Displaying items by tag: Jack Tyrell

A New Tall Ship For Ireland? It's Back to The Future

#tallship – The Tall Ships return to Ireland in spectacular style this summer with a major fleet assembly in Belfast from Thursday 2nd to Sunday 5th July for the beginning of the season's Tall Ships Races, organised by Sail Training International. The seagoing programme will have a strong Scandinavian emphasis in 2015, with the route - some of which is racing, other sections at your own speed – starting from Belfast to go on Aalesund in western Norway for 16th to 18th July, thence to Kristiansand (25th to 28th July), which is immediately east of Norway's south point, and then on to conclude at Aalborg in northern Denmark from 1st to 4th August.

But before leaving Northern Ireland with the potentially very spectacular Parade of Sail down Belfast Lough on Sunday July 5th, the celebrations will be mighty. The fleet's visit will be the central part of the Lidl Belfast Titanic Maritime Festival, which will include everything from popular family fun happenings with concerts and fireworks displays – the full works, in other words – right up to high–powered corporate entertainment attractions.

As for the ships, there will be more than enough for any traditional rig and tall ship enthusiast to spend a week drooling over. In all, as many as eighty vessels of all sizes are expected. But more importantly, at least twenty of them will be serious Tall Ships, proper Class A square riggers of at least 40 metres in length, which is double the number which took part in their last visit to Belfast, back in 2009.

That smaller fleet of six years ago seemed decidedly spectacular to most of us at the time. So the vision of a doubling of proper Tall Ship numbers in Belfast Harbour is something we can only begin to imagine. But when you've a fleet which will include Class A ships of the calibre of the new Alexander von Humboldt from Germany, Norway's two beauties Christian Radich and Sorlandet, the much-loved Europa from the Netherlands, George Stage from Denmark, and the extraordinary Shtandart from Russia which is a re-creation of an 18th Century vessel built for Emperor Peter the Great, you're only starting, as that's to name only six vessels – what we'll be seeing will be a truly rare gathering of the crème de la creme.

So although it would be stretching it to think that a small country like Ireland should aspire to having a major full-rigged vessel, we mustn't forget that for 27 glorious years we did have our own much-admired miniature Tall Ship, the gallant 84–ft brigantine Asgard II. Six-and-a-half years years after her loss, it's time and more for her to be replaced. W M Nixon takes a look at what's been going on behind the scenes in the world of sail training in Ireland and finds that, in the end, we may find ourselves with a ship which will look very like a concept first aired for Irish sail training way back in 1954.

The pain of it. You search out a photo of Shtandart, the remarkable Russian re-creation of an 18th century ship, and you find that Asgard II is sailing beside her

It was while sourcing a photo of Russia's unusual sail training ship Shtandart that the pain of the loss of Asgard II emerged again. It's always there, just below the surface. But it's usually kept in place by the thought that we have to move on, that worse things happened during the grim years of Ireland plunging ever deeper into recession, and that while our beloved ship did indeed sink, no lives were loss and her abandonment was carried out in an exercise of exemplary seamanship.

Yet up came the photo of the Shtandard, and there right beside her was Asgard II, sailing merrily along on what's probably the Baltic, and flying the flag for Ireland with her usual grace and charm. The pain of seeing her doing what she did best really was intense. She is much mourned by everyone who knew her, and particularly those who crewed aboard her. All three of my sons sailed on her as trainees, they all had themselves a great time, and two of them enjoyed it so much they repeated the experience and both became Watch Leaders. It was very gratifying to find afterwards, when you went out into the big wide world and put "Watch Leader Asgard II" on your CV, that it counted for something significant in international seafaring terms.

But as a sailing family with other boat options to fall back on, we didn't feel Asgard II's loss nearly as acutely as those country folk for whom the ship provided the only access to the exciting new world of life on the high seas.

Elaine Byrne vividly recalls how much she appreciated sailing on Asgard II, and how she and her siblings, growing up in the depths of rural Ireland, came to regard the experience of sailing as a trainee on the ship as a "Rite of Passage" through young adulthood

The noted international investigative researcher, academic and journalist Dr Elaine Byrne is from the Carlow/Wicklow border, the oldest of seven children in a farming family where the household income is augmented with a funeral undertaking business attached to a pub in which she still occasionally works. Thus her background is just about as far as it's possible to be from Ireland's limited maritime community. Yet thanks to Asgard II, she was able to take a step into the unknown world of the high seas as a trainee on board, and liked it so much that over the years she spent two months in all aboard Asgard II, graduating through the Watch Leader scheme and sailing in the Tall Ships programmes of races and cruises-in-company

Down in the depths of the country, her new experiences changed the Byrne family's perceptions of seafaring. Elaine Byrne writes:

"Four of my siblings (then) had the opportunity to sail on Asgard II. If it were not for Asgard II, my family would never have had the chance to sail, as we did not live near the sea, nor had the financial resources to do so. The Asgard II played a large role in our family life as it became a Rite of Passage to sail on board her. My two youngest siblings did not sail on the Asgard II because she sank, which they much regret".

