Displaying items by tag: Royal Ulster Yacht Club

Belfast Lough Sailing Story Seen In A New Light After Princess Anne Gives Royal Lead

Maybe it’s time and more to see sailing and its story – and particularly the complex history of Irish sailing north and south – in a new light. This year, the historical sailing focus is on Northern Ireland, where the Royal Ulster Yacht Club and Carrickfergus Sailing Club are both celebrating their 150th Anniversaries. For RUYC, this has already resulted in a Royal visit in recent days. But it was a Royal visit with a difference. W M Nixon takes a look at how the sailing celebration scene in Northern Ireland is reflecting an increasingly nuanced interaction with our sailing history, and how this in turn can affect how we interpret the story of sailing.

It was certainly a Royal visit with a difference, as it usually is with Princess Anne. Whatever your views on Royalty in any of its manifestations, purposes and functions, it has to be accepted that this is one very hard-working member of the British Royal family. When she’s President or Patron of some national or international organisation, it will almost inevitably be because she’s personally interested in the activities involved. And being an involved and can-do person, rather than a stand-aloof sort of figurehead, you’ll find that she was, and probably still is, a very enthusiastic participant in at least some specialized activity within the broad spectrum of the organisation’s remit.

Thus the fact that she and her husband are keen cruising enthusiasts who have in recent years moved up to the Rustler 44 Ballochbuie – which they base in Scotland - after many years with a Rustler 36, means that her role as President of the Royal Yachting Association is something with real meaning. When she goes to a yacht or sailing club, while inevitably there’ll be that slightly giddy mood which always accompanies the presence of Royalty, there’s no escaping the fact that this is a working visit. It’s a long way from being purely ceremonial – people find themselves talking about their own sailing, and sailing in general, both how it is run, and where it is going.

Serious business. Princess Anne in earnest discussion with Gordon Finlay, RUYC Honorary Archivist. On the left is Peter Ronaldson, former Vice Commodore RUYC and former Commodore Irish Cruising Club.

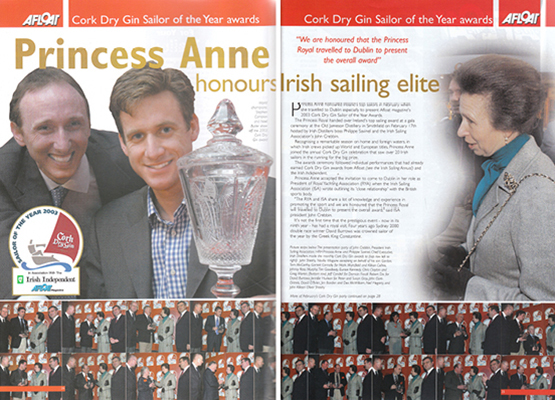

This isn’t the first time in Ireland north and south that Irish sailing has experienced the inspirational results of involvement by the Princess Royal. Twelve years ago, early in 2004, Afloat and the ISA got the word that a Big Idea floated some time earlier might just have wings.

In those days, our annual “Sailor of the Year” and “Sailors of the Month” awards were on a much more commercial basis, as they were strongly sponsored by Cork Dry Gin. It may now seem light years away, that a drinks company could so publically sponsor a major sports awards ceremony. But such was the case – they’d been doing it since 1996.

By 2004 it had become a very smoothly-organised affair, staged in the Irish Distillers Jameson Centre in Dublin where they even have a usefully-sized theatre/cinema which was ideal for this ceremony, and very efficiently organized as an event with Deirdre Farrrell, Irish Distillers’ in-house PR person, skillfully pulling it all together. Afloat and the Irish Sailing Association provided the details on who got what in the awards area, and Paddy Boyd, Secretary General of the ISA, performed as an extremely competent Master of Ceremonies while my job in concert with David O’Brien was to enumerate each of the citations for the usual multiplicity of awardees.

Thanks to the enthusiastic and directly-involved support of the sponsors, this annual show became such a byword for a well-run and popular yet efficiently-controlled event that we found ourselves playing a role in the much wider national and international scene.

The often difficult relations between the Republic of Ireland and Britain had started to thaw quite markedly after the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, and it was obvious that for this normalization process to continue to develop in a meaningful way which would have a resonance for many points of view within Ireland, in due course a Royal Visit to Ireland by the Queen would have to be on the cards.

So the buildup towards such a visit was set in place with quiet appearances at some relatively low key events – international charities were very useful for this – by some minor members of the Royal Family. The process then moved on, and when someone in the ISA/Afloat setup suggested that in order to add that extra zing to the annual Irish sailing awards, we should ask the Princess Royal in her capacity as President of the UK’s Royal yachting Association to do the honours, ISA President John Crebbin and Paddy Boyd made a discreet enquiry to the British Embassy, and found they were pushing at an open door.

Irish sailing’s idea fitted in very neatly with the development and implementation of improvements in Anglo-Irish relations. In a remarkably short space of time, what had been shaping up as the usual awards ceremony at Irish Distillers in February 2004, to present the gongs for 2003 including Sailor of the Year, had been re-shaped as a Royal occasion, while retaining the basics of the proven annual ceremony to provide an event in which everyone could feel at ease.

Back in February 2004, Irish sailing was given the Royal treatment in Dublin

For that’s what happened. It all went as smooth as clockwork. Deirdre Farrell was in her element keeping it all nicely but gently under control, while Paddy Boyd’s outlining of Royal protoocal beforehand, and his smooth running of the on-stage happenings, would have made you think he had a second life as some sort of big cheese in the United Nations.

As our double-page spread from the March 2004 Afloat suggests, just about everyone was there, they all had their chance of a word or two – and sometimes many – with the Royal President of the RYA, and then we had to canter through a multiplicity of awards with more appropriate words on stage at each juncture, followed by the presentation of the top trophy, which for 2003 was a double, as it was for Noel Butler and Stephen Campion, new World Champions of the International Laser 2 Class.

The RUYC clubhouse was built in 18 months in 1898-1899

The Princess Royal’s visit this past week to the Royal Ulster clubhouse in Bangor was a very different affair, as she was honouring the clubhouse as much as the club and the history to which it is home. In fact, the RUYC carries so much history that you’d wonder they aren’t burdened with it. But they wear their sometimes colourful past remarkable past lightly, for the creation in Bangor, over an ongoing process since 1984, of one of Ireland’s largest marinas, with all amenities including a boatyard, has meant that Belfast Lough and in particular Bangor sailing can move confidently through the present and on into the future, as dinghy sailors’ needs are superbly met by Ballyholme Yacht Club on the most easterly of Bangor’s notable bays.

This means that while today’s Bangor sailors can see the two clubs of RUYC and BYC as the natural focal points which meet their contemporary social needs, in the case of the RUYC clubhouse, it can double as a really remarkable sailing museum. Among other things, it includes the Lipton Room, filled with fascinating memorabilia of the hyper-energetic millionaire Thomas Lipton, who made no less than five challenges for the America’s Cup through the RUYC between 1899 and 1930.

The eternal challenger – Thomas Lipton campaigned for the America;s Cup five times through the RUYC between 1899 and 1930

For the Royal sailing visitor, study time in the Lipton Room provided a vivid insight into one aspect of RUYC history. But then, after the meeting and greeting session with a diversity of members including RUYC Archivist Gordon Finlay and RUYC Historian Ed Wheeler, who are battling with a mountain of incredible material, the visit to the club was rounded out by the presentation to the Princess Royal by Vice Commodore Myles Lindsay of a legendary cruising book which she assured everyone will be going straight into the bookshelf aboard Ballochbuie.

RUYC Historian Ed Wheeler with his wife Jan in a lighter moment with the Royal visitor

The immediately-cherished book was Letters from High Latitudes, published in 1856 as an account of the voyage by Lord Dufferin (his family seat is Clandeboye near Bangor) to Iceland, Jan Mayen and Spitzbergen in the schooner Foam. It has long been a classic of cruising literature, and it still reads today as crisply as though it was written only last week. For Frederick Temple-Hamilton-Blackwood (1826-1902), who eventually became the Marquess of Dufferin & Ava, was a very able sailor and navigator in addition to being a noted diplomat and imperial administrator and excellent raconteur..

