Displaying items by tag: Regatta

Cork Week and How You Can Win

How you can win at Cork Week

How you can win at Cork Week

with more than a little help from local expert Eddie English [pictured left] – Cork Week 2004 (reprinted from Afloat July 2004). For all the up to date information and news on Cork Week click here.

Eddie English stands high on Cobh’s historic waterfront and looks out across Cork Harbour, south towards Roche’s Point Lighthouse and the entrance to the natural sanctuary. Immediately below, a huge Brittany Ferries ship heads slowly out to sea; it’s not even close in size to a previous visitor to the former Queenstown, but then again, the RMS Titanic belonged to a different era.

To his left, the inshore waters north of the Whitegate oil refinery hide the channel to East Ferry where the Marlogue Inn stands over its marina and just opposite, the legendary Murphs on the mainland shore.

On his right, the channel between Spike and Haulbowline Islands and Cobh is the main shipping route for the Port of Cork for ferries, commercial shipping and the Irish Naval Service base.

But it’s the view straight out to sea that confirms one of the magic ingredients that have made Cork Week an international regatta of worldwide repute: vast tracts of open, unobstructed water and all within easy reach of the shoreside facilities of the hosts at the Royal Cork Marina at Crosshaven.

When it comes to local knowledge, few are as expert as English. Not only is he chairman of the event's racing committee, not only does he run a long-established sailing school in the harbour, but when you are offered an insight from someone who takes his dog for a walk on notorious mud banks at low water springs, they tend to be nuggets of the golden variety.

Left: Sigma 33s negotiate Roche’s Point

"The harbour course is the key to Cork Week," says English. "It's the decider where the event is won or lost and has the most variables involved." So this, then, is the Eddie English step-by-step guide to gaining an edge for that course, plus the coastal, wind/leeward and Olympic-type courses at Cork Week 2004.

Harbour Race

Above all, be conservative at the start of the Harbour Race if the tide is with you on the start off Weaver's Point. There can be two knots of tide here typically and an OCS in any fleet represents the end of the story with recovery improbable. Ideally, a short tour of the harbour during the weekend registration stage of Cork Week will pay dividends. If you can, borrow a RIB and take the tour at low-water.

Two marks form part of this course outside the harbour and rounding order will depend on wind-direction on the day. The first is off Ringabella to the south-west shore heading towards Kinsale. If there’s a flood tide, hug the shore. In fact, if the breeze is SW, go right, even in an ebb.

The second is off Trabolgan, east of Roche's Point. Crucially, beware of the strength of tide when traversing the channel across the harbour entrance. Don't just rely on the GPS – plot the tidal vectors to find the true course to steer. Once to the east of Roche's Point, there’s negligible tide and often a tide line can be observed.

This course then takes the fleet into the harbour but beware when entering on the east side of the Harbour mouth – the Cow and Calf rocks are extensions of Roche's Point up to one cable off the shore.

Above: Hugging the shoreline for a tactical advantage

Most races will come into a buoy east of Cobh, making this a long leg in, but offer plenty of hazards on a falling tide. After the Cow and Calf, it’s possible to dodge into White Bay but be wary of rocks and shallows on the south end of the bay close to Roche's Point.

The Dog's Nose promontory is next and it’s possible to cut into the area north of here though close inshore it shallows and the Black Rock is marked by a perch as the main hazard.

Bear in mind the sailing instructions that require clearance of 50 metres off the oil refinery jetty at all times. A listening watch on VHF Ch. 12 is useful for avoiding shipping.

Above: The fleet at anchor – everyone’s gone to the pub...

Once past the refinery jetty, the tide running north-east/south-west for the East Ferry channel can suck you in or push you out.

The alternative to the eastern shore approach is to hug the western shore and involves rock-hopping from Ringabella in past Weaver's Point. An option is to duck into the Owenbue River at Crosshaven – the tide ebbs here up to 30–40 minutes before HW Cobh.

North of here, the Curlane Bank, south of Spike Island, offers an option but beware of shallows. The area south-east of Spike is littered with rocks and, in particular, off the eastern end is a large rock marked by a perch.

