Displaying items by tag: Winkie

Afloat's WM Nixon Will Tell Galway Sailors That Irish Were First To Leave Gaff Rig

Afloat.ie’s W M “Winkie” Nixon will be talking the talk at Galway Bay Sailing Club’s mid-week gathering at 8pm on Wednesday, February 1st in the re-vamped clubhouse at Rinville in Oranmore, and all are welcome.

The hospitable GBSC clubhouse is at the heart of one of the main sailing centres on a coastline as much renowned for its association with gaff-rigged traditional craft as it is for being the base for some of Ireland’s most modern offshore racers. But in a wide-ranging profusely-illustrated talk, one of the points Nixon will be making is that it was leading Irish amateur sailors who were in the forefront of the changeover from gaff to Bermudan rig.

Drawing on his extensive experience of sailing both abroad and in Ireland (which he has cruised or raced round more times than he can remember), as a sailing journalist and historian Nixon has discerned significant sailing trends which first emerged in Ireland, but became obscured by major national historical events.

However, he promises that the main theme of his talk – “When Gaffers Weren’t Old” – is the sheer pleasure and fascination of sailing. Admission is free and open to all, but a seaboot at the door will be there to receive €5 from anyone who feels like contributing to the Lifeboats.

Round Ireland Yacht Race – Where Next? What Next?

#roundireland – The biennial Round Ireland Race from Wicklow is the jewel in Ireland's offshore racing crown. It may only have been established as recently as 1980, but now it is a classic, part of the RORC programme, and an event which is very special for those who take part. In fact, for many Irish sailing folk, having at least one completed Round Ireland Race in your sailing CV is regarded as an essential experience for a well-rounded sailing life. Yet despite fleets pushing towards the 60 mark in the 1990s, even before the economic recession had started tobite the Round Ireland numbers were tailing off notwithstanding the injection of RORC support, and the more recent bonus of it carrying the same points weighting as the Fastnet Race itself. At a time when the basic Fastnet Race entry list of 350 boats is filled within six hours of entries opening for confirmation, and when the Middle Sea Race from Malta has confidently soared through the 120 mark, while the 70th Sydney-Hobart Race in seven weeks time will see at least a hundred entries, the Round Ireland Race fleet for 2014 was only 36 boats, of whom just 33 finished. W M NIXON wonders how, if at all, this situation can be improved.

"The Round Ireland Race is the greatest. Why don't more people know about it? Why aren't there at least a hundred top boats turning up every time it starts? It's a marvellous course. We had great sailing and great sport. Can somebody tell me why a genuine international offshore racing classic like this has been going on for 34 years, and yet in 2014 we see an entry of only three dozen boats?"

The speaker isn't just any ten-cents-for-my-opinion waterfront pundit. On the contrary, it's Scotsman Richard Harris, skipper and part-owner with his brother of the potent 1996 Sydney 36 Tanit, the overall winner of the Round Ireland Race 2014. And he's asking these questions as someone who has raced with success in both the Fastnet and Sydney-Hobart Races, and has campaigned his boat at the sharp end of the fleet with the RORC programme from the Solent, and in any worthwhile offshore racing he has managed to find in his home waters of Scotland.

Harris is getting into fine form, as we're at the Tanit table for Wicklow Sailing's Club's Round Ireland Prize-giving Dinner-Dance in the Grand Hotel in Wicklow town last Saturday night. With a boxload of trophies for Tanit to collect, anyone would be in exuberant spirits. But his views on the quality of the Round Ireland Race are clearly thought out and genuinely held, and he is enthusiastically supported by his navigator, Richie Fearon.

Fearon is the man to whom the Tanit crew give the lion's share of the credit for their success, which was achieved by just six minutes from Liam Shanahan's J/109 Ruth from the National YC in Dun Laoghaire. He was the only one in Tanit's crew who had done the race before, and in an all-Clyde lineup, his was the only Irish voice, as he sails from Lough Swilly YC in Donegal. His previous race was in 2010 with the Northern Ireland-based J/124 Bejaysus (Alan Hannon), which finished 7th overall. But for the Derry man, second time round made the course if anything even more interesting.

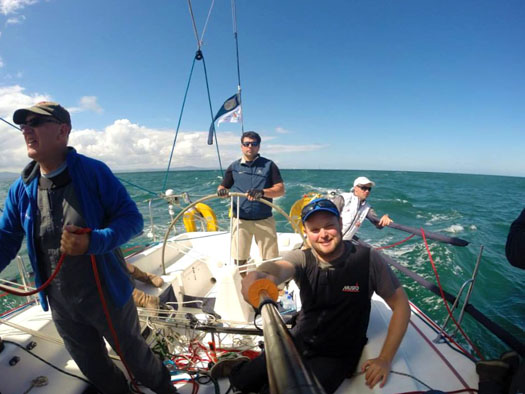

"You get a wonderful sense of the race progressing all the time, of moving along the course" says Fearon. "In the Fastnet, for instance, there are periods when you feel as though you're sailing in a sort of limbo. But in the Round Ireland, you're always shaping your course with the next rock or island or headland or wind change or tidal time in mind. There's a fascinating and challenging mix of strategy and tactics and navigation and pilotage, all of which results in one of the most interesting distance races in the world. They really should get more people to do it. It gives a wonderful feeling of achievement and completeness when you just finish the course. And it's even better if you do well, as we felt we'd done in 2010. But believe me, winning overall, and in a boat as interesting as this with a crew of guys as good and as friendly as this, that's the best of all!"

Richie Fearon of Lough Swilly YC, seen here kitted up off Cape Town for the Transatlantic race to Rio, navigated Tanit to the overall victory in the Round Ireland 2014

So how do you explain to such people, people who have become Round Ireland enthusiasts with all the zeal of recent converts, just why it is that Ireland's premier offshore event can barely attract a viable quorum when the yacht harbours of Europe are bursting with high-powered offshore racing boats which are constantly on the lookout for events worthy of their attention, not to mention commercial offshore racing schools and training programmes which need events like the Round Ireland Race to stay modestly in business?

How indeed, when we already have enough difficulty in explaining it all to ourselves. Inevitably, we have to look at the history, and the setting of that history. The last time I was at the Round Ireland Prize-Giving Dinner-Dance in Wicklow, there'd been enough participants from my home port of Howth in that year's race to make it worthwhile for us to hire a bus to go down through the Garden County for the party. We were in the midst of the Celtic Tiger years when people's expectations were becoming very pretentious, and I remember two foodies seated nearby in the bus pompously hoping to high heaven that the evening's meal wouldn't be the inevitable rural feast of beef or salmon.

But the charm of Wicklow town is that, though it's barely a forty minute drive from the capital, it is very much of the country - l'Irlande profonde as you might say. 'Tis far you are from big city notions of fancy menus to appeal to jaded metropolitan taste-buds. So it was indeed beef or salmon. Not that it really mattered that much to the crowd on the bus from Howth. They were well fuelled with on-board liquor by the time we got there, and the return journey in the small hours was made even longer by the need for frequent comfort stops, thus all they'd needed in the meal was absorbent food to mop up the booze.

Some things have changed greatly in the past few years, not least that there was so little Howth involvement in 2014's race that one very modest car would have done to get all the participants to last Saturday night's prize-giving dinner dance in Wicklow. But some things, thank goodness, don't change. It was still beef or salmon. And very good it was too, as salmon is excellent fish if you don't try to pretend that it's steak and grill it. That brings out its least attractive taste elements. But a baked darne of salmon with a well-judged sauce, such as we had last Saturday night, is a feast for a king. And I gathered the roast beef was very good too.

But it all reinforced the feeling that we were in the biggest hotel – the only hotel? - in a small Irish country town. Yet apart from the sailors at the night's event, there was nothing to suggest that Wicklow is a port, for there's something about the layout of the place which makes the harbour waterfront wellnigh invisible unless you seek it out. It's a delightful surprise when you do find it, but it's very much a little working port, rather than a natural focus for recreational boating and the biennial staging of one of the majorevents in the Irish sailing calendar.

You almost have to take to the air to see that Wicklow is a little port town, for as this photo reveals, the main street turns its back very decisively on the workaday harbour in the Vartry River.

It was back in 1980 that Michael Jones of Wicklow Sailing Club took up boating magazine publisher Norman Barry's challenge for some Irish boat or sailing club, any maritime-minded club at all, to stage a round Ireland race. Jones went for the idea, and Wicklow have been running it every other year ever since. It may be the jewel in Irish offshore sailing's crown. But in Wicklow's little sailing club, it is the entire crown, and just about everything else in the club's jewel and regalia box as well.

Whether or not this is good for the general development of sailing in Wicklow is a moot point, but that's neither here nor there for the moment. What matters is that as far as the growth and development of the Round Ireland Race is concerned, in the early days of the 1980s the fact that Wicklow was a basic little commercial and fishing port with only the most rudimentary berthing facilities for recreational boating didn't really matter all that much, as most other harbours in Ireland were no better.

In 1982, the great Denis Doyle of Cork decided to give the race his full support with his almost-new Frers 51 Moonduster. Denis was someone who strongly supported local rights and legitimate claims, and he reckoned that the fact that Wicklow Sailing Club had filled the Round Ireland Race void, when larger longer-established clubs of national standing had failed to step up to the plate, was something which should be properly respected. So in his many subsequent participations in the Round Ireland Race, Moonduster would arrive into Wicklow several days in advance of the start, she would be given an inner harbour quayside berth of honour in a place as tidy as it could be made in a port which seems to specialise in messy cargoes, and Denis and his wife Mary would take up residence in a nearby B & B and become Honorary Citizens of the town until each race was started and well on its way.

