Displaying items by tag: W M Nixon

#oldestyachtclubintheworld – Following WM Nixon's latest blog on Afloat.ie where he gives an account of early Irish yachts and yachting, leading yachting historian Hal Sisk has added to the story of how the sport was formed with claims the amateur sport of sailing became established in the 1850s on Dublin Bay.

Sisk also reveals that contrary to the conventional foundation myth for yachting, the English did not introduce yacht racing in the 1660s. Instead, a once off race is recorded on Dublin Bay where Sir William Petty wrote that he had successfully matched his experimental 30–ft catamaran on several occasions in the winter of in the winter of 1662/3.

In a written comment at the end of Nixon's Saturday blog: Sailing Artefacts Prove Irish Yacht Clubs Are The Oldest In The World, Sisk also asks how significant were the early yacht clubs and were the early yachts truly leisure craft?

He gives as an example, the Stuart royal yachts that were mini warships, built from funds voted for the Navy and in battle with the Dutch in 1673.

Finally, Sisk says the worldwide sport we know today owes more to the pioneering amateurs of Dublin Bay than to the wealthy yacht owners of the 18th and early 19th century. Thus as well as several spectacular silver trophies, the key figures of the Dublin's Royal Alfred YC gave us in the 1850s to 1870s the following yachting firsts:

--World's First National Yacht Racing Rules and Regulations (published by the RAYC in 1872, adopted by the Yacht Racing Association)

--World's First Offshore Racing Club (1868 to 1922)

--World's First Single and Double handed races (1872)

--World's Premier Amateur Sailing Club (1857--)

Add to that the Water Wags of Dublin giving the world the One Design concept in 1887, and we may well ask who made the greater contribution to our sport and who left the greater lasting influence?

Hal Sisk's full comments can be read a the end of the WMN Nixon's blog here.

#yachtclubs – The antiquity of Irish recreational sailing is beyond dispute, even if arguments arise as to when it started, and whether or not the Royal Cork YC really is the world's oldest club in its descent from the Water Club of the Harbour of Cork from 1720. But all this seems academic when compared with the impression made by relics of Ireland's ancient sailing traditions.

In just six short years, the Royal Cork Yacht Club will be celebrating its Tercentenary. In Ireland, we could use a lot of worthwhile anniversaries these days, and this 300th has to be one of the best. The club is so firmly and happily embedded in its community, its area, its harbour, in Munster, in Ireland and in the world beyond, that it is simply impossible to imagine sailing life without it.

While the Royal Cork is the oldest, it's quite possible it wasn't the first. That was probably something as prosaic as a sort of berth holder's association among the owners of the ornamental pleasure yachts which flourished during the great days of the Dutch civilisation in the 16th and 17th Centuries. They were based in their own purpose-built little harbours along the myriad waterways in or near the flourishing cities of The Netherlands. Any civilisation which could generate delightful bourgeois vanities like Rembrandt's Night Watch, or extravagant lunacies such as the tulip mania, would have had naval-inspired organised sailing for pleasure and simple showing-off as central elements of its waterborne life.

Just sailing for pleasure and relaxation, rather than going unwillingly and arduously afloat in your line of work, seems to have been enough for most. Thus racing – which is the surest way to get some sort of record kept of pioneering activities – was slow to develop, even if inter-yacht matches were held, particularly once the sport had spread to England with the restoration of Charles II in 1660.

Ireland had not the wealth and style of either Holland or England, but it had lots of water, and it was in the very watery Fermanagh region that our first hints of leisure sailing appeared. It's said of Fermanagh that for six months of the year, the lakes are in Fermanagh, and for the other six, Fermanagh is in the lakes. Whatever, the best way to get around the Erne's complex waterways system, which dominates Fermanagh and neighbouring counties, was by boat. By the 16th Century Hugh Maguire, the chief of the Maguires, aka The Maguire, had a Lough Erne-based fleet, some boats of which were definitely for ceremonial and recreational use.

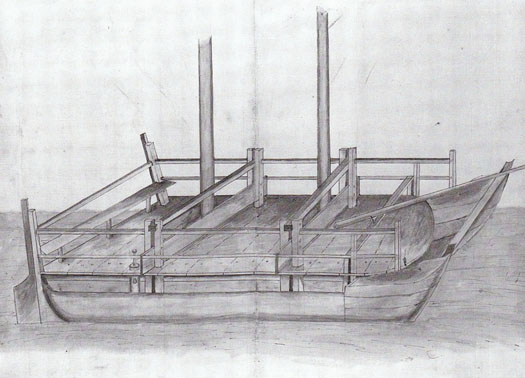

Sport plays such a central - indeed total - role in Irish life that it's highly likely these pleasure sailing boats were sometimes used for racing. However, the first recorded race anywhere in Ireland took place in Dublin Bay in 1663 when the polymath Sir William Petty, having built his pioneering catamaran Simon & Jude, then organised a race with a Dutch sailing vessel and a local "pleasure boatte" of noted high performance. This event, re-sailed in 1981 when the indefatigable Hal Sisk organised the building of a re-creation of the Simon & Jude, resulted both times in victory for the new catamaran. But because a larger sea-going version of the Simon & Jude, called The Experiment at the suggestion of Charles II himself, was later to founder with all hands while on a testing voyage in the Bay of Biscay, the multi-hull notion was abandoned in Europe for at least another two centuries.

