Displaying items by tag: Irish Cruising Club

Jennifer Guinness 1937–2016

Jennifer Guinness was one of the most accomplished Irish amateur sailors of her generation. Her death at the age of 78, after a gallant battle with cancer, brings to an end an extraordinary life in which she was sometimes unwillingly in the full glare of public attention, yet she was never happier than with a few friends and family in an informal and private setting, whether at home or on a boat.

She was of a very maritime family - her father Colonel J B Hollwey was a leading figure in Dublin Bay sailing and also a noted pioneer in shipping, with his company Bell Lines being in the forefront of the international development of containerisation. Many of her earliest memories were of sailing from childhood, and she became experienced in every aspect of the sport, whether as helm or crew, inshore and offshore, racing and cruising.

With marriage to merchant banker John Guinness of Howth, she moved across Dublin Bay to live on the Baily and sail from Howth Harbour, and their shared love of sailing found fulfillment in the Folkboat Sharavoge, the McGruer 43ft yawl Sule Skerry, and then their final boat together - the Hood 50 ketch Deerhound. While she was a very supportive consort for John in his roles as Commodore of Howth Yacht Club and then Commodore of the Irish Cruising Club, for Jenny Guinness the real point of it all was to go sailing as much as possible, whether it was racing at every opportunity in a variety of boats – she was a noted helm in the International Dragon Class - or cruising extensively, with their range of places visited in detail taking in Spain to the south and the far reaches of Scandinavia to the north, all cruised in notably well-planned and competent ventures.

Her competitive instincts were also taken offshore – in 1975 she was a member of the Irish Admirals Cup team as crew on board Clayton Love Jnr’s Swan 44 Assiduous, and in 1986 she was a crewmember on Robin Knox-Johnston’s 60ft catamaran British Airways in a successful challenge for the Round Ireland Record.

She and John also occasionally raced Deerhound offshore, though the big ketch was essentially a cruising boat. But this didn’t restrain them from hard-driving of the ship, and a classic memory of Jenny Guinness is of a stormy cross-channel race from Howth to Holyhead in 1977. As was usual when the boat was racing, she was on the helm, but it was the crew’s decision to set the mizzen staysail.

In a fierce squall, the entire mizzen mast setup, complete with billowing staysail, collapsed around her. Yet not only was she miraculously unscathed, but she blithely continued steering, helming on from amidst the ruins of the rig while crisply telling her husband and the rest of the crew that as they had decided to put up the extra sail, it was their job to tidy up the resulting mess - she meanwhile had some serious sailing to do, as the wind was by now hitting gale force, they’d a race to finish, and the mainmast was still standing and working well. Having started the race as a ketch, Deerhound finished it as a sloop.

It’s a cold wet night in May 1986, but the big catamaran is on track to a new Round Ireland Record, the helmsman has the boat going sweetly, and in the tiny cabin Jenny Guinnness decides that the watch below need a little whiskey as a warmer, and Josh Hall and Robin Knox-Johnston agree. Photo: W M Nixon

For most of their life together, she and John lived in the characterful old family home of Ceanchor House overlooking Dublin Bay and the Wicklow Hills – it was a centre of informal and generous hospitality on an often international scale, frequently and boisterously filled with sailing friends from near and far. They were also raising a family, and while there had been extreme challenges such as her kidnapping in 1986, underneath her sometimes shy exterior she was one very tough person, and she emerged successfully, and if anything stronger than ever, from experiences which would have defeated a lesser individual.

Her most devastating test came in 1988, when John was tragically killed in a mountain-walking accident in Snowdonia. The gallantry of her response to this personal disaster was inspirational. In time, she was back afloat, and moved on from Deerhound to two boats which were very definitely an expression of Jenny Guinness’s view of sailing, as they were formidable performance cruisers, both called Alakush - the first a very speedy Humphreys-designed Sovereign 400, the second a handsome Sabre 426.

Sailing these fine boats, she continued her stylish progress across the sea in racing and cruising, supported by family and a loyal group of friends who relished the challenge of sailing with a determined skipper whose exceptional ability at the helm was well matched by her creative skill in the galley. Her zest in the sport was restricted only by the onset of arthritis in her latter years, which she found exasperating, but battled in typically doughty style.

She faced the final challenge of terminal cancer with the same gallantry. She was determined to see Christmas 2015 despite medical expectations to the contrary, and she did it in style for a “truly magical” Christmas in the midst of a large party of extended family and close friends, most of them shipmates too. This well-lived life has now come to an end, and our heartfelt condolences go to Jennifer Guinness’s husband Alex Booth, her family and her many friends.

WMN

Justin Slattery Awarded Top Irish Cruising Club Honour

Double Volvo Ocean Race winner Justin Slattery has been awarded the J B Kearney Cup by the Irish Cruising Club (ICC).

The J. B Kearney is awarded to individuals for their outstanding contribution to Irish Sailing. The committee unanimously agreed to award Justin the trophy in recognition of his two decades of racing at the highest level, including five Volvo ocean races and for being a leading Ambassador to the Irish sailing community.

It will be presented to him at the annual dinner of the ICC in Howth YC on February 19.

Well deserved Juddy - the man I never go to see without! @adorlog #goazzam https://t.co/PhThliIyvt

— Ian Walker (@ADORSkipper) December 10, 2015

Restored 1897 Belfast Lough OD Tern Makes Successful Debut At Les Voiles De St Tropez 2015

The 1897-built Fife-designed 37ft Belfast Lough One Design Tern has made a successful debut in the classics scene in the Mediterranean by winning her class in Les Voiles de St Tropez 2015 writes W M Nixon.

We’ve reported from time to time on the Mallorca-based restoration project on Tern on Afloat.ie over the past 18 months. But we were keeping our fingers crossed that all would continue to go well after her successful launching on August 6th - so much effort was going into the final work and detailed finishing that, with time limited before she could be taken to the major regattas in the south of France, all and any sorts of hitches could still occur.

Since then, there has been further concern with the weather in southeast France being exceptionally bad, with seriously adverse effects in recent days on the classic events in both Cannes and St Tropez. But Tern has not only come through unscathed, she has won her class overall despite the fact that there was only racing on two days at St Tropez, recording a first and second.

This has all been hugely confidence-building for the team involved, and greatly improves the likelihood of Tern coming to Ireland next year. The Royal Ulster Yacht Club on Belfast Lough – which was her home club in her early days and still displays several photos of Tern and her six pioneering sisters from 1897 and 1898 - is celebrating its 150th Anniversary in 2016, while at different times Tern was also based in Cork Harbour, Waterford and Dun Laoghaire, and she was one of the five yachts taking part in the Founding Cruise of the Irish Cruising Club to Glengarriff in July 1929, giving Tern direct links with all of the Irish coast between West Cork and County Antrim, as she was built by Hilditch in Carrickfergus.

Aboard Tern on her first sail since restoration, off the coast of Mallorca in August

When the new Belfast Lough ODs started racing in May 1897, it all happened so quickly that when sailmakers Ratsey & Lapthorne at their Scottish loft found that they lacked Tern’s allocated sail number 7, shortage of time meant they simply used an inverted 2 instead, and this has been faithfully replicated in the new 2015 sails, also made by Ratsey & Lapthorne.

When the new Belfast Lough ODs started racing in May 1897, it all happened so quickly that when sailmakers Ratsey & Lapthorne at their Scottish loft found that they lacked Tern’s allocated sail number 7, shortage of time meant they simply used an inverted 2 instead, and this has been faithfully replicated in the new 2015 sails, also made by Ratsey & Lapthorne.

As well, the hull lines of the BLOD 25s from 1897 were then used for the building of the Dublin Bay 25s from 1898 onwards, though the Dublin Bay boats had a higher specification, and carried a lead ballast keel instead of the Belfast Lough boats’ less expensive cast iron.

One of the famous William Maguire Dublin Bay models in the National Yacht Club is of the Fife-designed Dublin Bay 25ft OD, whose hull lines were identical to Tern. And Tern herself - though by that time rigged as a cruising yawl - was based at the National YC from 1944 to 1954, firstly under the joint ownership of Charles E Hogg and Maurice Healy from 1944 to 1949, and then under the ownership of J J Lenihan until 1954, after which she moved to Falmouth in southwest England. Photo: W M Nixon

Why Shouldn't The Irish Be A Seafaring People?

We may be an island nation, but are we a maritime people in our outlook and way of life? It could be reasonably argued that we most definitely aren’t. On last night’s Seascapes, the maritime programme on RTE Radio 1, Afloat.ie’s W M Nixon put forward a theory as to why this should be so. It’s based on a premise so simple that you’d be very confident somebody else must have pointed it out a long time ago. Yet despite Nixon’s notion being in the realms of the bleeding obvious, even with the aid of Google we cannot find any other commentator or historian making a straightforward suggestion along these lines, but will gladly welcome proof to the contrary.

