Globe Golden Jubilee race underline the remarkable nature of what Conor O’Brien and Saoirse made into reality. He may not have been single-handed, but his crew of two were of limited experience, the boat was of extremely primitive type by today’s standards, and the elements of the unknown in what they were undertaking were beyond calculation.

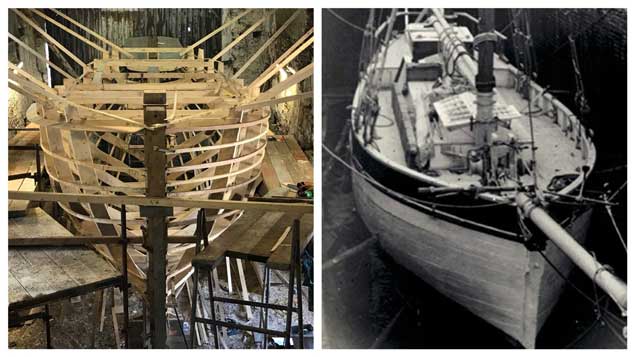

Now that we know so much more about Cape Horn and the conditions which may be experienced in sailing past it, O’Brien’s feat with Saoirse in 1924 becomes that much greater. He may have died on Foynes Island in 1952, but Saoirse has lived on, and she is currently being re-built by Liam Hegarty at his Oldcourt Boatyard near her birthplace of Baltimore. In 2020, Saoirse will sail again, and we will wonder anew at the achievement of the great pioneering sailor of Limerick.

Saoirse being re-built in Oldcourt (left) and as she was in the 1930s after her global circumnavigation of 1923-25. Photos Gary MacMahon

Saoirse being re-built in Oldcourt (left) and as she was in the 1930s after her global circumnavigation of 1923-25. Photos Gary MacMahon

Supporting Ireland’s Solo Sailing Stars

For most participants, sailing is a team effort – we sail as part of a crew in a reasonably sociable mutually-supportive environment. Yet increasingly the best-known sailors are those who compete solo. While we’re naturally interested in the great sailing commanders leading formidable teams which will include many specialists such as rock-star navigators and tacticians, our human feelings are more readily drawn to the lone sailor, whose ultimate success or failure has just one very human focal point. W M Nixon reflects on the current crop of Irish sailors noted for going it alone.

Ireland’s Tom Dolan heads off towards St Barth in the Caribbean tomorrow from Concarneau in Brittany with his shipmate Tanguy Bouroullec, racing in their Figaro Smurfit Kappa-Cerfrance westward across the ocean in the Transat AG2R La Mondiale. Yet although it’s a two-handed race, we are mostly aware of the crew of Smurfit Kappa-Cerfrance as significant solo sailors in their own right, with Bouroullec fourth and Dolan sixth in a fleet of 54 boats in last year’s single-handed Minitransat.

"It is Dolan’s achievement which most captures our imagination"

And it is Dolan’s achievement which most captures our imagination, with his dogged determination and what he has attained from a standing start. For although he was one of the most promising young sailors to emerge from the Glenans training system in Ireland, when he decided to commit to a professional and mainly solo sailing career in France back in 2011, he was so very much alone. A boyhood on a family farm in north Meath provides very little training towards making your way in a strange culture in an intensely nautical place where all communication is in French.

Life’s different with a shipmate – Tanguy Bouroullec on the rail and Tom Dolan on the helm as they put in some training for tomorrow’s two-handed Figaro Transatlantic race to St Barth from Concarneau

Life’s different with a shipmate – Tanguy Bouroullec on the rail and Tom Dolan on the helm as they put in some training for tomorrow’s two-handed Figaro Transatlantic race to St Barth from Concarneau

The Figaro two-handers racing off Concarneau last Sunday – Smurfit Kappa-Cerfrance is third from right.

The Figaro two-handers racing off Concarneau last Sunday – Smurfit Kappa-Cerfrance is third from right.

But he stuck at it, he’s now part of the system, and though he is known as l’Irlandais Volant (“the Flying Irishman”), he is verging on having French as his first language, albeit with a very Irish twist to it now and again.

