Displaying items by tag: Hal Sisk

When Hal Sisk of Dun Laoghaire was awarded the International “Classic Boater Of The Year” Award in London on April 12th, the brief outline of his major achievements in preserving maritime heritage may have high-lighted his current project - with Fionan de Barra and Steve Morris – of restoring the Dublin Bay 21 Class. But even a quite detailed outline of his other successes, such as the internationally-awarded restoration of the 1894 Watson cutter Peggy Bawn in 2003-2005, inevitably missed out some other visionary projects like the 1984 Centenary revival of the 1884 Fife cutter Vagrant, and the re-creation of the Dublin Bay-tested (and proven) catamaran Simon & Jude, originally of 1663 vintage.

As to his determination in undertaking the completion and publishing of major works of maritime historical reference, here again the sheer weight of output has overshadowed some works. The definitive guide to the traditional craft of Ireland – published in 2008 – is now a standard reference, but equally the Peggy Bawn Press’s beautifully produced and profusely-illustrated work about the Scottish designer G L Watson – the first yacht designer to function as a stand-alone specialist – is now a book of major international significance. Yet typically it is just another part of the remarkable creative output encouraged and organised over many years by Hal Sisk.

Hal Sisk, Steve Morris and Fionan de Barra Awarded International Classic Boat Recognition in London

Hal Sisk of Dun Laoghaire has tonight (Tuesday) received the International Classic Boater of the Year Award in London for his decades of inspired service to classic craft and sailing history, while his colleagues Fionan de Barra of Dun Laoghaire and Steve Morris of Kilrush Boatyard were also personally awarded - at a ceremony in the Royal Thames Yacht Club - for their exceptional work in the trio’s current shared project, the restoration of the Dublin Bay 21 Class.

Hal Sisk’s involvement with classic craft – which includes his current role as Chairman of the International Association of Yachting Historians - came after an active offshore racing career. He was one of the creators fifty years ago of ISORA in 1971-72, while his first significant vintage project was the restoration of the 1884-vintage Fife cutter Vagrant in 1984.

Many other interests and classic boat types were explored before - in 2003 - he initiated the successful 2005-completed restoration of the 36ft 1894-vintage G L Watson designed cutter Peggy Bawn (built by Hilditch of Carrickfergus), while another avenue of thought was explored with a glassfibre version of the 1890s Dublin Bay Colleen class.

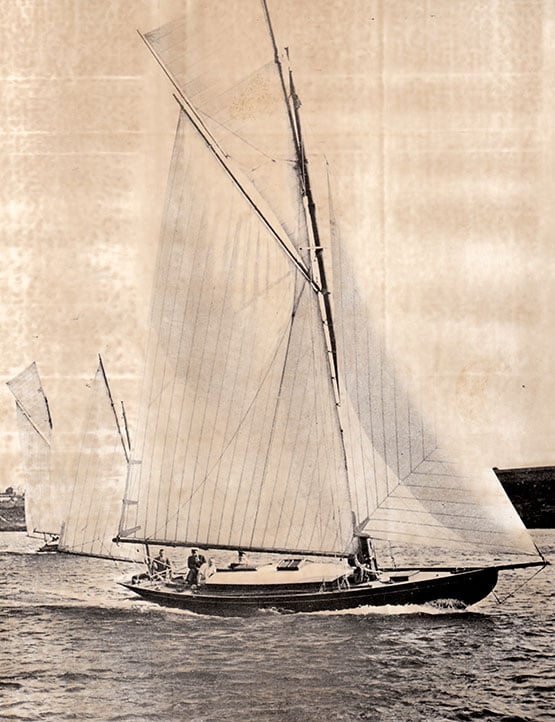

Hal Sisk sailing his first major project, the restoration of the 1884 Fife cutter Vagrant in 1984. Photo: W.M.Nixon

Hal Sisk sailing his first major project, the restoration of the 1884 Fife cutter Vagrant in 1984. Photo: W.M.Nixon

Two other special interests – the glassfibre version of the 1890s Dublin Bay Colleen sailing with the 2005-completed restoration of the 1894 Watson cutter Peggy Bawn. Photo: W M Nixon

Two other special interests – the glassfibre version of the 1890s Dublin Bay Colleen sailing with the 2005-completed restoration of the 1894 Watson cutter Peggy Bawn. Photo: W M Nixon

He served as Class Captain of the Dublin Bay Water Wags (with whom he has actively raced for many years) when the 1887/1900 class finally achieved a turnout of 30 boats on the starting line, and meanwhile he was starting to work with Fionan de Barra, custodian of the 1902-founded Dublin Bay 21s, on developing a meaningful way of restoring the seven boats as a viable proposition to suit contemporary circumstances.

The DB21 project gets under way with Naneen delivered to Kilrush with (left to right) Fionan de Barra, Steve Morris, design consultant Paul Spooner, and Hal Sisk.

The DB21 project gets under way with Naneen delivered to Kilrush with (left to right) Fionan de Barra, Steve Morris, design consultant Paul Spooner, and Hal Sisk.

The re-built Naneen about to launch with (left to right) Steve Morris, James Madigan, Hal Sisk, Fionan de Barra, Fintan Ryan and Dan Mill. Photo: W M Nixon

The re-built Naneen about to launch with (left to right) Steve Morris, James Madigan, Hal Sisk, Fionan de Barra, Fintan Ryan and Dan Mill. Photo: W M Nixon

With four of the re-built boats expected in commission this summer thanks to the work by Steve Morris and his team at Kilrush Boatyard, the dream is becoming reality, and it means that Hal Sisk has now been very successfully involved in restoring classic craft from the three greatest Scottish designers of the “Golden Age” - William Fife, G L Watson and Alfred Mylne.

The re-built Garavogue on her way to winning the first Dublin Bay race of the restored class in September 2021 with three re-built boats contesting.

The re-built Garavogue on her way to winning the first Dublin Bay race of the restored class in September 2021 with three re-built boats contesting.

Yet remarkable as that is in its own right, it is only part of the broad swathe of inspired thinking and varied projects in which Hal Sisk has been involved in his many decades of playing a leading role in the Irish and international maritime scene, not least of them being the guidance through to publication – in 2008 - of the monumental book recording all the traditional craft of Ireland.

Fionan de Barra & Hal Sisk of Dun Laoghaire are "Sailors of the Month (Services to Sailing)" for July

The restoration of all seven original Dublin Bay 21ft One-Designs (the oldest of them date from 1903) is still work in progress. But a major milestone in the process - the Cape Horn of a unique voyage – was safely put astern on Friday, July 30th, when the first three superbly-restored boats sailed back into Dun Laoghaire after an absence of 35 years. Many craftsmen have been involved in this - most notably Steve Morris and his team at Kilrush Boatyard - but none of it would have happened without the undying belief of Fionan de Barra in the value of the project and its meaning for Dun Laoghaire and its maritime community, combined with the inspired support of Hal Sisk in fulfilling a vision which is a great service to sailing not only in Dublin Bay, but nationally and internationally as well.

The restored DB21 Garavogue (built James Kelly of Portrush in 1903) sails north into Dalkey Sound on Friday July 30th 2021, 35 years after she'd last sailed through the Sound, bound for Arklow and an uncertain future. Photo courtesy DB21 Assoc.

The restored DB21 Garavogue (built James Kelly of Portrush in 1903) sails north into Dalkey Sound on Friday July 30th 2021, 35 years after she'd last sailed through the Sound, bound for Arklow and an uncertain future. Photo courtesy DB21 Assoc.

The latest in the Royal Irish Yacht Club’s ‘Home Together’ series of online talks will see Hal Sisk recount a brilliant season with Peggy Bawn in classic events across the Atlantic from Maine to New York.

Many members are familiar with images and tales of classic regattas in the Med, but New England is a different prospect.

Hal will describe a very special campaign in the classic regattas of New England in his historic cutter Peggy Bawn and the cruising in between such venues as Newport, Camden, Castine and Stonington.

The illustrated adventure will also include a professionally made short film of Clare Francis racing Peggy Bawn in Cowes in 2018. Clare was the first woman to race singlehanded across the Atlantic in 1973 and skippered a Swan 65 in the Round the World race in 1977.

Be sure to tune in from 7.30pm tomorrow evening, Wednesday 6 May. RIYC members should have their invite emails but contact the Club Secretary if there are any issues.

Upcoming talks include acclaimed yacht designer Ron Holland (13 May), Bobby Kerr on climbing Point Burnaby in the Alps (15 May) and Prof Andrew Curtain on cruising Scandivanva (20 May).

Kilrush on the Shannon Estuary Shows the Way for Dun Laoghaire – Again

In 1828, when the recently re-named and still only semi-finished harbour of Kingstown on Dublin Bay staged its first regatta, it certainly gave an indication of the transformed place’s potential for waterborne sport. Yet it was not until 1831 that the first club – the Royal Irish YC in its earliest form – came into being. But on the south coast at Cork, the stately Water Club had been going about its manoeuvres since 1720, and was organising racing by 1765 and probably earlier while going on to become the Royal Cork YC in 1831. And on the west coast in Kerry and along the Shannon Estuary, recreational sailing was relatively well established – not least because it provided a useful cover for some profitable smuggling of low-volume high-value commodities from France, Spain and Portugal.

