Displaying items by tag: Alfred Mylne

Ireland’s Leading Creator Of One-Design Racers Was The Very Scottish Alfred Mylne

We’re accustomed to thinking of successful and long-lived local One-Design keelboat classes as being a distinctive feature of Irish sailing. Thus we tend to overlook the fact that one particular Scottish designer created more of these Irish boats than anyone else. But as a majestic new tome about the life and works of Alfred Mylne (1872-1951) reminds us, this talented visualiser of enduring timber-built classics and Irish One-Designs was Scottish to the core. Yet while we might like to think of him as being energetic in the Irish One-Design cause, most of the creativity emanating from his Glasgow design office was devoted to ensuring a steady stream of work – preferably with substantial one-off vessels - for his company’s boatyard, which was run in conjunction with his brother Charles on the accessible island of Bute in the Firth of Clyde.

In today’s world of classics in the international sailing scene, Mylne is mainly renowned for decades-long production of elegantly distinctive and sometimes very large sailing yachts, the survivors now in an exquisitely restored or even virtually re-built condition. So inevitably this mega-book, by Alfred Mylne archive-holder and company owner David Gray and journalist Neil Lyndon - with input from sailing historians including Clare McComb - is primarily aimed at the current proud owners of the great Mylne classics which still sail the sea.

He may have looked like everyone’s easygoing favourite uncle, but Alfred Mylne was an ace helmsman who designed superb boats

He may have looked like everyone’s easygoing favourite uncle, but Alfred Mylne was an ace helmsman who designed superb boats

EACH GREAT MYLNE CLASSIC DESERVES FOUR COPIES OF THIS BOOK

Each of them should have at least four copies even if they are selling through Amazon at €105 each, though there’s special treatment for Afloat.ie readers during March (see details below). For four is only the most basic requirement, as you’ll need one for home, another for the office or board-room, a third one for the yacht herself, and a fourth for your stylish harbour-side pied-a-terre.

In putting the case for Mylne, the book doesn’t pull its punches. Lavishly illustrated both with historic (and marvellous) photos and carefully-prepared versions of original drawings, it uses high-quality paper (i. e. exceptionally heavy paper) in order to do full justice to all the many illustrations throughout its 498 pages. Consequently, it clocks in at a fighting weight of 3.10 kilos on outside dimensions of 297 X 270mm, which is 6.83 lbs and as near as dammit a foot high by eleven inches wide in old money.

HEAD-TO-HEAD WITH G L WATSON?

This means that weight for weight and size for size, it goes exactly head-to-head with the G L Watson book by Martin Black published by Hal Sisk’s Peggy Bawn Press in Ireland in 2011. And the rivalry doesn’t stop there, for the only time the normally mild-mannered Alfred Mylne had a conspicuous falling-out with anyone came when – as assistant to G L Watson for the unsuccessful and very fraught 1895 Dunraven America’s Cup Challenge with Valkyrie III in New York – he bore much of the brunt of a previously unmanifested unpleasantness to Watson’s character, so much so that by 1896 he’d parted from Watson and set up his own yacht design office in Glasgow, aged just 24.

The eventually successful longterm outcome of that move – made initially with virtually no resources – is proudly recounted in a book which doesn’t hold back in relation to the comparable reputations of Mylne with both G L Watson and William Fife of Fairlie, who was the third member of that extraordinary creative yacht design trio in Scotland, as its full title is “Alfred Mylne: The Life, Yachts and Legacy of Scotland’s Greatest Yacht Designer”.

Britannia with the Scottish Islands OD Shona. This image sums up the diversity of Mylne’s career. He worked on Britannia’s original design in the G L Watson office in 1892-93, then when it became time to convert her to Bermuda rig, he did that challenging design work in his own independent office, and meanwhile his interest in local sailing was such that he took a special interest in his design for the Scottish Island ODs in the late 1920s.

Britannia with the Scottish Islands OD Shona. This image sums up the diversity of Mylne’s career. He worked on Britannia’s original design in the G L Watson office in 1892-93, then when it became time to convert her to Bermuda rig, he did that challenging design work in his own independent office, and meanwhile his interest in local sailing was such that he took a special interest in his design for the Scottish Island ODs in the late 1920s.

Quite. That’s telling them, and no mistake. And as Watson died suddenly in 1904, worn down by an extraordinary workload at the early age of 54, while Fife departed this world in 1944 at the age of 87 with Mylne exiting in 1951 aged 79 and – like Fife - after a brief retirement, you might reasonably think that after 72 years it should now be possible to make a dispassionate assessment as to just who was tops in this extraordinary triumvirate of exceptional Scottish maritime creativity.

