Displaying items by tag: Arctic

Arctic Sailor Wins £2,500 for Powerful Climate Change Story

An Arctic sailor from Norway has won £2,500 cash for his account of climate change on the island of Svalbard. Jon Amtrup’s article was the judges’ first choice in Yachting Monthly’s Brian Black Memorial Award 2022, which seeks to promote and encourage adventurous sailors to explore environmental issues and to document them in writing and photos.

Glaciers on the Arctic island of Svalbard have retreated more than a kilometre in 12 years, a rate of more than 100m a year. Norwegian sailor Jon Amtrup has witnessed the changes first hand, having sailed to Svalbard regularly over more than a decade.

Glaciers on the Arctic island of Svalbard have retreated more than a kilometre in 12 years

Glaciers on the Arctic island of Svalbard have retreated more than a kilometre in 12 years

His evocative account of the desolate beauty and incredible wildlife of the island demonstrates a deep love for this landscape, but puts it in stark contrast with the global effects of climate change, as well as the local effects of mass tourism, oil exploration and other threats to the environment.

Jon was awarded a prize of £2,500, thanks to the sponsorship of the award by marine electronics company B&G, as well as a trophy of a barometer and clock mounted on hand-crafted elm wood by Les Silkowski. The award also included a donation of £1,500 to UK-based marine conservation charity Sea-Changers.

The judges, including Dee Caffari and Mike Golding, chose Jon’s as the winning article because of its clear communication of the biggest environmental challenge of our time, seen through the lens of one small island group. The writing was beautiful, brought to life by the stunning photographs of crewmember James Austrums.

The article can be read here

Jon Amtrup said: “I am truly honoured to receive the Brian Black Memorial Award. The severe threat that climate change poses to the ocean is something I have focused on for a long time. The climate in the Arctic is changing way faster than the rest of the world. Winning the award encourages me to keep going with my work documenting this area, and the money will go towards Gate to the Arctic to help educate young people about how they can make a difference.”

Jon Amtrup Leaving Tromsø

Jon Amtrup Leaving Tromsø

Runners up prizes were awarded to Niklas Sandström for his article ‘The Beautiful Baltic’ about the impact of pollution in the Baltic, and to Tobias Carter for ‘The Arctic is Changing Colour’ about his scientific expedition from France to Greenland. The articles will be published in Yachting Monthly and on www.yachtingmonthly.com during 2023.

Mike Golding said: “Each of this year’s 18 high quality entries describe visible issues around the world from our oceans in places on the forefront of climate change, but that most of us will never get to see. Jon Amtrups winning piece eloquently captured his observations of the receding ‘permanent’ ice front in the North – while at the same time highlighting the complex contradiction of the visitors who travel to witness the same – inevitably at yet further cost to the planet.

“One hopes that each of these visitors can, like Jon, communicate what they’ve seen so that ultimately, we all learn to tread lighter on the earth towards a future where, just perhaps, ‘climate change’ describes a world getting cooler again.”

Receiving the donation for Sea-Changers was charity trustee Tanya Ferry, who said: “The Brian Black Memorial Award's focus on communicating environmental issues is closely aligned with Sea-Changers’ core value of giving back to the sea. Sharing first hand witness of environmental damage brings the challenge faced by our oceans into sharp focus and highlights the issues addressed by our grant funding which delivers practical action on the ground in the UK. .

“This donation from the Brian Black Memorial Fund will allow us to keep delivering projects. It is crucial that we continue to build partnerships with marine businesses and other organisations to enable the distribution of funds to grassroots projects making a real difference around the UK coastline.”

The Brian Black Memorial Award was established last year in order to commemorate the lives of Brian and his wife Lesley Black.

Brian was a lifelong sailor, a television journalist for RTE in Ireland, UTV in Northern Ireland, and later through his own production company. He was also a passionate advocate for the marine environment, writing and filmmaking about the crises facing fragile Arctic ecosystems. His wife Lesley blazed a trail for women in sailing, becoming the first female yacht club commodore in Northern Ireland, and was an author in her own right.

The late Brian Black in Svalbard

The late Brian Black in Svalbard

Brian and Les passed away in 2020 and 2019 respectively, and this award was established by their family and Yachting Monthly in memory of them, and to encourage more sailors to use their unique access to tell stories about the environment that the world needs to hear.

Hydrophones Dropped Off Greenland Recording Sounds of Melting Arctic Icebergs to Fuel Irish Artist’s ‘Ocean Memory’ Project

An Irish artist is part of an international expedition that’s dropping hydrophones into the waters off Greenland to record the sounds of melting icebergs.

