Displaying items by tag: Ireland's Eye

Ireland’s Eye Snapped Up By Investment Group

Howth’s iconic Ireland’s Eye has been purchased by investment group Tetrarch Capital, TheJournal.ie comfirms.

The island — which is an important breeding spot for many seabirds — was included in the recent sale of Howth Castle and demesne by the Gaisford-St Lawrence family, whose ancestors held the lands since the 12th century Norman invasion.

The new owners say visitors are still “very welcome to the island” and boat trips will continue to be offered by local operators.

“It is our intention to work closely with key stakeholders to preserve the beauty, amenity and accessibility of Ireland’s Eye,” a spokesperson for Tetrarch Capital said.

Tetrarch Capital’s portfolio includes Kilkenny’s Mount Juliet Estate, hotels at Citywest and Powerscourt, and a number of development sites in Dublin city centre.

Planning Hearing On Clonshaugh Wastewater Plant Gets Under Way

Planners are from today set to review proposals for a controversial €500 million wastewater treatment scheme in North Dublin, as The Irish Times reports.

Clonshaugh near Dublin Airport was chosen in June 2013 as the site for the sewage ‘super plant’ before Irish Water took over the Greater Dublin Drainage project from Fingal County Council last year.

The new plant — second only to the Ringsend wastewater facility in scope — would be connected to a new orbital sewer to Blanchardstown, and an outfall pipe to eject treated wastewater in the sea north of Ireland’s Eye.

Plans for the new sewage processing plant have faced strong local opposition, both from residents adjacent to the Clonshaugh site and connected works and marine professionals concerned about potential environmental risks.

Last October, Howth-based ferryman Ken Doyle expressed his fears of the knock-on effect on fish stocks from any accidental contamination of the local waters from the outfall pipe.

The planning hearing began at The Gresham hotel in Dublin this morning, and The Irish Times has more on the story HERE.

#MarineWildlife - A Howth-based ferryman fears for marine wildlife on and around Ireland’s Eye when a planned sewage outfall pipe begins discharging wastewater in the area.

Ken Doyle of Ireland’s Eye Ferries tells Dublin Live that any accidental contamination of the waters from the pipeline, from Clonshaugh to a mile off the small island immediately north of Howth, could have a disastrous knock-on effect on fish stocks — an issue both for sea anglers and local bird and seal colonies.

Five years ago, Clonshaugh in North Co Dublin was chosen as the location for the capital’s wastewater treatment ‘super plant’.

The scheme will connect a 26km orbital sewer through counties Dublin, Kildare and Meath with an outfall pipeline ejecting waste off Ireland’s Eye.

Doyle noted that when the outflow of raw sewage at Howth Head was ended with the opening of the Ringsend treatment plant, improvements in water quality meant “the bird population increased hugely and it’s all positive but I wouldn’t like it to go back to like it was.”

He adds that he is not opposed to the wastewater scheme in principle — only that he and other local residents and businesses want assurances that the plant will not have any negative impact on the environment.

Bid to Rid Ireland’s Eye of a Build-up of Marine Litter

Seastainability and Clean Coasts coordinated a specialised clean-up of Ireland’s Eye off the fishing village of Howth, Co. Dublin. Ken of Ireland’s Eye Ferries offered his support by ferrying 23 volunteers to the island to undertake the mass clean up.

It is estimated that half a tonne of marine litter was removed from the Island. The volunteers were not only locals, but many came from the greater Dublin area. David Hughes gave the group a brief history of the Island on landing and Tara Adcock of Birdwatch Ireland enlightened the group of the many types of seabirds dwelling on the Island.

Seastainability Founder, Rebecca Flanagan said; Looking out at this beautiful, uninhabited Island every day, you would never imagine the level of litter and marine debris matted into the sand and rock. It’s an interesting area to survey since the level of foot fall is relatively low compared to Howth Village. No one group is responsible for cleaning or preserving Ireland’s Eye so the level of debris we found on our pre-assessment was alarming. This Island is a habitat for Seabirds and Seals, yet sadly it has become a landing area for wandering marine litter and fishing equipment.

"23 volunteers trekked 70 bags of debris across the Island"

The volunteers cleared an accumulation of plastic litter, lengths of tangled fishing ropes, fishing material, textiles, aluminium cans and glass. 23 volunteers trekked 70 bags of debris across the Island where it was loaded onto two ferry boats and brought back to Howth Harbour.

Ireland’s Eye Ferry owner, Ken Doyle commented; Ireland's Eye Ferries were delighted to facilitate the volunteers from Seastainability and Clean Coasts. Ireland's Eye is a beautiful amenity so close to the city and keeping it clean is in the best interests of all who use it, wildlife and human. Well done to all for their efforts today. We will continue to encourage all visitors to take their rubbish home with them.

Clean Coasts Coastal Programme Officer, Richard Curtin said; Clean Coasts were delighted to be involved with this clean-up of Ireland’s Eye which is one of the most beautiful sites on the Dublin Coastline. The volunteers braved the wet conditions and did trojan work to remove such a large quantity of rubbish. Each year millions of tonnes of marine litter enter our seas and oceans, resulting in environmental, economic, health and aesthetic challenges. Clean-ups such as this help in reversing these trends.

A great sense of community and collaboration was felt by all involved. The Beshoffs Market Cafe, welcomed the volunteers to the West Pier with a rewarding hot drink refreshment and newly appointed Harbour Master, Harry McLoughlin, arranged the disposal of the collected debris.

