Displaying items by tag: wind power

Can Ireland’s Wind Power Drive Modern Trading Ships?

The wind is free. No-one disputes that. But harnessing its power can be a very expensive business, particularly if you’re trying to do it at the top level of international competition writes WM Nixon. Yet at a more mundane level of sailing, with auxiliary sail power working in support of electric main engines, we should surely be able to develop cargo-carrying vessels which can work along the coast of Ireland and across the oceans with a minimal carbon footprint.

Their very existence would increase environmental awareness. And their regular functioning could possibly even include an element of Sail Training in their crewing. With this in mind, in a remote and very special place on the Connacht coast, some ideas and proposals of increasing importance have been developing.

Jamie Young of Killary Adventure Centre in far northwest Galway is one of Ireland’s most experienced seafarers, with his nautical skills allied to extensive aspects of mountain-craft to give him an unrivalled overview both of the realities of seafaring, and the techniques of training and leadership.

With the Adventure Centre’s Expedition Yacht being the alloy Frers 49 Killary Flyer (one of the best boats ever in Irish waters), his knowledge of the waters west of Greenland is unrivalled. And while many expect him to be among the first skippers in his category to circumnavigate Greenland, he says it may be some time yet before that happens, for although the passage on Greenland’s west and northwest coasts is slowly clearing north towards Cape Morris Jessup, the ice on Greenland’s far northeast coast continues to present an impassable challenge.

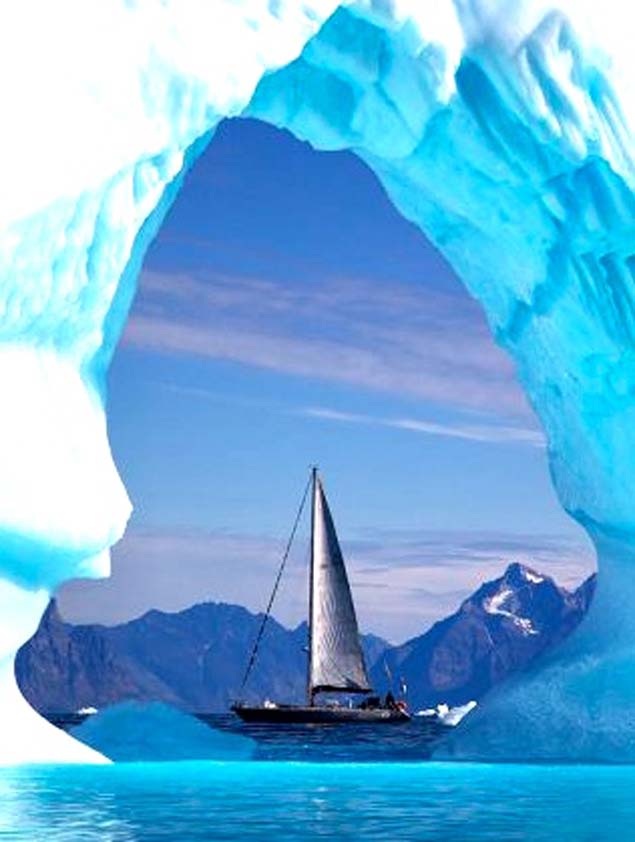

Killary Flyer among the ice of West Greenland. An alloy-built Frers 49, she has been a successful offshore racer (overall winner of the 1988 Round Ireland Race) and a very effective expedition yacht

Killary Flyer among the ice of West Greenland. An alloy-built Frers 49, she has been a successful offshore racer (overall winner of the 1988 Round Ireland Race) and a very effective expedition yacht

But the Greenland challenge and its deeper implications is only one of many items on the Jamie Young agenda. As he mentions in the following article, his extraordinarily varied and extensive CV includes a period when he and his wife Mary were the core professional crew on shipping magnate Huey Long’s Maxi Ondine.