According to the Guardian, Siobhán McDonald will use the recordings from the underwater microphones in a mixed-media installation to explore human impact on the world’s oceans.

Over the next two years, the hydrophones will capture the sounds of melting Arctic sea ice and under subaquatic audio every hour — with the results being used both in scientific research and as part of a musical score McDonald will create with a composer.

My floating studio on expedition in the deepest part of the Greenland ocean. Just passed the awesome Greenland glacier yesterday. #arctic #water #northernlights #painting pic.twitter.com/Mk8sxSgh9W

— Siobhan McDonald (@SioMcDonald) October 11, 2022

“I’m interested in hearing the acoustic pollution,” the artist says. “The sea levels are rising and that will have an impact I’d imagine on the sound range and on all the biodiversity.

“Sound is fundamental in the ocean and Arctic animals. Hearing is fundamental to communication, breeding, feeding and ultimately survival. It speaks of the necessity of paying attention to the pollution we are causing to the ecosystems around us.”

The Guardian has much more on the story HERE.

Ireland’s West Coast Arctic Sailing Fan Logs Tenth Iceland Visit And Third To Greenland

Nick Kats of Clifden and originally America is always looking to the north for new cruises with his hefty 39ft Danish-built Bermudan ketch Teddy. And when we say “north”, we mean Arctic voyaging and a continuing fascination with Iceland and Greenland, for Nick and the Teddy every so often shape their course for high latitudes in much the same way most of the rest of us would contemplate another cruise to West Cork.

When Teddy with her international crew returned recently to Clifden without fuss or fanfare, it marked the completion of Nick’s tenth visit to Iceland, and his third detailed cruise in East Greenland. And as his voyages have included going on north to Jan Mayen, one of his crew managed to get a crystal-clear image of that remote island’s often fog-shrouded icy peak of Beerenberg, which is a rare pearl indeed.

Seldom seen, never forgotten……as recorded on one of Teddy’s ten Arctic cruises, the rarely fully visible Beerenberg on Jan Mayen is one of the most epic sights in high latitudes cruising

Seldom seen, never forgotten……as recorded on one of Teddy’s ten Arctic cruises, the rarely fully visible Beerenberg on Jan Mayen is one of the most epic sights in high latitudes cruising

In fact, thanks to his online-recruited crew inevitably including some top class photographers, the collected images of the Teddy Arctic cruises make for an impressive and informative display. You can get the flavour of it in this year’s cruise blog Teddytoarctic2022.blogspot.com. And “flavour” is the operative word , for in addition to many other interests, Nick is a nutritionist and an organic grower at his place in West Connemara, which gives added insight to the many meals – some of them decidedly experimental – consumed during the course of this well-fed venture.

MEETING DANU FROM GALWAY

Yet while the assumption is that Arctic voyaging boats will be largely on their own, and will be the only visitor when they get to some hidden little port, one point of particular interest in this tenth northern cruise was the number of other boats now regularly cruising in the region, some of which they knew already. Thus they met up with Peter Owens and his researching crew aboard Danu from Galway, and as Nick drily records: “We socialized”. Where two Irish-based boats are involved, those two words are open to any and many interpretations.

Nick Kats is very much his own man

Nick Kats is very much his own man

Greenland cruising expects some isolation, as with Teddy at this abandoned Innuit village, but there was also some high-powered socialising with sailing legends

Greenland cruising expects some isolation, as with Teddy at this abandoned Innuit village, but there was also some high-powered socialising with sailing legends

NORTHABOUT FROM CLEW BAY SAILS ON WITH ALL-FEMALE CREW

Then there was a real blast from the past with a get-together at Scoresbysund with Northabout, the purpose-built alloy-constructed expedition yacht put together by owner Jarlath Cunnane of Mayo and Paddy Barry and their team more than twenty years ago. The boat built, they sailed Northabout out from Westport to an astonishing career which included a global circumnavigation via the two northern routes, and two awards of the ultra-elite Blue Water Medal of the Cruising Club of America.

In this the Centenary Year of the CCA, that in itself is enough to remember with celebration. But Nick Kats was further pleased to report that they found Northabout - now under French ownership - to be “one very happy boat - eight crew on board, all women, four sailors, three mountaineers, and one photographer.”

A true sailing marathon man met up with was Trevor Robertson, going solo on his Alajuela 38 – he logged his 400,000 ocean miles quite some time ago. And then there were Jurgen and Claudia Kirchberger from Austria with the Americas-circuiting La Belle Epoque – you can find more about them through Fortgeblasen.