Dublin Bay Sailing Partnership Based on Artistic Endeavour

#iris – It has been said that keeping a boat-owning partnership intact is much more difficult than maintaining a marriage in a healthy state. Thus for most of us with the boat-owning vocation, sole ownership is the only way to go. But for others, in order to defray costs, increase boat size, and maybe leave more personal time free to pursue other interests, the ambitions can best be realised through one of a wide variety of partnerships and syndicates.

These can go through an extensive range, starting at one extreme with what amounts to time-sharing, with the large number of owners meeting (if they meet at all) only once a year for a sort of Annual General Meeting. Other possible setups can mutate through various arrangements where there is considerable overlap between the boat uses by the different owners, right through to the other extreme of total partnership where all owners sail together as often as is possible.

In some cases, the additional social glue of special shared interests is needed to give the partnership that essential extra vitality. There's nothing new in this. W M Nixon takes a look back a hundred years and more to a boat-owning group whose shared interest in art kept a 60ft ketch on a regular cruising programme around Dublin Bay and the nearby coastlines.

The 60ft gaff ketch Iris had a chequered career. She started life at the peak of the Victorian era in the 19th Century as a naval pinnace serving Dublin Bay, and she was presumably driven by steam. At the time, Dun Laoghaire – then known as Kingstown – was becoming the height of fashion as a naval port of call in the summer, made even more so by its convenient access to the centres of power in Dublin, and its strategically useful direct rail connection – pierhead to pierhead – to the main Royal Navy base in Ireland at Cobh on Cork Harbour.

However, as Kingstown had initially been planned solely as a harbour of refuge – an asylum harbor - for ships in distress in onshore gales, with the actual spur to its construction (starting in 1817) being the wrecking of a British troopship with huge loss of life at Seapoint on the south shore of Dublin Bay, the plans had included no provision for convenient alongside berthing for ships.

Indeed, you get the impression that the original underlying thinking was that there should be as little social contact as possible between ships sheltering in the new harbour and any inhabitants of its nearby undeveloped shore. But the rapid if somewhat chaotic growth of the makings of a new harbourside town, plus the advent of more rapid access from Dublin with the coming of the railway in 1834, soon meant that the top brass expected to be able to get off and on their ships in the harbour in style and comfort, and their Lordships of the Admiralty did not stint in providing large pinnaces for them to do so. When these pinnaces were replaced in due course by even more luxurious vessels, those shrewd amateur sailors who could visualise the older boats' potential as re-cycled government surplus found themselves looking at a bargain.

The Iris was originally built with lifeboat-style construction of double-diagonal hardwood planking, which was quite advanced technology for the time. For the can-do boatbuilders of the late 19th Century, converting such totally purpose-built craft into some sort of a yacht was all part of a day's work. Another similarly-built if smaller and different-shaped vessel, Erskine Childers' Vixen on which the Dulcibella of The Riddle of the Sands fame was based, was formerly an RNLI lifeboat with the standard lifeboat canoe stern. She was made more yacht-like by the addition of a staging aft to compensate for the absence of deck space just where you most need it, while underneath this new permanent staging, additional supporting planking was faired into the hull and – hey presto – you've a yacht-like counter stern.

Vixen also had a massive centre-plate complete with its huge casing, and carried more than three tons of internal iron ballast, all of which left little enough space for living aboard during the long and often rough cruise through the Friesian Islands which provided much of the on-the-ground material – and we can mean that in every sense – on which The Riddle was based.

Erskine Childers' Vixen (on which "Dulcibella of The Riddle" was based) in one of his last seasons of ownership in 1899. At first glance, she looks like a typical old-style cruising cutter of her era. But somewhere in there is a classic canoe-sterned RNLI lifeboat hull to which an afterdeck on a counter stern have been fitted as an add-on.

That cruise was in 1897, and shortly after it was completed, Childers went off to serve in the Boer War. This experience left him with doubts about the validity of the British Imperial mission, but equally left him in no doubt that on active service, there were no medals for enduring unnecessary discomfort. So by the time The Riddle of the Sands was published in 1903, Vixen was sold and he'd become a partner in a much more comfortable cruising boat, the yawl Sunbeam, which in turn was followed in 1905 by his very comfortable dreamship Asgard

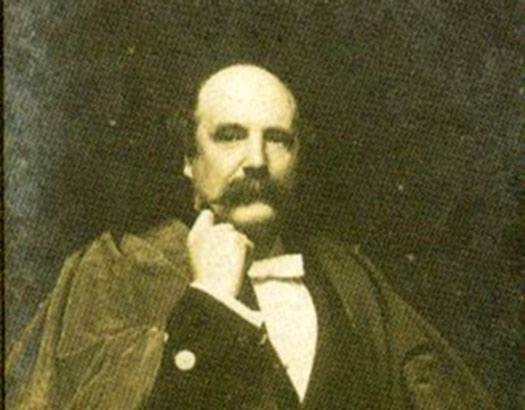

Meanwhile, with the Iris a fifteen or so years earlier in Dublin, the conversion to a comfortable sailing cruiser was a more straightforward affair, as she'd a more versatile hull shape with a broad stern in the first place, and her new owner was one George Prescott, an innovator bordering on genius. He was an optical and scientific instrument maker, an electrical engineer and inventor, and a state-of-the-art clockmaker.

