Displaying items by tag: Grace O’Malley

Tall Ship Grace O’Malley’s Stately Inaugural Progress Along Irish Coast Promises Worthwhile Maritime Future

In recent days, we’ve seen celebrations honouring the super-star young sailors who have brought major international sailing medals of gold, silver and bronze home to Ireland and their rightfully-delighted families and cheering local clubs. These are sailors whose special talent has been identified and encouraged at an early stage in a broadly maritime sociological environment, such that they almost automatically qualify for inclusion and support in what we might call the Fast-Track Flotilla.

But make no mistake about it, there has to be a very special talent present in the first place. And there has to be a preparedness for dedication to a level of hard work at fitness, combined with an almost continuous devotion to practice, which would arguably amount to cruelty were it not for the fact that it is usually the young Special Ones themselves who are setting this personal career pace, and where necessary ruthlessly dragging their supporting circle along with them.

Letting them start young. Laser Gold Medallist Rocco Wright in his Optimist-racing days

Letting them start young. Laser Gold Medallist Rocco Wright in his Optimist-racing days

Nevertheless, there’s no denying that often they start from relatively special positions in the first place, and thus it is timely to take an overview of one of the routes into sailing available to those who may not come from a sailing background or who even - though it is rare in Ireland – live at some distance from a place where sailing is regarded as just one of many parts of the local scene.

While noted sailing schools – of which the all-encompassing Rumball family’s INSS in Dun Laoghaire is the largest – play a very praiseworthy role in bringing people into the sport, as do clubs with an energetic local outreach programmes, there’s no doubt that when the Sail Training Brigantine Asgard II was in her prime, she was uniquely placed to bring young - and sometimes not-so-young folk – into a state of natural sea-awareness.

When the going was good. Captain Tom McCarthy (foreground) with the crew of Asgard II in Coruna in 1990 after being declared overall winners of the International Sail Training Plymouth-Coruna Race. Photo: Ted Crosbie

When the going was good. Captain Tom McCarthy (foreground) with the crew of Asgard II in Coruna in 1990 after being declared overall winners of the International Sail Training Plymouth-Coruna Race. Photo: Ted Crosbie

For Asgard II ticked all the boxes. She had a natural historical position, she was just big enough to be seen as the national flagship, she was instantly recognised in whatever Irish or foreign port she was visiting, and aboard her there was true equality in shared seagoing experience and the learning process. She was the living breathing camaraderie of the sea in one attractive and accessible package.

So when she sank - for still not really satisfactorily explained reasons - in the Bay of Biscay fourteen years ago, to be followed to a watery grave in Rathlin Sound two years later by the Northern Ireland 80ft ST ketch Lord Rank, despite the absence of any loss of life the Irish maritime community north and south went into a state of grief of such profundity that some of us still haven’t really got through the denial stage.

There are times when we really do believe that it’s all a bad dream, that Asgard II will sail into port in the morning. And beyond that, we find it difficult to accept that it seemed the Civil Service and most of the Government were glad enough to see Asgard II gone in 2008, as running a sail training ship does not fit easily into any Irish government programme, and at a political level there are proportionately very few votes – even in coastal areas – in promising to provide such a service.

But happily there are those who - instead of sinking into gloom – steadily moved into action, and the recent certificate awards ceremony of Coiste an Asgard’s successor Sail Training Ireland reminded us that at a more modest size, there are private-enterprise craft as diverse as the Limerick ketch Ilen, the ex-MFV Brian Boru and the chartered-in Pelican which provide berths for Irish trainees.

The former Brixham trawler Leader is a recent addition to the fleet in Ireland

The former Brixham trawler Leader is a recent addition to the fleet in Ireland

As well, from the north and lately seen in Dublin is the classic Brixham sailing trawler Leader, while for those whose offshore sailing ambitions are very specific, Ronan O Siochru’s Irish Offshore Sailing of Dun Laoghaire provides courses in Sunfast 37s which can culminate in the Dun Laoghaire to Dingle race, the Round Ireland, and the Fastnet Race, in which in 2021 they were top-placed Irish boat, and second – by minutes – in their class.

But while all this is well and good, the size of vessel in the established Irish-based sail-training fleet means that they’re lacking in what sail-training Dermot Kennedy of Baltimore – one of the original inspirers of the eventual Jack Tyrrell design – described as the “eye-popping” factor.

Way back in 1972 when ideas for replacing Asgard I were being tossed about, Dermot bluntly dismissed those who sought a modest-looking utilitarian craft by declaring their attitude was nonsense - the new ship should be an instantly-recognised clipper-bowed craft of significant size and classic appearance setting as many square sails as possible, and lighting up every anchorage she visited. And in 1981, he got his way. But in 2008, she was gone.

Enda O Coineen understands many things, but he has no comprehension whatsoever of the meaning of the word “No”.

Enda O Coineen understands many things, but he has no comprehension whatsoever of the meaning of the word “No”.

However, for some years now a contrarian who could match Dermot Kennedy any day for stubbornness has been beating the drum about a proper sailing training for the whole island, and that is Enda O'Coineen with what was originally the Irish Atlantic Youth Trust, but now seems to be the Atlantic Youth Trust plain and simple, overseen by a Board of Directors well peopled with the great and the good, with Peter Cooke recently succeeding Olympic Gold Medallist Robin Glentoran as President.

Nobody can accuse the AYT of being impatient, as they researched the project for years at every level to come up with proposals which would provide a ship well able to provide useful educational services beyond straightforward sail training. And from time to time, Governments north and south – when approached – made encouraging noises.

The Believer. Peter Cooke has taken on the demanding role of President of the Atlantic Youth Trust

The Believer. Peter Cooke has taken on the demanding role of President of the Atlantic Youth Trust

But in the uncertainties of pandemics and the current political situation, the need for leadership through action became increasingly evident, so when a suitable ship became available in Sweden on the second-hand market, they dropped the idea of building from new, and went for it.

And though pessimists would suggest that we’re probably at the least suitable time in at least ten years in which to bring a proposed all-island sail training vessel to Ireland, there’s something about the Grace O’Malley’s very presence which seems to generate goodwill, and while she looks impressive in harbour, she looks even better under full sail.

All of this you’ll have read in various disparate articles in Afloat.ie for several months and more now, but with the 164ft Grace O’Malley cleverly making her Irish debut in the recent Foyle Maritime Festival, the story is gaining momentum, and as Afloat.ie’s Betty Armstrong reported yesterday, she has since being making a quiet but favourable first appearance in Belfast.