Why aren’t we Irish one of the world’s great seafaring people? After all, we live on one of the most clearly defined islands on the planet. And it’s an island which is strategically located on international sea trading routes, set in the midst of a potentially fish-rich sea. Our coastline, meanwhile, is well blessed with natural havens, many of which are in turn conveniently connected to our hinterland by fine rivers which, in any truly boat-minded society, would naturally form an integrated national waterborne transport system.

Yet the traditional perception of us is as farmers, cattle traders and horse breeders of world standard, while the more modern view would include our growing expertise in information technology and an undoubted talent for high-powered activity in the international aviation industry. Then too, there is our long-established standing in the world of letters and communication and the media generally. Yet although there are now encouraging signs of a healthier attitude towards seafaring and maritime matters, particularly in the Cork region, for most Irish people the thought of a career in the global seafaring and marine industry simply doesn’t come up for consideration at all.

So why is this the case? I think the basic answer could not be simpler. The fact is, nobody ever walked to Ireland. The prehistoric land-bridges to Britain had disappeared before any human habitation occurred here. Our earliest settlers could only have arrived by primitive boat, and that was only ten thousand or so years ago. But even then, boats were still so basic that the often horrific seafaring experiences would have generated the pious hope of having absolutely nothing further to do with the sea and seafaring for the passengers, once they’d got safely ashore. And that attitude was handed down from one generation to the next.

While the south of England, with its land-bridge still connected to continental Europe, had experienced quite advanced human habitations for maybe as long as 400,000 years, Ireland by contrast was one of the very last places in the temperate zones to be taken over by human settlement, and those first settlers must have come by boat of some sort.

So even in terms of the relatively brief period of human existence on Earth, the settlement of Ireland is only the blink of an eye. Thus in talking of “Old Ireland”, we’re talking nonsense. Ireland is a very new place in terms of its human history. Yet although we’ve only been here ten thousand years, all the archaeological research points to the relatively rapid development of a complex society with some very impressive monuments being built in a relatively short period, and by a society which had become highly organised and technologically advanced within a compact timespan. Newgrange in County Meath - 5000 years old, and eloquent evidence of the sophistication of Ireland of the time

Newgrange in County Meath - 5000 years old, and eloquent evidence of the sophistication of Ireland of the time

Newgrange’s location close to the River Boyne (top right) is a reminder that while basic river transport had become quite highly developed, in this era Irish seafaring was still in its earliest and most primitive stages despite the people’s ability to undertake the advanced calculations used in the construction of Newgrange.

So these were not a people who were just passing through. The earliest Irish were determined to make something special of their new home with some colossal and impressive sacred buildings and structures. To some extent this reflected the possibility that they were totally committed to creating a meaningful life in Ireland perhaps because they saw themselves as now marooned on it.

This sense of being marooned would have become embedded and emphasised in the compact family and tribal groups which very slowly spread across the island as a basic farming and hunting people. The inherited memories of the horror of the voyage to attempt to reach Ireland, in which many lives must have been lost at sea, would have been passed down from generation to generation, and we can be sure that the potential hazards of such an enterprise would lose nothing in the re-telling and embellishment of the ancient stories around the family hearth.

In other words, the longer your people have been in Ireland, then the greater would be your inherited sense of the risk in seafaring. Put another way, you could say that the very earliest Irish were not a seafaring people because the very earliest Irish mammies were absolutely determined that their sons were not going to seek a living on the dreadful sea. In the way of Irish mammies, they made sure that everyone knew this, and they have continued to do so to the present day.

If this emphasis on the adverse effect of inherited unhappy memories seems to over-state the case, consider the circumstances of the ancient people of the Canary Islands. When the Spanish voyagers first discovered the Canaries at a time not so very distant from Columbus’s voyages to America, they thought initially that the islands were uninhabited. It was only later that it was discovered that the highest mountain regions were home to an isolated people who were distantly related to the Berbers of North Africa.

In the remote past, these mountain people’s ancestors had somehow – possibly unintentionally – made the 62 mile voyage across from Africa. It is only eight miles further than the shortest distance between Wales and Ireland. But the seas are significantly warmer, which you’d expect to be a favourable circumstance for encouraging further voyaging. Yet having finally struggled ashore, those first Canary Islanders were very soon distancing themselves from the sea and seafaring.

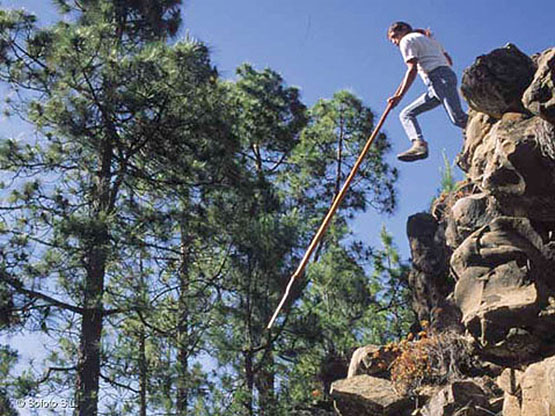

The Shepherd’s Leap (Salto del Pastor) of the Canary Islands. The earliest islanders in the Canaries turned their backs on boats and the sea so completely that they retreated away from the coasts and went to live in the mountains. There, they developed a unique way of life including this primitive pole-vaulting – now a traditional sport – in order to descend cliffs or traverse ravines

The Shepherd’s Leap (Salto del Pastor) of the Canary Islands. The earliest islanders in the Canaries turned their backs on boats and the sea so completely that they retreated away from the coasts and went to live in the mountains. There, they developed a unique way of life including this primitive pole-vaulting – now a traditional sport – in order to descend cliffs or traverse ravines

Any small enthusiasm they might have had for boats soon disappeared completely, such that they now have no shared knowledge or memory of boats at all. And up in the mountains, their most remarkable talent is the ability to pole vault down into or across the ravines – the Shepherd’s Leap - in order to travel about in their vertiginous homeland, which was seen as preferable in every way to the real dangers of seafaring.

In a Thomas Davis lecture for Seascapes a dozen or so years ago, I discussed the specialised nature of those whose primary interest in the early days of Irish settlement lay in seeing seafaring as a viable way of life. So relatively rare were such people that I reckoned at the time that this talent for exploiting the diverse wealth which the sea offered would provide them with useful survival mechanism for themselves and future generations of their families.

But I now realise that I got it totally wrong. Absolutely the opposite must have been the case. Once you and your people had got safely to Ireland in the first wave of settlers, the seafaring was still so basic and consistently dangerous that having nothing further to do with it was a much better way of ensuring the continuing survival of your genetic stock, whereas producing a family of would-be sailors could see the end of the line in a very short few years.

Although the popular view in Ireland is that our earliest ancestors must have sailed direct from Iberia, it seems to me that Western European seafaring would have been so primitive in those days ten thousand years ago that the first settlers must have voyaged across in nondescript vessels from the most easily reached part of the nearby British land, which is the large island of Islay off southwest Scotland.

As it happens, DNA testing on the current population of southwest Scotland indicates that they too have significant elements of our Iberian stock. Thus there is a shared gene pool, and the earliest Irish most likely came by the easiest route from Scotland, whose people in turn had travelled overland from Europe via England.

If that seems a bit hard to take for those of us who like to think that we’re essentially a Mediterranean people left out in the rain, that we’re essentially a formerly seafaring race who came directly by sea from our ancestral homelands in the Basque region, be consoled by the fact that many centuries later Scotland itself was to undergo conquest by invaders from Ireland of the Scoti tribe, who gave a new name to a country formerly dominated by the Picts.

However, that was very much later, when seafaring technology had greatly advanced, and people could regularly sail across the waters between Ireland and Scotland with some confidence. But when the earliest land-starved pioneers were contemplating crossing to Ireland from Scotland, they would have first looked for the shortest route. The absolute shortest distances between Scotland and northeast Ireland is in the North Channel between the Mull of Kintyre and Fair Head in County Antrim. There, the straight line distance is barely a dozen miles, yet you are facing one of the most tide-riven, roughest and coldest sea channels in Europe. And should you make it safely across, the landing at the nearest point on either side is decidedly difficult.

Further south, the shortest distance between the Mull of Galloway in southwest Scotland across the North Channel to northeast County Down is only 20 miles, but here again in early times the landings were inhospitable on either side, and the tides could be ferocious in their adverse impact.

