Displaying items by tag: Erskine Childers

Global Circumnavigator Pat Murphy Posts Himself An Erskine Childers Centenary Stamp

Time was when the launch of commemorative stamps by An Post was done with considerable fanfare. But these days it seems that they believe good work is best done by stealth, as the launching last week of stamps to mark the Centenary of the death of Erskine Childers was slipped so far under the radar as to be almost invisible.

But global circumnavigator and former GP14 world standard sailor Pat Murphy (79), who continues to cruise each summer while spending his time ashore between County Roscommon and Dublin, is as sharp as ever. He noted the new issue was coming down the line, and on the very day, November 24th, he took himself to the local post office and posted several featuring Asgard and Childers, including one to himself just to be sure to be sure. It's the first time he has ever done such a thing, he says, but as a lifelong Erskine Childers enthusiast, he reckons it couldn't have been in a more appropriate cause.

Pat Murphy's 40ft world-girdling Aldebaran berthed in Dubin Port. Photo: W M Nixon

Pat Murphy's 40ft world-girdling Aldebaran berthed in Dubin Port. Photo: W M Nixon

Centenary of Erskine Childers’ Execution In Dublin On Thursday, November 24th Will Evoke A Complexity Of Responses

The gaunt but serene Erskine Childers (52) died an hour after dawn on November 24th 1922 in Beggars Bush Barracks in Dublin. He had been captured as an armed opponent of the new Irish Free State Government’s policy of implementing the compromising Anglo-Irish Treaty, resulting in the Civil War which the authorities were now ruthlessly - through a brutal programme of high-profile executions of anti-treaty forces of all ranks – bringing to a speedy if blood-laden end.

Childers died as he had lived, with dignity. Before the execution, he shook hands with each member of the firing squad. And after he had been secured in place and his eyes blindfolded, his last words were: “Take a step forward, lads – it will be easier that way”. Moreover, in the week before his execution, he had his son Erskine Hamilton Childers, a future President of Ireland, come from school to visit him in prison to extract the promise that, in adulthood, he would seek out each surviving member of the Firing Squad to shake his hand.

And further still, he requested that the younger Childers would then find each member of the Government who had signed his death warrant in a similar gesture of reconciliation to close the era of bloodshed which Childers - as someone who had an all-or-nothing approach to life - realised was inescapable before Ireland began to find a way forward, whatever it might be.

Erskine Childers in 1922

Erskine Childers in 1922

MOVING ON AS QUICKLY AS POSSIBLE

So compactly vicious had the War of Independence and the subsequent Civil War become that the death of Childers would have been noted in Ireland as inevitable, as something to be moved on from just as quickly as possible. And in the broader world in which he had once held the position of one of the English language’s most popular authors of unusually-themed spy thrillers, the change in his status at the time of his death was so total that people either blanked out his memory in confusion, or else preferred to remember only the star-spangled period of his life, with his final decade being consigned to oblivion as a total aberration.

And now, 152 years after his birth, everyone considers Childers through the lens of their own particular interests. Political and military historians assess his role in Ireland in the turbulent years from 1914 to 1922 as it affected the development of events. Meanwhile, attitude analysts make much of the total change in his approach from a staunch and enthusiastic unionist and British Imperialist in his youth and early manhood, into an anti-imperialist pro-Irish republican activist of the most dedicated kind.

As for sailing folk, we simple sons and daughters of the sea and the lakes, we much prefer to think of Erskine Childers only as a brilliant seaman and an eloquent writer about our largely misunderstood and often ignored passion, someone who wrote an alleged spy thriller which was in itself the act of a double agent.

Vixen under sail – remarkably, there is a converted RNLI lifeboat in there somewhere. As Dulcibella, Vixen became the star of Erskine Childers’ best-seller The Riddle of the Sands

Vixen under sail – remarkably, there is a converted RNLI lifeboat in there somewhere. As Dulcibella, Vixen became the star of Erskine Childers’ best-seller The Riddle of the Sands

THE MOST MAGIC SAILING BOOK

For Childers’ novel The Riddle of the Sands – never out of print since it was first published in 1903, and a well-received feature film in 1979 - may seem to the general reader to be a brilliant and subtle warning of how the rapidly rising Germany was building up the potential to have a viable invasion force in Friesland which could cross the North Sea to conquer an unsuspecting England on her weakest flank.

But we amateur sailors know that it is really a superbly-camouflaged description of the special joys of small boat cruising in shallow waters among interesting islands and coastal communities, the most magic sailing book. All the rest of it – the searching around of mysterious new artificial harbours, the avoidance of nosey officialdom, the portrayal of pantomime villains, and (Heaven forbid) the hint of a love interest - all this is only flim-flam to fool civilians into not realising that it is primarily a story about the enduring appeal of genuine amateur cruising in a small boat.

DUN LAOGHAIRE’S ROLE IN CHILDERS’ SAILING

Thus readers in England tend to see Childers’ sailing and its ethos as centrally based in their waters. Yet it all started in Ireland, on the lakes of the Wicklow mountains and in Dublin Bay. For in England, Childers was essentially an orphan from the age of six, when his father died of tuberculosis. His mother was infected, and though she lived for another eight years, it was in a fever hospital in total isolation from her family of two sons and three daughters.

But as his mother was a Barton from Glendalough House at Annamoe in the Wicklow hills, it was there that young Childers and his deprived siblings found a family home among loving relatives after 1883. It was there that they started sailing experiments with their Barton cousins on Lough Dan with sailing canoes and lake boats fitted with rudimentary rigs. And it was from Annamoe at the age of 22 that Erskine Childers and his older brother Henry ventured in 1892 down to what was then Kingstown to meet a noted Royal St George YC member, the renowned helmsman, racing star and rule innovator G B Thompson (later Vice Commodore of Royal St George YC from 1896 to 1920), whose relatively new A E Payne-designed 5.5 Rater Shulah was on the market.

Spring arrives late on the Wicklow hills at Lough Dan, where Erskine Childers started his sailing. Photo Wicklow.ie

Spring arrives late on the Wicklow hills at Lough Dan, where Erskine Childers started his sailing. Photo Wicklow.ie

Thompson felt he’d achieved everything in local racing that he could with Shulah, and it was time to move on to another boat - he owned and campaigned ten in his long sailing career. But he felt Shulah would be ideal to introduce promising newcomers from the right background to the Dublin Bay racing scene, in which he could be their mentor. However, the Childers brothers had other ideas entirely. Their research had shown them that at 8 tons Thames Measurement, with a small cockpit and basic sleeping accommodation below, the 33ft Shulah had the potential to be a handy little fast cruiser.