The Spit Bank is the biggest in the harbour and is located from the north end of Spike from the lighthouse to the corner off Haulbowline. On very low spring tides, football is played on this bank. The key here is: go as close as you dare. The bank is mostly mud except for ‘The Seven Stones’ aka The Ballast Rocks located approximately two cables east south-east of the No. 20 (Port) Buoy.

Having made the turn for the final approach to the Cobh rounding buoy, one of the showcase marks in the entire event set beneath the picturesque back-drop of the town, this leg from ‘Cuskinny Turn’ offers several options in tide. With the tide is a straight-forward matter of choosing the deepest water so check the charts. Usually, the north shore offers no significant gains. Keep a sharp watch for the passenger ferries running from Cobh to Spike and Haulbowline Islands.

From Cobh, the Harbour Race will have a new finishing line in 2004, moving to the No. 7 (starboard) buoy south of the refinery.

Coastal Course

Going west from the start in a south-westerly or filling sea-breeze, taking the right-handside of the course, pays off, thanks to lifts off the shore. Use the bays to get out of the tide, with the exception of the first bay after Robert's Head/Daunt buoy – it’s called Rocky Bay and it is!

The tide here follows a south-west/north-east direction in line with the heads with a one-knot maximum. Keep the harbour entrance strategy from the previous course notes in mind too.

For 2004, the former south-east mark located approximately three miles east of Roche's Point has been renamed Moonduster as a tribute to the late Denis Doyle and his legendary 51-foot yacht that is synonymous with Cork.

All Courses

The Olympic and windward/leeward are located outside the harbour so allow plenty of time to get afloat – some courses could take you up to an hour to reach as the number of yachts leaving Crosshaven at one time can mean congestion. The furthest course is three miles south-east of Roche's Point which in turn is two miles from Crosshaven. Don't assume the Race Officers will wait – best advice is to follow the professionals' example and leave early to be at sea on time with an opportunity to practice a few crew drills.

These courses usually have no significant tidal factors as most are located outside the harbour and beyond the main entrance tide line. More importantly, if a sea breeze builds, this will be of more use to you.

If a sea-breeze applies, it generally tends to build from around 11am, peaks at 3pm and is gone by 6pm. It will usually begin in the south/south-east provided the gradient doesn't block it. It tends to veer throughout the day until it comes from the SSW to SW – always moving right as the day progresses. Be vigilant to spot it building as it applies to all courses.

Cork Week, How Rocketships work

Jargon – How the Cork Week Rocketships Work

Sailing fast is all about converting the wind’s energy into boat speed and these big ocean racers generate more horsepower and speed for their size than any single-hull craft that has ever sailed the seven seas.

When the wind blows over 20 knots they leave pursuing powerboats wallowing in their wake. Photographers have to resort to helicopters.

The secret to the success of these high-tech speedsters is their weight-saving, super-strong, carbon fibre construction and their radical underwater design.

Gone are the keel and rudder combinations of conventional sailboats where the shape and weight of the keel counteracts the heeling effect of the wind and helps prevent the boat making leeway (slipping sideways).

In place of the keel is a slender strut with a nine-ton ballast bulb at its tip. Swung out (canted) sideways under the boat by a hydraulic ram, the bulb provides extra stability, standing the boat up straighter and making the sails more efficient.

The twin rudders, one ahead of the strut and one behind it, perform a double duty. They provide the foil shape and area to minimise leeway while also improving maneuverability.

Tacking calls for no more than the touch of a button to swing the keel into a new direction.

Disney and Plattner, the CEO of Germany’s SAP software empire, were fellow competitors in a previous class of lightweight 75-foot ocean racers, worked together to create the new class.

"To have a bunch of boats where we can go out and actually have boat races instead of designer races seems to me to be really good idea,‰ Disney said. „That's what I hope for with this project – that it will attract people who want to go racing on the same terms. Not that we all don't like to go a little bit faster than the next guy, but it's a lot more fun when it’s a boat race."

