Displaying items by tag: Mayflower

Transatlantic Un-Crewed Ship? Why Not Ocean-Crossing Unmanned Nuclear Submarines?

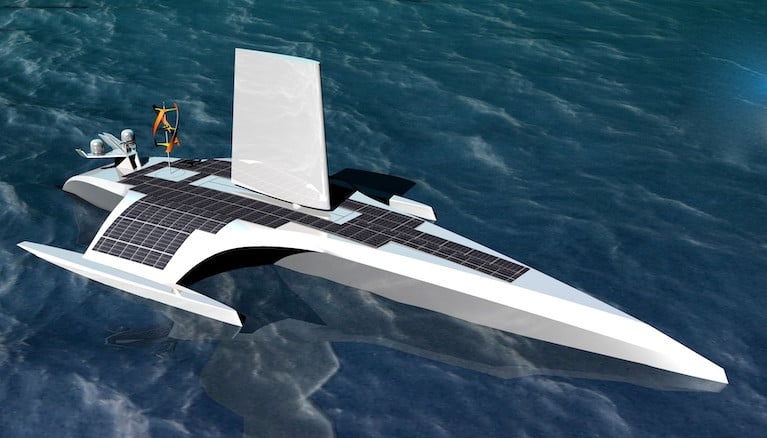

Today (Wednesday) in Plymouth in England, the Mayflower Autonomous Ship is expected to have her official launch, though the word is she has been test floated in advance. If that's the case, it was a prudent move, for although un-manned ships using Artificial Intelligence and other technologies have been ideas in the making for some time, this particular 15-metre trimaran – called Mayflower in honour of the 400th Anniversary of the Pilgrim Fathers' voyage in the original Mayflower from Plymouth in Devon to what became Plymouth in Massachusetts – is really pushing the envelope in just about every direction, as she will be reliant on AI, solar power and the auxiliary support of a wing sail to get her alone across the Atlantic.

Built in Gdansk in Poland for a partnership which includes ProMare and IBM, this 50-footer was originally supposed to have been launched at the beginning of the summer and to be starting her voyage around now, after extensive sea trials. But the pandemic has delayed everything, and the pioneering Transatlantic voyage is currently planned for early next summer after trialling through the winter.

Building the Mayflower Autonomous Ship in Gdansk

This may be no bad thing for the promoters of the project, as the western side of the North Atlantic at the moment is experiencing the most active tropical storm and hurricane-generating conditions ever recorded. Doubtless, we'll be feeling the effects of that in Ireland in due course, but right now the idea of sending a slip of a thing directly to America ultimately relying on solar power on a northern route re-tracing the original Mayflower's course of 1620 might well prove to be a test too far.

Ghost from the past. The two Mayflowers: the original took 66 days to get across the Atlantic in 1620

Ghost from the past. The two Mayflowers: the original took 66 days to get across the Atlantic in 1620

In fact, if you're contemplating an east-west Transatlantic voyage across the direct route on the North Atlantic in the next few weeks, for your comfort and safety we'd recommend hopping aboard a west-bound nuclear submarine. Of course, this is the negation of using solar power. But as this department of Afloat.ie has been in cahoots for a long time with that secret society which believes we're ultimately going to have to rely on nuclear power to save the planet, the entire idea seems utterly logical, and going underwater makes sense.

For it's on the interface between sea and air that boats and ships get battered about. Go silent, go deep, go smooth. Back in the day when NATO saw large fleets exercising in harmony, other navies noticed that around mid-day there seemed to be a slackening of activity among French submarines. Between 1230 hrs and 1430 hrs, you wouldn't hear a word from them at all. It seems they all gently descended to their own favoured smooth spots on the seabed, and there they sat in order to enjoy a proper French lunch – wine and all – totally undisturbed.

French Nuclear submarine of the Shortfin Barracuda Class. A descent to the peace of the seabed for an undisturbed lunch was, as they say in the Michelin Guide, "well worth the detour".

French Nuclear submarine of the Shortfin Barracuda Class. A descent to the peace of the seabed for an undisturbed lunch was, as they say in the Michelin Guide, "well worth the detour".

So maybe if we want to send unmanned "ships" reliably across the Atlantic, we should be thinking under-water well below those bumpy waves, and use crew-less nuclear subs. The technology would be mind-boggling. But apparently some of the computing power being deployed for the Mayflower Autonomous Ship was originally devised to predict risks in international banking, and just look how successful that has been over the years…….