Man of many parts – the polymath George Prescott. Organising the Graphic Cruising Club and running its club-ship Iris was only one of his many interests. He led a long and extraordinarily interesting and varied life, and was nearly a hundred years old at the time of his death in 1942. Courtesy Cormac Lowth

But that was only one part of his life, for he had many friends among Dublin artists, particularly those interested in maritime topics, and he soon found himself to be the secretary of the Graphic Cruisers Club for sailing painters and sketchers, with the Iris becoming the base of their waterborne creative and scientific expeditions on the coast of the greater Dublin area.

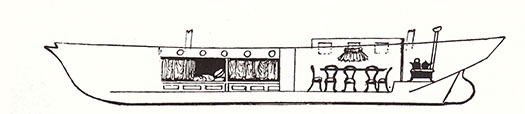

She was ideal for this. She'd been converted for sailing with an orthodox gaff ketch rig, while her roomy hull was internally re-configured to have a galley with a large stove right aft, a huge saloon immediately forward of the galley to be both the clubroom and dining room, and sleeping quarters port and starboard in pilot cutter style forward of that.

Quite a transformation for a former steam-powered naval pinnace. The 60ft ketch Irish in her heyday as the club ship of the Graphic Cruisers Club in the 1890s. She is at her home anchorage off Ringsend, while across the Liffey a couple of Ringsend trawlers are lying in the roadstead known as Halpin's Pool, where the Alexandra Basin is now located. Photo courtesy Cormac Lowth

Accommodation profile of the Iris in her days as the floating HQ of the Graphic Cruisers Club – this sketch by Alexander William first appeared in The Yachtsman magazine in 1894.

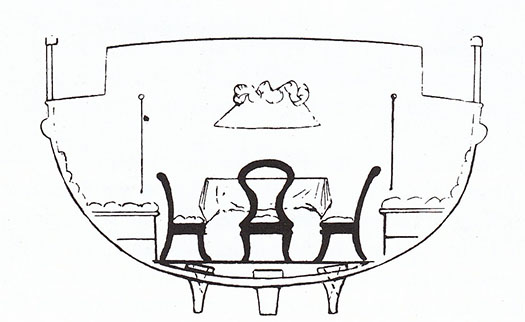

Hull section of the Iris at the saloon, showing the bilge keels which enabled her to dry out comfortably in some some little-known tidal anchorages in the Greater Dublin area.

But underneath the hull, the temptation had been resisted to add a deep keel, and instead the Iris was fitted with substantial bilge keels at the same depth as the shallow keel itself, such that in all she drew only about 3ft 6ins, and would comfortably dry out in a snug berth anywhere that her artistic crew felt they might find subjects worthy of their attention.

Thus she might overnight serenely on the beach at Ireland's Eye or far up the estuary at Rogerstown, and if the Graphic Cruisers Club attention was turned towards County Wicklow, she could comfortably take the ground in Bray or in other little ports inaccessible to orthodox cruising yachts. Yet the claim was that despite the odd arrangements beneath the waterline, she handled remarkably well on all points of sailing, and certainly as she no longer had any sort of engine, she must have sailed neatly enough to get out of some of the confined berths into which her eccentric crew enjoyed putting her.

The Iris in gentle cruising mode off Ireland's Eye as the moon rises – this was sketched by Alexander Williams for The Yachtsman in 1894.

George Prescott seems to have been happy to claim that Iris was a club-owned yacht, but in truth most of his shipmates were impecunious artists of varying talent, so it was his generosity and understated business ability which would have kept the partnership together.

However, it really did seem to function as a partnership, for after the Iris project had been up and running for nearly a decade, he turned his attention in 1896 to building an unusual house on the waterfront on the Pigeonhouse Road in Ringsend, which he happily acknowledged to be the clubhouse of the Graphic Cruisers Club even if he lived in it himself.

Called Sandefjord for some reason which is still unexplained, it looked not unlike a smaller sister of the Coastguard Station next door, complete with a lookout tower. And it's distinctly nautical within, as much of the interior includes fine panelling which came from the wrecked Finnish sailing ship Palme, with the stairs being provided by the old ship's main companionway.

The house called Sandefjord near Poolbeg Y & BC as it is in 2015. When built by George Prescott in 1896, it faced across the Pigeonhouse Road directly onto the waterfront, and overlooked the summer anchorage of the Iris. Photo: W M Nixon

The design style of the Graphic Cruisers Club shore HQ at Sandefjord reflected the lookout tower of the old Coastguard Station next door. Photo: W M Nixon

The house has been restored to become a family home in recent years, and it really is an extraordinary piece of work to come upon on the slip road down to Poolbeg Yacht & Boat Club. Meanwhile, interest in the doings of the Graphic Cruisers Club has been restored by the formidable research talents and tenacity of Cormac Lowth, who single-handedly does more work in uncovering unjustly ignored aspects of Dublin Bay's maritime life in all its variety than you'd get from an entire university department.

I first came across a reference to the Graphic Cruisers Club years ago in an article in an 1894 issue of The Yachtsman magazine, written by Alexander Williams (1846-1930), who was probably the club's most accomplished marine artist. But that was then, this is now, and it has taken Cormac Lowth's dedication in recent times to get the extraordinary setup around George Prescott and Alexander Williams and their friends and shipmates into the proper context.