She continues: "Apart from the discipline of sailing and the adventure of new experiences and countries, the Asgard brought people of different social class and background together. There are few experiences which can achieve so much during the formative years of young adulthood"

That's it from the heart – and from the heart of the country too, from l'Irlande profonde. So, as the economy starts to pick up again, when you've heard the real meaning of Asgard II expressed so directly then it's time to expect some proper tall ship action for Ireland in the near future. But it's not going to be a simple business. So maybe we should take quick canter through the convoluted story of how Asgard II came into being, in the realization that in its way, creating her successor is proving to be every bit as complex.

As we shall see, the story actually goes back earlier, but we'll begin in 1961 when Erskine Childers's historic 1905-built 51ft ketch Asgard was bought and brought back by the Irish government under some effective public pressure. It was assumed that a vessel of this size – quite a large yacht by the Irish standards of the time – would make an ideal sail training vessel and floating ambassador. It was equally assumed that the Naval Service would be happy to run her. But apart from keen sailing enthusiasts in the Naval Reserve - people like Lt Buddy Thompson and Lt Sean Flood – the Naval Service had enough on its plate with restricted budgets and ageing ships for their primary purpose of fishery patrol.

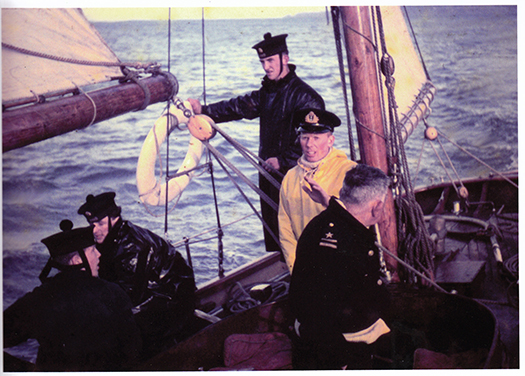

Aboard the first Asgard in 1961 during her brief period in the 1960s as a sail training vessel with the Naval Service – Lt Sean Flood is at the helm

So Asgard was increasingly neglected throughout the 1960s until Charlie Haughey, the new Minister for Finance and the only member of Government with the slightest interest in the sea, was persuaded by the sailing community that Asgard could become a viable sail training ship. In 1968 she was removed from the remit of the Department for Defence into the hands of some rather bewildered officials in the Department for Finance, and a voluntary committee of five experienced sailing people - Coiste an Asgard - was set up to oversee her conversion for sail training use in the boatyard at Malahide, which just happened to be rather less than a million miles from the Minister's constituency.

Asgard in her full sail training role in 1970 in Dublin Bay

Asgard was commissioned in her new role in Howth, the scene of her historic gun running in 1914, in the spring of 1969. Under the dedicated command of Captain Eric Healy, the little ship did her very best, but it soon became obvious that her days of active use would be limited by reasons of age, and anyway she was too small to be used for the important sail training vessel roles of providing space to entertain local bigwigs and decision-makers in blazers.

By 1972, the need for a replacement vessel was a matter of growing debate in the sailing community, and during a cruise in West Cork in the summer of 1972, I got talking to Dermot Kennedy of Baltimore out on Cape Clear. Dermot was the man who introduced Glenans to Ireland in 1969, and then he branched out on his own in sail training schools. A man of firm opinions, he reacted with derision to my suggestion that Asgard's replacement should be a modern glassfibre Bermudan ketch, but with enough sails to keep half a dozen trainees busy.

"Nonsense" snorted Dermot. "Ireland needs a real sailing ship, a miniature tall ship maybe, but still a real ship, big enough to carry square rig and have a proper clipper bow and capture the imagination and pride of every Irish person who sets eyes on her. And she should be painted dark green just to show she's the Irish sail training ship, and no doubt about it".

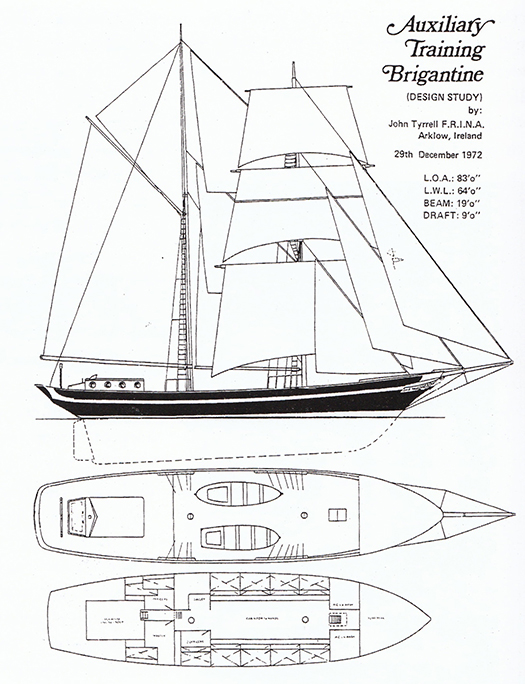

Some time that winter I simply mentioned his suggestions in Afloat magazine, and during the Christmas holidays they were read by Jack Tyrrell at his home in Arklow. During his boyhood, in the school holidays he had sailed with his uncle on the Arklow schooner Lady of Avenel, and it had so shaped his development into the man who was capable of running Ireland's most successful boatyard that he had long dreamed of a modern version of the Lady of Avenel to be Ireland's sail training ship.