Like father, like son. Denis Doyle's son Frank's A35 Endgame from Crosshaven berthed in Wicklow waiting for the start of the Round Ireland Race 2014, in which she placed fourth overall and was a member of the winning team for the Kinsale YC Trophy. Photo: W M Nixon

It was an attitude which they brought to every venue where Moonduster was raced. The Doyles believed passionately that boosting the local economy should be something that ought to be a priority in any major sailing happening, wherever it might be staged. Denis had been doing the biennial Fastnet regularly for many years before he took up the Round Ireland race as well, and for a longtime beforehand he and Mary had also had the Honorary Citizen status in Cowes, as he would make a job of doing Cowes Week beforehand, living in digs in the town, while at race's end in Plymouth, there'd be a local commitment as well, albeit on a smaller scale.

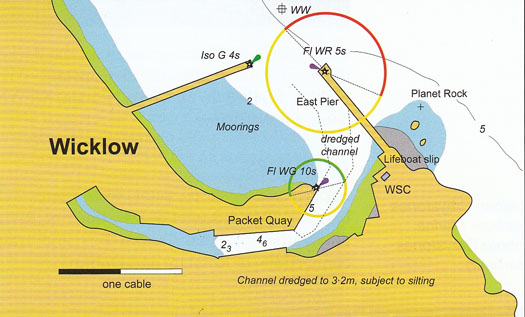

This was all very well for Wicklow and the Round Ireland in the circumstance of the 1980s, but by the 1990s other ports were developing marinas and providing convenient facilities, yet Wicklow stubbornly stayed its own friendly but inconvenient self. When we look at the geography of the harbour, we can see why, and see all sorts of things that might have been done differently a very long time go.

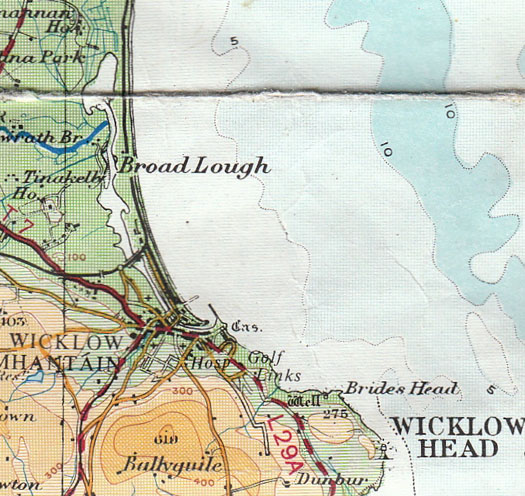

For instance, when the Vikings were first invading and intent on making Wicklow one of their key ports, it could have been developed in a much more useful way if only the native Irish had made them welcome. Can't you just see it? "We'll overlook the rape and pillage for now, lads, these guys represent substantial inward investment". Just so. Had there been that far-sighted attitude, the locals could have invited the men in the longships to come on up the River Vartry, and into the magnificent expanse of the Broad Lough. What a marvellous vision that would have revealed. With some minor rock removal and a little bit of dredging in the entrance, it could be a wonderful extensive natural harbour in a beautiful setting. Had that happened, just think how differently the facilities of modern Wicklow harbour might now be.

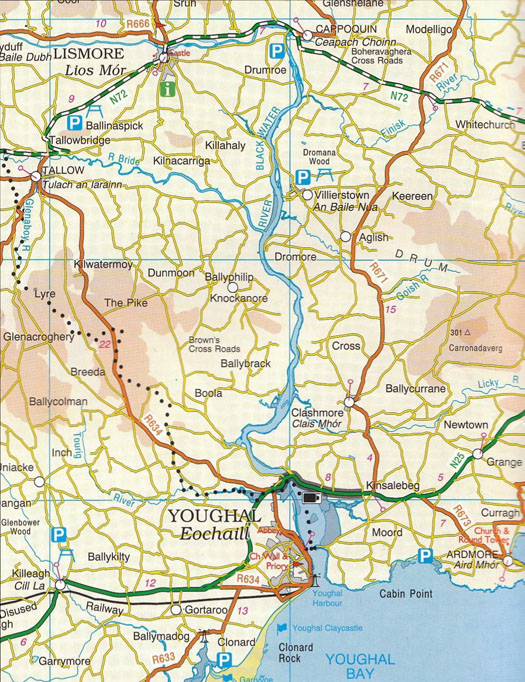

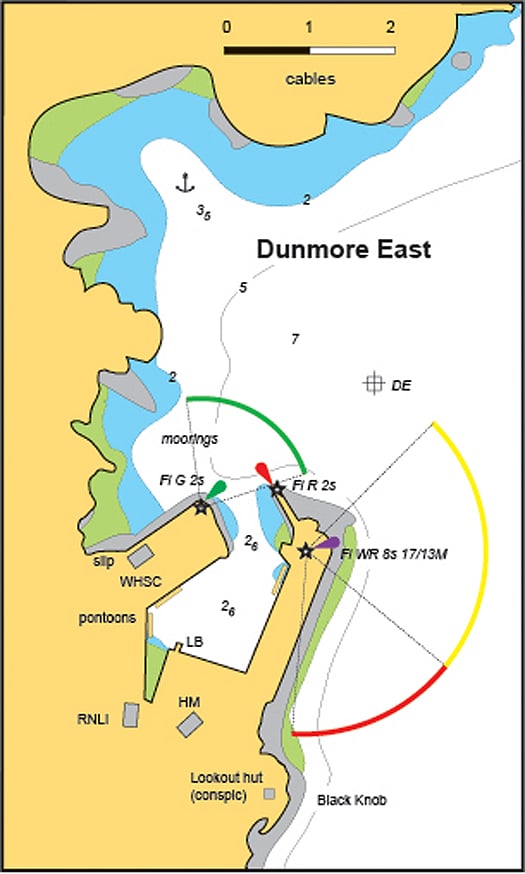

The navigable part of Wicklow Port as it is today. The water does not really come to a sudden straight-line stop as shown on the left – that's just the bridge. Plan courtesy Irish Cruising Club

The bigger picture. Had the Vikings not been stopped such that they had to establish their settlement at the mouth of the Vartry River, they might have been able to create a much larger harbour settlement further in around the shores of the Broad Lough, with obvious advantages for Wicklow Port as it might have become today

Instead, the Vikings struggled ashore on the first available landing place at the first bend of the river, and established a beach-head which became such a successful little fort that eventually they were able to burn their boats. But by thattime, they were totally committed to having Wicklow town in its present cramped location. Access to the Broad Lough at high water (there's a very modest tidal range tidal) was soon restricted by the bridge, and then other river crossings, such that today nobody thinks of it as a potential harbour at all, if they ever did.

But meanwhile the current inner harbour is a cramped and dirty river which seems to be ignored by the town as much as possible, such that even the Bridge Tavern, the birthplace of Wicklow's most famous seafarer, Captain Robert Halpin of SS Great Eastern and trans-oceanic cable laying fame, turns its back firmly on the port. And as for the outer harbour, while it's a delightful place on a summer's day, it is not a serious proposition for berthing a large fleet of boats preparing for a major 704-mile offshore race, but people have to make do with it as best they can.

Despite being the birthplace of the most famous Wicklow seafarer, Captain Robert Halpin, the Bridge Tavern turns its back on the harbour. Photo: W M Nixon

Wicklow's Outer Harbour on the morning of the Round Ireland race 2014 is a lovely sunny spot..............Photo: W M Nixon

....but it is the inner harbour, shared with fishing and other commercial craft and assorted non-maritime quayside businesses, which will shelter the fleet preparing for the Round Ireland Race. Photo: W M Nixon

It was in the 1990s when the Round Ireland fleet was at its peak that the problems with the harbour's limited facilities were at their most acute, and it may be dormant memories of those difficult conditions which contribute to today's shortage of enthusiasm for the race. Back in the 1990s, the average cruiser-racer was not kitted out as a matter of course to RORC requirements, thus those undergoing their first scrutiny in order to be allowed to race round Ireland had to get to Wicklow several days in advance, and then often spendmoney like water to get up to scratch, the necessary bits and pieces being supplied by chandlers' vans parked on the quay.

It was crazy, not unlike a waterfront version of Ballinasloe Horse Fair - all that was missing was Madame Zara in her shiny caravan giving out nautical horoscopes in sepulchral tones for the wannabe Ireland circumnavigators. Perhaps she was there, but the two times I was going through the process with my own boat, it was so hectic I wouldn't have noticed. All I wanted to do was get to sea and away on the race, and get the filth of Wicklow harbour washed off the boat as soon as possible, as we'd drawn the short straw and had been berthed right in against the quay, so everyone has used our boat as a 35ft doormat on their way across to their own craft.

But the finish of the race at Wicklow – now that was and is completely different. The place seems to have transformed itself while you've been away bashing through sundry waters and a lot of the Atlantic in the intervening five days. Everyone is feeling like a million dollars, and Wicklow seems the only proper place in the whole wide world to finish a major offshore race. And as for the Round Ireland Prize Giving Dinner Dance, the venue of the Grand Hotel and beef or salmon for the meal is all part of the formula, it's central to the mystique of this extraordinary event.

