Displaying items by tag: W M Nixon

Tall Ships & Sail Training – Ireland's Atlantic Youth Trust Will Give It A Different Spin

#tallships – Rugged sailing in romantic tall ships; the camaraderie of the sea; character development. It's an inspiring combination which has gripped maritime nations for more than a century as sail has given way to more utilitarian sources of power. First there was steam. Then steam in turn was superseded by diesel and even nuclear power. And with each stage, there has been a remorseless drive towards reducing manning levels.

So what on earth is there now to occupy people who, in a former era, might have found a meaningful role in life as crew on board a sailing ship? For with each new development in shipping, we realise ever more clearly that large sailing ships were one of the most labour-intensive objects ever created.

However, we don't need to look to the sea to find areas of human activity where technological development has made human input redundant, and large sectors of the population largely purposeless. It's the general social malaise of our time. So for many years, the majority of maritime countries have found some sort of solution by an artificial return to the labour-intensive demands of sailing ships.

But in an increasingly complex world with ever more sources of distraction and entertainment, does the established model of sail training still work as well as it once did? W M Nixon meets a man who thinks we need a new vision for best using the sea and sailing ships to meet the needs of modern society's complex demands.

Tall Ships and Sail Training........They're evocative terms for most of us. Yet the buzzwords of one generation can surprisingly quickly become the uncool cliches of the next. That said, "Tall Ships" has stood the test of time. It's arguably sacred, with a special inviolable place in the maritime psyche.

So when we see a plump little motor-sailer bustling past with some scraps of cloth set to present an image of harnessing the wind's timeless power, we may be moved to an ironic quoting of Robert Bridges: "Whither, O splendid ship......" But somehow, citing Masefield's "a tall ship and a star to steer her by" would seem to be beyond the bounds of even the worst possible taste.

There's a simple purity about "Tall Ships". It works at every level. Google it, and you'll find the academics claim that it became official with its use by John Masefield in 1902 and Joseph Conrad in 1903, though Henry David Thoreau used it much earlier in 1849. But Conrad being the benchmark of most things maritime in academia, 1903 seems to be set in stone.

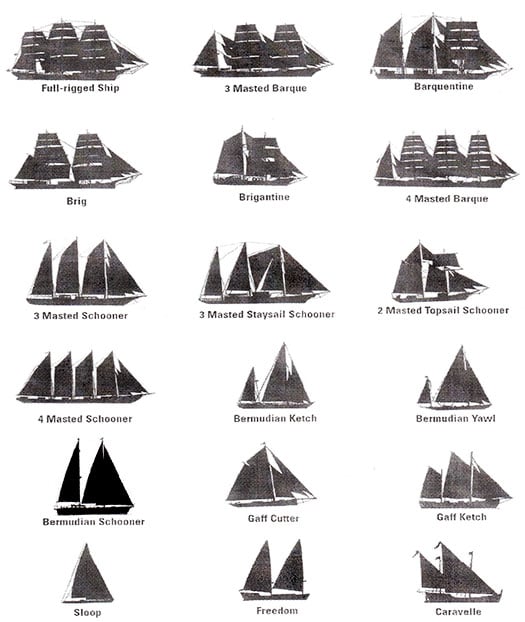

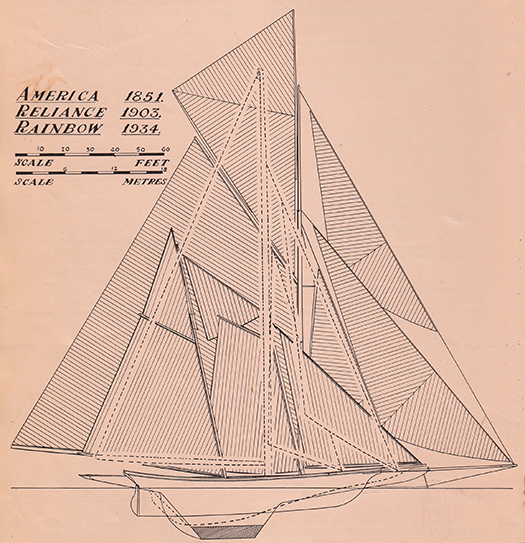

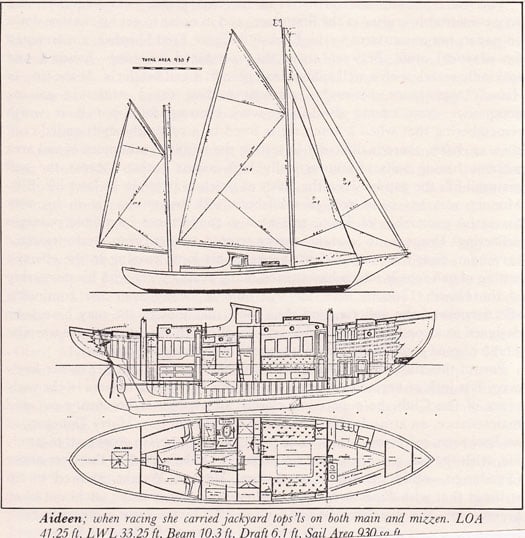

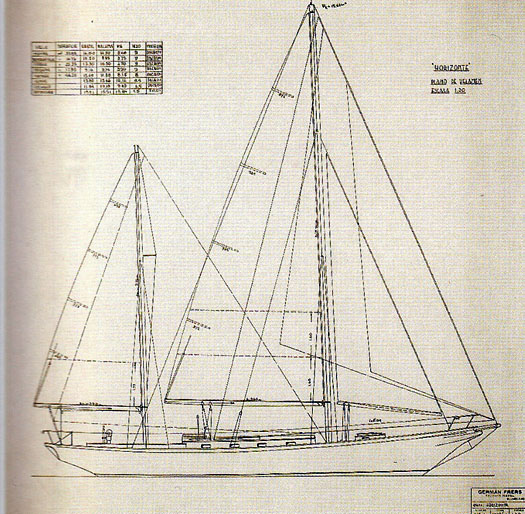

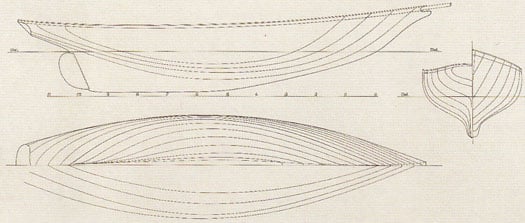

We all know what is meant by a true Tall Ship, but as these rig profiles indicate, the proliferation of sail training programmes has led to an all-inclusive approach

Yet at the vernacular level, it has been there much longer than any of them. There's a bit of maritime meteorological lore which our academics would probably dismiss as vulgar doggerel, but I've found it still moves me. When far at sea, with the underlying swell increasingly in evidence and the weather conditions which it describes clearly developing overhead, inevitably you'd remember this little couplet:

"Mackerel sky and mare's tails,

Make Tall Ships carry low sails".

It's not Yeats. But when you're on a formerly blue sea now turning grey and far from anywhere in a 25-footer, it's a little thought which can still make the hairs stand up on the back of your neck. And it's that mention of "Tall Ships" which gives it the added resonance. So things stand well with the phrase "Tall Ships". But what's the word on the continuing viability of "Sail Training"?

"I'm fed up with the constant use of the term "Sail Training". It's bandied about so much it has become meaningless. And always talking about "Sail Training" limits the scope of what we're trying to do. If we could find some useful phrase to replace "Sail Training", but something which is also more visionary than the very pedestrian "Youth Development" which is sometimes replacing it, then maybe we could go a long way to capture the imagination both of our potential supporters, and of the young people we hope will want to come aboard the ship".

The speaker is Neil O'Hagan, busy Executive Director of the Atlantic Youth Trust, which is actively developing ways and means of building a 40 metre sailing ship which will serve all Ireland in a wide variety of functions. And as he has immersed himself in this challenging project when he is clearly a very able person who could name his price in many roles in high-paying large corporations, it behoves us to pay attention.

We have been skirting the AYT and its project several times here recently. But as we gradually emerge from the recession and see what is still standing, for some reason with every passing week we find it ever more disturbing that the Irish Sail Training Brigantine 84ft Asgard II was lost nearly seven years ago by foundering, and the Northern Ireland Ocean Youth Trust's 60ft ketch Lord Rank was lost after striking a rock five years ago.

Far from being swept under the carpet, it's a double whammy which has to be faced and dealt with as 2015 rolls on with the biggest Tall Ships assembly ever seen in Ireland coming to Belfast, and not an Irish Tall Ship worthy of the name to represent us.

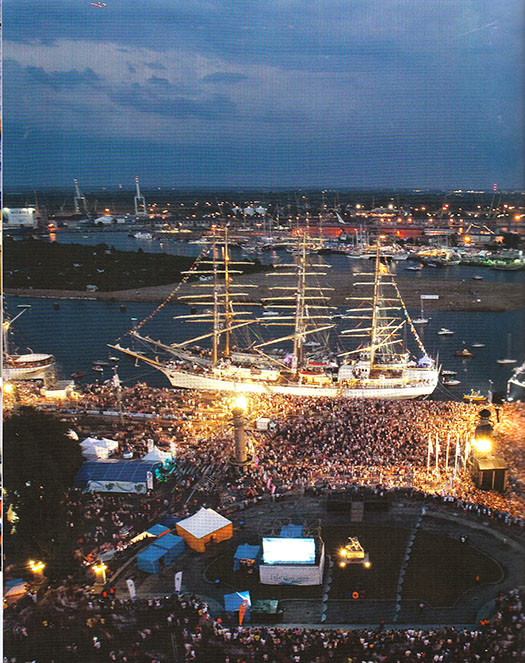

The popular image of Tall Ships is a crowded port with a fun-filled crowd...............