The inspiration – Jack Tyrrell's boyhood experiences aboard Lady of Avenel inspired him to create Ireland's first proper sail training ship

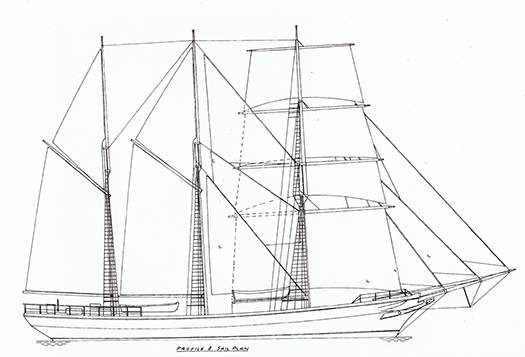

In fact, in 1954 he had sketched out the plans for a 110ft three masted training ship, but Ireland in the 1950s was in the doldrums and the idea got nowhere. Yet the spark was always there, and it was mightily re-kindled by what Dermot Kennedy had said. So at that precise moment, the normal Christmas festivities in the Tyrrell household were over. They'd to continue the celebrations without the head of the family. The great man took himself off down to the little design office in his riverside boatyard, and in clouds of pipe tobacco smoke, he re-drew the lines of the 110ft three master to become an 83ft brigantine, the size reduction meaning that the shop would only need a fulltime crew of five.

Working all hours, he had the proposal drawings finished in time to rejoin his family to see in the New Year. And in the first post after the holiday, we got the drawings at Afloat, and ran them in the February 1973 issue.

Jack Tyrrell's proposal drawings for the new brigantine, as published in the February 1973 Afloat

In Ireland then as now, most politicians had inscribed in their heads the motto: "There's No Votes In Boats". So after Charlie Haughey had fallen from favour with the Arms Trial of 1970, Coiste an Asgard became an orphan. But 1973 brought a new government, and there was one cabinet minister in it who was proud to proclaim his allegiance to the sea.

Unfortunately for the respectability of the maritime movement in Ireland, our supporters in the higher echelons of politics have often tended to be from the colourful end of the political spectrum, whatever about their placing in the left-right continuum. Thus it was that, at mid-morning on St Patrick's Day 1973, I got an ebullient phone call and an immediate announcement, without the caller saying who he was. "Winkie" he bellowed, "That ship is going to be built. I'll make sure of it. I've just made a ministerial decision".

It emerged that it was our very own new Minister for Defence, Patrick Sarsfield Donegan TD. The enthusiasm for the new ship, engendered by studying Jack Tyrrell's drawings, led to a snap decision which stayed decided, and it all happened in the Department for Defence.

However, it was 1981 by the time the ship was launched, and she looked rather different from Jack Tyrrell's preliminary drawings, though the basic hull shape built in timber was the same sweet lines as originally envisaged, so she was able to sail like a witch. But as for her supporters at Government level, the non-stop cabaret continued. Charlie Haughey had regained power, and by 1981 he was Taoiseach. It was he who had seen to it that the Department of Defence continued to look after the Asgard II project with support from another sailing TD who might not have seen eye–to-eye with him on other matters, Bobby Molloy of Galway.

Asgard II in her finished form

So on a March day in 1981, almost exactly twelve years after he'd commissioned the original Asgard in her new role as a sail training vessel, Charlie Haughey took it upon himself to christen the new Asgard II in Arklow basin. And the champagne bottle refused to break. Five or six time he tried, but with no success.

Showing considerable grace under pressure and observed by a large crowd, he quietly took his time undoing all the ribbons and paraphernalia on the big bottle. Then he marched with it up to the new flagship's stem, and hit it a mighty double-handed wallop. The bottle exploded that time, with no mistake. And apart from the usual Haughey growl to those nearby about the idiocy of whoever forgot to score the champagne bottle beforehand, it was all done with the best of humour.

For most of her subsequent career, there's no doubt Asgard was a lucky and very successful vessel. Yet when her demise came, you couldn't help but think of the old notion that if the champagne bottle doesn't break first time, then she'll ultimately be an unlucky ship.

But there are more prosaic explanations. With a limited budget and every penny being scrutinized, Jack Tyrrell and his men had to build Asgard II in fishing boat style, which is fine within its proper time span, but that time span is really only twenty years, maybe thirty if the ship gets extra care. But with her fishing boat hull carrying a demanding brigantine rig, although she always looked immaculate, Asgard II was starting to show her age in the stress areas.

