Displaying items by tag: Old Gaffers Rally

Historic Belfast Lough Boatyard Lives On Through Classic Yachts

The recreational marine industry is a demanding trade. Your customers buy boats for pleasure, so they assume it’s a fun business to work in. Thus there’s no lack of potential boat designers and builders to be found among the children of those who only sail for sport and fun, for they see that the adults enjoy being around boats, and they get to think that being around boats all the time for work and play is the only way to live.

But in the end, business is business. The bottom line rules everything else. However enthusiastic young people may have been when first going into the boat trade, as they battle on with running their own marine business they find the world of commerce can become a cruel place. W M Nixon considers the challenges of boat-building, and looks at the story of John Hilditch of Carrickfergus, who was one of the brightest stars of the Irish boat-building industry in the golden age of yachting, yet his light was extinguished after barely two decades.

The name of Hilditch of Carrickfergus is synonymous with classic yachts of significant age. John Hilditch built the 36ft G L Watson-designed cutter Peggy Bawn in 1894, and she still sails. In fact, she sails in better shape than ever, as she had a meticulous restoration completed for Hal Sisk of Dun Laoghaire in 2005.

More recently, in 2013 the Hilditch-built Mylne-designed Belfast Lough Island Class 39ft yawl Trasnagh was restored for Ian Terblanche in Devon in time for her Centenary. And in 2015, the Belfast Lough OD Class I Tern – 37.5ft LOA to a William Fife design and built in 1897 with seven sister-ships by John Hilditch - has appeared in Mallorca so superbly restored that when she went on to Les Voiles de St Tropez at the end of September, she won her class despite it being heavy weather, and she only just out of the box.

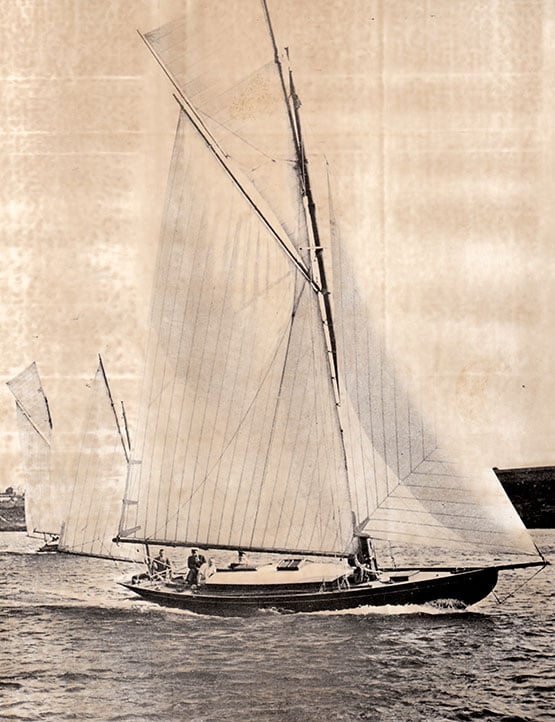

Peggy Bawn in her first season afloat in 1894. She was built for A J A Lepper, Commodore of Carrickfergus Sailing Club, who was one of John Hilditch’s most loyal clients. Photo courtesy RUYC

Peggy Bawn in her first season afloat in 1894. She was built for A J A Lepper, Commodore of Carrickfergus Sailing Club, who was one of John Hilditch’s most loyal clients. Photo courtesy RUYC

A monumental achievement. All the boats of the new Fife-designed Belfast Lough OD Class 1 of 1897 were built by John Hilditch in less than a year. Photo: Courtesy RUYC

But we don’t have to go to distant restoration specialists to find evidence of the large and varied Hilditch output. The first five boats of the Howth 17 OD class were built by John Hilditch immediately after he’d built the eight Belfast Lough Class I boats. The little new Howth gaff sloops – rigged with huge jackyard topsails as they still are today - sailed the 90 miles home down the Irish Sea to Howth in April 1898, and had their first race on May 4th 1898. All five of the original Hilditch creations continue to race with the thriving Howth 17 class, which today has eighteen boats.

The Howth 17s Aura (left) and Pauline. Aura is one of the original five Howth 17s built for 1898 by John Hilditch immediately after he had completed the Belfast Lough Class I boats. Photo: John Deane

This concentration of yacht design development in a short time span, and through just one boatyard, is rare but not unique – the great name of Charlie Sibbick of Cowes shone equally briefly but even more brightly at much the same time, as he was a designer too. But Sibbick made his name in an established international centre for sailing. Yet when John Hilditch – who was both a seafarer and a fully-qualified shipwright – established his yard at Carrickfergus on Belfast Lough in the winter of 1892-93, the north of Ireland was still a relative backwater in international sailing terms. Thus his achievement is indeed remarkable. For by the time Hilditch closed down in the winter of 1913-14, he had put Belfast Lough firmly in the global picture as a pace-setter in yacht development, and his pivotal role in that transformation is gaining increasing recognition.