The successful end of a great era – Northabout returns to Clew Bay after her award-winning Arctic global circuit

The successful end of a great era – Northabout returns to Clew Bay after her award-winning Arctic global circuit

Men of the west and the Arctic – Jarlath Cunnane with Dr Mick Brogan and some of Northabout’s many crews at Westport Quay. Northabout continues Arctic voyaging, but now under French ownership

Men of the west and the Arctic – Jarlath Cunnane with Dr Mick Brogan and some of Northabout’s many crews at Westport Quay. Northabout continues Arctic voyaging, but now under French ownership

GREENLAND CRUISING GUIDE

Another memorable gathering was with Germany’s senior Arctic voyager Arved Fuchs with his very traditional Dag Aaen. So clearly there are times when the North Water seems more like a highway than a destination. And the numbers visiting will be likely increased by John Henderson and Helen Gould from Scotland - another cruising team met by the Teddy crew - for they are sailing along through ice and clear water alike, preparing “a quality sailor’s guide” to Greenland.

Germany’s Arved Fuchs has long found his vocation in Arctic cruising

Germany’s Arved Fuchs has long found his vocation in Arctic cruising

Pedants of language will wonder whether that will be a high quality publication, or a guide aimed at high quality sailors, or indeed if sales are going to be limited to members of “the quality” who happen to go sailing. Have it as you wish. But meanwhile Ireland’s west coast now scores remarkably well for seasoned Arctic sailors, with Jarlath Cunnane up on Clew Bay, Nick Kats in Clifden Harbour, Paddy Barry (just back from Svalbard) at Mannin Bay near Ballyconneelly, and Peter Owens back home with Vera Quinlan and their family near Kinvara. It’s a formidable line-up.

“Peace after stormy seas….” – Nick Kats’ Teddy (centre) in her sheltered drying berth at Clifden Quay. Photo: W M Nixon

“Peace after stormy seas….” – Nick Kats’ Teddy (centre) in her sheltered drying berth at Clifden Quay. Photo: W M Nixon

Two Irish Ketches Push The Limits In The Arctic

It is said that you have to be prepared to wait until the 15th July in the average season before you can contemplate a successful venture into the most heavily-iced parts of East Greenland. Whether or not global warming has moved this date significantly forward remains to be seen, but in line with the established experience, the Clifden-based naturopath, environmentalist and Arctic-sailing enthusiast Nick Katz and his crew with his hefty Danish-built steel ketch Teddy – usually a familiar sight at Clifden Quay in Connemara - have stationed themselves in Iceland after voyaging north from Ireland, and their passage toward East Greenland is now top of the agenda.

Nick Katz’s yellow-hulled steel ketch Teddy (centre) at Clifden Quay in Connemara Photo: WM Nixon

Nick Katz’s yellow-hulled steel ketch Teddy (centre) at Clifden Quay in Connemara Photo: WM Nixon

A many of many interests – Nick Katz of Clifden

A many of many interests – Nick Katz of Clifden

Meanwhile in the Northeast Atlantic, the long distance warming effects of the North Atlantic Drift - often described with some inaccuracy as the Gulf Stream – means that serious voyaging into High Latitudes can be undertaken much earlier, and it was in the first week of June that Dublin Bay Old Gaffers President Adrian “Stu” Spence departed north with his Voyager 47 El Paradiso.

“Everything rolls neatly away”. Adrian “Stu” Spence’s Vagabond 47 ketch El Paradiso in Poolbeg Y&BC marina in Dublin Port

“Everything rolls neatly away”. Adrian “Stu” Spence’s Vagabond 47 ketch El Paradiso in Poolbeg Y&BC marina in Dublin Port

His previous boat – also cruised to the Arctic - was the incredibly ancient 1873-vintage former Bristol Channel Pilot Cutter which came with - and kept - the name Madcap. Thus Skipper Spence is obviously averse to changing boat names, despite the fact that El Paradiso is just about the last thing anyone would think of in going to Svalbard/Spitzbergen and beyond, the main focus of the current Spence voyage.

Seafaring veterans: Joe Pennington of the Isle of Man, Dickie Gomes of Strangford Lough and DBOGA President Adrian “Stu” Spence in a serious discussion, probably about Manichaen philosophy…..Photo: W M Nixon

Seafaring veterans: Joe Pennington of the Isle of Man, Dickie Gomes of Strangford Lough and DBOGA President Adrian “Stu” Spence in a serious discussion, probably about Manichaen philosophy…..Photo: W M Nixon

After the challenges of Madcap’s utterly traditional rig, the ship’s company of El Paradiso – which includes serial High Latitude sailor and Blue Water Medallist Paddy Barry – find themselves dealing with the ultimate convenience setup in which everything – in theory at least – conveniently rolls away. The word is that going north via the Faroes, they’ve already experienced at least one exceptional storm. But the stories will be much longer and more varied than that when El Paradiso finally comes home.