By 2005 there was serious talk about the need to plan for a replacement. When her skipper Colm Newport was told to renew her rig as the original spars were clearly well past it, he meticulously searched the best timber yards at home and abroad and when she got her new rig – it was 2006 or thereabouts – I wrote an only slightly tongue-in-cheek article suggesting that now was the time to replace her old tired wooden hull with a new steel one to the same Jack Tyrrell lines, but utilising the excellent new rig and as many of the fixtures and fittings as were still in good order from the original ship.

To say the response was negative is understating the case. People's attachment to Asgard could only imagine a wooden ship. It was the end of any meaningful debate. So things drifted on, with each new government seemingly even less interested in maritime matters generally, and sail training in particular, than the one before.

In September 2008, Asgard started taking in water while on passage with a crew of trainees towards La Rochelle for a maritime festival following which - while still in La Rochelle – it was planned that she would be lifted out for a thorough three week survey and maintenance programme.

Asgard's accommodation worked superbly whether at sea or in port. But the fact that so much was packed into a relatively small hull meant that some areas were almost inaccessible for proper inspection

It might have been the saving of her. But it was not to be. It's said that it was a failed seacock which caused the catastrophic ingress of water. She was a very crowded little ship, she packed a lot into her 84ft, so some hull fittings were less accessible internally than they would be in a more modern vessel, and may have deteriorated to a dangerous level. But if, as some would propose, she hit something in the water which caused a plank to start, then the fact that nobody aboard was aware of any impact suggests that the time for a major overhaul, and preferably a hull replacement, was long overdue.

The moment Asgard II sank, she ceased to have any future as a sail training vessel, and there was no real official interest in her salvage. You simply cannot take other people's children to sea on a salvaged vessel of doubtful seaworthiness. And as it happens, the sinking came at exactly the time the Irish economy fell of a cliff. So although after an enquiry the Government accepted a €3.8 million insurance settlement, in the end, despite assurances to the contrary, it disappeared into the bottomless pit which was the national debt, and within a year Coiste an Asgard was wound up with its records and few resources incorporated into a new entity, Sail Training Ireland.

The plot takes a further macabre twist in that, shortly after the loss of Asgard II, the Northern Ireland Sailing Training ketch was also lost after hitting a rock on the Antrim coast. From having two popular and well-used sail training vessels in the middle of 2008, within a year Ireland had no official sail training vessels at all.

Yet though the flame had been largely subdued, there were those who have kept the faith, and gradually the sail training movement is being rebuilt. Sail Training Ireland is the frontline representative for around five different organisations, being the official affiliate of Sail Training International, and it has a busy programme of placing trainees in ships which operate at an international level, in which the Dutch are supreme.

In Ireland at the moment, the only sail training "ship" is the schooner Spirit of Oysterhaven, run by Oliver Hart and his team from their adventure centre near Kinsale. In fact, Spirit – you can read about her in Theo Dorgan's evocative book Sailing For Home (Penguin Ireland 2004) – really is punching way above her weight in representing Ireland in a style reminiscent of both the Asgards.

Spirit of Oysterhaven has been doing great work in keeping sail training alive in Ireland

But having the ship is one thing, paying the fees for the trainees to be aboard is something else, and sail training bursaries are one of the key areas of expansion in current maritime development in Ireland. There was an unusual turn to this in 2014 when somebody came up with the bright idea of using Irish Cruising Club funds (which are generated by the surplus from the voluntary production of the club's Sailing Directions) to provide bursaries for youngsters to take part in last summer's ICC 85th Anniversary Cruise-in-Company along the southwestern seaboard on Spirit of Oysterhaven.

The idea worked brilliantly, and this concept of neatly-tailored sail training bursaries is clearly one which can be usefully developed. But still and all, while it's great that young Irish people are being assisted in getting berths aboard charismatic vessels like Europa, the feeling that we should have our own proper sail training ship again is gradually gaining traction, and this is where the Atlantic Youth Trust comes in.

The AYT had its inaugural general meeting in Belfast as recently as the end of September 2014, so it may not yet have come up on your radar. But as it has emerged out of the Pride of Ireland Trust which in turn emerged from the Pride of Galway Trust, you'll have guessed that Enda O'Coineen and John Killeen are much involved, and they've roped in some seriously heavy hitters from both sides of the border, either as Board Members or backers, and sometimes as both.

The cross-border element is central to the concept of building a 40 metre three-masted barquentine, a size which would put her among the glamour girls in Class A, and could carry a decidedly large complement of 40 trainees, even if you're inevitably talking of stratospheric professional crewing costs.

However, by going straight in at top government level on both sides of the border, the AYT team are finding that they're pushing at a door which wants to open, particularly after the new Stormont House agreement was reached in the last days of 2014 to bring a more enthusiastic approach both to cross-community initiatives in the north, and cross border co-operation generally.

Who knows, but if they can succeed in getting cross-community initiatives working in Northern Ireland, then they may even be able to swing some sort of genuine Dublin-Cork shared enthusiasm in the Republic, for I've long thought that one of the factors in holding back many maritime initiatives in Ireland is that, while Dublin may be the political capital, Cork is quietly confident it's the real maritime capital, and does its own thing.