So when a few Belfast Lough sailors got together to form the Ulster Yacht Club in 1866, naturally they asked the local national sailing celebrity, this special man who had voyaged to Iceland and beyond ten years earlier, to become its first Commodore, and he in turn ensured that the new club of which he was senior officer became the Royal Ulster YC in 1869.

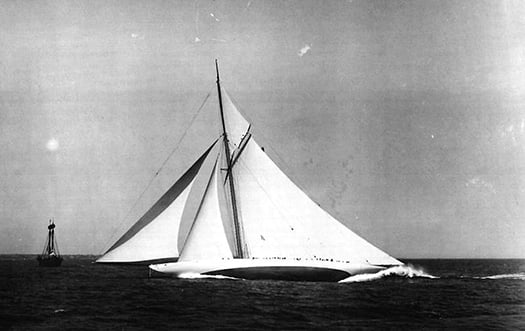

Lord Dufferin’s Foam, which he sailed to the High Arctic in 1856. He was Commodore RUYC 1866 to 1902.

At first they did without a clubhouse as the sought to serve all the more significant sailors throughout the north of Ireland. But by 1872 they rented some premises on Bangor seafront, and then in 1876 they took a lease on a substantial if semi-detached house on an eminence above the eastern side of Bangor Bay.

By the late 1880s and early 1890s, sailing in Belfast Lough was beginning to take off with local confidence, for before that leading northern sailors such as Henry Crawford with the cruiser-racing yawl Nixie, and John Mullholland - later Lord Dunleath - with the schooner Egeria, had tended to cut a dash elsewhere, Crawford on Dublin Bay, and Mulholland also on Dublin Bay, but even more so in the Solent.

However, by 1890, things were changing very rapidly to bring Belfast and Belfast Lough to the forefront of sailing, and this year’s 150th Celebrations at both Carrickfergus and Bangor – the official title is “Sesquicentennial”, since you ask – make us want to know more.

We’re going through such a plethora of major anniversaries these days – both national and international – that it’s natural there should be growing public interest in the story behind the story, the in-depth background to the history. We now want to know more about some great event way beyond the fact that it merely happened at a certain date, and that by doing so it had some significant outcome.

The much-travelled and very successful racing schooner Egeria was built in 1865 for John Mulholland. The following year, he became the first Vice Commodore of Royal Ulster YC

It may well be that one of the reasons sailing is a sport which is lacking in general public resonance is because histories of sailing have tended to concentrate on the narrow narrative of the development of the sport, and the boats it inspires. As for information on the sport’s administrative history, this tends to be no more than closely focused accounts of how clubs and national organisations emerged to meet the growing demands of this new recreational activity, without setting such developments in a broader framework.

Of course, there are many people who go sailing simply to “get away from it all”, for it’s an activity so different from shore life that the mere fact of being on a boat which is sailing is to be conveyed into another world. Such people may well prefer that the history of their beloved escapist sport is kept aloof from the socioeconomic circumstances in which it exists, and the context in which it developed.

But for others, it enriches our experience of sailing to know how it came to be as it is today, and this year in Northern Ireland there are sailing events and commemorations taking place which, when their back-story is analysed in some depth, give us a much better understanding of the way we live today, and how we go afloat today, and it is in turn all set in a meaningful way in the context of the general historical narrative.

In the case of Belfast in 1890, it was suddenly becoming the Mumbai of its day. It may have been the most air-polluted industrial city in the world, but my word they didn’t linger when doing things, as they had the world’s biggest shipyard, the world’s biggest engineering works, the world’s biggest ropeworks, and the world’s biggest linen mills.

It was the sort of place where a bright and energetic young man with some innovative idea in manufacture could make a fortune well within ten years. Indeed, if you weren’t clearly cutting the mustard within two to three years, it was thought you weren’t really in competition at all.

Yet all this was happening in a rapidly-expanding place which had only been accorded city status as recently as 1886, and its famous new-Classical City Hall, the building which still best symbolizes Belfast’s self-image today, was not completed until 1906.

However, all this growth and wealth-creation was taking place in a city which was dominated by the Presbyterian ethos, which had in effect become the northern “state religion” after the Anglican Church of Ireland was disestablished in 1869.

This meant that while there was wealth about, extravagant expenditure on personal enjoyment was frowned upon, and this extended to sailing as to most other things. But the rapidly-rising Belfast area’s middle classes soon found a way of minimizing expenditure while maximizing their yachts sizes and sailing sport.

Some time in 1895, the Belfast Lough One Design Association came into being. Its membership was open to members of any of the half dozen or so clubs now dotted around the lough including the RUYC itself, and its objective was the simple one of creating economical yet effective one design keelboat classes suitable for the sometimes quite demanding conditions to be found in Belfast Lough.

The pioneers of the BLODA persuaded the great Scottish designer William Fife to create them a sweet but able little 15ftLWL keelboat, just 23ft LOA, for 1896, when the first three were racing. And by that time, the Association had become much more clearly structured, as its Honorary Secretary was one James Craig Jnr, aged only 25 but already noted as a formidable organiser.

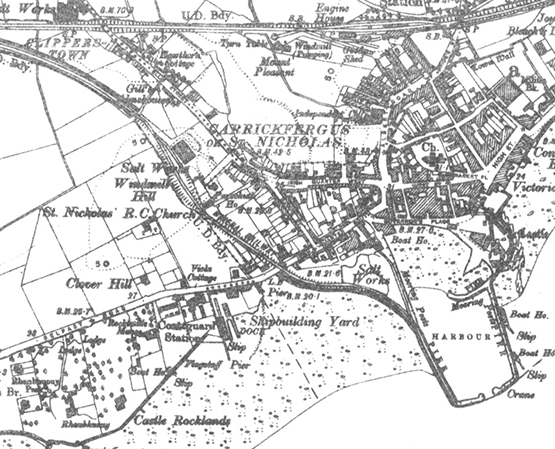

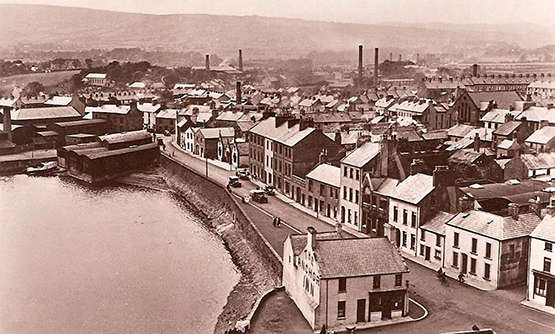

Carrickfergus around 1901. John Hilditch’s first boatyard in 1889 was in the inner harbour where it says “Boat Shed”, then in 1902 he moved to the former shipyard of Paul Rodgers immediately west of the harbour. At the time, Carrickfergus Amateur Rowing & Sailng Club (founded 1866) was in premises on the east side of the East Pier, the more northerly of the two Boat Houses.

In later life he would become Lord Craigavon, first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland in 1921. But in 1896 his prime interest was in expanding the 15ft LWL class with an up-and-coming new boatbuilder, John Hilditch of Carrickfergus. Hilditch was very much in Craig’s sights as the approved builder, as he and his men had already shown with the building of the 35ft G L Watson-designed cutter Peggy Bawn in 1894 that he could stick rigidly to the designer’s drawings, whereas Paddy McKeown, the back-street boatbuilder in Belfast who built the first three 15ft LWL boats, was notorious for always trying to improve on the designer’s original ideas.

The true pioneers. The Fife-designed 15ft Belfast Lough ODs of 1896 showed the way for the 25ft LWL Class I boats in 1897.