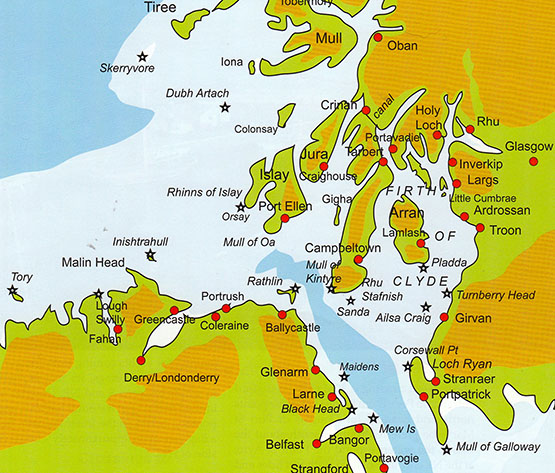

The crossings between Scotland and northeast Ireland which would have been faced by the earliest settlers. While the shortest distance between Kintyre and Fair Head to the east of Ballycastle is just over 12 miles, and the distance between Portpatrick and the nearest part of County Down is barely twenty miles, the entire North Channel between Rathlin Island and the Mull of Galloway is tide-riven, notoriously rough, and with the coldest sea temperatures on the Irish Coast. The earliest voyagers in very primtive boats would thus have had a better chance of a safe crossing, with more options as to their ultimate landfall, by setting off from Port Ellen in Islay, and having avoided the notorious tide race to the southwest of the Mull of Oa, then shaped their course to wherever the winds suited to make a landfall between Inishtrahull and Rathlin. The oldest human settlement in Ireland is at Mount Sandel near Coleraine. Plan courtesy Irish Cruising Club

But if you approached the Scotland-Ireland passage from the mainland of Scotland to the northeast, gradually working your way southwestwards through the southern Hebrides and gaining some seafaring experience with short inter-island hops until you were strategically placed at the natural harbour of what is now Port Ellen on the south shore of Islay, then the prospects were better. You might have still been all of 25 miles from Ireland, but it was a more manageable crossing. You had much greater choice in your possible destinations in making an Irish landfall, as you’d the entire Irish coast from Fair Head to Malin Head to aim for.

In reasonable weather, you could see where you were going, and with prevailing westerly winds there’d be a good chance it would be a relatively easy beam reach if you happened to have a primitive sailing rig, though the likelihood is the early boats were paddled, or rowed in primitive style.

Whatever the method of propulsion, there’s no disputing that one of the oldest sites of human habitation in Ireland is right in the middle of this northern coastline, at Mount Sandel on the River Bann in Coleraine. Yet no matter how much research and archaeology has been undertaken at Mount Sandel and at other ancient sites, no evidence of significant Irish human settlement has been found which goes back any further than ten thousand years.

As it happens, it was ten thousand years ago that mankind first developed the genetic mutation that enabled our ancestors to digest dairy products. But another five thousand years were to elapse before the first cattle were brought to Ireland to find that the place might have been invented for them, and cattle became a source and a measure of wealth. This new socioeconomic development pushed the sea and any form of seafaring even further down the social scale as a viable career option. Who would think of being a fulltime sea fisherman in a land noted as flowing in milk and honey? And even though water transport using rivers became a significant part of Irish life – notably in Fermanagh where the Maguires were to have a water-based mini-Kingdom - the sea was still viewed with suspicion, while the consumption of fish – whether from salt water or fresh – was regarded as socially inferior to eating meat.

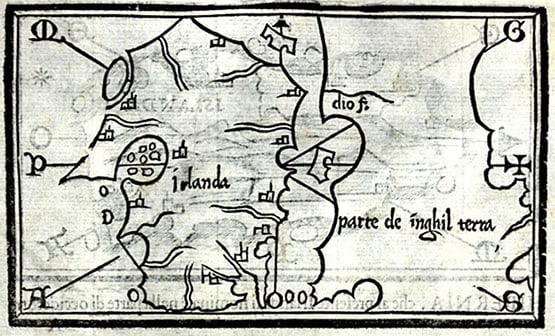

Mediaeval map of Ireland. It’s just possible that the island-studded inlet shown on the west coast is the Maguire-ruled Lough Erne, but more likely it is Clew Bay given prominence through Grace O’Malley.

It was only with improvements in seafaring technology and the general seaworthiness of ships that later generations and new groups of settlers might have brought a more positive attitude towards the sea. Then there was a period of about 1200 years – rudely ended by the first arrival of the Vikings around 795AD – when Ireland was remarkably free of invasions, yet enough marine technology had developed in the island for a brief flowering of Irish seafaring with the extraordinary voyaging of the Irish monks.

It has been argued by some scholars that there was no such person as St Brendan the Navigator. But undoubtedly there were great seafaring monks, and those of us who say that if it wasn’t St Brendan then it was somebody else of the same name will occasionally make the pilgrimage across from Dingle to rugged little Brendan Creek close under the west slopes of Mount Brandon on the north shore of the Dingle Peninsula, and wonder again at those Irish men of limitless faith setting out from this sacred spot into the great unknown in light but able boats.

But as it was seaborne asceticism which they sought rather than wealth, it was seen as a highly specialized and rather odd interest when most of the people were much more readily drawn to epic tales of profitable cattle raiding.

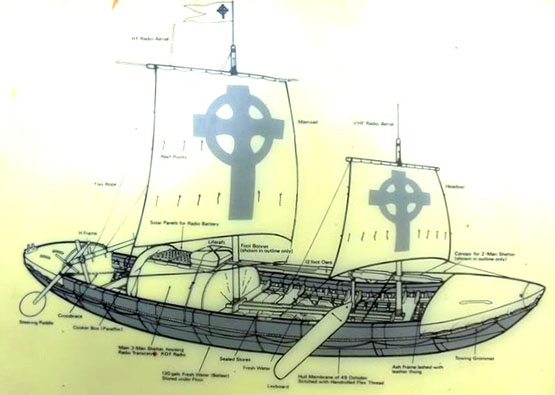

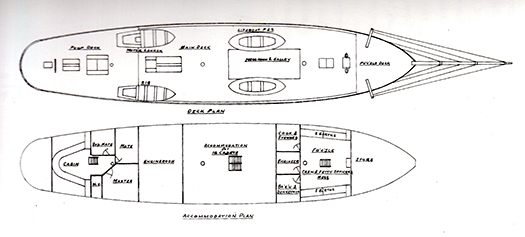

Details of Tim Severin’s oxhide “giant currach” with which – in 1976-77 - he showed that the supposedly mythical Transatlantic voyages of St Brendan the Navigator were technically possible. The St Brendan - which with Denis Doyle’s encouragement was built in Crosshaven Boatyard in 1975-76 – is now on permanent display at Craggaunowen in County Clare.

Then came the Vikings. Say what you like about the Vikings - and everybody has an opinion – but the reality is that their longships represented a quantum leap in naval architecture development. They brought state-of-the-art voyaging in versatile ships way ahead of anything seen before. Yet in time the Vikings were in their turn sucked into the Irish way of doing things, and far from turning Ireland into a seafaring nation, they seem to have literally burned their boats and set up home ashore, gradually absorbing the negative attitude towards the sea of their new neighbours, and taking on board the inevitable anti-seafaring attitudes of their new mothers-in-law

It wasn’t immediately as simple as that, of course. For a while, Ireland was the focal point of the Vikings’ sea trading routes along the coasts of western Europe, while Dublin had the doubtful distinction of being the biggest slave market in the constantly changing Viking western empire, which wasn’t really a territorial empire in the traditional sense, but was more a sphere of active influence and commercial and raiding activity. But it was undoubtedly a major centre which was totally dominated by all Viking activities, including ship-building, and the return to Dublin in 2006 of the 100ft Sea Stallion of Glendalough, a re-creation of one of the biggest Viking ships ever built (in Dublin in 1042), was a telling reminder of just how much Dublin had been to the fore in Viking life, while this video is a timely reminder of the great project completed in Roskilde ten years ago.

Inevitably, people of Viking descent were becoming a significant element in the Irish population, and even today we would naturally expect someone called Doyle to have something of the sea in their veins. Yet the Irish capacity for absorption of newcomers into the old ways of thinking has worked here too. The most common Irish surname today is Murphy. It means sea warrior. While those of us with maritime interests in mind would like to think it referred to an ancient tribe who went forth from Ireland to do successful battle on distant seas, we know in our heart of hearts that the Murphys are descended from warriors – mostly Vikings - who came in from the sea.

In time, they were enticed into domesticity by comely maidens who in due course became the formidable Irish mammies who prohibited any seafaring by their sons. Indeed, so far are most Murphys removed today from the sea that in some parts of the world the name is still a patronising nickname for the potato, something which is useful enough in its way, but its only maritime link is through fish and chips.

After the Vikings and then the Normans – who were really only Vikings with some slightly less rough French manners put on them – subsequent invasions were English-dominated, and the growth of British sea power was done in a manner which made sure that any Irish role in it was strictly of a subservient nature.

Rockfleet Castle in County Mayo, reputed deathplace of Grace O’Malley in June 1603. She was everything she shouldn’t have been, and in heroic style. She was Irish yet a mighty seafarer in command of her own ships, and a woman, yet a ruthless ruler of power and wealth who could combat men on equal terms.

Of course there were local heroes who tried to oppose this, the most renowned being Grace O’Malley, the Sea Queen of Connacht. But even when people of English descent tried to establish a separate Irish seafaring identity, as happened with the merchants of Drogheda, their aspirations would be slapped down by the dominant power and control from the government in London and the influence of the merchants of Bristol.