Be that as it may, by the 1820s regattas were being staged at what was then one of the main ports, the sheltered though tidal Shannonside creek at Kilrush on the south coast of Clare, and in 1828 Maurice “Hunting Cap” O’Connell – the uncle and effectively guardian in his youth of Daniel O’Connell of Derrynane, The Liberator - organised a Kilrush regatta which led to the formation of the Royal Western Yacht Club of Ireland.

The club thrived, and by 1838 it was the named club of at least two dozen yachts, some of them quite substantial, with 18 of them based in Kilrush while others were kept by their owners on moorings in the estuary beside their often quite stately homes, a classic case being the Knight of Glin with his 30-ton cutter Rinevella moored off Glin Castle on the south shore.

The Shannon Estuary – 55 nautical miles of history-filled waterway

The Shannon Estuary – 55 nautical miles of history-filled waterway

Thus the sailing scene on the Atlantic seaboard was thriving while the Dublin Bay programme was still in its infancy. But the situation was totally and tragically changed with the Great Famine of 1845-47. Apart from the human scale of the disaster - which we still do not fully grasp, and probably never will – while it may be simplistic to say that the economy of Western Ireland was destroyed, basically that’s what happened. Despite this, much of life along the east coast went on as normal, and yachting in Kingstown underwent a phase of rapid development.

Retreating from the wasteland which the West had become, what was left of the Royal Western Yacht Club of Ireland became an itinerant organisation, based for a while in Dublin city and then in Dun Laoghaire and finally in Cork Harbour, where it was supposedly wound up in Cobh in 1870. But it so happened that back in Kilrush the Glynn family had retained some artefacts, documents and records of the old club, other memorabilia was gradually traced and brought home over the years, for there were those who felt that the old Royal Western YC of Ireland had never really died, it was only sleeping, and all it needed was some miraculous revival of the port of Kilrush to waken it up.

Kilrush did slowly revive as a port after the famine, but it was for the utilitarian purposes of handling cargo in the dock, while a pier nearby at Cappagh served the needs of the Shannon ferry steamers which were such a feature of the estuary before rail and then road took over. After that, the port became a ghost of its former self, but there were those who could see its potential.

And the miracle came in 1990, when Brendan Travers of Shannon Development spearheaded the project to provide a barrier with a sea lock to make Kilrush into a proper marina. Today, it has facilities which put the allegedly pace-setting East Coast ports to shame, with the marina run by Simon McGibney while master-shipwright Steve Morris (who’s from New Zealand, but Irish women like his wife Michelle have a way of ensnaring useful talent and keeping it here) has been with the boatyard with its commodious sheds and workshops since 2001, where they seem capable of all forms of boat-work in any material, and to world class standards too.

Kilrush today, with the extensive boatyard (centre) providing facilities that most other Irish sailing harbours can only dream of

Kilrush today, with the extensive boatyard (centre) providing facilities that most other Irish sailing harbours can only dream of

With this setup developing, the Royal Western Yacht Club of Ireland re-emerged as the club at Kilrush with a healthy marina-based fleet. In the early summer of 2007, a bundle of energy from Limerick called Ger O’Rourke contacted the Royal Ocean Racing Club to enter his Cookson 50 Chieftain for the up-coming Rolex Fastnet race in August. He was told he’d be 46th on the waiting list, but not to worry - many early entries tended to drop out, and with bad weather forecast, he was in with a good chance of a place.

O’Rourke had just completed a Transatlantic race from Newport to Hamburg to take second place, but he had this weird superstition of never entering his boat for the next big race until the previous one had been completed. Once again it came good - on the Tuesday before the Fastnet was due to start on the Saturday, the RORC told him it was all systems go, the place was there, so he rushed his crew together, they sailed a magnificent heavy weather race, and Chieftain became the overall winner of the 2007 Rolex Fastnet Race, making the Royal Western of Ireland and Kilrush the only Irish club and port which can claim this rare distinction.

Ger O’Rourke’s Cookson 50 Chieftain from Kilrush shortly after the start of the Rolex Fastnet Race 2007, which she won overall – the first and still the only Irish boat to do so. Photo: Rolex

Ger O’Rourke’s Cookson 50 Chieftain from Kilrush shortly after the start of the Rolex Fastnet Race 2007, which she won overall – the first and still the only Irish boat to do so. Photo: Rolex

All of which is a roundabout way of saying that when the most varied group of people in Irish sailing that you’ve ever seen converged on Kilrush in Tuesday’s incredibly bright and uninterrupted sunshine for the launching of the first of the re-born Dublin Bay 21s which are being brought back to life for Hal Sisk and Fionan de Barra by Steve Morris and the equally talented Dan Mill and their team (which includes Kilrush’s own James Madigan of Ilen fame), we weren’t making a patronizing visit to encourage a new place on its way.

The Naneen Restoration Team included (left to right) Steve Morris, James Madigan, Hal Sisk, Fionan de Barrra, Fintan Ryan and Dan Mill. Photo: W M Nixon

The Naneen Restoration Team included (left to right) Steve Morris, James Madigan, Hal Sisk, Fionan de Barrra, Fintan Ryan and Dan Mill. Photo: W M Nixon

On the contrary, it was more like a pilgrimage to a special place that was outdone in historic sailing style only by Cork Harbour, for in Dublin Bay organised sailing was just getting going when Kilrush was thriving, and Belfast Lough was likewise barely started. But back in the 1820s when life lacked many of today’s mostly superfluous distractions, sailing was big in the west – think Sligo too - and Kilrush and the Shannon Estuary were in the forefront of its energetic development, typified by the Knight of Glin who took his cutter Rinevella to Galway in 1834 for a big regatta, and won western sailing’s equivalent of the Galway Plate.

However, from 1850 onwards there’s no doubting Dublin Bay was a global pace-setter in sailing development, and the establishment of Dublin Bay Sailing Club in 1884 provided an organisation which very quickly was co-ordinating all the sailing of the three major Kingstown yacht clubs, establishing new classes of increasing boat sizes such that by 1898 it was the DBSC’s imprimatur which brought the famous Fife-designed Dublin Bay 25ft ODs into being.

All these numbers refer to the waterline length, which means the 25s were generously-canvassed 37-footers, the jet-set of Dublin Bay One-Design racing. So much so, in fact, that very soon there was a growing movement for something similar in style but in a smaller and more economically-manageable size. William Fife was busy with America’s Cup yachts for Thomas Lipton and other large projects for super-rich clients, so they turned to Scotland’s new rising star in the yacht design firmament, Alfred Mylne, who had already created a useful 20ft waterline design for Belfast Lough sailors, the Star class, which set a simple gunter sloop rig.

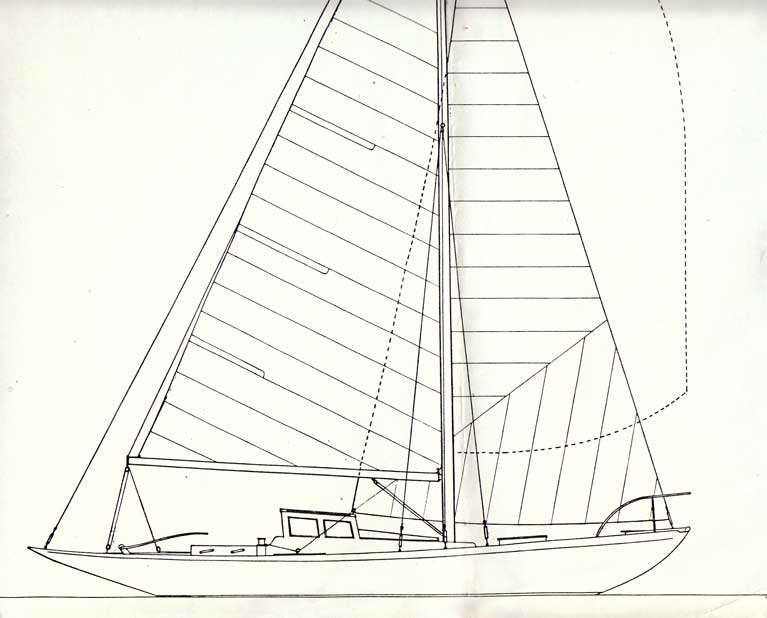

Simplicity was not the keynote in the original rig of the new Dublin Bay 21s in 1903 – in fact, for the first 60 years of their existence, they were defined by this challenging jackyard topsail-setting gaff cutter rig.

Simplicity was not the keynote in the original rig of the new Dublin Bay 21s in 1903 – in fact, for the first 60 years of their existence, they were defined by this challenging jackyard topsail-setting gaff cutter rig.

But simplicity was not the keynote for the new Dublin Bay 21. Slightly larger, she had a longer and more elegant stem than the Star’s rather snubbed bow, and instead of a straightforward hyper-economical gunter mainsail with just one headsail, she set acres of gaff rig with a jackyard topsail and was cutter-rigged with it – four sails by comparison with the Star’s two, and that’s before you add the spinnaker.

The first three boats were building with Hollwey of Ringsend in the winter of 1902-03, as the established Kingstown builders James Clancy and J E Doyle were busy with other works, notably yet more DB 25s. The bigger class had received a shot in the arm with a new boat ordered for the 1903 season for the Viceroy, Lord Dudley, to be built by Doyle. This meant that when the first five DB 21s raced in 1903 (two more having been built by James Kelly of Portrush), their advent was somewhat overshadowed by all the razzmatazz attached to the Viceroy racing in his new DB25 Fodhla.