Huey Long was notoriously parsimonious, so much so that we may do an article about it someday, for Don Street is another Irish-connected sailor who had to deal with it. Yet despite his penny-pinching approach, Long accepted that when the big boats from the small but very keen fleet of Maxis wandered the earth alone like dinosaurs in search of top-level glamorous competition, the most economical way to do the lengthy delivery trips was with minimal crew and entirely under engine.

Crews cost money, Maxis were organized to be sailed with large crews, and their sails were ultra-expensive. So the least expensive method of voyaging was to have a substantial auxiliary engine which was installed in such a way that, at the end of a long delivery, it could simply be lifted out and replaced with a new one. This was standard practice. Yet the business of being just two aboard as the big boat thumped her way through all sorts of weather across the empty ocean towards the next big event could be a soul-destroying business.

The Maxi Ondine, skippered by Jamie Young

The Maxi Ondine, skippered by Jamie Young

So not surprisingly Jamie’s enthusiasm for eco-friendly means of getting about the seas and oceans in a commercially and possibly socially-useful manner with a positive reliance on sails easily handled with modern technology has become ever-stronger over the years. He takes up the story:

The Sail Trading Project

By Jamie Young

The pull of the sea is strong and once hooked, it becomes central to your being. Very few of my broad family have or had the faintest interest in the sea, but after my first sail in the late 1950s with one of my cousins, I was hooked.

That cousin happened to be Wallace Clark, renowned for his definitive book about cruising round Ireland. But back in the 1950s, Sailing Around Ireland was yet to be published (it first appeared in 1976), and I was just a small boy who’d been brought along with adults to be taken for a sail somewhere off the coast of Northern Ireland, a small boy who was simply put under the foredeck of the daysailer on which this family obligation was being fulfilled. Yet I became hooked on sailing because of it.

What followed was a continued fascination with the sea and voyaging in various capacities and places: sea kayaking around Cape Horn; sailing Blondie Hasler’s special junk-rigged Folkboat Jester to the USA with Mary for our honeymoon; working as Skipper on the Maxi Ondine on many oceans; solo participant in another engine-less boat in the ’76 OSTAR - and solo return; the AZAB to the Azores and back; the Three Peaks; and many other voyages that I felt lucky to be able to enjoy, including more recently two to the West Coast of Greenland.

Man of the mountains, man of the sea - multiple adventurer Jamie Young of Killary. He feels that traditional sail training may have had its day and that to be meaningful, it now needs to be allied to some form of commercial sailing.

Man of the mountains, man of the sea - multiple adventurer Jamie Young of Killary. He feels that traditional sail training may have had its day and that to be meaningful, it now needs to be allied to some form of commercial sailing.

The stories and the reasons that surround these experiences are for another time. But all seem to have led to a specific interest which has led to many queries branching outwards towards an exciting and necessary future in what I call ‘Sail Trading’.

Having been part of the big boat racing circuit - albeit 40 odd years ago - I remain fascinated by the latest racing machines, including short-handed, solo, fully crewed, Round the World, and America’s Cup. Yet I can’t help but wonder why this fast-adapting technology cannot be put to another parallel use, and create efficient cargo sailing/renewable energy combination vessels.

And I would include creating some tech to prevent the increasing prevalence of vessels, sail and cargo, hitting and killing marine life or causing damage to both parties, for although this gruesome image results from a whale and ship collision, does anyone think when an IMOCA 60 at thirty knots is damaged by its keel hitting a whale, that the unfortunate whale is not also seriously and possibly fatally injured?

The tragic result of vessels in a hurry – a fatally injured whale impaled on the bow-bulb of a big ship

The tragic result of vessels in a hurry – a fatally injured whale impaled on the bow-bulb of a big ship

We can no longer have contempt for our natural environment, and as foils increase speeds to be seen as lethal cutting instruments, we should pause for thought…. Since we now have digital Doppler radar that can spot a buoy miles away, where is the responsibility and options to make a positive contribution to sustaining ocean wildlife? As Gandhi said: ‘There is more to life than just increasing its speed’.