Cork Week Uncovered: Who Will Be There

Cork Week Uncovered: Who Will Be There

From Afloat, July 2006

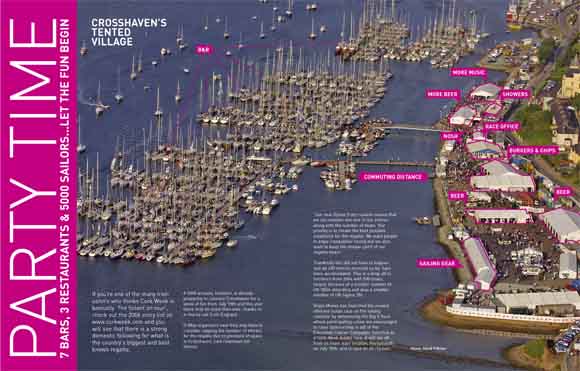

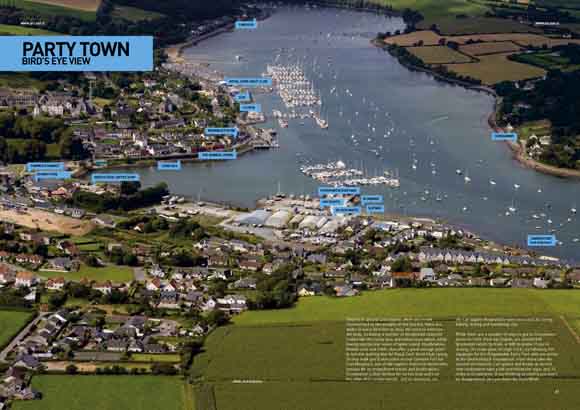

Cork Week's not all about rubbing shoulders with serious money but, having that said, there will be more millionaires on the banks of the Currabinny river between July 10 and 16 than sails in the harbour. Crosshaven will teem with sailors and supporters for a festival of sailing that’s more like Galway Races on water than a regular sailing regatta.

And that's the reason it’s become so popular with foreigners, attracting 80 per cent of its competitors from overseas.

Pyewacket and Morning Glory may be the big glamour boats but the entry list has 499 other boats as well, the bulk of which are from the UK visitors. Up to 7,000 competitors will take to the water each morning, bringing an estimated 10 million euro into the local economy. That may be small beer to the likes of Roy Disney but in sporting terms it's like having the commercial return of an international rugby fixture in an otherwise sleepy fishing village.

Seven bars, three restaurants, 50 bands, 400 performers and 180 hours of entertainment are ready to serve competitors from as far away as the US, Hong Kong, Australia, France, Germany and Belgium along with a huge representation from England, Scotland and Wales.

On the water the fleets are split over eight different courses according to size of boat. Sailors are categorised too and part of the charm of the race week is that the majority of racing classes prohibit sailing professionals as crew.

Cork Week and the Roy Disney Connection

Cork Week and Roy Disney

By David O'Brien

Reproduced from Afloat Magazine, July 2006.

If sailing faster than the wind sounds like something out a Disney fantasy, then that’s because it was. And now, as Roy Disney - the 73-year-old nephew of the legendary Walt - prepares to hit the water in Cork today, (July 10) that fantasy has become reality for the first time in Europe.

Disney has temporarily left boardroom battles behind him to pitch his stunning yacht against the competition around Cork harbour. His 86-foot, space-age boat, Pyewacket, was fast tracked across the Atlantic on top of a cargo ship directly from Bermuda just to be here in time for the first race of Cork Week, an Irish regatta with a global reputation for fun and great racing, and one which Disney claims he wouldn’t miss for the world.

Depending on how you look at it, the international regatta circuit that has taken him to St Maarten, Tortola, Antiqua and Bermuda this year is either a logistical nightmare or a gorgeous extravagance.

Whichever it is - and Disney reckons it’s probably a bit of both - it's an infatuation that keeps him burning with enthusiasm when sailing is at the top of the agenda. For 50 years he has followed a fantasy to see his boats go faster than all the others - and now he’s living that dream.

This year he has come in for international acclaim, not for his company's movie work, but in yachting circles, for bringing racing to a new level by creating the Maxi big Z86, a yacht that’s capable of sailing faster than the speed of the wind.

Already nicknamed 'the rocketship' by jealous competitors, Pyewacket is one of two such designs built to demolish the world's sailing speed records for monohull boats.