So both he and Bouroullec will be appreciate the presence of a supportive shipmate with shared goals, for both have known the loneliness of the long distance sailor. And it is something which they have had to come through absolutely on their own, for ultimately that is what it is all about - no matter how big or small the shore support team is, and no matter how often your communications are with them, in the end the pressure is on you.

In this increasing emphasis on individual achievement in sailing, it isn’t just the deep sea stuff which sees this pressure being applied. In a country like Ireland in which many people are only aware of sailing when it is high-lighted as an Olympic sport, the way that the national spotlight can focus with unnatural intensity on young solo sailors in the Olympic classes should be a matter of concern.

The national euphoria when Annalise Murphy won her Silver Medal at the Rio Olympics in August 2016 was in some ways scary to behold. Were we really doing so badly in other Olympic sports that winning just one sailing medal was a matter of near hysteria across the land? And beyond that, what sort of pressure might now be put on Annalise and her successors for subsequent Olympics?

“Announced with the headline: It’s over to you, Aoife.”

Well, we got an idea of it right here on Afloat.ie, when Annalise’s decision not to compete in the Olympic classes selection regatta in Denmark in August, in order to concentrate on completing her involvement with the Volvo World Race, was announced with the headline: “It’s over to you, Aoife.”

When life was more carefree – Aoife Hopkins revelling in big waves when she won the Women’s Laser Radials U21 Euros in France last July

When life was more carefree – Aoife Hopkins revelling in big waves when she won the Women’s Laser Radials U21 Euros in France last July

Young Women’s Radial Sailor Aoife Hopkins was immediately brought centre stage in the quest for an Olympic place, and all this at a time when her training programme had been knocked astray by a three week bout of tonsillitis. It was a reminder, were it needed, of just how much an Olympic campaign at any stage is so dependent on everything being precisely as it should be, and being in good health is just one of the key factors.

In Ireland, it’s something of which we’re acutely aware. Back in September 1972, our Olympic Dragon team of Robin Hennessy, Harry Byrne and Owen Delaney racing at Kiel were on top form, the Dragon Gold Cup already won and an Olympic medal highly likely. But then Owen Delaney was struck down by a severe flu-like virus with the entire finely-tuned structure of the Dragon Olympic campaign being knocked off balance, and any medal chances disappeared.

In recent months this year, Finn Olympic hopeful Fionn Lyden of Baltimore was taken ill with two successive viruses which knocked his plans astray, and made him realize how vulnerable a solo international sailor can be. His recovery was literally aided by team support – he was persuaded while still convalescent to sail as a member of the UCC Team in the Inter-varsities Team Racing at Kilrush, and found himself enjoying the experience so much (it helped that UCC won) that the following weekend he was captaining the UCC team in the Student Worlds Selection trials in the J/80s at Howth, and won again with his health restored.

Reflecting on this welcome turn of events, he said that the crowded and cheerful Kilrush event in particular made him realise how much of a goldfish bowl environment the top level solo sailing scene can become, and it had simply put the fun back into sailing to be part of a team again - he was getting his mojo back.

They’re a tough boat to sail – Fionn Lyden in the Olympic Finn

They’re a tough boat to sail – Fionn Lyden in the Olympic Finn

This theme of simple enjoyment from sailing is something which inevitably crops up in the more stressful solo sailing situations. We’ve long since passed the stage where, if your lone venture of whatever sort does not go through some very difficult and unpleasant challenges, then public interest wanes. The outside world needs to know that the “no pain, no gain” element is still a primary factor in their emotional attachment to the lone challenger.

But sports psychologists are in no doubt that if your longtime sense of enjoyment, of delight in sailing, does not continue to manifest itself from time to time - and preferably frequently - then trouble looms.

"The outside world needs to know that the “no pain, no gain” element is still a primary factor"

Currently, one of the best advertisements for the longterm enjoyment of sailing by a solo sailor is to be found with Ireland’s Sailor of the Year, Conor Fogerty. Anyone who followed his victory in the OSTAR last year will be well aware that he went through some horrendous experiences aboard his Sunfast 36000 Bam! But equally you got a sense of joy in sailing when the going was good, and it was all done with real style.