But in the fast-moving world of Belfast in the mid-1890s. events overtook them. Several of the more affluent Belfast Lough yachtsmen had already noted with approval the able seagoing power and attractive performance of the first three 15ft LWL boats. In effect, Belfast Lough provided them with a perfect test tank, and the 15ft LWL boats were their “test models”. In a very short space of time, the heavy hitters in the BLODA had persuaded the Association to order the plans of a 37.5ft LOA, 25ft LWL boats, and thanks to the efficiency of the Hilditch Yachtyard – which in those days was only a few sheds at the head of Carrickfergus Harbour - the first eight boats of the BLOD Class I were racing. They made a huge impact in a visit to the Firth of Clyde in 1897, they went to Dublin Bay where they inspired the creation the following year of the DBSC 25ft OD, and even though at season’s end, when the weekly magazine Yachting World - in reviewing their success - described them as “a cheap knockabout class”, a laudatory report in the influential New York Times of their doings at Clyde Fortnight in Scotland was to carry them through with fresh confidence into their greatest year, 1898.

The humble birthplace. The new BLOD Class I boats were built with remarkable efficiency by John Hlditch and his team in the little boatyard in those black sheds on the inner corner of Carrickcfergus Harbour in the wintyer of 1896-97.

In all their glory. The BLOD Class I boats racing in full strength in 1898.

But anyone who is into Centenaries will realise that Belfast in 1898 had become a very different place from Belfast in 1798. In 1798, Belfast had been a hotbed of the United Irishmen, and one of the local leaders in The Rising, the Presbyterian Henry Joy McCracken, had been hanged with The Rising’s suppression, executed in the town centre on public land which had been donated to the citizens of Belfast by his own grandfather.

In addition to his many other interests, McCracken had been a very early pioneer in developing Belfast Lough sailing, and he and his friends cruised most summers to the west coast of Scotland. But while McCracken may have been taken, his friends lived on in an increasingly different Belfast in the early 1800s, where successful trade and manufacturing industry obliterated any earlier political idealism. Nevertheless some of those former shipmates of Henry Joy McCracken formed the Northern Yacht Club on Belfast Lough in 1820. But as Belfast port became ever more industrialised, they found it more congenial to sail on the Firth of Clyde, within a few years there was a Scottish branch, and by 1838 the Royal Northern Yacht Club of Rothesay had completely absorbed its Belfast unit, and there wasn’t to be another yacht club on Belfast Lough until Holywood yacht Club came into being beside its drying anchorage at the little County Down town immediately east of Belfast in 1862.

By the end of the 1860s, the Holywood club had been joined by the clubs at Carrickfergus and the Royal Ulster, but some years were to pass before the sport of sailing came central stage. Yet by 1898, Belfast Lough sailing wasn’t just centre stage on Befast Lough. It was world-leading. The Fife-designed One Design classes were widely admired at a time when Fife’s star was very much in the ascendant, and then in August 1898, Thomas Lipton announced his first challenge for the America’s Cup through RUYC, the actual contest to take place in New York harbour early in October 1899.

Already, there was a movement among members to build a proper trophy clubhouse for the RUYC, and Lipton made it clear he was unenthusiastic about having his challenge based on a club which was head-quartered in a semi-detached suburban house. But James Craig had a talented older brother who was an architect, Vincent Craig, and he soon had the plans drawn up for an arts & craft building which continues to dominate the Bangor waterfront today, and houses a priceless collection of yachting memorabilia, while at the same providing a convivial venue to celebrate an important Sesquicentennal.

Thomas Lipton’s Shamrock IV of 1914 was one of his most promising challengers. But the outbreak of the Great War signalled the end of the Golden Era, and though Shamrock IV finally challenged unsuccessfuly in 1920, in was in very subdued circumstances.

Today, we know that none of Lipton’s Americas Cup campaigns succeeded, though some came tantalisingly close to success. Today, we know that John Hilditch’s wonderful boatyard only lasted for 24 years, and the poor man, worn down by overwork and finacial stress, died on Christmas Eve 1913. And today we know that, regardless of the turmoil within Ireland from 1912 to 1922, it was the Great War of 1914-1918 which was to wipe out the cream of an entire generation from the north of Ireland, with sports like sailing taking a very long time to recover, if they ever really did recover until much more modern times.

Yet in 1898, it was a time of such hope, such anticipation, such planning – such excitement and exuberance. It can all be captured again with the many events at Royal Ulster and Carrickfergus this summer, when in addition to the clubs’ 150th anniversaries, they’re also staging a Hilditch Regatta at Carrickfergus with a Parade of Sail to Bangor to give proper prominence to the memory of a man who contributed so much to the success of Belfast Lough sailing in the Golden Era of 1894 to 1914.

Royal Ulster Yacht Club Celebrates 150 Years of Sailing

In 2016, Royal Ulster Yacht Club is celebrating the 150th Anniversary of its formation in 1866. To mark the anniversary there will be a series of sailing and cruising events throughout the summer.

The important date was highlighted by WM Nixon last Saturday in his Afloat blog Belfast Lough Celebrates 150 Years of Organised Sailing in Style

The main focus of the year’s celebrations is around the end of June starting with the UK and Ireland National Championships of the Sigma 33 Class of yachts (17th-19th June). This event will attract sailors from around Ireland, Scotland, Isle of Man and North West England and Wales.

The following weekend the Club is running its Annual Regatta along with a Keelboat Weekend Event. The Annual Regatta is the flagship event in the club’s year and this year it will include visiting boats from Scotland, Dublin Bay and Strangford Lough to race alongside the competitors from the other yacht clubs in Belfast Lough. The day will start with a Sail Past in front of the Clubhouse and a naval Guardship will be in attendance. The visiting boats will include modern racing craft and classic boats such as the River and Glen classes from Strangford Lough some of which started life competing at Royal Ulster YC over 90 years ago. We are also expecting that several of the classic Howth 17 classes will travel north for our event.

The cruising fleet will be joining forces with similar associations such as the Irish Cruising Club and the Clyde Cruising Club for a social gathering before a cruise-in-company to Scottish waters.

The social highlight of the celebrations will be a Black Tie Gala Dinner at the Club on 1st July.

Historic Belfast Lough Boatyard Lives On Through Classic Yachts

The recreational marine industry is a demanding trade. Your customers buy boats for pleasure, so they assume it’s a fun business to work in. Thus there’s no lack of potential boat designers and builders to be found among the children of those who only sail for sport and fun, for they see that the adults enjoy being around boats, and they get to think that being around boats all the time for work and play is the only way to live.

But in the end, business is business. The bottom line rules everything else. However enthusiastic young people may have been when first going into the boat trade, as they battle on with running their own marine business they find the world of commerce can become a cruel place. W M Nixon considers the challenges of boat-building, and looks at the story of John Hilditch of Carrickfergus, who was one of the brightest stars of the Irish boat-building industry in the golden age of yachting, yet his light was extinguished after barely two decades.

The name of Hilditch of Carrickfergus is synonymous with classic yachts of significant age. John Hilditch built the 36ft G L Watson-designed cutter Peggy Bawn in 1894, and she still sails. In fact, she sails in better shape than ever, as she had a meticulous restoration completed for Hal Sisk of Dun Laoghaire in 2005.

More recently, in 2013 the Hilditch-built Mylne-designed Belfast Lough Island Class 39ft yawl Trasnagh was restored for Ian Terblanche in Devon in time for her Centenary. And in 2015, the Belfast Lough OD Class I Tern – 37.5ft LOA to a William Fife design and built in 1897 with seven sister-ships by John Hilditch - has appeared in Mallorca so superbly restored that when she went on to Les Voiles de St Tropez at the end of September, she won her class despite it being heavy weather, and she only just out of the box.

Peggy Bawn in her first season afloat in 1894. She was built for A J A Lepper, Commodore of Carrickfergus Sailing Club, who was one of John Hilditch’s most loyal clients. Photo courtesy RUYC

Peggy Bawn in her first season afloat in 1894. She was built for A J A Lepper, Commodore of Carrickfergus Sailing Club, who was one of John Hilditch’s most loyal clients. Photo courtesy RUYC

A monumental achievement. All the boats of the new Fife-designed Belfast Lough OD Class 1 of 1897 were built by John Hilditch in less than a year. Photo: Courtesy RUYC

But we don’t have to go to distant restoration specialists to find evidence of the large and varied Hilditch output. The first five boats of the Howth 17 OD class were built by John Hilditch immediately after he’d built the eight Belfast Lough Class I boats. The little new Howth gaff sloops – rigged with huge jackyard topsails as they still are today - sailed the 90 miles home down the Irish Sea to Howth in April 1898, and had their first race on May 4th 1898. All five of the original Hilditch creations continue to race with the thriving Howth 17 class, which today has eighteen boats.