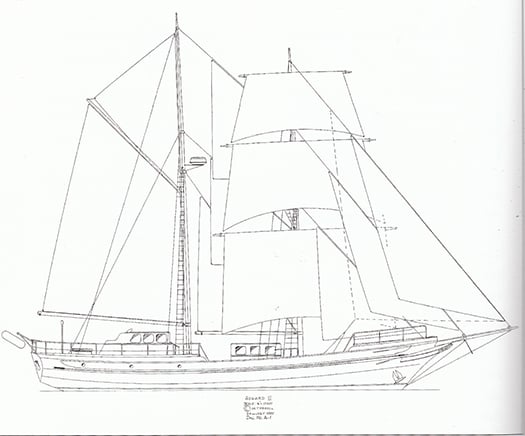

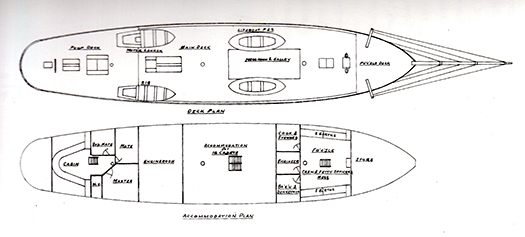

Be that as it may, the AYT have done serious studies, and their conclusion is the best scheme to learn from is the Spirit of Adventure programme in New Zealand. This is where the feeling of going back to the future arises, for in looking at photos of their ship Spirit of New Zealand, there's no escaping the thought that you're looking at Jack Tyrrell's concept ship of 1954 brought superbly to life.

Spirit of New Zealand

Spirit of New Zealand almost seems like a vision of 1954 brought to life...

.....and that vision is Jack Tyrrell's 1954 concept for a 110ft sail training ship

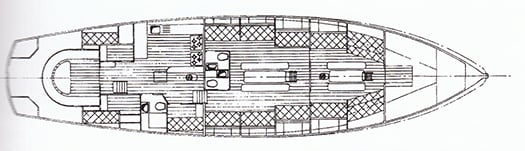

The 1954 accommodation drawings for the 110ft ship hark back to a more rugged age. Imagine the difficulties the ship's cook would face trying to get hot food from his galley on deck amidships all the way back to the officers in their mess down aft

We needn't necessarily agree with all the AYT's basic thinking For instance, they assert that Ireland is like New Zealand is being an isolated smallish island. It depends what you mean by "isolated". Those early sail training pioneers, the Vikings, certainly didn't think of Ireland as isolated. They thought it was central to the entire business of sailing up and down Europe's coastline.

Thus any all-Ireland sail training vessel would be expected to be away abroad at least as much as she'd be at home, whereas Spirit of New Zealand is usually home – the season of 2013-2014 was the first time she'd been to Australia since 1988, when she was in the fleet with Asgard II for the First Feet celebrations.

In New Zealand, she's a sort of floating adventure centre, and a large tender often accompanies her to take the trainees to the nearest landing place for shoreside adventures, for it's quite a challenge keeping 40 energetic young people fully occupied.

In Europe, that's where the sail training races come in. Time was when the racing aspect was down-played. But there's nothing like a good race to bring a mutinous crew together, and the recently-published mega-book about the world's sail training vessels, Tall Ships Today by Nigel Rowe of Sail Training International, quite rightly devotes significant space to everything to do with the racing.

Thus if we do get a new sail training ship for Ireland, she'll have to sail well and fast. That was Asgard II's greatest virtue. For there is nothing more dispiriting for troubled young folk than to find themselves shackled to the woofer of the fleet. Yet you'd be pleasantly surprised by how previously disengaged youngster can become actively and enthusiastically involved when they find that they're being transformed from scared and seasick kids into members of a winning crew.

So now, the 64 thousand dollar question. The cost. It's rather more than 64 thousand. AYT reckon they'll have to come up with a final capital expenditure of €15 million to build the ship and get her into full commission with proper crewing and shoreside administration arrangements in place. But after that – and here's the kernel of the whole concept – they reckon that the running costs will come out of existing government expenditure already in place and used every year for education, youth training, sporting facilities, social development and so forth.

So their pitch is that if the governments north and south come up with funding to support substantial donations already proposed for AYT by various benevolent national and international bodies, then once the ship is in being, she will generate her own income in the same way as vessels like Europa and Morgen Stern are already doing in mainland Europe.

And it's to the heart of mainland Europe that they'll be looking for design and contruction, as it's the Dykstra partnership which will be overseeing the design, and their ship-build associate company Damen will likely do the construction work, though one idea being floated is that Damen might provide a flatpack kit for the vessel to be built in steel in Ireland.