For the first half of this season, Conor is on a new tack. Bam! is currently being shipped back from the Caribbean after her class victory in the Caribbean 600 in late February, but for home use in Howth late last season he acquired a little classic, the Ron Holland-designed 30ft Silver Shamrock which won the Half Ton Worlds for Harold Cudmore at Trieste in 1976.

There are those who would argue that such a historic 42-year-old boat is almost worthy of consideration for display in a maritime museum. But such notions are the last thing on Conor Fogerty’s mind. On the contrary, he sees her as a charming little boat which is a delight to race against more modern boats, maybe surprising them a little now and again. Last weekend in the Dublin Bay ISORA Warm-up Race, Silver Shamrock finished third overall and first in class, while this weekend with the official ISORA Programme under way, the results will acquire a certain edge.

Conor Fogerty’s Silver Shamrock newly arrived in Howth. Under Harry Cudmore’s command, she was Half Ton World Champion at Trieste in 1976, and 42 years later, she can still give a good showing of herself. Photo: W M Nixon

Conor Fogerty’s Silver Shamrock newly arrived in Howth. Under Harry Cudmore’s command, she was Half Ton World Champion at Trieste in 1976, and 42 years later, she can still give a good showing of herself. Photo: W M Nixon

But through it all, Conor Fogerty will be having a fine old time. That’s the abiding impression you get from talking with those who sail with him in fully-crewed races. He’s an inspirational skipper who is having the time of his life leading a crew of friends, yet he is the same man who can re-set his mental attitude to put in a world class solo racing performance.

This tells us something of the level of will-power needed to continue in the solo sailing game. For although at the top level the famous skippers are supported by a complete and well-funded organisation, there are so many aspirants challenging with what is in effect a shoestring operation in every form of solo sailing that support can get spread very thin indeed, and there are inevitably events in which the imbalance of the challenge against the resources to take it on becomes the main story, rather than just the background to who might win the race. And this is arguably the case with the Golden Globe 2018.

"He is the same man who can re-set his mental attitude to put in a world class solo racing performance"

Inevitably, many in sailing have mixed feelings about this summer’s 50th Anniversary re-enactment of the Golden Globe non-stop solo Round the World challenge of 1968. It wasn’t really a race in the first place - the trophy put up by the Sunday Times was for the first boat to return to north of latitude 40 degrees N having sailed un-aided round the planet south of the great Capes from that same point. And an extraordinary selection of boats had started as soon as they were ready to go.

With the limited communications of the time, the skippers didn’t know where their rivals were, and for a long period the leader was expected to be France’s Bernard Moitessier with his steel 39ft ketch Joshua. However, he went into an increasingly philosophical frame of mind as the event progressed, and having passed Cape Horn, instead of turning left into the Atlantic to head north for the finish, he continued on past the Cape of Good Hope and Australia for the second time until he could take a left turn to the islands of the Pacific, where he retreated for a period of reclusive contemplation.

Bernard Moitessier of France with the 39ft steel ketch Joshua was expected to lead the Golden Globe in 1968, but he retired to the Pacific islands for a period of reclusive contemplation

Bernard Moitessier of France with the 39ft steel ketch Joshua was expected to lead the Golden Globe in 1968, but he retired to the Pacific islands for a period of reclusive contemplation

Meanwhile, Robin Knox-Johnston with the much smaller ketch Suhaili was battling gamely on, and in time he was first to finish with a rapturous welcome at Falmouth. He was very deservedly feted. And if sailing gave much to Robin Knox-Johnston in 1968, in the fifty years since he has re-paid it a thousandfold – his generous and imaginative contribution to our sport is beyond calculation.

"And if sailing gave much to Robin Knox-Johnston in 1968, in the fifty years since he has re-paid it a thousandfold"

But as to re-enacting as far as possible the Gold Globe challenge of fifty years ago, it’s something which can evoke reservations among sailors. Re-enactments are difficult enough ashore, but the re-staging of a round the world solo sailing “race” of half a century ago, with an insistence that the boats be not more than 36ft long and of traditional “closed form” type (ie with rudder hung on the back of the keel), plus additional limitation on modern equipment – well, it all begin to make it all seem a bit artificial, rather than a simple return to good old-fashioned basics.