However, the government only had to look the other way for a moment before there was some local maritime enterprise was trying to flourish, and in the late 18th and early 19th Century the North Dublin smugglers, privateers and pirates of the little port of Rush in Fingal, people like Luke Ryan and James Mathews, were pace-setters in Europe and across the Atlantic, striking deals with Benjamin Franklin among others.

Depending on the state of international hostilities, sometimes their privateering trade could be quite open, and in Dublin the Freeman’s Journal of 23rd February 1779 reported that “we find the little fishing village of Rush has already fitted out four vessels, and one of them is now in Dublin at Rogerson’s Quay, ready to sail, being completely armed and manned, carrying 14 carriage guns and 60 of as brave hands as any in Europe”.

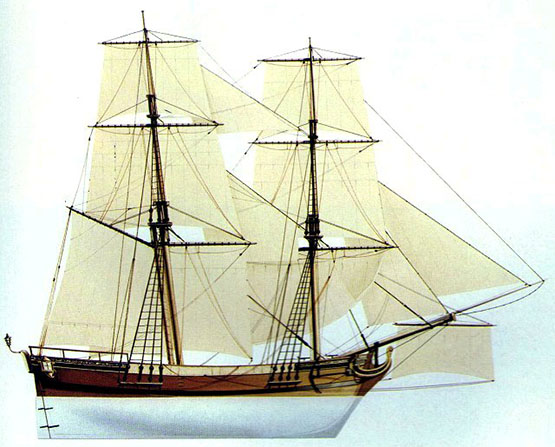

A late 19th century privateer, built for speed. When times were good for privateering, the little port of Rush in Fingal could provide a flotilla of these craft, which at other times could be kept hidden in the Rogerstown Estuary

The Admiral from Mayo. Being press-ganged by the Royal Navy was one of the many career-changing events which resulted in William Brown from Foxford becoming the founder-Admiral of the Argentine Navy.

But the majority of Irish seafarers were employed only in the humblest roles afloat, and often through the activities of the shore-raiding involuntary recruitment drives of the press gangs of Britain’s Royal Navy, However, this could produce some wonderful examples of unexpected consequences. The most complex was William Brown, of Foxford in Mayo, who had somehow risen to be a Captain in the American merchant marine when he was press-ganged into the Royal Navy, and after many vicissitudes, he ended up as a merchant in Buenos Aires. There, thanks to his unexpected acquisition of experience in naval warfare by courtesy of the Royal Navy, he became the founder of the Argentine Navy and an Admiral, as one does…..

Then there was the 18th Century Patrick Lynch of Galway, …….according to some stories, he was press-ganged. Be that as it may, the family made their fortune eventually in South America and a descendant, Patricio Lynch, owned the ship Heroina which played a significant role in Argentine history. The family continued to prosper in many directions, such that one decendant was Che Guevara, while another is the yacht designer German Frers, whose own pet yacht (which he gets little enough opportunity to use, as he is so busy designing boats for others) is called Heriona in honour of the family’s complex historic links through the sea with Ireland.

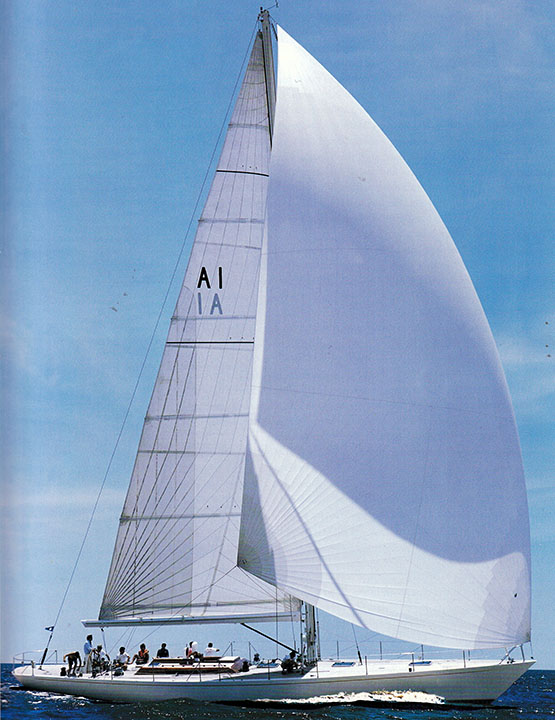

Yacht designer German Frers sailing his personal 74ft sloop Heroina in the River Plate. The boat is named in honour of the historic ship which belonged to his ancestor Patricio Lynch.

But while a very few of the young Irishmen press-ganged by the Royal Navy may ultimately have prospered in unexpected ways, the vast majority most definitely didn’t. Most came to a horrible end, while those who had managed to escape the press gangs’ clutches, together with the rest of the bulk of the native population, were reinforced in their inherited distrust of seafaring in any form.

Thus although we may now feel pride in the fact that the world’s first recreational sailing club was established with the Water Club of the Harbour of Cork in 1720, it’s difficult to avoid the conclusion that those great Munster landowners and merchants who founded it were partly doing it subconsciously just to show how very different they were from the ordinary run of Irish people in their attitude to the sea.

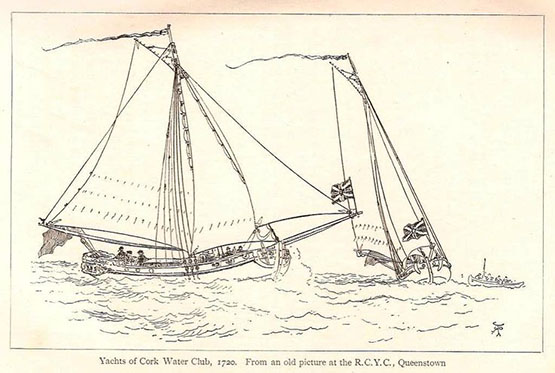

First instance of the “have nots” and the “have yachts”? The establishment of the Water Club of the Harbour of Cork in 1720 was a remarkable achievement, but if anything it emphasised the fact that the vast majority of Irish people had no enthusiasm or capability for the sea. Courtesy RCYC.

As for the official attitude when the Irish Free State finally came into being, its was so painfully sea-blind that we still need to draw a veil over its attitude, only noting that the first significant voyage under the new Irish ensign was made by one of that much-maligned class, a yachtsman. This was the great venture round the world south of the capes by Conor O’Brien of Limerick with his little Baltimore-built Saoirse between 1923 and 1925.

Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse departs Dun Laoghaire on her world- girding voyage on 20th June 1923.

O’Brien was to find Ireland so stultifying in its outlook after his return that he sailed away to live elsewhere, and we have to accept that for several decades the official approach reinforced the notion that being interested in the sea is un-Irish. So if we hope to change this attitude which still lingers today, a useful first step is to accept that for many of us, being non-maritime is the most natural thing in the world – we’ve had it instinctively from the very beginning, it’s in our handed-down and repeatedly-instilled inherited memories from the time when our most distant ancestors struggled ashore from battered little boats somewhere on the north coast, knowing that many others had died, and would die, trying to do the same thing.

Far from trying to pretend that this attitude doesn’t really exist, surely a much better way is to accept that it does, but that we’ve researched a perfectly valid explanation as to why this is so. Thus the way forward for Ireland to fulfill her maritime potential is to realize why this attitude is there in us, and take mature steps to offset it.

The fact is, in dealing with the sea, the Irish people have never had a level playing field. We’ve had to live with it and our inherited memories of being on it in very adverse circumstances. Unlike continental land dwellers, we have had no choice in the matter - we don’t see the sea as somewhere excitingly new with endless possibilities, we see it only with inherited distrust. And the determination of the current wave of walking migrants from the Middle East into Europe to attempt the sea crossing at only the narrowest part is further dreadful evidence of this.

But in another area of human endeavour, we’ve shown that we can do the business in competition with other nations. When aviation began to become part of everyday life a hundred years ago, it was unknown territory for all mankind. In terms of getting to grips with flying, it was a level playing field for all.

Yet here we are now in Ireland, an island in the Atlantic which is playing an extraordinarily active and central role in many aspects of aviation management and development, and certainly punching way above our weight. Looking at what we have been able to do in the air, it is surely time to look again at what we might do with the sea if we can look at it from a fresh perspective, and adapt the same can-do energies of the Irish aviation industry to the business of seafaring.

It’s time and more to shake off the old fears of the sea, while always maintaining a healthy respect for its undoubted power. That is best done by being in the vanguard of maritime technological development. And down around Cork Harbour, they’re doing that very thing. It’s just possible that, despite our ingrained anti-maritime attitude, we are beginning to view the sea in a more healthy and positive way. And it’s from our great southern port that we’re beginning to get inspiring leadership as the sea beckons us towards fresh opportunities.

So what, if nobody ever walked to Ireland? So what, if our distant ancestors had a very cold, very wet and very rough time getting here? It’s time to move on. Time to get over it. Time to start seeing the sea in a sensible way.