SUCCESSFUL CORINTHIAN CRUISERS

They’d no personal experience whatever of cruising, and very little, if any, of sea sailing. But “How To” books for neophyte cruisers were increasingly available, and Shulah seemed to tick enough boxes. So though we don’t know if it was Thompson who steered them towards a paid hand/coach to guide them on their first mini-voyages around and from Dublin Bay with Howth being their first “foreign port”, we do know that as the summer of 1892 progressed, they felt sufficiently emboldened to cruise to the Clyde where Shulah was laid up at Gourock with further Scottish cruising planned for 1893. And by that time the Childers brothers reckoned they were better off without a paid hand to assist – they would become true Corinthian cruisers.

Kingstown Harbour in the late 1800s – Erskine Childers’ first cruise – to Scotland – started from here with Shulah in 1892

Kingstown Harbour in the late 1800s – Erskine Childers’ first cruise – to Scotland – started from here with Shulah in 1892

But even as their cruise on up the west coast of Scotland and the Hebrides in 1893 was adding to their experience and enjoyment of sailing, other factors were intervening in their lives. As products of the English upper-ranks education system – Erskine went to public school at Haileybury and university at Cambridge – they sought careers in administrative roles in in London, and after returning to Dun Laoghaire with Shulah, their plan was to get her to the Solent and possibly the Thames Estuary to serve their sailing needs while London-based.

However, adverse weather meant that they got Shulah no further than Plymouth in the Autumn, where she was laid up for the off-season. And through the winter it became evident that the two brothers’ career paths ashore and afloat would be more effectively served by individual boat-ownership, so Shulah – which had been listed in Lloyds Register as solely owned by Henry – was sold to a Plymouth yachtsman.

Erskine’s sailing was now mainly focused on a couple of smaller craft based in the southeast of England with The Netherlands, Belgium and France as possible destinations, and he had soon joined with kindred spirits in the very non-racing Cruising Club (founded 1880 and elevated to Royal Cruising Club in 1902) where he was quickly an active member of the Committee, and the awardee of some cruising trophies - his talent for the entertaining narrative of a mini-voyage was already well-developed.

WATER WAG TO LOUGH DAN

But despite his emerging persona as a young man-about-town in London with enthusiastic outdoor interests at the nearest available countryside and coast, he still felt very strongly drawn to Wicklow, and in 1894 he had arranged the purchase in Kingstown of one of the 1887-founded Dublin Bay Water Wag Class 13ft lug-sailed dinghies, organising its transport to Lough Dan so that it would be available to sail on the almost mystical waters of his youth during his visits home.

A trio of the original 1887 Water Wags. Erskine Childers bought one of these in 1894 for use on Lough Dan when he was visiting home in Wicklow

A trio of the original 1887 Water Wags. Erskine Childers bought one of these in 1894 for use on Lough Dan when he was visiting home in Wicklow

However, with a career in the making as a Clerk - effectively a “Business-of-the-Day Manager” – in the House of Commons in the Westminster Parliament, and with ambitions of becoming a Member of that Parliament in his own right, his life was increasingly London-centric, and very demanding with it. So much so that when the Clerks finally managed to guide the argumentative House’s business to a close for the Summer Recess in 1897, the summer was already well advanced.

In frustration, the briefly boat-less Childers had made the impulse buy of an eccentric little cruising cutter called the Vixen, an ingeniously-converted former RNLI lifeboat with a great big centreboard in the middle of the already limited accommodation. But at least this facilitated the shoal waters cruising which he found increasingly fascinating, and with Autumn already almost upon them, he and some shipmates including brother Henry set off for the Baltic. They soon found themselves among the mysterious Friesian Islands off the northwest coast of Germany, and thus the seed of The Riddle of the Sands was sown.

TOWARDS A CHANGING MIND-SET

Back in London, the setbacks in the Boer War as the 19th Century drew to a close found Childers becoming voluntarily involved with the Honourable Artillery Company, and he served with a special deployment that was sent to serve in South Africa from March to September 1900. In the South African winter – such as it was – this was an increasingly unpleasant experience in a very messy and often unusually cruel war, and Childers returned to England to find himself experiencing his first doubts about the validity and morality of the Imperial Mission.

But nearer home, there was much routine work to be done in Westminster, while the growing stories of Germany’s build-up of her armed forces added urgency to the project of turning the experiences of his 1897 cruise to Friesia into a subtle spy book warning of the dangers of a trans-North Sea invasion. And after much effort and a couple of false trials, it was published in 1903 to universal acclaim and attention in all the right decision-making places.

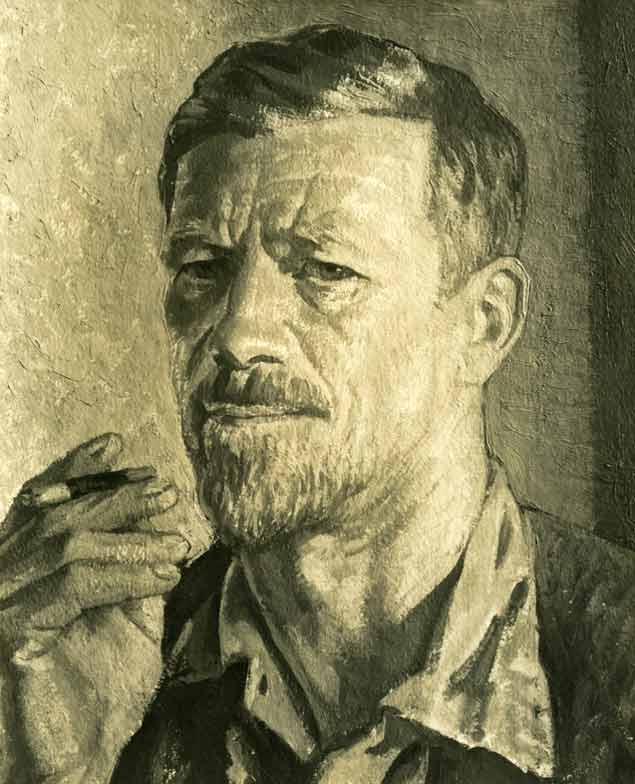

A carefree Erskine Childers – the Victorian sporting man aboard Vixen in 1897

A carefree Erskine Childers – the Victorian sporting man aboard Vixen in 1897

This was a life-changing development. But the greatest life-course changer for Erskine Childers was to come the following year, when the Honourable Artillery Company made its 1904 goodwill visit to Boston. It was the first formal and friendly visit by any unit of the British military to an independent American city, for relations with the new and rapidly growing power on the other side of the Atlantic had often been far from smooth despite the 138 years since Independence from Britain.

Goodwill was in the air, and within days Erskine Childers had met the love of his life, Mary Alden Osgood – known to all as “Molly” - the daughter of one of the leading “Boston Brahmin” families. But in the case of the Osgoods, this was a distinguished and affluent professional family with a notably liberal, generous and distinctly anti-imperialist outlook.