Nevertheless, with the prospect of at least 270 days at sea and the inevitability of sailing on some of the roughest waters in the world, this is a mighty challenge and then some, and Irish adventurer Gregor McGuckin has thrown his hat into the ring with his entry of a Biscay 36 called Mary Luck.

Gregor McGuckin with his Biscay 36 showing exactly the hull shape which is mandatory for the Golden Globe 2018.

Gregor McGuckin with his Biscay 36 showing exactly the hull shape which is mandatory for the Golden Globe 2018.

Gregor McGuckin’s Mary Luck. The Biscay 36 was designed by Alan Hill in 1974, when her closed-form hull profile was already being superseded by fin-and-skeg yachts

Gregor McGuckin’s Mary Luck. The Biscay 36 was designed by Alan Hill in 1974, when her closed-form hull profile was already being superseded by fin-and-skeg yachts

When something as big as this is in prospect, extravagant claims are not helpful, but his supporters are right in claiming that he will be the first Irishman to sail solo non-stop around the world. For as Cape Horn solo veteran Pete Hogan has gently pointed out, Bill King of Oranmore with Galway Blazer II in 1973 was first Irish man to go solo past Cape Horn with Galway Blazer II in 1973, but he had stopped for repairs in Australia. However as the fleet gathers in Les Sables d’Olonne for the start on July 1st (for apparently British ports were disinclined to host it), who or what or when as regards previous circumnavigations will not be top of the agenda, for it will be dominated by this one extraordinary challenge being faced by all entrants.

Bill King of Oranmore on Galway Bay circumnavigated the world solo in 1973 on Galway Blazer II.

Bill King of Oranmore on Galway Bay circumnavigated the world solo in 1973 on Galway Blazer II.

Yet in the Irish sailing context, Gregor McGuckin’s gallant campaign is just one of many solo efforts which deserve our special attention simply because of the solitary nature of what is involved. We may already have mentioned Annalise Murphy, Aoife Hopkins and Fionn Lyden in the Olympic context, but there are also Oisin McClelland in the Finn, and Finn Lynch in the Laser

Leading the charge. Finn Lynch of the National YC doing what he does best, with the British and Russian boats tucked astern.

Leading the charge. Finn Lynch of the National YC doing what he does best, with the British and Russian boats tucked astern.

As for the offshore stuff, we’re still digesting the extraordinary achievement of Enda O Coineen in getting back alone to Les Sables d’Olonne from New Zealand at the beginning of the month, but equally let us remember that while Tom Dolan races off for the Caribbean with his best shipmate, back in France Joan Mulloy of Westport is continuing with her determination to bring herself up to speed in sailing solo in the Figaro.

Then too, up among the IMOCA 60s, Nin O’Leary of Crosshaven has his developing programme which points inevitably to the next Vendee Globe, in which Alex Thomson’s campaign with Hugo Boss will be receiving continuing input from Stuart Hosford in Cork.

All these sailors come up on the radar because they’re in the world of racing. But solo cruising continues to be a significant interest, and sometimes you hear of lone Irish sailors turning up unexpectedly in out-of-the way places, and then slipping away with even less fuss. They’re all different, these single-handers, whether racing or cruising. And for those of us who sail sociably, they and their achievements have a special fascination.

Mayo solo sailor Joan Mulloy successfully completed her first race in the highly competitive Figaro II fleet in France this morning. The Solo Maître CoQ was the first major race of Joan’s 2018 season and the first time her ‘Taste the Atlantic – a Seafood Journey’ branding was revealed.

The race consisted of a two hour ‘inshore’ race where the 24 strong fleet raced in 20 knot plus winds and big seas off the coast of Les Sables d’Olonne. This was then followed by the 245 miles offshore race that took over 40 hours of nonstop sailing to complete. Joan was the only female to complete the race.

Typically, the solo skippers rely heavily on the ‘autohelm’, an electronic self-steering system, to allow them to sleep, cook and trim the sails. Unfortunately for Joan her autohelm malfunctioned before the start of the offshore race and she was faced with a difficult decision to abandon the race or to continue on knowing that she will get virtually no sleep for the entire race. Joan opted to continue on and sacrifice sleep.