If Your Port’s Name is Attached to a Sailing Event, Make Sure to Keep That Link Alive…

Some sailing events capture the popular imagination, while others – for some reason – simply pass by relatively unheeded. Either way, there’s no doubting that the 628-mile Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race is in the former category, with its crazy Christmas-time start witnessed by as many as 600,000 people, watching the inevitable flotilla of over-the-top SuperMaxis weaving their way out of the superb harbour at the head of an exceptionally varied and historic fleet.

It was going to be special in this year of all years, for 75 years is a long time in terms of Euro-centric Australian history. Of course, there were people in Australia for tens of thousands of years before the Europeans arrived. But like the early pre-Spanish discoverers of the Canary Islands, those First Australians who did manage to get safely ashore – for many didn’t make it – gradually abandoned any thought of seafaring as they worked out ways of making a living entirely on land from this very strange place they’d stumbled upon.

The big boats get away from the Sydney haze at the start on Thursday. Photo: Rolex/Kurt Arrigo

The big boats get away from the Sydney haze at the start on Thursday. Photo: Rolex/Kurt Arrigo

But for the new Australians from Europe, seafaring with its communication to the outside world was essential. Yet their distance from that world meant they developed their own ways of doing things, with the betting-mad Sydney Harbour 18-footers the ultimate sailing expression of the sports-oriented Australian way of life.

This year, the Sydney-Hobart has taken on added significance, for since August, Australia has been fighting a growing – and sometimes tragically fatal - battle with bush fires. The Lucky Country has been out of some of its luck, and it’s arguable that this loss of luck has been partly self-inflicted. But no country in the world can claim innocence in the causes of climate change, yet it’s Australia’s misfortune that the bush fires after years of drought should so markedly impinge on the Australian way of life, with its outdoor emphasis.

The Sydney-Hobart Race is a chance to show that life goes on, albeit in a wiser frame of mind. All it needed on December 26th 2019 was a decent onshore breeze to restore Sydney Harbour to its clear and sunny self, and a fleet which acknowledged that times aren’t quite normal, but life must go on.

The SuperMaxis heading into open water on Thursday – the size of the spectator fleet, plus tens of thousands of watchers ashore, spoke volumes for how much the successful staging of the 75th Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race meant to Australians in these challenging times. Photo: Rolex/Kurt Arrigo

The SuperMaxis heading into open water on Thursday – the size of the spectator fleet, plus tens of thousands of watchers ashore, spoke volumes for how much the successful staging of the 75th Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race meant to Australians in these challenging times. Photo: Rolex/Kurt Arrigo

And it certainly is a life-affirming event, one of sailing’s great spectacles, yet one in which every boat in the fleet from 30 footers to 100 footers feels equally involved. Having been inaugurated in 1945 under the inspiration of that remarkable offshore racing pioneer John Illingworth, it soon seemed the most natural thing in the world to race from Sydney to Hobart, for an annual cruise-in-company along the same route was a Christmas tradition at the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia.

Today, Sydney-Hobart as a brand name has real muscle, and while Sydney has always basked in its association with the race’s start, it took the more conservative Hobart rather longer to realize that this sporting special gave them a USP in the Tasmania-promotion stakes for tourism.

Hobart in Tasmania – it’s the same latitude as Bordeaux in France

Hobart in Tasmania – it’s the same latitude as Bordeaux in France

In fact, interest is at an all-time high, for last year for the first time a Tasmanian boat was the overall winner, Philip Turner’s RP66 Alive. It’s as though a Wicklow boat had won the Round Ireland Race…… And these days, those who had thought Tasmania was a remote and windy island somewhere down towards the Antarctic are now aware that Hobart in the Southern Hemisphere is on the same latitude as Bordeaux in the Northern Hemisphere, and it’s a charming and scenically stunning place with its own remarkable classic yacht tradition.

The Tasmanian RP 66 Alive weathering the famous Organ Pipes in the approaches to Hobart, on her way to the overall win in the 2018 Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race. Photo: Studio Borlenghi/Rolex

The Tasmanian RP 66 Alive weathering the famous Organ Pipes in the approaches to Hobart, on her way to the overall win in the 2018 Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race. Photo: Studio Borlenghi/Rolex

Thus the message is that if you’ve got your port associated with a great sailing event which has popular interest, for heaven’s sake do everything you can to nurture the relationship. In following the Sydney-Hobart Race’s fascinating progress with its often extraordinary yet time-honoured finish totally identified with Hobart, it’s a reminder that just a month ago, the world of offshore racing – indeed the world of sailing globally – was agog at the news that the biennial Fastnet Races of 2021 and 2023 would not finish at Plymouth in Devon - as the race had done since its inauguration in 1925 - but instead would finish in Cherbourg, where the local authorities were prepared to be lavish with their preparations and welcome.