Alexander Williams RHA was the best-known artist in the Graphic Cruisers Club. A taxidermist of international repute, he was also a noted ornithologist, and his interest in maritime subjects was matched by his enthusiasm for landscape. He was one of the first artists to "discover" Achill Island in the west of Ireland, and in time he created a remarkable garden there in a three years project in which he personally worked shoulder-to-shoulder with the build team.

A classic Alexander Williams portrayal of the trawlers of Ringsend with other shipping in the Liffey. Thanks to research by Cormac Lowth, we are now aware of how the style of the Ringsend sailing trawlers came about through links, between 1818 and the 1914 outbreak of Great War, with the pioneering fishing port of Brixham in Devon, which was the most technologically advanced fishing port in Europe in the mid 1800s. Courtesy Cormac Lowth

They were larger than life, every last one of them, and Prescott and Williams in particular were renaissance men who could turn their hand to any number of creative projects at a time when life around Dublin was fairly buzzing for those with the energy and interest to enjoy it.

And there were links to other aspects of Dublin waterfront life which have a further resonance. Back in January, I'd to give one of the supper talks at the National YC in Dun Laoghaire, and on this occasion the topic was John B Kearney (1879-1967), the Ringsend-born yacht designer and boatbuilder who was the club's Rear Commodore for the last 21 years of his life.

You need some sort of special little link to bring these talks to life, but fortunately I remembered that there's a fine big Alexander Williams painting of sailing trawlers at Ringsend in the NYC's dining room. I didn't know its date as we headed round the bay on the night of the talk, but we struck gold. It was dated 1890.

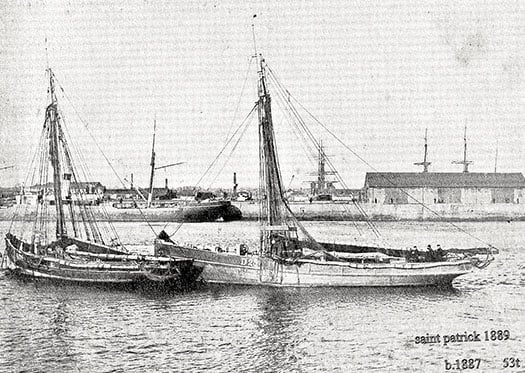

The Brixham style in Ringsend was best exemplified by the largest trawler built in the Dublin port, the St Patrick (right) of 53 tons built in 1887 in the Murphy family's boatyard beside the mouth of the River Dodder. The Murphy family also owned and operated the St Patrick in her fishing, and when John Kearney built his renowned yachts, the earliest (and best) of them were built in a corner of Murphy's Boatyard - the Ainmara in 1912, the Mavis in 1925, and the Sonia in 1929. Photo courtesy Cormac Lowth

Williams was so fond of the Ringsend scene that he lived there for a while in Thorncastle Street where John B Kearney was born, and of course the painter subsequently sailed regularly from the old port in the Iris, and would have over-nighted at Sandefjord too. He is in fact the definitive Ringsend maritime artist, and the picture in the NYC expresses this. And as it includes some of the Ringsend waterfront, we could say that it also includes John B Kearney, for in 1890 the precocious eleven-year-old Ringsend schoolboy was in the boatyards as much as possible, as he had already stated in his quietly stubborn way that his ultimate ambition was to be a yacht designer.

Not a boatbuilder or a shipwright or a harbour engineer, which is nevertheless what he was until he retired in 1944. But upon his leaving the day job - in which he'd been highly respected - he then devoted all his energies to what he had been doing all his life in his spare time. And with his death aged 88 in 1967, his gravestone in Glasnevin cemetery said it all: John Breslin Kearney (formerly of Dublin Port & Docks Board) Yacht Designer.

And if you wonder how on earth we have come to a consideration of John Kearney's memorial stone in an article which purports to be about the social glues which keep boat partnerships in good order, believe me when you get involved with the boys of the Graphic Cruisers Club you never know where it's all going to end.

We've already discovered that in later life Alexander Williams devoted much energy to his garden in Achill while at the same time continuing to be an active member of the Royal Hibernian Academy in Dublin. As for George Prescott, he too broadened his already extensive interests, and in his eighties he was much into amateur opera production, even being so deeply involved as to paint the stage scenery himself.

Dublin too was expanding, so he accepted that a move eastward was needed if he was going to be able to continue to commune directly with his beloved sea. So he left Sandefjord, and the final decades of his wonderful life were spent at his new home at The Hermitage on Merrion Strand. Needless to say, Alexander Williams provided him with a painting of The Hermitage which captured the then unspoilt nature of a place you'd scarcely recognize today.

The Hermitage on Merrion Strand, George Prescott's last home as portrayed by Alexander Williams. Courtesy Cormac Lowth

Strengthen Fingal's Freedom for the Good of Irish Sailing

#fingal – The Government's recent move to create a framework for the direct election of a new all-powerful Mayor for Dublin was expected to be a shoo-in. The new Super-Mayor's authority would incorporate the current four local councils of Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown, South Dublin, Dublin City, and Fingal, each one of which had to vote in favour. But Fingal's councillors voted firmly against it, despite emphatic support of the proposal by the councillors in the other three areas. As a Fingallion by adoption, W M Nixon strongly supports this independent move by a largely rural and coastal region which has a longer shoreline than all the other Dublin areas put together, and is clearly not a naturally integral part of the city.