So in finding his soul-mate in Molly Osgood, Erskine Childers had teamed up with a life-partner who would encourage his own increasingly liberal outlook on life, and in particular his nascent interest in Home Rule for Ireland in a movement which was already being enthusiastically espoused by the Barton cousins in the Wicklow hills.

In due course that would all develop, but in the meantime life was joyously taken up with their wedding present from Molly’s parents, the gift of a new 51ft 28-ton cruising ketch to be designed and built to Erskine & Molly’s specifications by a designer and shipwright chosen by Erskine.

Since parting from Vixen – which had become Dulcibella in The Riddle of the Sands - Childers had owned the 15-ton yawl Sunbeam in partnership with a couple of sailing friends, and a cruise to the Baltic which had somehow been fitted into the busy year of 1903 had increased his awareness of the work of the great Norwegian naval architect/shipwright Colin Archer (he was of Scots descent) of Larvik near Oslo.

The Master of Larvik – Colin Archer was in particularly good form when designing and building Asgard for Erskine & Molly Childers in 1905, as Norway was enjoying newly-won independence from Sweden

The Master of Larvik – Colin Archer was in particularly good form when designing and building Asgard for Erskine & Molly Childers in 1905, as Norway was enjoying newly-won independence from Sweden

That cruise had also developed his concept of the ideal cruising yacht, accentuated by experiencing the severe limitations of Vixen, which had reinforced the viewpoint expressed in one of his few sardonic comments about the Boer War: “There are no medals awarded for enduring unnecessary discomfort”.

With the hugely-experienced Colin Archer - who was in a particularly good frame of mind as the keenly-anticipated Norwegian independence from Sweden was finally achieved in 1905 - the 51ft 28-ton Asgard was created in very auspicious circumstances for the newly-weds, becoming one of the most effective yet unpretentious cruising yachts of her day.

And thanks to the many turns which the lives of Erskine and Molly Childers were to take – both together and separately – over the next increasingly turbulent 17 years – today we can admire the conserved Asgard in all her remarkable yet understated glory on exhibition in the Collins Barracks Museum in Dublin.

The conserved Asgard on display in Collins Barracks, with conservator John Kearon explaining to a group of cruising enthusiasts how the project of saving her was successfully completed. Photo: W M Nixon

The conserved Asgard on display in Collins Barracks, with conservator John Kearon explaining to a group of cruising enthusiasts how the project of saving her was successfully completed. Photo: W M Nixon

As to how she comes to be there, we’ll assume general knowledge of her key role in the July 1914 gun-running to Howth in support of the much-promised but often delayed Home Rule for Ireland. We’ll assume, too, that you know that all the main actors in the three yachts involved in the total gun-running project immediately signed up for service with the allied forces in the Great War which broke out wihin days of the guns coming ashore in Howth and Wicklow.

And we’ll take it as a given that you’re aware that after the Easter Rising of 1916, Childers was taken out of his be-medalled service in the war in order to be a line of contact between the opposing forces both within Ireland, and between Ireland and London.

The Great War ended in November 1918 to become known – all too soon – as World War I. And in Ireland the scene had moved forwards towards the End Game with a Sinn Fen landslide in the south and west of the country in a General Election which provided such a powerful mandate that the SF members refused to take up their seats in London’s Westminster parliament.

Instead, the first Dail was established in Dublin’s Mansion House and a remarkable parallel alternative administration began to develop throughout the nationalist-majority areas of Ireland. It was headed by Michael Collins, as Eamonn de Valera was away in the USA fund-raising, and Erskine Childers worked for it in the unsubtly-named Department of Propaganda, while his fellow former gun-runner, Conor O’Brien, was recruited with his ketch Kelpie to be a Fisheries Inspector off the West Coast.

But inevitably this measured approach had already proven too slow for the more impatient Home Rulers or advocates of total Independence, and the War of Independence was soon messily under way. Yet the underlying strength of the Provisional Government was demonstrated in its continuing functioning, even to having alternative law courts which many communities found to be much more effective than the occasionally convened and often totally ignored British ones.

And in the Department of Propaganda, working anonymously, Erskine Childers was in his element. Any respected international journalist who had shown the slightest fair-minded attitude to the situation was given every assistance in coming to Ireland and developing his or her stories.

The American and other journalists whom he brought over were impressed by his professionalism, thoroughness and thoughtfulness in trying to help them provide an accurate overview of the situation. His personal problem was that British politicians and their imperialist press – with whom he would otherwise have got on reasonably well as an equal - regarded him as a complete traitor. The fact that he’d written the popular and influential Riddle of the Sands only added to their confusion and annoyance.

Making history – Asgard departing Howth after the successful landing of the guns on Sunday July 26th 1914 which – contrary to the account in some histories – was not at all a warm summery day. She is setting a gaff-headed trisail as her mainsail had been torn during the unloading of the guns

Making history – Asgard departing Howth after the successful landing of the guns on Sunday July 26th 1914 which – contrary to the account in some histories – was not at all a warm summery day. She is setting a gaff-headed trisail as her mainsail had been torn during the unloading of the guns

At the other end of the spectrum, the more extreme Irish republicans with whom he was supposed to work in harmony were profoundly suspicious of him as a potential spy, and they disliked him instinctively as being an obvious member of the Ascendancy landlord class, for all that the Bartons in Wicklow had been model landlords.

And then, too, he had become someone with whom people could not comfortably feel at ease in a professional situation. His ultimately totally uncompromising attitude was occasionally hinted at, despite the supposed affability of propaganda work. Long gone was the jolly life-exuding young skipper who had sailed out with his friends in that crazy cruise with the Vixen in 1897. In their place was someone who, even when off duty, had the harrowed look of a man who had an inescapable date with destiny.

It would be easy to talk of Erskine Childers in 1920 as being on an unalterable course towards that appointment with the firing squad two years later. Yet now a hundred years later, it helps us to come to terms with what looks like a terrible waste, the totally untimely end to an exceptional talent at the age of 52 when he had come through so much, he had given so much, and surely – had things been very different - could have learned again how to enjoy and give as he had in times past.

Towards dawn on November 24th 1922, he asked for an extra hour so that he could see the sun come up on his beloved Wicklow hills above the dark lake where his little sailing dinghy nestled in its winter shelter. And already that sun shone on Snowdonia in Wales, beneath whose peaks in the boatyard beside the Menai Straits, his beloved Asgard still rested, stored undisturbed since the events of July 1914. Then Erskine Childers turned, and in his awkward yet gentle way, he helped the firing squad to do their duty.