In the days of the big entries with massive sponsorship from Cork Dry Gin, the prize-giving was Dublin-centred even if the race had started and finished in Wicklow. And the big bash in the city would start with a huge reception leading on into a gala dinner (I don't remember much dancing) in a glitzy Dublin hotel. In truth, it seemed a bit remote from little boats making their ways alone or in ones and twos back into Wicklow after the profoundly moving experience of racing right round our home island.

By the time you'd done all that, only others who have done the same could truly share your feelings about the experience. Big parties in anonymous city hotels were not the ideal setting for the Autumnal prize-giving and de-briefing. Thus the contemporary final hassle of getting down to Wicklow for the Round Ireland Dinner on a black November night in a veritable deluge of a downpour could be seen as the last stage of a long weeding-out process.

But once you're into the Grand Hotel and the party is under way, it's magic and the camaraderie really is quite something. Old rivalries and grievances fade away. It is also, to a remarkable extent, a family gathering – the number of family crews involved is surely exceptional. And the tone of it for 2014 is set by the presence of the winner of the KYC Trophy for the best three boat team, for the winners had as their top-placed boat the A35 Endgame, fourth overall and owner-skippered by Frank Doyle RCYC, son of Denis and Mary Doyle.

However, inevitably the status of the race and its future development and expansion is something which just won't go away. Any doubts about its importance were soon dispelled by considering the special guests at the dinner, as they included the President of the Irish Sailing Association David Lovegrove, the Vice Commodore of the Royal Ocean Racing Club Michael Boyd of the RIYC, and the Commodore of the Royal Irish Yacht Club, Jim Horan, whose club in 2014 was for the first time in association with Wicklow Sailing Club on the Round Ireland Race. The RIYC acted as hosting club in Dun Laoghaire for visiting boats which didn't want to go on down to Wicklow until shortly before the start, but wished toavail of modern marina facilities and the amenities of a large sailing port in the meantime.

The switched-on crews going to Dun Laoghaire before the start of the Round Ireland Race 2014 knew that the best approach was to make themselves known at the Royal Irish YC and get a berth there, instead of allowing their boats to be banished to the "Siberia" of Dun Laoghaire Marina's remote visitors berths. Photo includes the MG38 McGregor IV from Essex which finished tenth overall (left), and the Oyster 37 Amazing Grace from Kerry, which had been in the frame but was forced to retire with equipment failure. Photo: W M Nixon

It was a partnership with potential, but it will need to be worked on. For although boats from other parts of Ireland knew that on arrival in Dun Laoghaire the secret of being well looked after was to make your number directly with the RIYC, boats from further afield coming into Dublin Bay tended to contact the marina, and thus they were stuck into Dun Laoghaire Marina's absurd visitors' berths, which are right at the very outer end of the pontoons, way out beyond acres of currently empty berths, such that it's said that anyone on them is one whole kilometre's walk from dry land.

Before the Round Ireland Race, the eventual winner Tanit was brought up from the Solent to Dun Laoghaire by a delivery crew who contacted the Marina Office, and she was stuck out in the Siberia of those Visitors Berths. It did mean that when she was first properly seen in Wicklow Harbour on the morning of the race, her impact as clearly an extremely attractive and very sound all round boat was all the greater. But nevertheless, if that is Dun Laoghaire Marina's idea of making visitors welcome, then they need to do something of a reality check, and it was a telling reminder that many Dun Laoghaire and Dublin Bay sailors are so absorbed in their own clearly defined and time-controlled activities afloatthat it leaves them with only limited attention for events outside their own sphere of interest.

As for Dun Laoghaire's general public, is there any interest at all? If the start of the Round Ireland Race was shifted to Dun Laoghaire, as some suggest, do you think the vast majority of the locals would take a blind bit of notice? At least in Wicklow they do make a bit of a fuss on the day of the start, with a community-sponsored fireworks display the night before.

In a final twist, in setting up the new Wicklow-Dun Laoghaire relationship, nobody had thought of the Greystones factor. Most had been unaware that the new Greystones marina is unexpectedly very deep. But such is the case, as I learned on Saturday night from the man from Newstalk. It's one of the reasons it cost the earth to build the little place. But it did mean that, in the buildup to the Round Ireland Race, while two of the deepest boats, the Volvo 70 Monster Project chartered by Wicklow's "Farmer" David Ryan, and the Farr 60 Newstalk, were unwilling to berth in Wicklow itself, they'd only to go a few miles north to find a handy berth in Greystones, where they were still very much in Wicklow county. There, they were the focus of much attention. For as we've discovered at Afloat.ie, if we lead a story #greystones, the level of interest is amazing.

The exceptionally deep water in Greystones Marina provided trouble-free berthing for the Volvo 70 Monster Project and the Farr 60 Newstalk. Photo: W M Nixon

Perhaps after their attendance at the Round Ireland Dinner in Wicklow last Saturdaynight, Tanit's crew now have a better understanding of why the Round Ireland Race is in its present format. And I certainly understand why the level of close personal attention which goes into the race administration by the small team in Wicklow SC running it adds greatly to its appeal for dedicated participants. Before going to Wicklow, I'd been checking with the eternally obliging Sadie Phelan of the race team whether or not Richard Harris would be there, as I had to admit I thought his boat was only gorgeous. "Of course he'll be there" says Sadie, "and I'll put you at his table".

Not only that, but the winner Tanit's table and the runner-up Ruth's table were cheek by jowl, so much so that I was almost sitting at both of them. It would have taken a team of scribes to collate all the information flying back andforth, but everything was of interest.

Just six minutes separated them at the end.....winner Richard Richard Harris of Tanit (left) and runner-up Liam Shanahan of Ruth at the Round Ireland prize-giving in Wicklow last Saturday night. Photo: W M Nixon

Richard (42) and his brother have owned Tanit for about twelve years, but as his brother is into gentler forms of sailing, the offshore campaigns are exclusively Richard's territory. In early sailing in the Clyde, they'd campaigned a Sweden 36 with their late father while Richard's own pet boat was a classic International OD. But as his interest in offshore racing grew, heidentified the Australian Murray Burns Dovell-designed Sydney 36 as ideal for their needs. He found there was only one in Europe, a 1996 one, little-used and in the Solent. They soon owned her, and changed her name to Tanit as the family firm is Clyde Leather, a vibrant firm which is the only suede tannery in Scotland.

Thus as raced in the Round Ireland, Tanit had the logo of Clyde Marine Leather on her topsides - a useful sideline is suede products for marine use, including a very nifty range of attractively-priced DIY kits for encasing your stainless-steel steering wheel in suede. Show me a boat which has a bare steel wheel, and I'll show you a boat which is on auto-pilot for an indecent amount of the time. But if you are doing the suede coat thing on your helm, be sure to cover the spokes as well, it makes all the difference for ultimate driver comfort.

The boat from God knows where....Tanit (left) was an unknown quantity when she made her debut in Wicklow Harbour on the morning of the Round Ireland Race 2014, but father and son crew Derek & Conor Dillon's Dehler 34 Big Deal (right) from Foynes had already taken part in a couple of ISORA races, and went on to win the two-handed division and place 8th overall. Photo: Kevin Tracey

Gradually, they built up Tanit's campaigning in the Clyde, and most of the crew who currently race the boat have been together for seven years. They also chartered a boat to do the Hobart Race of 2008, but as Scottish offshore racing numbers declined, they decided to give it a whirl with the RORC fleets in the English Channel by moving Tanit down there. They found that the programme of concentrated doses of large-fleet intense offshore racing, all taking place at a venue two hours' flight from Glasgow, suited them very well – they could be totally domesticated when at home without the distraction of the boat being just half an hour's drive down the road.

The Sydney 36 of Tanit's type ceased production in 1997, the Sydney 36 you'll tend to come across now on Google is a new 1998 design. So when Tanit's rudder was wrecked after the 2011 Fastnet (a good race for them), it was something of a disaster as a replacement rudder could no longer be supplied off the shelf. It was even more of a disaster for the unfortunate woman who was driving her five-day-old Range Rover around the boatyard in Southampton where Tanit had been hoisted after returning from the Fastnet finish in Plymouth, for not only was her absurdly big shiny new vehicle severely damaged in somehow colliding with the rudder of the Scottish boat, but it turned out that an inevitably custom-built replacement would cost a cool 35K sterling for her insurance company, as that was one very special rudder.

It was a disaster all round, for by the time they'd identified a high tech builder of sufficient repute prepared to build the new rudder, they had missed most of the 2012 season. Then the 2013 Fastnet Race had too much reaching to suit them, as Tanit is at her best upwind and down. So with Richard's brother making louder noises about selling Tanit in order to suit his more sybaritic preferences afloat, the Round Ireland Race 2014 came up on the radar as being an opportunity for what might well be the last hurrah with a much-loved boat.

They needed a navigator, and preferably one with some experience of the Round Ireland course. Fortunately John Highcock of Saturn Sails in Largs, who regularly races with Tanit as one of those ace helmsmen who can seem to smooth the sea, had sailed with Richie Fearon and suggested him with the highest possible recommendation, so the Swilly man was brought on board.