OWNERS’ SPECIAL DEVOTION TO “THEIR” DESIGNER

But the fact that classics from their three main design boards still sail the seas with the greatest elegance means that the owners quite rightly have a special devotion to their own particular designer, with Watson perhaps tops for sheer speed, Fife for overall elegance and pure quality and completeness of finish, and Mylne for good all-round handsome seaworthy boats with which you felt comfortable, and more than a few of which proved faster than any of his rivals’ contemporary craft.

In Ireland with so many One-Design boats in his name, Mylne is very much the main man, even if we allow for the style of William Fife and the talent of G L Watson, particularly as manifested in Hal Sisk’s superbly-restored 1894 Hilditch of Carrickfergus-built Watson cutter Peggy Bawn.

Nevertheless it is thought-provoking to realise what a relatively small part the One-Designs played in the Mylne story’s bigger picture. This is something which at times was reinforced by the fact that while Mylne may inevitably have experienced inter-personal difficulties dealing with some very rich customer of a diva tendency with a large dreamship in mind, he could equally find himself arguing some minor matter with pernickety owners of Irish One Designs who would occasionally by-pass their Class Secretary in seeking the designer’s attention.

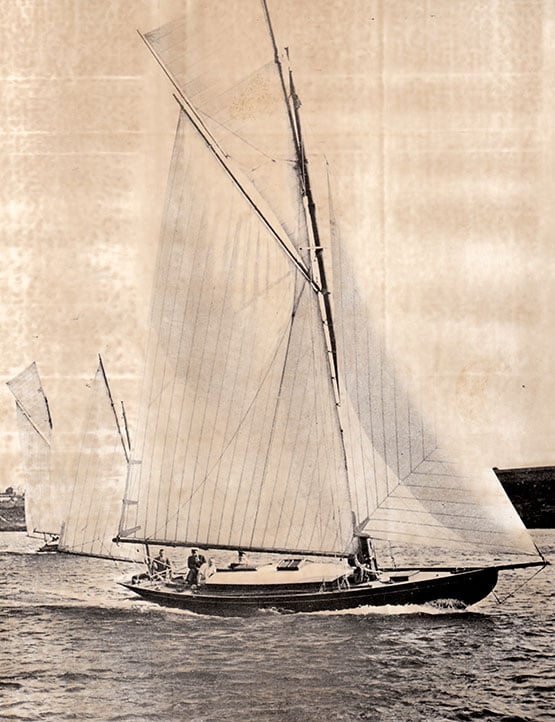

Busy man. When Alfred Mylne was designing Kelpie (above) for the new South Coast One Design Class in 1902, he was also finalising the design for the new Dublin Bay 21s

Busy man. When Alfred Mylne was designing Kelpie (above) for the new South Coast One Design Class in 1902, he was also finalising the design for the new Dublin Bay 21s

Yet apart from his long-gone spat with G L Watson, Mylne was noted for his courtesy and quiet good company, and if his profile hasn’t until now reached the Fife or Watson heights, it’s because he was a modest man who preferred to let the quality of his work speak for itself.

BOOM-TIME GLASGOW

The book of the Mylne story is largely in chronological form, but in the absence of documentation through a lack of early family papers, and the fact that when the office in Glasgow was moved to new premises much paperwork other than drawings was dumped, in the early chapters there has to be a certain element of creative placing of the young Mylne in the engineering and ship-building milieu of the rapidly-expanding Glasgow of his youth and young manhood.

It was a booming hyper-busy and extravagantly confident place, where the status of Naval Architecture was eventually to receive recognition with the establishment of its own Department in Glasgow University. But by then young Mylne had done some training as an apprentice with heavy engineering and ship-building firms.

WATSONS’S CHALLENGE

However, after G L Watson established the first independent yacht design office in the world in Glasgow in 1874, as success gradually came the Watson way he started hinting to the city’s promising young design talents with a sailing background that while any reasonably competent designer could create ships and machinery, it took extra skill, talent to the point of genius, and sheer dedication to break into the yacht design market.

By this stage Watson’s workload was increasing exponentially as the Glasgow area’s economy soared, but he knew the money to be made could be basic enough, and hard earned. So his motto was that the firm made its bread from designing racing yachts whose success established his name, but the design group made its bread and butter from designing large sailing cruisers, and it made its bread, butter and jam from creating an extremely impressive range of large and astonishingly good-looking steam yachts. These were at first for local customers, then for the wider UK and Europe, and finally - and most profitably - for American squillionaires.

Thus by the time the young Mylne – having been recruited to the Watson office as a draftsman/designer in 1892 – was chosen to be Watson’s right-hand man during the Valkyrie III America’s Cup Challenge in New York in the city’s typically humid late-summer heatwave of 1895, it was to find priorities were many, varied, and extremely demanding.