Fingal is the Ukraine of Leinster, and the glowering monster of Dublin is the Russia within Ireland, intent on the conquest of its smaller freedom-seeking neighbour. Vigorous, all-powerful, intensely urban, and distinctly impressed with itself, Dublin is certain that the further its bounds are spread, the better it will be for all its citizens. And the more citizens it can claim, then the better for Dublin.

But Fingal is different. For sure, it can seem a bit sleepy and rural by comparison with central Dublin, but that's the way we like it. It's a place of odd little ports and much fishing, a region of offshore islands, rocky coasts and many beaches on one side, and the profound heart of the fertile country on the other. A place where – as you move north within it - you might make a living in many ways at once, taking in growing vegetables, raising animals, running a dairy herd, and keeping a lobster boat down at the local quay, while perhaps having a horse or two as well. And if you feel like more shore sport, the golfing options are truly world class.

As for the sailing and all other forms of recreational boating, Fingal is not just a place of remarkable variety – it's a universe. With five islands – six if you count Rockabill – its 88 kilometre coastline is one for sport, relaxation and exploration. Sea angling is well up the agenda, and it's a kayakers' paradise, while Irish speed records in sailboarding and kite-surfing have been established in the natural sand-girt canal which forms for much of the tidal cycle in the outer Baldoyle estuary immediately west of Howth.

Apart from fishing boats – and inshore they're usually only the smaller ones – it has no commercial traffic. And though there are tidal streams, in southern Fingal's main racing area between Ireland's Eye and Lambay, they're not excessively strong, and run in a reasonably clear-defined way, while the flukey winds which so often bedevil Dublin Bay away to the south are much less of a problem in sailing off Fingal, where the winds blow free.

The range of boat and sailing clubs of Fingal matches the variety of its coast. The most southerly is Sutton Dinghy Club, rare among Ireland's yacht clubs in being south-facing. It may be focused on sailing in Dublin Bay, but scratch any SDC sailor, and you'll find a Fingallion. Round the corner of the Baily – not a headland to be trifled with - Howth has two clubs, the yacht club with its own marina, and Cumann na Bhad Binn Eadair (the Howth Sailing & Boat Club) in the northeast corner of the harbour, while Howth Sea Angling Club with its large premises on the West Pier is one of the tops in the country.

The sunny south. Sutton Dinghy Club is Fingal's most southerly sailing club, and is also rare in Ireland through being south facing.

Islands of Fingal seen across the eastern part of Howth marina, with Ireland's Eye in the foreground, and Lambay beyond. Photo: W M Nixon

As for the waters they share, their most immediate neighbour is the steep island of Ireland's Eye with its pleasant southwest-facing beach, the island itself a remarkable wild nesting site, particularly when you remember that it's close beside an intensely urban setting. When a discerning visitor described Ireland's Eye as "an astonishing and perfect miniature St Kilda", he wasn't exaggerating.

Across in Malahide, where we find Fingal's other marina, Malahide YC - which recently celebrated its Golden Jubilee and currently has Graham Smith as its first second-generation Commodore – is in the curious position of having two clubhouses. One is a charming and hospitable place among trees within easy stroll of the marina, while the other is west of the long railway embankment which retains the extensive inner waters of Broadmeadow. This makes the waters into a marvellous recreational amenity and boating and sailing nursery, so not surprisingly it is home to active sailing schools. And it is also the base of Malahide YC "west", a dinghy sailing club on the Broadmeadow shore at Yellow Walls, while further west of it again is yet another club, the more recently formed Swords Sailing & Boating Club.

The map of modern Fingal shows how the southwest corner of the present region seems remote from the largely coastal and rural nature of much of the rest of the county. And it also confirms the surprise (to many) that the Phoenix Park is in Fingal.

North from Malahide, and you're into "Fingal profonde", its deeply rural nature occasionally emphasised by the sea nearby. The long Rogerstown Estuary, the next inlet after Malahide, sometimes found itself providing the northern boundary of The Pale, and as recently as the early 1800s the river at Rogerstown and the tiny port of Rush were a veritable nest of smugglers, privateers and occasionally pirates, with buccaneering captains of myth and legend such as Luke Ryan and James Mathews proving to have been real people who were pillars of society when back home in their secretive little communities after their lengthy business forays to God know where.

Muddy situation. Low water in the Rogerstown Estuary. The hill in the distance on the left is new – for years, it was the largest dump in Ireland, the Balleally Landfill. But now it is well on its way to rehabilitation as an enhancement of the landscape. Photo: W M Nixon

The Rogerstown Estuary went through an unpleasant period when its inner waters were dominated by the nearby presence of the biggest waste dump in Dublin, Balleally Landfill. It rose and rose, but now it's closed, and is in process of being revived to some sort of natural state. The result is that the vista westward from Rogerstown is much improved by a pleasant and completely new hill which so enhances the view at sunset that shrewd locals have built themselves a row of fine new houses facing west, along the quirkily named Spout Lane which runs inland from the estuary.

Whatever about the legality-pushing privateer skippers who used Rogerstown Estuary as their base in days of yore, these days it's home to the quay and storehouse which serves the ferry to Lambay, which is Fingal's only inhabited island when there are no bird wardens resident on Rockabill, and it's also the setting for another south-facing club, Rush SC. It is spiritual home these days to the historic 17ft Mermaid Class (they still occasionally build new ones in an old mill nearby), but despite the very strong tidal streams where the estuary narrows as it meets the sea, RSC also has a large cruiser fleet whose moorings are so tide-rode that unless there's a boat on the buoy, it tends to disappear under water in the final urge of the flood. This can make things distinctly interesting for strangers arriving in and hoping to borrow a mooring while avoiding getting fouled in those moorings already submerged. Not surprisingly, with their boat sizes becoming larger like everywhere else, Rush SC find that their bigger cruisers use Malahide Marina.