The little ship that carried the maritime hopes of a new nation. Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse in dry dock, showing the tough little hull that was able to register a good mileage most days in the Southern Ocean while still sailing in comfort. Yet when he returned to Dun Laoghaire in 1925 to complete his voyage with a rapturous homecoming reception, Conor O’Brien was soon to find that beneath the welcome there was increasing official indifference in the new Free State to Ireland’s maritime potential.

#maritimesafety – The Minister for Transport, Tourism and Sport, Paschal Donohoe, TD, today launched a new Maritime Safety Strategy 2015 – 2019, the theme of which is 'Make Time for Maritime Safety.'

The new Strategy was developed following a consultation with key stakeholders and the general public and includes an analysis of the factors contributing to maritime fatalities in Ireland.

A link to the Maritime Safety Strategy document is HERE.

"My Department's maritime safety remit covers safety on recreational craft, including surfboards, fishing vessels and cargo ships and it is these areas which are covered by the Strategy we are launching today. Although the average annual number of marine incident-related fatalities, at 11, is low, lives continue to be lost on the water, despite regulation, inspections and training. Perhaps not surprisingly, most incidents happen in the fishing and recreational sectors. What is striking, however, is the fact that 99% of maritime fatalities are male, with an average age of 44, and that fatalities in the maritime sector are potentially avoidable.

"There is broad agreement in the sector that to reduce fatalities, the focus needs to be on changing culture and personal behaviour rather than on more regulation. While this Strategy primarily identifies actions that the Department, through the Irish Maritime Administration (IMA) will take, the important roles of individuals, families, friends and sectoral organisations are also highlighted.

"Notwithstanding the efforts of my Department in terms of preventative action, enforcement and emergency response, these efforts cannot on their own improve maritime safety. It is up to each individual who takes to the water to take personal responsibility for their actions and to understand that failure to operate safely puts not just their own life at risk, but the lives of others on board and potentially the lives of emergency and rescue personnel.

"The genesis of this Strategy was the emergence of recurring causal factors in marine casualty investigation reports and recognition of the extent to which maritime fatalities and incidents could be avoided. Among the top 10 factors identified from analysis of the Marine Casualty Investigation Board (MCIB) reports are:

· The need for an enhanced maritime safety culture

· Unsuitable or inadequately maintained safety equipment on board, or lack thereof

· Lack of crew training

· Failure to plan journeys safely, including failure to take sea/weather conditions into account

· Non-wearing of personal flotation device (lifejacket/buoyancy aid)

· Vessel unseaworthy, unstable and/or overloaded

"The 33 actions outlined in the report are grouped under five over-arching strategic objectives; Information and Communication, Search and Rescue Operations, Standards, Enforcement, Data and Evaluation. They are centred on promoting personal responsibility for maritime safety, improving search and rescue, and implementing preventative measures, including a robust inspection and regulatory framework, and an enhanced enforcement regime. They are designed, in a holistic way, to tackle the factors contributing to maritime fatalities and to ultimately reduce in the number of lives lost in the maritime sector.

"This strategy sets out in a very straightforward way, what individuals, families, friends and communities can do to ensure safety when taking to the water. This includes proper planning, operating on a safety first basis, always telling somebody where you are going and when you expect to be back, wearing suitable clothing and always wearing lifejackets and buoyance aids. The Strategy concludes by outlining what my Department can and will do to support a better maritime safety culture. I urge everyone involved in the sector to pay close heed to the Strategy's contents so that together we can reduce, and eventually eliminate, needless fatalities at sea."

#WaterSafety - The Government's 'Sea Change' consultation contained sobering statistics on boating fatalities in Irish waters, prompting calls for much tighter water safety regulation. But as Irish Cruising Club spokesman and Sailing Directions Editor Norman Kean writes, that view is not shared by all in the marine sector...

In June 2014, the Department of Transport issued a consultation document titled 'Sea Change', in which it was alleged that over an 11-year period, 66 fatalities had occurred on recreational craft. This represents 47% of all marine fatalities in the period, and the figure was widely and sometimes sensationally reported.

In light of that, it's worth examining the following extracts from the Irish Cruising Club's (ICC) submission to the department, which reflects an independent study of the original Marine Casualty Investigation Board (MCIB) reports:

The MCIB reports for the period 2002 to 2012 describe 42 incidents involving craft other than licensed commercial or fishing vessels. Presumably these are classified, by default, as leisure-related. These 42 incidents resulted in 51 deaths. We believe it is significant and worthwhile to note that 28 of these fatalities (55%) occurred when the purpose was not recreational boating per se. Twenty-two people lost their lives while out fishing, five while ferrying or as passengers, and one on a hunting trip by boat. The remaining 23 comprised eight kayakers/canoeists, three jet-skiers, five sailing and seven power-boating, each activity in these 23 cases being carried out for its own sake.

There is circumstantial evidence to suggest that of the 22 'recreational' fishing casualties, at least 10 may have actually been out for commercial purposes. The same applies to at least two of the 'ferrying' category. We have knowledgeable independent support for that view.

Sixteen casualties, including the eight kayakers, lost their lives in rivers or lakes, and 35 in tidal water.

Sixteen of the 51 deaths occurred between November and April, not a time of year normally associated with recreational boating.

Most incidents involved small open boats; all but five vessels were under seven metres in length. One of those five was a 7.3-metre undecked gleoiteog.

Perhaps the most telling statistic is that in 32 cases, lifejackets were inaccessible, faulty or badly adjusted, or not worn when they clearly should have been. This, and much else described in the MCIB reports, indicate a disturbing recklessness and lack of awareness on the part of the casualties and their companions.

The discrepancy between the figure of 51 deaths investigated by the MCIB and 66 quoted in the consultation document presumably reflects the inclusion of diving, surfing and sailboarding casualties as 'recreational craft' accidents. These do not fall within the remit of the MCIB, for a good reason: diving is a specialised skill, and accidents seldom if ever have anything to do with the operation or actions of the boat; while a surfboard is not a boat.

The submission also goes on to say that "almost every one of the [nine contributory causes listed in the consultation document] is in turn a result of the above-mentioned lack of awareness, and... if that lack could be adequately addressed, many issues like 'failure to plan journeys safely' and 'vessel unseaworthy, unstable and/or overloaded' would simply no longer arise. This is the commonplace observation of every skilled and experienced recreational sailor; we see it all the time."

Our point was – of course - that the representation of recreational sailing as being particularly hazardous was a grossly unfair interpretation of the statistics.

The ICC was the only yacht club in Ireland to respond (the ISA also sent in a submission) and the RNLI was the only other organisation not to take the department's figures at face value. There were 36 submissions in total, many of them from professional organisations such as the Harbourmasters, the Irish Lights, the Naval Service, the Irish Coast Guard and the Institute of Master Mariners. Almost without exception these bodies and individuals wanted leisure craft and their crews to be highly regulated, sometimes to an utterly draconian extent.

In general, none of their recommendations would have the slightest effect on accident rates or consequences unless implemented with a zeal worthy of the Taliban. What they would undoubtedly do is make life easier and less stressful for the watch officer on the bridge of a ship or in the coastguard station, which one can well understand.

It is worthy of note that the RNLI and Irish Water Safety shared our view that education was preferable to regulation.

Sailing's Secret Side Revealed in Irish Cruising Club Awards

#irishcruisingawards – As the recent Irish Sailing Association's Public Consultation meetings in Dun Laoghaire, Cork and Galway to discuss its new Strategic Plan 2015-2020 have shown, the cruising community may not be high profile, but there are many of them, and their behavioural patterns in going afloat, and ways and means of doing it, are as varied as their extraordinary range of boats.

What is clearly emerging is that the cruising people expect Irish sailing's national authority to be able to guide them towards qualifying for the International Certificate of Competence, it also expects them to be able to negotiate the government into a more sensible and manageable system of boat registration, and it expects the ISA to be up to speed on the problems being faced about the lack of convenient fuel pumps for marine diesel, and the continuing confusion in the situation regarding which type of fuel is legally available for use on boats.

But while those who cruise expect the ISA to provide a user-friendly administrative environment in which they can go about their various projects and pleasures afloat provided that they comply with statutory safety regulations, they do not seem to wish the ISA to be organisationally involved with what they actually do afloat. W M Nixon takes up the story.

Racing, with its global structure of competition, its many internationally-recognised rules and regulations, and its basic requirements of competence by event management teams, is an obvious area of interest for the Irish Sailing Association through supportive action and, where required, direct involvement.

But cruising......well, for the racing obsessives who garner the bulk of sailing's attention and publicity despite probably being the minority of those who go afloat, cruising is usually seen simply as "not racing". It is essentially a private venture usually involving just one boat and her crew. And even where experienced crews have committed themselves to taking part in a more formalized Cruise-in-Company run by some group or club, they expect significant segments of down-time where each boat or small groups of buddy boats can go off and do their own sweet thing in terms of itinerary and length of passage chosen.

But for most cruising crews, the ideal cruise is carefully planned for just one boat, taking into account the time available and the capabilities of boat and crew, and making due allowance for the conditions prevailing in the cruising ground selected, while always realizing that the final word on what is or is not achieved will be ultimately dictated by the weather.