His boss Watson – who had crossed the Atlantic in some luxury while Mylne’e travel arrangements were extremely basic – was much taken up with finalising the contracts for two giant steam yachts while staying in the potential clients’ palatial and cool Long Island mansions. Meanwhile the relatively unsophisticated young Mylne was suffering in the exhausting heat and damp around New York Harbor, trying to make an input into the preparation of Valkyrie III in a city which was determined that the big Scottish-designed-and-built cutter wouldn’t win.

Valkyrie III in pre-race mode off New York Harbor in September 1895.

Valkyrie III in pre-race mode off New York Harbor in September 1895.

DUNRAVEN WITHDRAWS IN MIDST OF AMERICA’S CUP

It was a conclusion soon shared by Valkyrie’s Irish owner Lord Dunraven. He pulled Valkyrie III out of the light weather two-boat series after two races, claiming that the large, raucous and very partisan spectator fleet kept crowding his boat in a way that had a markedly adverse effect on her performance.

In the toxic atmosphere which ensued, the un-healed rupture between Watson and Mylne was maybe the least of the problems. But while Dunraven’s very public row eventually had the happier outcome of allowing Thomas Lipton to launch his peace-making 1899 America’s Cup challenge through the Royal Ulster YC, Alfred Mylne was now determined to go it alone and build his own career to the highest level, although it has to be said that subsequently, when very occasionally invited to submit proposals for an America’s Cup challenger, it emerged as an area he preferred to avoid.

HEART IN LOCAL SAILING

For the endearing thing about him is that although he learned to deal with some extremely rich and high-powered clients seeking large yachts, his heart was in local sailing and the clubbability of boats which could be raced by amateur crew. This meant that he devoted more attention to the Irish and other One-Design commissions than they merited from a commercial point of view, justified by the hope that today’s One-Design owner might become tomorrow’s owner of a larger and more profitable cruiser-racer. Be that as it may, so fond was he of regular evening club racing that for a while, through not having a boat to his own design readily available, he was happy enough to own and successfully race the Clyde 23/30 Maudie designed and built by Fife.

Subsequently, the changing environment of the emerging new International Rule in 1907 provided him with fresh opportunities to create new competitive craft for a clientele drawn initially from among his wealthier sailing friends, and from acquaintances made while working with Watson. Not only was it good for business, but it also meant good boats to the old rule became available for re-purposing as cruiser-racers, and Mylne’s longest-owned personal pet boat was his own-designed 1904-built 40ft LOA Clyde 30 Medea, which he was still cruising – and occasionally racing – when he retired from yacht design in 1946.

By that time, he’d had an extraordinary career, as the advent of that new 1907 rule (into which he’d made a technical input) unleashed a spate of orders for the new Metre Class boats. And while the smaller craft of the 6 Metre and 8 Metre classes were the most numerous, inevitably the glamour of the significantly larger 15 Metres and 19 Metres attracted most interest, with the 15 Metres proving to be the ideal combination of impressive size and style to be the focus of popular attention with highly competitive and affluent owners.

The International 15 Metres became the main focus of public interest after the new rule was introduced in 1907

The International 15 Metres became the main focus of public interest after the new rule was introduced in 1907

WILLIAM BURTON, OWNER-SKIPPER SUPREME

One of these was William Burton, a go-getting East Anglian sailing man who, unlike the tough heavy-engineering and ship building tycoons from whom Mylne received his big yacht commissions in Scotland, was much more inclined to the apparently gentler world of the wholesale and retail consumer trade in his success as a rising foodstuffs pharaoh and confectionary king.

But money knows no industrial hierarchy, and Burton could be as tough as they come in commissioning a boat. As for his helming skills, they were so highly regarded that although he’d had some of his most notable victories with his own Mylne-designed 15 Metre boats, when Thomas Lipton’s 1914 America’s Cup challenge with the Charles Nicholson-designed Shamrock IV finally reached the launching stage, Burton was nominated as the helmsman, and for the time being transferred his enthusiasm to the considerable talents of Nicholon, which was something of a blow to Mylne at both a professional and personal level.

However, the outbreak of World War I in 1914 postponed the America’s Cup racing until 1920. By then, all had changed, including the fact that pre-War, Mylne had been building up a very useful clientele in Germany. This had been a situation which enabled him to expand into Norway as well, and as that rugged Scandinavian country - a free nation since 1905 - was to remain neutral during the Great War of 1914-18, its sailing continued and developed to such an extent that it became a safe haven for the continuing survival of some of the formerly Scottish-owned top boats.

Activity at this glamorous international level meant that Mylne’s relatively low-key creation of successful local One-Designs registered less in popular attention, except in the area where they were raced. But nevertheless although this new book is largely chronological in form, it would have been helpful if a chapter had been devoted exclusively to this aspect of Mylne’s design work.