The Howth 17s Aura (left) and Pauline. Aura is one of the original five Howth 17s built for 1898 by John Hilditch immediately after he had completed the Belfast Lough Class I boats. Photo: John Deane

This concentration of yacht design development in a short time span, and through just one boatyard, is rare but not unique – the great name of Charlie Sibbick of Cowes shone equally briefly but even more brightly at much the same time, as he was a designer too. But Sibbick made his name in an established international centre for sailing. Yet when John Hilditch – who was both a seafarer and a fully-qualified shipwright – established his yard at Carrickfergus on Belfast Lough in the winter of 1892-93, the north of Ireland was still a relative backwater in international sailing terms. Thus his achievement is indeed remarkable. For by the time Hilditch closed down in the winter of 1913-14, he had put Belfast Lough firmly in the global picture as a pace-setter in yacht development, and his pivotal role in that transformation is gaining increasing recognition.

Not that there hadn’t been sailing in Belfast Lough before Hilditch came along. There are many yacht and sailing clubs around this fine stretch of sailing water, and the most senior of them is Holywood Yacht Club (on the waterfront below the hills where Rory McIlroy learned to pay golf), which dates back to 1862. And in 1866, two more new clubs came into being – Carrickfergus Sailing Club which was obviously location-specific, and the Ulster Yacht Cub, which became the Royal Ulster Yacht Club in 1869, but was a premises-free moveable feast until 1898, when America’s Cup challenger Thomas Lipton insisted it have a clubhouse, which was duly opened on an eminence close above the Bangor waterfront in April 1899.

The shared foundation year which goes back through the mists of time to 1866 means that both clubs will be celebrating their 150th Anniversaries in 2016. They’ve been quietly working on their separate plans towards celebrating this significant date, with a massive new history of the RUYC under way for a couple of years now and due for publication in the Spring, while Carrickfergus also has plans in the publication line.

Yet although there is much to write about now, in both club’s cases the pace of development was relatively slow until the late 1880s, for until that time, the business of the rapidly expanding city of Belfast was business, and more business. It wasn’t until the 1880s that leisure sailing began to get serious attention from the rapidly growing middle classes of the greater Belfast area. But once they did begin to take it up, they did so with complete enthusiasm, and the sailing pace of Belfast Lough during the 1890s, and on towards 1910, had few rivals.

For the rapid yacht design development seen during John Hilditch’s busy years, compare this with the next image. The old-style hull of Peggy Bawn is revealed as she is lifted out of the Coal Harbour Yard in Dun Laoghaire in 1996 for a first attempt at restoration. Later, Hal Sisk took over the project, and it was completed for him by Michael Kennedy of Dunmore East. Photo:W M Nixon

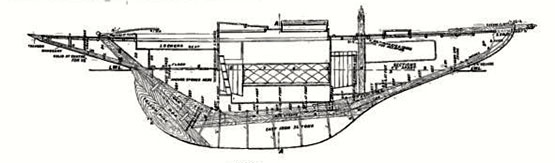

The new style shape. Although they were built only three years after Peggy Bawn, the Fife-designed Belfast Lough Class I boats had a much more modern hull shape and were primarily racing boats, yet they were required to be well capable of sailing to Scotland and Dublin Bay, and did so

The new style shape. Although they were built only three years after Peggy Bawn, the Fife-designed Belfast Lough Class I boats had a much more modern hull shape and were primarily racing boats, yet they were required to be well capable of sailing to Scotland and Dublin Bay, and did so

Formidable performers. The Belfast Lough Class I boats Merle (6, Brice Smyth) and Flamingo (2, John Pirrie) racing hard in 1898. Both owner-skippers were members of Carrickfergus SC, and based their boats there. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

Formidable performers. The Belfast Lough Class I boats Merle (6, Brice Smyth) and Flamingo (2, John Pirrie) racing hard in 1898. Both owner-skippers were members of Carrickfergus SC, and based their boats there. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

In order to meet this demand, John Hilditch was able to expand his new boatyard at an extraordinary pace. Even then, he couldn’t keep up with demand, such that one new Belfast Lough class, the Linton Hope-designed lifting-keel 17ft LWL Jewel Class of 1898, had to be built in Chester in England. And at the same time, the fishing-boat builder James Kelly of Portrush on the North Coast found that yacht-building to supply the new craze was much more lucrative than producing his own variant of the classic Greencastle yawl for fishermen on both the Irish and Scottish coasts, and he went into yacht-building both for Belfast Lough and Dublin Bay.

But in terms of overall contribution to the transformation of Belfast Lough sailing, John Hilditch was very much in a league of his own. So much so, in fact, that noted international classic sailing polymath Iain McAllister got to thinking last winter that even though no trace whatsoever now remains of this once famous yard, it was time and more for John Hilditch’s work to be celebrated, and how better than a Hilditch Regatta during 2016 to tie in with other Belfast Lough sailing celebrations?

It’s a great idea which seemed almost too good to be true. But thanks to quiet work behind the scenes, most notably by Wendy Grant who recently became Commodore of Carrickfergus Sailing Club neatly in time to hold the top post during the 150th celebrations (she’s the mother of renowned offshore navigator Ian Moore), plus a special sub-committee in RUYC which likewise holds to the notion that the early stages of good work are best done by stealth, a programme is emerging which will keep all organising parties happy while providing participants with a manageable user-friendly schedule.

It has all become viable during this past week thanks to the confirmation that the more distantly-located significant classic boats of the Hilditch oeuvre – Peggy Bawn of 1894, Tern of the 1897 Belfast Lough Class I, the Howth 17s of 1898, and Trasnagh, the Island Class yawl of 1913 – all hope to be in Belfast Lough towards the end of June 2016, where numbers will be further swollen by the Hilditch-built Royal North of Ireland YC Fairy Class of 1902, together with some of their sister-ships from Lough Erne.

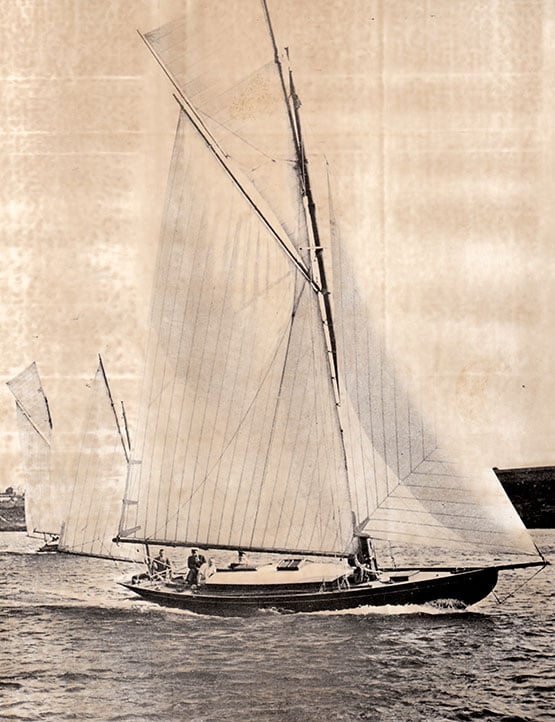

The Hilditch-built Tern in a breeze of wind on Belfast Lough, 1898

Tern in a breeze of wind at St Tropez, September 2015.

In addition, the fleet will be increased by other classics of every type, coming together to wish the Hilditch boats well at this special time. And there’ll be a goodly contingent of Irish Sea Old Gaffers which will be heading towards the big event on Belfast Lough in late June by way of the Old Gaffers Rally at Portaferry in the entrance to Strangford Lough from June 17th to 19th.

But before getting carried away by anticipation of all this festivity, let us remember that this week’s thoughts were introduced by a precautionary reminder that the boat-building trade is no bed of roses. So just what did go wrong, that the much-admired Hilditch yard faced closure before the end of 1913, with the man himself dead – perhaps broken-hearted – before the end of 1914?