Those of us who dream of Asgard II being built anew will find all this a bit challenging to take on board. My own hopes, for instance, would still be to build Asgard II again to Jack Tyrrell's lines, but with the hull constructed in aluminium. It would be expensive as it would need to be double-skin below the waterline, but the ship's size would be very manageable with a professional crew of just five, while she'd sail like a dream And proper top-class marine grade aluminium seems to last for ever, as naval architect Gerry Dijkstra (his surname is slightly different from that of the partnership) himself shows with his remarkable cruises with his own-designed alloy 54-footer Bestevaer.

A man who knows what he's doing. This is Gerry Dijkstra's own extensively-cruised alloy-built 54 footer Bestevaer. The name translates not as "Best ever", but either as "best father" or "best seafarer", and was the name of affection given to the great Admiral de Ruyter by his loyal crews

Whatever, the good news is that things are on the move, and we wish them well, all those who have kept the Irish sail training flame alive through some appalling setbacks. Now, it really is the time to move forward. And if we do get a new ship, why not call her the Jack Tyrrell? He, of all people, was the one who kept the faith and the flame alive.

- Tall ship

- Belfast

- Jack Tyrell

- Kristiansand

- Aalesund

- Titanic

- maritime

- Class A

- square riggers

- George Stage

- Alexander Von Humboldt

- Christian Radich

- Sorlandet

- Shtandart

- Brigantine

- Asgard II

- Elaine Byrne

- Erskine Childers

- Sean Flood

- Naval

- Afloat magazine

- boatyard

- sail training ship

- Coiste an Asgard

- Charlie Haughey

- Colm Newport

- Irish Cruising Club

- Spirit of Oysterhaven

- Enda O'Coineen

- John Killeen

- Dykstra

Diving Asgard II

In September 2008 an iconic part of maritime Ireland silently and tacitly slipped beneath the surface of the Bay of Biscay near the idyllic island of Belle Isle writes Timmy Carey.

Asgard II was on a journey from Falmouth to La Rochelle for routine maintenance when it would succumb to its fate of a watery grave, thankfully captain Colm Newport was able to safely abandon the ship with the entire crew of 25.

Since 1981 Asgard II a beautiful brigantine designed by Jack Tyrell and built in Arklow had served the Irish nation with distinction all over the globe, providing sail training for over 10,000 people; the image of the bright green hull and white sails becoming synonymous with Irish sailing.

Main: Asgard's wheel prior to removal. Asgard campaigner Captain Gerry Burns (left) holds Asgard's bell with diver Eoin McGarry and the Tricolour defiantly draped on Asgard II

In addition to such a proud history, Asgard II also carried on the name and traditions of Asgard; which played such a pivotal role in Irish history and in the foundation of the state. In Norse religion Asgard was the home of the Norse gods and it is fitting that a vessel with such an auspicious name would later be called "the harbinger of Irish freedom" by the President of Ireland Eamonn De Valera.

Asgard was built in 1905 in larvik and was a wedding gift from Dr and Mrs Hamilton Osgood of Boston to their daughter Mary and her husband Erskine Childers (the father of the future president of Ireland). In a magnificent feat of seamanship (which was reminiscent of his famous novel the riddle of the sands) Erskine Childers in the company of his wife and others expertly collected arms from Hamburg and landed them in Howth on the 26th of July 1914 for the Irish volunteers. In one of the great ironies of Anglo-Irish history Erskine Childers a decorated British war veteran would become an avowed Irish republican and would play a crucial role in the struggle for independence as minister for propaganda (being very highly thought of by both Eamonn De Valera and Michael Collins); before being executed in the Irish civil war.

In 1961 the Irish government purchased the vessel for sail training and in 1968 Coiste and Asgard was founded and was assigned responsibility for the vessel. With the launch of Asgard II, the original Asgard was transferred to the national museum where it has been expertly restored to its original glory and will in the future be available for general viewing.

With such a rich maritime heritage and being so deeply engrossed in Irish history popular view in late 2008 was that the Irish government would salvage Asgard II as a symbol of Irish pride; alas it would later be decided by the Irish government to abandon Asgard II with the uniquely Irish bowsprit of Grainne Uaile condemned to a permanent watery grave on foreign shores.

As with many diving expeditions, they often begin with a simple conversation and one late night a phone call from Eoin McGarry would begin with "what do you think of diving the Asgard II next year". Soon the idea generated its own momentum and a small team of Irish trimix divers (all of whom are CFT members) was assembled and preliminary plans were made for July 2010.

Despite the fact that no permission was necessary to dive the vessel under Irish or French law, it was decided to notify the Irish government of dive teams intentions to video the wreck and recover some of the artefacts for the Irish people. On contacting Coiste an Asgard the reaction of the board was very negative indicating that the artefacts were of little value and that due to the depth involved they were not in favour of any dives taking place.

A little disillusioned it was decided to make representations directly to the Minister for Defence and soon a government TD with a real interest in Irish history discussed the idea with the Minister for Defence Willie O Dea.

The ships name looming out from the darkness

In early February the dive team would receive a personal letter from the minister indicating that "enquiries are being made into the matter and I will write to you again shortly". In addition a TD had also confirmed to the dive team that the minister had indicated that he thought it was a great idea and wished the dive team well. Unfortunately within a very short time period the minister had to resign and the dive team received no further correspondence.