On such cruises, while some arrangements may be made ahead, with crew changing at pre-ordained ports often a dominant factor, the underlying hope is that there will be a sense of freedom of movement as to specific ports and anchorages being visited. And far from expecting to cruise in a formalized group, the traditional cruising enthusiast will reckon that new friends met informally ashore or on other boats in newly-visited anchorages and harbours is all an essential part of the colourful mix of unplanned yet enjoyable experiences which makes up a good cruise for just one boat voyaging on her own.

Objective achieved. Eddie Nicholson's Najad 440 Mollihawk's Shadow from Kinsale in the midst of things in the far northern harbour of Illulissat in West Greenland. This was the cruise which has been awarded the ICC's Strangford Cup. Photo: Pat Dorgan

Then too, every so often the boat and her crew will have to deal with adverse weather conditions. Doing so successfully and competently is part of a truly satisfying cruise. And so is reaching some objective, whether it be a distant port or island, or some place which provides access to a desirable mountain top to meet the needs of those climbers who are drawn to the possibilities offered by a cruising boat's wide range of destination options.

And then there are the cherished memories which only cruising can provide, while equally there are shoreside experiences which seem heightened when you've come off a boat to witness them. For instance, the famous swing of the mighty incense-filled Botafumeiro in the ancient cathedral at Santiago de Compostela in Galicia in northwest Spain is something wonderful to behold at any time, but when you happen upon it by lucky chance the day after you've sailed your boat out to Spain from Ireland, it becomes almost supernatural.

As for experiences which are exclusive to cruising folk, you can only really sail in to Venice with the dawn on a cruising boat, the only way to see Bonifacio as Ulysses saw it is when cruising, only with a cruising boat can you coast along under the absurdly vertical and ridiculously high Fuglabjorgs – the bird cliffs – of the Faeroes, only when you've got there with a cruising boat can you really savour the unique sense of place at Village Bay in St Kilda, and only by arriving in a lone cruising boat can you grasp just what a very special place is to be found at Inishbofin.

So who needs a picture frame? Mollihawk's Shadow in a classic Greenland setting. Photo Pat Dorgan

While the unique pleasures of cruising are available to anyone with the basic experience and ability combined with access to an appropriate boat whether owned or chartered, in the final analysis these are private pleasure, intensely personal in their meaning. And thus they're just about unmeasurable by any known system. So how on earth can any national authority which is inevitably training and racing oriented get a handle on what is going on in the world of Irish cruising?

Well, you could try just counting the number of boats with a lid in each port which don't go racing, and simply conclude that they should be added to statistics as part of the Irish cruising fleet. You could go into more detail by research through questionnaires to marina berth or mooring holders. And you could extrapolate answers which might give some sort of statistical picture. But as the recent Sports Council report on the numbers supposedly taking part in all areas of watersports involving floating vehicles of some sort or other and based on figures supplied by each special interest organization might suggest, you could well end up with some rather fanciful totals.

Thus last night's Annual General Meeting in Dun Laoghaire of the Irish Cruising Club was more than just a get-together of the organisation which has been at the heart of Irish cruising from its formation in 1929. For the ICC AGM is when Irish cruising is most closely analyzing itself. Since its formation, the club has become firmly established in its central role through publishing its unrivalled sailing directions for the entire coast of Ireland in two regularly up-dated volumes based on unrivalled local knowledge.

Man at work. ICC Sailing Directions Hon. Editor Norman Kean has placed Niall Quinn's new Ovni 395 Aircin in a decidedly neat little spot in Bellacragher Bay on the mainland side of Achill Sound during a research of the neighbourhood. For his tireless efforts on behalf of pilotage research, Norman Kean has been awarded the Rockabil Trophy for 2014. Photo: Norman Kean

But while the Sailing Directions are the public face of the ICC, there's a more private face which last night also went public with the presentation of the club's annual cruising awards. While cruising is indeed an ephemeral activity which can be difficult to measure and analyse in any meaningful way, cruising awards are specific trophies for the best cruise in some particular category.

While they were viewed with suspicion in the early days of cruising, the fact is that the keeping of a seamanlike log has always been a central part of proper seafaring, and these days its translation into a manageable narrative, eligible for a cruising award, is regarded as an integral part of the sport (and here we use "sport" in that special Irish sense to describe an activity which is not necessarily directly competitive, but has a certain edge of fun to it, for in active cruising you're in competition with yourself).

And of course a proper log also provides – or should provide - useful information for those who may be planning to visit the same cruising ground. But it's in the bigger picture that a well-prepared log is at its most useful, as it assists those trying to grasp just what Irish cruising is all about, and how it is developing.

The superb collection of logs compiled by Honorary Editor Ed Wheeler in the Irish Cruising Club Annual 2014 is a fact-filled picture of Irish cruising as it is today, so perhaps it should be required reading for those members of the Board of the ISA who don't really get what cruising is all about.

That said, there are those who would point out that if you don't "get" proper cruising after experiencing just a little bit of it, then you'll never get it, and there's little point in trying to grasp its multiple meanings. If that's the case, then please just accept that it is there, it's an important part of the Irish sailing scene, and those of us who cherish it simply wish to be left in peace to get on with it with a minimum of bureaucratic interference.

But enough already of trying to set the scene. With 33 full logs of cruises in many areas with widely varying mileages, and in boats of all sizes from the 70ft schooner Spirit of Oysterhaven (Oliver Hart) down to the 24ft gaff cutter North Star cruised by Mick Delap of Valentia Island, the Irish Cruising Club Annual 2014 further augments its plethora of information and entertainment with eleven additional mini-logs, and Honorary Editor Ed Wheeler is to be congratulated on putting together such an eclectic collection in a way that makes sense and gives us an unrivalled overview of contemporary Irish cruising.

Also worthy of congratulation and indeed commiseration is Log Adjudicator Arthur Baker of Cork, for with such an abundance of voyages, the fact that the Club's eleven challenge awards are generally very specific in their categories meant that he had a formidable array of cruises to choose from for the two premier Trophies, the Faulkner Cup for the best cruise of the year which dates back to 1931, and the Strangford Cup which was inaugurated in 1970 for "an alternative best cruise", as by 1970 too many very meritorious cruises were not getting the recognition they deserved.cru5.jpg

Cruising partners. Neil Hegarty and Ann Kenny in the Caribbean during Shelduck's award-winning cruise. When they're not cruising his Dufour 34, they're cruising her Chance 37 Tam O'Shanter which is currently in the Baltic.

When you're told it's called the Dismal Swamp Canal, you've just got to go and see it. Neil Hegarty on Shelduck's wheel as she departs North Carolina via the Dismal Swamp Canal. Photo: Ann Kenny

FAULKNER CUP for best cruise in 2014.

Neil Hegarty (Crosshaven) with Shelduck, a 2003 Dufour 34. Shelduck's eight month cruise started with an east-west Transatlantic crossing, and then continued through the Caribbean including Cuba and on in detail up the East Coast of America until, after transitting the cheerfully-named Dismal Swamp Canal, they laid up for the hurricane season in the Atlantic Yacht Basin just north of Cape Hatteras. While other crews were aboard occasionally, throughout the voyage Neil Hegarty (a retired architect who was formerly in the forefront of racing fleets) was crewed by Ann Kenny of Tralee, whose own boat, the Chance 37 Tam O'Shanter, is currently in the Baltic. So to balance the Atlantic experience, they then went on for three weeks of Baltic cruising in the perfect sailing weather which that great inland sea enjoyed for much of 2014.

STRANGFORD CUP for alternative best cruise.

Eddie Nicholson, who sails from Kinsale, has been cruising the American side of the Atlantic in considerable detail since 2008 with his 2007 Najad 440 Mollihawk's Shadow. The boat's name derives from the 70ft 1903-built schooner Mollihawk with which a relative, Commander Vernon Nicholson of Cork and his family, sailed across the Atlantic in 1948. Their intention had been to get to Australia, but in cruising the Caribbean en route they sailed in to the abandoned and deserted former Royal Navy port of English Harbour on Antigua. They'd barely settled in the anchorage when some guests from a nearby hotel found their way on board and asked to be taken for a sail. Thus was Nicholson Yacht Charters brought into being. Any Australian plan was soon abandoned, and Antigua as we know it today, the focus of Caribbean sailing and home to the RORC Caribbean 600, was showing its first signs of its new existence in the winter of 1947-48 thanks to the arrival of Mollihawk.

A long way indeed from the balmy breezes of Antigua where the schooner Mollyhawk made her new home in 1948. These are classic Greenland conditions as seen from Mollyhawk's Shadow during 2014, Photo: Pat Dorgan

Her near namesake has been spending recent summers in waters remote from the balmy delights of the Caribbean, as she has been up and around eastern Canada. In 2014 Eddie and his number one shipmate Pat Dorgan combined forces to bring the much-travelled boat home via Greenland where, on the West Coast, they got as far north as Illulisat which looks to be a perfectly charming spot, but it still contrived in mid-summer to have its entrance blocked by ice from time to time. In fact, this was a cruise to West Greenland which started in Newfoundland and concluded in Kinsale, and when you work out what all that means, then you're beginning to grasp the sheer diversity of contemporary Irish Cruising Club activity.