To seaward of Rogerstown, with the little port of Rush just round the corner, the view is dominated by Lambay. A fine big island with is own little "miniature Dun Laoghaire" to provide a harbour on its west side, it has a notable Lutyens house set among the trees. But for many years now Lambay has been a major Nature Reserve, so landing is banned, though anchorage is available in its three or four bays provided you don't interfere with the wildlife along the shore. This makes it off bounds to kayakers who might hope for a leg stretch on land, though it's still well worth paddling round close inshore.

Racing round Lambay. Close competition between the Howth 17s Aura (left) and Pauline, which have been racing annually round Lambay since 1904. Photo: John Deane

Along the Fingal mainland coast, the next inlet after Rush is Loughshinny, a lovely natural harbour with a quay to further improve the bay's shelter. There's a very active little fishing fleet, while the shoreside architecture is, how shall we say, decidedly eclectic and individualistic? Go there and you'll see what I mean.

Six miles offshore, Rockabill marks the northeast limits of Fingal. It's a fine big double-rock, with a substantial lighthouse and characterful keepers' houses attached. But as it's now automated, the only time Rockabill is inhabited is for the four summer months when a bird warden or two take up residence to monitor the rocky island's most distinguished summer residents, Europe's largest breeding colony of roseate terns.

Rockabill, where the shy roseate terns feel at home. Photo: W M Nixon

In Fingal we tend to take these pretty but noisy summer visitors for granted, but the word is that south of Dublin Bay the tern buffs are so incensed by Rockabill having a clear run that they're tried to start a rival colony of roseate terns on the Muglins, and built a row of tern houses (one good tern deserves another) to facilitate their residence. The potential nest sites may not have survived the past severe winter. But in any case, one wonders if they had planning permission from Dun Laoghaire/Rathdown council for this development? Persons suggesting that such a development would almost certainly be terned down will not be given any attention whatsoever.

Skerries and Balbriggan are the two main sea towns of north Fingal, and they're as different as can be, the difference being emphasised by historic rivalry. It's said that back in the government harbour-building days of the late 19th Century a grant was made available to assist local landowners to make significant improvements to one of the harbours, and this meant war.

Balbriggan may very definitely dry out, but it provides a secure home port for both trawlers and other boats prepared to settle on the mud and sand. Photo: W M Nixon

So eventually the grant was split with half going to improve Balbriggan, and the other half to Skerries, with neither being a total success. If you seek total shelter in either today, you have to be prepared to dry out, while the anchorage off Skerries is also subject to a large tidal whorl which means that when the ebb is running in a strong onshore wind, the moorings are doubly rough and diabolically uncomfortable. And every so often after an exceptional nor'easter, we have another litany of boats driven ashore and Skerries yacht insurance going even further through the roof.

It's a situation which needs proper attention from an administration which is genuinely interested in the port. And the proper development of the harbour at Skerries, while retaining the little old place's special character, is surely something which could be much better done by Fingal Council rather than some remote Mayor of Dublin for whom Skerries will be the outermost periphery, a place seldom visited, if at all.

We've seen it all before. Time was when Fingal was simply the North County, little noticed in the centres of power which were basically Dublin City and Dublin County, their head offices in the heart of the city. But then in 2001 the new four-council setup was created, and the old name of Fingal – never forgotten by those who cherished the area – was revived. A very fine new user-friendly County Hall – it has even been praised by Frank McDonald of The Irish Times – was built in the re-born county town of Swords. Out on the new boundaries meanwhile, the signs went up saying "Welcome to Fingal County". But we old Fingallion fogeys pointed out that as Fingal means "Territory of the Fair Strangers" (i.e the Norsemen rather than the Danes), it was superfluous to be describing it as "the county of the territory", so these days it's just Fingal, and we're happy with that.

Here in Howth, we sort of slipped into acceptance of the new setup. Once upon a time, from 1917 to 1943, Howth had its own Urban District Council. It says much for the place's remoteness from the world that the HUDC was established in the midst of one global war, and quietly wound up in the midst of another. In 1943, Commissioners had to be imposed on the tiny fiefdom to offset the fact that some local interests thought the HUDC existed entirely for their own personal benefit. So at various times since, Howth was run either by Dublin County Council, or even by Dublin City Corporation. We were assured that this latter setup was all to our benefit, as the powers-that-be in City Hall had a soft spot for Howth, sure wasn't it the place where the mammy went every Thursday evening to buy the family's fish, and wouldn't she want to see it looking well?

Maybe so, but when it came to doing something more useful with the harbour, Howth Yacht Club – having re-constituted itself in 1968 from an amalgamation of Howth Sailing Club (founded 1895) and Howth Motor Yacht Club (founded 1934) - found itself dealing with a bewildering variety of government departments as the lowly interests of fishing and its ports seemed to be shifted whenever possible by civil servants who reckoned that banging the drum on behalf of fisheries in particular, and maritime interests in general, was not a shrewd career move for anyone planning a steady progress up the very landbound Irish public service ladder to the sunlit uplands of a long and prosperous retirement.