“A man of the mountains and the sea” – Blue Water Medallist Paddy Barry is aboard El Paradiso for the voyage to the High Arctic

“A man of the mountains and the sea” – Blue Water Medallist Paddy Barry is aboard El Paradiso for the voyage to the High Arctic

When long-distance American sailor Nick Kats – now 62 - arrived into Clifden in far west Connemara nearly ten years ago with his 39ft steel Bermudan ketch Teddy, it started a fascinating new chapter in an already interesting life. For although his vocational training had turned him into a skilled carpenter and shipwright, his aptitude was as a sailor, he was also a doctor specialising in natural medicines, and in the exceptionally-varied environment of this part of Ireland’s always fascinating Atlantic seaboard, he was to find an area rich in possibilities, and his lifelong interest in foraging acquired new dimensions.

Many of many parts – for Nick Kats, this will be his third voyage to East Greenland

Many of many parts – for Nick Kats, this will be his third voyage to East Greenland

So although since 2012 he has had a longterm plan of sailing back to his home territory in the US’s Pacific northwest - ideally by using the Northwest Passage – events and changing circumstances have managed to prevent it, or at least put it on a very long finger. Certainly, he has made exploratory voyages to the High Arctic. But as often as not, he seems to have intentionally ended up well east of Greenland’s southern tip of Cape Farewell, way up around Iceland and Jan Mayen and East Greenland, and then Teddy invariably returns to her familiar winter berth, comfortably drying out at low water against the picturesque quayside in Clifden.

Teddy (centre) at Clifden Quay in the early days – there has been some building done beside her berth since this photo was taken

Teddy (centre) at Clifden Quay in the early days – there has been some building done beside her berth since this photo was taken

Apart from becoming part of the Clifden and west Connemara community, where he now has a shore base with a house set deep in that Land of the Sea, Nick Kats was already in several communications groupings when he arrived thanks to his eclectic range of interests, while he is also in a very special group of sailors in being deaf. Thus internet communications are a Godsend for him in recruiting crew, and the blogs by himself and various crewfolk hint at the diversity of characters that the wanderings of Teddy attract, such as Pierre the French chef who came aboard with rumours of experience in some very famous kitchens.

The Master Forager in his den – Nick Kats in Teddy’s comfortable saloon with some interesting ingredients to hand

The Master Forager in his den – Nick Kats in Teddy’s comfortable saloon with some interesting ingredients to hand

He’d been met through Hegarty’s boatyard at Oldcourt where he’d been working as a boatbuilder with Liam Hegarty, the restorer of Ilen among many other major projects. Yet somehow Pierre managed to spend a long period sailing on Teddy without cooking a single meal. But as Nick can rustle up superb food, occasionally from some unlikely ingredients, that was no problem.

We learn of this from crewman Josh, a New Zealander who claims with some pride to have no fixed abode, who tells also how they all get along with Nick’s virtually total deafness since his birth in France 62 years ago. It seems they simply take it for granted or forget about it as time passes, learning to face him fully when talking in daylight, while at night there’s something resembling telepathy to keep things moving along.

At her own pace, in her own time – Teddy is the epitome of the ocean voyager. Photo: Kenneth Whelan

At her own pace, in her own time – Teddy is the epitome of the ocean voyager. Photo: Kenneth Whelan

Not that Teddy is an excessively labour-intensive boat, as she is one of those rare but wonderful craft which can easily be made to steer herself on most points of sailing. Designed and built in steel as one of two in 1988 by Arne Hedlund of Denmark, her design certainly gives a nod to Colin Archer. But she’s very much her own boat, with a transom stern which provides valuable cockpit and deck space right aft, where a classic canoe-sterned Redningsskoyte design from Archer tends to be distinctly cramped.

The ocean dream – Teddy self-sailing while dolphins play around the forefoot

The ocean dream – Teddy self-sailing while dolphins play around the forefoot

In fact, Teddy is a boat of moderation in everything, being neither too wide nor too narrow, neither too heavy nor too light, with as much accommodation as can reasonably be fitted without reaching sardine-can territory. Her hull balances easily, and having a ketch rig increases the options for sail combinations to minimize helm load while still providing driving power such that – like Slocum’s Spray – once set in the grove, she just goes effortlessly on steering herself for miles and miles, the ease of it all shortening the apparent distance.