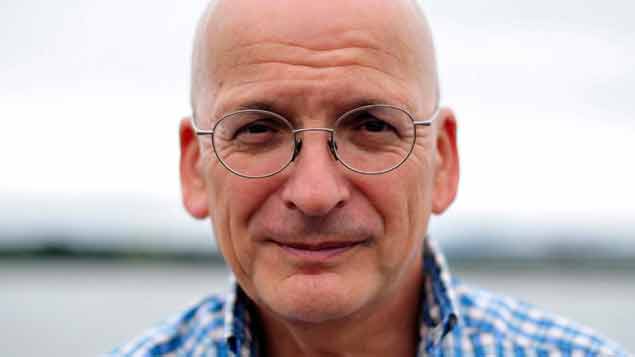

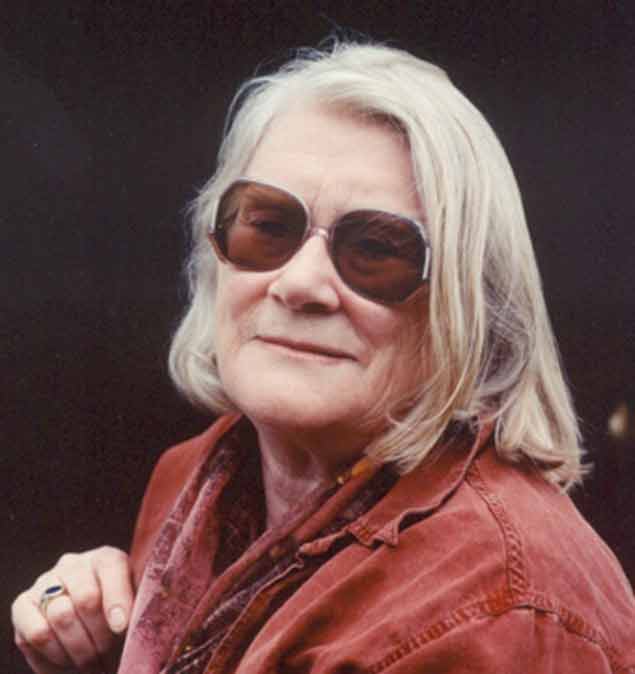

Dun Laoghaire Bookfest Stars Roddy Doyle & Jennifer Johnston - Irish Writers With an Unexpected Nautical Connection

“Only connect” urged the novelist E M Forster writes W M Nixon. But his idealistic concepts of emotional connection would be at some remove from the curiously coincidental nautical connections between writers Roddy Doyle and Jennifer Johnston, who are in public conversation for an hour on the final day of this week’s “Mountains to the Sea” dlr Book Festival in Dun Laoghaire.

Roddy Doyle is married to a direct descendant of Erskine Childers. And Jennifer Johnston is in private life Mrs Gilliland, married into a noted Derry family long involved with boats. Erskine Childers was of course best known as author of the 1903-published maritime thriller The Riddle of the Sands before he acquired fame as skipper of the Asgard in the 1914 Howth gun-running. And at that time, the leading sailor in the Gilliland family was Frank Gilliland, who was a pioneer in producing sailing directions and small boat charts for the northwest of Ireland, particularly Donegal, and recently came up on the radar again with Robbie Mason of Milford Haven undertaking a restoration of his 1938 Scottish fishing boat-style motor cruiser Blue Hills.

Both Childers and Gilliland were members of the oldest cruising organisation in the world, the 1880-founded Royal Cruising Club. But although both served in various sections of the Royal Naval Reserve through the 1914-18 War, by the time that war ended they had very different notions as to the future of Ireland in the post-war turbulence which eventually led to the War of Independence, the Partition which created Northern Ireland in 1921, and the Civil War in the new Irish Free State. Yet while they may have viewed some things very differently, in 1919 they combined on a small but significant project which was to have longterm effects on Irish sailing.

Both were acquainted with a sailor from Foynes called Conor O’Brien, Gilliland probably through the Naval Reserve connections, while Childers knew O’Brien from the time he had brought his ketch Kelpie along to assist in the 1914 gun-running. Whatever their origins, the connections were such that when the Foynes man sought to join the Royal Cruising Club in September 1919, he was proposed by Frank Gilliland and seconded by Erskine Childers, and duly got in.

Looked at across the series of events which occurred before and since, it was an extraordinary and unlikely combination of people and purposes. But it meant that Conor O’Brien now had access to a recognised channel for acknowledgement of his cruising achievements, which became serious when he departed Dun Laoghaire on June 20th 1923 for his voyage round the world south of the Great Capes with the new 42ft Baltimore-built Saoirse.

By this time, Erskine Childers had been executed by a firing squad of the Government of the new Irish Free State as an armed anti-Treaty rebel. And Frank Gilliland was on his way to becoming the Aide-de-Camp to the first Governor of Northern Ireland. But O’Brien sailed blithely along on his epic voyage, flying the tricolour ensign of the new Irish state whenever possible, yet submitting logs each year to the annual competition of the Royal Cruising Club.

Although many members of the RCC had severe doubts about having anything whatever to do with the new Ireland, the hugely-experienced adjudicator Claud Worth, RCC Vice Commodore, had little hesitation in awarding O’Brien the club’s premier trophy, the Challenge Cup, three years on the trot in recognition of his remarkable achievement.

Not only that, but when O’Brien wrote his book Across Three Oceans about the voyage, Claud Worth willingly supplied a foreword which gave the entire venture an official status which it has held ever since. In it, he memorably commented:

“Mr O’Brien’s plain seamanlike account is so modestly written that a casual reader might miss its full significance” wrote Worth. “But anyone who knows anything of the sea, following the course of the vessel day by day on the chart, will realize the good seamanship, vigilance and endurance required to drive this little bluff-bowed vessel, with her foul uncoppered bottom, at speeds from 150 to 170 miles per day, as well as handling the weight of wind and sea which must sometimes have been encountered”.

This level of support from a man regarded as God-like in his wisdom by the world of cruising was the ultimate level of recognition, and O’Brien’s reputation was secure, regardless of the fact that some found him at personal level to be a leading member of the Awkward Squad. It’s possible that his achievements were such that he would have so impressed Claud Worth regardless of his RCC membership. But the fact that he’d become a member in 1919 – albeit with the most unlikely combination of supporters – had greatly smoothed the way.

And as next Sunday’s exchange of ideas between Jennifer Johnston and Roddy Doyle is taking place beside the harbour where Saoirse’s great voyage began and ended over the space of exactly two years between 1923 and 1925, the coincidences are complete. Their conversation is on Sunday March 25th at noon in dlr Lexicon Level 4, booking recommended.