The rest of the crew were complete round Ireland virgins, but they found the race suited their style and level of sailing very well indeed. In any Round Ireland Race, seasoned observers can usually identify beforehand the half dozen or so boats which will be serious contenders for the overall handicap prize, but which one actually wins will depend on the way the chips fall. But Tanit was something of an unknown, a wild card. Yet it wasn't very far into the race before it became clear that this was a good boat on top of her game, if things came right she'd the makings of a winner.

Tanit settling in after the start. The quicker they got south, the sooner they got back into the sunshine........

....and nearing the Tuskar Rock on the Saturday evening, they were back in sunshine, and well in contention on the leaderboard.

Within the limits of having a sensible boat which professionals would describe as a comfortable cruiser-racer, they campaign flat out. All meals are built around expeditionary and military Ration Packs, which can be quite expensive to buy in ordinary circumstances, but if you can show they're going to be used for a worthy objective, it's possible to swing a deal, and as Richard's wife Vicky is a physiotherapist who is involved with military reserves, the value of Tanit's campaigns is accepted in the right places. The result is a nourishing supply of reasonably attractive easy-prepare instant food which, as Richard reports still with some wonderment, makes no mess at all in and around the galley, yet keeps the crew on full power.

By the time they got up off the Donegal coast, Tanit was right in there, battling with the defending champion, the Gouy family's Ker 39 Inis Mor, for the overall handicap lead, while up ahead the two biggies, Teng Tools (Enda O'Coineen and Eamonn Crosbie) and the Volvo 70 Monster Project, with David Ryan of Wicklow, kept finding new calms as they tried to shake off the smaller craft.

It was a slow race, but Richie Fearon managed to place Tanit so that she stayed ahead of a calm up in his home waters, and was keeping station on Inis Mor very handily indeed, while the gap with boats astern widened all the time. Or so it seemed. But then the Round Ireland Race pulled one of its regular tricks, and Liam Shanahan and his team on the J/109 Ruth began to shift before they'd even got past Tory Island, and they appeared to carry a useful breeze and a fairtide the whole way from Donegal into the Irish Sea, or at least that's how it looked to the rest of the fleet.

But in closing in over the final stage from Rockabill to Wicklow, navigator Fearon – who was incubating a nasty virus which required antibiotic treatment for a week after the race - convinced Tanit's skipper that they should stay offshore, while Ruth – which seemed to have the race nicely in the bag – followed the Irish habit of hugging the coast. Inis Mor was already finished on Friday morning, but Tanit knew she was beatable by them, and when they came across the line at 1030, it was to move into the CT lead. And going offshore proved to have been their win move.

Trophies of the chase – crewman Chris Frize (left) and skipper Richard Harris with some of Tanit's prizes in Wicklow last Saturday night. Photo: W M Nixon

Family effort. Father and son team of Derek and Conor Dillon from Listowel in Kerry (they sail from Foynes) won the two-handed division with their Dehler 34 Big Deal, and placed 8th overall. Photo: W M Nixon

It was a time of screaming frustration for Ruth. She'd been crawling along near Bray Head, barely 15 miles from the finish, as long ago as 0700. She rated only 1.016 to the 1.051 of Tanit. A finish in the middle of lunchtime would do fine. It was so near. It was so far. Finally they got to Wicklow, but Tanit had them beaten by six minutes. Then for the Scottish boat there was just the chance that Ian Hickey's very low-rated veteran Granada 38 Cavatina might do it again. But the wind ran out for her too. Meanwhile Frank Doyle's Endgame came in at mid-afternoon to slot into fourth on CT behind Inis Mor, but Cavatina was fifth, all of five hours corrected astern of Tanit. The Scottish boat was now unbeatable leader.

Tanit's crew for this classic sailing of a true offshore classic was Richard Harris, Richie Fearon, John Highcock, Alan Macleod, Chris Frize, Andy Knowles and Ian Walker. They've a lovely boat of which they're justifiably very fond, but reality has intruded, and now she is indeed for sale. The price is 48K sterling which seems to me very reasonable when you remember that she is remarkably comfortable to sail, that sails and gear have been regularly up-dated, and that we know for certain that the rudder alone is worth 35K.......She's conveniently located for an Irish potential owner, as she's currently ashore in Glasgow. Certainly she has a performance weakness, for as Richard admits, she'll easily get up to 7 knots on a reach, but stubbornly stays there and goes no faster, yet if you harden on to the wind, she'll still be doing 7 knots. But if you go downwind, then whoosh – it's a horizon job on most other boats. Be careful what you wish for, though. With a boat like Tanit in an average fleet, there'll be no excuse for not doing well......

The rest of the trophy placings are here, and on Saturday night they were one lovely compact crowd of people. The family emphasis was inescapable, and it was a particular pleasure to meet the Kerry duo, father and son crew Derek and Conor Dillon from Listowel, who sail out of Foynes in their Dehler 34 Big Deal. In 2015, they plan to take on the two-handed division in the Fastnet, so getting 8th overall and winning the two-handed class in the Round Ireland 2014 was part of a very useful campaign trail.

Finally, as to how to keep the Round Ireland race's distinctive Wicklow flavour while allowing the entry numbers enough room to comfortably expand, it's such a tricky question that it will require a radical solution. A very radical solution. The mistakes of the Vikings must be undone. The Vartry entrance must be dredged, The bridges must all be removed. And the Broad Lough must be tastefully developed to give Wicklow the harbour it deserves, and the Wicklow Round Ireland Race the facilities it needs to cater for a fleet of a hundred and more boats. Simple, really.

ROUND IRELAND RACE TROPHY WINNERS 2014

Line Honours: Denis Doyle Cup - Monster Project (David Ryan, WSC)

IRC Class CK: CK Cup – Monster Project

IRC Class Z: Class Z Cup - Newstalk for Adrenalin (Joe McDonald, NYC)

IRC Class 1: Tuskar Cup – Inis Mor (Laurent Gouy, CBC)

IRC Class 2: Fastnet Cup – Tanit (R Harris, SYC)

IRC Class 3: Skelligs Cup – Ruth (L Shanahan, NYC)

IRC Class 4: Tory Island Cup – Cavatina (I Hickey, RCYC)

Class 5 (Cruiser HF) – Cavatina

Class 6 (pre 1987) Michael Jones Trophy – Cavatina

Class 7 (two-handed) Noonan Trophy – Big Deal (D & C Dillon, FYC)

ICRA Trophy (best Irish boat) - Ruth

Ladies Award: Mizen Head Trophy - Pyxis (Kirsteen Donaldson)

ISORA Award – Ruth

Team Award: Kinsale YC Cup – Endgame (F Doyle), Wild Spirit (P Jackson) & Fujitsu (D B Cattle).

IRC Overall: Norman Barry Trophy – Tanit

Round Ireland Overall: Wicklow Cup - Tanit

Monster boat, monster prizes. Line honours and Class C winner David Ryan of Wicklow, who raced the Volvo 70 Monster Project to success, with Roisin Scanlon, also WSC, who crewed on the Monster during the Round Ireland Race Photo: W M Nixon

Is The New Dublin Bay 24 The Best Way Forward For Old Classic Yachts?

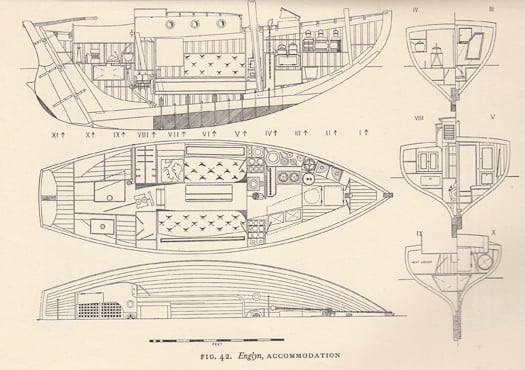

#classicboat – The preservation of old boats can be a contentious issue, particularly so when the vessel is of significant historical interest at several levels, such as Erskine & Molly Childers' ketch Asgard. Technical and academic question arise as to when a refit become a major refurbishment, when does a preservation become a conservation, or when is a restoration veering into being a re-build? Alternatively, should you simply cut your losses and build from new, but using the original plans if the boat meant something very special to you and the larger maritime community? W M Nixon takes a look at three special boats of Irish interest which are currently at an important changes of course in their voyages through life.

Xanadu is no more. Espanola is seeking a new home. And Periwinkle is born again. And no, we're not launching into some imitation of the rolling cadences of Coleridge's Kubla Khan. On the contrary, we're just considering the current circumstances of three very different boats which have the shared factors of being at a significant juncture in their lives, and having strong links with Ireland.

My own first view of Xanadu was coming round the point at Courtmacsherry about a dozen years ago, and being much taken by a couple of big white raked masts vivid against the green West Cork background – clearly, it was an American ketch. Then close up, her handsome dark blue hull, with a delicately understated clipper bow, confirmed her Transatlantic appearance. And the elegant counter, with its raked and almost elliptical transom, reinforced this conclusion.

She was definitely of a type, and yet she seemed different. Something said that this classic yacht was neither a Francis Herreshoff nor a John Alden. Herreshoff was renowned for his large clipper-bowed Bermudan rigged ketches, of which the best known was the legendary Ticonderoga – "Big Ti". And though Alden was most famous for his schooners, he had shown he could turn his hand to classic ketches with raked masts and very positive clipper bows if that was what the client wanted.

