Displaying items by tag: solo sailing

Ireland’s Tom Dolan currently lies fourth in class as the 62–strong fleet in the 600-mile Mini-Fastnet from Douarnenez in western Brittany goes into its first night, crossing the English Channel to the first mark at the Wolf Rock writes W M Nixon. After that, they pass close close to Land’s End on a routing which keeps the little boats clear of shipping separation zones.

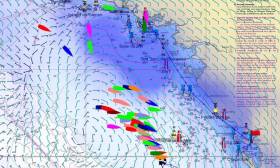

The course for the Mini Fastnet has to take account of shipping zones

The course for the Mini Fastnet has to take account of shipping zones

It’s a two–handed event, and sailing with Dolan on Cellestab.com (IRL 910) is longtime shipmate Francois Jambou. Once again Ian Lipinsky with the ultimate prototype Griffon is the overall leader, but with the breeze mostly from the easterly sector, most of the fleet have been making good progress.

However, once Land’s End has been passed, an obligatory leg northward may see some windward work, while the weather in the days ahead could see much flukier conditions develop. But for now, sailing conditions are wellnigh ideal, and IRL 910 was making 8.2 knots in fourth place as midnight approached.

Tom Dolan Has Good Night Racing in Bay of Biscay

Ireland’s Mini Transat campaigner Tom Dolan has moved up several places in a good night despite difficult racing in the Bay of Biscay in the 55-boat 220-mile Marie-Agnes Peron Trophy from Douarnenez writes W M Nixon.

Having had to contend with unstable nor’west winds to get past the Ile de Groix and on to the southerly turning point down towards Belle Ile, his Pogo 610 (IRL 910, sailing this race as Sellastab.com) was at one stage back in 9th in the 55 boat fleet, but overnight he moved up the rankings, and as of 0700 Irish time this morning was second in class with 98 miles still to race.

Ireland’s Tom Dolan has had a good showing in the overnight racing

Ireland’s Tom Dolan has had a good showing in the overnight racing

They are, however, 98 very challenging miles to sail as they take the fleet up past the Pointe de Penmarch and on out into open ocean to the westerly turning mark well beyond the Ile de Seine before they can head towards the finish in the Baie de Douarnenez.

Once again the leader on the water and heading the Proto division is Ian Lipinski’s remarkable Griffon. She’s perhaps the oddest-looking boat in the entire Mini fleet, but handsome is as handsome does.

Race tracker below:

Tom Dolan Lies Sixth in 220 Miles Sprint

Tom Dolan Shows Consistency Through Tricky Second Night of Mini-en-Mai (Tracker HERE!)

Irish solo skipper Tom Dolan has continued to show exceptional consistency as he maintains his position at the front of the fleet through a challenging second night of the 500-mile Mini-en-Mai in the Bay of Biscay writes W M Nixon.

Low pressure systems are slowly working their way northeast across the Bay of Biscay. While the first day of the race saw winds mainly from the east helping to set a fast initial pace, the slow change in the weather has meant an uneven switch as the wind veers fitfully though southeast to what will eventually be a south to southwest breeze by tomorrow (Friday).

With a belt of rain going through to add to the unpredictable nature of the local winds, it has been an exhausting night of maximizing any small advantages that might fall his way. As of 0830hrs Irish time this morning, he had the satisfaction of knowing that he is now well through the halfway mark, with 214 miles to race to the finish back at La Trinite sur mer, though the main item on the agenda this morning continues to be getting his Pogo 3 Offshoresailing.fr (IRL 910) to the southerly turn off Royan at the mouth of the Gironde Estuary.

It would be easy to say things will get easier after that. But things just aren’t easy at any stage in a race sailed at this level. Currently, his speed is down at 4.4 knots, but it’s sufficient to keep him at second in class and within close company with his nearest rivals Emile Henry and Pierre Chedeville, both also sailing Pogo 3 boats, and battling with Dolan for the class lead by fractions of a mile.