Grace O’Malley – as seen in Belfast last week – looks very well in port……

Grace O’Malley – as seen in Belfast last week – looks very well in port……

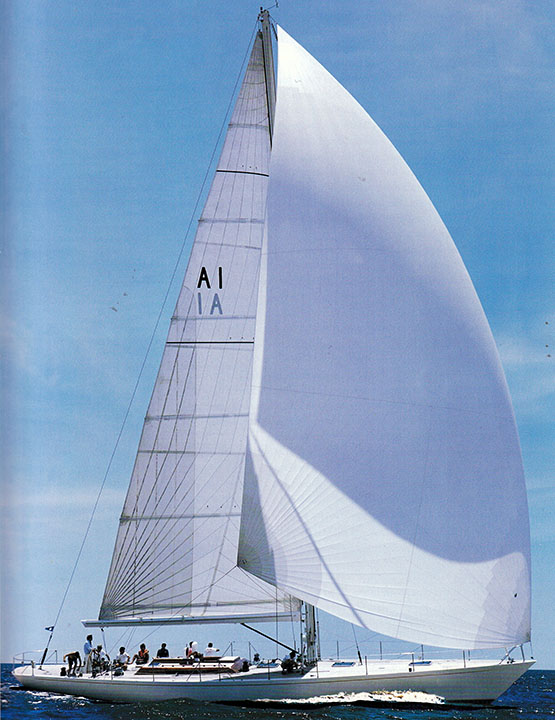

…….but she looks even better under sail and heading seawards

…….but she looks even better under sail and heading seawards

Her current duty commander is Captain Gerry Burns, who hails from a fishing background in West Cork but these days lives in County Down. He was a regular relief captain for Asgard II, and his passion for the realisation of the full potential of Irish sail training is a wonder to behold, so there’ll be a fervent atmosphere in Warrenpoint this weekend as Grace O’Malley will be in port.

Thereafter, what could become a circuit of Ireland’s main ports is the planned progression, and it would be only right and proper to include a visit to the Sea Queen Grace O’Malley’s island base of Clare Island, not least because the ship has two O’Malleys from there – Brian and Owen - in her crew, and they don’t deny direct descent from the woman herself.

The circle completed - Operations Manager Brian O’Malley hails from Sea Queen Grace O’Malley’s home place of Clare Island, and is of course descended from the famous mariner.

The circle completed - Operations Manager Brian O’Malley hails from Sea Queen Grace O’Malley’s home place of Clare Island, and is of course descended from the famous mariner.

In time, when fully operational next year, the Grace O’Malley will turn heads wherever she goes, and the programme will have developed to have a throughput of a thousand trainees annually. In Irish sailing terms, that’s a lot of potential seafaring talents, so who knows what new names of national and international maritime significance will emerge from the voyaging of the good ship Grace O’Malley. We wish her well.

Grace O'Malley to Visit Warrenpoint Port During Loughside Festival With Free Public Access to Tall Ship

Grace O'Malley, a 164-ft tall ship which drew considerable attention in Derry and Belfast as Afloat reported, and which is destined to serve the island of Ireland as a training vessel for young people as part of the Atlantic Youth Trust, is today to visit Warrenpoint in Co. Down.

Warrenpoint Port will be hosting the tallship Grace O Malley in support of the Warrenpoint Loughside Festival with the schooner remaining in the port until Tuesday 16th August (see dates and times below for free public boarding access).

Last month the schooner was purchased in Sweden by the Atlantic Youth Trust Charity (currently known as the Lady Ellen, if vessel tracking) as the tallship this morning is off the Down coast.

According to Warrenpoint Port, Grace O'Malley is to sail up Carlingford Lough and is expected to berth at the Town Dock Marina at approximately 12.30pm (subject to change).

The port is delighted to bring the tallship to the local community and to introduce young people across the island of Ireland to a possible maritime career.

In addition the maiden call of the tallship to Warrenpoint is to build on the excitement and interest created from the recent cruise ship visits so far this season as Afloat reported.

Over the course of the weekend the tallship will be open, free of charge (docked) to walk around and experience life on board. You can access the ship from the Town Dock Marina closest to the Vecchia Roma restaurant just off the Square in Warrenpoint.

Public Opening Hours (subject to change):

Friday 12th August 1.30pm- 3.30pm

Saturday 13th August 2.30pm-4.30pm

Sunday 14th August 11am-1pm

Monday 15th August 12 noon-3pm

Tuesday 16th August 12 noon-2pm

(Please note the port advises that the tallship will also be hosting a number of private events)

Access to the ship is restricted to tidal hours (to be confirmed each day) and numbers are limited at any one time. A queuing system will be in place and barriers will close 15 minutes before the closing time.

As a charity @Atlantic Youth Trust operates a gratuities box for anyone who wishes to donate to their efforts.

Please check Warrenpoint Port social media channels for updates before travelling to visit the ship as part of the Lough Side Festival and enjoy a visit to the Grace O Malley.

Grace O’Malley or in Irish, Grainne Ni Maille, was the head of the O Maille dynasty in the west of Ireland. She is a well-known historical figure in sixteenth-century Irish history and in popular culture often referred to as "The Pirate Queen" as she is reputed to be one of the most famous pirates and was considered to be a fierce leader at sea.

Far from being a ‘pirate ship’, the Grace O’Malley is Ireland’s most recently acquired Youth Development Tall Ship and made its first appearance on the island last week at this year’s Foyle Maritime Festival following its purchase by the Atlantic Youth Trust charity.

The Grace O'Malley arriving in Derry. It is hoped the ship can become a floating embassy for Ireland Photo: Lorcan Doherty

The Grace O'Malley arriving in Derry. It is hoped the ship can become a floating embassy for Ireland Photo: Lorcan Doherty

She was greeted by hundreds of enthusiastic festival goers on Thursday last and moored alongside Meadowbank Quay.

The Atlantic Youth Trust Charity was set up to connect Irish young people with the ocean and adventure while developing sustainability and supporting and protecting the environment.

It was formed by private individuals and organisations throughout the island of Ireland to offer youths an introduction to life at sea and is chaired by Round the World sailor Enda O'Coineen,

The Grace O’Malley is a 164ft long tradewind schooner purchased in Sweden last month to introduce young people across the island of Ireland to a possible maritime career.

She was built as a timber merchant schooner in Denmark in 1909 and was launched in 1980 to host 100-day guests and 37 overnight passengers.

Trainees on the deck of the Grace O'Malley

Trainees on the deck of the Grace O'Malley

The Grace O’Malley left Sweden on the weekend of July 9th for its maiden voyage with its new owners. “It’s a stunning ship and even people who aren’t sailing enthusiasts will be very interested to see it,” explained Catherine Noone from the Atlantic Youth Trust.

“We’re delighted that the first appearance in Ireland is at an event as large and high profile as the Foyle Maritime Festival”.

The Grace O'Malley at Meadowbank Quay in Derry

The Grace O'Malley at Meadowbank Quay in Derry

“The Grace O’Malley has been bought for the young people of Ireland by the Trust to give them an experience of sailing and create a pathway to a wide range of maritime careers,” Catherine continued.

“We want the ship to be as accessible as possible and that is why events such as the Foyle Maritime Festival are so important in reaching out to young people and giving them their first introduction to life on board a ship. It opens up such a wide range of careers to young people and ten days on board a boat with us can also help develop key life skills and provide a much-needed change of perspective.”

Climbing the rigging of the Grace O'Malley at the Foyle Maritime Festival

Climbing the rigging of the Grace O'Malley at the Foyle Maritime Festival

After six days crossing the North Sea from Western Sweden, with 40-knot headwinds at times, the ship arrived in spectacular fashion in Lough Foyle and was piloted from the village of Greencastle on the north bank by Harbour Master Bill McCann, under the Foyle Bridge, the second longest on the island of Ireland.