But this striking yacht, newly making Courtmacsherry her home port just after the turn of the Millennium, didn't quite fill the Herreshoff-Alden bill. For sure, she had all the typical features. But they were in an elegantly under-stated style which gave her an almost mysterious air, and made you wonder just who might have been the designer, and when.

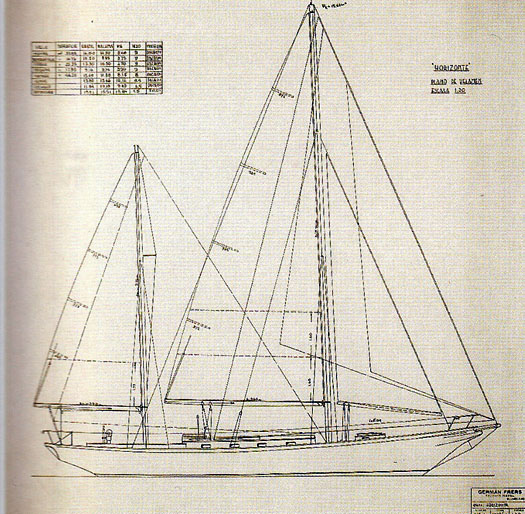

The story was pure gold. The 48ft Xanadu had been designed by the Argentine legend German Frers Senr, patriarch of a yacht design dynasty which is now well into its third generation. The origins of her hull above water was a sweet clipper-bowed ketch called Horizonte which old man Frers had designed for his own use in 1936, but one of his friends and customers liked the boat so much, and was prepared to pay even more to have her, that Frers never became her owner-skipper.

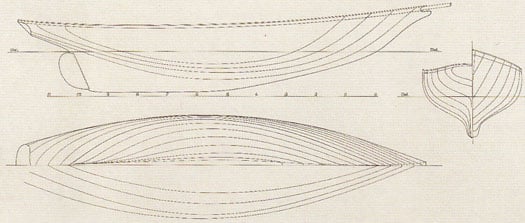

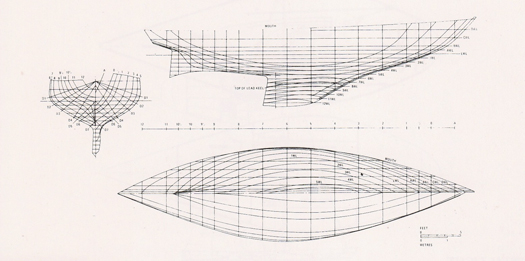

Argentinian designer German Frers designed the 48ft Horizonte for his own use in 1936, but she was snapped up by an enthusiast for his designs, so it wasn't until 1982 that he was able to build the boat as Xanadu for himself (though she too was to be snapped up), and this time she was given a different under-body, with long fin keel and centerboard, and skeg-hung rudder.

The 1936 hull profile for Horizonte.

In fact, it wasn't until 1982, and after owning several other boats of a more ocean-racing orientation to his own design, that Frers Senr had another look at the possibility of Horizonte for his dreamship. In re-sketching her, he retained the handsome above water profile. But as his son German Jnr was now cutting a mighty swathe through the international yacht design scene, with the 1981-built 51ft Moonduster for Denis Doyle of Cork only one of many hyper-successful boats at the front of the fleets, presumably the father took the son's advice on changing Horizonte's underwater profile to a long fin keel with centreboard, and a skeg hung rudder.

Xanadu as she was in June 2014 – the underwater hull profile is very reminiscent of the German Frers Jnr F&C 44 design. Photo: W M Nixon

Certainly the resulting underwater shape is almost exactly the same as the famous Frers performance cruising ketch, the Argentine-built F&C 44, of which Ireland has a fine example in Otto Glaser's Tritsch Tratsch IV at Howth. But the new Xanadu was slightly larger, like Horizonte 16.3 metres (48ft LOA), with a wider stern and more volume in every way – she was big for her size. And once again no sooner was building in progress in steel in Buenos Aires than someone else wanted her, and made an offer that couldn't be refused.

An early owner was a colourful character whose private life was such that the boat, at various stages of completion, seems to have been shifted back and forth across the River Plate between Argentina and Uruguay in order to keep her out of the clutches of a scorned wife who was in pursuit of her share of all the owner-skipper's assets. But eventually Xanadu, as she had evocatively become, found her way into American ownership and embarked on a very civilized 15-year voyage round the world, which she completed with style.

Norman Kean found her for sale in Annapolis. Very much a Scotsman and an enthusiastic member of the Clyde Cruising Club, his work as an industrial chemist had brought him to the DuPont plant in Derry, and for several years he was an active member of Lough Swilly YC at Fahan, starting with a Sadler 25 which he completed himself from a bare hull and deck, with which he undertook round Ireland cruises, the long haul south to Brittany, and a venture north to the Faroes. The latter won him an award from the Clyde Cruising Club, but with his new base he was soon also active in the Irish Cruising Club, and then he up-graded his boat size to a Sigma 33 for six years.

But with the DuPont plant at Maydown facing the closure of most of its operations, he took up an offer of a posting to the main American plant. And when that contract was in turn fulfilled, he took a look at another offer with the company in the late 1990s, but decided that it was time to take the alternative lump sum offer of money, and a new road in life. He and Geraldine had the vision of buying a suitable boat from among the thousands on offer at the US East Coast's three main "boat markets" of Newport RI, Annapolis and Fort Lauderdale, and sailing her back across the Atlantic to run an owner-skippered-charter operation in Southwest Ireland.

Their ideal was a 42-44ft ketch, but then they saw Xanadu in Annapolis, and were smitten. Certainly she was a bit tired, but tired in a well-cared-for way. With a successful charter business keeping them busy each summer, they would have the resources to bring her back to showroom condition over the winter. So they brought her back across the Atlantic, loving their fine big ship even more with every mile sailed, and set about going into business with a base at Courtmacsherry.

And they came up against the brick wall that is Ireland's Department of Transport. After years of struggle and ultimate failure, Norman now looks back on it all with a sort of ironic amusement. "There mustn't be a worse place than Ireland in the whole world to set up an one-boat owner-skippered-charter operation" he wryly observes. "They just don't get it, and they just don't want to get it. Obstructions and objections and prohibitions are put in your way at every turn. They just want you to go away, and leave them in peace to deal only with companies, and the bigger the better".

Certainly the cultural clash between the spirit of the Irish Public Service, in which the ideal is to rise without trace or trouble through the ranks until you reach a level with a highly desirable pension and the possibility of early retirement, is about as different from the Norman Kean approach to life as possible.

But being a man of much energy and vision, he was soon finding other outlets, and became the Honorary Editor of the Irish Cruising Club Sailing Directions, raising them to a new level. He and Geraldine made a formidable research and production team, and for several years, as the new rigorously up-dated editions appeared at remarkable speed, it was the handsome Xanadu which featured as the cruising yacht in the photos in the Directions, showing she had somehow found her way into obscure anchorages, many of them tiny places by comparison with her hefty size.

Xanadu on survey and research service for the ICC Directions at Inishvickillaune in the Blasket Islands. Photo: Geraldine Hennigan

You wouldn't think you could get into a place as small as this, but research is everything....Xanadu in the tiny harbour of Carnlough on the Antrim coast. Photo: Geraldine Hennigan

But without the income of a skippered-charter operation, maintaining a steel ketch of this size and age was becoming impossible. In order not to be impossibly heavy, steel yachts have to be built with only 6mm plate, which is fine for strength but leaves nothing extra to allow for the local corrosion which is almost inevitable and difficult to detect when complex accommodation is fitted into hulls sprayed internally with insulation. Thus even with high level maintenance, it is reasonable to expect that a steel yacht will last only about fifty years without major work being undertaken.

With Xanadu, it was the more visible bits of the ship – the cockpit coamings and cabin sides, for instance, the places in the spray areas - which were most prone to rust. But there were also enough questionable spots, albeit minor, on the hull itself, hidden away by bulkheads, internal furniture and fittings and so forth, which were a cause for real concern. For as long as he could, Norman replaced or repaired the corroding areas, but it was a growing challenge – the ship seemed to be in rapid decline.

The surveying and research for the ICC Directions continued with boats loaned by members – Norman at work in Lough Foyle in 2013 aboard the 35ft Witchcraft provided by Ed Wheeler of Strangford Lough. Photo:W M Nixon

Xanadu was taken temporarily out of commission, but the ICC's research duties continued with boats loaned by members on all coasts of Ireland. Yet every time Norman and Geraldine returned from this absorbing work, they had to face again the problems with their own boat. It was decision time. They had to put Xanadu up for sale, ideally to someone who had the resources to refurbish a still eminently saveable classic. Or else they'd have to watch her rust away before their very eyes.

But the economic recession was in full swing. And selling a boat from remote Oldcourt Boatyard in far West Cork was a very different proposition from frequent showing to the boat-keen crowds who mill about places like Annapolis. The months passed, the years passed, there was interest, but there was nothing which converted into anything realistic. They made the decision that Xanadu was not going to make the 50 years which is the normal life-span of a fully-maintained steel yacht. Instead, she would end her days at the age of 32 while there was still a bit of dignity to it.