A New Tall Ship For Ireland? It's Back to The Future

#tallship – The Tall Ships return to Ireland in spectacular style this summer with a major fleet assembly in Belfast from Thursday 2nd to Sunday 5th July for the beginning of the season's Tall Ships Races, organised by Sail Training International. The seagoing programme will have a strong Scandinavian emphasis in 2015, with the route - some of which is racing, other sections at your own speed – starting from Belfast to go on Aalesund in western Norway for 16th to 18th July, thence to Kristiansand (25th to 28th July), which is immediately east of Norway's south point, and then on to conclude at Aalborg in northern Denmark from 1st to 4th August.

But before leaving Northern Ireland with the potentially very spectacular Parade of Sail down Belfast Lough on Sunday July 5th, the celebrations will be mighty. The fleet's visit will be the central part of the Lidl Belfast Titanic Maritime Festival, which will include everything from popular family fun happenings with concerts and fireworks displays – the full works, in other words – right up to high–powered corporate entertainment attractions.

As for the ships, there will be more than enough for any traditional rig and tall ship enthusiast to spend a week drooling over. In all, as many as eighty vessels of all sizes are expected. But more importantly, at least twenty of them will be serious Tall Ships, proper Class A square riggers of at least 40 metres in length, which is double the number which took part in their last visit to Belfast, back in 2009.

That smaller fleet of six years ago seemed decidedly spectacular to most of us at the time. So the vision of a doubling of proper Tall Ship numbers in Belfast Harbour is something we can only begin to imagine. But when you've a fleet which will include Class A ships of the calibre of the new Alexander von Humboldt from Germany, Norway's two beauties Christian Radich and Sorlandet, the much-loved Europa from the Netherlands, George Stage from Denmark, and the extraordinary Shtandart from Russia which is a re-creation of an 18th Century vessel built for Emperor Peter the Great, you're only starting, as that's to name only six vessels – what we'll be seeing will be a truly rare gathering of the crème de la creme.

So although it would be stretching it to think that a small country like Ireland should aspire to having a major full-rigged vessel, we mustn't forget that for 27 glorious years we did have our own much-admired miniature Tall Ship, the gallant 84–ft brigantine Asgard II. Six-and-a-half years years after her loss, it's time and more for her to be replaced. W M Nixon takes a look at what's been going on behind the scenes in the world of sail training in Ireland and finds that, in the end, we may find ourselves with a ship which will look very like a concept first aired for Irish sail training way back in 1954.

The pain of it. You search out a photo of Shtandart, the remarkable Russian re-creation of an 18th century ship, and you find that Asgard II is sailing beside her

It was while sourcing a photo of Russia's unusual sail training ship Shtandart that the pain of the loss of Asgard II emerged again. It's always there, just below the surface. But it's usually kept in place by the thought that we have to move on, that worse things happened during the grim years of Ireland plunging ever deeper into recession, and that while our beloved ship did indeed sink, no lives were loss and her abandonment was carried out in an exercise of exemplary seamanship.

Yet up came the photo of the Shtandard, and there right beside her was Asgard II, sailing merrily along on what's probably the Baltic, and flying the flag for Ireland with her usual grace and charm. The pain of seeing her doing what she did best really was intense. She is much mourned by everyone who knew her, and particularly those who crewed aboard her. All three of my sons sailed on her as trainees, they all had themselves a great time, and two of them enjoyed it so much they repeated the experience and both became Watch Leaders. It was very gratifying to find afterwards, when you went out into the big wide world and put "Watch Leader Asgard II" on your CV, that it counted for something significant in international seafaring terms.

But as a sailing family with other boat options to fall back on, we didn't feel Asgard II's loss nearly as acutely as those country folk for whom the ship provided the only access to the exciting new world of life on the high seas.

Elaine Byrne vividly recalls how much she appreciated sailing on Asgard II, and how she and her siblings, growing up in the depths of rural Ireland, came to regard the experience of sailing as a trainee on the ship as a "Rite of Passage" through young adulthood

The noted international investigative researcher, academic and journalist Dr Elaine Byrne is from the Carlow/Wicklow border, the oldest of seven children in a farming family where the household income is augmented with a funeral undertaking business attached to a pub in which she still occasionally works. Thus her background is just about as far as it's possible to be from Ireland's limited maritime community. Yet thanks to Asgard II, she was able to take a step into the unknown world of the high seas as a trainee on board, and liked it so much that over the years she spent two months in all aboard Asgard II, graduating through the Watch Leader scheme and sailing in the Tall Ships programmes of races and cruises-in-company

Down in the depths of the country, her new experiences changed the Byrne family's perceptions of seafaring. Elaine Byrne writes:

"Four of my siblings (then) had the opportunity to sail on Asgard II. If it were not for Asgard II, my family would never have had the chance to sail, as we did not live near the sea, nor had the financial resources to do so. The Asgard II played a large role in our family life as it became a Rite of Passage to sail on board her. My two youngest siblings did not sail on the Asgard II because she sank, which they much regret".

She continues: "Apart from the discipline of sailing and the adventure of new experiences and countries, the Asgard brought people of different social class and background together. There are few experiences which can achieve so much during the formative years of young adulthood"

That's it from the heart – and from the heart of the country too, from l'Irlande profonde. So, as the economy starts to pick up again, when you've heard the real meaning of Asgard II expressed so directly then it's time to expect some proper tall ship action for Ireland in the near future. But it's not going to be a simple business. So maybe we should take quick canter through the convoluted story of how Asgard II came into being, in the realization that in its way, creating her successor is proving to be every bit as complex.

As we shall see, the story actually goes back earlier, but we'll begin in 1961 when Erskine Childers's historic 1905-built 51ft ketch Asgard was bought and brought back by the Irish government under some effective public pressure. It was assumed that a vessel of this size – quite a large yacht by the Irish standards of the time – would make an ideal sail training vessel and floating ambassador. It was equally assumed that the Naval Service would be happy to run her. But apart from keen sailing enthusiasts in the Naval Reserve - people like Lt Buddy Thompson and Lt Sean Flood – the Naval Service had enough on its plate with restricted budgets and ageing ships for their primary purpose of fishery patrol.

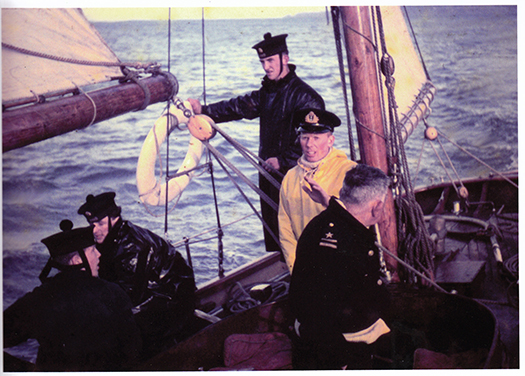

Aboard the first Asgard in 1961 during her brief period in the 1960s as a sail training vessel with the Naval Service – Lt Sean Flood is at the helm

So Asgard was increasingly neglected throughout the 1960s until Charlie Haughey, the new Minister for Finance and the only member of Government with the slightest interest in the sea, was persuaded by the sailing community that Asgard could become a viable sail training ship. In 1968 she was removed from the remit of the Department for Defence into the hands of some rather bewildered officials in the Department for Finance, and a voluntary committee of five experienced sailing people - Coiste an Asgard - was set up to oversee her conversion for sail training use in the boatyard at Malahide, which just happened to be rather less than a million miles from the Minister's constituency.