O’Coineen asked the question, “ Would we fit under the Foyle Bridge?” With four metre clearance they did!

And the Grace O’Malley did prove a big draw at the Festival with a constant queue of people waiting to go aboard.

The schooner left Sweden on July 15 with 20 crew onboard. The ship was captained by experienced and renowned Irish Captain Gerry Burns for its voyage across the North Sea, North of Scotland and then southbound to Derry.

The Grace O’Malley is a Youth Development Ship for all of the young people of the island of Ireland. Young people will experience sailing, teamwork, a change of perspective and also create a pathway to a wide range of maritime careers. This is a project that can truly change lives. H77

As reported in Afloat in January, O’Coineen, a former Director of Coiste an Asgard, says "we have long since championed the need to replace Ireland’s lost sail training vessel the Asgard II in a dynamic and creative new way". It is hoped the ship can become a floating embassy for Ireland at events home and abroad, ranging from Tall Ships races to trade events while all the time fulfilling her core youth and reconciliation mission. It is understood that a " mini-refit" will be required to suit Irish purposes.

According to O'Coineen, she will need some cosmetic work on deck and will need to be repainted. Much of the running rigging, now several years old, will need replacement.

Ireland’s Hopes for a Tall Ship Are Running High

What goes around comes around. When Enda O’Coineen’s Atlantic Youth Trust revealed their interest in acquiring a classic three-masted topsail schooner from Sweden last Autumn for multiple maritime functions, of which sailing training would only be one, it set bells ringing in many ways — most of them positive.

The warmest feelings were aroused by the classic appearance of the 164ft Lady Ellen. For the reality is that these days, the professional seafarers who undertake the demanding task of being responsible for the safety, well-being and instruction of dozens of other people’s children in sail training programmes are themselves expecting certain standards of onboard comfort.

In fact, the more fastidious expect accommodation which equals that provided for their colleagues serving in the best ships of the international merchant marine and the leading navies.

As a consequence, many modern tall ships are a very odd combination of classic clipper ship forward, and a sort of mini cruise liner aft. In some of them, this effect is achieved to such gross effect that it reminds you of the old saying that a camel is a horse designed by committee.

She looks like a proper classic sailing ship, and sails like one too

She looks like a proper classic sailing ship, and sails like one too

But when the first photos were released in Ireland of the Lady Ellen, everyone just gave a happy sigh. Her sweet appearance may be slightly marred by a sort of wheelhouse shelter right on the aftermost pin of the quarterdeck, but otherwise her deck cabins are of modest height, with the overall effect being one of harmony.

And for those with memories stretching back over many years, the appearance of the Lady Ellen was like a friendly ghost brought to life, as she is a reminder of the hopes of two great sea-minded people who pioneered the idea of an Irish tall ship at a time when officialdom seemed determined to obliterate any consciousness of our maritime potential.

The inspirational Arklow-based Lady of Avenel

The inspirational Arklow-based Lady of Avenel

One was Jack Tyrrell of Arklow, whose schoolboy summers as ship’s boy aboard his uncle’s trading brigantine Lady of Avenel were so central to the beneficial shaping of his character that his lifelong dream was to provide subsequent generations with the chance to share a similar experience.

The other was an inspirational teacher, Captain Tom Walsh, who ran the little Nautical College in Dun Laoghaire, and kept the flame of Irish maritime hopes alive in what was a very thin time for Ireland and the sea. One result of this was that in 1954, Jack Tyrrell designed for Tom Walsh some proposal drawings for a 110ft three-masted barquentine to serve as an Irish sail training ship.

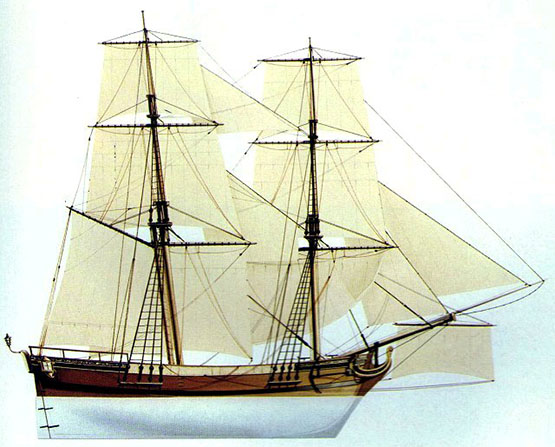

We’ve been here before: the 1954-proposed 110ft barquentine, designed by Jack Tyrrell for Captain Tom Walsh, is remarkably similar to the Lady Ellen

We’ve been here before: the 1954-proposed 110ft barquentine, designed by Jack Tyrrell for Captain Tom Walsh, is remarkably similar to the Lady Ellen

By the summer, this could be the Grace O’Malley

By the summer, this could be the Grace O’Malley

Captain Tom Walsh of the Nautical College in Dun Laoghaire – seen here in 1957 – was ahead of his time in sail-training ship proposals

Captain Tom Walsh of the Nautical College in Dun Laoghaire – seen here in 1957 – was ahead of his time in sail-training ship proposals

In the slow-moving 1950s, it was an idea before its time. And when Ireland did finally get a national sail-trailing ship in 1969, it was through a completely different route, with the repurposed Asgard, Erskine and Molly Childers’ 1905-built Colin Archer 51ft ketch used in the 1914 Irish Volunteers gun-running to Howth.

She was and is a fine little ship, now conserved by the National Museum and on display in Collins Barracks. But she was too small for the job, and very soon a movement was under way to have her replaced with a larger “mini tall ship”. In the February 1973 issue of Afloat Magazine, proposal drawings by Jack Tyrrell appeared of a ship inspired again by the Lady of Avenel, but of a more modest size at 83ft hull length.

By this time the sail training programme was in the remit of the Department of Defence, as it tended to be shunted around whichever government minister was interested in the sea — the choice was never extensive. But the newly-appointed Minister for Defence, Patrick Sarsfield Donegan TD of Co Louth, was keen on boats and sailing. He willingly undertook the Asgard programme. And he happened to see those plans one morning as he was starting to make a very thorough job of celebrating his saint’s day in his own pub, the Monasterboice Inn.

Jack Tyrrell of Arklow with Clayton Love Jr, Admiral of the Royal Cork YC and one of the founders — and the longest-serving member — of Coiste an Asgard

Jack Tyrrell of Arklow with Clayton Love Jr, Admiral of the Royal Cork YC and one of the founders — and the longest-serving member — of Coiste an Asgard

Thus there is absolutely no doubt that the decision to build the 84ft Tyrrell-designed and Arklow-built Asgard II was taken by Paddy Donegan on 17 March 1973, but it was March 1981 by the time she was in commission.

She gave excellent service, punching way above her weight on the national and international scene for 29 seasons, until in September 2008 she struck a semi-submerged object in the Bay of Biscay, and gradually but inexorably sank, with all the crew being safely taken off.