It's making the decision which is the really painful part. Once it's made, you're absorbed by the challenges faced in stripping a complex 48ft structure down to a shell, and selling the bits and pieces for sometimes surprisingly good prices, while keeping some special parts for possible incorporation in a new boat.

The last days of Xanadu. Seen here in June 2014, she'll be completely gone within a fortnight from today. Photo: W M Nixon

But as of this weekend, Xanadu is a bare shell, though still at home in the easygoing world of a friendly local boatyard. However, within a fortnight, this empty shell will be moved to the very different world of a scrapyard, and the final coup de grace will be delivered in a matter of hours.

In our modern world, in which such harsh events are kept hidden by professionals from sensitive eyes, we now and again need to reflect on the final reality. But despite Xanadu's fate, there are still many people who continue to preserve old boats for whatever reasons, and by very different means. So we'll round out this piece with the two very different stories of two historic boats which had very special links with Dun Laoghaire and Dublin Bay.

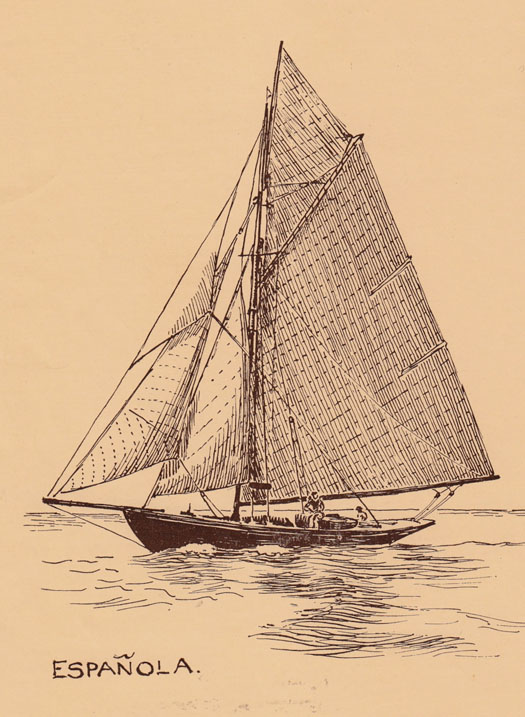

Espanola has sailed through this blog before. A 47ft cutter designed and built by Sam Bond at Birkenhead on the Mersey in 1902, she was originally called Irene VII, but in 1912 she was bought by Herbert Wright of the Royal Irish YC on Dublin Bay who'd been a founder owner in the Dublin Bay 21 class the year Irene was built. He actually cruised his DB 21 Estelle, which must have been an austere business, but certainly Irene seemed luxurious by comparison. And when the King of Spain visited the RIYC clubhouse during a formal visit to Ireland in 1912, as Irene on her moorings was the nearest boat to the clubhouse of any comfortable size, he was taken aboard her to see an Irish yacht, as he was himself a keen sailing man. Almost immediately, Herbert Wright - a fast-thinking stockbroker - re-named his new boat Espanola, and she has been Espanola ever since.

Espanola as she was in 1929. (from a drawing by Billy McBride)

In Herbert Wright's ownership, she made some notable cruises, indeed he was so highly regarded in the Irish cruising community that when the Irish Cruising Club was formed with a cruise-in-company of just five yachts to Glengarriff in 1929, Espanola was one of them, and she came back to Dun Laoghaire as the new ICC Commodore's yacht. It was a role she continued to fill for a dozen years, so it would be quite something of she was still around for the ICC's Centenary in 2029.

Since leaving Ireland in the 1940s, she has had a varied life, but for many years now, she has been owned by Martin Birch, a lecturer at Lancaster University. This means his home port is Preston on the Lancashire coast with, its huge tides and shallow channels. Espanola is very deep draft, so if you set out to choose an unsuitable home port for her, Preston would come well up the list, except that the folk in Preston Marina have adopted her as their sort of pet classic yacht, so Martin has had every assistance possible to keep his big boat in pristine condition.

Espanola as she is rigged today, with a more manageable gaff ketch configuration.

Espanola is currently afloat under these high quality covers in Preston in Lancashire. Photo: Martin Birch

That said, when planks needed replaced she had to be taken to the Menai Straits and one of the boatyards there which are carving out a formidable reputation for quality work on classic and traditional craft. Getting Espanola to the Straits was no bother, as Martin has made some fine cruises with her, notably to the Outer Hebrides. So Espanola is in good shape for a boat of her age.

But after 25 years of total dedication in looking after this big vessel in challenging circumstances, Martin has decided it's time for a change, and Espanola is for sale. However, for someone looking for a flawless classic yacht pedigree, while her hull is totally authentic, Espanola's rig has now been changed from a big gaff cutter to an easily handled ketch, though still gaff rigged, while her accommodation has been made much more comfortable and roomy by the addition of an elegant full-length coachroof.

So today's Espanola is not totally as she was in 1902, but her full history has been traced by Martin Birch, and he has written a privately-published book about it which very effectively reveals why this is an important boat, though a challenge for any owner. However, if you're interested I'll put you in touch with him, but this isn't one for the faint-hearted.

But then, keeping any classic or historic vessel in seagoing shape is never something for the faint-hearted, so we'll conclude with a totally different approach to the methods adopted in the case of Xanadu and Espanola. It must be nearly ten years now since the six surviving Alfred Mylne-designed Dublin Bay 24s were spirited away to Brittany for a planned complete re-furbishment and their intended re-emergence as classic playthings for the mega-rich at a new resort centre to be built in the south of France.

The re-born class was to be known as the Royal Alfred 38s, as 24ft is only their waterline length, and people go by LOA these days. As to the Royal Alfred, it supposedly sounds more posh than Dublin Bay, and it was at a committee meeting of the Royal Alfred Yacht Club in Dublin in 1934 that Gordon Campbell, the second Lord Glenavy and owner of the Dublin Bay 21 Garavogue, first outlined the concept – and a very advanced concept it was too – for a larger more modern Bermudan-rigged one design for racing in Dublin Bay, and capable of some modest cruising.

By 1938, Dublin Bay Sailing Club took over the project, and a design was commissioned from Alfred Mylne in Glasgow. But though building work started in Scotland in 1939, World War II delayed everything, and the class didn't have their first race at Dun Laoghaire until 1947. They were an immediate success - they filled Gordon Campbell's brief to perfection, and for more than five decades they'd great racing in Dublin Bay, they also logged some truly remarkable cruises, and for good measure they did the business racing offshore, with one of them the overall winner of the RORC Irish Sea Race in 1963.

But the setup in Dun Laoghaire does not favour the continued existence of a class of 38ft classic wooden yachts, so the DB 24s had definitely run out of steam when they were swept up by the Royal Alfred 38 consortium. Then the recession arrived, and all sorts of rumours circulated about the boats being held as security against debts, of them being piled away any old how in a warehouse near Benodet in Brittany, and of lots of other things, none of them good news.

That is, until somewhere over a month ago, when I heard from an acquaintance with a Classic in the Balearics that he'd heard a rumour a restored Dublin Bay 24 had been seen sailing in the inner reaches of the Bay of Biscay, and seemed to be very much at home there. This I thought rather good news, as it seems to me to be a much more appropriate setting for these very special boats than the French Rivera with its harsh sun, where the classic yachts are so large that the Dublin Bay 24s, or whatever they were to be called, would be virtually invisible.

The new Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle sailing off La Turballe, August 2014

For once, it's good news, albeit with a slightly sad tinge. The slightly sad note is that the Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle, which never left her birthplace in Scotland and was only united permanently with her sisters when they were all shipped to Brittany several years ago, is now absolutely no more. Well, her tiller still exists and is in use, but whether that's the original tiller from 1948 is another matter. And her lead ballast keel still exists. But the rest of Perwinkle is totally gone, burnt to ashes. Yet Periwinkle still sails, and is looking very well indeed.......

Last glimpse of the 1948 Periwinkle, September 2012

It's quite some story. In 2012, the original Perwinkle was bought by the Francois Vivier organization in France, which specializes in classic boat-building to the highest professional standards, and also creating designs – some of them distinctly quirky, and some which can be built by amateurs. The ideals behind it all have taken off in such a big way in France and abroad that there's an almost religious fervor to some of Vivier's adherents, and the story of Periwinkle will in no way diminish this.

For they took the original Periwinkle, and with a team of qualified shipwrights and trainees, they meticulously took her apart bit by bit in order to see how she had been built, and to give them the information to build an exact replica, albeit in different wood technologies such as the use of laminated frames.

Perwinkle built anew – the laminated frames go into place

Looked at a certain way, it's all a bit morbid – we're in the surgeon's dissecting theatre here. And no, I don't know if they had an audience, but it's for sure they would have had no troubling assembling one. Then, with all the information to hand, and with every last little dismantled bit and piece for further confirmation, Francois Vivier drew out new plans for the re-construction. Periwinkle re-born took to the water in August this year, and she looks only gorgeous.

The new Periwinkle on her launching day – she'll be known as a Dublin Bay 24

With her teak decks looking immaculate, the new Perwinkle goes afloat for the first time.

You'll be glad to hear she's known as a Dublin Bay 24. And such is Francois Vivier's following, I wouldn't be at all surprised to hear of a new class in the making on France's Biscay coast. For with Gordon Campbell's vision, the further experienced input of the committees of both the Royal Alfred Yacht Club and Dublin Bay Sailing Club, and Alfred Mylne's genius, they got one marvellous yacht.