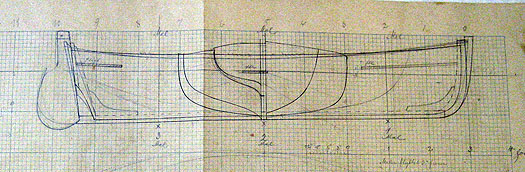

Contemporary drawing of the 17th Century catamaran Simon & Jude, which was built in Dublin and tested in the bay in an early "yacht race" in 1663.

We meanwhile are left wondering just what was this "pleasure boatte" was, and who owned and sailed it. Its existence and good sailing performance seems to have been accepted as unremarkable in Dublin Bay, yet no other record or mention of it has survived.

It was the turbulent life of Munster in the 17th Century which eventually created the conditions in which the first yacht club was finally formed. As the English Civil War spread to Ireland at mid-Century with a mixture of internecine struggle and conquest, the Irish campaigner Murrough O'Brien, the Sixth Baron Inchiquin, changed sides more than once, but made life disagreeable and dangerous for his opponents whatever happened to be the O'Brien side for the day.

Yet when the forces supporting Charles II got back on top in 1660 after the death of Cromwell in 1658, O'Brien was on the winning side. As the dust settled and the blood was washed away, he emerged as the newly-elevated Earl of Inchiquin, his seat at Rostellan Castle on the eastern end of Cork's magnificent natural harbour, and his interests including a taste for yachting acquired with his new VBF Charles II.

But there was much turmoil yet to come with the Williamite wars in Ireland at the end of the 17th Century. Yet somehow as the tide of conflict receded, there seemed to be more pleasure boats about Cork Harbour than anywhere else, and gradually their activities acquired a level of co-ordination. The first Earl of Inchiquin had understandably kept a fairly low profile once he got himself installed in his castle, but his descendants started getting out a bit and savouring the sea. So when the Water Club came into being in 1720, the fourth Earl of Inchiquin was the first Admiral.

In the spirit of the times, having an aristocrat as top man was sound thinking, but this was truly a club with most members described as "commoners", even if there was nothing common about their exceptional wealth and their vast land-holdings in the Cork Harbour area. Much of it was still most easily reached by boat, thus sailing passenger vessels and the new fancy yachts interacted dynamically to improve the performance of both.

Yet there was no racing. Rather, there was highly-organised Admiral Sailing in formation, something which required an advanced level of skill. However, many of the famous club rules still have a resonance today which gives the Water Club a sort of timeless modernity, and bears out the assertion by some historians that, as it all sprang to life so fully formed, the formation date of 1720 must be notional, as all the signs are that there had been a club of some sort for years beforehand.

But either way, it makes no difference to the validity or otherwise of the rival claim, that the Squadron of the Neva at St Petersburg in Russia, instituted by the Czar Peter the Great in 1718 to inculcate an enthusiasm for recreational sailing among Imperial Russia's young aristocrats, was the world's first yacht club. It was no such thing. It was in reality a unit of the Russian navy, and imposed by diktat from the all-powerful ruler. As such, it was entirely lacking the basic elements of a true club, which is a mutual organisation formed by and among equals.

Yet as the Water Club of the Harbour of Cork had no racing with results published in what then passed for the national media, we are reliant on the few existing club records and some travel writing from the time for much of our knowledge of the early days of the Water Club. That, and the Peter Monamy paintings of the Water Club fleet at sea in 1738.

A remarkably well-disciplined fleet. Peter Monamy's 1738 painting of the yachts of the Water Club at sea off Cork Harbour. They weren't racing, but were keeping station in carefully-controlled "Admiral Sailing". Courtesy RCYC

Fortunate indeed are the sailors of Cork, that their predecessors' activities should have been so superbly recorded in these masterpieces of maritime art. The boats may look old-fashioned to a casual observer, yet there's something modern or perhaps timeless in this depiction of the fleet sailing in skilled close formation, and pointing remarkably high for gaff rigged boats as they turn to windward. Only a genuine shared enthusiasm for sailing could have resulted in such fleet precision, and in its turn in a memorable work of art. It is so much part of Irish sailing heritage that we might take it for granted, but it merits detailed study and admiration no matter how many times you've seen it already.