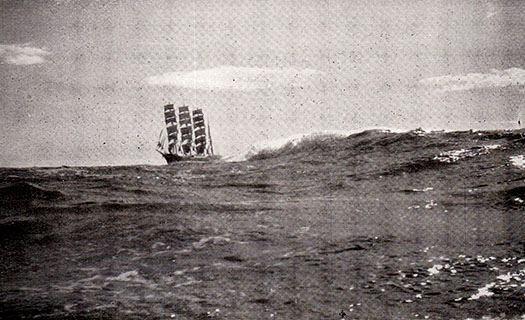

.....yet for many old salts, the true image is the lone ship at sea, going about her business. This photo of a four-masted barque was taken from a small cruising boat in the 1930s

But an ideas-laden shooting of the breeze with O'Hagan soon shows that we're going to have to learn to think a long way out of the box before we begin to meet the demanding expectations of this man and his board of trustees and directors, and the much-anticipated presence of the Tall Ships in Belfast is only a trigger to help activate a much more complex vision. Neil O'Hagan hopes not only to be instrumental in the creation of a new Irish sailing ship, but he also hopes to change the way in which we perceive such a vessel, and our expectations of the way she will be used.

In our initial blog on this back on January 17th, we thought we were making a tellingly adverse point in suggesting that the barquentine Spirit of New Zealand - which the AYT reckons will provide the best model for the development of their project – is not so much a sail training tall ship as we know it, but rather, with her large complement of 40 "trainees", she's more of a floating schoolship which happens to set sails.

Far from being blown out of the water by this "damning" criticism which I and others had voiced, O'Hagan was delighted that we'd lit upon this aspect of the plan. "Old-fashioned sail training has had its day" he says. "When education authorities and social service bodies and welfare funds and philanthropic organisations are looking for some way to provide interesting, satisfying and ultimately long-term-beneficial experiences for young people of all backgrounds and varying states of mental health including the very happily normal, they expect a much broader curriculum than is provided by the traditional sail training model".

"And come to that, so do the young people themselves. If sailing is genuinely their great leisure interest, they'll be into it already at a personal level among like-minded friends. But if they're more typical young people of today, they'll have a wide range of interests, and during the ten day cruises which we hope to make the backbone of the new ship's programme, the sailing will only be part of it."

Away from the day job - Neil O'Hagan helming a Dragon

Its not that O'Hagan is anti-sailing. Far from it – he has been seen in the thick of things in the midst of the International Dragon Class in recent years. But a good liberal education with time in the Smurfit Business School in UCD and extensive family links all along Ireland's eastern seaboard north and south, plus direct business experience in both Dublin and Belfast, give him a breadth of vision to provide the AYT with a real sense of purpose.

The Atlantic Youth Trust has been quietly building itself since it emerged from a representative workshop researching the building of a sailing ship for Ireland, held in Dublin Port in the Spring of 2011. From that, a Steering Group of Lord Glentoran and Dr Gerald O'Hare from the north, and Enda O'Coineen and David Beattie from the south – all of whom had worked together before on other north-south youth sailing projects – was set up, and they commissioned a professional consultancy group – CHL Consulting of Dun Laoghaire – to work with them in producing a Vision & Business Plan, which eventually ran to 96 detailed pages.

The Chairman Lord Glentoran (Gold Medallist at the 1965 Winter Olympics) at the AGM of the Atlantic Youth Trust with Executive Director Neil O'Hagan (left), Sean Lemass and Director Enda O'Coineen (right)

In due course, the Atlantic Youth Trust emerged with Olympic Gold Medal veteran Lord Glentoran as Chairman. And with Neil O'Hagan as Executive Director, the show was on the road with the detailed worldwide investigation of 25 successful educational schemes involving sailing ships - note we've dropped that "sail training" tag already. And in New Zealand they found something that was really new, something that fell in with their view that the double loss of the Asgard II and the Lord Rank provided an opportunity for a truly fresh look what a national sailing ship might be and do.

It's an extraordinary place, New Zealand - particularly from a maritime point of view. Far from seeing their isolation as a drawback, they use it as an advantage for fresh thinking. And they don't cling to time-hallowed ways brought over from "the old country". On the contrary, being in a new country is seen almost as an imperative for trying new ways and ideas, hence they're at the sharp end of top events like the America's Cup.

And as they were far from the fleets of established tall ships in Europe and America, with the Spirit of New Zealand they had to develop new ways of using a vessel which would spend much of her time cruising their own extensive and very varied coastline on her own, distant from the Tall Ship sailfests which are such a feature of the programme in the more compact and crowded parts of the world.

Spirit of New Zealand is barquentine-rigged

Thus by geographic necessity. New Zealand is ahead of the curve in developing ways of contemporary validity in the use of large sailing ships. We all hear of what a marvellous party the Tall Ships will activate in Belfast, just as they've done before in Dublin, Cork and Waterford. But hold hard just a moment. Isn't sail training aimed at young people mostly between the ages of 15 and 25? Surely their central involvement in vast open air quayside parties - with the inevitable underage alcohol intake possibilities – is totally at variance with the healthy idealism of the concept?

For sure, the organisers of modern Tall Ships Festivals go to enormous effort to ensure that they're genuinely family-friendly events. But the ancient traditions of sailors in port can be difficult to escape. So when you've a proposed programme which is essentially based on recruitment through continuing contact with secondary schools and similar age cohorts – as is the case with the Atlantic Youth Trust project – then it becomes increasingly desirable to have a ship which is large enough to be self-sufficient, with a viable way of onboard life built around large shared areas, such that the traditional waterfront-oriented harbour visits will no longer be such an important part of the cruise programme.

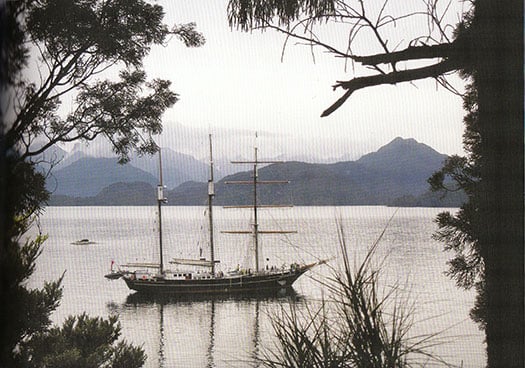

Splendid isolation. Spirit of New Zealand in an anchorage remote even by New Zealand standards

Packing them in....as she carries a crew of 40 trainees, and with space required for extensive communal areas, Spirit of New Zealand's bunks are efficiently planned

Of course the new vessel will take part in Tall Ships Races and Tall Ships Festivals, and of course she'll make the occasional ambassadorial visit, both along the Irish coast and abroad. But with the underlying philosophy of the ship being largely self-sufficient of shoreside distractions other than when they're environmentalist and educational ventures, sometimes with an expeditionary element, then the more gregarious aspects of her yearly routine will be kept well in perspective, and everyone will be the better for it.

As it's essentially a cross-border venture, equal funding from the two governments – each of which it is hoped will put up 30% of the capital expenditure - is anticipated, and with a fresh tranche of Peace Process money on the horizon, the resources are gradually building as people get used to the idea. There has also been much technical background research, and leading naval architects Dykstra of The Netherlands are on the case with an impressive scenario, for as Trustee and Director David Beattie has put it, this one isn't going to be cobbled together, it's going to be a "best in class project".

As the planned use of the vessel is essentially civilian, she will be Ireland's sailing ship without being the national sailing ship. There's more than a slight difference to the Asgard situation. In many other countries, the most impressive tall ships are part of the naval service, but in Ireland we have a Naval Service sailing vessel already, she is the ketch Creidne which was the national sail training vessel between the decommissioning of the first Asgard in 1974 and the commissioning of Asgard II in 1981. In recent years, she has had a major refit and is now actively sailed, but as Ireland's Naval Service is so essentially Cork-based, the Creidne is very much part of the scene in Cork Harbour and the Naval Base at Haulbowline.

The Naval Service have Creidne for sail training purposes for their own personnel. Photo: Bob Bateman

In fact, although the Atlantic Youth Trust does have a Cork element to it, and advisers include several leading figures in the Cork marine industry, the reality is that it is first and foremost a cross-border enterprise between offices in Dublin and Belfast.

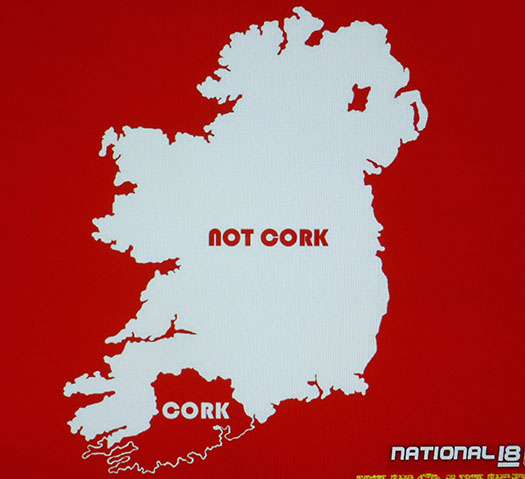

This means that Cork – which is the true capital of maritime development in Ireland, and I mean that in all seriousness – is an associate port to the Atlantic Youth Trust project, rather than a central pillar of it. But I don't think the people of Cork would wish to have it any other way. When I was in the southern capital for the fund-raiser for the new National 18 class development a month or so ago, Class President Dom Long kicked off proceedings by explaining how it was the Corkonian sense of independence which had inspired the mighty leap in National 18 design. He did this by showing a map which neatly illustrated the Cork sailor's view of Ireland.