THE ATLANTIC TROPHY is for the best cruise with an ocean passage of at least a thousand miles, and it goes to John Coyne of Galway for a nicely-balanced cruise with Lir, his 1990 van de Stadt 10.4m steel sloop. Lir's voyage took her from Galway Bay south to northwest Spain, then across to the Azores, then home to Ireland to sail 1,219 miles from Ponta Delgada to Inishbofin, which is Atlantic cruising at its very best.

John Coyne's Lir sailing on her home waters of Galway Bay. In 2014 she sailed first to Northwest Spain, then to the Azores and thence to Inishbofin.

THE ROCKABILL TROPHY is for exceptional seamanship or navigation, and adjudicator Arthur Baker very cleverly turned it into a sort of Lifetime Achievement Award for Norman Kean of Courtmacsherry, who is of course the ever-diligent Honorary Editor of the Irish Cruising Club Sailing Directions, and in 2014 he was to be found on board various members' boats in some distinctly obscure locations, pushing the envelope for tiny anchorages.

THE FINGAL TROPHY goes to any log with a certain quirkiness which appeals to the judge, and for 2014 it is for Ian Stevenson and Frances McArthur's account of the early-season cruise of the 1994 Beneteau First 42s7 Raptor from Strangford Lough to northwest Spain for much port-hopping, then back across Biscay to cruise South Brittany in considerable detail, then home to Strangford – 2124 miles in all.

THE WILD GOOSE CUP, presented by the late Wallace Clark whose writings on cruising were universally admired, is for a log of literary merit. Theoretically it could be won by a cruise of just a hundred miles, but for 2014 it is the stylishly recounted story of the 2800 miles sailed by the Tony Castro-designed CS 40 Hecuba from her home port of Cascais in Portugal down to the Canaries, thence to the Azores, then back to Portugal, which most deservedly sees John Duggan awarded the trophy.

THE MARIE TROPHY - best cruise by a boat less than 30ft.

The little 1894-built cutter Marie was the first boat to be awarded the Faulkner Cup in 1931, and this trophy celebrating her memory is a reminder that the ICC is for boats of all sizes. With his part-owned Moody 27 Mystic, Peter Fernie of Galway fits well within the upper size limit for this award, yet with a crew of very senior sailors he'd himself a fine old time cruising from GBSC at Rinville to Kinsale and back, visiting all the best ports and anchorages in between.

THE GLENGARRIFF TROPHY is for the best cruise in Irish waters. Curiously enough, while there may have been boats which got round Ireland as part of other ventures, there was no specifically round Ireland cruise to be eligible for the ICC's Round Ireland Cup, which dates back to 1954. But the newer Glengarriff Trophy has a wider brief, and it goes to Brendan O'Callaghan of Kinsale for a cruise from Dun Laoghaire northabout to Rossaveal in Galway Bay in the Westerly Fumar 32 Katlin, with many of those unplanned yet hugely entertaining meetings along the way with other cruising boats, which is what true cruising is all about.

THE PERRY GREER BOWL is for the best first log by a new member. They seldom get as good as this, as Justin McDonagh of Killarney's debut account of his family cruise with the 2010 alloy-built van de Stadt 12m sloop Selkie takes us from the Canaries to the Caribbean, thence to Maine via Bermuda, and finally to New York, a wonderful achievement by any standards.

THE FORTNIGHT CUP is for the best cruise within 16 days.

In 2010, 2011 and 2012, Fergus and Kay Quinlan of Kinvara with their own-built van de Stadt steel cutter Pylades were awarded the Faulkner Cup three years on the trot as their fascinating voyage around the world rolled on. But in 2014 they showed they could cut the mustard when time was limited. Pylades headed north from Galway Bay and by the time they returned they'd been to islands as various as Tory, Barra, Eriskay, Canna, Mull, Colonsay, and Inishturk.

THE WYBRANTS CUP is for the best cruise in Scottsh waters, which may seem an odd trophy for an Irish club, but the ICC has a significant membership in the north, and the west of Scotland is their Southwest Ireland. For 2014 the Wybrants Cup goes to Matthew Wright who cruised the Sweden 38 Thor from Bangor far north along the Scottish mainland's west coast, but also found time for a detailed visit to Skye including the remarkable Loch Scavaig.

The Irish Cruising Club has several other trophies for specific achievements, and one of the most poignant moments of 2014 came in December when the ICC's JOHN B KEARNEY CUP for services to sailing was posthumously awarded to the much-mourned Joe English.

Last night, another trophy for special service and achievement went to Kieran Jameson of Howth, who received the DONEGAN MEMORIAL TROPHY for years of devotion to offshore sailing in a career which includes 15 consecutive Fastnet Races, nine consecutive Round Ireland Races, one Middle Sea Race, one Round Britain and Ireland Race, and one ARC.

Northern ICC member and environmental activist Brian Black was also honoured with the WRIGHT SALVER for his remarkable series of voyages far north along the challenging East Coast of Greenland - he got to72N in 2014.

A steel-built gaff yawl? The 44ft Young Larry is unique in many ways, and now her owners Andrew and Maire Wilkes have been awarded the very special Fastnet Trophy

Another special award which has found a new home is the ICC's FASTNET TROPHY, which is not necessarily presented every year, and is for exceptional international achievement in any maritime sphere. The latest recipients are Andrew Wilkes of Lymington in England and Maire Breathnath of Dungarvan. They've been Mr & Mrs Wilkes for some time now, but their achievements are such that they deserve to be recognised as two remarkable individuals whose extensive cruising in the 44ft steel-built gaff yawl Young Larry is simply astonishing, as it has included a complete circuit of North America which took them through the Northwest Passage some years ago when it was still a prodigious challenge. During 2014 they took the opportunity to cruise in detail to many of the places between west Greenland and eastern Canada which they'd had to hasten past before, and awarding the Fastnet Trophy to them is proper recognition of a level of dedication to cruising which few of us can even begin to imagine.

Of course, not all ICC activity is to utterly rugged places, and one of 2014's more intriguing ventures was by Paddy Barry (no stranger to distant icy places himself) with his alloy-built former racer, the Frers 45 Ar Seachrain. He provided the mother-ship for a waterborne camino to Santiago de Compostella being made by the Kerry naomhog Niamh Gobnait, led by the legendary Danny Sheehy. This traditional 24ft craft has already been rowed round Ireland and up to Iona, and by the end of 2014's stage of the voyage to northest Spain, they'd got to Douarnenez in Brittany with the Biscay crossing in prospect for this summer.

Although the 24ft Kerry naomhog has been rowed round Ireland and up to Iona, the current voyage to Santiago is in another league. This year Danny Sheehy and his team plan to get to the other side of the Bay of Biscay from their current winter storage in Douarnenez. Photo: Patricia Moriarty

Altogether less serious but a date well worth celebrating was the 85th Anniversary of the foundation of the Irish Cruising Club at Glengarriff on the 13th July 1929. So Paddy McGlade of Cork organised an easygoing cruise in company for 35 boats in which the only totally rigid date was being in Glengarriff for July 13th, which was duly achieved. And prominent in the fleet was ICC member Oliver Hart's 70ft schooner Spirit of Oysterhaven. This is a boat which has to work for her living as a sail training vessel. But the ICC were able to take this comfortably in their stride, as the continuing steady sale of the voluntarily-produced Sailing Directions leaves the club with a modest financial surplus. In 2014, some of this was re-directed to provide eight bursaries so that young people could avail of Sail Training opportunities on Spirit of Oysterhaven during the Cruise-in-Company, an imaginative use of funds which worked very well indeed.

Part of the ICC fleet in Glengarriff for the 85th Anniversary. The smallest boat, Mick Delap's 24ft North Star, is on the right. Photo: Barbara Love

The biggest boat in the fleet – Oliver Hart's 70ft schooner Spirit of Oysterhaven was carrying a crew of trainees as part of the Cruise-in-Company

A New Tall Ship For Ireland? It's Back to The Future

#tallship – The Tall Ships return to Ireland in spectacular style this summer with a major fleet assembly in Belfast from Thursday 2nd to Sunday 5th July for the beginning of the season's Tall Ships Races, organised by Sail Training International. The seagoing programme will have a strong Scandinavian emphasis in 2015, with the route - some of which is racing, other sections at your own speed – starting from Belfast to go on Aalesund in western Norway for 16th to 18th July, thence to Kristiansand (25th to 28th July), which is immediately east of Norway's south point, and then on to conclude at Aalborg in northern Denmark from 1st to 4th August.