Asgard in her full sail training role in 1970 in Dublin Bay

Asgard was commissioned in her new role in Howth, the scene of her historic gun running in 1914, in the spring of 1969. Under the dedicated command of Captain Eric Healy, the little ship did her very best, but it soon became obvious that her days of active use would be limited by reasons of age, and anyway she was too small to be used for the important sail training vessel roles of providing space to entertain local bigwigs and decision-makers in blazers.

By 1972, the need for a replacement vessel was a matter of growing debate in the sailing community, and during a cruise in West Cork in the summer of 1972, I got talking to Dermot Kennedy of Baltimore out on Cape Clear. Dermot was the man who introduced Glenans to Ireland in 1969, and then he branched out on his own in sail training schools. A man of firm opinions, he reacted with derision to my suggestion that Asgard's replacement should be a modern glassfibre Bermudan ketch, but with enough sails to keep half a dozen trainees busy.

"Nonsense" snorted Dermot. "Ireland needs a real sailing ship, a miniature tall ship maybe, but still a real ship, big enough to carry square rig and have a proper clipper bow and capture the imagination and pride of every Irish person who sets eyes on her. And she should be painted dark green just to show she's the Irish sail training ship, and no doubt about it".

Some time that winter I simply mentioned his suggestions in Afloat magazine, and during the Christmas holidays they were read by Jack Tyrrell at his home in Arklow. During his boyhood, in the school holidays he had sailed with his uncle on the Arklow schooner Lady of Avenel, and it had so shaped his development into the man who was capable of running Ireland's most successful boatyard that he had long dreamed of a modern version of the Lady of Avenel to be Ireland's sail training ship.

The inspiration – Jack Tyrrell's boyhood experiences aboard Lady of Avenel inspired him to create Ireland's first proper sail training ship

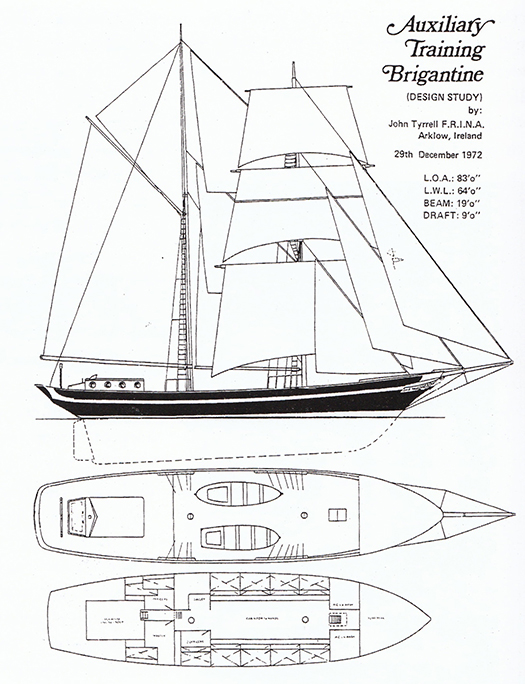

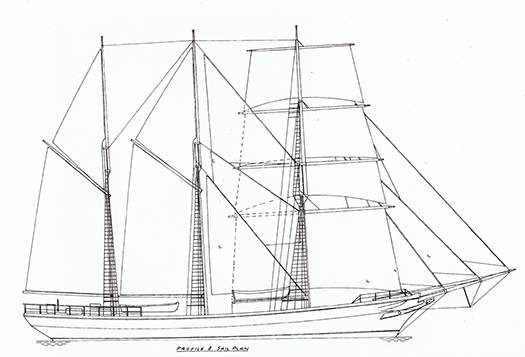

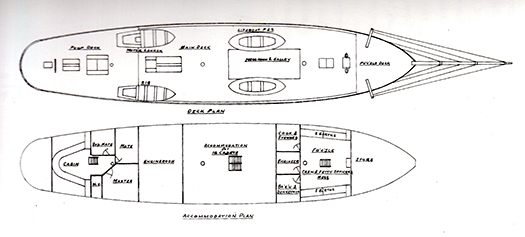

In fact, in 1954 he had sketched out the plans for a 110ft three masted training ship, but Ireland in the 1950s was in the doldrums and the idea got nowhere. Yet the spark was always there, and it was mightily re-kindled by what Dermot Kennedy had said. So at that precise moment, the normal Christmas festivities in the Tyrrell household were over. They'd to continue the celebrations without the head of the family. The great man took himself off down to the little design office in his riverside boatyard, and in clouds of pipe tobacco smoke, he re-drew the lines of the 110ft three master to become an 83ft brigantine, the size reduction meaning that the shop would only need a fulltime crew of five.

Working all hours, he had the proposal drawings finished in time to rejoin his family to see in the New Year. And in the first post after the holiday, we got the drawings at Afloat, and ran them in the February 1973 issue.

Jack Tyrrell's proposal drawings for the new brigantine, as published in the February 1973 Afloat

In Ireland then as now, most politicians had inscribed in their heads the motto: "There's No Votes In Boats". So after Charlie Haughey had fallen from favour with the Arms Trial of 1970, Coiste an Asgard became an orphan. But 1973 brought a new government, and there was one cabinet minister in it who was proud to proclaim his allegiance to the sea.

Unfortunately for the respectability of the maritime movement in Ireland, our supporters in the higher echelons of politics have often tended to be from the colourful end of the political spectrum, whatever about their placing in the left-right continuum. Thus it was that, at mid-morning on St Patrick's Day 1973, I got an ebullient phone call and an immediate announcement, without the caller saying who he was. "Winkie" he bellowed, "That ship is going to be built. I'll make sure of it. I've just made a ministerial decision".

It emerged that it was our very own new Minister for Defence, Patrick Sarsfield Donegan TD. The enthusiasm for the new ship, engendered by studying Jack Tyrrell's drawings, led to a snap decision which stayed decided, and it all happened in the Department for Defence.

However, it was 1981 by the time the ship was launched, and she looked rather different from Jack Tyrrell's preliminary drawings, though the basic hull shape built in timber was the same sweet lines as originally envisaged, so she was able to sail like a witch. But as for her supporters at Government level, the non-stop cabaret continued. Charlie Haughey had regained power, and by 1981 he was Taoiseach. It was he who had seen to it that the Department of Defence continued to look after the Asgard II project with support from another sailing TD who might not have seen eye–to-eye with him on other matters, Bobby Molloy of Galway.