The Cork sailor's view of Ireland

It says everything. But I don't think the Atlantic Youth Trust should lose any sleep over the fact that they might be seen as being on a Dublin-Belfast axis from which Cork is as usual going its own sweet way. 'Twas ever thus. And anyway, in the end the Corkmen will probably provide many of the officers for the proposed new vessel to which we wish, on this fine Easter Saturday morning, the very fairest of fair winds.

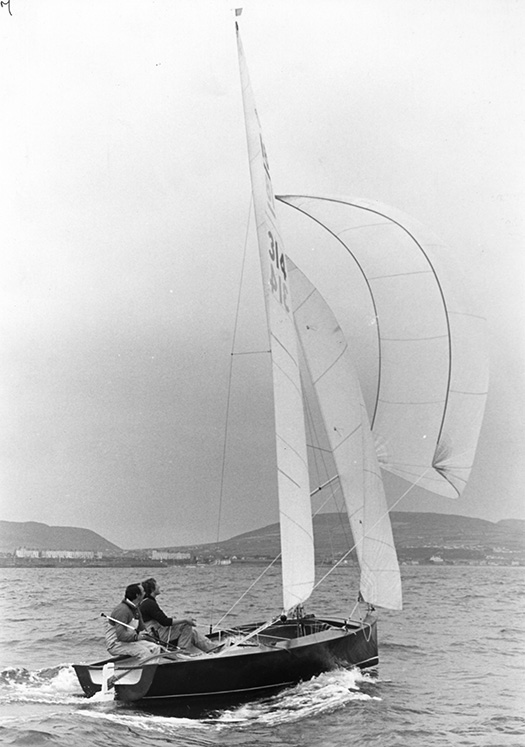

National 18s Take Dinghy Racing Class Onto A New Plane

#national18 – There are some special dinghy classes. There are some very special dinghy classes. And then there are the National 18s.

You can see any number of reasons why this unique class, celebrating its 80th birthday in just three years time, is in a league of its own. A three-man boat with one of the crew on a trapeze, its crewing set–up requires a level of sociability which is further emphasised ashore, where their après sailing is the stuff of legend.

At all the centres where it is sailed, and at places upon which the National 18s have descended for a championship, we know they've left behind a formidable reputation for determined but good humoured conviviality, combined with great sportsmanship.

Yet while it is easy to understand the class's popularity among its adherents when you see them in high spirits as a group, there's no getting away from the fact that in today's dinghy terms, 18ft is a lot of boat. The mood of the National 18s may often seem light-hearted. But keeping one of these boats in prime condition and well crewed is not something for the casually-interested.

It requires real commitment, yet that is something which National 18 sailors seem to have in spades. And now the class has taken on a new lease of life with the development of a fresh take on the National 18 parameters by legendary designer Phil Morrison. But rather than being launched as a commercial venture, the new boat is being developed from within class resources, which has involved several imaginative fund-raising ventures. W M Nixon found himself being drawn into one of them.

It's official, The Cork Harbour National 18 Class are brilliantly capable of running a booze-up in a distillery. And just to make it even more challenging for their supportive members and many friends, they ran this particular fund-raiser for the new Phil Morrison boat in the Jameson Distillery in Midleton in East Cork on the first Saturday night of Lent.

Of course, like all Ireland on St Patrick's Day three weeks later, they got a special dispensation for the partying to continue unhindered by thoughts of Lenten piety. There was plenty of time for that next morning. But meanwhile, right there in the heritage and high tech splendour of the Midleton facility where tradition and new science are dynamically allied, the National 18 crews went at it good-oh, and the class's Development Fund was greatly enhanced.

In fact, I'm told the financial targets were comfortably exceeded, but as Class President Dom Long and the ever-energetic Tom Dwyer didn't tell us the targets in the first place, we'll happily take their word for it. All I know is that it was one helluva night, and only the National 18s could have done it.

Let's party! Colman Garvey's vintage National 18 welcomes guests to the Midleton Distillery for yet another event in a series of fund-raisers which have supported the development of the new boat from within class resources. Photo: W M Nixon

It's a class which – thanks to being a restricted design rather than a hidebound one-design – is able to wallow happily in its history as it thrusts towards new designs which keep up the spirits of its established sharpest sailors, while also encourage the vital new blood.

So how did it all come about? Well, thanks to a prodigious book written by Brian Wolfe of the boat's history, published in 2013 to mark the class's 75th Anniversary, we get some idea of the inevitable complexity of the story. The class started in 1938 in the Thames Estuary where there'd been several local one design or restricted "large dinghy" classes around the 18ft mark and soon – under a National Class imprimatur from the Yacht Racing Association – it spread to several other centres.

Needless to say, World War II from 1939 to 1945 brought any further growth and most sailing activity to a halt, but by 1947 things were looking up again, and in the straitened post war circumstances, the National 18 found its niche. Back in 1938, Yachting World magazine had sponsored a design to the class's rules by Uffa Fox, and that became the clinker-built Uffa Ace, which continued to be the backbone of the class for many years after the war.

It was Whitstable in the far east of Kent which produced most of the initial impetus for the class, and local builders Anderson, Rigden & Perkins made a speciality of it. In fact, ARP-built Uffa Aces were soon virtually the definitive National 18. Yet ironically we cannot confirm at the moment if the oldest National 18 still sailing – Richard Stirrup's 1938-vintage Tinkerbelle which races with the classics divison at Bosham SC on Chichester Harbour – is an ARP boat.

It's ironic because Tinkerbelle's first home port was Howth. It wasn't until I was writing the history of Howth YC for its Centenary twenty years ago that awareness surfaced that there'd been the nucleus of a National 18 class in Howth in 1938.

There were just three boats – John Masser's Wendy number 14, Tinkerbelle number 15, and Fergus O'Kelly & Pat Byrne's Setanta, number 16.

Tinkerbelle (15) being sailed by Aideen Stokes in 1939, with John Masser's Nat 18 Wendy (later Colleen II) astern, and the Corbett family's Essex OD Cinders abeam.

Tinkerbelle as she is today, the oldest National 18 still sailing. Her home port is Bosham on Chichester Harbour. Photo courtesy Richard Stirrup

Tinkerbelle seems to have been owned by a syndicate in which the Stokes family was much involved, though in the class history her earliest owner is listed as Bobby Mooney, son of the renowned Billy Mooney of Aideen fame. However, around Howth, Tinkerbelle was best remembered for being raced with considerable panache by a non-owner, Norman Wilkinson.

But when Norman returned from war service in 1946 determined to sail just as much as humanly possible, he found that the National 18s had faded away, and the only way he could get regular racing was by buying the 1898-built Howth 17 Leila, which he duly raced with frequent success right up to the end of his long life in 1998, by which time Leila was a hundred.

It's intriguing to think that, with one or two twists of fate in Howth, Norman Wilkinson might have been renowned as a star of the National 18s taking on the likes of class legends such as Somers Payne and Charlie Dwyer of Cork, where the class – having started with just two ARP boats in1939 - held fire for a while, but got going big time in the late 1940s and early '50s with several builders all round Cork Harbour creating them in local workshops.

That was one of the attractions of the National 18s. They were big enough to appeal to people who didn't fancy skittish little dinghies, yet they were small enough to be constructed by artisan boatbuilders who could produce lovely boats. But the owners – having laid out what were considerable sums of money at a time when Ireland seemed to be in a state of permanent economic depression – were disinclined to go the final stage of having the boats properly measured and registered with the class. This caused increasing problems, ultimately solved by a high level of diplomacy as the National 18s' popularity grew, and the opportunities arose for the Cork boats to go across the water to race in big-fleet competitions.

At one stage, class numbers were so healthy at many centres that in Britain they had Northern and Southern Championships, reflecting the primitive state of road movement of boats. Dinghy road trailers – particularly for hefty big 18-footers – were still in their infancy, so all sorts of ingenious methods were used to get boats to distant events, with a Whitstable boat on at least one occasion getting to Cork as deck cargo aboard a Coast Lines vessel on its regular route which took in Rochester in Kent and eventually Cork among several ports.

The National 18s in their classic prime, with immaculately vanished clinker-built hulls, and setting lovingly-cared-for cotton sails. Here, Crosshaven's greatest National 18 sailor Somers Payne (Melody, 206) is being pursued by Alan Wolfe in Stardust 63), while up ahead Charlie Dwyer with Mystic (208) is doing a horizon job, with the legendary Leo Flanagan of Skerries lying second at the helm of Fingal. The photo was taken during a Dinghy Week at Baltimore, and it is memories like this which inspired Brian Wolfe (son of Stardust's owner-skipper) to undertake the mammoth task of collating and writing the class's history.

In Ireland, centres which saw interest in the National 18s included Dunmore East, Clontarf and Portrush, but as Dun Laoghaire was committed to the 17ft Mermaid, the only place on the East Coast with really significant National 18s numbers was Skerries, where the incredible Leo Flanagan set the pace driving his Jensen Interceptor ashore, and racing his no-expenses-spared ARP-built National 18 Fingal afloat in somewhat erratic style.