So there it is. The three choices with an important but ageing classic yacht. Euthanasia. Or the continued dogged preservation against all the odds. Or a complete re-build. Not easy, any of them.

No, you're not seeing things, this is undoubtedly a very new Dublin Bay 24. But it would be impossible to quantify how much she cost, as the entire dismantling and building project has been part of a larger training progamme.

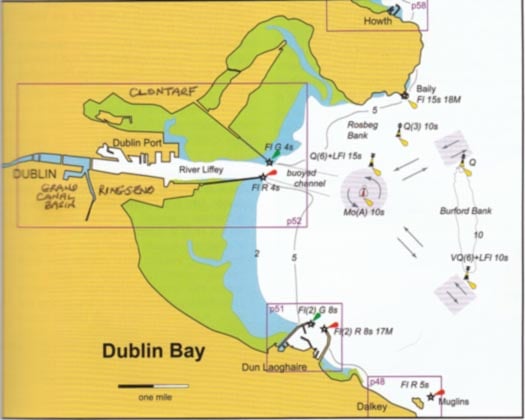

Who Runs Dublin Bay, The Capital's Waterborne Playground?

#dublinbay – Who runs Dubli Bay? Dublin is gradually getting to grips with the sea. Ireland's relentlessly growing and developing capital city is learning that interactive living with the sea and the city's River Liffey, for trade and recreation alike, should be a natural priority for a major coastal conurbation of this status and potential. Thus, formerly derelict industrial waterfront and dockland sites are being re-configured for recreational and hospitality use. And Dublin's ancient maritime communities are learning more of their maritime heritage, and how it can be better understood, both to make these areas more attractive to live in, and to attract visitors. W M Nixon highlights some recent events which show the way forward, but begins by wondering just who's in charge?

It's a good question. For starters, what is Dublin Bay? To keep things as simple as possible, let's agree that Dublin Bay is the area westward of a line between The Baily headland to the north and the Muglins to the south, enclosed then by a dogleg south of Dalkey Island across to the mainland's Sorrento Point at the lower end of Dalkey Sound.

As to how far westward you can reasonably include waterways in the navigable bay area, for simplicity we'll discount the two canals – the Royal and the Grand – radiating from the docks, except for their dockland basins. And as for the River Liffey itself, at high water it may be navigable as far as the weir at Islandbridge, but for most craft, height restriction means that you can go no further than the Matt Talbot Bridge, and even then you're relying on the opening of the Eastlink and Sam Beckett bridges.

So in all we're looking at an area about six nautical miles north to south at the most, and seven miles east to west. But as the east-west dimension is only three miles of open water at low tide, we're looking at a very busy little bit of sea, where multiple uses can often result in potentially conflicting interests trying to share space with each other, while demands on the relatively small sections of accessible waterfront can become acute.

Time was when there was a clear pecking order among the port and bay users, based on commercial demands and the social status of the different activities. Within Dublin port, the Port & Docks Board was effectively its own empire. It had to function effectively, wash its face in financial terms, and get on with the job - and that was it.

While some individual members of the Board may have been concerned with its public image, as perhaps were some of the employees, for the most part it was in the business of making money out of handling ships and their cargoes, and the bigger the better, and that was it – they definitely weren't into public entertainment or the accommodation of the needs of smaller craft. Thus in Dublin as at other ports throughout much of the world, small boat ventures and fishing in particular got little attention – fishing boats and their crews had to make do as best they could with often woefully inadequate facilities.

But as recreational boating developed, new factors came into play. Money talked, and it could be the case that the new breed of recreational sailors were themselves board members or senior professional employees of the Docks Board. And as the new asylum harbour at Dun Laoghaire had developed from 1817 onwards, recreational sailors had the social and economic clout to secure themselves key sites for their private club facilities at this attractive new location.

But that was then. Nowadays, the old system of each interest looking only to its own concerns, and everyone minding their own business if at all possible, just doesn't work any more. The city is bursting at the seams with a new vitality seeking fresh recreational expression, and access to Dublin's maritime heritage. Public and semi-state bodies such as Dublin Port are expected to be much more aware of their image, not only for the general good, but because it has been shown that people much prefer to be working for an organization which is well thought of in the larger community. This means that even the most commercially-minded members of the Port board accept that in the long run it makes economic sense to hold open days, Riverfests, "fun for all the family" happenings, and so forth.

But as this outgoing approach develops, somebody has to be running the show. So who's in charge of the greater bay area? At national governmental level, at the very least the requirements of the Marine Section of the Department of Agriculture and whatever are relevant. So are those of the Departments of Transport, Tourism, and the Environment.

Then there's Local Government. The north side of the bay comes under the Independent Republic of Fingal, which also touches the western navigation limits of the Liffey, as Fingal somehow incorporates the Phoenix Park. Then Dublin City takes over in the inner bay, but South Dublin may think it has some sort of say-so on the innermost bits of the Liffey to the southwest. Southeast of Dublin port, and you're very quickly on the Golden Road to Samarkand, in other words you're into Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown.

A busy little bit of water. Everyone wants a piece of the action on Dublin Bay. Plan courtesy Irish Cruising Club

You'd think that's all enough to be going along with, but bear with me. As far as administration of the built waterfront environment administration is concerned, we're only starting. King of the scene has to be Dublin Port, which really is the big beast in the administration arena. But snapping around its heels on both sides of the Liffey is Waterways Ireland, which has its canals north and south of the River. While WI may have allowed a reduction of the Spencer Dock going into the Royal Canal, across the river the sea-lock-accessed Grand Canal Basin on the south side has the potential to be the jewel in the Waterways Ireland crown, as it has a location to die for and the kind of industries which local authorities dream of – if California has its Silicon Valley, Grand Canal basin is Dublin's Silicon Harbour.

Despite the all-Ireland spread of its remit, Waterways Ireland is a smaller creature than Dublin Port, but you get an increasing sense of boundaries being claimed and defined as this once forgotten area of Dublin docklands comes rapidly alive. And of course another player in our list of statutory authorities which are very interested in the administration of the Dublin Bay area is the Docklands Development Authority, or whatever it's called now in the hope that we'll forget the debacle over the Irish Glass Bottle site.

So our chums in NAMA also have a decision-making role. And then, back in the water, the fact that the Liffey is a living river means that Inland Fisheries is another body than can be rightfully involved, as can organisations concerned with the well-being of those two important tributary rivers, the Dodder to the south and the Tolka to the north.

Sometimes it can seem too crowded for comfort. Ships and smaller craft share a narrow bit of water at Poolbeg. Photo: W M Nixon

All this complexity of administration in the Dublin Bay waterfront may seem convoluted enough already, but we haven't even got to Dun Laoghaire yet. There, the local council have put up the gross new library building as though to offend the other buildings on the established waterfront just as much as possible, while the Harbour Company is actively seeking ways of increasing its income – largely through accommodating cruise liners – as Dublin Port has been hoovering up the cross-channel car, passenger and ro-ro traffic through economies of scale.

Doubtless there are other statutory bodies which may be able to declare a legitimate interest in the running of Dublin Bay, but that's enough for now, so let's look instead at the consumer organisations. At a rough count, I can come up with twelve yacht, boat and sailing clubs, eight of which have premises. There are also at least six coastal rowing clubs, and five sea angling clubs. And there are several national boating bodies, all of which inevitably see a numbers concentration of their membership in the Dublin area, even if they conscientiously ensure that their administration reflects their nationwide nature.

If we really wanted to spread the net, we could come up with significant organization numbers for kite-surfers, windsurfers, canoeists and kayaks too. Plus there are two excellent links golf courses with their clubhouses right in the bay, on Bull Island. And finally, let's not forget Dublin Bay's own very special landmarks, the unused Smokestacks of Poolbeg. Boat users definitely want to keep them – at the very least, they tell us where we are. So we now have the ESB – or is it Electric Ireland these days? – central to a decision which is of great interest to Dublin Bay users.

By all means, let us know at Afloat.ie if you think there's a real need for some overall authority for the bay which can maintain the balance between sea and land, and between work, trade and recreation. It might seem like a good idea. But do we really need yet another level of bureaucracy? Yet another group of Jacks-in-Office who may even have staff with peaked caps and regulatory authorities which enable them to interfere with our natural freedoms?

It's a moot point, but I'll conclude with some experiences of how Dublin Bay is coming along as a genuine amenity for all, and look at some areas of developing interest. Of course, not everything in the garden is lovely. A public event which may have been a good idea on its first staging can become a bit jaded in its second year round, and this seemed to be the case with Dublin Port's Liffey Riverfest.

Last year, it had the attraction of novelty, and it included some Tall Ships, and also the major visit of the Old Gaffers Association international fleet in their Golden Jubilee Year. There was a busy shoreside carnival and many waterborne events including the Ballet of the Tugs and a race series for the historic Howth Seventeens. The restaurant Ship, the MV Cill Airne, provided an excellent administrative and hospitality centre, while downriver Poolbeg Yacht Boat Club's marina provided a very effective main base. It was all great fun.