The River Class celebrating their Centenary in Strangford Lough in 2021. The first OD Class in the world to set Bermudan rig, in 1921 they also were Alfred Mylne’s first design project to provide a boat appropriate for post-war conditions

The River Class celebrating their Centenary in Strangford Lough in 2021. The first OD Class in the world to set Bermudan rig, in 1921 they also were Alfred Mylne’s first design project to provide a boat appropriate for post-war conditions

For the reality is that while the surviving Mylne classics are now to be seen in all the more glossy sailing centres, in fleet terms they’re numerically exceeded by Mylne-designed ODs which have been kept going because they provide such excellent neighbourhood boat-for-boat racing, yet happily are increasingly receiving the classic restoration treatment as people realise that their beloved and manageable boat is also a historical artefact of very special local significance.

MYLNE’S IRISH ONE DESIGNS

The Mylne One-Designs for Ireland provide an excellent representative selection, starting in 1898 when the commission for a new Belfast Lough 20ft LWL class for the Belfast Lough One Design Association will have been extremely welcome for a young designer striking out on his own, and still somewhat starved for commissions.

1898: BLOD Class II (Star Class): 20ft LWL gunter sloops for Belfast Lough, later became gaff sloops setting jackyard topsails, but after World War I ended in 1918, reverted to gunter rig owing to shortage of available crewing man-power.

1902: Dublin Bay 21ft OD, 31ft LOA gaff cutters with complete jackyard topsail rig. This was reduced after sixty years use to masthead Bermudan sloop in 1963-64. The class of seven in Dublin Bay ceased racing in 1986 after cross-fleet damage in Dun Laoghaire Harbour in Hurricane Charlie, but is currently being revived as gunter-rigged sloops in a Class Association project led by Hal Sisk and Fionan de Barra, with building work done by Steve Morris of Kilrush Boatyard in County Clare.

The restored Dublin Bay 21 Naneen – this is the third rig they have set since the class was founded in 1902

The restored Dublin Bay 21 Naneen – this is the third rig they have set since the class was founded in 1902

1910: Belfast Lough Island Class 39ft Yawls built by Hilditch of Carrickfergus. Envisaged as the replacement for Fife-designed BLOD Class I of 1897, they offered a genuine cruising option in addition to remarkably close club racing at Cultra and Bangor. At least two are still preserved as classics.

1921: RUYC River Class (now Strangford Lough Rivers), built in the boatyards of Bute as Hilditch of Carrickfergus had closed in 1913. Hefty yet very handsome 28ft 6ins sloops believed to be the first One Designs in the world to set Bermudan rig, they have renewed their strength at the original 12-boat fleet size to celebrate their Centenary in style on Strangford Lough in 2021.

The 39ft Island Class Yawl OD Trasnagh in 1933 after she had been converted to Bermudan rig

The 39ft Island Class Yawl OD Trasnagh in 1933 after she had been converted to Bermudan rig

1937: Dublin Bay 24ft OD. Originally proposed at a Royal Alfred YC Committee Meeting in 1934 by DB21 sailor Gordon Campbell (Lord Glenavy), the stalled project for a class of 37ft 6ins LOA cruiser-racers was taken up by Dublin Bay SC in 1937, but World War II from 1939-1945 interrupted their construction in Bute. It was 1947 before they first raced off Dun Laoghaire, hut soon were firmly established as the premier class in Dublin Bay.

MYLNE WINS AN RORC RACE

The DB24s provided excellent inshore and offshore racing with such success that in 1963, the DB24 Fenestra owned by Stephen O’Mara (Royal Irish YC) was overall winner of a decidedly stormy RORC Irish Sea Race, seeing off some renowned heavy metal to provide what may well be the only RORC race overall win by a Mylne-designed boat. And their cruising could be equally remarkable, lifting several major Irish Cruising Club awards. They finally ceased racing as a class in 2004 in the hope of being used as the basis of a class restoration project to the highest classic standards, but so far only Periwinkle has returned to Dublin Bay in fully restored form to show what might be done.

The restored Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle. In 1963 a sister-ship, Fenestra, was overall winner of the RORC Irish Sea Race. Photo: W M Nixon

The restored Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle. In 1963 a sister-ship, Fenestra, was overall winner of the RORC Irish Sea Race. Photo: W M Nixon

1946: 25ft LOA Glen Class. During World War II in brief intervals between frantic bouts of naval small craft design and construction, the staff in Mylne’s design office in Glasgow, and Arthur Clapham at the Glen Boatyard on the west side of Bangor in Belfast Lough, were exchanging ideas about an economical multi-purpose One Design with a small cabin, and the Glen OD was the result. Built semi-series production with the hulls upside-down, the project resulted in a total of 37 boats, with the first ten racing initially as the No 1 Class at RUYC until the mid-1960s. By that time, however, strong classes were catering for the bulk of the Glen fleet at Strangford Lough YC at Whiterock, and in Dublin Bay where they were mainly focused around the Royal St George YC.