“I said I would do the first short leg and see if I could find a solution to get my autohelm working again. It became clear that this wasn’t going to happen, but I made the decision to continue racing. I knew it would be hard to remain competitive without sleep and not being able to leave the helm for more than a few seconds,” said Joan.

The 245-mile course saw the fleet round some stunning islands off the coast of France and return to Les Sables d’Olonne. The skippers battled the elements and saw winds range from 25 knots to almost nothing at all.

Joan added, “I can’t explain how proud I am to have finished my first solo event."

Joan will now return to Lorient to train for her next event.

Countdown for Dubliner to Become First Irish Man to Sail Non-Stop Single Handed Round the World

Gregor McGuckin (31) is attempting the gruelling feat of becoming the first Irish man to sail non-stop single handed around the world using no modern technology in the upcoming Golden Globe Race.

In 150 days, Gregor will set sail from Les Sables D’Olonne, France in what is one of sailing’s most extreme races. Competitors are restricted to 1960s technology meaning no GPS, no FaceTime, no iPod and no Kindle.

As one of the youngest competitors, Gregor will compete against 24 other sailors using just a compass, the moon and stars to guide him around the world.

“To be the first Irish person to sail around the world solo non-stop will be an amazing achievement, but I wholly believe that I have skill and determination to win the entire race,” said McGuckin.

Only 200 people have successfully sailed solo around Cape Horn, but for Gregor the biggest challenge will be surviving 270 days alone at sea and making sure that his boat can withstand the treacherous conditions.

Certainly, McGuckian, if he can complete the voyage, will join the ranks of few Irishmen to complete the solo circumnavigation – with stops and without – as Afloat.ie has previously reported here.

Gregor’s boat is a Biscay 36 Ketch, which is one of the most competitive models permitted.

Gregor’s boat is a Biscay 36 Ketch, which is one of the most competitive models permitted.

“The greatest challenge will not only be surviving without seeing another human being for nine months but finding the funding to make sure my boat is competitive as possible and can withstand the most extreme of storms.”

Gregor will have to carry all his food for nine months and find ways to catch rainwater to drink. He’ll have a sealed box with GPS in case of emergencies, but if he opens it he’ll be instantly disqualified.

There will be no communication with the outside world, only occasional communications with boats within radio distance and a weekly check in with the race centre.

2018 marks the 50-year anniversary of the Golden Globe Race, and only the second time in history that such a race has been attempted.

The new Colin Firth movie 'The Mercy' (released next week) is based on the original Golden Globe Race and follows the tragic tale of Donald Crowhurst. See a trailer for the movie here.

Gregor McGuckin at the helm of his Biscay 36 ketch

Gregor McGuckin at the helm of his Biscay 36 ketch

Golden Globe Race

The Golden Globe Race is a solo, non-stop, unassisted round-the-world sailing race via the three Great Capes of the Southern Ocean.

2018 marks the 50-year anniversary and the second running of the Golden Globe Race when Sir Robin Knox-Johnston became the first person to sail solo non-stop around the world.

This once-off event is unique as race entrants are restricted to using boats and equipment similar to that which was available for the original race in 1968.

During the race Gregor will navigate 30,000 miles solo non-stop without any GPS or other electronic instrumentation and will spend approximately 270 days at sea.

On completion, Gregor will become the first Irish person to complete a non-stop, solo circumnavigation of the world.

Gregor McGuckin

Raised in Goatstown, Gregor began sailing when studying Colaiste Dhulaigh. Originally a passionate windsurfer, Gregor moved to Mayo to pursue a career teaching watersports to children.

In 2013, Gregor moved to the south coast of the UK to train as a commercially endorsed Ocean Yachtmaster.

He’s logged approximately 50,000 miles as a yacht delivery skipper crossing the Atlantic and Indian Oceans many times.

At 31, he will be one of the youngest participants in the Race and will be one of only 200 people who have sailed solo around Cape Horn.

Gregor alongside his 36–foot ketch in Malahide

Gregor alongside his 36–foot ketch in Malahide

McGuckian's Boat

Gregor’s boat is a Biscay 36 ketch, which is one of the most competitive models permitted.

Currently, it is in Malahide Marina, Dublin and is being put through rigorous preparation and trials to ensure it is prepared for the journey ahead.