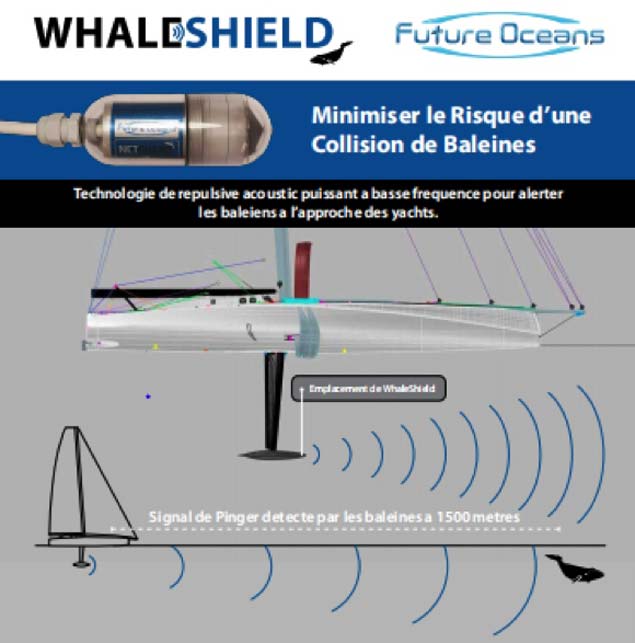

The Future Oceans group have created the Doppler radar Whaleshield

The Future Oceans group have created the Doppler radar Whaleshield

On a more positive note and back to ‘Sail Trading’, there is now a growing effort to consider again using the wind to power cargo vessels and ideally, it’s time for Ireland to get involved as an island nation, bearing in mind the historical trading activity between France and Iberia from Ireland’s west coast, from which the likes of Grace O’Malley and Daniel O’Connell greatly benefitted.

An interesting Irish connection that has blossomed into a regular transatlantic trade - both goods and passengers - is the Brigantine Tres Hombres. She was once a ferry to the Aran Islands from Galway in the ’70s and called Boidin. But she did start her life in the Baltic, and I am sure has many stories buried in the woodwork of her long life. She was discovered abandoned in Galway docks, towed back to Holland and slowly rebuilt to modern standards into the vessel you see today.

The commercial sailing ship Tres Hombres is the former Aran islands ferry Boidin

The commercial sailing ship Tres Hombres is the former Aran islands ferry Boidin

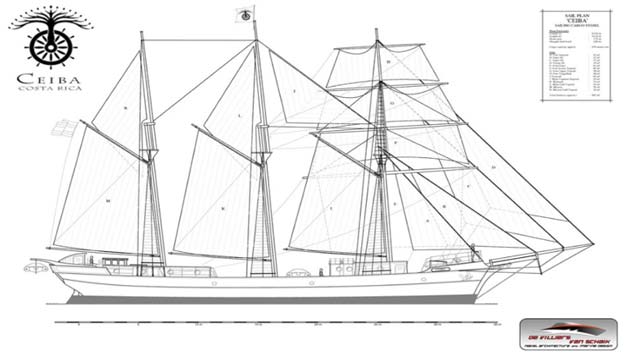

There are encouraging new builds, with some based on traditional lines as in the project CEIBA in the jungles of Costa Rica. This is fast taking shape, the difference being that she will have an electric auxiliary motor powered by renewables. The pictures show what the outcome will be, and she is now framed with the photo showing the full size lofting floor beside her present build. Her trading plans are more local to Costa Rica and around the Gulf of Mexico, but who knows what more distant opportunities may arise.