And if they’re untouchable when it comes to straight line racing, the new designs are proving equally superior in around-the-buoys events too. At Antigua Race Week this spring, they left their competition behind in showers of spray and they threaten to repeat that feat at Cork today.

The secret to the success of these high-tech speedsters is a weight-saving, super-strong, carbon fibre construction and radical underwater keel designs.

“Sailing in just 3.5 knots of true wind, we were slipping effortlessly through the water at almost three times that speed during the race to Bermuda. There are not many times when we can't sail faster than the wind,” Disney enthuses. “If we get 15 knots winds, we can sail at 20 knots easily thanks to this design.”

But all these things come at a price and no one is forthcoming - not event the two billionaires owners - on the total development costs thus far.

Ted Heath once said that sailing was like standing in the shower tearing up £5 notes. It's an oft-used quotation but it still draws a giggle from Disney who adds "yeah...and most of the time it’s in the dark too!"

According to insiders, sailing campaigns at this cutting-edge level cost up to $5m a year - and this excludes the capital cost of the boat.

"It's like Rockefeller said: "If you have to ask how much it costs, you can't afford it. And I can afford it," says Disney.

He readily admits that some people ask him if he's mad, to which he replies "We're all crazy, so why not have some fun? When it stops being fun, then that will be my last race."

Joking aside, Disney reckons that he’s now sailing at a level where he can't afford to do it badly.

"I need skilled people to crew this yacht, he explains. “When you sail at 27 knots, the loads involved are huge. I need to sign on the bottom line to have it sailed professionally. Otherwise people could get hurt or lost overboard."

Today's Cork Week race follows Disney's defeat by Hasso Plattner's Morning Glory, Pyewacket's sistership, in a race from Newport, Rhode Island to Bermuda in the last week of June. Plattner, who took a 30-mile lead on Disney in a race the Hollywood giant previously called his own, smashed the elapsed time record previously held by Disney since 2001.

Cork Week therefore represents the first opportunity to avenge this defeat. Royal Cork, not surprisingly, is trying its best to facilitate a pitched battle between the two space-age craft, designing courses that are sure to set the two pitching against one another until the finishing line.

"They could have chosen Cowes or Sardinia to unveil this next generation of racing yacht but they didn't, says Donal McClement of the host yacht club, the Royal Cork. “They chose Cork and that's a big honour for us. McClement has sailed with Disney in previous Cork weeks and will sail again as a local tactician this time.

The fact the world’s big guns are coming to Cork is, of course, a compliment to the organisation for the Crosshaven event, but in Disney’s case it also has something to do with the fact that he’s a member at Royal Cork, and a patron of its junior sailors. He’s had a second home in Ireland - in Kilbrittain in West Cork - for the past 15 years, where he spends up to three months of the year.

Neither Roy's father nor his uncle - the company’s founder, Walt - were sailors, yet they always encouraged his sporting passion for diving and swimming as a teenager.

It's sounds twee to describe Roy’s sailing career as a 'race into paradise' but it’s still an accurate description of the movie-maker's 50-year journey from weekend family sailor of the Fifties to globe-trotting regatta racer of the new millennium.

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, aged just 16, he flew a prototype aircraft - with the full support of his family. It was the unrestrained joy of playing tag in the clouds with like-minded Californian surfer kids that gave him a life-long love of freedom, and speed.

It's more than likely, he concludes, that this later translated into a love of the sea, a passion he was able to share with wife Patty and four young children on weekend trips.

That buzz still drives him on but as his business pressures have increased over the years, the Disney director, listed by Forbes as the 552nd richest man in the world, finds it increasingly difficult to make a complete break from the office.

The introduction of the on-board satellite phone has, ironically, not helped matters, leading instead to a further diminution of his precious freedom.

On more than one occasion on Pacific yacht races he has been interrupted - a thousand miles from land - by the Disney corporation who want him back for a meeting

"Sorry you can’t have me, I'm half way to Honolou," he recalls telling executives who were insisting on his return recently.