Shortly after Monamy's two paintings were completed, Ireland entered a period of freakish weather between 1739 and 1741 when the sun never shone, yet it seldom if ever rained, and it was exceptionally cold both winter and summer. It is estimated that, proportionately speaking, more people died in this little known famine than in the Great Famine itself 104 years later. While the members of the Water Club would have been personally insulated from the worst of it, the economic recession which struck an intensely agricultural area like Cork affected all levels of society.

Thus the old Water Club saw a reduction in activity, but though it revived by the late 1740s, the sheer energy and personal commitment of its early days was difficult to recapture, and by the 1760s it was becoming a shadow of its former self. Nevertheless there was a revival in 1765 and another artist, Nathanael Grogan, produced a noted painting of Tivoli across from Blackrock in the upper harbour, with a yacht of the Water Club getting under way for a day's recreation afloat, the imminent departure being signalled by the firing of a gun.

The best way to get the crew on board....on upper Cork Harbour at Tivoli in 1765, a yacht of the reviving Water Club fires a gun to signal imminent departure.

However, it was on Ireland's inland waterways that the next club appeared – Lough Ree Yacht Club came into being in 1770, and is still going strong. That same year, one of the earliest yacht clubs in England appeared at Starcross in Devon, but it was in London that the development pace was being most actively set with racing in the Thames for the Cumberland Fleet. Some members of this group, after the usual arguments and splits which plague any innovative organisation, in due course re-formed themselves as the Royal Thames Yacht Club in the early 1800s. But the famous yet unattributed painting of the Cumberland Fleet racing on the Thames in 1782, while it is slightly reminiscent of Monamy's painting of the Water Club 44 years earlier, undoubtedly shows boats racing. And they'd rules too – note the port tack boat on the right of the picture bearing off to give way to the boat on starboard.

Definitely racing – the Cumberland Fleet, precursor of the Royal Thames Yacht Club, racing in the River Thames at Blackfriars in 1782.

The Thames was wider in those days, but even so they needed strict rules to make racing possible. Dublin Bay offered more immediate access to open water, and there were certainly sailing pleasure boats about. When the Viceroy officially opened the Grand Canal Dock on April 23rd 1796, it was reported that the Viceregal yacht Dorset was accompanied by a fleet of about twenty ceremonial barges and yachts. Tantalisingly, the official painting is almost entirely focused on the Dorset and her tender, while the craft in the background seem to be naval vessels or revenue cutters.

This painting of the opening of the Grand Canal Dock in 1796 tends to concentrate on the ceremonials around the Viceroy's yacht Dorset in the foreground, but fails to show clearly any of the several privately-owned yachts which were reportedly also present....

.......but this illustration of the old Marine School on the South Quays in Dublin in 1803 seems to have a yacht – complete with owner and his pet dog on the dinghy in the foreground – anchored at mid-river.

However, a Malton print of the Liffey in 1803 shows clearly what is surely a yacht, the light-hearted atmosphere of waterborne recreation being emphasised by the alert little terrier on the stern of the tender conveying its owner in the foreground Meanwhile in the north of Ireland there was plenty of sailing space in Belfast Lough, while Belfast was a centre of all sorts of innovation and advanced thinking. Henry Joy McCracken, executed for his role in the United Irishmen's rising in 1798, was a keen pioneer yachtsman. As things took a new turn of determined money-making in Belfast after the Act of Union of 1801, some of his former crewmates were among those who formed the Northern Yacht Club in 1824, though it later transferred its activities across the North Channel to the Firth of Clyde, and still exists as the Royal Northern & Clyde YC.

Meanwhile in 1806 the old Water Club of the Harbour of Cork had shown new signs of life, but one result of this was an eventual agreement among members - some of them very old indeed, some representing new blood - that the club would have to be re-structured and possibly even given a new name in order to reflect fresh developments in the sport of yachting. The changeover was a slow business, as it had to honour the club's history while giving the organisation contemporary relevance. Thus it was 1828 before the Royal Cork Yacht Club had emerged in this fully fledged new form, universally acknowledged as the continuation of the Water Club, and incorporating much of its style.

But it was across the north on Lough Erne in 1820 that the world's first yacht club specifically set up to organise racing was formed, and Lough Erne YC continues to prosper today, its alumnae since 1820 including early Olympic sailing medallists and other international champions.

There must have been something in the air in this northwest corner of Ireland in the 1820s, for in 1822 the men who sailed and raced boats on Lough Gill at Sligo had a pleasant surprise. Their womenfolk got together and raised a subscription for a handsome silver trophy to be known as the Ladies' Cup, to be raced for annually – and it still is.

Instituted in 1822, the Ladies' Cup of Sligo YC is the world's oldest continually-contested annual sailing trophy.