Ireland’s Mini Classe Solo Sailor Tom Dolan With Front Runners Off France (Tracker Here)

After a good start which saw him in third shortly after crossing the line in the 500-mile Mini-en-Mai event for Minitrasat 650s which started today off La Trinite sur Mer on France’s Biscay coast, Ireland’s Tom Dolan is currently rated at eighth on the water in a tightly-packed fleet. Dolan featured in W M Nixon's Saturday blog here.

With his speed building to 11 knots and 489 miles still to sail, he’s racing a course which is neatly divided between coast-hopping in the early and finishing stages, with a long offshore haul heading southeast well seaward of the Biscay shore in the middle.

Track Dolan and the fleet below:

Mini Transat: Fully Booked, One Irish Adventure Sailor in 84–Boat Fleet

Solo Sailor Tom Dolan from County Meath has booked his place in October's Mini–Transat Race from La Rochelle to Martinique.

The sole Irish entry was in Dublin last night to talk about his exploits at Poolbeg Yacht and Boat Club. This will be Dolan's second Mini–adventure having successfully competed in 2015.

For this 2017 edition of the race, organised by Collectif Rochelais pour la Mini Transat, the race will host a full contingent as the number of applicants signed up for the adventure already exceeds the 84 places available. Download the full entry list below.

- The Mini Transat 2017 will set sail from La Rochelle

- Las Palmas de Gran Canaria and Le Marin (Martinique) the stopover and finish venues

- 84 competitors expected on the start line on 1 October 2017

Forty years on from its first edition, the Mini Transat remains on the crest of the wave. A maiden voyage for some, a stepping stone to further sporting challenges for others, the Mini Transat holds a very special place in the world of offshore racing. In an era of new technologies and intensive communication, it is still the only event where each racer is pitted solely against themselves during a transatlantic crossing. No contact with land, no other link to the outside world than a single VHF radio, at times the Mini Transat is a voyage into solitude.

Boats: minimum length, maximum speed

With an overall length of 6.50m and a sail area pushed to the extreme at times, the Minis are incredibly seaworthy boats. Subjected to rather draconian righting tests and equipped with reserve buoyancy making them unsinkable, the boats are capable of posting amazing performances in downwind conditions… most often to the detriment of comfort, which is rudimentary to say the least. In the Class Mini, racers can choose between prototypes and production boats from yards. The prototypes are genuine laboratories, which frequently foreshadow the major architectural trends, whilst the production boats tend to be more somewhat tempered by design.

Racers: from the amateur to the future greats of offshore racing

There are countless sailors of renown who have made their debut in the Mini Transat. From Jean-Luc Van Den Heede to Loïck Peyron and Thomas Coville, Isabelle Autissier and Sam Davies, a number of offshore racing stars have done the rounds on a Mini. However, the Mini Transat is also a lifelong dream for a number of amateur racers who, in a bid to compete in this extraordinary adventure, sacrifice work and family to devote themselves to their consuming passion. Nobody comes back from the Mini Transat completely unchanged. This year, there will be 84 solo sailors, 10 of whom are women! The Mini Transat is also the most international of offshore races with no fewer than 15 nationalities scheduled to take the start.

The course: from La Rochelle to the West Indies via the South face

Two legs are offered to make Martinique from Europe’s Atlantic coasts. The leg from La Rochelle to Las Palmas de Gran Canaria is a perfect introduction to proceedings before taking the big transatlantic leap. The Bay of Biscay can be tricky to negotiate in autumn while the dreaded rounding of Cape Finisterre on the north-west tip of Spain marks a kind of prequel to the descent along the coast of Portugal. Statistically, this section involves downwind conditions, often coloured by strong winds and heavy seas. Making landfall in the Canaries requires finesse and highly developed strategic know-how.

The second leg will set sail on 1 November. Most often carried along by the trade wind, the solo sailors set off on what tends to be a little over two weeks at sea on average. At this point, there’s no way out: en route to the West Indies, there are no ports of call. The sailors have to rely entirely upon themselves to make Martinique, where they’ll enjoy a well-deserved Ti Punch cocktail to celebrate their accomplishments since embarking on the Mini adventure.