There seem to be a number of explanations, all of which combine to explain the sudden demise of a great enterprise. The incredible rate of economic expansion in Belfast – which had been accelerating virtually every year since around 1850 – seems to have first shown significant signs of slackening in 1910. The greater Belfast economy did continue to expand in the broadest sense, but the rate of expansion was now slowing.

During the rapid growth years, John Hilditch was able to meet demand, but regardless of the underlying economic patterns, by 1910 his market was beginning to reach saturation levels. If people had continued to change their boats every three years or so – as they’d anticipated doing when the Belfast Lough One Design Association was established in 1896 – then an artificial demand might have been maintained. But people were beginning to realise that a good one design boat was good for much longer than a mere three years. In fact, some argued that a class was only bedded in after three years. So the number of new boats being ordered dried to a trickle.

Yet those boats that were being ordered became individually larger. When the Alfred Mylne-designed 39ft Belfast Lough Island Class yawls began to be conceptualised as the world’s first true cruiser-racer one designs in 1910, they would be far and away the biggest and most expensive one designs Hilditch had yet built. He held out for a price of £350 per boat, but the potential owners – hard-headed Belfast businessmen determined to drive a tough bargain and not to be seen to weaken – wouldn’t budge beyond £345.

In those days, yacht-building was simply priced by overall length, so Hilditch resigned himself to accepting the £345 by agreeing to build a boat with a slightly shorter bow. For all parties, it was a case of cutting off one’s nose off to spite one’s face. The new Island Class yawls were handsome enough. But with a longer bow, they’d have been beautiful.

The island Class yawl Trasnagh, seen here in her first season of 1913, is believed to be the last boat to have been built by John Hilditch. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

The island Class yawl Trasnagh, seen here in her first season of 1913, is believed to be the last boat to have been built by John Hilditch. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

The last of them, Trasnagh herself in 1913, was the last boat to come out of a formerly great yard rapidly tumbling towards extinction. The times were restless politically as well as economically, so it wasn’t a good time to rely on building pleasure boat for a living. And apart from the saturation of the market and the financial demands of building the relatively large Island Class boats, sailing was no longer attracting the same number of newcomers, as rival interests such as motor cars and aeroplanes were taking away many potential enthusiasts,

Yet ironically, had John Hilditch been able to hang on for just another year into the beginning of the Great War of 1914-18, a slew of war work for the Admiralty would have given his yard a new lease of life. But it was not to be. The yard was gone. And soon, so too was the man himself.

But the boats live on. One hundred and two years after John Hilditch’s death, boats that he created are still sailing the seas, and their assembly in Belfast Lough from June 22nd 2016 onwards will be a reminder that, once upon a time, on a site long since covered by Carrickfergus’s re-developed waterfront, John Hilditch and his team built nearly a hundred fine yachts, the best of which have well stood the test of time. All that together with the 150th Anniversaries of two remarkable sailing clubs. For sure, late June on Belfast Lough is going to be one very special time.

Trasnagh restored for her Centenary in 2013

Restored 1897 Belfast Lough OD Tern Makes Successful Debut At Les Voiles De St Tropez 2015

The 1897-built Fife-designed 37ft Belfast Lough One Design Tern has made a successful debut in the classics scene in the Mediterranean by winning her class in Les Voiles de St Tropez 2015 writes W M Nixon.

We’ve reported from time to time on the Mallorca-based restoration project on Tern on Afloat.ie over the past 18 months. But we were keeping our fingers crossed that all would continue to go well after her successful launching on August 6th - so much effort was going into the final work and detailed finishing that, with time limited before she could be taken to the major regattas in the south of France, all and any sorts of hitches could still occur.

Since then, there has been further concern with the weather in southeast France being exceptionally bad, with seriously adverse effects in recent days on the classic events in both Cannes and St Tropez. But Tern has not only come through unscathed, she has won her class overall despite the fact that there was only racing on two days at St Tropez, recording a first and second.

This has all been hugely confidence-building for the team involved, and greatly improves the likelihood of Tern coming to Ireland next year. The Royal Ulster Yacht Club on Belfast Lough – which was her home club in her early days and still displays several photos of Tern and her six pioneering sisters from 1897 and 1898 - is celebrating its 150th Anniversary in 2016, while at different times Tern was also based in Cork Harbour, Waterford and Dun Laoghaire, and she was one of the five yachts taking part in the Founding Cruise of the Irish Cruising Club to Glengarriff in July 1929, giving Tern direct links with all of the Irish coast between West Cork and County Antrim, as she was built by Hilditch in Carrickfergus.

Aboard Tern on her first sail since restoration, off the coast of Mallorca in August

When the new Belfast Lough ODs started racing in May 1897, it all happened so quickly that when sailmakers Ratsey & Lapthorne at their Scottish loft found that they lacked Tern’s allocated sail number 7, shortage of time meant they simply used an inverted 2 instead, and this has been faithfully replicated in the new 2015 sails, also made by Ratsey & Lapthorne.

When the new Belfast Lough ODs started racing in May 1897, it all happened so quickly that when sailmakers Ratsey & Lapthorne at their Scottish loft found that they lacked Tern’s allocated sail number 7, shortage of time meant they simply used an inverted 2 instead, and this has been faithfully replicated in the new 2015 sails, also made by Ratsey & Lapthorne.

As well, the hull lines of the BLOD 25s from 1897 were then used for the building of the Dublin Bay 25s from 1898 onwards, though the Dublin Bay boats had a higher specification, and carried a lead ballast keel instead of the Belfast Lough boats’ less expensive cast iron.

One of the famous William Maguire Dublin Bay models in the National Yacht Club is of the Fife-designed Dublin Bay 25ft OD, whose hull lines were identical to Tern. And Tern herself - though by that time rigged as a cruising yawl - was based at the National YC from 1944 to 1954, firstly under the joint ownership of Charles E Hogg and Maurice Healy from 1944 to 1949, and then under the ownership of J J Lenihan until 1954, after which she moved to Falmouth in southwest England. Photo: W M Nixon

Montrose wins Waverley Cup at Belfast Lough Autumn Keelboat Series

Another beautiful morning's race saw the half-way stage of the Belfast Lough Autumn Keelboat Series and the end of the Waverley series. The 18 boat fleet have enjoyed 3 very enjoyable races so far in gorgeous sunshine, wondering why the rest of the summer wasn't the same. We can only hope that October fares similar.

Tradtional tight racing in the 110 year old Waverley class has seen all of the boats win one race. John McCrea's Ivanhoe won the final one but any hopes of winning the series overall were dashed when the husbacnd and wife team of Robin "Sailor" and Victoria Millar folowed them home in front of Ben Gouk's Fair Maid, winning the series by a single point.

In the IRC fleet, Phil Davie's Giggle took advantage of the absence of Indigo to take the lead in the series overall with 2 wins from Richard and Pauline Donnan's 1. John Minnis and B Roche are enjoying their first few races in their new Final Call but finding it hard to stay close enough to the bigger yachts.

In the Sigma's, Sqwawk struggled with the lack of their leader Paul Prentice and a depleted team on duty at the RYANI Youth Nationals and elsewhere. Even in relatively light winds, Johnny Henry struggled to keep the boat upright enough with only 2 on the rail, and Starshine Challenger took advantage to score their first win of the series. Special mention must be made of Burton Allen (and Adrian Allen) who was absent due to attending the wedding of his grandson Michael.

The NIRKRA fleet have also seen different winners in each race and this week was the time for Garth and Myles Lindsay's Johnathon Star to maximise the advantage from their bigger sail plan to lead by 90 seconds over the water from Jim Coffey and Tom Bell's QtPi with David Milne's Manzanita just behind. Last week's winner Chatterbox was 5th on corrected time struggling in the lighter winds in Race 2 and 3 having ran Manzanita close in Race 1, coming 2nd in that race only 3 seconds behind on corrected time. Alan Morrison's Starflash has struggled so far this series on handicap, possibly due to success earlier in the year when they were setting the benchmark. Only 5 minutes on the water separated the 6 boat fleet in the first two races showing the competitive nature of this restricted class. After 3 races, Johnathon Star leads from Manzanita and Chatterbox by 2 points.