As a nephew of Walt, he worked at Mouse Factory for 24 years as a film editor, writer and producer. He left in 1977 but returned seven years later as vice chairman. Credited with rekindling Disney’s love of the animated film - scoring huge success with The Lion King and Little Mermaid - he became chairman of the Feature Animation Division.

However, it hasn’t been his yachting exploits that have raised his public profile so dramatically in the past year. Instead, Disney has become better known - at least among land-lubbers - for his bitter and very public battle with Disney Chairman and CEO Michael Eisner.

On 30 November last year, he resigned from the company, denouncing Eisner for (among other things) the loss of company morale through micro-management, building newer theme parks "on the cheap", changing the company's public image as "always looking for the 'quick buck'", the defection of creative talent to other companies, failure to establish lasting relationships with creative partners and not establishing a management succession plan. Eisner was then stripped of his role as chairman by the Disney board in March - being replaced by Northern Ireland peacemaker George Mitchell - but survived as CEO. It was a half victory for Roy Disney, then, and he has vowed to continue the fight. “ I’m competitive of the water too, you know” he says.

Sailing, he says, releases him from this tension and provides the breaks he needs from the bruising and protracted battle for the right to control Disney’s future.

"Pretty soon you'll be able to read about my success over Eisner,‰ he says, „but in the meantime you might like to have a look at www.savedisney.com.‰ The comment may look innocent enough on paper, but the way in which it is delivered provides an insight into his gritty determination both on and off the water.

"The guy who is running the company for us for the past 20 years is trying to get me out and I'm not taking that lying down," he vows.

Next week the corporate battle stops for Disney. Satellite phone or no, he’ll need to have all hands on deck to fight off the challenge from Morning Glory. If you want to see the technological marvels at first hand, before the circus moves on to Sardinia, head down to Roche's Point and look out over Cork harbour to see an American billionaire sailing faster than the wind. For once in his life, Disney won’t be steering a Mickey Mouse operation.

Cork Week: Georgina Cambell's Gastronomic Guide

Tucking In

Afloat’s waterside restaurant critic Georgina Campbell makes some mouth–watering suggestions for eating ashore after the sailing at Cork Week

Crosshaven – The Moonduster Inn, Lower Road, Crosshaven. Tel 021 483 1610

Jody Drennan’s traditional pub is about five minutes’ walk from the Royal Cork Yacht Club Marina (opposite the Hugh Coveney pier and new lifeboat building) and has a cosy, homely atmosphere with dark wood, open fires and marine artefacts. Menus major in seafood (chowder, crab claws, whole garlic prawns with paprika butter; main courses like black sole on the bone or pan-roasted monkfish with crispy bacon, cherry tomatoes and citrus dressing) but there’s plenty else to choose from: T-bone steak, for example, roast chicken, or a house special burger with crispy bacon, grated cheese and fried egg, served on toasted bread. Dinner: Thursday-Sunday; Lunch: Sunday only.

Carrigaline – Gregory’s Restaurant, Main Street, Carrigaline. Tel 021 437 1512

Gregory Dawson and his partner and restaurant manager Rachelle Harley have been running this bright, comfortable and friendly 40-seater restaurant for a decade now, and it’s still going strong. Main evening menus are (sensibly compact) à la carte, but they also do an early dinner which is great value at E21 (booking essential). Expect classical cooking with an occasional modern twist, based on well-sourced ingredients – fricassée of prawns, perhaps, or rack of lamb with a herb and mustard crust – and you won’t be disappointed. Dinner: Wednesday–Saturday from 6.30; Lunch: Sunday only

Carrigaline – The Bistro, Carrigaline Court Hotel, Carrigaline. Tel: 021 485 2100

This 150-seater has the atmosphere of an independent restaurant rather than hotel dining room. Although large, it’s broken into three spaces, each with its own style – a clever idea that has gone down well – and menus are interesting, based on local produce (seafood is all provided by O’Connells of Cork), and affordable. Good food, efficient service, a pleasant ambience and value for money keep regulars coming back for more. Dinner: Daily; Lunch Sunday only.