The people of Plymouth must think the fates have got it in for them. The historic harbour, associated with the swashbuckling if sometimes very questionable wealth-enhancing seafaring deeds of the likes of Drake and Raleigh and Hawkins, has been seeing its more modern maritime links greedily challenged by other ports.

As Shakespeare observed in another context in the time of those energetic opportunists: “When sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalions”. For Plymouth, it was only starting when it was announced back in May that an alternative OSTAR (the original single-handed Transatlantic Race first staged from Plymouth’s Royal Western YC in 1960) was going to have a highly-funded re-birth from Brest in France.

The Port of Plymouth, which has hosted the finish of every Fastnet Race since 1925. But for 2021, the finish will be in Cherbourg

The Port of Plymouth, which has hosted the finish of every Fastnet Race since 1925. But for 2021, the finish will be in Cherbourg

That announcement didn’t come from Plymouth. It emanated from OC Sport, who have rights in the race and are based in Cowes, but have been majority French-owned since 2014. Meanwhile, Plymouth is going ahead with its own 60th Anniversary OSTAR (Original Single-Handed Race) on 10th May.

For the mega-funded hyper-publicised French super-multihulls, the offering from Brest has obvious appeal. But the historical claims of Plymouth are likewise gaining their adherents, and as entries don’t close until 16th March 2020, the evolving story of the two races is continuing.

Then in late November, with just ten days to go until December’s Paris Boat Show with its potential to give significant upcoming events a fresh buzz of publicity, it was announced that the RORC Rolex Fastnet Races of 2021 and 2023 would not be finishing in Plymouth - as the race has done since it was founded in 1925 – but instead, in a course 90 miles longer, the finish would be in facility-filled money-waving Cherbourg in France.

The reactions to this have been spread right across the entire spectrum from complete disapproval to enthusiastic support, and even now it’s still simmering.

At the apparently rather sparsely attended but online-streamed press conference in RORC HQ in London, the top honchos did reveal that for the Centenary Fastnet Race in 2025, they might consider returning to Plymouth if berthing facilities has been markedly improved.

In the circumstances, it sounded slightly patronizing with an unpleasant whiff of the wheeler-dealing about it. But we can soften their cough by pointing out that if they really want a truly authentic Centenary Fastnet Race in 2025, then they’ll have to abandon the Cowes starting line, and instead start the fleet eastward out of the Solent from the Royal Victoria Yacht Club in Ryde. Back in 1925, the big clubs at Cowes declined to get involved in this crazy new venture. But once it was clear that it was established and would happen again, it was a case of Hello Cowes, Goodbye Ryde…….

Wherever the Fastnet Race starts or finishes, it will still have to go round Ireland’s most famous rock. This is the American former Volvo 70 Wizard (David & Peter Askew), winner of World Sailing’s “Boat of the Year 2019” title, at the Fastnet Rock on her way to winning the Rolex Fastnet race 2019. Photo: Rolex

Wherever the Fastnet Race starts or finishes, it will still have to go round Ireland’s most famous rock. This is the American former Volvo 70 Wizard (David & Peter Askew), winner of World Sailing’s “Boat of the Year 2019” title, at the Fastnet Rock on her way to winning the Rolex Fastnet race 2019. Photo: Rolex

No matter what they do, Ireland’s impregnable Fastnet Rock remains immovably at the heart of it all. It is simply The Fastnet Race – full stop. But back in Plymouth, yet another historical challenge to their cherished maritime perception of themselves arose at the end of November. For they’d been thinking that, regardless of what might happen to the OSTAR and the Fastnet Race, the really big deal in their maritime history is their link to the Pilgrim Fathers sailing in the Mayflower from Plymouth to America in 1620.

Now there’s an anniversary to conjure with. 400 years to be celebrated in Plymouth in 2020 for something which has pure gold historical importance. But the people of Harwich on England’s East Coast say that Plymouth’s claims to the Mayflower story are only incidental. The ship began her voyage from the East Coast, they say, and only called briefly at Plymouth while heading west.

To underline their case, they’ve spent 2019 restoring the house in Harwich which was the home of Christopher Jones, Captain of the Mayflower, and in 2020 they look forward to greeting thousands of American visitors to Mayflower’s most tangible and authentic link.

And to the west of Plymouth, the people of the fishing port of Newlyn in Cornwall are also claiming that the Mayflower actually stopped there - albeit briefly – before the real beginning of the Transatlantic voyage, so that’s where the American tourists should be splashing their dollars.