The whitesail NHC fleet have also enjoyed changing fortunes and having won the first two races and leading the series overall, John Ritchie's Mingulay saw D Lowe's Gecko cling on close enough to the quicker boats last Sunday to clinch the race on handicap although the results posted look a bit irregular and may need reviewed. John Moorehead's Margarita was 2nd and lies 3rd overall behind Messrs Curry, Wilde and Nixey in Enigma in 2nd place.

Many thanks must go to Colin Loeonard who has set great courses over the first 3 races. We now look forward to Elaine Tyalor who will take over for the remaining 4 races running until 25th Oct

October.

IRC Fleet

1st Giggle RUYC Phil Davis

2nd Indigo RUYC R & P Donnan

3rd Final Call RUYC J Minnis/ B Roche

SIGMA Fleet

1st Squawk BYC/RUYC P Prentice

2nd Starshine Challenger BYC/RUYC B Allen

3rd Cariad BYC/RUYC G Bell

NHC Fleet

1st Mingulay RUYC J & M Ritchie

2nd Enigma BYC/RUYC Messrs Curry/Wilde/Nixey

3rd Margarita RUYC J Moorehead

NIRKRA Fleet

1st Jonathan Star RUYC G Lyndsay

2nd Manzanita BYC/RUYC D Milne

3rd Chatterbox RUYC/BYC D Quinn

WAVERLEY Fleet

1st Montrose RUYC/BYC R & V Millar

2nd Ivanhoe BYC/RUYC J McCrea

3rd Fair Maid BYC B Gouk

Did The America's Cup Destroy Belfast Lough Sailing?

#americascup – The 35th America's Cup series will be staged in Bermuda in 2017, and already the first team – Ben Ainslie Racing – is starting to settle into its base in the islands at the beginning of a developing process which, it is hoped by locals, will contribute significantly and sustainably to an economy which is by no means as prosperous as the popular image of Bermuda would suggest.

Yet past experience of being involved with the America's Cup circus suggests that while there are definitely immediate and highly visible benefits, they're ephemeral and are more than offset by a hidden but very definite downside. And the pace of the event at its peak is at such a level that almost immediately afterwards there's a sense of anti-climax and recrimination which can poison a sailing centre's atmosphere for years. W M Nixon considers how sailing's most stellar event affected Irish sailing, looks at a more recent continuation of this story, and then takes up the tale of an old boat whose class's health suffered collateral damage from America's Cup fallout.

It was while tracing the story of Tern, a 37ft William Fife-designed Belfast Lough One Design built by John Hilditch of Carrickfergus in 1897, that we stumbled into what is arguably an example of the America's Cup having a seriously damaging effect on local sailing.

Somehow or other, Tern has survived, and is currently being restored to international standards in Palma, Mallorca. But it was when a couple involved with her restoration came to Ireland shortly after Christmas to spend some time researching her history that we had to face the fact that while Belfast Lough's involvement with the America's Cup is seen as a glamorous and still-celebrated era, as far as everyday sailing is concerned it did little but harm.

The context is intriguing. Belfast in 1897 was the Mumbai of its day. From a population of around 80,000 in 1850, by 1910 its unprecedented expansion through massive industrial innovation and development, built largely around ship-building and linen manufacturing, had seen numbers soar towards 300,000. The city was a byword for pollution, over-crowding, and ill health, but equally it was noted as a place where anyone with energy and an innovative manufacturing idea was expected to have made their fortune within ten years, and around three or four years to start reaching towards wealth was seen as a not unreasonable aim.

In such a frenetic and ambitious atmosphere, sailing on Belfast Lough developed apace, and it developed ambitiously and competitively for all that the lough, while providing splendid sailing water, lacked any really good natural anchorages. New boats and new boat types appeared with bewildering rapidity, and a sort of one design keelboat concept was being accepted by the early 1890s in order to make good racing accessible to keen young men at a reasonable price. There may have been much underlying wealth about, but spending it on extravagances like large and expensive yachts was frowned upon.

By 1896 a young whiskey distiller called James Craig (he later became Lord Craigavon) was promoting the idea of a strict One Design keelboat around 23ft LOA, and about 16ft LWL, designed by the great William Fife in Scotland, but built on the lough by John Hilditch at his Carrickfergus boatyard. As the pioneer of the concept in the locality, Craig called the new class the Belfast Lough No. 1 OD, but the first boat to the design, his own Fugitive, was barely finished before the One Design keelboat ideal was taken up with enthusiasm by another group which decided they wanted something to the same concept, but much larger.

These new boats, the first of which were rapidly built in time for the 1897 season, were almost exactly enlarged versions of Fugitive, but were all of 37ft overall and 25ft waterline. In a case of Might is Right, the bigger boats now became the Belfast Lough Number Ones, while Fugitive and her sisters were demoted to Number 2, and by the early 1900s they'd slipped still further to become the Number 3s when yet another class appeared, this time around 31ft LOA.

There were enough of the new 37ft Number Ones afloat to make a real impact on Clyde Fortnight in 1898, and as they were well able to sail across Channel to do so, they were arguably the world's first offshore one design. The previous year, some had visited Dublin Bay, where they so impressed the locals that they were the inspiration for the Dublin Bay 25s, to the same lines but built to a higher specification and with lead ballast keels, rather than the Belfast Lough boats' cast iron keels.

Whimbrel on the Clyde in 1898. They'd the potential to be the world's first offshore one design, but offshore racing hadn't yet been invented. Whimbrel is currently undergoing restoration in Bordeaux. Photo courtesy Gordon Finlay/RUYC

By the middle of the 1898 season, the Belfast Lough One Designs were in all their glory, and our header photo from that season shows a class which surely promised at least a decade of great racing. Yet their peak years barely stretched beyond the turn of the century, and within five years they scarcely existed as a class. Well before the Great War broke out in 1914, they were starting to spread near and far in a scattering which was to continue post war and in most cases ended up in their eventual demise. But remarkably, two have survived and both are undergoing restoration, Whimbrel Number 8 in Bordeaux and Tern, number 7, in Mallorca.

Patricia O'Connell and Alan Renwick live in Palma where he is a master craftsman with Ocean Refits while she – a former Honorary Secretary of a Georgian preservation society in Dublin – has undertaken the tracing of Tern's story, as Tern's restoration is Alan's current project. They arrived in Dublin in the dying days of 2014, and by the time they headed back to Palma well into January, they'd spent time in Cork and Northern Ireland following the old boat's elusive trail, and had also called in Howth to see Ian Malcolm's Howth 17 Aura, which was built in Hilditch's yard within a year of the construction of Tern.

Still going strong. The 1898 Hilditch-built Howth 17 Aura off Carrickfergus Castle for her Centenary, April 1998. With her sister-ships, she then sailed the 90 miles home to Howth. Like Tern, she is number 7 – and like Tern, there's an element of confusion with sail number 2. Photo: David Jones

The original five Carrickfergus-built Howth 17s still sail together as part of a thriving class of twenty Howth 17s. But the impressive class of eight Belfast Lough One Designs from the same era have been remembered for more than a hundred years only as photos on the walls of the Royal Ulster Yacht Club. What went wrong?

The America's Cup – that's what went wrong. In the early years of sailing's premier trophy, there was remarkable Irish involvement. After the schooner America won it with a race round the Isle of Wight in 1851, it took a while to establish a format for races to try and wrest it back from the New York Yacht Club in contests in America. During the 1870s, there were three challenges – two from Britain and one from Canada. Then in the 1880s there were three from Britain and one from Canada, the final one from Britain in 1886 being through the Royal Northern YC of Scotland, but that was because the owner's wife was Scottish – the husband was Lt William Henn whose family home was on the north shore of the Shannon Estuary.

But while the Henn family's hefty cutter Galatea was another unsuccessful challenger, at least she was seen in the waters of the Shannon Estuary. Yet although the first two challenges in the 1890s were by racing machines owned by a yachtsman whose ancestral pile was also on Shannonside, neither boat was seen anywhere near Adare Manor, the home of Lord Dunraven on the south side of the Shannon Estuary, whose two campaigns in 1893 and 1895 were unsuccessful and increasingly acrimonious.