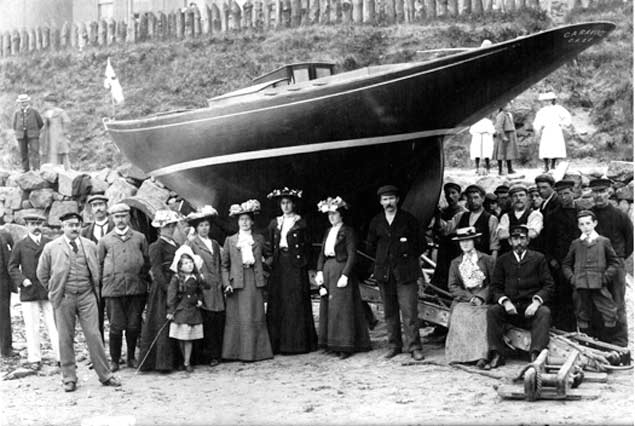

Garavogue on her launching day at Portrush in 1903

Garavogue on her launching day at Portrush in 1903 Garavogue in action in Dun Laoghaire Harbour. Her replacement hull has been built by The Elephant Boatyard in England, and is now in Kilrush for completion

Garavogue in action in Dun Laoghaire Harbour. Her replacement hull has been built by The Elephant Boatyard in England, and is now in Kilrush for completion

But the smaller class’s quality was soon recognized, and by 1908 they’d achieved their optimum number of The Sacred Seven with Geraldine being built by Hollwey, while Naneen – no 6 – had emerged as the only Kingstown-built boat. She was the work of James Clancy in 1905, built for a serial racing yacht owner called T Cosby Burrowes from Cavan. He must have owned a substantial part of that most rural of Irish counties, for it was presumably rental income which enabled him to be a member of eleven yacht clubs in Ireland, Scotland and England while buying new boats on a fairly regular basis. But though he raced in many places, Dublin Bay was his spiritual sailing home, and he’d served as DBSC Vice Commodore in 1900-1901.

The Ireland of people like Cosby Burrowes was to change inexorably through the 20th Century, yet the Dublin Bay 21s steadily continued to give great sport with such consistency that, despite being just seven in number, the regularity of their turnouts and the spectacular nature of their appearance became the best-known feature of Dublin Bay sailing.

But by the early 1960s the advent of series-production built fibreglass boats with alloy masts and synthetic sails was making their continued existence problematic, and in 1963 they persuaded veteran designer John Kearney (he was 83 at the time) to provide them with a new masthead Bermudan rig of 400 square feet as opposed to the original gaff’s 600, and they also requested a new coachroof with a doghouse to provide standing headroom.

The new masthead Bermudan rig as fitted in 1963 enabled exceptional loading to be applied by the standing backstay, while the unsightly new doghouse distracted attention from the elegance of the sheerline.

The new masthead Bermudan rig as fitted in 1963 enabled exceptional loading to be applied by the standing backstay, while the unsightly new doghouse distracted attention from the elegance of the sheerline.

John Kearney was up to his tonsils at the time designing and over-seeing the building of the 54ft yawl Helen of Howth for Perry Greer, but his age of 83 notwithstanding, he took on this extra task and the simple rig he created balanced very well. It gave good performance while needing a smaller crew, but veterans of that Dublin Bay 21 era who were in Kilrush on Tuesday were mixed in their approval.

Paddy Boyd raced on his father’s Oola as a schoolkid, and he could well remember the magic moment when the vital but inadequate bilge pump – his special job - was replaced by a luxurious new Whale Gusher 25. Anyway, he is in no doubt that the new rig gave the class a further 22 years of useful life. But Fionan de Barra, the Keeper of the Flame who has kept The Sacred Seven intact as a group ever since they stopped sailing, and his project partner Hal Sisk, are of the opinion that the new masthead rig with its standing backstay – often tensioned with a wheel - meant that the mast was being pushed down into the hull in a destructive way that hadn’t been possible with the original gaff rig with its running backstays.

DB21 veteran Paddy Boyd with Naneen in Kilrush. Racing regularly as a schoolboy aboard the family’s Oola, his happiest memory is of the day his father finally acquired a bilge pump which was man enough for the job. Photo: W M Nixon

DB21 veteran Paddy Boyd with Naneen in Kilrush. Racing regularly as a schoolboy aboard the family’s Oola, his happiest memory is of the day his father finally acquired a bilge pump which was man enough for the job. Photo: W M Nixon

Either way, the class was getting very tired by the mid-1980s. But any considered decision as to their future was decided by Hurricane Charlie in August 1986, with northeast gales of unbelievable ferocity sweeping into Dun Laoghaire to leave the Dublin Bay 21s either sunk or seriously damaged.

That was 1986. It is now 2019. But the sheer style of the DB 21s has never been forgotten. And as for what was left of the boats themselves, Fionan de Barra and friends managed to keep them intact as a group in various locations in County Wicklow, while one proposal after another was put forward for their revival.

Naneen, the only DB21 to have actually been built in Dun Laoghaire, looking very sad in a Wicklow farmyard some years after the class had stopped sailing in 1986. Photo: Afloat.ie/David O’Brien

Naneen, the only DB21 to have actually been built in Dun Laoghaire, looking very sad in a Wicklow farmyard some years after the class had stopped sailing in 1986. Photo: Afloat.ie/David O’Brien

Naturally the yachting historian and classic yacht activist Hal Sisk was interested, but he had other projects in hand such as the restoration of the 1894 G L Watson 37ft cutter Peggy Bawn, a meticulous project finished in 2003 which has seen Peggy Bawn winning regattas and awards on both sides of the Atlantic.

But gradually he and Fionan started putting ideas together, and in a world which changes more rapidly than ever, they reckoned that a way of restoring the DB 21s as a class is to think of new ways of ownership and use. To do this they would have to use a rig simpler than the labour-intensive time-consuming jackyard tops’l setup of the originals, and a straightforward gunter sloop set up such as Alfred Mylne designed for a Scottish-built boat to the hull design – Zanettta in 1918 - seemed to fit the bill.

The easily-handled rig designed by Alfred Mylne for the Scottish-owned Zanetta of 1918 is the basic inspiration for the new rig on the class in Dublin Bay

The easily-handled rig designed by Alfred Mylne for the Scottish-owned Zanetta of 1918 is the basic inspiration for the new rig on the class in Dublin Bay

A traditional and historic local class such as the Howth 17s is one in which the people involved and their sense of community through the boat are every bit as important as the new boat itself, and thus the numbers of interested people are maintained over the years. But where a class has been sitting together but derelict and moth-balled for thirty years with the original owners and crews dying off and all ownership rights gradually accruing to one person – in this case Fionan de Barra – much radical thinking is needed.

Howth Seventeens in action in their time-honoured style. They have been functioning continuously as a racing class since 1898, and with 19 boats, have an established total crewing panel of around a hundred people for whom a Seventeen is the first choice if they wish to go sailing. But as the new-look Dublin Bay 21s will be starting from scratch with no basic crewing panel, a completely new approach to ownership and the running of the boats is being devised. Photo Stormyphotos/Tom Ryan

Howth Seventeens in action in their time-honoured style. They have been functioning continuously as a racing class since 1898, and with 19 boats, have an established total crewing panel of around a hundred people for whom a Seventeen is the first choice if they wish to go sailing. But as the new-look Dublin Bay 21s will be starting from scratch with no basic crewing panel, a completely new approach to ownership and the running of the boats is being devised. Photo Stormyphotos/Tom Ryan

Thus Hal and Fionan have come up with the idea that the restored Dublin Bay 21 class – with the hulls built-in modern wood-style using the WEST system – would be an association-owned class of boats in a Dun Laoghaire Harbour which is itself being re-imagined for its use as an amenity and recreational area. To this new-use classic harbour they would bring a group of classic boats which are maintained as a unit, and accessible to all for sailing and special racing events based on the harbour of which they were such a natural part for 83 years.

The “new” Naneen at an early stage of her re-build. Photo: Steve Morris

The “new” Naneen at an early stage of her re-build. Photo: Steve Morris

It’s an ambitious idea, but in this age of disappearing private ownership and shared use of vehicles ashore, with new business names like Borrow-a-Boat coming to the fore, it could well be that this re-born 116-year-old class is in the vanguard of how we will sail in the future.

Meanwhile, the boats have had to be re-built, and in Ireland they started with the only Dun Laoghaire-built boat, the Naneen of 1905 built by James Clancy, and took her to Steve Morris in Kilrush, while the Garavogue – built by James Kelly of Portrush in 1903 – went to classic boat specialists The Elephant Boatyard in the south of England.

Even with such skill involved in both England and Ireland, it has been a demanding task, but fortunately beforehand they could draw on the knowledge of design historian and classic specialist Theo Rye, and then after his sad and untimely death in 2016, the many talents of Paul Spooner took on the advisory role, and gradually the developing project began to take shape.

The casually interested might think it is all taking a remarkably long time, but so many novel concepts and new ways of thinking about boat use are evolving as each stage is passed that when the “new” DB21 class is complete, we’ll find that Hal Sisk and Fionan de Barra are true pioneers of sailing.