Quite so. It would be time for the people of Plymouth to send for Francis Drake and his more ruthless shipmates to sort this out were it not for one indisputable geographic and historical fact. The place where the Pilgrim Fathers first landed in America in December 1620 is now known as Plymouh Rock. It is in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Harwich? Newlyn? Fuggedaboudit……..

An inescapable fact of history and geography – Mayflower II berthed at Plymouth, Massachusetts.

An inescapable fact of history and geography – Mayflower II berthed at Plymouth, Massachusetts.

Meanwhile, Hobart and Tasmania have literally shaken off their links with a dismal penal colonial, past, and the place is re-born as a destination for the discerning, with a pleasant climate, fantastic scenery, and some great sailing people who can count winning the Sydney-Hobart race among their achievements. There’s no way they’re going to allow that particular link to be broken.

Mayflower 'Autonomous Ship' Are Planning A Crowdfunding Launch

Members of the public will be able to see their name etched into history when ambitious plans to build a multi-million pound robot boat to mark the 400th anniversary of the sailing of the Mayflower out of Plymouth take another step forward next month.

The team behind the Mayflower Autonomous Ship are planning a Crowdfunding launch which will offer, among many other rewards, the chance to put individual names on the side of the ship when it is built.

It will be the 21st Century version of the Mayflower and be able to sail without crew from Plymouth UK to Plymouth, USA in 2020 on the 400th anniversary of the first sailing.

Last week organisers received the support of the Ambassador of the United States of America Matthew Barzun at a special reception at the Embassy in London to celebrate the transatlantic relationship.

But in order to get the design from blueprint to boatyard, organisers need to raise £300,000 for the crucial next design and development stage which will include robust wave tank scale-model testing.

Everyone is being offered the chance to get their name written into history as ‘new pilgrims' by buying a reward that will literally make their mark on the project. For £20 you can put your name on the boat; for £50 you can put your family's name on it and for £35 you can put two names and a significant date.

Larger rewards will include invitations to VIP events, invitations to the launch, exclusive opportunities and other offers.

"So far we have the plans, the passion, the potential and now all we need is to get it to production," explains Patrick Dowsett, who spent 30 years in the Royal Navy, including time as a commander, in charge of HMS Northumberland.

"It is ground-breaking in so many ways and will put Plymouth on the global map for marine science excellence. We are offering everyone a chance to get involved in this incredible Devon project.

"This first stage will nail down the planning, the testing, the project development and the modelling to enable us to start the build of the real thing in 2018."

The launch of the Mayflower Autonomous Ship out of Plymouth UK as the flagship of the Mayflower 400 celebrations will cement the city's reputation as a global centre of marine excellence and a marine science hub.

The Mayflower Autonomous Ship (MAS) will be the first vessel of its kind to sail without captain or crew across the Atlantic and be able to conduct scientific research around the world.

With driverless cars already on the horizon and the air industry using computers to fly planes, MAS could lead the way to changing the way the shipping industry works.

When launched, the MAS could be controlled by a computer, or by a captain sitting behind a virtual bridge onshore. It would sail out of Plymouth via remote control and then switch to autonomous control once out at sea.

It will be solar powered, with cutting edge battery and renewable energy capture, travelling to inhospitable parts of the world to conduct scientific research and collect data. Onboard there will be unmanned aerial vehicles plus life rafts so that it can respond to a distress call from other mariners, and be first on the scene and render assistance.

The MAS will be built in Plymouth and the South West. The team behind the project, a collaboration between Plymouth submarine builder MSubs, Plymouth University and charitable marine research foundation Promare, is looking for suitable locations.

Historic Mayflower II Replica Pilgrim Ship Set for Restoration

#mayflowerII – The American–based historic replica ship Mayflower II arrived at Mystic Seaport on Sunday for a restoration at the southeastern Connecticut museum's Henry B. duPont Preservation Shipyard.

The original 110 ft. overall Mayflower was the 15th century ship that transported mostly English Puritans, known today as the Pilgrims, from Plymouth, England to the New World.

There were 102 passengers and the crew on the Dutch Cargo class ship is estimated to be approximately 30 but the exact number is unknown.

The ship that first sailed in 1609 plied many routes but her most famous was from Southampton to America.

This voyage has become an iconic story in some of the earliest annals of American history, with its story of death and of survival in the harsh New World winter environment.

Restoration work will begin this month, honouring the Mayflower II's original construction and using traditional methods with the goal of restoring the ship to her original state when she arrived to Plymouth in 1957.