Displaying items by tag: Judge Boyd

Howth Harbour Thoughts From Home

This weekend has the Irish Sailing Youth Pathway Championships being staged at Howth, and despite the weather the place is buzzing. From being a harbour abandoned in embarrassment for twenty years in the middle of the 19th Century, the peninsula port has gradually evolved to develop a vibrant balance between fishing harbour, sailing centre, and visitor magnet. Longtime local W M Nixon tries to tell it like it is in Howth when seen from the inside.

Howth has most of the advantages and few enough of the disadvantages of being an island. Head home eastward through the isthmus at Sutton Cross (and don’t forget you’re heading eastward - Howth is Dublin’s Eastside, while the Northside is in nearby Ireland), and you shed your Irish identity to become a Howth person. Ideally, this means you become a complete nobody among many other nobodies, for that’s the way we like it.

It must be some sort of defence mechanism, for there was a period in the middle of the 1800s when the powers that be in nearby Ireland preferred to forget our very existence. You see, when the vital links of government between Dublin and London were being maintained by special sailing packet ships, Howth was important because the island of Ireland’s Eye (even in this blog we haven’t the space to explain how it got its name), which is upwards of half a mile off the distinctly rough village, was able to provide an element of natural shelter at a time when Dublin Bay and Dublin Port tended frequently to be disaster areas for shipping.

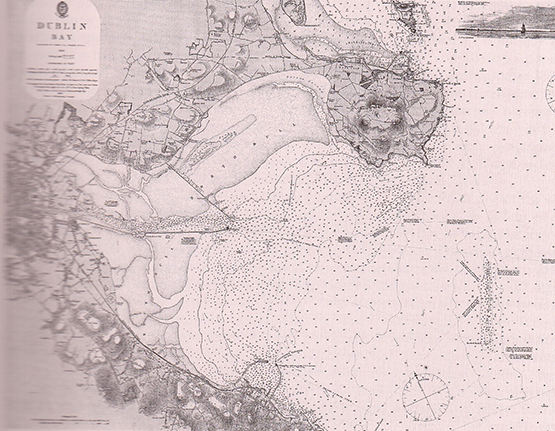

There were times when the only shelter in Dublin Bay itself was in the very limited space inside Dalkey Island, where a sailing ship could easily be trapped, whereas Howth Sound inside Ireland’s Eye, while north of Dublin Bay and beyond the Baily, nevertheless enabled a potentially embayed ship to cut and run. And yes, that is how the phrase originated.

The north side of Dublin Bay in 1692. The Government’s cross-channel packet boats favoured the roadstead anchorage at Howth inside Ireland’s Eye as it provided better shelter than the exposed bay itself, yet there was more space to cut and run than could be found in Dalkey Sound

Thus they built an inn in the village so that people passing through to London, and waiting for the packet boat, would not impose unduly on the hospitality at Howth Castle of the St Lawrence family, unless they were awfully important. And then when the engineer Thomas Telford was commissioned to build a road linking London with Dublin through Holyhead, naturally on the Irish side he followed the official view of things and continued his road through Howth and on towards Dublin, in light of the fact that offical policy was that the Government harbour would be built at Howth.

And build it they did, from about 1807 onwards, with John Rennie in charge. But with the gathering prosperity and increased trade after the final end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, the movement for the improvement of Dublin port and the building of an “asylum harbour” at Dunleary within Dublin Bay gained traction, and by 1817 what would soon become the highly-fashionable Kingstown Harbour was already under construction before Howth Harbour was even properly finished.

Once the new harbour had been completed at Dunleary on the south side of Dublin Bay and re-named Kingstown, the smaller shallower harbour at Howth was forgotten about for twenty years

Nevertheless Howth continued as the official mailboat port until 1834, by which time even the most stubborn official mind had to recognise that everyone else had long since gone Southside. So at last the powers that be followed. And in doing so, they tacitly agreed that the best way to deal with the memory of the ENORMOUS expenditure of building shallow sandy Howth Harbour was to ignore the place’s very existence for as long as possible.

The local fishermen continued to use the sandy creek of Balydoyle as their main port as they’d always done, while Howth seems to have been out of bounds to just about everyone. It was declared an inviolate Royal Harbour which might be of strategic value in the event of attack by Barbary pirates or Eskimo marine commando units or whatever, and for maybe fifteen years Howth simply slumbered, quietly silting up.

But by the 1850s, the growth of the fishing industry through travelling fleets of trawlers from the great fishing ports of Devon and Cornwall and Scotland and the east coast of England meant that increasing numbers of high-powered fishing skippers, almost entirely from Britain, were demanding that they be allowed to use Howth, and by the 1860s it had been designated a “Fishing Station”.