Quality restorations have now become a feature of the class, and in September 2022 a 75th Anniversary Dinner in Strangford Lough YC celebrated the continuing vitality of a Mylne-designed OD which will be a feature of Irish sailing for very many years to come.

IN FOREFRONT OF POST-WAR RECOVERIES

Thus Mylne, increasingly renowned as the designer of luxurious and ever-larger cruising yachts, proved to be active and successful at the other end of the size scale in getting sailing going again in accessible and affordable One-Designs as the world emerged from the carnage of two world wars.

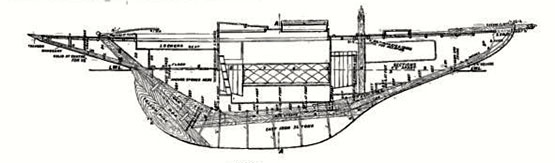

The lines of the economical-to-build Glen Class OD – this was the second time that a World War had inspired Alfred Mylne to create an appropriate post-war “boat for recovery”.

The lines of the economical-to-build Glen Class OD – this was the second time that a World War had inspired Alfred Mylne to create an appropriate post-war “boat for recovery”.

Yet in the bigger picture of his awe-inspiring large craft from the inter-war years – handsome schooners, ketches, yawls and cutters, with every one a stunner – this special Mylne contribution tends to be overlooked, for in 1922 at the age of 49 when everyone assumed he was a perennial bachelor married to his profession like William Fife, he “eloped” to Chichester in the deep south of England with the 29 year old Miriam Brown-Constable of a Cheltenham sailing family, and they returned to Glasgow as Mr & Mrs Mylne, with Miriam proving an able and loyal crew when they had the opportunity to race or cruise Medea.

With her outgoing personality and enthusiasm for sailing, she also made it much easier for Mylne to deal with the social side of promoting his work, and with the Metre Rule up-dated in 1919, visits to Cowes Week were both enjoyable and rewarding. The new rule saw the 12 Metres becoming the sensible class even if the huge boats of the J Class were the most eye-catching, and in Cowes the quietly humorous and gently sociable Mylne was to become firm friend with the ebullient Uffa Fox.

Fox much admired the skill with which the Scottish designer had overseen the conversion of the Royal Cutter Britannia (on which he’d worked as a draughtsman in 1892-93) from gaff rig to Bermudan, and so liked his sea-kindly hull shapes that in one of his famous semi-annual books on yachts and yachting, he featured Mylne’s drawings for the ideal personal yacht, to be called Heart’s Desire. This was a performance cruiser which reflected the fact that Mylne was so genuinely involved in Scottish cruising that in 1929 he had been elected Vice Commodore of the Clyde Cruising Club.

Proper order. William Burton’s Mylne-designed 12 Metre Marina leads the Nicholson-designed Trivia in Cowes Week.

Proper order. William Burton’s Mylne-designed 12 Metre Marina leads the Nicholson-designed Trivia in Cowes Week.

BACK TO BURTON

Meanwhile relations had been re-built with William Burton, and some very elegant 12 Metres resulted, with Marina probably being the most successful. But an attempt by the Burton-Mylne team in 1939 to push the 12 Metre rule to its upper size limit with the 70ft Jenetta – the largest 12 Metre ever built – didn’t make the grade in a season limited by the impending World War II. However, Jenetta has recenty been restored in Germany, and it will be interesting to see how she shapes up on the classic circuit.

The restored 12 Metre Jenetta is a 1939 design, and was the biggest 12 Metre at 70ft LOA

The restored 12 Metre Jenetta is a 1939 design, and was the biggest 12 Metre at 70ft LOA

Mylne was definitely feeling his age through World War II and the need to keep the boatyard going by means of red-tape-strangled Admiralty small ship orders, with their slow if sure systems of payment. But while the yard was eventually sold off, he was encouraged by the fact that his nephew Alfred Mylne II had come into the business by the time he was finalising the designs for the Glen Class to be built in Northern Ireland.

With the succession now secured, Alfred Mylne could finally relax a little and contemplate proper retirement. Miriam persuaded him that he should get away from the Clyde with all its insistent memories good and bad, and live out his senior years in a riverside house in the Cotswolds near her family home.