Enda O'Coineen Will Not Be First Irish Solo Circumnavigator

The current Vendee Globe Race non-stop round the world is deservedly attracting enough attention without having to make over-stated claims on behalf of some of its participants writes W M Nixon.

The official website is today carrying a story that if Enda O’Coineen can succeed in his plan of sailing his dismasted IMOCA 60 Kilcullen Voyager from Dunedin at the south end of New Zealand under jury rig to Auckland 800 miles away to the north, where a loaned replacement masts awaits, then if he can continue the voyage back to les Sables d’Olonne round Cape Horn he will become the first Irishman to sail solo round the world.

Not so. Noted Dublin marine artist Pete Hogan, who sailed solo round the world in his gaff ketch Molly B, said today that the number of misapprehensions about who was first doing what in the Irish circumnavigation stakes is astonishing.

For instance, when he rounded Cape Horn in the 1990s, he was acclaimed as the first Irishman to do it alone, for of course Conor O’Brien had done it with the crewed Saoirse in 1925. Yet Pete Hogan found it very difficult to get anyone to listen when he subsequently tried to set the record by saying that Bill King of Galway with the junk-rigged ketch Galway Blazer was the first solo, and that was way back in 1973.

The fact that Bill King was a distinguished former British submarine commander may have projected the image of being non-Irish. But in fact he flew both the Irish tricolour and the

British red ensign, and his home was Oranmore Castle at the head of Galway Bay.

Bill King’s purpose-designed Galway Blazer circumnavigated the world solo south of the great Capes in 1973.

Bill King’s purpose-designed Galway Blazer circumnavigated the world solo south of the great Capes in 1973.

Since then, other Irish sailors who have striven to circumnavigate include Declan Mackell, originally from Portaferry but Canadian-based by the time he undertook his voyage in a Contessa 32, with which he returned home to Ireland for a prolonged stay during his circuit.

Another lone circumnavigator, Pat Lawless of Limerick who completed his voyage with a Seadog ketch in 1996 at the age of 70, had hoped to take in Cape Horn, but rigging damage forced him into a Chilean port, and eventually he returned to Ireland via the Panama Canal. But his circuit was definitely completed, and completed alone.

And Pete Hogan believes there may be one or two other Irish lone circumnavigators who have done it without fanfare. For not everyone seeks the kind of publicity which the Vendee Globe inevitably provides.

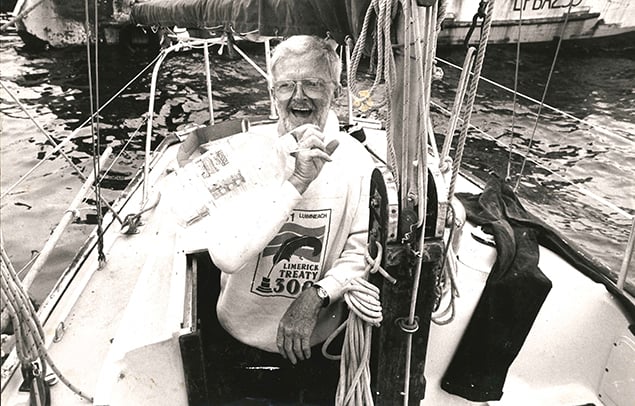

Limerick circumnavigator – the irrepressible Pat Lawless aboard his world-girdling Seadog ketch

Limerick circumnavigator – the irrepressible Pat Lawless aboard his world-girdling Seadog ketch

For many Afloat.ie readers, he was just a silhouetted figure sitting atop a boat waiting to be rescued when Afloat.ie published the story about a solo sailor's rescue off the Wexford coast. Like so many rescue video clips, there was little detail on what had caused the boat to capsize but French skipper Jean Conchaudron's subsequent thank you comment on Afloat.ie to the Irish rescue services shed a lot more light on his remarkable rescue from the Irish Sea.