Leo was a ferocious party animal, and when the Skerries and Crosshaven National 18s united in going to the big class championship at Barry in South Wales in the mid 1950s, Leo was very disappointed to discover that, just as the party was really getting going, the club barman had every intention of closing at closing time. The very idea....Leo solved the problem by buying the entire bar for cash on the spot.

As far as Leo was concerned, sailing was for parties, so when he heard of the highly-organised Irish Olympic campaign towards the 1960 Olympics in Rome, he got himself to Rome, as Olympic sailing promised Olympian parties. To his distress, he was ordered out of the Olympic Village by the Irish squad, who wanted no distractions. But to their distress, the bould Leo then turned up next morning for the first day's racing, officially accredited and highly visible in his new role – he had become manager of the Singapore team.

It seems that in a harbourside bar the night before, he'd met the helmsman of the Singapore Olympic Dragon (as it happened, the only Dragon in Singapore), who was racing in the Olympics as a personal venture. As the biggest rubber concessionaire in Malaya, he could well afford to do so. But this meant he was also Team Manager, and when Leo met him, the Singapore skipper was much upset, because with his sailing duties and need to get a good night's sleep before each day's racing, he was simply unable to take up all the official invitations which any Olympic Team Manager received.

He felt he was badly offending his hosts, and completely failing the Singapore sailing community So Leo, out of sheer kindness, agreed to be the Singapore Olympic Sailing Team Manager, giving selflessly of his time, energy and great wit in the front line at all the best and most fashionable parties throughout the 1960 Olympic Regatta.

All of which has little enough direct connection with the story of the National 18s, but it gives you some idea of the style of the people who have been involved in a long tale which will soon have been going on for eighty years. Yet beyond the parties and the many scrapes they got into, there was also much serious sailing and boat development going on, for although the Uffa Ace was the most numerous design in the growing fleet, anyone could have a go provided they fitted within the class rules.

But by the mid-1960s, it was clear that the traditional concept of a clinker-built National 18 was losing its appeal, and in 1968 the Class Association asked Ian Proctor to design a National 18 to be built as a smooth-hulled fibreglass series-produced boat, with bare hulls to be available for owners who wished to finish the boats themselves.

However, being mindful of keeping existing wooden boats competitive, the new boats were built much heavier than their glassfibre construction really required. Yet they looked good, and the first one Genevieve (266) was delivered to class stalwart Murray Vines, who sailed with the Tamesis Club on the Thames. There, the river may have been pretty, but it was so narrow that when the Tamesis people secured a major championship, they took their entire race management team down to the coast to attractive sea venues where the National 18s could do their thing with style and space.

That said, it was far from style and space they were reared. Murray Vines' son Jeremy – who is proud owner of the very first production version of the Phil Morrison Odyssey design which the class has been developing for the past two years – recalls his own earliest experience of championship competition with the National 18s in 1949 aged 11. He and his brother crewed for their father in 18/51 in a championship on the Medway in Kent, and they lived afloat on the boat, for in those days many National 18s lay to moorings.

Perhaps as a reward, the father built the two young Vines brothers their own International Cadet Dinghy the following winter. But Jeremy has remained loyal to the National 18 class to the point of being the pioneering owner for the new version of the design despite being at a certain age which you can work out yourself from that data given for the Medway in 1949. That said, he has given himself more space for his sailing as he has moved his base from Tamesis to Lymington, and in addition to the National 18, he cruises and races the Dufour 34 Pickle, a sister-ship of Neil Hegarty's award-winning Shelduck which featured in this column a week ago.

That the new wave of glassfibre 18s was not going to outclass the existing boats was forcefully demonstrated in 1970, when the class held its first combined all-British & Irish Championship in Cowes, after twenty years of separate Northern and Southern events. Despite the new glassfibre boats, the classics from Cork Harbour – where they'd been in the midst of celebrating the Quarter Millennium of the Royal Cork YC - were dominant, with Somers Payne right on top of his form sailing Melody (206) to win going away, notching only 1.5 points to second-placed clubmate Dougie Deane on 14.

Cork Harbour boats took the first six places in a crack fleet of thirty-one of all the best from every top National 18 centre, and the spirit of it all was best captured by the Thames Challenge Cup for a family crew going to Royal Cork's Dwyer family – Charlie and his sons Michael and a very young Tom – who placed sixth in Mystic.

The furthest flung fleet is at Findhorn in northeast Scotland, but the huge distance involved doesn't stop Royal Findhorn YC boats competing with the rest of the class. This is top RFYC helm Stuart Urquhart's Howlin Gael racing in the Solent, and every so often the class – including those from Cork – make the long trek to Finhorn for an annual championship.

However, in terms of championship success the movement towards overall victory by glassfibre boats had begun, and 1977 saw the last championship win by a wooden boat, with Mike Kneale's Maid Mary (183) from the Port St Mary fleet in the Isle of Man. This was a hotbed of National18 racing for a couple of decades, and after Mike had completely renovated the 23-year-old formerly only so-so Maid Mary, he clinched the 1977 title at Findhorn in northeast Scotland "just before you get to Norway", as I was told in Midleton last month. There, the Royal Findhorn YC is a byword for warm hospitality ashore and hot sport afloat, but despite a strong challenge by a formidable Cork contingent, the Manxmen won out.

But having done his duty by the classic wooden boats, for 1979 Mike Kneale and his team took a different tack – they commissioned a new National 18 design from ace ideas man Jonathan Hudson, which they composite-built around Airex foam whose use other Manx DIY boat builders such as Nick Keig had been deploying for long-distance multi-hulls.

The Airex boat....Mike Kneale's innovative Woodstock on trials off Port St Mary in the Isle of Man in 1979.

Woodstock from the Isle of Man sails back into Crosshaven in 1979 with all the look of a boat which has just won the championship.

Despite – or maybe because of – her composite materials, the new boat was called Woodstock. And as Brian Wolfe's history of the class recalls, when she appeared for the well-supported 1979 championship in Crosshaven, "there was much debate", not un-related to the fact that Mike and his crew of Rick Tomlinson and Ross Thomas swept the board, taking the championship for Mike's fourth time in a clean sweep with the top boat from the home Cork Harbour fleet being Albert Muckley's Eastern Promise (323) in second overall for East Ferry SC.

So where was Somers Payne? Well, after dominating the national championship leaderboards since 1958 with the wooden Melody, in 1979 Somers was making his first foray into campaigning a glassfibre boat, and while he may have been third, the writing was on the wall, and the class was moving to class.

And there was new life at Royal Cork. The Royal Cork YC's National 18s were having one of their periodic re-births, and while Woodstock may have won the title, her designer reckoned it was only by extra skill that they stayed ahead of a new wave of young talents whose helming skills had been honed in events like the Admiral's Cup and many national and international championships in all sorts of boats. Their zest for international competition was buoyed up by the knowledge that, back home in Crosser, they had ready-to-go racing in the National 18s which was not only great sport, but somehow much more fun than sailing in other boats.

This continued level of enthusiasm at all ages meant that when the National 18 pace showed any signs of slackening, the Cork Harbour division could be relied on to get things up and moving again. Thus when the changeover to glassfibre had become complete at the front of the fleet, with many other owners happy to race their vintage boats in a classics division, some of the Corkmen questioned why new glasfibre boats were still being built overweight in order not to out-perform boats which now saw themselves as a different part of the class in any case.

The National 18 fleet in Cork Harbour was mustering serious numbers with the lighter GRP boats from O'Sullivan's of Tralee. Photo: Bob Bateman

So the Crosshaven people got the moulds from England, and encouraged the moving of them to O'Sullivan's Marine in Tralee (incidentlally just about as far west on land as you can get from Whitstable in Kent), where they were used to build a whole new wave of lighter boats which became the National 18 class as most of us have known it until this year. Now, the new moves into the Phil Morrison boat are providing a fresh direction for a class which nevertheless takes careful steps to ensure that older boats have their place in the sun with a chance of realistic racing against similar craft.

Although Jeremy Vines of Tamesis and Lymington is the owner of the first of the new boats (she's number 401, and is called Hurricane in honour of the very first National 18 built by Anderson, Rigden and perkins in Whitstable in 1938), he is untinting in his praise for the energy and vision of the Cork harbour division of the class in having the idea and then promoting the new Phil Morrison boat, and he makes a particular point of applauding the very tangible support which has been given to the project by the Royal Cork Yacht Club.

Into the blue.....Hurricane (number 406) is unveiled a fortnight ago at the Dinghy Show.

It's almost unfair, in such a community-based grass roots project, to single out anyone for special praise, but I got the feeling that folk like Colin Chapman, Dom Long and Tom Dwyer have been right there in the thick of it from the beginning.

The prototype having been tested and approved every which way, the moulds were made and the first dark blue hull emerged early in the New Year in one of the workshops which Rob White runs at White Formula Boats at Brightlingsea in Essex. So having been built at Tralee on the shores of the Atlantic for more than a decade, National 18 production is now back on the shores of the North Sea, but the spirit of the class at every location, regardless of where it might be, seems keener than ever.