The "Restaurant Boat" MV Cill Airne has proven very popular with visiting sailors in Dublin Port, but they'd like it even more if they could berth right at the ship. Photo: W M Nixon

So this year they extended the Riverfest to maybe five days in all, and for many who had been there in 2013, it seemed a bit jaded. They'd stepped up the shoreside entertainments, and noisy "fun for all the family" meant less fun for those afloat. The Howth 17s had dutifully turned up to put on a demonstration race or two, but this time round it seemed to be seen as no more than handy background moving maritime wallpaper. And as for the waterborne Ballet of the Tugs (now a daily occurrence throughout the Riverfest), those of our crew who had been there in 2013 said it wasn't nearly as good as last year, but one who hadn't been there in 2013 couldn't believe this - he thought it was absolutely marvelous seeing it for the first time.

The Waterborne Ballet of the Dublin tugs Shackleton and Beaufort impresses those who haven't seen it before, but old Riverfest hands are always looking for something new. Photo: W M Nixon

The Howth Seventeens do their duty with racing in the Liffey in the Riverfest, but for a fickle crowd on the quays always seeking fresh entertainment, the classic old boats are really just a form of moving wallpaper. Photo: W M Nixon

The Seventeens doing what they do best – getting in a bit of real racing. This is the leading group headed for the Clontarf At Home in July, and then on to Ringsend for Echo's Centenary Party at her birthplace. Although Echo (number 8) was the birthday girl, Deilginis (No 11) won the race to Clontarf.

Nevertheless, the old Howth Seventeens had done their duty by the Riverfest at the beginning of June knowing that later in the season, they'd have a weekend completely tailored to their own needs. The Lynch family's Howth Seventeen Echo was built in Ringsend in 1914, the only boat of the class to be built in that ancient maritime community of boatbuilders and sailmakers. So in July the class had their traditional race round the Baily to the Clontarf Yacht Boat Club At Home - an event which is totally tide dependent – then as the tide started to recede, the Seventeens got themselves round to hospitable Poolbeg.

There they were given a snug berth within the marina (most welcome as a giant cruise liner came up the river), then after a Centenary Party in PY & BC which is as near as boats can now get to Echo's birthplace in Ringsend, the party went up the quays to the Cill Airne for a dinner hosted by the Lynches, then after over-nighting at Poolbeg, on the Sunday they sailed home – mostly crewed by families – with a fair wind for Howth to round out a perfect couple of days.

The Howth Seventeens were very glad they'd been put in an inside berth at Poolbeg Marina in July after coming round from Clontarf, as the 113,000 ton cruise liner Ruby Princess was next up the river. Photo: Cillian Macken

The Ruby Princess goes astern into her berth in Alexandra Basin with her bow only yards from boats in Poolbeg Marina. Photo: Cillian Macken

In other words, it was exactly the kind of weekend that most classic local one designs will enjoy hugely, but as entertainment for non-participants and spectators, it wouldn't have registered at all. This is the quandary which harbour authorities have to cope with in trying to give themselves a human face. You're either into boats and other waterborne vehicles, in which case almost anything to do with them is wonderfully entertaining. Or else you're not, in which case total incomprehension, and the ready seeking of almost any other kind of entertainment – and the noisier the better - is almost inevitable when you try to get general public interest and involvement.

Obviously the visit of a significant Tall Ships fleet is something whereby a port authority can combine both genuine maritime interest and public entertainment, but securing one is a major challenge. However, in Dublin port the new user-friendly attitudes have seen the extension of the pontoon beside the Point Depot just above the Eastlink Bridge, and while the rally of the Cruising Association of Ireland was a matter of the crews of around forty boats getting together and enjoying themselves rather than some high profile public entertainment happening, it certainly provided a useful insight into what boat visitors expect in a port.

The Cruising Association of Ireland fleet was a fine sight at the new pontoon.......Photo: W M Nixon

....but because of the need to keep the fairway through the Eastlink Bridge clear, they could only raft three deep. The blue boat in the foreground is Wally McGuirk's own-built 40ft steel Swallow, the last design by O'Brien Kennedy. Photo: W M Nixon

So I might as well start with the bad news. A forthright opinion came from the most experienced cruising man present. In a notably experienced group which included Wally McGuirk's very special own-built steel 40-footer, Swallow, the last boat to be designed by O'Brien Kennedy, being the most experienced is quite something. But whatever it means, it doesn't necessarily include diplomacy. When I asked this most experienced of all the cruising folk present what he thought of the new pontoons, he briskly replied: "They've put them in a stupid place. They should be up beside the Cill Airne, which is where everyone wants to be, and not down here beside the Eastlink Bridge with the likelihood of noisy crowds coming out of the Point Depot at a late hour, and the traffic on the bridge, which also means that we can only raft three deep in order to keep the channel under the bridge clear".

In fact, the CAI's end-of-season rally had a problem of success. Forty boats turned up to provide an impressive fleet but the most they could have at the pontoon, even with rafting, was thirty, so ten had to return through the bridge to Poolbeg where they'd been hospitably received the night before.

Once again, choosing the Cill Airne as the venue for the night's entertainment and meal proved a success, so ideally what's needed is berthing pontoons surrounding the ship herself. It would be mighty convenient, and also solve the inevitable security problems inherent in berthing in a city. But quite what shore-based hospitality establishments in the area would make of a ship in the river receiving such preferential treatment in the guiding of everyone's potential customers is another matter.

While the sea lock into the Grand Canal Basinon the south side of the Liffey went unoccupied the CAI fleet milled about to find berths on the North Quays. Photo: W M Nixon

However, across the river through a sea lock into the Grand Canal Basin, and you're into a snug and secure place that is surely a popular cruising destination that's just waiting to happen. Admittedly in Ireland people seem to have an aversion against having to transit a lock to enter port, but as they'll already have had to come through the Eastlink, having the lock ready can be part of the package. Within, you're totally secure, safe from big ships in the river and within easy reach of many facilities, including even the Daniel Liebeskind-designed Grand Canal Theatre.

The total shelter of the Grand Canal Basin beside the Liebeskind-designed theatre. Photo: W M Nixon

Even with other users such as trainee windsurfers and the Viking Splash ambhibian using the rad Canal Basin, there is still plenty of room for visitors. Photo: W M Nixon

Now that it has been sold to people of taste and discrimination, presumably we can hope that its clumsy current name of the Bord Gais Energy Theatre can be changed pronto. Admittedly there used to be a beloved little venue in Dun Laoghaire in the 1950s and '60s which was the Gas Company Theatre, and many a sailing person enjoyed an entertaining night of drama there. But times have moved on, and even public utilities have to be given more interesting and original names. Certainly when you have a situation where people unfamiliar with the First Official Language think that Ireland's newest and most glamorous place is known as the Bored Gosh! Energy Theatre, then something drastic yet creative has to be done.

Being in and around the Grand Canal Basin – which dates back to 1796 – really does give a sense of the past, even if many of the buildings are very new. But just across the River Dodder is Ringsend, and that is a place which is re-discovering its history as one of Ireland's most interesting maritime communities.

The view northward down the River Dodder from Ringsend Bridge towards the Point Depot on the other side of the Liffey. The entire riverbank on the right used to be a mix of boatyards and other marine businesses, but all that was swept away when the Thorncastle Street Dublin Corporation flats were built in 1954. Photo: W M Nixon

A packed house in Poolbeg Y & BC on Thursday night heard Cormac Lowth talk on the distinctive Ringsend sailing trawlers, and how they traced their development directly back to the arrival of Brixham trawlers from Devon, which were able to begin fishing the Irish Sea in 1818 a couple of years after the end of the Napoleonic Wars.

Brixham was a hive of fishing development and expansion at the time, and their fleets ranged the seas between Dublin Bay to the northwest and Ramsgate in Kent to the east. They originally were enticed to the facilities at the little Pigeon House harbour down along the South Wall, but soon crews were settling, such that nowadays in Ringsend there are still several prominent surnames which can be traced directly back to Devon.

With the Irish community established, there was much intermarriage, and the locals soon acquired the imported skills. Ringsend in those days was almost an island, and with its characterful fishing community, it attracted artists such as Matthew Kendrick and Alexander Wiliams, both of whom lived in Thorncastle Street, the main thoroughfare where the houses backed onto the River Dodder, along whose banks marine industries prospered.

Ship-building flourished, and one of the most talented families in this craft was the Murphy clan, who built on the banks of the Dodder (and then themselves fished) one of the mightiest cutters of them all, the 70ft St Patrick. But the demands of sailing such a boat with the standard crew of just three men and a boy were such that subsequent boats of both Brixham and Ringsend were ketch-rigged, and it's the ketch-rigged 70-footers such as Provident which we know as the classic Brixham trawler today.

Provident, built in 1924, was one of the last and one of the best of the famous Brixham sailing trawlers.

The 28ft Dolphin, built in 1924 in Ringsend, was a final acknowledgement of the hundred year old link to Brixham. She is seen here on Strangford Lough in the 1960s in Davy Steadman's ownership. Photo: Ann Clementston

Provident was built in Devon in 1924, by which time steam was already displacing sail as the preferred power system for trawlers. The effects of World War I from 1914-18 and the War of Independence in 1921 had further reduced the already much-weakened direct links between Brixham and Ringsend, but in 1924 the young designer-boatbuilder John B Kearney built Dolphin, a 28ft clinker-built gaff ketch, in Ringsend. Her design was a final salute to the Brixham connection, for in shape she was completely different from all Kearney's other yacht designs.