Annual challenge cups now seem such a natural and central part of the sailing programme everywhere that it seems extraordinary that a group of enthusiastic wives, sisters, mothers and girlfriend in northwest Ireland were the first to think of it, yet such is the case. Or at least theirs is the one that has survived for 192 years, so its Bicentenary in 2022 is going to be something very special.

Those racing pioneers of the Cumberland Fleet had made do with new trophies freshly presented each year. And apparently the same was the case initially at Lough Erne. But not so very far down the road, at Sligo, somebody had this bright idea which today means that the museum in Sligo houses the world's oldest continually raced-for sailing trophy, and once a year it is taken down the road to the Sligo YC clubhouse at Rosses Point to be awarded to the latest winner – in 2013, it was the ever-enthusiastic Martin Reilly with his Half Tonner Harmony.

The Ladies Cup was won in 2013 by Martin Reilly's Half Tonner Harmony. Pictured with their extremely historic trophy are (left to right) Callum McLoughlin, Mark Armstrong, Martin Reilly, John Chambers, Elaine Farrell, Brian Raftery and Gilbert Henry

However, although the Ladies' Cup may have pioneered a worthwhile trend in yacht racing, it wasn't until 1831 that they thought of inscribing the name of the winner, and that honour goes to Owen Wynne of Hazelwood on the shores of Lough Gill. But by that time the notion of inscribing the winners was general for all trophies, and a noted piece of the collection in the Royal Cork is the Cork Harbour Regatta Cup 1829, and on it is inscribed the once-only winner, Caulfield Beamish's cutter Little Paddy.

The name of noted owner, skipper and amateur yacht designer Caulfield Beamish came up here some time back, when we were discussing how in 1831 he took a larger new yacht to his own design, the Paddy from Cork, to Belfast Lough where he won a stormy regatta. So you begin to understand the mysterious enthusiasm people have for sacred relics when you see this cup with its inscription, and realise that it's beyond all doubt that this now-forgotten yet brilliant pioneer of Cork Harbour sailing development personally held this piece of silverware.

Caulfield Beamish's new cutter Paddy from Cork (which he designed himself) winning a stormy regatta in Belfast Lough in 1831

The Cork Harbour Regatta Cup of 1829.....Courtesy RCYC

....and on it is inscribed the winner, Caulfield Beamish's earlier boat, Little Paddy, which he also designed himself. Courtesy RCYC

Another pioneer in yacht racing at the time was the Knight of Glin from the Shannon Estuary, who in 1834 was winning all about him with his cutter Rienvelle, his season's haul including a silver plate from a regatta in Galway Bay – it's now in Glin Castle – while he also seems to have relieved fellow Limerick owner William Piercy of £50 for a match race in Cork Harbour against the latter's cutter Paul Pry.

The lads from Limerick hit Cork. William Piercy's Paul Pry racing for a wager of £50 against the Knight of Glin's Rienvelle in Cork Harbour in 1834. When Paul Pry won Cork Harbour Regatta a few weeks later, the band on the Cobh waterfront played Garryowen. Courtesy RCYC

But of all the fabulous trophies in the Royal Cork collection, the one which surely engenders the most affection is the Kinsale Kettle. It goes back "only" to 1859, when it was originally the trophy put up for Kinsale Harbour Regatta. But this extraordinarily ornate piece of silverware was not only the trophy for an annual race, it was also the record of each race, as it's inscribed with brief accounts of the outcomes of those distant contests.

An extraordinary piece of Victorian silverware. The "Kinsale Kettle" from 1859 is now the Royal Cork YC's premier trophy.

Today, it continues to thrive as the Royal Cork Cup, the premier award for Cork Week. The most recent winner in 2012 was Piet Vroon with his superb and always enthusiastic Tonnere de Breskens. The fact that this splendid ambassador for Dutch sailing should be playing such a central role in current events afloat here in Ireland brings the story of our sport's artworks and historical artefacts to a very satisfactory and complete circle.

More tea, skipper? The current holder of the Kinsale Kettle, aka the Royal Cork Cup, is Piet Vroon of Tonnere de Breskens. Photo: Bob Bateman

Irish Sailors Show the Way for Chill–Out Sailing

#chillout – As the sailing community ponders the global fall-off in casual sailing numbers, leading sailor Ken Read reckons that one of the reasons is because our sport is getting too serious. He says it's time for most sailors to take a chill-pill. W M Nixon muses on how this suggestion is reflected in Ireland.

Ken Read, former Volvo World Race skipper of notable success, and holder of heaven only knows how many major championships and sailing records, is these days the President of North Sails. A nice little earner, you might say. Let's hope so. But there's much more to it than that.