With Ireland going into economic freefall in the total crash of the Celtic Tiger, the then Government — to outside observers, at least — appeared to take advantage of the situation to divest themselves of the entire notion of a national sail-training ship and a government-administered programme to support it. This was so abundantly evident that dedicated maritime enthusiasts came to the conclusion that the only way forward was through a non-governmental trust functioning on an all-Ireland basis, and thus the Atlantic Youth Trust came into being under the inspiration of oceanic adventurer and international entrepreneur Enda O’Coineen.

There are hundreds of subtly different meanings to the word “no”, but Enda doesn’t understand any of them. He is totally resilient in face of setbacks, be they in business or when he’s alone out on the Great Southern Ocean. And he is of the opinion that general derision or a flat refusal is actually — if the other party only knew it — a cheery greeting and a positive reception of whatever way-out idea he is proposing.

Galway rules the waves: Enda O’Coineen with President Michael D Higgins

Galway rules the waves: Enda O’Coineen with President Michael D Higgins

Nevertheless, the Atlantic Youth Trust’s concept — developed by its director Neil O’Hagan to provide a ship partially based on the Sprit of New Zealand’s realised vision of a floating classroom and expedition centre as much as a sail training ship — was well received but difficult to grow in a time of national austerity, with political turmoil in the all-Ireland context.

But the idea had certainly never gone away, and while there are many reasons as to why it is now tops of the agenda once more. The fact that the Lady Ellen was for sale last September in western Sweden played a key role, with the excitement of the chase being heightened by the fact that it had been thought she’d been sold elsewhere.

Stripped down for winter, the Lady Ellen in Sweden awaits her new future in Ireland

Stripped down for winter, the Lady Ellen in Sweden awaits her new future in Ireland

However, that seemingly fell through, she came back on the market, and now the deposit has been paid by Atlantic Youth Trust supporters subject to all the usual legalities and technicalities, such that if everything proves acceptable survey-wise and under other headings, the deal has to be closed by the end of February.

While she was built as long ago as 1980 for a Swedish industrialist with personal attachments to the prototype, the 1911-built wooden trading schooner Lady Ellen, the current ship’s hull is in top-grade steel as used for submarine construction, so not surprisingly she came through a 2015 survey and major refit with flying colours.

This is one serious ship, built in submarine-quality steel to last for a very long time

This is one serious ship, built in submarine-quality steel to last for a very long time

Yet to the casual observer she seems to be all wood in her finish, and therein lies an extraordinary problem that will have to be faced by the AYT when, if all goes according to plan, the ship undergoes significant work with the Harland & Wolff shipyard in Belfast in the spring.

For her present accommodation is positively luxurious by sail training standards, though her seagoing credentials are impeccable with 17 transatlantic passages logged. Yet below decks, we’re talking of en suite cabins for around 35 in all, whereas the trust will be seeking to up the accommodation to at least 40 and probably 45 in all, with 30-35 trainees plus five experienced youth leaders and five professional crew.

The existing accommodation details may need significant amounts of unravelling in order to accommodate a total ship’s company of 45-plus

The existing accommodation details may need significant amounts of unravelling in order to accommodate a total ship’s company of 45-plus

The saloon — taking up the full width of the vessel — makes such extensive use of wood and varnish finish that you forget you’re on a steel ship

The saloon — taking up the full width of the vessel — makes such extensive use of wood and varnish finish that you forget you’re on a steel ship

Even the “basic” crew cabin reflects the “problematically high” quality of the interior finish

Even the “basic” crew cabin reflects the “problematically high” quality of the interior finish

When Jack Tyrrell was sketching out the accommodation for the Tom Walsh ship of 1954, he simply indicated space where the crew’s sleeping accommodation would be found. He may well have expected that the young people would be happily slinging a hammock from the deck beams.

But as the photos of the current ship indicate, while not totally luxurious, her accommodation is stylish, very well finished, glowing with the best of varnish-work, and generous with space. So some of it will have to come out, and we can only hope that it’s treated a little more kindly than the bits and pieces of the original Colin Archer interior for Asgard which, in 1968 when she was being converted for sail training by Malahide Shipyard, were brutally consigned to a bonfire.

The separate cabins emphasise the high quality of the finish

The separate cabins emphasise the high quality of the finish

With repurposing all the rage these days, some of the ship’s current accommodation could certainly find some interesting and useful functions ashore, or in other boats. But the fact is while the vessel is being bought reportedly for the attractive price of €1.78 million, unbuilding and rebuilding can be an expensive process, as can the necessary replacing of standing and running rigging, and perhaps some spars.

Thus, if all goes according to plan with the deal closed at the end of February, the current project of getting the ship in commission in her new form, with the necessary shoreside support systems up and running, will be very rapidly making significant dents in the overall budget of €3 million.

And we have to remember that while the gallant Asgard II succeeded in punching above her weight among much larger tall ships, this new vessel is twice as long overall, making her in volumetric terms very much more than simply twice as large. So it’s going to take a considerable and constant effort to keep her in optimal trim and at full functional level. For apart from anything else, a busy ship is a happy ship, but a 164ft three-masted topsail schooner is a lot of ship to keep busy.

Yet the very fact that the Grace O’Malley, as she’ll be popularly renamed, has now come centre stage is just the tonic that we all need at this time of tiny slivers of hope, when it’s just possible the light at the end of the tunnel is not entirely a total pandemic express train coming the other way. We wish her well.

She’ll be even more welcome than the flowers in spring – the Grace O’Malley may be coming to a port near you

She’ll be even more welcome than the flowers in spring – the Grace O’Malley may be coming to a port near you

Grace O’Malley was Busy when She Voyaged from Clew Bay to the Thames for Parlay with Queen Elizabeth

When the great sea warrior queen Granuaile of Mayo voyaged from Clew Bay to parlay with the then all-powerful Queen Elizabeth I in London, there was even more to it than was hinted at by Clew Bay Figaro sailor Joan Mulloy’s recent replication of the exploit, as reported in Afloat.ie.

For Granuaile – aka Grace O’Malley - really was a total sailor who much preferred to be afloat – she always felt restless when she had to spend the night ashore in one of her many castles which dot the shores of the bay and are found on the offshore islands too, the most visible being at the harbour in Clare Island.

That she was a right battle-axe who successfully managed to treat mere men as total inferiors is undisputed. So in a face-to-face with Elizabeth, it started off by looking as though it was a case of the immovable force meeting the irresistible object, as neither could or would speak the other’s language.

But then - God bless classic European culture – they reached a compromise by conversing in Latin. And far from being the zero-sum game of negotiation which everyone seems to expect these days, it was a win-win outcome with Granuaile heading for home with agreement reached.

Rockfeet, one of Grace O’Malley castles beside Clew Bay. She personally always preferred to be aboard ship day and night if at all possible

Rockfeet, one of Grace O’Malley castles beside Clew Bay. She personally always preferred to be aboard ship day and night if at all possible

However, the Gods decided that as everything had gone so well, it was time to take a hand with an extra test. So they made conditions so challenging after Granuaile’s galley had weathered Land’s End and tried set a course for southwest Ireland that the doughty skipper was forced to concede, and headed for southeast Ireland instead, reckoning that some direct contact with the homeland was increasingly necessary, and once in Irish waters her presence would be so respected that she could voyage in easier stages back to Mayo via the east, north and northwest coasts.