A meeting of minds. Ilen skipper Paddy Barry (right) with Frank Larkin (left) and Steve Morris as the about-to-be-launched Naneen flies the DBSC burgee. Photo: W M Nixon

A meeting of minds. Ilen skipper Paddy Barry (right) with Frank Larkin (left) and Steve Morris as the about-to-be-launched Naneen flies the DBSC burgee. Photo: W M Nixon

Certainly the very supportive crowd which turned up in the Kilrush sunshine on Tuesday to wish them and the build team of Steve Morris and Dan Mill was representative of a very wide swathe of people seriously interested in classic boats and what you can do with them, such as Paddy Barry and Jarlath Cunnane fresh back from the restored Ilen’s voyage to Greenland, and James Madigan who was not only closely involved in re-building the Ilen in Limerick and Oldcourt and sailing to Greenland, but is from Kilrush and is now back home working with Steve and Dan on completing the Garavogue, whose hull has arrived in Kilrush from England.

There were several there who had sailed on the DB21s in the old days, in fact your columnist sailed in the Geraldine when she was still gaff-rigged in the ownership of Paul Johnson. But much more interesting were the views of Paddy Boyd, who has distant childhood memories of the old rig, and happy recollections of youthful exuberance under the new one.

In gazing at Naneen as she glowed in the sunshine with a sense of weightlessness in the boat hoist, he was moved to comment on how elegant the sheerline now looked under the original coachroof. John Kearney himself preferred neat low coachroofs - he thought doghouses were the invention of the devil - but the DB 21 owners of 1963 demanded it, and the result was a boxy shape which somehow disguised the fact that the original sheerline was well nigh perfect.

Certainly it was well-appreciated by Ian Malcolm of Howth, who was there on behalf of the Howth 17s but with a special interest, for after Storm Emma wreaked havoc on the Howth Seventeen fleet in their pier-end storage shed in March 2018, it was boat no 6, Anita built by James Clancy in 1900, which was the only total loss. Thus it fell to Ian, with his French connections, to arrange her re-build by Paul Roberts’ Les Atelier d’Enfer organisation in Douarnenez under the French government’s subsidized boat-building schools programme.

People who re-build James Clancy boats with James Clancy people are left to right) Ian Malcolm who arranged the French re-build of Howth 17 No 6 Anita, built by James Clancy in 1900, with Ann Clancy Griffin, James Clancy’s grand-daughter who lives in Kilrush, James Clancy’s great-grand-daughter Sinead Griffin (also of Kilrush), and Hal Sisk, who has been central to the re-build of Naneen, DB 21 No 6, built by James Clancy in 1905. Photo: W M Nixon

People who re-build James Clancy boats with James Clancy people are left to right) Ian Malcolm who arranged the French re-build of Howth 17 No 6 Anita, built by James Clancy in 1900, with Ann Clancy Griffin, James Clancy’s grand-daughter who lives in Kilrush, James Clancy’s great-grand-daughter Sinead Griffin (also of Kilrush), and Hal Sisk, who has been central to the re-build of Naneen, DB 21 No 6, built by James Clancy in 1905. Photo: W M Nixon

This meant that in Kilrush on Tuesday we’d two sets of people who have been closely involved in the re-building of a Clancy of Dun Laoghaire boat during the past two years, but the coincidences didn’t stop there, as James Clancy married a Kilrush woman, and the family now has many connection in the town, with his grand-daughter Ann Clancy Griffin with her daughter Sinead Griffin doing the launching honours after Father Anthony Keane – who was Brother Anthony Keane of Glenstal Abbey before he went up to Greenland on Ilen – had made a quietly elegant ceremony out of blessing the boat.

When he sailed to Greenland in the Ilen in July, he was Brother Anthony of Glenstal Abbey, but now he is Father Anthony Keane, and in his new capacity, he blessed Naneen before her launching on Tuesday. Photo: W M Nixon

When he sailed to Greenland in the Ilen in July, he was Brother Anthony of Glenstal Abbey, but now he is Father Anthony Keane, and in his new capacity, he blessed Naneen before her launching on Tuesday. Photo: W M Nixon

And then Naneen was launched. Simply by watching her being lowered gently we were given ample opportunity to admire the way in which Alfred Myne has harmonised the lines, such that every sweet curve complements all the other, with the little cabin, in particular, being a masterpiece. On the original drawings Mylne light-heartedly named its interior as “The Den”, but the 21s proved such good seaboats that one of the original owners, Herbert Wright who later went on to be founding Commodore of the Irish Cruising Club in 1929, took his new DB21 Estelle to Scotland on a cruise which worked out so well he wrote it up for Yachting Monthly magazine, which prompted Hal Sisk to claim that the Dublin Bay 21s were thus the world’s first genuine cruiser-racer class.

The harmony of Naneen’s pure lines as drawn by Alfred Mylne became even more evident as she was lowered gently into Kilrush Creek. Photo: W M Nixon

The harmony of Naneen’s pure lines as drawn by Alfred Mylne became even more evident as she was lowered gently into Kilrush Creek. Photo: W M Nixon

Is she not very lovely? That Alfred Mylne, he certainly had an eye for a boat….. Photo: W M Nixon

Is she not very lovely? That Alfred Mylne, he certainly had an eye for a boat….. Photo: W M Nixon

Clearly there’s a quality to their size and the way they feel when you step aboard which seems just right, and suggests uses more ambitious than simply racing in Dublin Bay, though heaven knows the pace of their racing was scarcely simple, for it was hectic and furiously – sometimes genuinely furiously – competitive.

But all would be well at the end of the day, and with the new creation afloat, Fionan ushered us back to the boat-building shed for the perfect boat-launching lunch, a simple yet effective and nourishing boat-oriented meal provided by Noel Ryan of Ryan’s Butchers & Deli in the town. It was an extension of the opportunity to meet the huge diversity of people who had come to wish this extraordinary project well, a glimpse of the area’s diversity for there was time to talk with Frank Larkin of Limerick, whom I first met through sailing. Then when he became Corporate Communications Manager for Shannon Development, he used to recruit me to give slide shows to Limerick’s sailing fraternity, and the next day we’d go to Foynes or Kilrush to see the developing local setup, all extremely educational for this was in the days before Kilrush had its barrier and Foynes had yet to have its largely voluntarily-installed marina.

The perfect post-launch boatyard lunch gets underway beside a new traditional gleoiteog which is another high-standard project the yard has underway at the moment. Photo: W M Nixon

The perfect post-launch boatyard lunch gets underway beside a new traditional gleoiteog which is another high-standard project the yard has underway at the moment. Photo: W M Nixon

There too was Kim Roberts who has run a boatyard in her time, and then driven an enormous crane for big contracts on the south shore, and has since been manager of Kilrush marina but is now running Vandeleur antiques from The Old Forge in Killimer and sailing a restored classic timber Drascombe which, as we saw last week, she has taken about as far up the Shannon as it is possible to get from Kilrush.

From up the Shannon was David Beattie of Lough Ree, whose steel version of Slocum’s Spray may have originated in the Lough Ree area, but now under David’s command she has cruised extensively in the Med before returning recently to Ireland for work to be done at the Ryan & Roberts boatyard at Askeaton on the Shannon Estuary’s south shore. And equally appreciative of the Naneen restoration was that legendary shipwright sailor Albert Foley, who’s on the mend after a recent illness, and plans to get his Swan 36 – which he re-built after everyone else considered her a write-off after she’d been run down by a survey vessel – back sailing again.

Then came the moment of truth - the post-lunch revisit to the floating Naneen to see how things were. The sheer pleasure of being aboard a pristine wooden boat in the sunshine with new varnishwork and a slight hint of linseed oil and all the aromas of a healthy environment in The Den were followed by that important ceremony: The First Lifting of the Floorboards.

Super workmanship in evidence below on Naneen, looking forward from “The Den”. Photo: W M Nixon

Super workmanship in evidence below on Naneen, looking forward from “The Den”. Photo: W M Nixon

They’ll have a problem with Naneen. No arachnophobes will be able to sail aboard. The bilges fore and aft were bone dry. Inevitably some dust and other peculiar forms of nutrition and the occasional tiny insect will find their way in, and in time there will be a spider’s web or two. Definitely not a boat for arachnophobes……

Exquisite workmanship hiding structural strength – the hanging knee fitted in Naneen to distribute the load from the internally-installed main shroud chainplate. Photo: W M Nixon

Exquisite workmanship hiding structural strength – the hanging knee fitted in Naneen to distribute the load from the internally-installed main shroud chainplate. Photo: W M Nixon

Before leaving Kilrush for the long haul home courtesy of Ian Malcolm with his high-and-very-mighty boat-towing vehicle, we had one further pleasant task – to pay our respects to Sally O’Keeffe in the marina. She is the handsome workmanlike 25ft cutter designed by the talented Myles Stapleton to a concept based on the Shannon Estuary hookers of all sizes which used to carry cargoes the length and breadth of the mighty waterway, and there was one in particular called Sally O’Keeffe which was based in Querrin to the west of Kilrush, where she’s part of folk memory.