Being President of North is top of the tops. Time was when the head honcho at Hood Sails, particularly when it was Ted Hood himself, was the special one, filling a unique and highly visible position in the big picture. And other leading global sailmaking brands have also been on this pinnacle from time to time. But these days, Ken Read is the man. He holds the key point in the middle of the triangle formed by the marine industry on one side, the local, national and international sailing organisations on the other, and the sailors themselves on the third. By the nature of their trade and the way it operates, sailmakers are connected every which way, and the world's top sailmaker speaks for all.

So when the President of North Sails advocates a change of sailing attitude at a recent convention of J Boat dealers in America, the sailing world is well advised to take notice. It may be that he said things that many of us have been saying in a different form for many years. But the fact that it was said by the President of North Sails, and said in a concise and forceful yet good-humoured way, uniting many strands of thinking, was something which gave it an impact which no other leading commentator could achieve.

But then Ken Read has always been unique, ever since he was clearly having the time of his life as he rose to international prominence through the ranks of the J/24 Class. He seems to have an enviable gift of knowing how to party when it's right, and how to sail intensely well when the situation demands it. He inspires a very special loyalty among crews, and an admiration and affection among people generally when the big sailing events come to town.

Galway's Volvo Race stopovers provided the classic case in point. Long before selfies became all the rage, just about every club sailor who was next or near Galway docks came proudly home with a photo of themselves and their mates with Kenny Read. As for the great man himself, as the fleet raced away down past the Cliffs of Moher at breakneck speed, he still found time to post a message saying how much he'd enjoyed his time in Galway, sending out a cheery stream of consciousness about this great harbour town with a pub on every corner, and everybody in those pubs wants to buy you a beer, and the greatest golf links he'd ever played down at Doonbeg, so what's not to like?

But just in case anyone was in any doubt about how he'd fully immersed himself in the Galway and Irish thing, as the fleet had headed out through the Galway lock, here was the man himself in a Paddy hat you'd need a licence for. We gave you a glimpse of it at the top this morning, but the full impact needs a bit of space, so here it is again in untrimmed glory. It's something to be savoured, though I doubt you'll find it displayed on the walls of the North Sails boardroom.

The Full Monty. Only a man very comfortable with himself would set out to go to sea in the most public way possible, and attired like this. Photo: David Branigan

Ken Read got his main point made immediately at the J Boat gathering. He wants recreational racing to take a chill pill. He argues that the message is simple: the harder we play, and the more we invest in our recreation, the fewer people will want to take part in the game.

You'd guess the key phrase is "recreational racing". In other words, he's talking of what you and I do in club racing, at local, regional and class championships, and in offshore races on the nearest bit of open water.

Obviously we're not talking Olympic aspirations, or indeed sailing towards one of the 143 world titles which sailing offers to dedicated participants. But if we did want a scapegoat for people being turned off sailing, I'd be minded to blame the dominance of the Olympics in the public's thinking about minority sports.

The Olympic circus is the sow that eats others' farrow. It takes up little specialist sports, and then forces them into unnatural shapes in order to attract their brief moment of global Olympic attention. And once it has them hooked, it dictates the amount of media interest they have to continue to generate in order to stay in the Olympic lineup. To do this, they contort themselves and their events even further in every unnatural way possible in order to get what is, ultimately, no more than the most ephemeral passing interest, and that from people whose attention really isn't worth the effort in the first place.

Sailing is essentially about participation, it's not naturally spectator friendly. The only truly absorbing way to watch a yacht race is by taking part in it, and enjoyable yacht races can take many forms. But as the Olympic juggernaut gathered speed and power during the past eighty and more years, the Olympic "ideal" of the purest possible yacht racing, with windward starts all staged from committee boats as clear as possible from the influence of the land on the breeze, and preferably in a tide-free zone, became the dominant theme. Even the most homely club sailing programmes found themselves being forced by fashion into the strait jacket of aping the sacred "Olympic course", and raced by one designs too.

But in his presentation to the J Boat men, Ken Read has blown it all out of the water. The Must Read list is:

- Rally and pursuit races are fun, and gaining in popularity.

- Get rid of the AP flag; people want to sail, not float around waiting for perfect conditions.

- Stop worrying that the starting line is off by 5 degrees; start the race

- Get rid of uncomfortable gut hiking off the lower lifelines

- All spinnakers should be coloured; no more white!

- Start some races downwind

- More variety of courses; not only W-L

- Increased use of reaching legs, particularly with boats that can plane

- Involve youngsters more in big boat sailing; not all want to do dinghies.

- More public access to the water, then sailing would become even more important

- Pros should be helping the amateurs by being available at regattas to give help and guidance.

It's a wish list which carries a couple of real stings in the tail. Making recreational waters more publicly accessible immediately suggests that you'll need public employees and regulators to run such access amenities, not only in supervising the launchings and retrievings, but also in keeping the facilities in good order. With experience painfully teaching us that what's everybody's business is nobody's business, the increase of public access to an intensely personal vehicle sport like sailing is quite a challenge.