Not that there hadn’t been sailing in Belfast Lough before Hilditch came along. There are many yacht and sailing clubs around this fine stretch of sailing water, and the most senior of them is Holywood Yacht Club (on the waterfront below the hills where Rory McIlroy learned to pay golf), which dates back to 1862. And in 1866, two more new clubs came into being – Carrickfergus Sailing Club which was obviously location-specific, and the Ulster Yacht Cub, which became the Royal Ulster Yacht Club in 1869, but was a premises-free moveable feast until 1898, when America’s Cup challenger Thomas Lipton insisted it have a clubhouse, which was duly opened on an eminence close above the Bangor waterfront in April 1899.

The shared foundation year which goes back through the mists of time to 1866 means that both clubs will be celebrating their 150th Anniversaries in 2016. They’ve been quietly working on their separate plans towards celebrating this significant date, with a massive new history of the RUYC under way for a couple of years now and due for publication in the Spring, while Carrickfergus also has plans in the publication line.

Yet although there is much to write about now, in both club’s cases the pace of development was relatively slow until the late 1880s, for until that time, the business of the rapidly expanding city of Belfast was business, and more business. It wasn’t until the 1880s that leisure sailing began to get serious attention from the rapidly growing middle classes of the greater Belfast area. But once they did begin to take it up, they did so with complete enthusiasm, and the sailing pace of Belfast Lough during the 1890s, and on towards 1910, had few rivals.

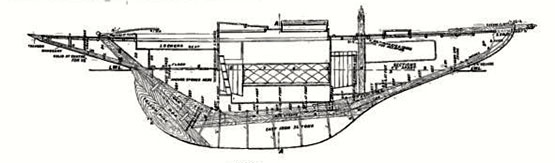

For the rapid yacht design development seen during John Hilditch’s busy years, compare this with the next image. The old-style hull of Peggy Bawn is revealed as she is lifted out of the Coal Harbour Yard in Dun Laoghaire in 1996 for a first attempt at restoration. Later, Hal Sisk took over the project, and it was completed for him by Michael Kennedy of Dunmore East. Photo:W M Nixon

The new style shape. Although they were built only three years after Peggy Bawn, the Fife-designed Belfast Lough Class I boats had a much more modern hull shape and were primarily racing boats, yet they were required to be well capable of sailing to Scotland and Dublin Bay, and did so

The new style shape. Although they were built only three years after Peggy Bawn, the Fife-designed Belfast Lough Class I boats had a much more modern hull shape and were primarily racing boats, yet they were required to be well capable of sailing to Scotland and Dublin Bay, and did so

Formidable performers. The Belfast Lough Class I boats Merle (6, Brice Smyth) and Flamingo (2, John Pirrie) racing hard in 1898. Both owner-skippers were members of Carrickfergus SC, and based their boats there. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

Formidable performers. The Belfast Lough Class I boats Merle (6, Brice Smyth) and Flamingo (2, John Pirrie) racing hard in 1898. Both owner-skippers were members of Carrickfergus SC, and based their boats there. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

In order to meet this demand, John Hilditch was able to expand his new boatyard at an extraordinary pace. Even then, he couldn’t keep up with demand, such that one new Belfast Lough class, the Linton Hope-designed lifting-keel 17ft LWL Jewel Class of 1898, had to be built in Chester in England. And at the same time, the fishing-boat builder James Kelly of Portrush on the North Coast found that yacht-building to supply the new craze was much more lucrative than producing his own variant of the classic Greencastle yawl for fishermen on both the Irish and Scottish coasts, and he went into yacht-building both for Belfast Lough and Dublin Bay.

But in terms of overall contribution to the transformation of Belfast Lough sailing, John Hilditch was very much in a league of his own. So much so, in fact, that noted international classic sailing polymath Iain McAllister got to thinking last winter that even though no trace whatsoever now remains of this once famous yard, it was time and more for John Hilditch’s work to be celebrated, and how better than a Hilditch Regatta during 2016 to tie in with other Belfast Lough sailing celebrations?