With the Irish government engrossed in an economic recession of epic proportions, the dive team decided to proceed before the ships artefacts were removed by foreign dive teams and lost to the state forever.

With time ticking by the final team of Eoin Mc Garry as expedition organiser, Brendan Flanagan of Longford Sub Aqua club, Phil Murphy and Frank McKenna both of Kilkenny Sub Aqua and myself were assembled as the bottom divers. With an emphasis on keeping the costs down as the divers would be financing the trip, the decision would eventually be made to have one cover diver to help the divers kit up and look after all the surface logistics; this would also allow all the dive team travel together in the one vehicle and reduce the travel costs. Being a qualified mixed diver as well as native of Brittany; Stephane Portrait of Blackwater Sub Aqua Club would become an essential member of the dive team without whom the trip could not have been successful.

Over the coming months Stephane and Eoin would work tirelessly on the logistics, which would be vastly more onerous and detailed than an expedition to the Lusitania. As well as the small issues of organising ferries, accommodation, a dive centre and a dive boat; the dive team would also notify in writing the local mayor of Belle Isle, the local tourist office, the local lifeboat and the admiral of the French national lifeboat institution in Paris, the local council and the head admiral of the Atlantic fleet of the French navy of the dive teams intentions.

Our dive boat skipper Yann Quere being the secretary of the French national sailing organisation and a Moniteur 3 with FFESSM (the French equivalent of CFT in CMAS), would be of huge assistance and confirmed to the dive team that there were no restrictions in diving the wreck. In addition the Irish government had not even requested an exclusion order be placed on the site to preserve the Asgard II, meaning it could be legally dived by any dive team at any time.

During the last few weeks endless hours would be spent reviewing the vessels plans, photographs and video clips; trying to decide what obstacles could lay ahead in trying to video and photograph the wreck as well as removing the bell, helm and compass. Eoin would even go so far as contacting Tyrell's to get the specifications of how the wheel was fitted and what size bolts were used to bolt the bell on.

A specialist dive tool bag was then assembled with all anticipated tools colour coded and placed into the bag in the order of their anticipated use; to try and eliminate wasting any precious bottom time. Only a few weeks to go and word came that a French technical dive team also had their eyes set on the Asgard II, would we arrive to late and would all the artefacts have disappeared into the possession of French or British divers; only time would tell.

Being Jury president of the CFT Moniteur 3 test on Inisboffin the day before the trip to France, my preparation time was hardly ideal; getting home after 10 pm on Friday then having to blend several mixes and assemble camera and rebreather equipment; grab a precious five hours sleep and head for the ferry. Seeing familiar faces of friends and dive buddies all thoughts of fatigue soon evaporated in anticipation of a good weeks diving. During the last week Paddy Agnew also joined the group and would assist Stephane on the surface during the course of the week.

Arriving in the idyllic harbour of Belle Isle the sight of the Irish Tricolour flying from the tourist office on our behalf was a good omen. That evening our skipper told us the water would be warm, the sea flat calm and visibility would be at least 10 meters with ambient light at depth; and we headed to bed in good spirits for an early start. Leaving the harbour with a strengthening breeze we would soon be greeted by a stiff force five and with cylinders rolling around at the stern of our dive boat; conditions were marginal as a small blob at 84 meters showed up on the screen of the GPS.

Our next concern would be the number of prawn trawlers that were fishing quite close by in the direction we anticipated our decompression station moving. With the Bay of Biscay having notoriously unpredictable weather it seemed that we would be treated to diving conditions more reminiscent of the south coast of Ireland. After an arduous time kitting up in a pitching sea in a dive boat, which doesn't normally cater for technical divers; the cooling effect of the sea came as welcome relief as Eoin Mc Garry and I dived first. Eoin would be taking video footage and I would be taking stills with my Ikelite camera housing rated to 60 meters, hopefully it would not leak at 84 metres! (at least the strobe was rated to 90 meters).

Dropping through layers of water the temperature soon dropped from 19 on the surface to 9 degrees Celsius at depth, the biggest surprise however being the visibility. Beyond 60 meters ambient light disappeared and visibility reduced to less than 1.5 meters; Irish diving conditions indeed. Landing on the Asgard II we could immediately see that our anchor line was perilously attached to the wreck and in danger of coming loose: something that was soon rectified. After adapting ourselves to the conditions it was good to see that my camera was surviving at 9 bar (at least for the moment) and we soon set off taking footage with Eoin taking video. Dropping down past the stern came the worm encrusted letters of Asgard II and swimming the length of the vessel it was soon apparent that she was in a sorry state. Both masts had collapsed and she had been badly damaged by trawlers; with one mast landing on the compass binnacle and the roof of the chart completely missing and almanacs aplenty neatly stacked in the shelves.