The first of the new boats - of which sixteen have now been ordered – was Jeremy Vines' Hurricane, number 406, which was unveiled at the recent Dinghy Show in London. For a new generation which has been raised on the Phil Morrison-designed RS 200, this latest variant on the continuing National 18 story will speak volumes, and with eloquence. But it says everything about the spirit of this exceptional class that she rings a bell with seasoned National 18 sailors too.

The gang's all here. The new boat celebrated at the Dinghy Show with a group including many of those actively involved in its development, notably Colin Chapman, Tom Dwyer, Dom Long and Jeremy Vines.

The movers and shakers are (left to right) Tom Dwyer of the Cork Harbour National 18s, designer Phil Morrison, Cork Harbour Class President Dom Long, Jeremy Vines (owner of the first boat to the new Morrison design), and Rob White of White Formula Boats

Did The America's Cup Destroy Belfast Lough Sailing?

#americascup – The 35th America's Cup series will be staged in Bermuda in 2017, and already the first team – Ben Ainslie Racing – is starting to settle into its base in the islands at the beginning of a developing process which, it is hoped by locals, will contribute significantly and sustainably to an economy which is by no means as prosperous as the popular image of Bermuda would suggest.

Yet past experience of being involved with the America's Cup circus suggests that while there are definitely immediate and highly visible benefits, they're ephemeral and are more than offset by a hidden but very definite downside. And the pace of the event at its peak is at such a level that almost immediately afterwards there's a sense of anti-climax and recrimination which can poison a sailing centre's atmosphere for years. W M Nixon considers how sailing's most stellar event affected Irish sailing, looks at a more recent continuation of this story, and then takes up the tale of an old boat whose class's health suffered collateral damage from America's Cup fallout.

It was while tracing the story of Tern, a 37ft William Fife-designed Belfast Lough One Design built by John Hilditch of Carrickfergus in 1897, that we stumbled into what is arguably an example of the America's Cup having a seriously damaging effect on local sailing.

Somehow or other, Tern has survived, and is currently being restored to international standards in Palma, Mallorca. But it was when a couple involved with her restoration came to Ireland shortly after Christmas to spend some time researching her history that we had to face the fact that while Belfast Lough's involvement with the America's Cup is seen as a glamorous and still-celebrated era, as far as everyday sailing is concerned it did little but harm.

The context is intriguing. Belfast in 1897 was the Mumbai of its day. From a population of around 80,000 in 1850, by 1910 its unprecedented expansion through massive industrial innovation and development, built largely around ship-building and linen manufacturing, had seen numbers soar towards 300,000. The city was a byword for pollution, over-crowding, and ill health, but equally it was noted as a place where anyone with energy and an innovative manufacturing idea was expected to have made their fortune within ten years, and around three or four years to start reaching towards wealth was seen as a not unreasonable aim.

In such a frenetic and ambitious atmosphere, sailing on Belfast Lough developed apace, and it developed ambitiously and competitively for all that the lough, while providing splendid sailing water, lacked any really good natural anchorages. New boats and new boat types appeared with bewildering rapidity, and a sort of one design keelboat concept was being accepted by the early 1890s in order to make good racing accessible to keen young men at a reasonable price. There may have been much underlying wealth about, but spending it on extravagances like large and expensive yachts was frowned upon.

By 1896 a young whiskey distiller called James Craig (he later became Lord Craigavon) was promoting the idea of a strict One Design keelboat around 23ft LOA, and about 16ft LWL, designed by the great William Fife in Scotland, but built on the lough by John Hilditch at his Carrickfergus boatyard. As the pioneer of the concept in the locality, Craig called the new class the Belfast Lough No. 1 OD, but the first boat to the design, his own Fugitive, was barely finished before the One Design keelboat ideal was taken up with enthusiasm by another group which decided they wanted something to the same concept, but much larger.

These new boats, the first of which were rapidly built in time for the 1897 season, were almost exactly enlarged versions of Fugitive, but were all of 37ft overall and 25ft waterline. In a case of Might is Right, the bigger boats now became the Belfast Lough Number Ones, while Fugitive and her sisters were demoted to Number 2, and by the early 1900s they'd slipped still further to become the Number 3s when yet another class appeared, this time around 31ft LOA.

There were enough of the new 37ft Number Ones afloat to make a real impact on Clyde Fortnight in 1898, and as they were well able to sail across Channel to do so, they were arguably the world's first offshore one design. The previous year, some had visited Dublin Bay, where they so impressed the locals that they were the inspiration for the Dublin Bay 25s, to the same lines but built to a higher specification and with lead ballast keels, rather than the Belfast Lough boats' cast iron keels.

Whimbrel on the Clyde in 1898. They'd the potential to be the world's first offshore one design, but offshore racing hadn't yet been invented. Whimbrel is currently undergoing restoration in Bordeaux. Photo courtesy Gordon Finlay/RUYC

By the middle of the 1898 season, the Belfast Lough One Designs were in all their glory, and our header photo from that season shows a class which surely promised at least a decade of great racing. Yet their peak years barely stretched beyond the turn of the century, and within five years they scarcely existed as a class. Well before the Great War broke out in 1914, they were starting to spread near and far in a scattering which was to continue post war and in most cases ended up in their eventual demise. But remarkably, two have survived and both are undergoing restoration, Whimbrel Number 8 in Bordeaux and Tern, number 7, in Mallorca.

Patricia O'Connell and Alan Renwick live in Palma where he is a master craftsman with Ocean Refits while she – a former Honorary Secretary of a Georgian preservation society in Dublin – has undertaken the tracing of Tern's story, as Tern's restoration is Alan's current project. They arrived in Dublin in the dying days of 2014, and by the time they headed back to Palma well into January, they'd spent time in Cork and Northern Ireland following the old boat's elusive trail, and had also called in Howth to see Ian Malcolm's Howth 17 Aura, which was built in Hilditch's yard within a year of the construction of Tern.

Still going strong. The 1898 Hilditch-built Howth 17 Aura off Carrickfergus Castle for her Centenary, April 1998. With her sister-ships, she then sailed the 90 miles home to Howth. Like Tern, she is number 7 – and like Tern, there's an element of confusion with sail number 2. Photo: David Jones

The original five Carrickfergus-built Howth 17s still sail together as part of a thriving class of twenty Howth 17s. But the impressive class of eight Belfast Lough One Designs from the same era have been remembered for more than a hundred years only as photos on the walls of the Royal Ulster Yacht Club. What went wrong?

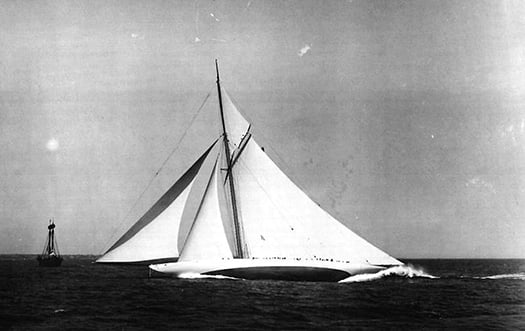

The America's Cup – that's what went wrong. In the early years of sailing's premier trophy, there was remarkable Irish involvement. After the schooner America won it with a race round the Isle of Wight in 1851, it took a while to establish a format for races to try and wrest it back from the New York Yacht Club in contests in America. During the 1870s, there were three challenges – two from Britain and one from Canada. Then in the 1880s there were three from Britain and one from Canada, the final one from Britain in 1886 being through the Royal Northern YC of Scotland, but that was because the owner's wife was Scottish – the husband was Lt William Henn whose family home was on the north shore of the Shannon Estuary.

But while the Henn family's hefty cutter Galatea was another unsuccessful challenger, at least she was seen in the waters of the Shannon Estuary. Yet although the first two challenges in the 1890s were by racing machines owned by a yachtsman whose ancestral pile was also on Shannonside, neither boat was seen anywhere near Adare Manor, the home of Lord Dunraven on the south side of the Shannon Estuary, whose two campaigns in 1893 and 1895 were unsuccessful and increasingly acrimonious.

With the passage of time, it becomes increasingly clear that Dunraven got a decidedly raw deal. But in the feverish atmosphere of rapid economic expansion in the 1890s, the world was more interested in pushing ahead with new projects rather than putting right old wrongs. Someone who saw the developing publicity and business potential in the America's Cup was Thomas Lipton, the Scottish-born grocery magnate whose American empire was thriving with a combination of his sheer love of hard work, and gift for publicity.

Lipton had noted the extraordinary level of public interest in Lt & Mrs Henn's "family" challenge in 1886 – they'd actually lived on board the Galatea at he time. But much more importantly, he'd noted the international crisis which arose from the Dunraven affair, and cannily realized that anyone who could smooth the waters with a good-tempered America's Cup challenge would attract acres of favourable coverage, regardless of the actual result.

That said, as a highly competitive individual, there's no doubting he was keen to win. But even though all five of his yachts called Shamrock making his America's Cup challenges between 1899 and 1930 were unsuccessful, with some being much more closely fought than others, he remained resolutely good humoured throughout, and expansion of his retail empire continued unabated. But what's less widely known is that while the America's Cup Shamrocks were numbered I to V, there was a sixth Shamrock, an un-numbered 23 Metre, which raced as his private yacht. It's said that when she didn't perform as well as she should have, the old man could be very grumpy indeed.