Conchaudron was voyaging from Newlin, Cornwall to Dublin. His goal was to meet a friend who was coming to Dublin from Iceland. After a few days holidaying in Dublin they would come back with the two boats to Brittany (Perros Guirec).

Jean Conchaudron's Mini 6.50 in happier times

Jean Conchaudron's Mini 6.50 in happier times

But as we now know, none of this ever happened. As a result of 'mechanical failure' Conchaudron's keel fell off and he was capsized in seconds.

'Conditions were quite good, I was on deck, wind was about 15 knots, some swell. The boat capsized in about five seconds'.

'I had my PLB in my trousers, and my life jacket on. I triggered the PLB I have in my pocket. It then took to me about half an hour to be able to make a web of ropes to climb on to the hull, I was pushed up and down by the waves, and it took me a while to secure myself with the rope (the web of rope can be seen on the video). It was not possible to start my boat beacon because it was in the cabin and not accessible.

'I then waited to be rescued. The Rescue 117 Helicopter from Waterford saved me and I spent four days in Waterford Regional Hospital due to hypothermia. Thanks to the Irish recsue services, these guys are heroes'.

Conchaudron says he loves Mini 6.50 type sailing and prefers sailing alone. Despite what happened off Wexford, he believes his boat is 'very safe' and well equipped, as are all the boats of this class with a radio beacon and other safety measures. He participated in the "Mini Transat" in 1987, and other races in France.

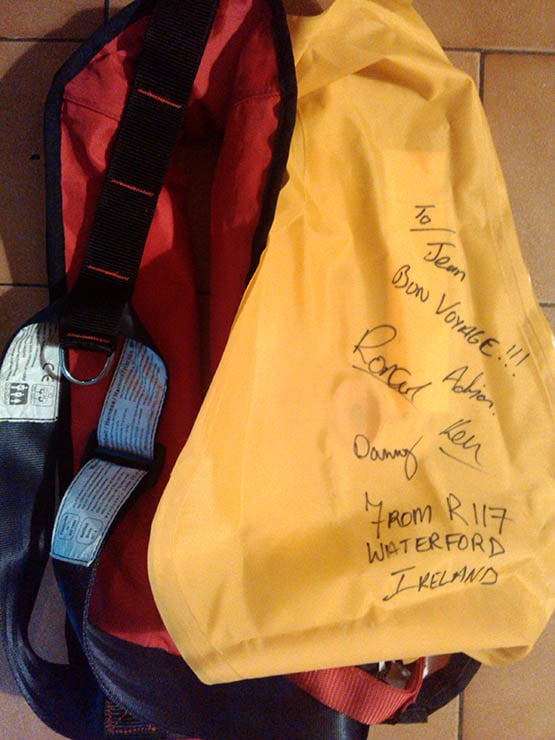

Jean Conchaudron's all important lifejacket signed by his rescuers

Jean Conchaudron's all important lifejacket signed by his rescuers

As far as he knows, the boat is still adrift in the Irish Sea. Conchaudron says the Coastguard is 'keeping an eye on it.' It is his intention to try to get it back, depending on what his insurers say.

'I hope this experience will help other sailors', he wrote on the Rescue 117 Facebook page.

Conchaudron says he has learned an important lesson from the experience and wants to pass it on to other sailors in the hope that it can save other lives at sea: 'Have a PLB in your trousers's pocket, wear your life–jacket, stay afloat, don't sleep and be a warrior to survive'.

Strangford Lough's Andrew Baker 13th in Solo Normandie

Northern Ireland solo sailor Andrew Baker finished 13th in the Solo Normandie race. Baker, from Strangford Lough, is part of the British Artemis offshore team.

British Figaro racer Alan Roberts secured third place, his third top-10 finish of 2016 on Saturday ahead of the Solitaire Bompard Le Figaro in June.