As for suggesting that the top pros should be available at regattas to help amateurs, that's a tricky one. With much of modern sailing already having a pro-am mix in many events, you can see that there'll be competition to get the attention of top pros, and money will talk. That said, every so often you hear of sailors of truly global stature such as Robert Scheidt of Brazil, whose presence at some ordinary event manages to enhance everyone's day afloat.

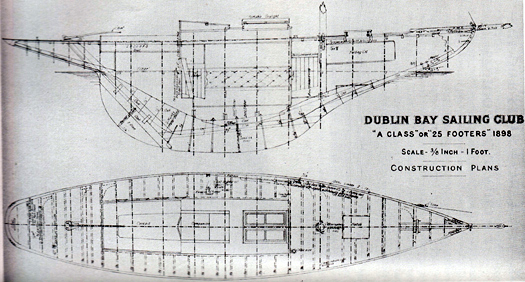

But as for Irish sailing learning from the Read programme, it's really more a case of learning anew. For instance, this business of getting all ages involved in big boat racing. Well, we featured it here a couple of weeks ago with our analysis of the success of Dublin Bay Sailing Club. Inevitably, some subsequent commentators complained that while Dublin Bay may provide dinghy racing at mid-week, Saturdays are dominated by keelboats and particularly cruisers. Instead of being an undesirable situation, this sounds rather like what Ken Read is advocating.

The fact is, cruisers are simply much less hassle to organise for weekend racing. They're afloat and ready to go, you can even use them as changing rooms, they don't need crash boats, and they can provide that easygoing sociable atmosphere which needn't involve a debilitating level of commitment. Yet it gets people out enjoying sailing - and they come back for more. Dinghies by contrast are a flighty bunch, and you've no sooner gone to all the trouble of setting up regular Saturday racing for them than you find they're on their trailers, haring down the motorway to some distant regional championship.

Read's opening suggestion about rally and pursuit races will ring a special bell for anyone whose formative sailing years were at Ballyholme Bay on Belfast Lough. Although BYC is now the north's leading performance and dinghy events club, its membership is eclectic and its fleet diverse, so for as long as anyone can remember, they concluded their traditional season with a pursuit race.

These days their season is virtually year-round, but the Menagerie Race, as it's sometimes known, is still sailed every September. It generates excitement at all levels. Beforehand, with handicaps being taken at the start, there's the fascination of the handicapper's calculations to allot starting times for each class and the many individual boats from small dinghies to large cruisers. Then on the day itself, the weather is of special interest as different conditions better suit different boats. And then the finish is one of high excitement, as the final leg is sailed across the bay towards the line close off the club, a time of drama as everyone from biggest to smallest closes in towards a finish which may be decided by inches – it has not been unknown for a couple of crewmembers to be straining on the stemhead as they hold the spinnaker pole out forward well beyond the pulpit to gain a couple of feet.

Unlike your usual handicap race where the result may have to wait for the finish of the last boat across, a pursuit race provides a finish which is instantly satisfying for the winner at least, and also for spectators of limited attention span, which is just about all of them these days.

Lufra in her youth, tearing along on the Clyde in the 1890s. Photo courtesy Iain McAllister

As anyone with experience of sailing at Ballyholme will know, the end-of-season Menagerie Race, as its quaint name suggests, goes back a long way. But it's usually better known as the Lufra Cup, and has been known as such since the mid-1940s, when it was presented for a race which was already a much-loved part of the programme.

So who or what was Lufra? In the 19th and early 20th Centuries, the romantic Scottish-flavoured novels of Sir Walter Scott were best sellers. As the new sport of yachting developed, on both sides of the North Channel the work of Scott provided a fertile source of interesting names for boats – an entire class, the 18ft Belfast Lough Waverleys established 1903, derived all their evocative names from his long sequence of Waverly novels.

Lufra was a dog, but a noble and swift one. He figured in Scott's poem The Lady of the Lake (1810), a title which was itself borrowed from the Arthurian legend, but equally has since been borrowed again to name more inland-cruising water-buses than is decent. Whatever, Scott's long narrative poem recounted the usual bloodthirsty Scottish melodrama, set this time in the Trossachs. But from a cast which was large if not quite in the thousands, the character who stays in the mind is "brave Lufra, the fleetest hound in the North".