Nick Kats’ pleasure in all this is such that, although he was in East Greenland waters as recently as last year, yesterday (Monday) Teddy departed from the comfort of Clifden, outward bound for his third visit to that remote area beyond Iceland, over towards Greenland, and up to Jan Mayen. There, the ice cover is certainly much less than it was when Lord Dufferin made his pioneering high latitude cruise with the schooner Foam in 1856, as a result of which the charts of that rugged and remote island still show a small cove named Clandeboye Creek on the eastern shore, far indeed from the luxuriant ‘Gold Coast’ of North Down where Dufferin’s ancestral lands were centred around Clandeboye House.

Beerenberg on Jan Mayen as seen from Teddy in today’s conditions, above an ice-free sea. Photo: Alex Hissting

Beerenberg on Jan Mayen as seen from Teddy in today’s conditions, above an ice-free sea. Photo: Alex Hissting

Beerenberg suddenly appears through a gap in the clouds above the fog and the ice around Lord Dufferin’s Foam (lower left) in 1856

Beerenberg suddenly appears through a gap in the clouds above the fog and the ice around Lord Dufferin’s Foam (lower left) in 1856

Teddy’s current voyage is limited only by the fact that two of the crew – Dutch finance student Arjan Leuw (24) and Italian architect Piero Favero (33) - have flights booked out of Iceland on 6th September, following which Nick and remaining Irish crewman Aodh O Duinn (29, and a veteran of tall ships) expect to head for home and Clifden double-handed.

But just what some of the remote ports and settlements that they expect to visit will make of a boat coming in from far beyond the seas in this time of COVID-19 remains to be seen. As things are, it is quite an achievement to have assembled an international crew and get free to voyage towards distant horizons and remote snow-covered peaks.

Meanwhile, there is much busy research currently under way among various cruising and long-distance organisations as to just what is or is not possible in the Arctic, where we instinctively feel that the disease will not be so rampant, thanks to sparseness of population and the purity of air.

Will it be as fresh and healthy as it looks? Northwest Iceland as seen from Teddy last year

Will it be as fresh and healthy as it looks? Northwest Iceland as seen from Teddy last year

Whether or not that is the case is a moot point. As it is, we cannot help but notice that, through the month of June, many frustrated Irish sailors were sustained by the wonderful thought of the one-armed voyager Garry Crothers successfully battling alone across 3,500 miles of the Atlantic in order to get home to Derry.

And now, the mantle of our sailing dreams has been taken over by a highly individualistic owner-skipper who has not let profound deafness limit his joy in voyaging and savouring the special nature of the High Arctic cruising grounds. Our thoughts are with the crew of the Teddy, and thanks to Damian Ward of Clifden Boat Club, we have this drone footage of the ketch taking her low-key departure from Clifden Quay, and heading out for other places beyond the northern seas.

Arctic Researchers Network for Ireland

The Marine Institute in collaboration with the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade launched the Network of Arctic Researchers in Ireland (NARI) last Friday.

NARI aims to create, maintain and develop an informal all-island network of Arctic researchers in Ireland to facilitate the collaboration of scientific activities linked to the Arctic, and to provide independent scientific advice to the public and policymakers.

Irish sailors have voyaged to both the Arctic and Antarctic in recent times. Last Summer Gary McMahon's restored Ilen project went to Greenland and the Arctic circle. Jamie Young’s Frers 49 exploration yacht Killary Flyer from Ireland's west coast travelled to the Arctic in 2013 and 2019. And this year Round the World Sailor Damian Foxall led a mission to Antarctica.

According to the IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere, the extent of Arctic sea ice is declining and is getting thinner. Glaciers and ice sheets in polar and mountain regions are also losing mass, contributing to an increasing rate of sea-level rise, together with expansion of the warmer ocean. Sea level rise will increase the frequency of extreme sea-level events and warming oceans are disrupting marine ecosystems.

With significant demand for greatly enhanced knowledge and services to observe the changes in our oceans, NARI aims to enhance collaboration and promote Irish-based Arctic research activities, seek international polar cooperation and support the next generation of Arctic scientists.

President of NARI, Dr Audrey Morley of National University of Ireland, Galway said, “The coordination of research efforts on a regional, national and international scale is becoming increasingly urgent in order to address the emerging environmental and societal pressures on the Arctic region, which are of global significance. NARI will support a greater scientific understanding of the Arctic region and its role in the Earth system.”