Asgard II in her finished form

So on a March day in 1981, almost exactly twelve years after he'd commissioned the original Asgard in her new role as a sail training vessel, Charlie Haughey took it upon himself to christen the new Asgard II in Arklow basin. And the champagne bottle refused to break. Five or six time he tried, but with no success.

Showing considerable grace under pressure and observed by a large crowd, he quietly took his time undoing all the ribbons and paraphernalia on the big bottle. Then he marched with it up to the new flagship's stem, and hit it a mighty double-handed wallop. The bottle exploded that time, with no mistake. And apart from the usual Haughey growl to those nearby about the idiocy of whoever forgot to score the champagne bottle beforehand, it was all done with the best of humour.

For most of her subsequent career, there's no doubt Asgard was a lucky and very successful vessel. Yet when her demise came, you couldn't help but think of the old notion that if the champagne bottle doesn't break first time, then she'll ultimately be an unlucky ship.

But there are more prosaic explanations. With a limited budget and every penny being scrutinized, Jack Tyrrell and his men had to build Asgard II in fishing boat style, which is fine within its proper time span, but that time span is really only twenty years, maybe thirty if the ship gets extra care. But with her fishing boat hull carrying a demanding brigantine rig, although she always looked immaculate, Asgard II was starting to show her age in the stress areas.

By 2005 there was serious talk about the need to plan for a replacement. When her skipper Colm Newport was told to renew her rig as the original spars were clearly well past it, he meticulously searched the best timber yards at home and abroad and when she got her new rig – it was 2006 or thereabouts – I wrote an only slightly tongue-in-cheek article suggesting that now was the time to replace her old tired wooden hull with a new steel one to the same Jack Tyrrell lines, but utilising the excellent new rig and as many of the fixtures and fittings as were still in good order from the original ship.

To say the response was negative is understating the case. People's attachment to Asgard could only imagine a wooden ship. It was the end of any meaningful debate. So things drifted on, with each new government seemingly even less interested in maritime matters generally, and sail training in particular, than the one before.

In September 2008, Asgard started taking in water while on passage with a crew of trainees towards La Rochelle for a maritime festival following which - while still in La Rochelle – it was planned that she would be lifted out for a thorough three week survey and maintenance programme.

Asgard's accommodation worked superbly whether at sea or in port. But the fact that so much was packed into a relatively small hull meant that some areas were almost inaccessible for proper inspection

It might have been the saving of her. But it was not to be. It's said that it was a failed seacock which caused the catastrophic ingress of water. She was a very crowded little ship, she packed a lot into her 84ft, so some hull fittings were less accessible internally than they would be in a more modern vessel, and may have deteriorated to a dangerous level. But if, as some would propose, she hit something in the water which caused a plank to start, then the fact that nobody aboard was aware of any impact suggests that the time for a major overhaul, and preferably a hull replacement, was long overdue.

The moment Asgard II sank, she ceased to have any future as a sail training vessel, and there was no real official interest in her salvage. You simply cannot take other people's children to sea on a salvaged vessel of doubtful seaworthiness. And as it happens, the sinking came at exactly the time the Irish economy fell of a cliff. So although after an enquiry the Government accepted a €3.8 million insurance settlement, in the end, despite assurances to the contrary, it disappeared into the bottomless pit which was the national debt, and within a year Coiste an Asgard was wound up with its records and few resources incorporated into a new entity, Sail Training Ireland.

The plot takes a further macabre twist in that, shortly after the loss of Asgard II, the Northern Ireland Sailing Training ketch was also lost after hitting a rock on the Antrim coast. From having two popular and well-used sail training vessels in the middle of 2008, within a year Ireland had no official sail training vessels at all.

Yet though the flame had been largely subdued, there were those who have kept the faith, and gradually the sail training movement is being rebuilt. Sail Training Ireland is the frontline representative for around five different organisations, being the official affiliate of Sail Training International, and it has a busy programme of placing trainees in ships which operate at an international level, in which the Dutch are supreme.

In Ireland at the moment, the only sail training "ship" is the schooner Spirit of Oysterhaven, run by Oliver Hart and his team from their adventure centre near Kinsale. In fact, Spirit – you can read about her in Theo Dorgan's evocative book Sailing For Home (Penguin Ireland 2004) – really is punching way above her weight in representing Ireland in a style reminiscent of both the Asgards.

Spirit of Oysterhaven has been doing great work in keeping sail training alive in Ireland

But having the ship is one thing, paying the fees for the trainees to be aboard is something else, and sail training bursaries are one of the key areas of expansion in current maritime development in Ireland. There was an unusual turn to this in 2014 when somebody came up with the bright idea of using Irish Cruising Club funds (which are generated by the surplus from the voluntary production of the club's Sailing Directions) to provide bursaries for youngsters to take part in last summer's ICC 85th Anniversary Cruise-in-Company along the southwestern seaboard on Spirit of Oysterhaven.

The idea worked brilliantly, and this concept of neatly-tailored sail training bursaries is clearly one which can be usefully developed. But still and all, while it's great that young Irish people are being assisted in getting berths aboard charismatic vessels like Europa, the feeling that we should have our own proper sail training ship again is gradually gaining traction, and this is where the Atlantic Youth Trust comes in.

The AYT had its inaugural general meeting in Belfast as recently as the end of September 2014, so it may not yet have come up on your radar. But as it has emerged out of the Pride of Ireland Trust which in turn emerged from the Pride of Galway Trust, you'll have guessed that Enda O'Coineen and John Killeen are much involved, and they've roped in some seriously heavy hitters from both sides of the border, either as Board Members or backers, and sometimes as both.

The cross-border element is central to the concept of building a 40 metre three-masted barquentine, a size which would put her among the glamour girls in Class A, and could carry a decidedly large complement of 40 trainees, even if you're inevitably talking of stratospheric professional crewing costs.

However, by going straight in at top government level on both sides of the border, the AYT team are finding that they're pushing at a door which wants to open, particularly after the new Stormont House agreement was reached in the last days of 2014 to bring a more enthusiastic approach both to cross-community initiatives in the north, and cross border co-operation generally.

Who knows, but if they can succeed in getting cross-community initiatives working in Northern Ireland, then they may even be able to swing some sort of genuine Dublin-Cork shared enthusiasm in the Republic, for I've long thought that one of the factors in holding back many maritime initiatives in Ireland is that, while Dublin may be the political capital, Cork is quietly confident it's the real maritime capital, and does its own thing.