The Costa Rican Three-Master will be run as a commercial trading vessel

The Costa Rican Three-Master will be run as a commercial trading vessel The Costa Rican three-master is in build in traditional timber style

The Costa Rican three-master is in build in traditional timber style

There are also a number of forward-looking projects that are looking at new technologies or adapting existing ones and these are equally fascinating. Energy Observer was originally a Nigel Irens catamaran from 1983, perhaps best known as ‘ENZA New Zealand’ when Sir Peter Blake and Sir Robin Knox Johnston set records with her. After only just returning from an initial round the world, she has been lengthened and further adapted for another four-year circumnavigation using purely renewables, while most interestingly creating hydrogen via solar as part of the motive power, which will also be augmented with rotating sails which are called ‘Oceanwings’:

Originally the Nigel Irens catamaran ENZA New Zealand, Energy Observer has been lengthened for a second circumnavigation entirely using renewable energies and her oceanwings rotating sails

Originally the Nigel Irens catamaran ENZA New Zealand, Energy Observer has been lengthened for a second circumnavigation entirely using renewable energies and her oceanwings rotating sails

More interesting again are two orders for sail-assisted large cargo vessels for a particular transatlantic route, mainly machinery deliveries. The first build is recently announced and under way from Neoline:

Two of these sail-assisted large cargo vessels from Neoline are currently in build

Two of these sail-assisted large cargo vessels from Neoline are currently in build

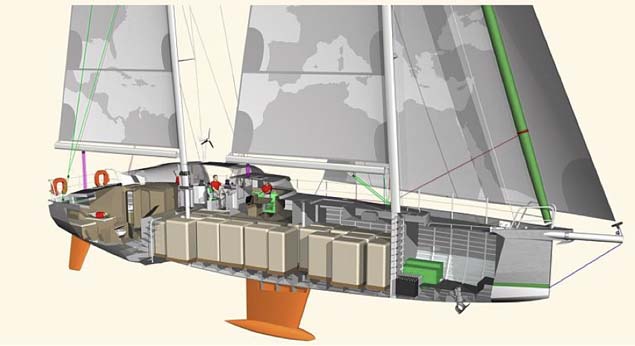

What I am most interested in initially is the build and operation of a multi-use sail trading vessel based on the current Votaan 72 example under construction in France. This is being built in the Alumarine-shipyard at Saint-Nazaire, near Lorient in Brittany.

The Votaan 72 is planned to have a 35-ton cargo capacity - 72 feet long - made of aluminium so minimum maintenance costs - nearly 100% recyclable - Two masts - 4 crew.

The Votaan 72 is building in France in aluminium

The Votaan 72 is building in France in aluminium

This project is of a size and scale that makes it possible from several directions: finance - maintenance - crew - access – materials. And it shows that with breadth of vision, we can think of it in multi-use terms. And what does ‘Multi-use’ mean? To make this a viable enterprise in the first instance, the roles envisaged would be:

- Cargo vessel between set ports on a common route. This might suit a corporate body that is prepared to ship by ‘traditional’ means and benefit from this exposure - with professional marketing input.

- As a marketing tool for a selection of companies to different ports where a mini ‘trade show’ can be held - again with professional marketing input - at those chosen destinations.

- As exposure to the sea for trainees not just from a traditional perspective of sea time, but access to transferable skills more modern in nature - and skills not confined to the marine sector.

- These skills would consist of: use of the comprehensive digital tools now available to mariners - interspersed with use and understanding of traditional methods of navigation and weather forecasting - and dealing with life on board out of sight of land and with no TV/internet…..

- This process could be increased by having the ability to adapt the vessel from a crew max of 6 on regular routes, while also adapting the cargo area to a max of 12 passengers on more defined sailing experiences.

- This would be all about the spirit of adventure and youth development, but with a modern twist that could include the transferable skills mentioned.

- Part of this would, therefore, be the ability to ship at set times the adventure sports equipment which allows for shore experiences. (Kayaks - camping - photography - etc.), and the possibility of research projects that can contribute to the development of further climatic solutions.

- Encourage a program of plastic & general rubbish collection on some of Ireland’s more remote coastline locations and islands.

The Votaan 72 cargo space can be re-purposed to provide extra crew accommodation

The Votaan 72 cargo space can be re-purposed to provide extra crew accommodation

With some regret, I am further of the opinion that traditional sail training or personal development style voyages and ships, while they have their place, are not where the future lies in this area, and certainly not in Ireland. We have to excite and encourage by osmosis and foster a lifelong interest in all things maritime, including an interest in adopting new technologies in other areas that lessen mankind’s climate footprint.