STYLISH FAREWELL CRUISE

It was quite a change, but they’d an excellent plan to ease the emotional impact of this total changeover. Although the resumption of recreational sailing was only grudgingly permitted in the Greater Clyde area after the war ended in 1945, Mr & Mrs Mylne were always first in the queue to expand their cruising permits, and in 1946 they were finally allowed to cruise more or less wherever they wished with Medea.

The family boat. The 40ft Medea was a several-times-updated Clyde 30 designed by Alfred Mylne in 1904. Although he tried to build himself a replacement in the late 1930s, a canny client let him almost finish the new-build job, and then made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. So Medea remained the family boat, and was passed on to Alfred Mylne II in 1950. Competitive to the end, she was based in 1976 in Ballyholme Bay on Belfast Lough, and sadly was one of the boats which became a total loss in that year’s Great Northeasterly Gale.

The family boat. The 40ft Medea was a several-times-updated Clyde 30 designed by Alfred Mylne in 1904. Although he tried to build himself a replacement in the late 1930s, a canny client let him almost finish the new-build job, and then made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. So Medea remained the family boat, and was passed on to Alfred Mylne II in 1950. Competitive to the end, she was based in 1976 in Ballyholme Bay on Belfast Lough, and sadly was one of the boats which became a total loss in that year’s Great Northeasterly Gale.

But it was already late summer, and it was September by the time they got away for at least three weeks of cruising along the coasts of the highlands and out to the islands. Autumn is not usually a recommended time for cruising the Hebrides, but they made the most if it. Thus Alfred and Miriam Mylne took their departure from the Scottish sailing scene in the same way as they’d been keenly involved in it – with style, enthusiasm and enjoyment.

And in creating this impressive book, this mighty volume, David Gray and his team have done justice to some very special people and their central inspirational genius of Alfred Mylne, whose beneficial influence on Irish sailing lives on and thrives all around us, while his international contribution to sailing with style is now properly assessed.

Alfred Mylne - the Life, Yachts and Legacy of Scotland’s Greatest Yacht Designer is available on Amazon. In the month of March 2023, Afloat readers receive a special discount by using the coupon code: AFLOAT15 on this link here

Historic Belfast Lough Boatyard Lives On Through Classic Yachts

The recreational marine industry is a demanding trade. Your customers buy boats for pleasure, so they assume it’s a fun business to work in. Thus there’s no lack of potential boat designers and builders to be found among the children of those who only sail for sport and fun, for they see that the adults enjoy being around boats, and they get to think that being around boats all the time for work and play is the only way to live.

But in the end, business is business. The bottom line rules everything else. However enthusiastic young people may have been when first going into the boat trade, as they battle on with running their own marine business they find the world of commerce can become a cruel place. W M Nixon considers the challenges of boat-building, and looks at the story of John Hilditch of Carrickfergus, who was one of the brightest stars of the Irish boat-building industry in the golden age of yachting, yet his light was extinguished after barely two decades.

The name of Hilditch of Carrickfergus is synonymous with classic yachts of significant age. John Hilditch built the 36ft G L Watson-designed cutter Peggy Bawn in 1894, and she still sails. In fact, she sails in better shape than ever, as she had a meticulous restoration completed for Hal Sisk of Dun Laoghaire in 2005.

More recently, in 2013 the Hilditch-built Mylne-designed Belfast Lough Island Class 39ft yawl Trasnagh was restored for Ian Terblanche in Devon in time for her Centenary. And in 2015, the Belfast Lough OD Class I Tern – 37.5ft LOA to a William Fife design and built in 1897 with seven sister-ships by John Hilditch - has appeared in Mallorca so superbly restored that when she went on to Les Voiles de St Tropez at the end of September, she won her class despite it being heavy weather, and she only just out of the box.

Peggy Bawn in her first season afloat in 1894. She was built for A J A Lepper, Commodore of Carrickfergus Sailing Club, who was one of John Hilditch’s most loyal clients. Photo courtesy RUYC

Peggy Bawn in her first season afloat in 1894. She was built for A J A Lepper, Commodore of Carrickfergus Sailing Club, who was one of John Hilditch’s most loyal clients. Photo courtesy RUYC

A monumental achievement. All the boats of the new Fife-designed Belfast Lough OD Class 1 of 1897 were built by John Hilditch in less than a year. Photo: Courtesy RUYC

But we don’t have to go to distant restoration specialists to find evidence of the large and varied Hilditch output. The first five boats of the Howth 17 OD class were built by John Hilditch immediately after he’d built the eight Belfast Lough Class I boats. The little new Howth gaff sloops – rigged with huge jackyard topsails as they still are today - sailed the 90 miles home down the Irish Sea to Howth in April 1898, and had their first race on May 4th 1898. All five of the original Hilditch creations continue to race with the thriving Howth 17 class, which today has eighteen boats.