With the passage of time, it becomes increasingly clear that Dunraven got a decidedly raw deal. But in the feverish atmosphere of rapid economic expansion in the 1890s, the world was more interested in pushing ahead with new projects rather than putting right old wrongs. Someone who saw the developing publicity and business potential in the America's Cup was Thomas Lipton, the Scottish-born grocery magnate whose American empire was thriving with a combination of his sheer love of hard work, and gift for publicity.

Lipton had noted the extraordinary level of public interest in Lt & Mrs Henn's "family" challenge in 1886 – they'd actually lived on board the Galatea at he time. But much more importantly, he'd noted the international crisis which arose from the Dunraven affair, and cannily realized that anyone who could smooth the waters with a good-tempered America's Cup challenge would attract acres of favourable coverage, regardless of the actual result.

That said, as a highly competitive individual, there's no doubting he was keen to win. But even though all five of his yachts called Shamrock making his America's Cup challenges between 1899 and 1930 were unsuccessful, with some being much more closely fought than others, he remained resolutely good humoured throughout, and expansion of his retail empire continued unabated. But what's less widely known is that while the America's Cup Shamrocks were numbered I to V, there was a sixth Shamrock, an un-numbered 23 Metre, which raced as his private yacht. It's said that when she didn't perform as well as she should have, the old man could be very grumpy indeed.

But that's all in the future. Here we are in the latter half of the 1890s, and on Belfast Lough this wonderful new class of 37-footers is spreading its wings, thriving on the fact that although the owners lived all round the lough and were members of one yacht club, the Royal Ulster YC founded 1866 and given the "Royal" in 1869, they could feel at home wherever their boats happened to be, as the RUYC had no clubhouse. This was a true sailing club, fixed only to good sailing water, and with the Belfast Lough Number Ones they could sail it well.

It was too good to last. Thomas Lipton was a man in a hurry. He knew that he needed a yacht club of international standing through which to make his first America's Cup challenge. But as he was of humble birth and very much in trade instead of benefitting from inherited wealth, there were few yacht clubs open to him. However, his parents had come from Monaghan, not only in Ireland but particularly in Ulster. In the can-do atmosphere of Belfast in the 1890s, it was indicated that the Royal Ulster might be receptive to his interest. He was soon a member, and plans were roaring ahead for an 1899 Challenge with Shamrock I.

But the RUYC had taken a cuckoo into its nest, or rather its virtual nest. It emerged that a virtual nest was not enough for the aspirations of a serious America's Cup challenger, he needed a real nest. Lipton was soon insisting that his America's Cup challenge, now irreversibly under way, would required the RUYC to have a proper clubhouse impressively sited above the waters of Belfast Lough where it was assumed he would very soon be the defender in the America's Cup.

The new RUYC clubhouse was completed at the behest of Thomas Lipton in 1899 after just 18 months work.

And he got his way. An impressive arts and crafts tower-topped clubhouse design was drawn up by James Craig's brother, the architect Vincent Craig, and the new RUYC clubhouse was opened in April 1899, having been built in 18 months flat. Well – not quite flat. They were in such a hurry for completion that there wasn't the time to entirely level the hillside site on the Bangor waterfront where the new clubhouse was built, and even today the ground floor is on two or three different levels.

That said, it's an impressive building to have been put up in such a short time, and somehow they achieved a sort of instant antiquity with it – today it seems much older than its 116 years, and it has always been thus.

But antique or otherwise, it doesn't seem to have been desired by all the members. There were 150 of them, yet only 30 contributed directly to the cost of the new clubhouse. And others took their sailing elsewhere. We live in hope of finding letters or a sailing diary from this period which will tell us what was really going on, for official club committee papers only cover what was on the agenda and recorded in the minutes. Thus even if there was an almighty row going on about the very fact of the somewhat cavalier building of this new clubhouse, at the time it would have been something known to everyone, and talked about by everyone, yet not written down simply because everyone knew of it, and it didn't happen to be directly pertinent to the business of the day. And anyway, once the clubhouse was in being, that was that – the best thing was to get on with living with it.

Yet the fact is that a distinct division arose in sailing along the south coast of Belfast Lough. The conspicuous Royal Ulster YC in Bangor became the public face of yachting in the area. But further up the lough at Cultra beside a roadstead anchorage, what had been a modest canoe club developed in 1899 into an amalgamation of the Ulster Sailing Club with the Cultra Yacht Club to become the North of Ireland Yacht Club, and by 1902 – by which time Lipton had already unsuccessfully challenged twice for the America's Cup through RUYC – the new place at Cultra had become the RNIYC, with a modest clubhouse aimed exclusively at serving its members' sailing needs rather than following grandiose ideas of international yachting campaigns for plutocrats who were only very seldom about the place, if at all.

Inevitably some of the best sailing men in the north were involved with this move to Cultra where many had always anchored their boats in any case, and others had followed. Whether or not the active membership of the RUYC was seriously depleted we can only guess. But the fact is that the relatively small membership of a provincial yacht club had somehow to find, within its membership, the essential people with the necessary talent and experience to provide the back up committee and officer services for Lipton's America's Cup Challenges, with the next one coming along as soon as 1903.

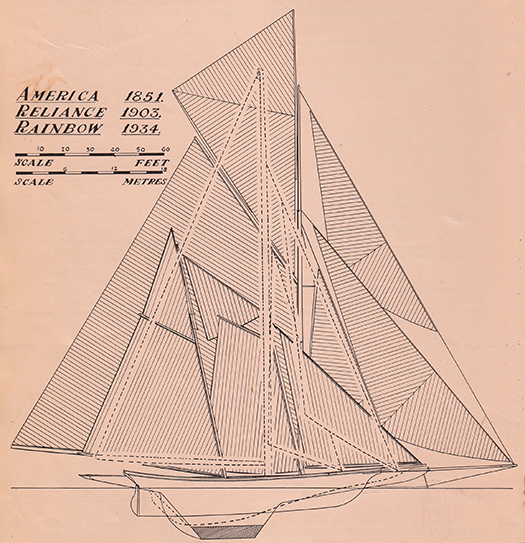

America's Cup design development 1851 to 1930. The Challenge Committee of the RUYC may have come on the scene 48 years after the era of the schooner America, but they still had to cope with the challenges posed by the design development from boats like Reliance in 1903 to the J Class Rainbow in the 1930s.

The drain on RUYC personnel resources was heavy in an era when time-consuming Transatlantic voyages by ship were required for the challenger's committee to meet with the committee of the defending New York Yacht Club. Something just had to give, and it seems to have been the level of personal sailing within RUYC, and particularly with the Number One Class.

The new RNIYC setup at Cultra was establishing its own modest new 22ft OD class, the Linton Hope-designed Fairy Class (also built by Hilditch), so they may well have seen the much larger Number Ones as simply too large, and tainted by the new vulgarity of the RUYC. Whatever the reason, the Belfast Lough Number One Class was a brilliant flame which burned only briefly as a class, even though the boats survived individually with most of them becoming fast cruisers.

But as for the America's Cup, it continued on its melodramatic way, with skulduggery par for the course. After 1903's unsuccessful challenge, when Shamrock III found herself ill-matched against the hyper-giant Reliance, the RUYC committee may have returned home to recuperate and gather strength for Lipton's next campaign. But he was scheming other ideas, and it has been only relatively recently discovered that, unbeknownst to RUYC, he was in preliminary negotiations with the Royal Irish YC on Dublin Bay to organise his fourth challenge.

Lipton and the RUYC thought they'd an impressive boat with the Fife-designed Shamrock III in 1903, but this is what they came up against in America – mega-boat Reliance

From a purely commercial point of view, you can understand his thinking. The formerly despised Irish community in the US was expanding rapidly in numbers and prosperity by 1904. Coming in with a challenge through the Royal Irish Yacht Club would hit more market targets than the narrower appeal of a Royal Ulster challenge. It was crude but shrewd business thinking. But fortunately for goodwill in the sailing community, nothing came of it. Challenge 4 through RUYC was slated for 1914, but with the Great War breaking out it was held off - with the radical and very promising Shamrock IV designed by Charles E Nicholson stored in the US – until 1920, with Shamrock IV defeated by the narrowest margin. And then in 1930 came the last challenge, the first with the J Class, but again there was defeat, this time for Shamrock V.