Dr Audrey Morley will be leading a survey on the Marine Institute’s marine research vessel the RV Celtic Explorer later this year to improve our understanding of marine essential climate variables in the Nordic Seas. The Marine Institute is providing ship-time funding for this research survey and funding Dr Audrey Morley’s Post-Doctoral Fellowship (Decoding Arctic Climate Change: From Archive to Insight) in support of improving our understanding of Arctic climate change and ecosystems.

Dr Paul Connolly, CEO of the Marine Institute said, “As an Arctic neighbour, Ireland is exposed to the effects of a warming ocean, such as rising sea levels, increasing storm intensity and changing marine ecosystems. Scientists based in Ireland can make a real and meaningful contribution to Arctic research, and help to develop and implement adaptation responses from local to global scales. The Marine Institute is delighted to be supporting a network which will foster impactful research into the causes, manifestations and impact of Arctic change.”

Since 2018, the Embassy of Ireland in Oslo and the Marine Institute have sponsored early career researchers to attend the Arctic Frontiers Emerging Leaders. It is an annual program held in Tromsø, Norway, which brings together approximately 30 young scientists and professionals from around the world with interests in Arctic security, Arctic economy and Arctic environment.

The Marine Institute and Dept Foreign Affairs have launched an informal Arctic researchers network

The Marine Institute and Dept Foreign Affairs have launched an informal Arctic researchers network

Ciara Delaney, Regional Director at the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, said: “The Department of Foreign Affairs is delighted to host today’s round-table meeting of Irish-based Arctic researchers. Given the impact of climate change and the increasing relevance of strategic developments in the Arctic, the Arctic region is of growing importance to Ireland. A previous roundtable meeting in 2019 demonstrated considerable interest for the establishment of a national network of researchers to identify and take forward areas of common interest on Arctic issues. Building on this initiative, we are delighted to officially launch the new Network, together with the Marine Institute of Ireland. I hope that NARI can contribute to developing a strong, research-led, evidence base for Ireland’s growing engagement with the Arctic region.”

The new all-island network (NARI) brings together multidisciplinary scientists from the National University of Ireland Galway, the University of Limerick, the National Maritime College of Ireland, Cork Institute of Technology, Queens University Belfast, National University of Ireland Maynooth, University College Dublin, Trinity College Dublin and University College Cork.