The Howth 17s Aura (left) and Pauline. Aura is one of the original five Howth 17s built for 1898 by John Hilditch immediately after he had completed the Belfast Lough Class I boats. Photo: John Deane

This concentration of yacht design development in a short time span, and through just one boatyard, is rare but not unique – the great name of Charlie Sibbick of Cowes shone equally briefly but even more brightly at much the same time, as he was a designer too. But Sibbick made his name in an established international centre for sailing. Yet when John Hilditch – who was both a seafarer and a fully-qualified shipwright – established his yard at Carrickfergus on Belfast Lough in the winter of 1892-93, the north of Ireland was still a relative backwater in international sailing terms. Thus his achievement is indeed remarkable. For by the time Hilditch closed down in the winter of 1913-14, he had put Belfast Lough firmly in the global picture as a pace-setter in yacht development, and his pivotal role in that transformation is gaining increasing recognition.

Not that there hadn’t been sailing in Belfast Lough before Hilditch came along. There are many yacht and sailing clubs around this fine stretch of sailing water, and the most senior of them is Holywood Yacht Club (on the waterfront below the hills where Rory McIlroy learned to pay golf), which dates back to 1862. And in 1866, two more new clubs came into being – Carrickfergus Sailing Club which was obviously location-specific, and the Ulster Yacht Cub, which became the Royal Ulster Yacht Club in 1869, but was a premises-free moveable feast until 1898, when America’s Cup challenger Thomas Lipton insisted it have a clubhouse, which was duly opened on an eminence close above the Bangor waterfront in April 1899.

The shared foundation year which goes back through the mists of time to 1866 means that both clubs will be celebrating their 150th Anniversaries in 2016. They’ve been quietly working on their separate plans towards celebrating this significant date, with a massive new history of the RUYC under way for a couple of years now and due for publication in the Spring, while Carrickfergus also has plans in the publication line.

Yet although there is much to write about now, in both club’s cases the pace of development was relatively slow until the late 1880s, for until that time, the business of the rapidly expanding city of Belfast was business, and more business. It wasn’t until the 1880s that leisure sailing began to get serious attention from the rapidly growing middle classes of the greater Belfast area. But once they did begin to take it up, they did so with complete enthusiasm, and the sailing pace of Belfast Lough during the 1890s, and on towards 1910, had few rivals.

For the rapid yacht design development seen during John Hilditch’s busy years, compare this with the next image. The old-style hull of Peggy Bawn is revealed as she is lifted out of the Coal Harbour Yard in Dun Laoghaire in 1996 for a first attempt at restoration. Later, Hal Sisk took over the project, and it was completed for him by Michael Kennedy of Dunmore East. Photo:W M Nixon

The new style shape. Although they were built only three years after Peggy Bawn, the Fife-designed Belfast Lough Class I boats had a much more modern hull shape and were primarily racing boats, yet they were required to be well capable of sailing to Scotland and Dublin Bay, and did so

The new style shape. Although they were built only three years after Peggy Bawn, the Fife-designed Belfast Lough Class I boats had a much more modern hull shape and were primarily racing boats, yet they were required to be well capable of sailing to Scotland and Dublin Bay, and did so

Formidable performers. The Belfast Lough Class I boats Merle (6, Brice Smyth) and Flamingo (2, John Pirrie) racing hard in 1898. Both owner-skippers were members of Carrickfergus SC, and based their boats there. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

Formidable performers. The Belfast Lough Class I boats Merle (6, Brice Smyth) and Flamingo (2, John Pirrie) racing hard in 1898. Both owner-skippers were members of Carrickfergus SC, and based their boats there. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

In order to meet this demand, John Hilditch was able to expand his new boatyard at an extraordinary pace. Even then, he couldn’t keep up with demand, such that one new Belfast Lough class, the Linton Hope-designed lifting-keel 17ft LWL Jewel Class of 1898, had to be built in Chester in England. And at the same time, the fishing-boat builder James Kelly of Portrush on the North Coast found that yacht-building to supply the new craze was much more lucrative than producing his own variant of the classic Greencastle yawl for fishermen on both the Irish and Scottish coasts, and he went into yacht-building both for Belfast Lough and Dublin Bay.

But in terms of overall contribution to the transformation of Belfast Lough sailing, John Hilditch was very much in a league of his own. So much so, in fact, that noted international classic sailing polymath Iain McAllister got to thinking last winter that even though no trace whatsoever now remains of this once famous yard, it was time and more for John Hilditch’s work to be celebrated, and how better than a Hilditch Regatta during 2016 to tie in with other Belfast Lough sailing celebrations?