Now I know we may be compressing history a bit here, but as Mark Twain – who we seem to be quoting a lot these days – so neatly put it, never let the facts get in the way of a good story. Anyway, all went well with the re-routing until she reached Howth, and went ashore to the Baron of Howth’s then relatively new castle in expectation of traditional hospitality. Yet the gates were closed, and the Steward emerged to inform her frostily that His Lordship was not at home.

“Be reasonable, lads – do it my way”. Grace O’Malley provides a pep talk for her all-male crew

“Be reasonable, lads – do it my way”. Grace O’Malley provides a pep talk for her all-male crew

Like all Howthmen then as now, his Lordship was probably fulfilling a dutiful support role for the wife at the 16th Century equivalent of Supervalu a Sutton Cross, a task which can easily take a couple of hours, but that’s by the way. The problem is that the Steward bluntly turned away the unaccompanied Sea Queen from the gate (let’s face it, even then she wasn’t the sort of person you saw or expected to welcome every day), and in terms of Irish hospitality, this was an unforgivable sin.

However, in storming back to her ship, Granuaile came upon young Christopher St Lawrence, eldest son of the 9th Baron of Howth, playing with his pals on the beach near the harbour. She promptly kidnapped the boy, bundled him aboard the ship, and sailed off northabout for Mayo.

From Clew Bay she sent back a message that the boy would not be returned to his parents until they agreed that the gates of Howth Castle would never again be locked against friendly visitors, and that an extra place would always be set at the dinner table every night. The two conditions have been scrupulously maintained ever since – quite spooky when there are just two or even just one for supper – and the boy was returned unharmed.

Handy little place by the sea – Howth Castle (left) with Ireland’s Eye beyond

Handy little place by the sea – Howth Castle (left) with Ireland’s Eye beyond

While young Christopher St Lawrence may never have repeated the experience of sailing westward as round the north and northwest of Ireland as Autumn advances, this early instance of Irish sail training under a strict but enthusiastic skipper appears to have been generally beneficial. In adult life when he became the 10th Baron Howth, and while he could get into the feuds typical of the time, his charm and survival skills were such that he and his family were able to retain the Old Religion when it was definitely neither profitable nor popular to do so, and they have kept the Old Religion and their castle and its lands ever since.

That is, until now. As reported ad nauseum, after 842 years with the St Lawrence family, Howth Castle and its lands including the island of Ireland’s Eye have been sold to Tetrarch, the top end hotel people who are best known for owning and developing Mount Juliet in County Kilkenny. They certainly do things with a certain style. But nevertheless we should be told if that extra place will still be laid for dinner.

Why Shouldn't The Irish Be A Seafaring People?

We may be an island nation, but are we a maritime people in our outlook and way of life? It could be reasonably argued that we most definitely aren’t. On last night’s Seascapes, the maritime programme on RTE Radio 1, Afloat.ie’s W M Nixon put forward a theory as to why this should be so. It’s based on a premise so simple that you’d be very confident somebody else must have pointed it out a long time ago. Yet despite Nixon’s notion being in the realms of the bleeding obvious, even with the aid of Google we cannot find any other commentator or historian making a straightforward suggestion along these lines, but will gladly welcome proof to the contrary.

Why aren’t we Irish one of the world’s great seafaring people? After all, we live on one of the most clearly defined islands on the planet. And it’s an island which is strategically located on international sea trading routes, set in the midst of a potentially fish-rich sea. Our coastline, meanwhile, is well blessed with natural havens, many of which are in turn conveniently connected to our hinterland by fine rivers which, in any truly boat-minded society, would naturally form an integrated national waterborne transport system.

Yet the traditional perception of us is as farmers, cattle traders and horse breeders of world standard, while the more modern view would include our growing expertise in information technology and an undoubted talent for high-powered activity in the international aviation industry. Then too, there is our long-established standing in the world of letters and communication and the media generally. Yet although there are now encouraging signs of a healthier attitude towards seafaring and maritime matters, particularly in the Cork region, for most Irish people the thought of a career in the global seafaring and marine industry simply doesn’t come up for consideration at all.

So why is this the case? I think the basic answer could not be simpler. The fact is, nobody ever walked to Ireland. The prehistoric land-bridges to Britain had disappeared before any human habitation occurred here. Our earliest settlers could only have arrived by primitive boat, and that was only ten thousand or so years ago. But even then, boats were still so basic that the often horrific seafaring experiences would have generated the pious hope of having absolutely nothing further to do with the sea and seafaring for the passengers, once they’d got safely ashore. And that attitude was handed down from one generation to the next.

While the south of England, with its land-bridge still connected to continental Europe, had experienced quite advanced human habitations for maybe as long as 400,000 years, Ireland by contrast was one of the very last places in the temperate zones to be taken over by human settlement, and those first settlers must have come by boat of some sort.

So even in terms of the relatively brief period of human existence on Earth, the settlement of Ireland is only the blink of an eye. Thus in talking of “Old Ireland”, we’re talking nonsense. Ireland is a very new place in terms of its human history. Yet although we’ve only been here ten thousand years, all the archaeological research points to the relatively rapid development of a complex society with some very impressive monuments being built in a relatively short period, and by a society which had become highly organised and technologically advanced within a compact timespan. Newgrange in County Meath - 5000 years old, and eloquent evidence of the sophistication of Ireland of the time

Newgrange in County Meath - 5000 years old, and eloquent evidence of the sophistication of Ireland of the time

Newgrange’s location close to the River Boyne (top right) is a reminder that while basic river transport had become quite highly developed, in this era Irish seafaring was still in its earliest and most primitive stages despite the people’s ability to undertake the advanced calculations used in the construction of Newgrange.

So these were not a people who were just passing through. The earliest Irish were determined to make something special of their new home with some colossal and impressive sacred buildings and structures. To some extent this reflected the possibility that they were totally committed to creating a meaningful life in Ireland perhaps because they saw themselves as now marooned on it.

This sense of being marooned would have become embedded and emphasised in the compact family and tribal groups which very slowly spread across the island as a basic farming and hunting people. The inherited memories of the horror of the voyage to attempt to reach Ireland, in which many lives must have been lost at sea, would have been passed down from generation to generation, and we can be sure that the potential hazards of such an enterprise would lose nothing in the re-telling and embellishment of the ancient stories around the family hearth.

In other words, the longer your people have been in Ireland, then the greater would be your inherited sense of the risk in seafaring. Put another way, you could say that the very earliest Irish were not a seafaring people because the very earliest Irish mammies were absolutely determined that their sons were not going to seek a living on the dreadful sea. In the way of Irish mammies, they made sure that everyone knew this, and they have continued to do so to the present day.