A sort of Men’s Shed group in Querrin got together to build an interpretation of the Sally in the big barn at a local farm, Steve Morris came along and kept the work on track, and the result is one of the most attractive boats in all Ireland, a no-nonsense multi-purpose craft which has turned heads and won competitions at places as far apart as Glandore, the Baltimore Woodenboat Festival in West Cork, and Cruinniu na mBad in Kinvara on Galway Bay, making a point of sailing to these places along the Atlantic seaboard from Kilrush.

Sally O’Keeffe is the outcome of a very successful community venture in neighbourhood boat-building guided by Steve Morris.

Sally O’Keeffe is the outcome of a very successful community venture in neighbourhood boat-building guided by Steve Morris. Steve Morris – he seems to be able to turn his hand to any boat-building project with complete success. Photo: W M Nixon

Steve Morris – he seems to be able to turn his hand to any boat-building project with complete success. Photo: W M Nixon

She’s about as perfect as you can get in her way, yet she’s as different as possible from the equally perfect Naneen, and we’d the chance to compare them directly, for even as we were admiring Sally, the Naneen came into the berth just across the walkway.

All I can say is that when some project gets the Steve Morris touch, it becomes something very special indeed. We departed on a high, determined to make the best of that extraordinary day by enveloping the entire Shannon Estuary experience through heading homewards by way of the Killimer-Tarbert Ferry, and along the south shore we were able to look across to the islands at the mouth of the estuary of the Fergus River where the 1886 America’s Cup Challenger Galatea came to visit Paradise House (that’s really what it was called), the Shannonside ancestral home of owner William Henn.

Then we swept into Foynes to admire the crisp style of the thriving yacht club while gazing thoughtfully across to the cottage on Foynes Island where global circumnavigation pioneer Conor O’Brien of Saoirse fame spent his last years, and where the restored Ilen had come in the Autumn of last year to pay her respects, and then we went to see Cyril Ryan and the wide range of work he does at Ryan & Roberts at Askeaton, where he has a boatyard in classic style where we marvelled at the huge road crane Kim Roberts used to drive, and marvelled equally at the enormous tidal range in the River Deel, for David Beattie’s Ree Spray was a very long way down indeed in a muddy pool at the pontoon.

Product line…..the “new” Naneen (beyond) and Sally O’Keeffe (foreground) get together in Kilrush Marina at the end of an extraordinary day. Photo: W M Nixon

Product line…..the “new” Naneen (beyond) and Sally O’Keeffe (foreground) get together in Kilrush Marina at the end of an extraordinary day. Photo: W M Nixon

And finally, we went for a pit stop in the Dunraven Arms in Adare and wondered again at the sometimes misunderstood genius of the neighbourhood’s Lord Dunraven, with his two America’s Cup Challenges in 1893 and 1895. Then with a seemingly eternal sunset at our backs, we left Ireland and went back across the isthmus to Howth, simply stunned by the memory of the incredible range of the Shannon Estuary’s sailing history and its many links, a memory which had somehow given us a much clearer understanding of what it is that Hal Sisk and Fionan de Barra are trying to achieve with their pioneering vision for the future of the DB21 class.

Naneen is coming home….Naneen, the only Dublin Bay 21 to be actually built in Dun Laoghaire, is the first one to be restored. She is seen here in the successful ownership of Terry Roche during the 1950s. Photo courtesy Olga Scully

Naneen is coming home….Naneen, the only Dublin Bay 21 to be actually built in Dun Laoghaire, is the first one to be restored. She is seen here in the successful ownership of Terry Roche during the 1950s. Photo courtesy Olga Scully

There is a Sport of Sailing & a Sport of Yacht Ownership

“For many people yacht ownership is enough. They buy a boat and they keep it in a marina and they don’t go sailing very often and they go there for picnics and so on, but for some people you can combine the two and you can get the best enjoyment from your boat, using it, which is the main thing.”

There is a sport of sailing and there is a sport of yacht ownership, glassfibre boats are a bit anodyne and Dublin has the classiest of boats sailing. Those are pretty strong views, but made by a man whose opinions command respect - the exponent of classic boats, yacht restoration and history, Hal Sisk, who I met as he was attending to his Water Wag, Good Hope, which he has been racing for 39 years and that he had brought to the West Cork harbour of Glandore for the Classic Boats Regatta. We discussed what is happening to yacht racing and concern that fleets have been falling off in numbers around the coast. “In 1887 Water Wags gave the world the first one-design boat and we still race them every week in Dublin Bay. When I started in the Class we had five or six racing. We had 27 last week on the water and more young people are joining the Class in which there is a great buzz. That shows what can be done in racing.”

We discussed glass fibre yachts which he considers a bit “anodyne” and doesn’t find them as interesting as the wooden classics. He pointed to the “National 18 wooden clinker boats, a fine boat,” but mostly gone from the racing scene. He contrasted this with older wooden boats still actively racing in Dublin, pointing to the Water Wages, the Howth 17s and the Glen 21s.

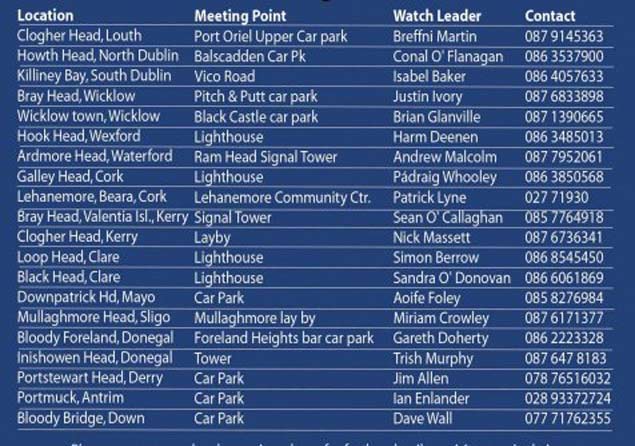

Hal Sisk has boundless enthusiasm for the sport which comes across in my interview with him which you can hear on this week’s Podcast. Also on the PODCAST, this Saturday is Whale Watch Day. The Irish Whale and Dolphin Group has recorded a thousand sightings of whales and dolphins this Summer, but there are fears that ‘killer whales’ could be threatened with extinction in Europe. Whale Watching locations and details are here:

LISTEN to the PODCAST:

Tom MacSweeney presents THIS ISLAND NATION programme on radio stations around Ireland

Historic Belfast Lough Boatyard Lives On Through Classic Yachts

The recreational marine industry is a demanding trade. Your customers buy boats for pleasure, so they assume it’s a fun business to work in. Thus there’s no lack of potential boat designers and builders to be found among the children of those who only sail for sport and fun, for they see that the adults enjoy being around boats, and they get to think that being around boats all the time for work and play is the only way to live.

But in the end, business is business. The bottom line rules everything else. However enthusiastic young people may have been when first going into the boat trade, as they battle on with running their own marine business they find the world of commerce can become a cruel place. W M Nixon considers the challenges of boat-building, and looks at the story of John Hilditch of Carrickfergus, who was one of the brightest stars of the Irish boat-building industry in the golden age of yachting, yet his light was extinguished after barely two decades.

The name of Hilditch of Carrickfergus is synonymous with classic yachts of significant age. John Hilditch built the 36ft G L Watson-designed cutter Peggy Bawn in 1894, and she still sails. In fact, she sails in better shape than ever, as she had a meticulous restoration completed for Hal Sisk of Dun Laoghaire in 2005.

More recently, in 2013 the Hilditch-built Mylne-designed Belfast Lough Island Class 39ft yawl Trasnagh was restored for Ian Terblanche in Devon in time for her Centenary. And in 2015, the Belfast Lough OD Class I Tern – 37.5ft LOA to a William Fife design and built in 1897 with seven sister-ships by John Hilditch - has appeared in Mallorca so superbly restored that when she went on to Les Voiles de St Tropez at the end of September, she won her class despite it being heavy weather, and she only just out of the box.

Peggy Bawn in her first season afloat in 1894. She was built for A J A Lepper, Commodore of Carrickfergus Sailing Club, who was one of John Hilditch’s most loyal clients. Photo courtesy RUYC

Peggy Bawn in her first season afloat in 1894. She was built for A J A Lepper, Commodore of Carrickfergus Sailing Club, who was one of John Hilditch’s most loyal clients. Photo courtesy RUYC

A monumental achievement. All the boats of the new Fife-designed Belfast Lough OD Class 1 of 1897 were built by John Hilditch in less than a year. Photo: Courtesy RUYC

But we don’t have to go to distant restoration specialists to find evidence of the large and varied Hilditch output. The first five boats of the Howth 17 OD class were built by John Hilditch immediately after he’d built the eight Belfast Lough Class I boats. The little new Howth gaff sloops – rigged with huge jackyard topsails as they still are today - sailed the 90 miles home down the Irish Sea to Howth in April 1898, and had their first race on May 4th 1898. All five of the original Hilditch creations continue to race with the thriving Howth 17 class, which today has eighteen boats.