It’s a great idea which seemed almost too good to be true. But thanks to quiet work behind the scenes, most notably by Wendy Grant who recently became Commodore of Carrickfergus Sailing Club neatly in time to hold the top post during the 150th celebrations (she’s the mother of renowned offshore navigator Ian Moore), plus a special sub-committee in RUYC which likewise holds to the notion that the early stages of good work are best done by stealth, a programme is emerging which will keep all organising parties happy while providing participants with a manageable user-friendly schedule.

It has all become viable during this past week thanks to the confirmation that the more distantly-located significant classic boats of the Hilditch oeuvre – Peggy Bawn of 1894, Tern of the 1897 Belfast Lough Class I, the Howth 17s of 1898, and Trasnagh, the Island Class yawl of 1913 – all hope to be in Belfast Lough towards the end of June 2016, where numbers will be further swollen by the Hilditch-built Royal North of Ireland YC Fairy Class of 1902, together with some of their sister-ships from Lough Erne.

The Hilditch-built Tern in a breeze of wind on Belfast Lough, 1898

Tern in a breeze of wind at St Tropez, September 2015.

In addition, the fleet will be increased by other classics of every type, coming together to wish the Hilditch boats well at this special time. And there’ll be a goodly contingent of Irish Sea Old Gaffers which will be heading towards the big event on Belfast Lough in late June by way of the Old Gaffers Rally at Portaferry in the entrance to Strangford Lough from June 17th to 19th.

But before getting carried away by anticipation of all this festivity, let us remember that this week’s thoughts were introduced by a precautionary reminder that the boat-building trade is no bed of roses. So just what did go wrong, that the much-admired Hilditch yard faced closure before the end of 1913, with the man himself dead – perhaps broken-hearted – before the end of 1914?

There seem to be a number of explanations, all of which combine to explain the sudden demise of a great enterprise. The incredible rate of economic expansion in Belfast – which had been accelerating virtually every year since around 1850 – seems to have first shown significant signs of slackening in 1910. The greater Belfast economy did continue to expand in the broadest sense, but the rate of expansion was now slowing.

During the rapid growth years, John Hilditch was able to meet demand, but regardless of the underlying economic patterns, by 1910 his market was beginning to reach saturation levels. If people had continued to change their boats every three years or so – as they’d anticipated doing when the Belfast Lough One Design Association was established in 1896 – then an artificial demand might have been maintained. But people were beginning to realise that a good one design boat was good for much longer than a mere three years. In fact, some argued that a class was only bedded in after three years. So the number of new boats being ordered dried to a trickle.

Yet those boats that were being ordered became individually larger. When the Alfred Mylne-designed 39ft Belfast Lough Island Class yawls began to be conceptualised as the world’s first true cruiser-racer one designs in 1910, they would be far and away the biggest and most expensive one designs Hilditch had yet built. He held out for a price of £350 per boat, but the potential owners – hard-headed Belfast businessmen determined to drive a tough bargain and not to be seen to weaken – wouldn’t budge beyond £345.

In those days, yacht-building was simply priced by overall length, so Hilditch resigned himself to accepting the £345 by agreeing to build a boat with a slightly shorter bow. For all parties, it was a case of cutting off one’s nose off to spite one’s face. The new Island Class yawls were handsome enough. But with a longer bow, they’d have been beautiful.

The island Class yawl Trasnagh, seen here in her first season of 1913, is believed to be the last boat to have been built by John Hilditch. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

The island Class yawl Trasnagh, seen here in her first season of 1913, is believed to be the last boat to have been built by John Hilditch. Photo: Courtesy RNIYC

The last of them, Trasnagh herself in 1913, was the last boat to come out of a formerly great yard rapidly tumbling towards extinction. The times were restless politically as well as economically, so it wasn’t a good time to rely on building pleasure boat for a living. And apart from the saturation of the market and the financial demands of building the relatively large Island Class boats, sailing was no longer attracting the same number of newcomers, as rival interests such as motor cars and aeroplanes were taking away many potential enthusiasts,

Yet ironically, had John Hilditch been able to hang on for just another year into the beginning of the Great War of 1914-18, a slew of war work for the Admiralty would have given his yard a new lease of life. But it was not to be. The yard was gone. And soon, so too was the man himself.

But the boats live on. One hundred and two years after John Hilditch’s death, boats that he created are still sailing the seas, and their assembly in Belfast Lough from June 22nd 2016 onwards will be a reminder that, once upon a time, on a site long since covered by Carrickfergus’s re-developed waterfront, John Hilditch and his team built nearly a hundred fine yachts, the best of which have well stood the test of time. All that together with the 150th Anniversaries of two remarkable sailing clubs. For sure, late June on Belfast Lough is going to be one very special time.

Trasnagh restored for her Centenary in 2013