If this emphasis on the adverse effect of inherited unhappy memories seems to over-state the case, consider the circumstances of the ancient people of the Canary Islands. When the Spanish voyagers first discovered the Canaries at a time not so very distant from Columbus’s voyages to America, they thought initially that the islands were uninhabited. It was only later that it was discovered that the highest mountain regions were home to an isolated people who were distantly related to the Berbers of North Africa.

In the remote past, these mountain people’s ancestors had somehow – possibly unintentionally – made the 62 mile voyage across from Africa. It is only eight miles further than the shortest distance between Wales and Ireland. But the seas are significantly warmer, which you’d expect to be a favourable circumstance for encouraging further voyaging. Yet having finally struggled ashore, those first Canary Islanders were very soon distancing themselves from the sea and seafaring.

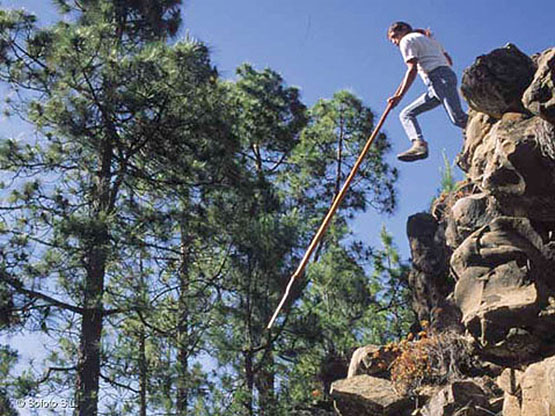

The Shepherd’s Leap (Salto del Pastor) of the Canary Islands. The earliest islanders in the Canaries turned their backs on boats and the sea so completely that they retreated away from the coasts and went to live in the mountains. There, they developed a unique way of life including this primitive pole-vaulting – now a traditional sport – in order to descend cliffs or traverse ravines

The Shepherd’s Leap (Salto del Pastor) of the Canary Islands. The earliest islanders in the Canaries turned their backs on boats and the sea so completely that they retreated away from the coasts and went to live in the mountains. There, they developed a unique way of life including this primitive pole-vaulting – now a traditional sport – in order to descend cliffs or traverse ravines

Any small enthusiasm they might have had for boats soon disappeared completely, such that they now have no shared knowledge or memory of boats at all. And up in the mountains, their most remarkable talent is the ability to pole vault down into or across the ravines – the Shepherd’s Leap - in order to travel about in their vertiginous homeland, which was seen as preferable in every way to the real dangers of seafaring.

In a Thomas Davis lecture for Seascapes a dozen or so years ago, I discussed the specialised nature of those whose primary interest in the early days of Irish settlement lay in seeing seafaring as a viable way of life. So relatively rare were such people that I reckoned at the time that this talent for exploiting the diverse wealth which the sea offered would provide them with useful survival mechanism for themselves and future generations of their families.

But I now realise that I got it totally wrong. Absolutely the opposite must have been the case. Once you and your people had got safely to Ireland in the first wave of settlers, the seafaring was still so basic and consistently dangerous that having nothing further to do with it was a much better way of ensuring the continuing survival of your genetic stock, whereas producing a family of would-be sailors could see the end of the line in a very short few years.

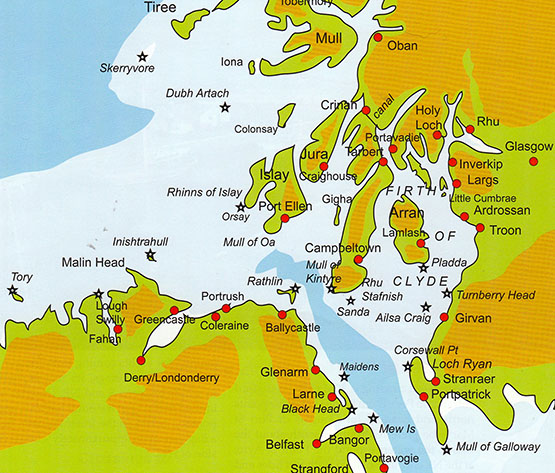

Although the popular view in Ireland is that our earliest ancestors must have sailed direct from Iberia, it seems to me that Western European seafaring would have been so primitive in those days ten thousand years ago that the first settlers must have voyaged across in nondescript vessels from the most easily reached part of the nearby British land, which is the large island of Islay off southwest Scotland.

As it happens, DNA testing on the current population of southwest Scotland indicates that they too have significant elements of our Iberian stock. Thus there is a shared gene pool, and the earliest Irish most likely came by the easiest route from Scotland, whose people in turn had travelled overland from Europe via England.

If that seems a bit hard to take for those of us who like to think that we’re essentially a Mediterranean people left out in the rain, that we’re essentially a formerly seafaring race who came directly by sea from our ancestral homelands in the Basque region, be consoled by the fact that many centuries later Scotland itself was to undergo conquest by invaders from Ireland of the Scoti tribe, who gave a new name to a country formerly dominated by the Picts.

However, that was very much later, when seafaring technology had greatly advanced, and people could regularly sail across the waters between Ireland and Scotland with some confidence. But when the earliest land-starved pioneers were contemplating crossing to Ireland from Scotland, they would have first looked for the shortest route. The absolute shortest distances between Scotland and northeast Ireland is in the North Channel between the Mull of Kintyre and Fair Head in County Antrim. There, the straight line distance is barely a dozen miles, yet you are facing one of the most tide-riven, roughest and coldest sea channels in Europe. And should you make it safely across, the landing at the nearest point on either side is decidedly difficult.

Further south, the shortest distance between the Mull of Galloway in southwest Scotland across the North Channel to northeast County Down is only 20 miles, but here again in early times the landings were inhospitable on either side, and the tides could be ferocious in their adverse impact.

The crossings between Scotland and northeast Ireland which would have been faced by the earliest settlers. While the shortest distance between Kintyre and Fair Head to the east of Ballycastle is just over 12 miles, and the distance between Portpatrick and the nearest part of County Down is barely twenty miles, the entire North Channel between Rathlin Island and the Mull of Galloway is tide-riven, notoriously rough, and with the coldest sea temperatures on the Irish Coast. The earliest voyagers in very primtive boats would thus have had a better chance of a safe crossing, with more options as to their ultimate landfall, by setting off from Port Ellen in Islay, and having avoided the notorious tide race to the southwest of the Mull of Oa, then shaped their course to wherever the winds suited to make a landfall between Inishtrahull and Rathlin. The oldest human settlement in Ireland is at Mount Sandel near Coleraine. Plan courtesy Irish Cruising Club

But if you approached the Scotland-Ireland passage from the mainland of Scotland to the northeast, gradually working your way southwestwards through the southern Hebrides and gaining some seafaring experience with short inter-island hops until you were strategically placed at the natural harbour of what is now Port Ellen on the south shore of Islay, then the prospects were better. You might have still been all of 25 miles from Ireland, but it was a more manageable crossing. You had much greater choice in your possible destinations in making an Irish landfall, as you’d the entire Irish coast from Fair Head to Malin Head to aim for.

In reasonable weather, you could see where you were going, and with prevailing westerly winds there’d be a good chance it would be a relatively easy beam reach if you happened to have a primitive sailing rig, though the likelihood is the early boats were paddled, or rowed in primitive style.