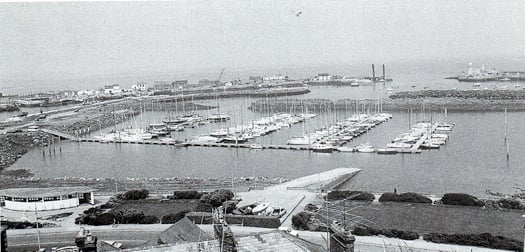

So if at times absolutely nothing seemed to be happening in a harbour which was painfully inadequate for expanding boating and fishing needs, it was partly because the club officers and fishermen's leaders could find it difficult to discern just who in authority could or would make the decisive call. In those days it turned out to be somewhere in the hidden recesses of the Office of Public Works. Suddenly, in 1979, a plan for the major re-development of the harbour was promulgated at official level, with a radical rationalisation planned for its future use. The western part, it was proposed, would become totally fisheries, while the eastern part was to be given over to recreational boating, all of it involving major civil engineering and harbour works projects.

Looking at the successful harbour today, it all seems perfectly reasonable and sensible. But back in 1979 when HYC were presented with a time-limited take-it-or-leave-it choice, the way ahead was not at all clear. Friendships were sundered and family feuds emerged from the heated progress towards accepting the offer that the club agree to vacate its premises on the West Pier - a clubhouse which it had renovated and extended only ten years earlier – and commit itself to the installation, at members' cost, of a marina in the eastern harbour with the obligation to build a completely new clubhouse there.

Today's Howth Harbour didn't happen overnight. This is how it was from 1982 until the new clubhouse was completed in 1987. Photo: W M Nixon

Multiple activities under way at Howth YC this week. The club's setup may seem only natural now, but it was quite a struggle to get there. Photo: W M Nixon

Howth's vibrant mix of a working fishing port and busy sailing centre has provided the ideal setting for the development of a successful visitor and seafood destination. Photo: W M Nixon

It's all history now, but it was done. And done so well by those involved that today it's simply taken for granted. Arguably, it's a compliment to those who created the Howth YC setup, that newer members should seldom wonder how it all came to happen, it just seems so right and natural. And as for those running the club, they in turn have to build on past achievements in dealing with an ever-changing administrative environment in which the changeover to being part of Fingal was only one of several evolutions.

Yet the recent attempt to abolish Fingal was a wake-up call. In Howth we may have wandered into it, but in just a dozen years, a dormant Fingal identity has come quietly but strongly awake. In Howth village it's natural enough, as our backs are turned to Dublin and we look to the rest of Fingal. But even on the south side of the hill, where fine houses face across Dublin Bay and you'd expect a sense of identity with households in similarly choice locations for all that they look north out of Dun Laoghaire, you find that the attraction of visiting the southside has the exotic appeal of going foreign, while those of us more humbly placed in the village, if visiting remote places like Rathmines or Terenure, find it positively unnerving to think of all the houses between us and the sea.

Then too, while Fingal Council has been establishing itself in our hearts and minds, it has been a good time for Howth Harbour. Good fences have been making good neighbours, and though marine administration in government has been kicked from pillar to post, an underlying Department of Fisheries recognition that their harbours cannot be only about fishing has led to a re-think on the use of buildings about the harbour, with Howth becoming an extraordinary nexus of good seafood restaurants, such that on a summer evening, despite the presence of a traditional fish and chip shop, the seafood aroma is of a proper fishing port in Brittany or Galicia. In fact, rents from the hospitality and sailing and marine industries in Howth have now reached such a level that fish landing fees – formerly the bedrock of the harbour economy – only contribute about 10% of the overall income.

The man from County Hall. Fingal Mayor Kieran Dennison is comfortable with his county's busy sailing activities, and the sailors are comfortable with him. He is seen here officially opening the J/24 Worlds at Howth in August 2013. Photo: W M Nixon

As for how we've been getting on with our new masters in County Hall up in Swords, the news is good. Most recently, we've been having direct contact with the current Mayor of Fingal, Kieran Dennison, who hit just the right note when he officially opened the J/24 Worlds in Howth in August 2013. Following that, he was back at the annual Commodore's Lunch in HYC in the dark days of November when a review of the past season lightens the onset of winter, and he was able to tell us that thanks to contacts made at the Worlds, his invitation to visit the America's Cup in San Francisco in September was made even more enjoyable. Those of us who reckoned the only way to visit the 34th America's Cup was on the television screen were reassured by the thought that if somebody was going to represent us in the San Francisco bear-pit, then our Mayor, our very own Mayor of Fingal, was just the man for the job.

So we very much want to keep Fingal in existence and in robust good health, but we appreciate that its current boundaries might be creating a bit of a Ukraine-versus-Russia situation. In particular, the southwest of the county could well be Fingal's Crimea and Donetsk regions. There, relatively new settlements of ethnic Dubs in places like Clonsilla, Castleknock, Blanchardstown could become such a source of trouble that it might be better to transfer them peacefully to administration by either Dublin city or South Dublin before there is unnecessary bloodshed.

The situation arises because, when the boundaries were being drawn, southwest Fingal was set out all the way down to the Liffey. The Fingallion instinct would be to see the border drawn along the Tolka, in other words the M3. But there could be trouble because of the discovery – always something of a surprise – that the Phoenix Park is in Fingal. I could see that when some people find our Fingal includes the Park, they'll want to fight for it, particularly as, in the southeast of the county, the excellent St Anne's Park in Raheny was somehow allowed to slip into Dublin City.