Howth Harbour in the 1870s, when it had become a “Fishing Station”

Much the same thing happened at Dunmore East, which was initially the packet boat port for Waterford, and the local fishermen weren’t really allowed into it at all. But then the advent of steamships meant the packet boats could go straight up to Waterford itself, and after an interval lying idle, Dunmore East also became a Fishing Station. But it was only because nobody else further up the pecking order had a use for it – in those days, fishermen were expected to fend for themselves.

So for thirty years and more, Howth was almost totally devoted to fishing, but in 1875 the famous Judge Boyd – he is referenced in Ulysses – took a lease on the harbourside Howth House which had originally been built as a residence for John Rennie, the engineer building the harbour. The Judge was well got, as his main house was in Merrion Square – it’s now the French Embassy – but as he was something of a maverick, he decided that he’d pursue his sport of sailing through Howth rather than Kingstown.

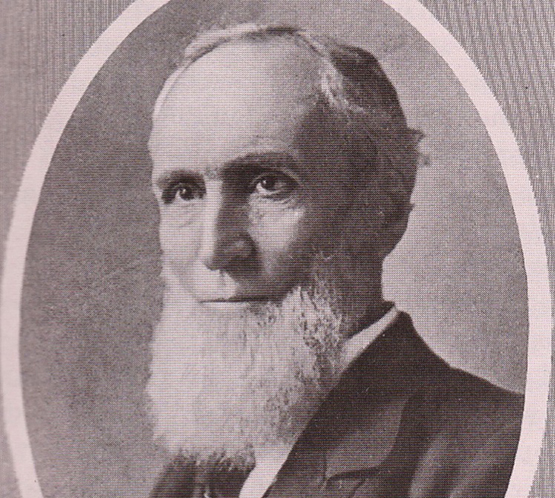

Judge Boyd was such a noted Dublin character that he was referenced in Joyce’s Ulysses

Thanks to Judge Boyd’s influence, Howth had a government dredger almost permanently on station from 1888 onwards. And for those who would seek further cultural references, the Yeats family lived in the house on the foreshore just to the left of the fishing boat from 1880 to 1882

A maverick he may have been, but he had influence in high places, and when the silting of Howth became even worse in the 1880s, hampering the seasonal activities of the travelling fishing fleets, the Judge saw to it that Howth got its own government dredger as an almost permanent feature.

The trouble is, the fishing was too successful – the herring were fished almost to extinction. By the 1890s, fleets visiting Howth were declining rapidly, but this in turn facilitated the development of the local sailing club, founded mostly by Judge Boyd’s sons in 1895.

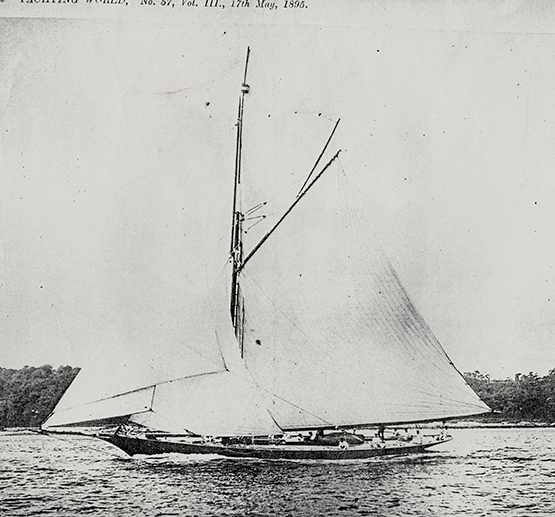

However, the old Judge had lost none of his sparkle, for in 1892 he had bought the supposedly out-classed Fife 70-footer Thalia from the Clyde, and proceeded to win races left right and centre with her. Often he helmed her himself, but if he felt like a rest, the talented professional skipper who came with the boat was Owen Bissett, who stayed on in Ireland with such commitment that today one of Howth’s most able sailors, Ross McDonald, is Owen Bissett’s great-great grandson.

Judge Boyd’s Thalia racing in the Clyde – in Clyde Fortnight 1897 she won 140 pounds in prize money, the third highest in the regatta. Though he raced the boat himself, Judge Boyd also had a professional skipper in Owen Bissett, great great grandfather of today’s successful Howth skipper Ross McDonald

And if you wonder how the Judge managed to keep a large engineless yacht in little Howth Harbour, a yacht whose overall length from mainboom end to bowsprit end was well over a hundred feet, the answer is he treated Howth Harbour as if it was his private marina. After all, it was he who ensured it was dredged, so hadn’t he every right to keep Thalia in a very handy berth inside the nib on the West Pier? And if he happened to omit to retract Thalia’s long bowsprit which protruded well beyond the end of the nib, then heaven help any fishing skipper whose ancient craft managed to get fouled up in this exquisite piece of classic yacht equipment.