But before leaving Northern Ireland with the potentially very spectacular Parade of Sail down Belfast Lough on Sunday July 5th, the celebrations will be mighty. The fleet's visit will be the central part of the Lidl Belfast Titanic Maritime Festival, which will include everything from popular family fun happenings with concerts and fireworks displays – the full works, in other words – right up to high–powered corporate entertainment attractions.

As for the ships, there will be more than enough for any traditional rig and tall ship enthusiast to spend a week drooling over. In all, as many as eighty vessels of all sizes are expected. But more importantly, at least twenty of them will be serious Tall Ships, proper Class A square riggers of at least 40 metres in length, which is double the number which took part in their last visit to Belfast, back in 2009.

That smaller fleet of six years ago seemed decidedly spectacular to most of us at the time. So the vision of a doubling of proper Tall Ship numbers in Belfast Harbour is something we can only begin to imagine. But when you've a fleet which will include Class A ships of the calibre of the new Alexander von Humboldt from Germany, Norway's two beauties Christian Radich and Sorlandet, the much-loved Europa from the Netherlands, George Stage from Denmark, and the extraordinary Shtandart from Russia which is a re-creation of an 18th Century vessel built for Emperor Peter the Great, you're only starting, as that's to name only six vessels – what we'll be seeing will be a truly rare gathering of the crème de la creme.

So although it would be stretching it to think that a small country like Ireland should aspire to having a major full-rigged vessel, we mustn't forget that for 27 glorious years we did have our own much-admired miniature Tall Ship, the gallant 84–ft brigantine Asgard II. Six-and-a-half years years after her loss, it's time and more for her to be replaced. W M Nixon takes a look at what's been going on behind the scenes in the world of sail training in Ireland and finds that, in the end, we may find ourselves with a ship which will look very like a concept first aired for Irish sail training way back in 1954.

The pain of it. You search out a photo of Shtandart, the remarkable Russian re-creation of an 18th century ship, and you find that Asgard II is sailing beside her

It was while sourcing a photo of Russia's unusual sail training ship Shtandart that the pain of the loss of Asgard II emerged again. It's always there, just below the surface. But it's usually kept in place by the thought that we have to move on, that worse things happened during the grim years of Ireland plunging ever deeper into recession, and that while our beloved ship did indeed sink, no lives were loss and her abandonment was carried out in an exercise of exemplary seamanship.

Yet up came the photo of the Shtandard, and there right beside her was Asgard II, sailing merrily along on what's probably the Baltic, and flying the flag for Ireland with her usual grace and charm. The pain of seeing her doing what she did best really was intense. She is much mourned by everyone who knew her, and particularly those who crewed aboard her. All three of my sons sailed on her as trainees, they all had themselves a great time, and two of them enjoyed it so much they repeated the experience and both became Watch Leaders. It was very gratifying to find afterwards, when you went out into the big wide world and put "Watch Leader Asgard II" on your CV, that it counted for something significant in international seafaring terms.

But as a sailing family with other boat options to fall back on, we didn't feel Asgard II's loss nearly as acutely as those country folk for whom the ship provided the only access to the exciting new world of life on the high seas.

Elaine Byrne vividly recalls how much she appreciated sailing on Asgard II, and how she and her siblings, growing up in the depths of rural Ireland, came to regard the experience of sailing as a trainee on the ship as a "Rite of Passage" through young adulthood

The noted international investigative researcher, academic and journalist Dr Elaine Byrne is from the Carlow/Wicklow border, the oldest of seven children in a farming family where the household income is augmented with a funeral undertaking business attached to a pub in which she still occasionally works. Thus her background is just about as far as it's possible to be from Ireland's limited maritime community. Yet thanks to Asgard II, she was able to take a step into the unknown world of the high seas as a trainee on board, and liked it so much that over the years she spent two months in all aboard Asgard II, graduating through the Watch Leader scheme and sailing in the Tall Ships programmes of races and cruises-in-company

Down in the depths of the country, her new experiences changed the Byrne family's perceptions of seafaring. Elaine Byrne writes:

"Four of my siblings (then) had the opportunity to sail on Asgard II. If it were not for Asgard II, my family would never have had the chance to sail, as we did not live near the sea, nor had the financial resources to do so. The Asgard II played a large role in our family life as it became a Rite of Passage to sail on board her. My two youngest siblings did not sail on the Asgard II because she sank, which they much regret".

She continues: "Apart from the discipline of sailing and the adventure of new experiences and countries, the Asgard brought people of different social class and background together. There are few experiences which can achieve so much during the formative years of young adulthood"

That's it from the heart – and from the heart of the country too, from l'Irlande profonde. So, as the economy starts to pick up again, when you've heard the real meaning of Asgard II expressed so directly then it's time to expect some proper tall ship action for Ireland in the near future. But it's not going to be a simple business. So maybe we should take quick canter through the convoluted story of how Asgard II came into being, in the realization that in its way, creating her successor is proving to be every bit as complex.

As we shall see, the story actually goes back earlier, but we'll begin in 1961 when Erskine Childers's historic 1905-built 51ft ketch Asgard was bought and brought back by the Irish government under some effective public pressure. It was assumed that a vessel of this size – quite a large yacht by the Irish standards of the time – would make an ideal sail training vessel and floating ambassador. It was equally assumed that the Naval Service would be happy to run her. But apart from keen sailing enthusiasts in the Naval Reserve - people like Lt Buddy Thompson and Lt Sean Flood – the Naval Service had enough on its plate with restricted budgets and ageing ships for their primary purpose of fishery patrol.

Aboard the first Asgard in 1961 during her brief period in the 1960s as a sail training vessel with the Naval Service – Lt Sean Flood is at the helm

So Asgard was increasingly neglected throughout the 1960s until Charlie Haughey, the new Minister for Finance and the only member of Government with the slightest interest in the sea, was persuaded by the sailing community that Asgard could become a viable sail training ship. In 1968 she was removed from the remit of the Department for Defence into the hands of some rather bewildered officials in the Department for Finance, and a voluntary committee of five experienced sailing people - Coiste an Asgard - was set up to oversee her conversion for sail training use in the boatyard at Malahide, which just happened to be rather less than a million miles from the Minister's constituency.

Asgard in her full sail training role in 1970 in Dublin Bay

Asgard was commissioned in her new role in Howth, the scene of her historic gun running in 1914, in the spring of 1969. Under the dedicated command of Captain Eric Healy, the little ship did her very best, but it soon became obvious that her days of active use would be limited by reasons of age, and anyway she was too small to be used for the important sail training vessel roles of providing space to entertain local bigwigs and decision-makers in blazers.

By 1972, the need for a replacement vessel was a matter of growing debate in the sailing community, and during a cruise in West Cork in the summer of 1972, I got talking to Dermot Kennedy of Baltimore out on Cape Clear. Dermot was the man who introduced Glenans to Ireland in 1969, and then he branched out on his own in sail training schools. A man of firm opinions, he reacted with derision to my suggestion that Asgard's replacement should be a modern glassfibre Bermudan ketch, but with enough sails to keep half a dozen trainees busy.

"Nonsense" snorted Dermot. "Ireland needs a real sailing ship, a miniature tall ship maybe, but still a real ship, big enough to carry square rig and have a proper clipper bow and capture the imagination and pride of every Irish person who sets eyes on her. And she should be painted dark green just to show she's the Irish sail training ship, and no doubt about it".

Some time that winter I simply mentioned his suggestions in Afloat magazine, and during the Christmas holidays they were read by Jack Tyrrell at his home in Arklow. During his boyhood, in the school holidays he had sailed with his uncle on the Arklow schooner Lady of Avenel, and it had so shaped his development into the man who was capable of running Ireland's most successful boatyard that he had long dreamed of a modern version of the Lady of Avenel to be Ireland's sail training ship.

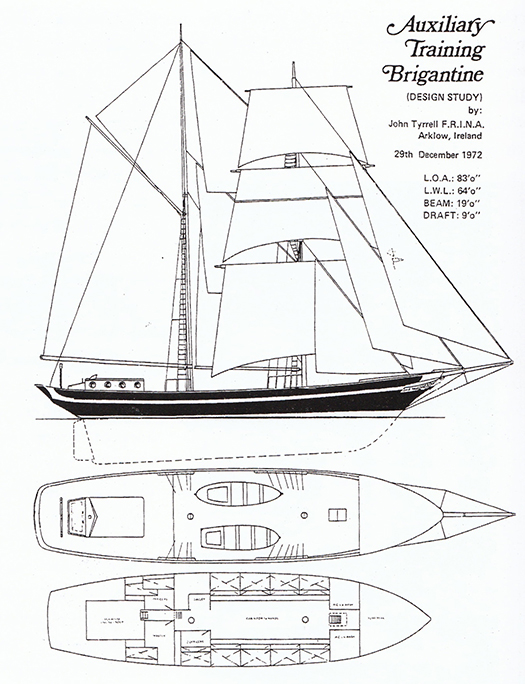

The inspiration – Jack Tyrrell's boyhood experiences aboard Lady of Avenel inspired him to create Ireland's first proper sail training ship