But that's all in the future. Here we are in the latter half of the 1890s, and on Belfast Lough this wonderful new class of 37-footers is spreading its wings, thriving on the fact that although the owners lived all round the lough and were members of one yacht club, the Royal Ulster YC founded 1866 and given the "Royal" in 1869, they could feel at home wherever their boats happened to be, as the RUYC had no clubhouse. This was a true sailing club, fixed only to good sailing water, and with the Belfast Lough Number Ones they could sail it well.

It was too good to last. Thomas Lipton was a man in a hurry. He knew that he needed a yacht club of international standing through which to make his first America's Cup challenge. But as he was of humble birth and very much in trade instead of benefitting from inherited wealth, there were few yacht clubs open to him. However, his parents had come from Monaghan, not only in Ireland but particularly in Ulster. In the can-do atmosphere of Belfast in the 1890s, it was indicated that the Royal Ulster might be receptive to his interest. He was soon a member, and plans were roaring ahead for an 1899 Challenge with Shamrock I.

But the RUYC had taken a cuckoo into its nest, or rather its virtual nest. It emerged that a virtual nest was not enough for the aspirations of a serious America's Cup challenger, he needed a real nest. Lipton was soon insisting that his America's Cup challenge, now irreversibly under way, would required the RUYC to have a proper clubhouse impressively sited above the waters of Belfast Lough where it was assumed he would very soon be the defender in the America's Cup.

The new RUYC clubhouse was completed at the behest of Thomas Lipton in 1899 after just 18 months work.

And he got his way. An impressive arts and crafts tower-topped clubhouse design was drawn up by James Craig's brother, the architect Vincent Craig, and the new RUYC clubhouse was opened in April 1899, having been built in 18 months flat. Well – not quite flat. They were in such a hurry for completion that there wasn't the time to entirely level the hillside site on the Bangor waterfront where the new clubhouse was built, and even today the ground floor is on two or three different levels.

That said, it's an impressive building to have been put up in such a short time, and somehow they achieved a sort of instant antiquity with it – today it seems much older than its 116 years, and it has always been thus.

But antique or otherwise, it doesn't seem to have been desired by all the members. There were 150 of them, yet only 30 contributed directly to the cost of the new clubhouse. And others took their sailing elsewhere. We live in hope of finding letters or a sailing diary from this period which will tell us what was really going on, for official club committee papers only cover what was on the agenda and recorded in the minutes. Thus even if there was an almighty row going on about the very fact of the somewhat cavalier building of this new clubhouse, at the time it would have been something known to everyone, and talked about by everyone, yet not written down simply because everyone knew of it, and it didn't happen to be directly pertinent to the business of the day. And anyway, once the clubhouse was in being, that was that – the best thing was to get on with living with it.

Yet the fact is that a distinct division arose in sailing along the south coast of Belfast Lough. The conspicuous Royal Ulster YC in Bangor became the public face of yachting in the area. But further up the lough at Cultra beside a roadstead anchorage, what had been a modest canoe club developed in 1899 into an amalgamation of the Ulster Sailing Club with the Cultra Yacht Club to become the North of Ireland Yacht Club, and by 1902 – by which time Lipton had already unsuccessfully challenged twice for the America's Cup through RUYC – the new place at Cultra had become the RNIYC, with a modest clubhouse aimed exclusively at serving its members' sailing needs rather than following grandiose ideas of international yachting campaigns for plutocrats who were only very seldom about the place, if at all.

Inevitably some of the best sailing men in the north were involved with this move to Cultra where many had always anchored their boats in any case, and others had followed. Whether or not the active membership of the RUYC was seriously depleted we can only guess. But the fact is that the relatively small membership of a provincial yacht club had somehow to find, within its membership, the essential people with the necessary talent and experience to provide the back up committee and officer services for Lipton's America's Cup Challenges, with the next one coming along as soon as 1903.

America's Cup design development 1851 to 1930. The Challenge Committee of the RUYC may have come on the scene 48 years after the era of the schooner America, but they still had to cope with the challenges posed by the design development from boats like Reliance in 1903 to the J Class Rainbow in the 1930s.

The drain on RUYC personnel resources was heavy in an era when time-consuming Transatlantic voyages by ship were required for the challenger's committee to meet with the committee of the defending New York Yacht Club. Something just had to give, and it seems to have been the level of personal sailing within RUYC, and particularly with the Number One Class.

The new RNIYC setup at Cultra was establishing its own modest new 22ft OD class, the Linton Hope-designed Fairy Class (also built by Hilditch), so they may well have seen the much larger Number Ones as simply too large, and tainted by the new vulgarity of the RUYC. Whatever the reason, the Belfast Lough Number One Class was a brilliant flame which burned only briefly as a class, even though the boats survived individually with most of them becoming fast cruisers.

But as for the America's Cup, it continued on its melodramatic way, with skulduggery par for the course. After 1903's unsuccessful challenge, when Shamrock III found herself ill-matched against the hyper-giant Reliance, the RUYC committee may have returned home to recuperate and gather strength for Lipton's next campaign. But he was scheming other ideas, and it has been only relatively recently discovered that, unbeknownst to RUYC, he was in preliminary negotiations with the Royal Irish YC on Dublin Bay to organise his fourth challenge.

Lipton and the RUYC thought they'd an impressive boat with the Fife-designed Shamrock III in 1903, but this is what they came up against in America – mega-boat Reliance

From a purely commercial point of view, you can understand his thinking. The formerly despised Irish community in the US was expanding rapidly in numbers and prosperity by 1904. Coming in with a challenge through the Royal Irish Yacht Club would hit more market targets than the narrower appeal of a Royal Ulster challenge. It was crude but shrewd business thinking. But fortunately for goodwill in the sailing community, nothing came of it. Challenge 4 through RUYC was slated for 1914, but with the Great War breaking out it was held off - with the radical and very promising Shamrock IV designed by Charles E Nicholson stored in the US – until 1920, with Shamrock IV defeated by the narrowest margin. And then in 1930 came the last challenge, the first with the J Class, but again there was defeat, this time for Shamrock V.

And thus 1930 saw the end of the Royal Ulster YC's tumultuous three decades affair with the Holy Grail of sailing. Since then, other clubs have had their collective finger burnt by the America's Cup. But it usually promises more than it gives. Most recently, sailing has been bluntly reminded of its limited appeal as a spectator sport, even when packaged as America's Cup Plus. The 34th series in San Francisco may have provided some of the most exciting racing ever seen in the event's 164 year history. It made great television for aficionados. And it may have attracted 150,000 shoreside spectators over the length of the series. But let's get it into perspective. San Francisco's Number One tourist attraction is Alcatraz. This island with its former prison fortress linked to the likes of Al Capone and other adornments of American society attracts around a million visitors a year. No matter which way you slice the numbers, that's quite a few more than the America's Cup, it doesn't cost nearly as much, and it's much less trouble to run.

Which goes some way to explain why those of us who live for this crazy old vehicle sport of ours retreat into the happy dreamworld of old boats and their winding journeys through life, often to a wonderful re-birth. And the story of Tern is a classic of its kind. From Belfast Lough she headed some time or other to Cork, we don't quite know when, but we do know she was converted to a yawl for greater ease of handling in 1914. And she was certainly in Cork in the 1920s and 1930s owned seemingly by a loose syndicate, as different owners appear at different times depending on what event she is being entered for, and in 1929 she was one of five yachts taking part in the Irish Cruising Club's Founding Cruise-in-Company to Glengarriff, owned by Capt P F Kelly.

Happy days. Aboard Tern in cruising style, complete with enormous dinghy on the starboard deck, on her way to the founding of the ICC in Glengarriff in 1929 with Captain Kelly and Dr Dan Donovan enjoying the sail

Tern in Falmouth, July 1990. Rot had long since set in within her long and elegant Fife counter, so it had simply been chopped off. Photo: W M Nixon

Tern being overcome by the heat in Andraitx in Mallorca, October 2012. Photo: Patricia Nixon

Yet by 1947 according to Lloyds Register she was in Dun Laoghaire, owned by two members of the National Yacht Club, C E Hogg and M Healy. And then she turns up in Falmouth Harbour in the 1970s and stays there for some time, but she was restored to being a cutter, not with full rig but her mizzen had to be done away with, as there was rot in her long elegant Fife counter, so it was simply chopped off to become like a Laurent Giles stern.

It was then in a little yard in a hidden creek off Falmouth Harbour that she had her first major restoration, and with that she went to the Mediterranean. But by the Autumn of 2012 she was seen in Andraitx looking a bit sorry for herself, and very much for sale. And there she was bought and taken into the specialist yard in Palma, and at the end of December 2014 Patricia O'Connell and Alan Renwick turned up in Ireland and began a pilgrimage.

Alan Renwick and Ian Malcolm aboard the latter's Aura in Howth, December 30th 2014. Aura had Tern have just one year age difference, but the same builder. Photo: W M Nixon

This took them to Howth to see the Hilditch-built Aura (like Tern, she's number 7, and like Tern, at one time her mainsail was mixed up with a number 2). Then it was down to Crosshaven to meet Royal Cork archivist Dermot Burns, who was a fund of information and original material abut Tern's twenty-plus years on Cork Harbour. Then on north to Belfast Lough for a large gathering in the Royal Ulster, a party built around the Charley family, one of whose ancestors owned Tern in 1910, and also brought in folk like noted northern sailing historian Michael Clarke of Lough Erne, and Fife yachts historian Ian McAllister who now lives in Carrickfergus. So you can well imagine that information and ideas overload was a constant risk. But Patricia and Alan survived, they got back to Palma in one piece, the work on Tern resumed, and the Tale of Tern goes on.