The Howth 17s Aura (left) and Pauline. Aura is one of the original five Howth 17s built for 1898 by John Hilditch immediately after he had completed the Belfast Lough Class I boats. Photo: John Deane

This concentration of yacht design development in a short time span, and through just one boatyard, is rare but not unique – the great name of Charlie Sibbick of Cowes shone equally briefly but even more brightly at much the same time, as he was a designer too. But Sibbick made his name in an established international centre for sailing. Yet when John Hilditch – who was both a seafarer and a fully-qualified shipwright – established his yard at Carrickfergus on Belfast Lough in the winter of 1892-93, the north of Ireland was still a relative backwater in international sailing terms. Thus his achievement is indeed remarkable. For by the time Hilditch closed down in the winter of 1913-14, he had put Belfast Lough firmly in the global picture as a pace-setter in yacht development, and his pivotal role in that transformation is gaining increasing recognition.

Not that there hadn’t been sailing in Belfast Lough before Hilditch came along. There are many yacht and sailing clubs around this fine stretch of sailing water, and the most senior of them is Holywood Yacht Club (on the waterfront below the hills where Rory McIlroy learned to pay golf), which dates back to 1862. And in 1866, two more new clubs came into being – Carrickfergus Sailing Club which was obviously location-specific, and the Ulster Yacht Cub, which became the Royal Ulster Yacht Club in 1869, but was a premises-free moveable feast until 1898, when America’s Cup challenger Thomas Lipton insisted it have a clubhouse, which was duly opened on an eminence close above the Bangor waterfront in April 1899.

The shared foundation year which goes back through the mists of time to 1866 means that both clubs will be celebrating their 150th Anniversaries in 2016. They’ve been quietly working on their separate plans towards celebrating this significant date, with a massive new history of the RUYC under way for a couple of years now and due for publication in the Spring, while Carrickfergus also has plans in the publication line.

Yet although there is much to write about now, in both club’s cases the pace of development was relatively slow until the late 1880s, for until that time, the business of the rapidly expanding city of Belfast was business, and more business. It wasn’t until the 1880s that leisure sailing began to get serious attention from the rapidly growing middle classes of the greater Belfast area. But once they did begin to take it up, they did so with complete enthusiasm, and the sailing pace of Belfast Lough during the 1890s, and on towards 1910, had few rivals.

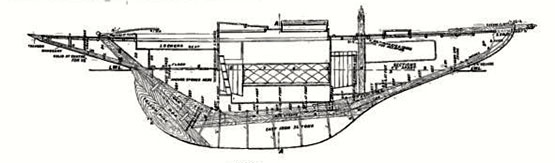

For the rapid yacht design development seen during John Hilditch’s busy years, compare this with the next image. The old-style hull of Peggy Bawn is revealed as she is lifted out of the Coal Harbour Yard in Dun Laoghaire in 1996 for a first attempt at restoration. Later, Hal Sisk took over the project, and it was completed for him by Michael Kennedy of Dunmore East. Photo:W M Nixon

The new style shape. Although they were built only three years after Peggy Bawn, the Fife-designed Belfast Lough Class I boats had a much more modern hull shape and were primarily racing boats, yet they were required to be well capable of sailing to Scotland and Dublin Bay, and did so

The new style shape. Although they were built only three years after Peggy Bawn, the Fife-designed Belfast Lough Class I boats had a much more modern hull shape and were primarily racing boats, yet they were required to be well capable of sailing to Scotland and Dublin Bay, and did so

Formidable performers. The Belfast Lough Class I boats Merle (6, Brice Smyth) and Flamingo (2, John Pirrie) racing hard in 1898. Both owner-skippers were members of Carrickfergus SC, and based their boats there. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

Formidable performers. The Belfast Lough Class I boats Merle (6, Brice Smyth) and Flamingo (2, John Pirrie) racing hard in 1898. Both owner-skippers were members of Carrickfergus SC, and based their boats there. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

In order to meet this demand, John Hilditch was able to expand his new boatyard at an extraordinary pace. Even then, he couldn’t keep up with demand, such that one new Belfast Lough class, the Linton Hope-designed lifting-keel 17ft LWL Jewel Class of 1898, had to be built in Chester in England. And at the same time, the fishing-boat builder James Kelly of Portrush on the North Coast found that yacht-building to supply the new craze was much more lucrative than producing his own variant of the classic Greencastle yawl for fishermen on both the Irish and Scottish coasts, and he went into yacht-building both for Belfast Lough and Dublin Bay.

But in terms of overall contribution to the transformation of Belfast Lough sailing, John Hilditch was very much in a league of his own. So much so, in fact, that noted international classic sailing polymath Iain McAllister got to thinking last winter that even though no trace whatsoever now remains of this once famous yard, it was time and more for John Hilditch’s work to be celebrated, and how better than a Hilditch Regatta during 2016 to tie in with other Belfast Lough sailing celebrations?

It’s a great idea which seemed almost too good to be true. But thanks to quiet work behind the scenes, most notably by Wendy Grant who recently became Commodore of Carrickfergus Sailing Club neatly in time to hold the top post during the 150th celebrations (she’s the mother of renowned offshore navigator Ian Moore), plus a special sub-committee in RUYC which likewise holds to the notion that the early stages of good work are best done by stealth, a programme is emerging which will keep all organising parties happy while providing participants with a manageable user-friendly schedule.

It has all become viable during this past week thanks to the confirmation that the more distantly-located significant classic boats of the Hilditch oeuvre – Peggy Bawn of 1894, Tern of the 1897 Belfast Lough Class I, the Howth 17s of 1898, and Trasnagh, the Island Class yawl of 1913 – all hope to be in Belfast Lough towards the end of June 2016, where numbers will be further swollen by the Hilditch-built Royal North of Ireland YC Fairy Class of 1902, together with some of their sister-ships from Lough Erne.

The Hilditch-built Tern in a breeze of wind on Belfast Lough, 1898

Tern in a breeze of wind at St Tropez, September 2015.

In addition, the fleet will be increased by other classics of every type, coming together to wish the Hilditch boats well at this special time. And there’ll be a goodly contingent of Irish Sea Old Gaffers which will be heading towards the big event on Belfast Lough in late June by way of the Old Gaffers Rally at Portaferry in the entrance to Strangford Lough from June 17th to 19th.

But before getting carried away by anticipation of all this festivity, let us remember that this week’s thoughts were introduced by a precautionary reminder that the boat-building trade is no bed of roses. So just what did go wrong, that the much-admired Hilditch yard faced closure before the end of 1913, with the man himself dead – perhaps broken-hearted – before the end of 1914?

There seem to be a number of explanations, all of which combine to explain the sudden demise of a great enterprise. The incredible rate of economic expansion in Belfast – which had been accelerating virtually every year since around 1850 – seems to have first shown significant signs of slackening in 1910. The greater Belfast economy did continue to expand in the broadest sense, but the rate of expansion was now slowing.

During the rapid growth years, John Hilditch was able to meet demand, but regardless of the underlying economic patterns, by 1910 his market was beginning to reach saturation levels. If people had continued to change their boats every three years or so – as they’d anticipated doing when the Belfast Lough One Design Association was established in 1896 – then an artificial demand might have been maintained. But people were beginning to realise that a good one design boat was good for much longer than a mere three years. In fact, some argued that a class was only bedded in after three years. So the number of new boats being ordered dried to a trickle.

Yet those boats that were being ordered became individually larger. When the Alfred Mylne-designed 39ft Belfast Lough Island Class yawls began to be conceptualised as the world’s first true cruiser-racer one designs in 1910, they would be far and away the biggest and most expensive one designs Hilditch had yet built. He held out for a price of £350 per boat, but the potential owners – hard-headed Belfast businessmen determined to drive a tough bargain and not to be seen to weaken – wouldn’t budge beyond £345.

In those days, yacht-building was simply priced by overall length, so Hilditch resigned himself to accepting the £345 by agreeing to build a boat with a slightly shorter bow. For all parties, it was a case of cutting off one’s nose off to spite one’s face. The new Island Class yawls were handsome enough. But with a longer bow, they’d have been beautiful.

The island Class yawl Trasnagh, seen here in her first season of 1913, is believed to be the last boat to have been built by John Hilditch. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

The island Class yawl Trasnagh, seen here in her first season of 1913, is believed to be the last boat to have been built by John Hilditch. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

The last of them, Trasnagh herself in 1913, was the last boat to come out of a formerly great yard rapidly tumbling towards extinction. The times were restless politically as well as economically, so it wasn’t a good time to rely on building pleasure boat for a living. And apart from the saturation of the market and the financial demands of building the relatively large Island Class boats, sailing was no longer attracting the same number of newcomers, as rival interests such as motor cars and aeroplanes were taking away many potential enthusiasts,

Yet ironically, had John Hilditch been able to hang on for just another year into the beginning of the Great War of 1914-18, a slew of war work for the Admiralty would have given his yard a new lease of life. But it was not to be. The yard was gone. And soon, so too was the man himself.

But the boats live on. One hundred and two years after John Hilditch’s death, boats that he created are still sailing the seas, and their assembly in Belfast Lough from June 22nd 2016 onwards will be a reminder that, once upon a time, on a site long since covered by Carrickfergus’s re-developed waterfront, John Hilditch and his team built nearly a hundred fine yachts, the best of which have well stood the test of time. All that together with the 150th Anniversaries of two remarkable sailing clubs. For sure, late June on Belfast Lough is going to be one very special time.

Trasnagh restored for her Centenary in 2013

What's The Way For Dublin Bay's Classic Boat Sailors?