Whatever the method of propulsion, there’s no disputing that one of the oldest sites of human habitation in Ireland is right in the middle of this northern coastline, at Mount Sandel on the River Bann in Coleraine. Yet no matter how much research and archaeology has been undertaken at Mount Sandel and at other ancient sites, no evidence of significant Irish human settlement has been found which goes back any further than ten thousand years.

As it happens, it was ten thousand years ago that mankind first developed the genetic mutation that enabled our ancestors to digest dairy products. But another five thousand years were to elapse before the first cattle were brought to Ireland to find that the place might have been invented for them, and cattle became a source and a measure of wealth. This new socioeconomic development pushed the sea and any form of seafaring even further down the social scale as a viable career option. Who would think of being a fulltime sea fisherman in a land noted as flowing in milk and honey? And even though water transport using rivers became a significant part of Irish life – notably in Fermanagh where the Maguires were to have a water-based mini-Kingdom - the sea was still viewed with suspicion, while the consumption of fish – whether from salt water or fresh – was regarded as socially inferior to eating meat.

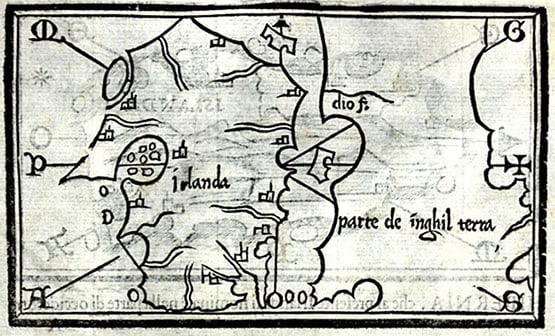

Mediaeval map of Ireland. It’s just possible that the island-studded inlet shown on the west coast is the Maguire-ruled Lough Erne, but more likely it is Clew Bay given prominence through Grace O’Malley.

It was only with improvements in seafaring technology and the general seaworthiness of ships that later generations and new groups of settlers might have brought a more positive attitude towards the sea. Then there was a period of about 1200 years – rudely ended by the first arrival of the Vikings around 795AD – when Ireland was remarkably free of invasions, yet enough marine technology had developed in the island for a brief flowering of Irish seafaring with the extraordinary voyaging of the Irish monks.

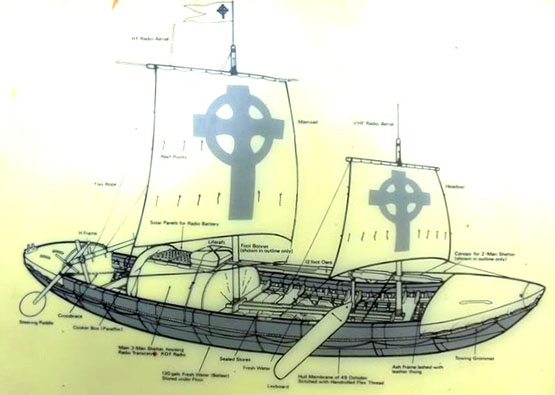

It has been argued by some scholars that there was no such person as St Brendan the Navigator. But undoubtedly there were great seafaring monks, and those of us who say that if it wasn’t St Brendan then it was somebody else of the same name will occasionally make the pilgrimage across from Dingle to rugged little Brendan Creek close under the west slopes of Mount Brandon on the north shore of the Dingle Peninsula, and wonder again at those Irish men of limitless faith setting out from this sacred spot into the great unknown in light but able boats.

But as it was seaborne asceticism which they sought rather than wealth, it was seen as a highly specialized and rather odd interest when most of the people were much more readily drawn to epic tales of profitable cattle raiding.

Details of Tim Severin’s oxhide “giant currach” with which – in 1976-77 - he showed that the supposedly mythical Transatlantic voyages of St Brendan the Navigator were technically possible. The St Brendan - which with Denis Doyle’s encouragement was built in Crosshaven Boatyard in 1975-76 – is now on permanent display at Craggaunowen in County Clare.

Then came the Vikings. Say what you like about the Vikings - and everybody has an opinion – but the reality is that their longships represented a quantum leap in naval architecture development. They brought state-of-the-art voyaging in versatile ships way ahead of anything seen before. Yet in time the Vikings were in their turn sucked into the Irish way of doing things, and far from turning Ireland into a seafaring nation, they seem to have literally burned their boats and set up home ashore, gradually absorbing the negative attitude towards the sea of their new neighbours, and taking on board the inevitable anti-seafaring attitudes of their new mothers-in-law

It wasn’t immediately as simple as that, of course. For a while, Ireland was the focal point of the Vikings’ sea trading routes along the coasts of western Europe, while Dublin had the doubtful distinction of being the biggest slave market in the constantly changing Viking western empire, which wasn’t really a territorial empire in the traditional sense, but was more a sphere of active influence and commercial and raiding activity. But it was undoubtedly a major centre which was totally dominated by all Viking activities, including ship-building, and the return to Dublin in 2006 of the 100ft Sea Stallion of Glendalough, a re-creation of one of the biggest Viking ships ever built (in Dublin in 1042), was a telling reminder of just how much Dublin had been to the fore in Viking life, while this video is a timely reminder of the great project completed in Roskilde ten years ago.

Inevitably, people of Viking descent were becoming a significant element in the Irish population, and even today we would naturally expect someone called Doyle to have something of the sea in their veins. Yet the Irish capacity for absorption of newcomers into the old ways of thinking has worked here too. The most common Irish surname today is Murphy. It means sea warrior. While those of us with maritime interests in mind would like to think it referred to an ancient tribe who went forth from Ireland to do successful battle on distant seas, we know in our heart of hearts that the Murphys are descended from warriors – mostly Vikings - who came in from the sea.

In time, they were enticed into domesticity by comely maidens who in due course became the formidable Irish mammies who prohibited any seafaring by their sons. Indeed, so far are most Murphys removed today from the sea that in some parts of the world the name is still a patronising nickname for the potato, something which is useful enough in its way, but its only maritime link is through fish and chips.

After the Vikings and then the Normans – who were really only Vikings with some slightly less rough French manners put on them – subsequent invasions were English-dominated, and the growth of British sea power was done in a manner which made sure that any Irish role in it was strictly of a subservient nature.

Rockfleet Castle in County Mayo, reputed deathplace of Grace O’Malley in June 1603. She was everything she shouldn’t have been, and in heroic style. She was Irish yet a mighty seafarer in command of her own ships, and a woman, yet a ruthless ruler of power and wealth who could combat men on equal terms.

Of course there were local heroes who tried to oppose this, the most renowned being Grace O’Malley, the Sea Queen of Connacht. But even when people of English descent tried to establish a separate Irish seafaring identity, as happened with the merchants of Drogheda, their aspirations would be slapped down by the dominant power and control from the government in London and the influence of the merchants of Bristol.