There may be other such uses, but the initial emphasis will be on variety while the project crystallises. This is based on the first instance, however, it is planned, that once the concept stabilizes, a more complete and structured program will emerge.

Because this concept is what you could call a “Re-emerging Trend”, with the correct business structure it is possible that after a number of years the vessel would be sold on and another ‘improved’ version built. Maybe: bigger - more efficient - using now established cargo routes - re looking at possible technological advantages - looking towards new and/or different markets.

FINANCE

The overall monetary concept is to create a self-financing model of operation, and indeed - in time - to make it a profitable enterprise. This will require accountancy skills way beyond my level of competence, however, though I might have notions…!

As my Arctic sailing vessel ‘Killary Flyer’ is presently berthed at the friendly and efficient Mooney’s Boatyard in Killybegs, whenever I visit I am amazed at both the size and complexity of the huge fishing vessels moored up. Never mind the international examples raping the west coast on ‘MarineTraffic’, surely there must be a financial lesson there?

Thus, there are a couple of models to consider:

- Tax-efficient trading company based on purely commercial considerations, suitable for corporate investment. Trading with varied high-value cargo - not time-specific between set ports.

- Sourcing funds from an EU project. These might be a little light in view of current circumstances globally…

- Crowdfunding to the Irish - and other - diaspora. This is a comparatively new method of raising funds, but with my purchase of an electric bike via Indigogo last year - where they managed to raise €16M – it certainly provides food for thought.

- And crowdfunding comes - as far as I am aware - in two styles: creating a product that funders get at a discount when successfully launched – it’s basically seed money.

- Or where the visuals/story created are the story, which is funded via regular online postings. It is now longer possible to ‘disappear over the horizon’ thus, as Point F above, one of the skill sets to be developed by groups is social media engagement. With new satellite launches now regular and Inmarsat/Iridium prices falling, it is expected this would be a key tool of contact and interest in real-time.

- The purpose of this project/article, therefore, is to demonstrate that we are on the cusp of further strong sea transport evolution and Ireland should get on board and use its island position to develop this capacity and help benefit and encourage some of the youth of today, in an economical and affordable manner.

As the author, I intend to work away at the concept and believe this article will prompt others to get involved and I would encourage any reader to get in touch with queries - ideas - and help with the financials… Most of my ideas, whether it was sailing to Greenland or sea kayaking around Cape Horn, or indeed setting up a business in the west of Ireland during the ’80s, were greeted with astonishment. But here we are….

Nothing is set in stone at this stage and I am always receptive to solid worthwhile input, indeed I thrive on it.

Do we want to be one of the leaders of the pack in both modern youth engagement and exploring small vessel renewable trade?

Dublin Array Developer Applies for Foreshore Lease

A foreshore lease application has been lodged for a series of offshore wind farms in Dublin Bay.

The Dublin Array, to be situated on the Bray and Kish Banks some 10km from the coast, would consist of 145 turbines, each 160m high, operated by Saorgus Energy Ltd.

The project has been criticised by the Coastal Concern Alliance due to its approval in contravention of an EU directive that requires a strategic environmental assessment.

Further details are available at www.saorgus.com and www.coastalconcern.ie.

World's Largest Kite-Powered Vessel On The Way

Cargill Ocean Transportation has signed on with an innovative new company to launch the world's largest ever kite-propelled vessel. (Scroll down for Video)

The Hamburg-based company SkySails claims its technology can generate enough propulsion to reduce fuel consumption by up to 35% in ideal sailing conditions.

SkySails' system uses a computer-controlled kite connected by rope, flying between 100m and 420m in a figure-of-eight. The auomated system steers and adjusts the kite to maximise the wind benefits and requires minimal action by crew.

At the end of this year Cargill plans to install a 320sqm kite on a chartered handysize ship with a view to full operation by early 2012.

The firm intends to partner on the project with "a shipowner supportive of ennironmental stewardship in the industry".