Last week's Sailing on Saturday blog about the fate of classic yachts was a revelation about our readership. Although three significant historic vessels in three different and distant locations were involved, it was the news about the re-build of the Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle which drew nearly all the attention. Cork Harbour may indeed be the true capital of Irish sailing, but the sheer size and wealth of the South Dublin population accessing the sea through Dun Laoghaire gives it special power and interest. As someone whose home port is outside Dublin Bay, W M Nixon happily returns to the fray.

It's little wonder that Ireland has won more than her fair share of Nobel Prizes for Literature, yet frequently has to look abroad when boats need to be built. We're great at working words into packages of merchandisable literature or high-flown arguments, but we're maybe not so good at building boats, or even looking after them.

But then, Albert Einstein was a keen sailing man, yet despite his intellectual genius, his boat was always a bit of a mess. So maybe it's all of a piece, that last weekend's story about – among other things – the re-build in France of a classic Dublin Bay 24 of 1948 vintage, has in the space of a few days evoked thousands of beautifully-crafted words in the comment section with enough heat generated to warm a small town. (to read comments scroll to the end of last Saturday's blog here – Ed)

Some of the big beasts of Dun Laoghaire's sailing jungle have enthusiastically thrown their hats into the ring, and already we can imagine some shrewd producer of Cable TV docu-dramas setting out a potential cast list for the likes of Roger Bannon and Hal Sisk, while the mysterious Michael Joseph will be played by The Man In The Iron Mask.

The irony of it all is that all these commentators aspire to the same thing – increased vitality and enthusiasm in Dun Laoghaire sailing. And sometimes, if they would take more time to read each other's detailed comments, they'll find they broadly are advocating the same methods of providing boats which will set the local sailing imagination alight, rather than being just another set of plastic fantastics.

But because of the Irish habit of "wanting nothing to do with that other crowd," a lot of creative diplomacy is needed to harness all this energy. Maybe an intense level of debate is unavoidable. For as we've said of another venerable Irish classic boat class which manages to survive and prosper, it does so by inverting the laws of physics, and relying on friction to create energy.

Let's begin with the most straightforward query – Michael Joseph's first question, posted on Wednesday 15th October, as to why do we think that the setup in Dun Laoghaire is not conducive to the preservation and continuing vitality of a class of 38ft classic wooden yachts, in other words the Dublin Bay 24s?

Well, basically it's because Dun Laoghaire has great difficulty in getting some of its acts together. It's physically a very fragmented sort of place. The relationship of the town with the harbour has always been problematical, and it's difficult to generate a general sense of maritime community which might be conducive to encouraging classic yachts which need to be well loved.

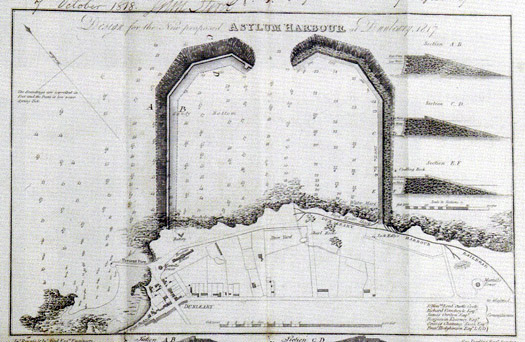

When the plans for the new "Asylum Harbour" were drawn up in 1817, it was seen purely as a shelter facility for shipping caught out in in adverse weather in the Dublin Bay. Although there was a tiny quay at Old Dunleary (the area is still known as The Gut), in the initial plan it was actually shown as being outside the new harbour. The thought that the crews of ships anchored in this new port of refuge might wish to have direct contact with the nearest bit of shore seems if anything to have been actively discouraged.

The proposed pans for an Asylum Harbour in 1817 did not include any suggestions as to possible in-harbour locations for jetties and quaysides, let alone waterfront development, and it actually excluded the small quay at Old Dunleary to the west, though in the final form the West Pier was moved further west to enclose the Old Dunleary pier.

This meant that when the inevitable shoreside facilities began to develop rapidly, it was all on a piecemeal basis. Ideally, when the plan for the harbour was finally agreed, a parcel of property of the same area as the harbour itself should have been secured on the waterfront for the planned development of a complete harbour town. But instead, you got opportunist growth - not really development at all. An unattributed quotation about 19th Century Kingstown, as it had now become, in David Dickson's recently published mighty tome Dublin (Profile Books) tells us much about the official view of the way things had got out of hand in the new seaside town, with speculative developers such as Mr Gresham from the Gresham Hotel putting up terraces of houses every which way:

".....no system whatever has been observed in laying out the town so that it has an irregular, republican air of dirt and independence, no man heeding his neighbour's pleasure, and uncouth structures in absurd situations offending the eye at every turn."

Ouch. For a growing conurbation which prided itself on being called Kingstown, that "republican air of dirt and independence" was a low blow. But as the new railway in 1834 had cut most of the new town off from the sea, an effect which was to become further emphasized by roads running parallel with it, the opportunities for dynamic interaction between town and harbour were restricted. Thus any waterfront space became too valuable to house the workshops of master craftsmen, boatbuilders and shipwrights who might be expected to be readily available to build and maintain local classes of wooden yachts of any significant boat size.

Modern Dun Laoghaire looking northwards, though it should be noted that this photo was taken before the contentious new library was forced into the waterfront between the Royal Marine Hotel and the National Yacht Club. With the water edge's almost exactly marked by the railway and the roads parallel to it, this clearcut division means that, far from the waterfront being part of a shared urban-harbour complex, the complete lack of planning in the early stages has resulted in very little comfortable inter-action between harbour and land, and there is precious little space available for locating specialist small boatyards and marine workshops which would facilitate the continuing good health of substantial wooden classic yachts.

So nowadays, the reality is that basing a cabin sailing yacht of any reasonable size in Dun Laoghaire on a year round basis is too expensive already without the added cost of her being a high-maintenance classic. The best value for money in Dun Laoghaire at the moment is probably provided by a Sigma 33 or a First 31.7 raced as a One Design. Yet in both cases, the necessary membership of one of the waterfront yacht clubs and Dublin Bay Sailing Club, added to the expense of a marina berth and the most basic running costs, means an owner-skipper is shelling out around €10,000 per annum before anything much has been done with the boat.

So although Dublin Bay Sailing Cub works wonders in co-ordinating the racing of hundreds of boats, the survival or otherwise of a class is dictated not by policy decisions on promoting new classes by DBSC, but rather by ruthless market forces, with the sheer expense of sailing from Dun Laoghaire dictating which classes can hang on when times are bad.

The result is that over the years, the surviving classics have become steadily reduced in class numbers, and only the smallest boats survive. With the loss this year of the 17ft Mermaids as an officially recognized Dublin Bay class, as they could no longer guarantee the minimum fleet of five boats, only the 25ft Glens survive from the former serried ranks of several wooden keelboats, and only the 14ft Water Wags survive of the once numerous wooden dinghies.

Yet the growing health of the Water Wags – which can trace their history back to 1887 as the world's first One Design Class - suggests that even in the cut-throat accountancy-led world of Dun Laoghaire Harbour, people still have a natural fondness for classic wooden boats. The current fleet of robust Water Wag dinghies are to a design adopted in 1904, and it adds to their attraction that although they were supposedly designed by local boatbuilder James Doyle, it's generally agreed that the real designer was his talented daughter Maimie.

Mind the gap........ Some of the fleet of a dozen and more classic Waterwags which departed their home waters of Dublin Bay last weekend to race in County Roscommon on the North Shannon's Lough Boderg. Photo: Guy Kilroy

The class have an instinctive sense of their own community, with mutual assistance in maintenance and honing sailing skills a natural part of the healthy mix. One of the factors which has increased their viability is the huge improvement in boat road trailers, for although they remain firmly based in Dun Laoghaire, from time to time you find they've upped and left and gone off for a weekend's racing at some strange and distant location, which might well be described by the management wonks as a bonding exercise

Last weekend, they were having their annual North Shannon Regatta. One of the keenest owners, Guy Kilroy, has a farm in Roscommon on the west shore of Lough Boderg, and the Water Wags descended on him in force. Despite the presence of the great Jimmy Furey building his classic sailing dinghies at Leecarrow on the west shores of Lough Ree, you'd never have thought of Roscommon as a sailing county, but there you go. However, while the coastal Autumn leagues at Crosshaven and Howth saw the seasonal mists soon dispersed, on Boderg in the middle of Ireland it took a long time for the fog to lift. But when it did, the sailing was sublime, and they got in two good races, with four boats level on points, but Ian and Judith Malcolm in the 99-year-old Barbara won on the countback.

Wags-in-a-mist. While the seasonal mists soon cleared at the Autumn Leagues on the coast at Crosshaven and Howth, in the heart of Ireland on Lough Boderg the fog lingered. Photo: Judith Malcolm

Lots of TLC. They may be in the reeds, but the maintenance mustn't be done in a rush.....The high standard of TLC on the Water Wags – the oldest chime in at 110 years – is a wonder to behold. Photo: Ian Malcolm

When all the loving care becomes worthwhile – perfect racing on Lough Boderg last weekend for David McFarland's Moosmie (15) and Vincent Delany's Pansy (3), with Killian Skay's Maureen (29) and Scallywag (44, David Williams and Dan O'Connor) in gentle pursuit. Photo: Guy Kilroy

Maintaining a Water Wag is a very manageable business, but inevitably as the recession recedes, there'll be noises about reviving larger wooden classics, and there's a feeling that the Mermaids aren't completely finished in Dun Laoghaire harbour just yet. There was an interesting twist to this in 2014's Mermaid racing, as the National Championship at Rush was won by Jonathan O'Rourke of Dun Laoghaire's National YC.