There's a Fife hull in there somewhere. Tern in the restoration shed in Palma

Ireland Hit The High Spot In The Sydney Hobart Race 23 Years Ago

#rshyr – Ireland's fascination with the Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race moved onto a new plane in 1991, when a three-boat Irish team team of all the talents had a runaway win in the Southern Cross Series which culminated with the 628-mile race to Hobart. The three skipper/helmsmen who led the squad to this famous victory twenty-three years ago were Harold Cudmore, Joe English and Gordon Maguire, all on top of their game.

These days, the incomparable Harold Cudmore is still a sailing legend, though mostly renowned now for his exceptional ability to get maximum performance out of large classics such as the 19 Metre Mariquita, sailing mainly in European waters.

But sadly, Joe English passed away just eight weeks ago in November in Cork, much mourned by many friends worldwide. Yet for Gordon Maguire, the experience of sailing at the top level in Australia was life-changing. He took to Australia in a big way, and Australia took to him as he built a professional sailing career. And he's still at it in the offshore racing game as keenly as ever, with 19 Sydney-Hobarts now logged, including two overall wins.

He raced the challenging course of this 70th 2014 edition as sailing master of the Carkeek 60 Ichi Ban, a boat which is still only 15 months old, having made a promising though not stellar debut in 2013's race. Also making a determined challenge was the First 40 Breakthrough with a strong Irish element in the crew led by Barry Hurley, fresh from the class win and second overall in October's Rolex Midde Sea Race.

And high profile Irish interest was also to be found aboard the Botin 65 Caro, the record breaker in the 2013 ARC Transatlantic Race. She's a very advanced German-built "racer/cruiser" aboard which Ian Moore - originally of Carrickfergus but longtime Solent-side resident - was sailing as navigator.

W M Nixon casts an eye back over the 2014 race, whose prize-giving took place in Hobart yesterday, and then concludes by taking us back to 1991, when Ireland moved top of the league in the Offshore Racing World Team Championship on the same occasion some 23 years ago.

It has to have been the most keenly-anticipated debut in recent world sailing at the top level. At last we'd get to see how Comanche could go in serious sailing. When the 70th 628-mile Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race started on Friday December 26th at 0200 hours our time, 1300 hrs local time in Sydney Harbour, this was for real. There may have been 117 boats of all shapes and sizes from 33ft to 100ft in the fleet. But all eyes were on the limit-pushing 100ft Comanche, skippered by the great Kenny Read. The world wanted to see how she would show what she could do when the chips were down, when the racing was straight line stuff, and when some serious offshore battling was in prospect instead of the inshore-hopping mini-test which had been seen in the Solas Big Boat Challenge in Sydney Harbour on December 9th.

In that, the well-tested Wild Oats XI, skippered by Mark Richards, had sailed a canny race to take the line honours win from the other hundred footers. But the majestic Comanche, owned by Jim Clark and his Australian wife Kristy Hinze Clark, had shown enough bursts of speed potential to raise the temperature as the start of the big one itself approached.

And in a brisk southerly at the start, Comanche didn't disappoint. She just zapped away from Wild Oats to lead by a clear 30 seconds and notch a record time at the first turning mark to take the fleet out of Sydney Harbour, and that dream debut was what made the instant headlines on the beginning of the 628–mile slog to Hobart.

The moment of glory – the mighty Comanche roaring down Sydney Hobart at the start to log a record time to the first turning mark. Photo: Rolex/Daniel Forster

No two ways about it – Comanche is clear ahead of Wild Oats XI approaching the first mark. Photo: Rolex/Daniel Forster

But out at sea, with winds strengths varying but mostly from the south for the first day or so, different stories begin to emerge. A grand sunny southerly sailing breeze may provide lovely sailing and pure spectacle in Sydney Harbour. But get out into the Tasman Sea to head south for Hobart, and you find that the wayward south-going current – always a crucial factor in the early stages of the race to Hobart – can be going great guns and making mischief as a weather-going stream, kicking up a steep sea which can be boat-breaking when that last ounce of performance is being squeezed out.

And as previewed here on December 20th, up among the hundred-footers they've been pushing the envelope and then some in boat development and modification. In new boat terms, the mighty and notably beamy Comanche has gone about as far as they can go for now. But with the likes of the former Lahana reappearing as Rio 100 with a complete new rear half, and Syd Fischer's Ragamuffin 100 simply cutting away the hull for replacement with a complete new body unit while retaining the proven deck and rig, we're sailing right on the edge in terms of what the weird mixtures of new and old build can combine for combat when the seas are steep.

Comanche's wide beam gives added power when there's plenty of breeze......Photo: Rolex/Carlo Borlenghi

....but the narrow Wild Oats XI can be as slippery as an eel when the head seas get awkward, and when the wind eased she got through Comanche and into an extraordinary 40 mile lead on the water. Photo: Rolex/Carlo Borlenghi

Not all boats revelled in the bone-shaking conditions of the first hundred miles of beating. Perpetual Loyal (foreground) had to pull out with hull damage possibly caused by an object in the water, but the irrepressible Syd Fischer's Ragamuffin 100 (beyond), with a completely new hull, continued going strong to the finish and was third in line honours Photo: Rolex/Carlo Borlenghi

But this glorious element of larger-than-life characters with boats that are off-the-wall is now an integral part of the RSHYR, which manages to attract an enormous amount of attention thanks to its placing in the midst of the dead of winter in the Northern Hemisphere, while in Australia much attention focuses on what is in effect an entire and familiar maritime community racing annually for the overall handicap prize.

Yet though the course is simple, it's deceptively so. Just because it's mainly a straight line from one harbour to another doesn't mean there aren't a zillion factors in play. And as the race gets so much attention, few offshore events of this length are so minutely analysed, and the first 24 hours provided a veritable laboratory for seeing the ways different boats behave in different wind and sea states with the breeze on the nose.

Thus Wild Oats XI has always had a formidable reputation for wiggling her exceptionally narrow hull to windward in awkward seas for all the world like a giant eel, and the early beating saw her doing that very thing, hanging in there neck and neck with Comanche. Despite her beamier hull, Comanche rates slightly lower than Wild Oats. But if a lull with its leftover sea arrived, her greater volume would become a liability to performance, whereas if the breeze got back to full strength, and particularly if it freed the two leaders, then Comanche would be firmly back in business.

But it was not be. Crossing the Bass Strait with Wild Oats right beside them, Comanche's crew saw their navigator Stan Honey emerge on deck and approach Kenny Read with a thoughtful expression on his face, and an ominous little slip of paper in his hand. It was the latest weather print-out, and it wasn't happy reading for a big wide boat that needs power in the breeze. Before expected brisk winds from the north set in, they'd to get through the lighter winds of an unexpectedly large and developing ridge.

Almost while they were still digesting this bit of bad news, Wild Oats started to cope much better with the lumpy leftover sea, and wriggled ahead of Comanche in her classic style. And the further she got ahead, the sooner she got into increasingly favourable wind pressure. As Read put it after the finish: "For twelve hours, conditions were perfect for Wild Oats, and they played a brilliant hand brilliantly".

Amazingly, the old Australian silver arrow opened out a clear lead of an incredible forty miles before conditions started to suit Comanche enough to start nibbling at this remarkable new margin. And fair play to the Read crew, at the finish they'd made such a comeback that Wild Oats was only something like 49 minutes ahead. But even with the new American boat's slightly lower rating, she was beaten on handicap too, and in the final rankings Wild Oats showed up as having line honours overall and a commendable 5th on IRC in Division 0 - and we shouldn't forget she won the overall handicap honours back in 2012 anyway.

But for 2014's race, for a while it looked as if it might be the Cookson 50s again for the overall win. But although last year's Tattersall's Cup winner, the Cookson 50 Victoire, at first took the Division 0 win with her sister-ship Pretty Fly III second, they were so close that when Pretty Fly got 13 minutes redress for an incident with the Ker 46 Patrice in mid-race, it reversed their placings.

It all came good in the end....after being initially placed second in Division 0, the ten-year-old Cookson 50 Pretty Fly III got 13 minutes of redress for an adverse incident during the race, and that bumped her up to the Division 0 win.

Either way, it was still Cookson 50s imprinted all over the sharp end of Division 0. But they were slipping in the overall rankings, where it was boats in the 40-45ft range which were settling into the best combination of timing and conditions to take the Tattersall's.

And plumb in the middle of them was the First 40 Breakthrough, with her strong Dublin Bay Sailing Club input from the Irish team led by Barry Hurley. Fortunes wax and wane with astonishing volatility as the Hobart race progresses, but gradually a pattern emerges. So though at one stage Breakthrough was showing up only around 30th overall, equally she'd a best show of third.

And all around her on the water were similarly-sized and similarly-rated boats with their race-hardened crews knowing that with every mile sailed and every weather forecast now fallen favourably into place, things were looking better and better for this group to provide the overall winner.

It was a very race-hardened crew which came out on top. It was way back in 1993 that Roger Hickman got his first Sydney Hobart Race overall win in an eight year old Farr 43 which was still called Wild Oats, as original owner Bob Oatley hadn't yet reclaimed the name for ever bigger Grand Prix racers. When he did start to go down that road, the 1985 Wild Oats became Wild Rose, but "Hicko" still owns her. And by the time the Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race 2014 started, he was doing it for the 38th time. He went into it as current Australian Offshore Champion, now he has won the big one on top of all that. Some man, some boat.