Monkstown – The Bosun, The Pier, Monkstown. Tel: 021 484 2172

Nicky and Patricia Moynihan’s highly-regarded bar and restaurant is close to the Cobh car ferry. Seafood takes pride of place on both bar menus (chowder, garlic mussels, real scampi and chips and much else besides,) and in the restaurant (crab claws, sole on the bone, seafood platters) but other specialities include steaks and duckling – and vegetarian options are always available. Relaxed atmosphere, professional service. Bar meals 12–9.30 Monday-Saturday, Sunday to 9; Restaurant 12–2.30 and 6.30–9pm Daily.

Cobh – A favourite destination in Cobh is Robin Hill Restaurant (Lake Road, Rushbrooke; 021 481 1395). A phone call and a taxi are essential as it’s a good way to walk , and up a very steep hill (lovely views though); stylish, great food and heaven for wine buffs. Unfortunately they’re aiming to relocate, but will probably still be here in Cork Week. (Dinner: Wed–Sat, Lunch Sunday only; reservations required). Jacob’s Ladder, at the aptly named WatersEdge Hotel (021 481 5566) is handy and the contemporary restaurant has views across the harbour and a deck where you can make the most of any fine weather. Seafood tops the bill, as usual in this area, but carnivores and vegetarians are not forgotten. (Lunch and Dinner daily; reservations recommended).

Kinsale – Plenty of restaurants to choose from in Kinsale, of course. The special occasion place is Toddies on the Eastern Road (021 477 7769), which is well-located overlooking the harbour; for more informal outings Jean-Marc’s Chow House (021 477 7177) offers oriental cooking with a difference: stylish combinations of Chinese, Thai and Vietnamese cuisines go down a treat with the area’s discerning diners, who enjoy the atmosphere, Jean-Marc’s excellent cooking – and the prices – an average meal is around Euro 27. (Dinner only, daily, from 6.30 in high summer). If you’re in Kinsale at lunchtime head for Fishy Fishy Café (021 477 4453) near St Multose church; this delightful fish shop, delicatessen and restaurant is a mecca for gourmets – but get there early or be prepared to queue (no reservations). Lunch daily 12–3.45.

COPYRIGHT – AFLOAT MAGAZINE 2004

Cork Week 2006 Preview

Preview ~ Cork Week 2006

(reprinted from Afloat June/July 2006)

If you’re one of the many Irish sailors who thinks Cork Week is basically ‘The Solent on tour’, check out the 2006 entry list on www.corkweek.com and you will see that there is a strong domestic sailing following for what is the country's biggest and best known regatta.

A GBR armada, however, is already preparing to colonise Crosshaven for a week of fun from July 15th and this year there may be more than ever, thanks to a charity sail from England.

In May organisers said they may have to consider capping the number of entries for the regatta due to pressure of space in Crosshaven, said Chairman Ian Venner.

“Our new Online Entry system means that we can monitor the size of the entries along with the number of boats. Our priority is to create the best possible conditions for the regatta. We want people to enjoy competitive racing but we also want to keep the unique spirit of our regatta intact.”

Thankfully this did not have to happen and all 450 entries received so far have been accomodated. This is a drop off in numbers from 2004 with 500 boats, largely because of a smaller number of UK SB3s attending and also a smaller number of UK Sigma 38s.

Virgin Money has launched the newest offshore ocean race on the sailing calendar by announcing the Big V Race where participating crews are encouraged to raise sponsorship in aid of the Everyman Cancer Campaign. Selected as a Cork Week feeder race, it will set off from its main start location, Portsmouth, on July 10th, and is open to all classes.

BBC TV presenter, Ben Fogle, who, along with Olympic gold medallist James Cracknell, was narrowly beaten into third place in the Atlantic Rowing Race, has signed up to do the Big V Sail.

Dee Cafferi’s team have also signed up and Dee has agreed to present the prize giving for the race. Details, including race regulations, can be found at http://uk.virginmoney.com/cancer-cover/bigvevents/sail/

Heading up the Irish challenge in what is hoped will be a successful outcome from the Commodore's Cup, Colm Barrington has confirmed that he will be at Cork Week in his new Ker 50, Magic Glove. It will be Gloves first event in Ireland.