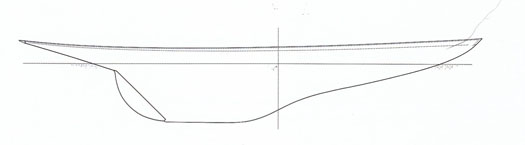

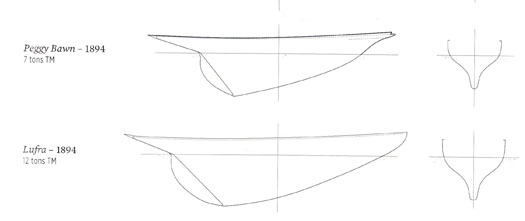

You'd think a unique and swinging name like that – I've always heard it pronounced "loof-rah" – would be encouragement enough to build a boat, and one of gallant performance and character at that. But it wasn't until 1894 that the first boat we know of called Lufra appeared from the busy G L Watson design office. Built by P R MacLean of Rosneath for T K Laidlaw of Glasgow, Lufra came at an interesting time of design development. With the appearance of the spoon-bow with the successful 10-Rate Dora in 1891 (she also had a centreboard, but that's by the way), the Watson office had started moving away from the clipper or fiddle bow, and with the big boats Britannia and Valkyrie in 1893, they developed a new kind of keel, more definably an appendage to the hull, and with a more marked toe which greatly improved windward ability.

The timeless profile of Britannia in 1893. She still looked up-to-date at the end of her life in 1936, by which time her shape was also used for offshore racers and fast cruisers.

The profiles and hull sections of Peggy Bawn and Lufra. Though they were broadly similar below the waterline, the fact that Lufra had an above-water profile similar to Britannia made her seem much more modern

But most yachtsmen, particularly those with an interest in occasional cruising, are conservative types. So for several years the Watson team were still being commissioned to design new boats of an older type, with fiddle bow, fairly slack and deep hull sections, and a deep heel to the keel. Hal Sisk's 1894 Watson-designed, Hilditch-built classic Peggy Bawn is a good example of this type. She may have been designed a year after Britannia, but her hull shape is light years away from the high-performance Britannia, whose hull continued to look state-of-the-art right up her unhappy scuttling by Royal Command in 1936.

Admittedly when launched Britannia was though of solely as a racing boat, but by the time of her enforced demise, offshore racers and fast cruisers were replicating her hull type. As for Lufra in 1894, she was somewhere between the two types. She had a spoon bow but similar hull sections to Peggy Bawn. However, above the waterline, the 40ft LOA 12-tonner Lufra was a miniaturised image of Britannia.

She was first brought to Northern Ireland from the Clyde in 1937 by Howard Finlay, who sailed on both Belfast and Strangford Loughs. Anyone who thinks of the 1930s and '40s as a dowdy period in Ireland north and south will find the photos of Howard and his mates aboard thenewly-bought boat something of an education. Howard himself had the chiselled good looks of a matinee idol designed to have a pipe clinched in his teeth, while his crew had the style of supporting actors in a Jimmy Cagney movie, or even an early Bogart film. You expect them to burst into exuberant song at any moment, or start shooting.

The gang's all here. Howard Finlay (second left) and his crew of characters aboard Lufra in 1938. Photo courtesy Paul Finlay

Initially in the Finlay ownership, Lufra was white, but later he painted her black which emphasised the Britannia resemblance, while she was kitted with tan sails which looked very handsome indeed. While still white, she took part in Ballyholme's end-of-season Menagerie Race of 1943, which she won. But as there was no decent prize available, Howard put up the Lufra Cup for the 1944 race.

You might wonder that racing was going on at Ballyholme in the midst of World War II. But as Belfast itself was such a hectically busy place with building and repairing warships, aircraft and so forth, it was decided that it made sound welfare sense to encourage the key workers and managers, most of whom were doing incredibly long hours, to keep up their sporting activities in their brief free time. Thus it was only at the height of the war in 1940 that all sailing was cancelled, and by 1943 sailing was busy again, as there was no petrol available for motoring and other rival vehicle pursuits.

In those days, the Ballyholme Bay class, curious little 23ft keelboats with a tiny coachroof, were the hot racing things of Ballyholme despite not having spinnakers - they just whiskered out the jib. But despite this, as the finish of the 1944 race approached with a half mile broad reach across the bay, the top Ballyholme Bay Class boat, Jack Cupples' Caleta, seemed set for a win. But coming up rapidly from astern, Howard Finlay brought Lufra gybing smoothly round the last mark. Somehow his crew had the enormous spinnaker up and drawing for that final half mile leg, and they swept by Caleta to take the cup on the line, and a blurry Box Brownie photo records it all.

Lufra sweeps across the line to win the 1944 "Menagerie Race" at Ballyholme, and so become the first winner of the Lufra Cup. Photo courtesy Paul Finlay.