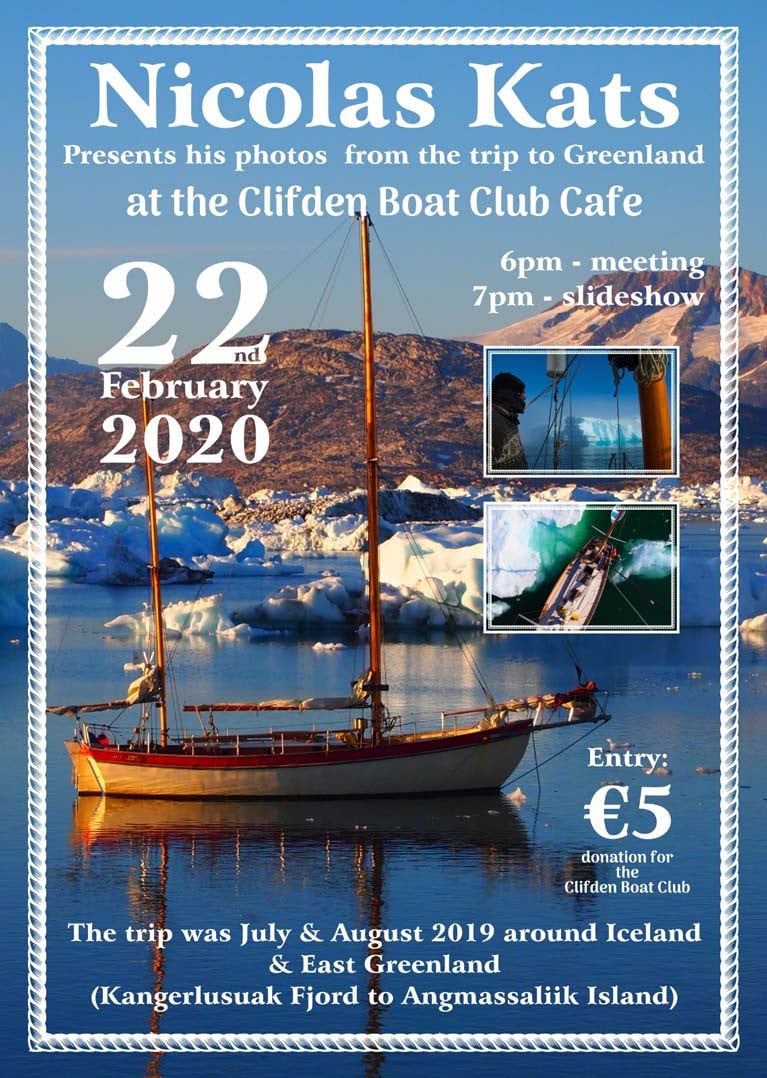

Arctic Cruising Comes to the Warmth of Clifden on Saturday night

The further west you go in Ireland, the warmer is the hospitality. So despite the current ferocious weather and the fact that Clifden in Connemara is well out into Ireland’s Atlantic frontier, the mood will be friendly and warm in Clifden Boat Club this Saturday night as Commodore Donal O Scannell welcomes members and guests for American skipper Nick Kats’s profusely-illustrated unveiling of his recent Arctic voyaging with his hefty Danish steel-built Bermuda-rigged 39ft ketch Teddy.

It is quite a few years since Nick and Teddy arrived into Clifden for a visit of undefined length, and during that time he has built up a reputation in Connemara for his skills as an acupuncturist and naturopathic doctor. But a return to his home in Oregon by way of the Northwest Passage was always on the horizon. However, it slipped down the agenda as he made exploratory visits to Greenland waters, and became bewitched by the place.

Thus last year’s cruise to the north was clearly made with no intention of trying for the Northwest Passage at all, as it took him to Eastern Greenland and included a circuit of Iceland before returning to Clifden. Just like that. It’s all very remarkable, and if you’re looking for something truly different in Connemara this Saturday night, we strongly recommend a visit to Clifden Boat Club for a unique experience.

Irish Northabout’s Great Arctic Circumnavigation to Feature at Sutton Dinghy Club on Thursday

Eight Irishmen and their 47-foot boat Northabout left Westport in June 2001 to sail the Northwest Passage north of Canada and Alaska. Nobody had ever sailed this in an East/West direction which is against the prevailing tides and winds. The crew endured hazards of ever-moving ice and navigation through narrow channels of open water.

They photographed the harshly beautiful landscape and superb wildlife on their way. The boat was designed specifically for polar exploration and built by Jarlath Cunnane of Mayo, and eventually she returned to Clew Bay after completing an Arctic circumnavigation of the world with a transit of the Northeast Passage north of Russia.

One of the crew was Gary Finnegan who has been a cameraman and filmmaker for over 30 years. As well as crewing on this journey Gary filmed the trip from start to finish.

Gary is coming to Sutton Dinghy Club on Thursday, March 14th at 7.30pm to show this great film and to answer any questions you have on the night.

Ireland Supports Heavy Fuel Oil Ban From Arctic Shipping

#Shipping - Ireland supports a move toward banning the use of heavy fuel oil from Arctic shipping, following a meeting of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in London earlier this month.

Plans to develop a ban on heavy fuel oil (HFO) from Arctic shipping, along with an assessment of the impact of such a ban, were agreed upon during the IMO’s Marine Environment Protection Committee, which closed on Friday 13 April.

The move was welcomed by the Clean Arctic Alliance campaign, which called on IMO member states to “make every effort” to adopt and implement a ban on “the world’s dirtiest fuel” by 2021.

“Thanks to inspired and motivated action taken by a number of IMO member states to move towards a ban on heavy fuel oil, Arctic communities and ecosystems will be protected from the threat of oil spills, and the impact of black carbon emissions”, said Dr Sian Prior, lead advisor to the coalition of 18 NGOs working to end HFO use as marine fuel in Arctic waters.

“A ban is the simplest and most effective way to mitigate the risks of HFO – and now we’re calling on the IMO to ensure that this ban will be in place by 2021. Any impact assessment must inform, but not delay progression towards an Arctic HFO ban, and member states must ensure that Arctic communities are not burdened with any costs associated with such a ban.”

The proposal to ban HFO as shipping fuel from Arctic waters was co-sponsored by Finland, Germany, Iceland, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Sweden and the United States.

The proposal for a ban, along with a proposal to assess the impact of such a ban on Arctic communities from Canada, was supported by Australia, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Ireland, Japan, the League of Arab States, Poland, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, and the UK.

Support from Denmark is particularly notable as it is the sixth Arctic nation to support the ban, according to the Clean Arctic Alliance.

“With Denmark the sixth Arctic nation to back a ban on HFO from Arctic shipping, the green alliance of Arctic nations have sent a clear message to the IMO,” said Kåre Press-Kristensen, senior advisor in the Danish Ecological Council.