However, the government only had to look the other way for a moment before there was some local maritime enterprise was trying to flourish, and in the late 18th and early 19th Century the North Dublin smugglers, privateers and pirates of the little port of Rush in Fingal, people like Luke Ryan and James Mathews, were pace-setters in Europe and across the Atlantic, striking deals with Benjamin Franklin among others.

Depending on the state of international hostilities, sometimes their privateering trade could be quite open, and in Dublin the Freeman’s Journal of 23rd February 1779 reported that “we find the little fishing village of Rush has already fitted out four vessels, and one of them is now in Dublin at Rogerson’s Quay, ready to sail, being completely armed and manned, carrying 14 carriage guns and 60 of as brave hands as any in Europe”.

A late 19th century privateer, built for speed. When times were good for privateering, the little port of Rush in Fingal could provide a flotilla of these craft, which at other times could be kept hidden in the Rogerstown Estuary

The Admiral from Mayo. Being press-ganged by the Royal Navy was one of the many career-changing events which resulted in William Brown from Foxford becoming the founder-Admiral of the Argentine Navy.

But the majority of Irish seafarers were employed only in the humblest roles afloat, and often through the activities of the shore-raiding involuntary recruitment drives of the press gangs of Britain’s Royal Navy, However, this could produce some wonderful examples of unexpected consequences. The most complex was William Brown, of Foxford in Mayo, who had somehow risen to be a Captain in the American merchant marine when he was press-ganged into the Royal Navy, and after many vicissitudes, he ended up as a merchant in Buenos Aires. There, thanks to his unexpected acquisition of experience in naval warfare by courtesy of the Royal Navy, he became the founder of the Argentine Navy and an Admiral, as one does…..

Then there was the 18th Century Patrick Lynch of Galway, …….according to some stories, he was press-ganged. Be that as it may, the family made their fortune eventually in South America and a descendant, Patricio Lynch, owned the ship Heroina which played a significant role in Argentine history. The family continued to prosper in many directions, such that one decendant was Che Guevara, while another is the yacht designer German Frers, whose own pet yacht (which he gets little enough opportunity to use, as he is so busy designing boats for others) is called Heriona in honour of the family’s complex historic links through the sea with Ireland.

Yacht designer German Frers sailing his personal 74ft sloop Heroina in the River Plate. The boat is named in honour of the historic ship which belonged to his ancestor Patricio Lynch.

But while a very few of the young Irishmen press-ganged by the Royal Navy may ultimately have prospered in unexpected ways, the vast majority most definitely didn’t. Most came to a horrible end, while those who had managed to escape the press gangs’ clutches, together with the rest of the bulk of the native population, were reinforced in their inherited distrust of seafaring in any form.

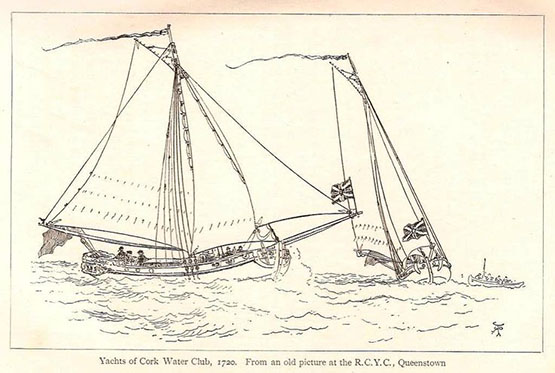

Thus although we may now feel pride in the fact that the world’s first recreational sailing club was established with the Water Club of the Harbour of Cork in 1720, it’s difficult to avoid the conclusion that those great Munster landowners and merchants who founded it were partly doing it subconsciously just to show how very different they were from the ordinary run of Irish people in their attitude to the sea.

First instance of the “have nots” and the “have yachts”? The establishment of the Water Club of the Harbour of Cork in 1720 was a remarkable achievement, but if anything it emphasised the fact that the vast majority of Irish people had no enthusiasm or capability for the sea. Courtesy RCYC.

As for the official attitude when the Irish Free State finally came into being, its was so painfully sea-blind that we still need to draw a veil over its attitude, only noting that the first significant voyage under the new Irish ensign was made by one of that much-maligned class, a yachtsman. This was the great venture round the world south of the capes by Conor O’Brien of Limerick with his little Baltimore-built Saoirse between 1923 and 1925.

Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse departs Dun Laoghaire on her world- girding voyage on 20th June 1923.

O’Brien was to find Ireland so stultifying in its outlook after his return that he sailed away to live elsewhere, and we have to accept that for several decades the official approach reinforced the notion that being interested in the sea is un-Irish. So if we hope to change this attitude which still lingers today, a useful first step is to accept that for many of us, being non-maritime is the most natural thing in the world – we’ve had it instinctively from the very beginning, it’s in our handed-down and repeatedly-instilled inherited memories from the time when our most distant ancestors struggled ashore from battered little boats somewhere on the north coast, knowing that many others had died, and would die, trying to do the same thing.

Far from trying to pretend that this attitude doesn’t really exist, surely a much better way is to accept that it does, but that we’ve researched a perfectly valid explanation as to why this is so. Thus the way forward for Ireland to fulfill her maritime potential is to realize why this attitude is there in us, and take mature steps to offset it.

The fact is, in dealing with the sea, the Irish people have never had a level playing field. We’ve had to live with it and our inherited memories of being on it in very adverse circumstances. Unlike continental land dwellers, we have had no choice in the matter - we don’t see the sea as somewhere excitingly new with endless possibilities, we see it only with inherited distrust. And the determination of the current wave of walking migrants from the Middle East into Europe to attempt the sea crossing at only the narrowest part is further dreadful evidence of this.

But in another area of human endeavour, we’ve shown that we can do the business in competition with other nations. When aviation began to become part of everyday life a hundred years ago, it was unknown territory for all mankind. In terms of getting to grips with flying, it was a level playing field for all.

Yet here we are now in Ireland, an island in the Atlantic which is playing an extraordinarily active and central role in many aspects of aviation management and development, and certainly punching way above our weight. Looking at what we have been able to do in the air, it is surely time to look again at what we might do with the sea if we can look at it from a fresh perspective, and adapt the same can-do energies of the Irish aviation industry to the business of seafaring.

It’s time and more to shake off the old fears of the sea, while always maintaining a healthy respect for its undoubted power. That is best done by being in the vanguard of maritime technological development. And down around Cork Harbour, they’re doing that very thing. It’s just possible that, despite our ingrained anti-maritime attitude, we are beginning to view the sea in a more healthy and positive way. And it’s from our great southern port that we’re beginning to get inspiring leadership as the sea beckons us towards fresh opportunities.

So what, if nobody ever walked to Ireland? So what, if our distant ancestors had a very cold, very wet and very rough time getting here? It’s time to move on. Time to get over it. Time to start seeing the sea in a sensible way.

The little ship that carried the maritime hopes of a new nation. Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse in dry dock, showing the tough little hull that was able to register a good mileage most days in the Southern Ocean while still sailing in comfort. Yet when he returned to Dun Laoghaire in 1925 to complete his voyage with a rapturous homecoming reception, Conor O’Brien was soon to find that beneath the welcome there was increasing official indifference in the new Free State to Ireland’s maritime potential.