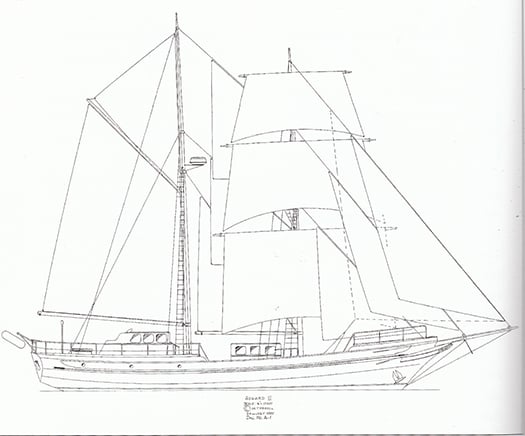

Be that as it may, the AYT have done serious studies, and their conclusion is the best scheme to learn from is the Spirit of Adventure programme in New Zealand. This is where the feeling of going back to the future arises, for in looking at photos of their ship Spirit of New Zealand, there's no escaping the thought that you're looking at Jack Tyrrell's concept ship of 1954 brought superbly to life.

Spirit of New Zealand

Spirit of New Zealand almost seems like a vision of 1954 brought to life...

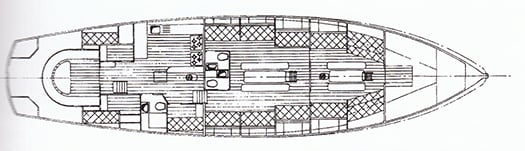

.....and that vision is Jack Tyrrell's 1954 concept for a 110ft sail training ship

The 1954 accommodation drawings for the 110ft ship hark back to a more rugged age. Imagine the difficulties the ship's cook would face trying to get hot food from his galley on deck amidships all the way back to the officers in their mess down aft

We needn't necessarily agree with all the AYT's basic thinking For instance, they assert that Ireland is like New Zealand is being an isolated smallish island. It depends what you mean by "isolated". Those early sail training pioneers, the Vikings, certainly didn't think of Ireland as isolated. They thought it was central to the entire business of sailing up and down Europe's coastline.

Thus any all-Ireland sail training vessel would be expected to be away abroad at least as much as she'd be at home, whereas Spirit of New Zealand is usually home – the season of 2013-2014 was the first time she'd been to Australia since 1988, when she was in the fleet with Asgard II for the First Feet celebrations.

In New Zealand, she's a sort of floating adventure centre, and a large tender often accompanies her to take the trainees to the nearest landing place for shoreside adventures, for it's quite a challenge keeping 40 energetic young people fully occupied.

In Europe, that's where the sail training races come in. Time was when the racing aspect was down-played. But there's nothing like a good race to bring a mutinous crew together, and the recently-published mega-book about the world's sail training vessels, Tall Ships Today by Nigel Rowe of Sail Training International, quite rightly devotes significant space to everything to do with the racing.

Thus if we do get a new sail training ship for Ireland, she'll have to sail well and fast. That was Asgard II's greatest virtue. For there is nothing more dispiriting for troubled young folk than to find themselves shackled to the woofer of the fleet. Yet you'd be pleasantly surprised by how previously disengaged youngster can become actively and enthusiastically involved when they find that they're being transformed from scared and seasick kids into members of a winning crew.

So now, the 64 thousand dollar question. The cost. It's rather more than 64 thousand. AYT reckon they'll have to come up with a final capital expenditure of €15 million to build the ship and get her into full commission with proper crewing and shoreside administration arrangements in place. But after that – and here's the kernel of the whole concept – they reckon that the running costs will come out of existing government expenditure already in place and used every year for education, youth training, sporting facilities, social development and so forth.

So their pitch is that if the governments north and south come up with funding to support substantial donations already proposed for AYT by various benevolent national and international bodies, then once the ship is in being, she will generate her own income in the same way as vessels like Europa and Morgen Stern are already doing in mainland Europe.

And it's to the heart of mainland Europe that they'll be looking for design and contruction, as it's the Dykstra partnership which will be overseeing the design, and their ship-build associate company Damen will likely do the construction work, though one idea being floated is that Damen might provide a flatpack kit for the vessel to be built in steel in Ireland.

Those of us who dream of Asgard II being built anew will find all this a bit challenging to take on board. My own hopes, for instance, would still be to build Asgard II again to Jack Tyrrell's lines, but with the hull constructed in aluminium. It would be expensive as it would need to be double-skin below the waterline, but the ship's size would be very manageable with a professional crew of just five, while she'd sail like a dream And proper top-class marine grade aluminium seems to last for ever, as naval architect Gerry Dijkstra (his surname is slightly different from that of the partnership) himself shows with his remarkable cruises with his own-designed alloy 54-footer Bestevaer.

A man who knows what he's doing. This is Gerry Dijkstra's own extensively-cruised alloy-built 54 footer Bestevaer. The name translates not as "Best ever", but either as "best father" or "best seafarer", and was the name of affection given to the great Admiral de Ruyter by his loyal crews

Whatever, the good news is that things are on the move, and we wish them well, all those who have kept the Irish sail training flame alive through some appalling setbacks. Now, it really is the time to move forward. And if we do get a new ship, why not call her the Jack Tyrrell? He, of all people, was the one who kept the faith and the flame alive.

- Tall ship

- Belfast

- Jack Tyrell

- Kristiansand

- Aalesund

- Titanic

- maritime

- Class A

- square riggers

- George Stage

- Alexander Von Humboldt

- Christian Radich

- Sorlandet

- Shtandart

- Brigantine

- Asgard II

- Elaine Byrne

- Erskine Childers

- Sean Flood

- Naval

- Afloat magazine

- boatyard

- sail training ship

- Coiste an Asgard

- Charlie Haughey

- Colm Newport

- Irish Cruising Club

- Spirit of Oysterhaven

- Enda O'Coineen

- John Killeen

- Dykstra

Conserving Historic Vessels

John Kearon – who is himself from Arklow – is one of the foremost in this field, with a distinguished career centred on the historic ships programme in Liverpool. His patient work, in making Asgard a non-seagoing conserved version of the vessel as she was when Erskine and Molly Childers had her built as a wedding present from her Molly's father, has clarified design features which had been lost in alterations made in the 1930s and the 1960s.

John Kearon with Asgard in Collins Barracks at an early stage of the conservation. Photo: W M Nixon

The quality of his research and craftsmanship has also helped in deciding Asgard's future. It is right that she should be conserved rather than restored. But if any group wishes to build a sailing replica, then the definitive plans are now available.

The features on aspects of Asgard's conservation are only part of a very comprehensive extensively illustrated book which covers historic ships and boats of any types. Naturally there's a significant element of serious academic insight. But those of us who are fascinated by all craft immediately warm to a learned volume which, despite its adherence to historical rigour and correctness, nevertheless refers to each vessel as "she".

WMN

Understanding Historic Vessels-Volume 3

Published by National Historic Ships, £30.

www.nationalhistoricships.org.uk