After sailing 284 miles of some of the most challenging French Atlantic coastline, from Granville to Le Havre, Roberts finished the Solo Normandie in third place on Vasco de Gama.

The British solo racer from Southampton was just 17 minutes behind race-winner Alexis Loison (Groupe Fiva) and eight minutes behind Damien Cloarec (Saferail) in second. Fifteen competitors took part.

This podium finish for Roberts follows his 10th place in the Solo Concarneau and 6th in the Solo Maître Coq and it continues his impressive build-up to the Solitaire where he will be looking for a second consecutive top-10 finish overall after coming 9th last year.

Ahead of the Solo Normandie, Roberts was looking forward to tackling a challenging tidal course – at the finish he said the race didn’t disappoint.

“It was cool,” said Roberts on the dock at Le Havre. “We got to play through some interesting tide effects and rocky areas and sail next to some giant lighthouses. It was a great race, and it delivered exactly what I had expected, if not more.”

After rounding the first mark in the top-four boats, Roberts then found himself at the back of the fleet on the first beat after an incident with another boat. Getting very little sleep during a challenging two-day race, he then worked hard to establish himself back with the front-runners.

By the final hours of racing, Roberts was back in the top-five – and he then enjoyed a brisk final run to the finish line, helped by playing the tides at Raz de Blanchard (the famous Alderney Race), to take his podium finish.

“Being one of the first at the Raz de Blanchard is what won the race in the end,” he continued. “The Solo Normandie was pretty difficult and tiring. I had to work really hard to move back through the fleet which has been the story of all of my races this year so far.”

Asked about his feelings ahead of this year’s Solitaire Bompard Le Figaro, Roberts sounded confident: “I’m feeling happy with my speed. These first three races have shown me that I am able to pull back through the fleet when I need to.”

The next British skipper into Le Havre was Robin Elsey aboard Artemis 43 in 7th. Recently returned from the 3,890-nautical mile Transat AG2R La Mondiale, a double-handed transatlantic Figaro race, Elsey threw himself in at the deep end with the Solo Normandie – his first solo race of the season.

“It was a difficult race and I made a lot of rookie mistakes,” Elsey admitted. “I’m just glad I finished it and didn’t come last! After a bad start – I’m never really a good starter anyway – I found myself back with the fleet on the second leg of the race; I managed to claw it back.”

On the challenges of the course Elsey said: “The tides were difficult. Will (Harris) and I entered the Raz de Blanchard at the same time and I ended up sailing away and leaving him behind. I felt a bit bad doing that. But in the end we finished next to each other anyway – that boy is like a bad rash, you can’t get rid of him!”

Staying true to form, Harris was the first British rookie to finish. He was 8th overall and second rookie behind Justine Mettraux (Teamwork), making this Harris’s third rookie podium position of the season, the Harris/Mettraux battle will make for an interesting Solitaire rookie competition.

“That was probably the most difficult of the three races we’ve had so far,” said the skipper of Artemis 77. “There was never a good time to sleep and the tide, the wind and the position of the fleet was constantly changing. You had to stay reactive.

“I’ve learned a lot this season. You take so much away from every race. I go into each race knowing more, but I also come out of the other end having learned more – I think that is the case for all of the rookies. We have a few weeks of training now to get ready for the Figaro,” he concluded.

Next over the line was Academy Alumni Andrew Baker (Artemis 64) in 13th, then rookies Hugh Brayshaw (Artemis 23) in 14th and Mary Rook (Artemis 37) in 15th.

The next race for the rookies is the big one; the 1,425-mile Solitaire Bompard Le Figaro, that starts on 19th June from Deauville.