One thing which is definitely not for transfer is the Airport. It is naturally, utterly and totally part of Fingal. For sure, it contributes a fifth of the county's annual income from business rates, making Fingal the economically healthiest Irish county. But we in Fingal have to live with the airport very much in our midst. If Dublin really wants to take over the airport, then a first condition before negotiations even begin would be that all flight paths are to be re-routed directly over Dun Laoghaire and Dalkey. A few weeks of that would soon soften their cough.

Whatever, the recent kerfuffle about Fingal rejecting involvement in administration by an all-powerful Mayor of Dublin has been a powerful stimulant to thinking about how our own county might best be run. Everyone will have their own pet local projects, and most of us will reckon that decision-making in Swords, rather than in some vast and impenetrable office in the middle of Dublin, will be the best way to bring it about. For those of us who go afloat, the fact that Fingal Council shows that it cherishes its long and varied sea coast, rather than preferring to ignore it, is very encouraging. And the fact that this prospering county has some financial muscle all of its own gives us hope that we can build on what the past has taught us, and spread improved facilities to every port. Should that happen, it will in turn benefit Irish sailing and boating generally to a greater extent than would restricted development under one closely-controlled central administration headed by some southside megalomaniac.

Clonshaugh Chosen For Fingal Sewage 'Super Plant'

#Sewage - Clonshaugh in North Dublin has been chosen as the location for the city's new water treatment 'super plant' which has long faced objections from local campaigners.

As The Irish Times reports, a meeting of Fingal County Council yesterday afternoon (10 June) saw the site near Dublin Airport chosen over Annsbrook and Newtowncorduff, both near the coastal towns of Rush and Lusk.

Part of the plan includes the construction of a 26km orbital sewer to collect waste from parts of Dublin, Kildare and Meath, and an outfall pipeline that will eject waste near Ireland's Eye.

Project managers have described the Clonshaugh option as "ecologically and environmentally better" than the alternatives, but campaigners such as Reclaim Fingal chair Brian Hosford argue that "the potential for environmental disaster [with a single large plant] is enormous".

In January 2012, Minister for Health James Reilly raised his own concerns that any potential malfunction at the large-scale facility - second-only in scale to the new water treatment plant at Ringsend - could see huge amounts of raw sewage pumped into the Irish Sea.

Meanwhile, The Irish Times also spoke to a farming family who may lose as many as 40 acres if the 'super plant' gets the go-ahead adjacent to their land.

"I would have to change my whole system of farming if this goes ahead," said 77-year-old PJ Jones, who added that his biggest concern was the smell.

Arrive By Sea!...to the Dublin Bay Prawn Festival

#FestivalExcursion-Those heading for the Dublin Bay Prawn Maritime Festival (26-28 April) in Howth may consider an alternative and new way of reaching the north Co. Dublin fishing harbour with Dublin Bay Cruises which began operations last week, writes Jehan Ashmore.

The excursions run between Dun Laoghaire (East Pier) and Howth and are offered as a one-way trip (in either direction) between the harbours.

Passengers will be able to make their way back to the city-centre from either Dun Laoghaire or Howth harbours by taking the DART train (concessionary price) or use of other public transport links.

For the festival, Dublin Bay Cruises are also providing special 'Prawn Festival Cruises' on Saturday (27 April) with cruises departing Howth Harbour (at 13.30 and 15.30). These cruises will head out around Howth Peninsula and into Dublin Bay before returning back to the harbour.

All the excursions are operated by 'St. Bridget', a 26m steel-hulled vessel with a capacity for around 100 passengers and which has a bar facility serving light refreshments.

In addition there are shorter trips from Howth Harbour to Ireland's Eye and 'round' the island excursions which are operated by Ireland's Eye Ferries and Island Ferries.

Also taking place on the Saturday, as previously reported on Afloat.ie, there is to be a Prawn Push in aid of Howth RNLI beginning at 3pm.

Up Close and Personal: New Boat Tours of Dublin Port

In addition to cruising this stretch of the River Liffey alongside the 'Docklands' quarter, the tour RIB boat will pass downriver through the East-Link toll bridge where visitors will get closer views of the variety of vessels and calling cruise liners from other ports throughout the world.

There will be five daily tours beginning at 10.00am, 12.00pm, 2.00pm, 4.00pm and 6.00pm.Tickets cost €15.00 for adults, €12.50 for students and the charge for senior citizens and children is €10.00.

In addition Sea Safari operate a 'River Liffey' only tour, a Dublin Bay 'North' and 'South' tours which visit Howth Head, Baily Lighthouse, Ireland's Eye and to Dalkey Island and Killiney Bay, where both bay tours provide a chance to spot local marine wildlife of seals, porpoises and sea birds.

- Rib

- Dublin Port

- Dublin Docklands

- Howth Head

- marine wildlife

- Cruise Liners

- Sea Safari Tours

- Dalkey Island

- Port of Dublin

- River Liffey

- Ports and Shipping News

- EastLink

- EastLink Toll Bridge

- Dublin Port news

- Baily Lighthouse

- Killiney Bay

- Seabirds

- Port of Dublin news

- RIBcraft

- M.V. Cill Airne

- Dublin Port cruise liners

- North Quay Wall Dublin

- Dublin Bay tours

- Ireland's Eye