And thus 1930 saw the end of the Royal Ulster YC's tumultuous three decades affair with the Holy Grail of sailing. Since then, other clubs have had their collective finger burnt by the America's Cup. But it usually promises more than it gives. Most recently, sailing has been bluntly reminded of its limited appeal as a spectator sport, even when packaged as America's Cup Plus. The 34th series in San Francisco may have provided some of the most exciting racing ever seen in the event's 164 year history. It made great television for aficionados. And it may have attracted 150,000 shoreside spectators over the length of the series. But let's get it into perspective. San Francisco's Number One tourist attraction is Alcatraz. This island with its former prison fortress linked to the likes of Al Capone and other adornments of American society attracts around a million visitors a year. No matter which way you slice the numbers, that's quite a few more than the America's Cup, it doesn't cost nearly as much, and it's much less trouble to run.

Which goes some way to explain why those of us who live for this crazy old vehicle sport of ours retreat into the happy dreamworld of old boats and their winding journeys through life, often to a wonderful re-birth. And the story of Tern is a classic of its kind. From Belfast Lough she headed some time or other to Cork, we don't quite know when, but we do know she was converted to a yawl for greater ease of handling in 1914. And she was certainly in Cork in the 1920s and 1930s owned seemingly by a loose syndicate, as different owners appear at different times depending on what event she is being entered for, and in 1929 she was one of five yachts taking part in the Irish Cruising Club's Founding Cruise-in-Company to Glengarriff, owned by Capt P F Kelly.

Happy days. Aboard Tern in cruising style, complete with enormous dinghy on the starboard deck, on her way to the founding of the ICC in Glengarriff in 1929 with Captain Kelly and Dr Dan Donovan enjoying the sail

Tern in Falmouth, July 1990. Rot had long since set in within her long and elegant Fife counter, so it had simply been chopped off. Photo: W M Nixon

Tern being overcome by the heat in Andraitx in Mallorca, October 2012. Photo: Patricia Nixon

Yet by 1947 according to Lloyds Register she was in Dun Laoghaire, owned by two members of the National Yacht Club, C E Hogg and M Healy. And then she turns up in Falmouth Harbour in the 1970s and stays there for some time, but she was restored to being a cutter, not with full rig but her mizzen had to be done away with, as there was rot in her long elegant Fife counter, so it was simply chopped off to become like a Laurent Giles stern.

It was then in a little yard in a hidden creek off Falmouth Harbour that she had her first major restoration, and with that she went to the Mediterranean. But by the Autumn of 2012 she was seen in Andraitx looking a bit sorry for herself, and very much for sale. And there she was bought and taken into the specialist yard in Palma, and at the end of December 2014 Patricia O'Connell and Alan Renwick turned up in Ireland and began a pilgrimage.

Alan Renwick and Ian Malcolm aboard the latter's Aura in Howth, December 30th 2014. Aura had Tern have just one year age difference, but the same builder. Photo: W M Nixon

This took them to Howth to see the Hilditch-built Aura (like Tern, she's number 7, and like Tern, at one time her mainsail was mixed up with a number 2). Then it was down to Crosshaven to meet Royal Cork archivist Dermot Burns, who was a fund of information and original material abut Tern's twenty-plus years on Cork Harbour. Then on north to Belfast Lough for a large gathering in the Royal Ulster, a party built around the Charley family, one of whose ancestors owned Tern in 1910, and also brought in folk like noted northern sailing historian Michael Clarke of Lough Erne, and Fife yachts historian Ian McAllister who now lives in Carrickfergus. So you can well imagine that information and ideas overload was a constant risk. But Patricia and Alan survived, they got back to Palma in one piece, the work on Tern resumed, and the Tale of Tern goes on.

There's a Fife hull in there somewhere. Tern in the restoration shed in Palma

Duncan Retains SB20 Title on Belfast Lough

#sb20– The battle finally ended yesterday evening on Belfast Lough to decide the Irish national championships for the SB20 Sportsboat class. Gold and Silver fleet results are available for download below. The margin being only 2 points between the front runners Ben Duncan and Mel Collins, it was Collins who had to mount the attack and Duncan to defend his slim advantage. Only one race was sailed and Royal Ulster YC race officer Robin Gray and his team got the slimmest window possible for a decider and sent the fleet off in 5 knots of breeze.

Ben Duncan and crew got the slight advantage at the start with Collins not quite getting the same boat speed off the line. Duncan rounded the weather mark in 3rd with Mel Collins and crew rounding in 10th. However Collins made a remarkable comeback to place 4th in the final race but it was Duncan who pulled off another race win to make it a 3,1,1,1,1 to Collins 2,2,2,2,4.

Second placed Mel Collins from Royal Cork at full speed

So Ben Duncan, Brian Moran and Joe Turner reign supreme in the class with an incredible second nationals title in a row. Adding that to his Scottish nationals title along with a practically clean sheet at all the regional events makes it his best season yet.

Third was Andrew and Ross Vaughan (4 5 4 5 1), 4th was class Chair Jerry Dowling helmed by Stefan Hyde (3 4 8 4 6) and 5th was Ger Dempsey and Chris Nolan staging a very impressive first season appearance in the class.

23 Boats Raced the Fiftieth Yacht Race Round Ailsa Craig

ailsacraig – K. Halliwell's 'She of the North' was the winner of Friday's Hamilton Shipping 50th Anniversary Ailsa Craig Race staged by the Royal Ulster Yacht Club.

The largest entry was class 1 in the twenty-three boat fleet followed by the CYCA Non-spinnaker Class. A new Class 5 was added for smaller boats.

#ruyc – Royal Ulster Yacht Club's (RUYC) fiftieth Ailsa Craig Race starts tomorrow evening at 8pm and is an important anniversary for the Northern Ireland Yacht Club.

A classic in the Northern Offshore yacht racing calendar, the course taking the fleet overnight round the famous rock at the mouth of the Clyde and back to Bangor.

Tomorrow, on June 15th, the club will stage the 50th anniversary race, the first of which was held in August 1962.

In that year the 11 ton sloop Tyrena, owned at that time by Dr and Mrs W Glover, was the first winner of the trophy, a silver replica of Ailsa Craig. Many of the original competitors, several of whom are now in their 80s, are expected to compete.

This special event, and indeed the other three races in the offshore series, will be sponsored by Hamilton Shipping, who have previously been generous supporters of Sigma 33 racing hosted by Royal Ulster.

Gordon Hamilton, Managing Director of the company, is delighted to be once again associated with racing at Royal Ulster: "Given the importance of Belfast Lough to our business, we like to support Royal Ulster Yacht Club, particularly whenever the club has worked so hard over many years to maintain offshore yacht racing in Northern Ireland. We hope the history attached to this year's Ailsa Craig Race will make things a little special for all competitors.'

The Sailing Instructions will set out the starting and finishing details; the race will start on Friday 15th June with a course that will take competitors from the Royal Ulster YC start line via the South Briggs Buoy (to port) around Ailsa Craig and back to the South Briggs Buoy (to starboard) and thence to the Finish Line also at Royal Ulster YC. There will be breakfast laid on for competitors who finish in the morning and a 50th Anniversary Dinner on the Saturday evening.

The Classes racing in this special 50th Anniversary event include IRC Unrestricted and No Spinnaker Divisions and also CYCA Unrestricted and No Spinnaker.

Ailsa Craig Race Celebrates 50th Anniversary

#RACING UPDATE - This summer the Royal Ulster Yacht Club will stage the 50th anniversary edition of the Ailsa Craig Race, one of the classics of the Northern Ireland offshore yacht racing calendar.

Many of the competitors from the inaugural race in 1962 - several of whom are now in their 80s - are expected to compete in the overnight challenge, which takes the fleet from Bangor to the rock at the mouth of the Clyde in Scotland.

The 2012 Ailsa Craig Race, sponsored by Hamilton Shipping, takes place on 15 June.