The Solo Normandie 2016 results

Position/Skipper/Boat name/Time at sea

1. Alexis Loison/Groupe Fiva – 1d, 19h, 34m, 10s

2. Damien Cloarec/Saferail – 1d, 19h, 43m, 50s

3. Alan Roberts/Vasco de Gamma – 1d, 19h, 51m, 10s

7. Robin Elsey/Artemis 43 – 1d, 20h, 17m, 17s

8. Will Harris/Artemis 77 – 1d, 20h, 17m, 45s – 2nd Rookie

13. Andrew Baker/Artemis 64 – 1d, 20h, 59m, 25s

14. Hugh Brayshaw/Artemis 23 – 1d, 21h, 32m, 49s

15. Mary Rook/Artemis 37 – 1d, 22h, 12m, 35s

A French yachtsman competing in The Transat bakerly solo transatlantic race from Plymouth to New York, was forced to abandon the race today after his boat crashed into a container ship.

Maxime Sorel on board the yacht VandB was among the leaders in the 10-strong Class40 fleet, as the boats raced downwind in the northern Bay of Biscay about 90 nautical miles west of Lorient, when he reported a collision.

The boat suffered damage to its bowsprit, forcing Sorel to head to the French port La Trinite sur Mer in Brittany. Sorel is safe and uninjured and the boat’s mast is stable but he is very disappointed to have to retire.

The collision happened in broad daylight and good visibility this morning, in an area of busy commercial shipping off the Brittany coast.

Sorel said he was keeping watch as VandB sailed under spinnaker but he did not see the cargo ship. “I was not sailing particularly fast and I tried to avoid it but it was too late,” said the French skipper as he limped toward the coast.

He said he had two options when he realised a collision was inevitable. Either hit the ship lengthways which risked bringing VandB’s mast down or hit the ship at an angle, helping to confine the damage to the bowsprit. “I’m stressed seeing all these freighters around me,” he added. “I have this image in my head and when I see one, I get stressed about it.”

Sorel is hoping to reach port tomorrow morning. Reflecting on the cruel hand that fate played, he commented: “I’m disappointed. You (the organisers) called me this morning to tell me that I was leading the Class40s and now you call to talk to me about why I am giving up. It’s disappointing to have to retire like this.”

Elsewhere in the Class40 fleet, the sole British entry in the class, Phil Sharp on board Imerys, has been referred to the Race Committee Jury after apparently sailing through an area of water restricted to commercial shipping at Ushant. The Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) off that busy corner of France is strictly out of bounds to the yachts in the race rules.

Sharp has been sailing a superb race in the early stages, regularly holding the lead, but he may face a penalty for the infringement. Contacted on the sat phone he said he had not realised the TSS was out of bounds.

“I was aware of the TSS and I kept well out of the shipping lane, but I wasn’t aware that it was a restricted zone – I wasn’t aware that there was a boundary,” he said. Sharp also revealed that he nearly lost his spinnaker when it detached from the rig as he was down below and ended up in the water behind the boat.

“I looked up one time and the spinnaker was just not there,” he said. “I went on deck to find the whole thing in the water. But it’s fine and not damaged. I managed to get it back and re-hoist it after a couple of minor repairs.”

The Transat bakerly is already featuring some classic battles. At the front of the fleet the two leading Ultimes, Macif (Francois Gabart) and Sodebo (Thomas Coville) are a little more than a mile apart, heading down the Portuguese coast while, behind them in the southern Biscay, a battle royal is developing in the IMOCA 60 class.

The leader by a whisker is the hugely experienced Vincent Riou on board PRB who is just managing to stay ahead of the two leading foiling boats – Sébastien Josse’s Edmond de Rothschild in second place and Armel le Cleac’h’s Banque Populaire in third.

“Everything is fine, but we had to do a lot of manoeuvres during the night – it was a bit complicated, but as expected and I’m pretty happy with my position,” reported Riou earlier in the day. “The conditions are favourable for the foiling IMOCAs and will continue to be for a few days.

“I’m currently sailing under spinnaker in around 12 knots of wind. I’m trying to move quickly, but there is quite a lot of swell and there are still some sail changes to make. I’m staying vigilant, always looking out for the next transition. The weather is pretty nice compared to yesterday’s start and I was able to get some rest this morning. I am in good shape," Riou added.