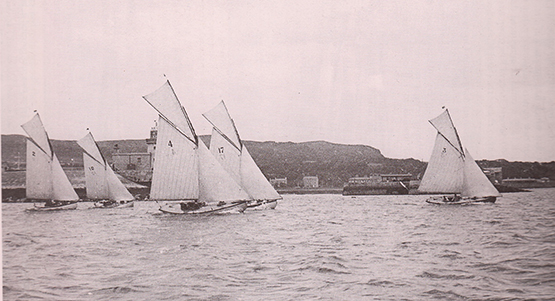

Regatta day at Howth, and Thalia in her berth inside the nib on the West Pier

The perfect private berth – Thalia at the West Pier in Howth around 1900

It’s difficult to escape the feeling that the Judge’s four sons thought the old man was maybe a bit over the top, for in their new Howth Sailing Club they promoted the notion that “Small is Beautiful”. When the oldest brother Herbert designed the new one design class for Howth in the Autumn of 1897, the resulting Howth 17s were of very modest proportions, just 22ft 6ins in overall length.

In time, the mighty Thalia ceased to be a feature of Howth Harbour. She was of such a size that the easiest way to lay her up was a winter berth afloat in the Grand Canal basin in Dublin. But as she had been built on steel frames with copper fastenings, she was virtually on fire with electrolysis, and her days were short – by 1910 she had gone.

A much more modest proposition – the handy little Howth 17s were introduced in 1898, and they hope to have 18 boats racing this summer

From time to time, the Howth 17s add new boats – this is Erica and Isobel joining the fleet in 1988

The joys of classic yacht ownership…..Pat Heydon working in early March on the re-caulking of Gladys (built 1907), which he co-owns with Eddie Ferris and Ian Byrne. Photo: W M Nixon

But the Howth 17s plough steadily on 118 years later, thanks to a sort of group scheme of mutual help when a boat needs serious work done, with longtime owner Ian Malcolm as the multi-talented core of a sort of men and women’s shed movement with a maritime purpose. The purpose is to get in as much racing as they can, with as many boats as humanly possible. This season they’ll have 18 of them sailing, while a classic boat festival at Howth in early August has already roped in Mermaid Week, and they and the Seventeens will be more than happy to welcome other long-established wooden craft.

As for Howth generally, the inevitable conflict between the needs of fishing craft and the needs of recreational boating were more or less resolved back in 1982, when the recreationals were moved into the eastern part of the harbour with its marina and - in time - a completely new clubhouse, while the western section became a state-of-the-art fish dock with synchro-lift and all the trimmings.

It was a case of good fences making good neighbours, and maybe the harbour users of Howth became too contented, for the powers-that-be seemed to forget that in a harbour set beside a sandy channel through which the tide can flow with some vigour, routine maintenance includes regular dredging.

In The Netherlands, arguably the best-run maritime nation in the world, every harbour is dredged as a matter of routine every four to five years, regardless of whether or not there has been significant silting. It’s just done, and that’s how it is – it’s the Dutch way.

But in Ireland, it seems we have to chivvy the authorities to do what should be a matter of routine, and ultimately it all seems to come back to the door of the Office of Public Works, which despite its name seems to think that it’s activities should be carried out in as private a way as possible. Maybe it should be re-named the Office of Good Works By Stealth, for the word is that Howth is going to be dredged, and it might well be sooner than later.

Meanwhile, the Department of Agriculture & Fisheries have been quietly beavering away providing the small boat fishermen with their own rather splendid pontoon. It’s an extremely fine bit of work, but so far as we know, it is only recently that the notice has gone up telling us what it’s all about.

It’s coming to a harbour near you…….the notice of the new facility was erected without any fanfare...

...and for the time being there’s no news of when the new pontoon will be officially opened

As for actually getting the use of it, the situation is now a bit reminiscent of the 1840s. There’s this really classy and useful bit of infrastructure, just as there was once the unused Howth Harbour back in the 1840s. But nobody is as yet allowed near it. The smaller fishing craft still raft up outside each other, and their crews still have to clamber up the quayside.

There’s probably a perfectly good reason why the new pontoon has not yet opened for business. But as our email enquiry to the Department has gone unanswered, we can only assume that until a new Government is formed and there’s a fully-accredited new Minister ready to sweep out in the limo to perform the opening ceremony with all the attendant pomp and kudos, then this lovely pontoon will continue to float serenely on, just like the Sleeping Beauty.

While Howth’s new small fishing craft pontoon awaits its official opening, its future users continue to raft up alongside each other at the quay. Photo: W M Nixon