UK IRC Class champions Chieftain (IRC SuperZero), Tiamat (IRC0), Mariners Cove (IRC1) and Elusive (IRC3) along with Antix and Checkmate (2nd/3rd IRC2) have all confirmed their entries for Cork Week 2006.

This represents the first major Irish regatta for some of the Irish boats, such as Chieftain and Mariner’s Cove.

Richard Matthews of Oyster Marine, a regular competitor since 1992, has also entered his Oyster 72, Oystercatcher XXVIII.

Class Zero is shaping up to be a great class for racing boats of this size with Benny Kelly also confirming his TP52 Panthera for Crosshaven. On the opposite end of the scale, the SB3 Class should have great racing with about 30/40 boats expected.

Organisers are beaming as the event’s international profile continues to grow with boats from all over the world expected. This year’s regatta has attracted first time entries from the Philippines, South Africa, Italy and Sweden.

Cork Week 2008 Preview

Cork Week 2008 Preview

380 boats and a fleet packed with quality

(reprinted from Afloat June/July 2008)

Markham Nolan previews ACCBank Cork Week that has announced a new Cup for the amateur cruiser-racer

It’s now 30 years since the concept of Cork Week was born. In 1978 Royal Cork started the tradition of a biennial regatta with just 50 enthusiastic boats and a smattering of volunteers. Little did they know what they had started. The regatta gained momentum, and ten years later the club had a major event with a cult sailing following on its hands. Cork Week had arrived.

At that stage, Cork Week was a welcome antidote to the hot-shot racing that pitted the disgruntled amateur against the pro. No pros were allowed at Cork Week, a Corinthian ethic reiterated this year with a new trophy for the amateur cruiser-racer, the Corinthian Cup supplied by the Sisk Group. Boats in IRC Class Zero, in which professional sailors are allowed, are eligible if they have a maximum of one Group 3 classified sailor on board.

However, the pros are out there, in the one-design classes and in the big boats, and part of the experience of something like Cork Week is racing at an event which can still attract top names in yacht racing. Racing against the best is an education, and there’s always the chance that you’ll rub shoulders at the bar, and perhaps learn a trick or two from a friendly pro over a pint.

Since those early days, then, Cork Week has become something of a sailing must-see. It’s a rite of passage, providing milestones every other year by which Irish sailing is measured. Do you remember your first Cork Week? Of course you do. You still tell the stories. The memory will be blurry, sunburnt and caked in salt, but you’ll remember it – for many reasons.

There’s the fact that Crosshaven, geographically, was never meant by God to see this much action. The narrow tidal estuary has overcome its limitations through innovation, expansion and pure can-do moxy to accommodate all-comers. As craft of every conceivable shape and size funnel into the harbour at the end of the racing day, you could practically walk from shore to shore without getting your feet wet, using the moving boats as stepping stones.

There’s the fact that, for plenty of us, this is, undoubtedly, the biggest and best event available.

Until recently, nothing came close to Cork Week for sheer volume, with several acres of canvas hoisted by thousands of competitors every day, and gallons of liquid refreshment sluiced through bodies every evening. It has been Ireland’s yacht racing behemoth for decades, and the numbers, when all is said and done, are mind-boggling. There’s the craic, the unquantifiable charisma that is a factor of place, people and shared experience.

And then there’s the racing. Outside the heads the fleets go their separate ways in the morning, returning to the marina, bar and bandstand together at the end of the day. The middle part of the day is filled with the reason most go to Cork – a mix of courses, conditions, classes and competition that is unsurpassed.

The secret, as always, is in the successful mix of onshore and offshore pleasures. The tent city provides as many memories as do the racecourses, and with 10,000 visitors through the gates in any given year, its status as one of Ireland’s biggest sporting events is assured. Landlubber delights this year include several top music acts, with Paddy Casey and Aslan just two of the big names gracing the tent city in ’08.

But what of the racing at ACC Bank Cork Week, the 2008 edition, which is likely to be as memorable as any other? Entries have already reached a respectable 380, down from the heady, chaotic days of 600 boats and more, but it’s a fleet packed with quality. Again, it’ll be a spectacle like no other at the top end of the ratings, where the big money and the pros live.