It’s a great idea which seemed almost too good to be true. But thanks to quiet work behind the scenes, most notably by Wendy Grant who recently became Commodore of Carrickfergus Sailing Club neatly in time to hold the top post during the 150th celebrations (she’s the mother of renowned offshore navigator Ian Moore), plus a special sub-committee in RUYC which likewise holds to the notion that the early stages of good work are best done by stealth, a programme is emerging which will keep all organising parties happy while providing participants with a manageable user-friendly schedule.

It has all become viable during this past week thanks to the confirmation that the more distantly-located significant classic boats of the Hilditch oeuvre – Peggy Bawn of 1894, Tern of the 1897 Belfast Lough Class I, the Howth 17s of 1898, and Trasnagh, the Island Class yawl of 1913 – all hope to be in Belfast Lough towards the end of June 2016, where numbers will be further swollen by the Hilditch-built Royal North of Ireland YC Fairy Class of 1902, together with some of their sister-ships from Lough Erne.

The Hilditch-built Tern in a breeze of wind on Belfast Lough, 1898

Tern in a breeze of wind at St Tropez, September 2015.

In addition, the fleet will be increased by other classics of every type, coming together to wish the Hilditch boats well at this special time. And there’ll be a goodly contingent of Irish Sea Old Gaffers which will be heading towards the big event on Belfast Lough in late June by way of the Old Gaffers Rally at Portaferry in the entrance to Strangford Lough from June 17th to 19th.

But before getting carried away by anticipation of all this festivity, let us remember that this week’s thoughts were introduced by a precautionary reminder that the boat-building trade is no bed of roses. So just what did go wrong, that the much-admired Hilditch yard faced closure before the end of 1913, with the man himself dead – perhaps broken-hearted – before the end of 1914?

There seem to be a number of explanations, all of which combine to explain the sudden demise of a great enterprise. The incredible rate of economic expansion in Belfast – which had been accelerating virtually every year since around 1850 – seems to have first shown significant signs of slackening in 1910. The greater Belfast economy did continue to expand in the broadest sense, but the rate of expansion was now slowing.

During the rapid growth years, John Hilditch was able to meet demand, but regardless of the underlying economic patterns, by 1910 his market was beginning to reach saturation levels. If people had continued to change their boats every three years or so – as they’d anticipated doing when the Belfast Lough One Design Association was established in 1896 – then an artificial demand might have been maintained. But people were beginning to realise that a good one design boat was good for much longer than a mere three years. In fact, some argued that a class was only bedded in after three years. So the number of new boats being ordered dried to a trickle.

Yet those boats that were being ordered became individually larger. When the Alfred Mylne-designed 39ft Belfast Lough Island Class yawls began to be conceptualised as the world’s first true cruiser-racer one designs in 1910, they would be far and away the biggest and most expensive one designs Hilditch had yet built. He held out for a price of £350 per boat, but the potential owners – hard-headed Belfast businessmen determined to drive a tough bargain and not to be seen to weaken – wouldn’t budge beyond £345.

In those days, yacht-building was simply priced by overall length, so Hilditch resigned himself to accepting the £345 by agreeing to build a boat with a slightly shorter bow. For all parties, it was a case of cutting off one’s nose off to spite one’s face. The new Island Class yawls were handsome enough. But with a longer bow, they’d have been beautiful.

The island Class yawl Trasnagh, seen here in her first season of 1913, is believed to be the last boat to have been built by John Hilditch. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

The island Class yawl Trasnagh, seen here in her first season of 1913, is believed to be the last boat to have been built by John Hilditch. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

The last of them, Trasnagh herself in 1913, was the last boat to come out of a formerly great yard rapidly tumbling towards extinction. The times were restless politically as well as economically, so it wasn’t a good time to rely on building pleasure boat for a living. And apart from the saturation of the market and the financial demands of building the relatively large Island Class boats, sailing was no longer attracting the same number of newcomers, as rival interests such as motor cars and aeroplanes were taking away many potential enthusiasts,

Yet ironically, had John Hilditch been able to hang on for just another year into the beginning of the Great War of 1914-18, a slew of war work for the Admiralty would have given his yard a new lease of life. But it was not to be. The yard was gone. And soon, so too was the man himself.

But the boats live on. One hundred and two years after John Hilditch’s death, boats that he created are still sailing the seas, and their assembly in Belfast Lough from June 22nd 2016 onwards will be a reminder that, once upon a time, on a site long since covered by Carrickfergus’s re-developed waterfront, John Hilditch and his team built nearly a hundred fine yachts, the best of which have well stood the test of time. All that together with the 150th Anniversaries of two remarkable sailing clubs. For sure, late June on Belfast Lough is going to be one very special time.

Trasnagh restored for her Centenary in 2013