Amid the books and almanacs and nestled with a menacing grimace a large conger eel now stood sentinel in its new citadel. At the bow area it was a sorry sight to see the bowsprit of Grainne Uaile partially hidden by old sail, doomed forever to the seafloor. Swimming astern the sight of the ships helm still lashed was an amazing image that would cause all divers to become exuberant and all too soon our precious bottom time had elapsed and it was time for the mandatory 2 hours of decompression. Passing the second dive team who were also taking video footage the warm thermo clime was a welcome change from Irish diving conditions, but a strong surface current soon tempered that dramatically.

Back at the decompression station it was a strange sight to see that the strength of the current had orientated the decompression station at a 45-degree angle and instantly knew that the first hours decompression would be far from comfortable (until the second dive team had set the decompression station free in the current). Looking across at Eoin I could see the sight of the ships compass nestled safely in a bag, eliminating one of the objectives for day two. Surfacing to warm sunshine and with greatly moderated sea conditions we were soon planning dive objectives for day 2, pondering the difficulties of removing the ships bell and helm.

On unloading the boat back at Belle Isle we would have two groups of visitors, both unexpected. The first group were survivors of the sinking who had returned to Belle Isle sailing aboard the magnificent Le Belem and soon we were showing them the footage of the vessel they so hastily had to abandon.

The sight of two gendarmes taking to Stephane had the rest of us wondering what was happening, when it quickly emerged that a complaint had been received by the French police from an Irish government agency asking for the diving to be halted. While the rest of us blended gas and organised logistics for day two, Eoin and Stephane had very cordial discussion with French gendarmes who said we might not be able to dive the wreck later in the week.

The next morning with a 6 am start we were soon heading for the wreck site (with the Irish tricolour again flying from our dive boats mast) and were soon onsite. With the possibility of only one dive left on the Asgard II, dive objectives had to be reassigned and all divers were again assigned to two dive teams and we were soon descending a shot line in strong currents.

Approaching the ships hull seeing bubbles coming from my cameras strobe were not a welcome sight and I wondered would it work filled with seawater and found it did. The camera housing rated to 60m meters survived both dives unscathed; with the expert advice I had received on underwater photography earlier in the year from Ivan Donoghue, Simon Carolan and Nigel Moyter proving invaluable on the trip.

During this dive the dive team would again get video footage, which was given to the marine casualty investigation board for their report as well as getting more stills footage. Frank Mc Kenna soon had the ships bell and bracket removed and soon it was attached to a lifting bag and heading for the surface 84 meters above. Eoins' huge amount of prior research was soon hugely rewarded when the ships helm was also heading to the surface where Stephane Portrait was waiting to recover them.

The final act of the dive team would be to leave an Irish tricolour on a vessel whose name has such symbolism in Irish history, when Irish men and women overcame impossible odds to defeat the greatest empire on the globe to establish an Irish state after 700 years of struggle. The tricolour left draped on the wreck had been a gift from an ex member of the Irish Defence Forces and had last flown over and Irish Military Establishment and would serve as a fitting tribute to a vessel that had so eloquently represented Ireland in a maritime setting. Back aboard our dive vessel it was good to see that everyone had completed their decompression safely and that all objectives had been completed, with Stephane doing Trojan work for the bottom divers.

Once back ashore we would be astounded to hear of sensationalist newspaper headlines back home; giving a completely inaccurate version of events. That evening Eoin and Stephane would declare the artefacts to the equivalent of the French receiver of wrecks and would be told that the matter had been referred to the commodore of the local French naval base in Brest.

The following day the gendarmes would give the dive team a copy of a fax from the French naval base which confirmed that the dive team had broken no laws French or otherwise as we had known all along and the French gendarmes apologised for any inconvenience caused (that they had been acting on a fax from an Irish government body which was furnished to the dive team) and wished the dive team well.

Over the next few days of pleasure diving shallower wrecks two surprises would arise; the first that the visibility at the other end of the island was in stark contrast to that where the Asgard II lies and was typically twenty meters at depth!!! and secondly that the artefacts that we had previously been told were valueless were now suddenly of huge interest to Coiste an Asgard. Indeed it would puzzle everyone on the dive team at how helpful the French authorities were which was in stark contrast to their Irish counterparts; whom it would seem would have preferred to see these items disappear into the hands of continental or British dive teams. In the interim Eoin had got expert archaeological opinion in how best to preserve the wheel and spent a considerable sum of his own money in making a specialist box to ensure we could transport it in a wet condition back to Ireland.

Once back home the huge cascade of congratulatory messages to the dive team was a nice boost and made all the financial and personal sacrifice very worthwhile, as the volume of people with an interest in Irish maritime affairs soon became apparent. Back on Irish soil, the artefacts were registered with the Irish receiver of wrecks and handed over to him in custody as per maritime and salvage law. Hopefully in time these symbols of Irish maritime history and pride will be put on permanent display in a fitting venue such as the national museum next to the original Asgard or in Dun Laoghaire at the national maritime museum; where the 10,000 trainees who first learned to sail a tall ship aboard Asgard II can again hold that famous wheel or ring the bell.