Despite being up in Fingal's Rogerstown heartlands where in recent years they've built some supposedly hyper-competitive Mermaids with the clever use of epoxy, Skipper O'Rourke's boat is the 1960 Grieves Brothers built Tiller Girl, which is surely a hopeful sign for the class's future.

The age-defying champion. Mermaid Champion 2014 Jonathan O'Rourke (National YC) with his 1960-built Grieves Brothers boat Tiller Girl. Despite there currently being no racing for Mermaids in Dun Laoghaire, Tiller Girl won the Nationals at Rush even though she was in the area where new supposedly lighter Mermaids, using the exoxy wood system, have recently been built. Photo: W M Nixon

Well, hello Dolly! Named after the world's first cloned sheep, the cloned GRP Mermaid Dolly (white hull) was built in the hope of revitalizing the class, particularly in Dun Laoghaire. But even though she only had a fiberglass hull shell with the rest of her – including the mast – in wood, the new concept was rejected by the class. So Dolly is now based at Sag Harbor in the Hamptons on Long Island in America, where she is much admired, while three of her sisters have proven very to be very durable and effective training boats at a sailing school in West Cork.

Nevertheless, it's at this time of the year that the hassle of maintaining a clinker built wooden boat comes centre stage yet again, and I have to confess that when Roger Bannon produced the fibreglass-hulled Mermaid Dolly, I thought she was a super boat and still do, but the class elders decided otherwise.

Moving on up the size scale, we return to the battleground of the Dublin Bay 21s, still mouldering in a Wicklow farmyard. I only once sailed on one of them under their classic gaff rig complete with jackyard topsail, and despite the enormous spread of cloth, was very impressed by how light and responsive they were on the tiller, but then we were racing in a gentle breeze.

The Dublin Bay 21s await their fate in a Wicklow farmyard

However, this constant refrain about them acquiring dangerous lee helm in strong winds seems to me to be a result of the primitive mainsail arrangement, with the tail of the mainsheet led directly from the counter to cleats on the cockpit coaming. This gave very poor levels of sail control in squalls, and often when the helmsman requested that the mainsheet be quickly but carefully eased to give him better control and keep the boat more upright, it would instead be let go with a run, the mainsail would then be flogging out of control, the close-sheeted headsails would force the bow off, the end of the long mainboom would then hit the water causing the sail to fill with the boat now on a reach, and over and under she'd go.

In a moderate breeze, the Dubin Bay 21s under their original rig undoubtedly carried a small amount of weather helm, and there was no evidence of lee helm at all.

In a moderate breeze, the Dubin Bay 21s under their original rig undoubtedly carried a small amount of weather helm, and there was no evidence of lee helm at all.

Dublin Bay 21 at full cry in the final short in-harbour run from the Coal Harbour buoy to the finish off the club. For this crucial little leg, instant spinnaker setting was essential. It can be noted that the crewmember on the right in the cockpit is trimming the mainsheet by looking aft, the sheet being cleated to the cockpit coaming. In severe weather, this crude method of sheeting could sometimes see the entire sheet being let go completely out of control, whereupon the boat's bow would be forced off by the still-sheeted headsails, the main would then partially fill on the reach as the hyper-long mainboom had started to trail in the sea, and the risk of sinking became very real.

Dublin Bay 21 at full cry in the final short in-harbour run from the Coal Harbour buoy to the finish off the club. For this crucial little leg, instant spinnaker setting was essential. It can be noted that the crewmember on the right in the cockpit is trimming the mainsheet by looking aft, the sheet being cleated to the cockpit coaming. In severe weather, this crude method of sheeting could sometimes see the entire sheet being let go completely out of control, whereupon the boat's bow would be forced off by the still-sheeted headsails, the main would then partially fill on the reach as the hyper-long mainboom had started to trail in the sea, and the risk of sinking became very real.

So it could well be that if a re-built class of Dublin Bay 21s ever emerges, that then they might be given an added safety factor by having the mainsheet led forward, guided close along the underside of the mainboom, and then come down the aft side of the mast to be controlled by a winch on top of the coachroof.

As to whether or not we'll ever see the 21s race again, the odd thing is I think this week's intense exchange here on Afloat.ie may have brought it all a bit nearer. Because if you plough on through the icy politeness of the initial exchanges between Hal Sisk and Roger Bannon, I think you'll discern that they both reckon a cold moulded multi-skin timber hull construction to be a very viable option.

Roger Bannon points out that building a completely new hull on the ballast keel of the original boat is recognized under maritime law as being the continued existence of the same boat, which somehow is an oddly heartening bit of information when you look at the utter dereliction of the DB 21 hulls today.

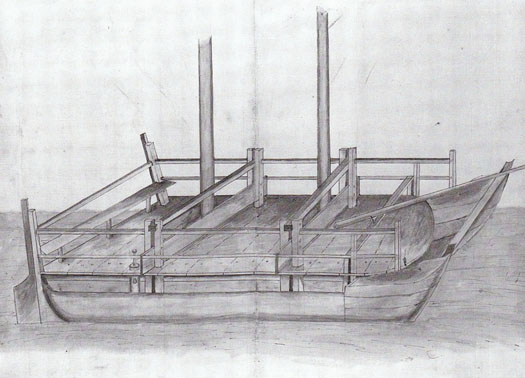

Could this be the future for the Dublin Bay 21s? Beautiful multi-skin construction under way on Steve Morris's 32ft Harrison Butler designed classic at Moyasta near Kilrush. If it's adopted for the revival of the Dublin Bay 21s, as several of the boats would be buit in one batch construction could be facilitated by the inverted hulls being built on a male mould, thereby making the work easier for newcomer to boatbuilding working on a community basis.

Photo: W M Nixon

And as for Hal Sisk and Fionan de Barra, they've been considering seriously the work being done by Steve Morris near Kilrush in building a cold-moulded classic cutter to Harrison Butler's Khamseen design. Steve was the lead builder in constructing the superb gaff cutter Sally O'Keeffe down in West Clare. So when you see his work on his new boat, all things seem possible, particularly if it's agreed that the new Dublin Bay 21s should be cold-moulded in multi-skin timber on inverted hulls in a maritime community project in Dun Laoghaire, as the basic work would be relatively unskilled, and everyone could have a go at it.

For, as the success of the wonderful CityOne dinghy project in Limerick has shown, in sailing the building of the boat can be as much part of the experience as the subsequent time afloat. But if we ever do see the Dublin Bay 21s sailing again, let it please be with the proper rig. Everyone seems to be pussy-footing around the idea of a more easily handled semi-gunter configuration, maybe with just one jib. What's the point of all that? This isn't meant to be Easy Street. Let's have the full jackyard tops'l and cutter rig and all the bells and whistles, or let's not bother at all.

Should the Dublin Bay 21s be re-built, it has been suggested that for ease of handling and project management they might in future use this simpler "American gaff" rig, as seen here on Zanetta which was built on the Clyde in 1918 to the Dublin Bay 21 design.............

,,,,,but here at Afloat.ie, we reckon that would be the wrong approach. If you're going to have a new Dublin Bay 21, then she should have all the classic bells and whistles and more sail than is good for her, just as we see here with the Ringsend-built Innisfallen having a bit of sport with her spinnaker in the 1950s.

#oldestyachtclubintheworld – Following WM Nixon's latest blog on Afloat.ie where he gives an account of early Irish yachts and yachting, leading yachting historian Hal Sisk has added to the story of how the sport was formed with claims the amateur sport of sailing became established in the 1850s on Dublin Bay.

Sisk also reveals that contrary to the conventional foundation myth for yachting, the English did not introduce yacht racing in the 1660s. Instead, a once off race is recorded on Dublin Bay where Sir William Petty wrote that he had successfully matched his experimental 30–ft catamaran on several occasions in the winter of in the winter of 1662/3.

In a written comment at the end of Nixon's Saturday blog: Sailing Artefacts Prove Irish Yacht Clubs Are The Oldest In The World, Sisk also asks how significant were the early yacht clubs and were the early yachts truly leisure craft?

He gives as an example, the Stuart royal yachts that were mini warships, built from funds voted for the Navy and in battle with the Dutch in 1673.

Finally, Sisk says the worldwide sport we know today owes more to the pioneering amateurs of Dublin Bay than to the wealthy yacht owners of the 18th and early 19th century. Thus as well as several spectacular silver trophies, the key figures of the Dublin's Royal Alfred YC gave us in the 1850s to 1870s the following yachting firsts:

--World's First National Yacht Racing Rules and Regulations (published by the RAYC in 1872, adopted by the Yacht Racing Association)

--World's First Offshore Racing Club (1868 to 1922)

--World's First Single and Double handed races (1872)

--World's Premier Amateur Sailing Club (1857--)

Add to that the Water Wags of Dublin giving the world the One Design concept in 1887, and we may well ask who made the greater contribution to our sport and who left the greater lasting influence?

Hal Sisk's full comments can be read a the end of the WMN Nixon's blog here.