The slightly higher-rated Breakthrough was pacing with Wild Oats for much of the race, but as Barry Hurley's report for Afloat.ie told us with brutal honesty, somewhere some time they got off the pace. If you didn't know already of Barry's remarkable achievements - which include a class win in the single-handed Transatlantic Race and the more recent Middle Sea Race success – you would warm to the man anyway for the frankness of his initial analysis of why Breakthrough slipped from being a contender to 12th overall and – more painfully – down to 7th in their class of IRC Division 3.

He promises us more detailed thoughts on it in a few weeks time, something which will be of real value to everyone who races offshore, for the race to Hobart is a superb performance laboratory. And maybe we can also hope in due course for further thoughts from someone on whether or not Matt Allen's Carkeek 60 Ichi Ban, skippered by Gordon Maguire with Adrienne Cahalan as navigator, has what it takes to be a killer.

It's easy for us here in Ireland to look at screens of photos and figures and reckon that Ichi Ban is just a little bit too plump for her own good. But Maguire has twice been key to a Sydney-Hobart overall win, the most recent being in 2011 with Stephen Ainsworth's Loki. And Cahalan's record of success as a navigator/tactician is almost without parallel. Yet though Ichi Ban's 2014 Hobart race score of 8th in line honours and fourth in IRC Division 0 is a thoroughly competent result, it just lacks that little bit of stardust.

Ichi Ban finding her way through the waves on her way to Hobart. If that's not a spare tyre around her midriff, then what is it?

Despite being a "racer/cruiser", the Botin 65 Caro – navigated by Ian Moore – pipped Ichi Ban for third in class.

With the next Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race just over eleven months down the line, let's hope we're proven utterly wrong within the year on the Ichi Ban question. But the whole matter is pointed up by the fact that the boat which pipped in ahead of her in the IRC Div 0 placings in third place behind the two Cookson 50s was the Botin 65 Caro, with our own own Ian Moore navigating on this 65 footer which likes to emphasize her dual role as a racer-cruiser.

Now there really is food for thought. But in this first weekend of this wonderful new year of 2015, let's remember some of the events of December 1991 as recorded in excited detail in the Afloat magazine of Feb/March 1992.

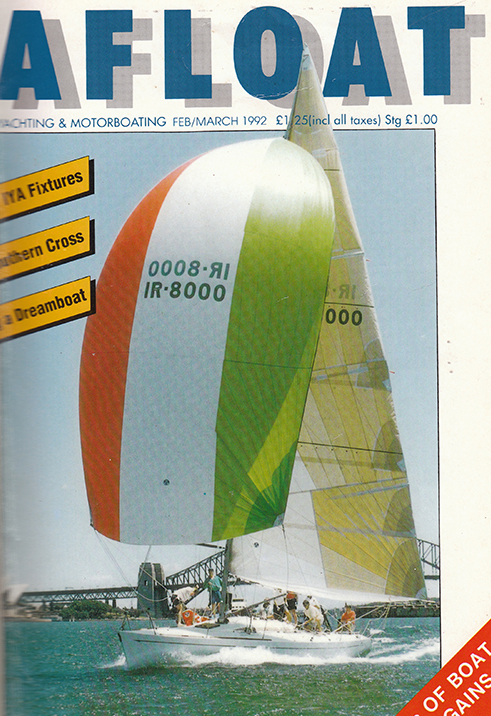

On the cover is Meath-born John Storey's Sydney-based Farr 44 Atara, around which the Irish Southern Cross team of 1991 was built, as Harold Cudmore was aboard, and he brought out John Mulcahy from Kinsale and John Murphy from Crosshaven.

The small boat of the team was Tony Dunne's Davidson 36 Extension – the owner claimed Irishness through the Irish granny rule, but the matter was put beyond any doubt by Joe English being on board with Dan O'Grady and Conor O'Neill. And then for the third boat they'd Warren John's Davidson 40 Beyond Thunderdome, whose owner was happy to be Irish if they'd let him, and to put the matter beyond doubt his vessel was over-run by Howth men in the form of Gordon Maguire, Kieran Jameson, and Roger Cagney, with Dun Laoghaire's Mike O'Donnell allowed on board too, provided he behaved himself.

In the Southern Cross Series of 1991, the Davidson 40 Beyond Thunderdome was raced for Ireland by Gordon Maguire and Kieran Jameson. Thunderdome was top of the points table when she was knocked out with a dismasting in the final inshore race, and was unable to race to Hobart.

It was an accident-prone series, with Beyond Thunderdome dismasted in a tacking collision with one of the Australian boats with just three days to go to the start of the Hobart Race. There simply wasn't time to get a replacement mast, let alone tune it, but at the last minute the jury decided the Australian boat was at fault, and allowed Beyond Thunderdome average points not only for that race in which she'd been dismasted, but also for the Hobart Race which hadn't even yet been sailed.

In a final marvellous twist to the story, as Thunderdome couldn't race to Hobart, Gordon Maguire was drafted aboard Atara to add helming strength for the big one. Atara had only been a so-so performer until the big race. But Cudmore and Maguire – that really was the dream team. And it gave the dream result. Atara won the 1991 Sydney-Hobart race overall by a margin of one minute and 50 seconds. It was one of the closest results ever, but it was a close shave in the right direction for Ireland. The Irish party in Hobart to welcome 1992 was epic. And Gordon Maguire's sailing career was set on a stellar course.

Our magazine edition of February/March 1992 cover-featured John Storey's Farr 44 Atara, overall winner of the 1991 Sydney-Hobart race with the dream team of Harold Cudmore and Gordon Maguire on board to give Ireland the win in the Southern Cross Series.

Seascapes On RTE Radio 1 Has Much To Celebrate After 25 Years

#seascapes – The maritime community in Ireland is a mystery to the vast majority of the rest of the population. Admittedly anyone Irish will sing enthusiastically about how good it is to be entirely surrounded by water. But for most folk among a people who like to think that they're basically rural even if the reality is they're increasingly urban, the sea is seen as no more than a useful barrier, while the coast is only briefly a fun place at the very height of a good summer.

The sea and the coastal interface are not seen as an exciting world in itself, a unique environment which deserves to be explored, enjoyed and utilised in practical and often beneficial ways. On the contrary, the popular view of the plain people of Ireland is that the less they know about the sea, the better. And the unspoken corollary of this is that anyone who seeks to go to sea for recreation is at best a bit odd, maybe even a misfit ashore, while those who work on the sea only do so because they couldn't get a job on land.

Here at Afloat.ie, in its various manifestations over the past 52 years, we've been trying to spread mutual understanding and useful information among the many and varied strands of those who go afloat for sport and recreation in Ireland and beyond. We know this is largely a matter of preaching to the converted. But we also try to do our bit to welcome those who may be newcomers to the world of boats, while remaining keenly aware of the drawbacks of over-selling our sport, our hobby – our obsession, if you wish.

Sailing and boating in Ireland can be rugged enough. Thus the sport in all its forms can only expand in a sustainable way if it attracts people who will themselves bring something positive to the party, for interacting usefully with boats is not a passive affair. And there has been a certain level of success. Over the years, while there was an understandable blip in boating numbers during the recent recession, the graph has been reasonably healthy when it's remembered that rival sport and entertainment attractions are proliferating all the time, while the increasing availability of holidays afloat in sunnier climates makes the promotion of boating activity within Ireland more problematic.

Fifty-two years ago, beginning a process of regular communication among Ireland's recreational boating community was quite a challenge. But it was a very straightforward project compared with inaugurating a regularly weekly broadcast maritime programme for all listeners on national radio in a country notably averse to the sea. Yet it all began 25 years ago, and it's still going strong.

So how do you celebrate 25 years of a niche radio programme, a little Irish maritime magazine of the air? It would be too much to expect a documentary on primetime television. And even an extra-long gala edition on the national radio airwaves at peak listening times might well be counter-productive. So it seems the answer is that the best way to celebrate 25 years of Seascapes on RTE Radio 1 is to publish a book well-filled with some of the key broadcasts with which it has been associated. And as those now-printed broadcasts include a maritime-themed series of the prestigious Thomas Davis Lectures, you mark the anniversary by sending out those as broadcasts again in their own right twelve years after their first transmission.

It may all sound almost devious, a matter of managing to slip the Seascapes celebrations in under the RTE management radar. But those of us who have been banging the maritime development drums for a very long time are well aware that, though the tide is definitely turning, there's still a huge underlying resistance to anything to do with the sea and boats, and it takes an element of cunning to get the message across such that, in time, the people are themselves singing from the same hymn sheet, and thinking it was all their idea in the first place.

But the founder of Seascapes 25 years ago, RTE's Cork reporter Tom MacSweeney, makes your average terrier look like a tired old dog. A sailing and maritime enthusiast himself even though his family had been from a non-maritime background, he had as a child in Cork been inspired by his grandfather's great respect for seafarers, and the vital task they performed in keeping Ireland connected with the rest of the world. He could see the sea all about us, and Cork is the most maritime of cities. So he just kept nagging RTE until they gave him a quarter of an hour once a week back in 1989 to put on a maritime programme for an island nation. And though it has been shifted around in the schedules, it is now a solid half hour every Friday night at 10.30pm, a worthy fulfilment of RTE's public service remit - you really do get a sense of Seascape's nationwide listening community, while podcasts make it more accessible than ever.