For those who enjoy the skyscraper effect of superyachts, as you crane your neck upwards to take in their monstrous rigs, there are a handful of over-60s, including the awesome STP 65 Moneypenny, owned by San Franciscan Jim Schwarz, and the enormous 90-foot Reichel Pugh, Rambler, one of two maxis which featured in last year’s Fastnet Race.

However, it’s the slightly smaller TP52s that have the most potential for high-speed, close quarters cut-and-thrust racing. The six one-design carbon sleds (or as close as dammit to one-design), include Colm Barrington’s Flash Glove. The fleet will line out off Roches Point and those following form will be offering slim odds on Benny Kelly’s Panthera, which has stolen a clutch of victories around England’s south coast already this year.

Ten Farr 45s form another high-performance one-design category within IRC class Zero, as well as, further down the ratings, ten X332s, a dozen Beneteau 31.7s and more than two dozen J109s, which will share guns for some toe-to-toe action in their Irish Championships.

And among the cruiser-racers, the beating heart of the event, you’ll find a slew of top club racers facing off against crews returned from the Commodore’s Cup.

The newly-swelled ranks of the SB3 class are expected to number into the forties, with entries coming from as far afield as Australia.

For the slightly more sedate, yet no less competitive, forty-something entries flesh out the increasingly popular white sails gentleman’s class.

All that remains is to get thee to the Rebel County for another edition of Ireland’s premier regatta. It’s all there once again – everything that makes the week as special as it is. The line-up is solid. The stage is set. Cork it.

The Admiral's View

Describing himself as a ‘reluctant admiral’ when it comes to telling his story, Mike MacCarthy started sailing in dinghies at the Royal Cork Yacht Club at about nine or ten years of age. He’s now been involved for 30-odd years having worked up to admiral, a position he will fill for the next 18 months having started in the position in January 2008.

Enjoying his tenure, looking forward to Cork Week and commenting on what it means to be admiral, MacCarthy maintains that, “the club here is quite large and there are a number of different sections: racing, dinghies, cruising, and motor-boating, and each group has their own social element. I have to try and represent every one of these and not just the club itself, which makes the job time-consuming, yet very interesting”.

Putting a slight sail to his own story, MacCarthy acknowledges “I’m from the racing fraternity and the name of my boat is Checkmate – a family association – which is a racing cruiser, and I enjoy racing in West Cork and go to Dublin on a regular basis, and I’ve been to Dún Laoghaire Week several times”.

If the Royal Cork Yacht Club had the ear of Government, MacCarthy would like to see “a better system to allow the club develop its facilities, both land- and water-based. For instance, if I had a €5 million donation tomorrow, I wouldn’t be able to build a marina. Or a slipway. The planning regulations and the red-tape between The Department of Communications, Energy and Natural Resources, valuation departments and county councils (even though Cork County Council has been very good to us and has been very understanding) is a nightmare. We have a wish list of a number of projects we’d like to do including extending our marina, putting in a crane, and developing an extra slipway. However, with all the different departments to negotiate with, it’s incredibly difficult to improve the quality of the club.”

Party Town

Once in or around Crosshaven, when you’re not mesmerised by the delights in the marina, there are walks in every direction to clear the mind or exercise the body, including a number of designated coloured routes like the rising blue and yellow lines which, while having spectacular views of Spike Island, Haulbowline, Rushbrooke and Cobh, also offer a good vantage point to see the starting line for Royal Cork Yacht Club racing. On this walk you’ll also come across Camden Fort (or Fort Meagher), one of the region’s historical landmarks, famous for its magnificent tunnel and fortifications. Crosshaven is also famous for its two holy wells on the edge of Cruachan woods, and its limekilns, on the Carriagline Road which were once used for firing, baking, drying and hardening clay.

While there are a number of ways to get to Crosshaven, prices to Cork, from say Dublin, are around €90 (premium) return by train, or €85 by plane. If you’re driving, the route goes through Cork city following the signposts for the Ringaskiddy Ferry Port until you arrive at the Shannonpark roundabout. From there take the second exit towards Carrigaline and finally at second next roundabout take a left and follow the signs and 13 miles to Crosshaven. If you thinking of visiting you won’t be disappointed. See you there for Cork Week.