“With both the Danish government and the Danish shipping industry united to ban HFO, we hope to gain further international support for the ban from more nations and progressive parts of the shipping industry. Next step will be to engage Greenland further in planning and preparing for the ban.”

Alaskan native Verner Wilson, senior oceans campaigner for Friends of the Earth US and a member of Curyung Tribal Council, with Yupik family roots in the Bering Strait region between Russia and the US, said: “I am grateful that IMO has advanced a ban on HFO to help protect Arctic communities and our traditional way of life.

“For thousands of years we have relied on our pristine waters and wildlife – and now the IMO has taken this important step to help protect our people and environment.”

The Clean Arctic Alliance says there “widespread support from within the industry” for a HFO ban, citing the Association of Arctic Expedition Cruise Operators, the Norwegian Shipowners Association and icebreaker company Arctia as among those who have expressed support.

Connemara Sea Scouts Solve Mystery Of Marine Research Buoy

#ArcticBuoy - A marine research buoy found on the Connemara coast by local Sea Scouts recently had drifted over 6,000 kilometres across the Beaufort Sea, Arctic Ocean and Atlantic to Ireland.

The buoy, around half a metre in diameter, was found at Lettermullen by the scout troop during an exploration of their local beach.

Michael Loftus, leader of Gasógaí Mara na Gaeltachta (Connemara Sea Scouts), said they often find flotsam and jetsam washed up on the shore, which they can usually identify.

“However, little did we know that this new find would uncover a world of discovery relating to the buoy being launched from an aircraft in the Arctic Ocean and travelling thousands of kilometres to land on the west coast of Ireland.”

The Marine Institute, which works on a series of projects where autonomous instruments are deployed into the ocean for marine research, was contacted to help solve the mystery of where the red buoy came from.

“Although the buoy is not an Argo float that is typically used by the institute as part of the national Argo float programme, we were delighted to help the Sea Scouts establish that the buoy is in fact an Airborne Expendable Ice Buoy, which came from as far away as the Beaufort Sea,” said Diarmuid Ó Conchubhair of the Marine Institute.

The International Arctic Buoy Programme involves a number of different countries including Canada, China, France, Germany, Japan, Norway, Russia, and the United States.

The programme maintains a network of drifting buoys in the Arctic Ocean that are used to monitor sea surface temperatures, ice concentration, and sea level and support weather forecasting. The buoys are also used for validating climate or earth system models which inform the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports.

Each buoy in this programme has an identification number that is used to track its location in the Arctic Ocean using a type of satellite communication system.

“Using the number marked on this buoy [#4800512], we were able to establish that this particular buoy had been deployed by an aircraft over five years ago in the Beaufort Sea, north of the Yukon and Alaska, west of Canadian Arctic islands,” said Ó Conchubhair.

Dr Eleanor O’Rourke, oceanographic services manager at the Marine Institute, explained: “Researchers involved in the International Arctic Buoy Programme decide where to deploy buoys, particularly where the status of sea-ice may be changing.

“Most of the buoys are placed on sea ice, but some are placed in open water in some of the most remote parts of the world's ocean, where it is difficult for research vessels to access.”

Airborne Expendable Ice Buoys have an average lifespan of 18 months and around 25 to 40 buoys operate at any given time.

“The buoy last reported its data in 2014 and it is likely that it ran out of battery power and spent the last three to four years at the sea surface travelling via wind and ocean surface currents,” said O’Rourke.

In 2007, Ireland became a member of the international Argo programme, which uses robotic instruments known as autonomous Argo floats that report on subsurface ocean water properties such as temperature and salinity via satellite transmission to data centres.

Using a fleet of around 4,000 autonomous floats around the world, the Argo array is an indispensable component of the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS).

“Similar to the buoys used by the International Arctic Buoy Programme, Argo floats collect and distribute real time information on the temperature and salinity of the ocean,” said Ó Conchubhair, who is vice chair of the European Argo Programme.

“Argo floats; however, measure these variables from the upper 2,000m of the ocean and help to describe long-term trends in ocean parameters such as their physical and thermodynamic state.”

This information is required to understand and monitor the role of the ocean in the Earth's climate system, in particular the heat and water balance.

Click here for more information about Ireland’s involvement in the Argo programme. You can also track and look at data from Irish Argo floats at Ireland’s Digital Ocean.

Four years ago, another Arctic device was found on the North West Coast and exhibited by Transition Year students in Co Mayo, as previously reported on Afloat.ie.