It was pursuit racing at its best, as close astern was one of the 30ft LOA Belfast Lough Stars (near sisters of the Dublin Bay 21s, but setting a gunter mainsail instead of gaff with tops'l) and then the rest of the fleet were in within minutes. The handicapper who'd set the starting times was delighted. But some Bay Class types weren't quite so chuffed, and suggested that as Howard Finlay had presented the new cup, the right thing to do would be to hand it on to the boat which finished second. He told them very precisely what they could do with that notion.

Over the next few years, Lufra was in the frame now and then, though the handicapper made sure she never won her cup again. But by the 1950s she was becoming very expensive to run, and in those recessionary times, she was unsellable. In fact, her lead ballast keel was worth more than the boat complete. So the keel was removed and sold, and this most handsome boat was laid up afloat in the little quarry hole harbour in Donaghadee in the hope that the good times would return. But for Lufra, the good times never did return. She rotted and sank, and when the quarry hole was being excavated to become Ireland's first coastal marina in the late 1960s, the last surviving relics of "the fleetest hound in the North" were dredged up and taken away to a landfill.

The restored 1903-built Belfast Lough Waverley Lilias (Jeff & Janet Gouk) was the 2011 winner of the Lufra Cup. Photo: W M Nixon

Yet the Lufra Cup lives on, and the list of its winners gives us a spare yet eloquent account of the sailing story at Ballyholme. Most appropriately, in recent years some of the winners of this trophy honouring Walter Scott's "fleetest hound in the North" have been boats of the old Waverley Class, now undergoing revival with impressive restoration projects. And years ago, when I was battling with racing Insect and Swallow class boats at Ballyholme, a frequent winner was a boat like a big sister of Lufra, Harry Townsley's 15-ton gaff cutter Anolis, which could go like a train on a reach in the kind of race Olympic idealists might sniff at, yet it was exactly what the punters wanted.

The winners over the years have included everything from a Laser (1993, and again in 2007, when sailed by Puppeteer designer Chris Boyd) to 1720s, with just about every type in between, and up or down too. I don't think an Optimist has ever won it yet, so current top cruising man Ed Wheeler has held the record for smallest winning boat since 1958, when he took the cup with his International Cadet.

Many of today's junior sailors may know little of the Cadet, though it still sails. Basically, it was a pram-bowed 10ft chine dinghy built (usually as DIY) in ply to a design by Jack Holt, who later designed the Mirror. The concept of the Cadet was as a mini-version of grown up racing dinghies, a proper training boat with a Bermudan rig which benefited from fine tuning, and setting a spinnaker.

But they were so very very small. The great Wic McCready, Northern Ireland's top junior sailor in his day, was a big lad who grew quickly. In his final year racing Cadets, in light weather he might be seen reposing with as much comfort as he could find by sticking his feet out over the stern. So when you saw a Cadet with Anolis thundering up astern and the finish line just feet away, it was very much little and large. As Ed Wheeler recalls it, crossing the line with Anolis's battering ram bowsprit right above your head concentrated the mind something wonderful.

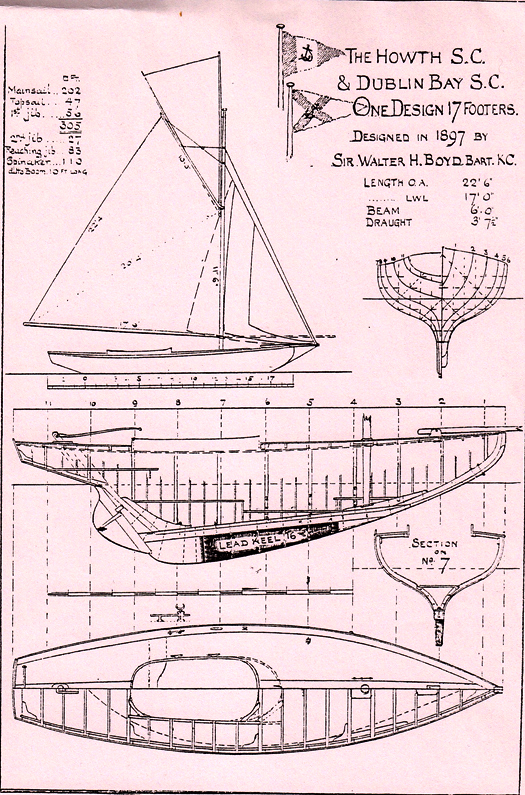

So with the popularity of racing such as that provided for all ages in cruisers by Dublin Bay SC, and the golden thread of the Lufra Cup pursuit race at Ballyholme, it seems to me that maybe we're fulfilling many of the Ken Read objectives in Ireland already. As to setting unorthodox courses sometimes with pier starts, here in my own home port of Howth the 116-year-old Howth 17s were for a time strait-jacketed into Olympic courses which were much less stimulating than their time honoured courses in the interesting waters in and around Ireland's Eye, with handy pier starts just a few minutes sail from the anchorage, instead of having to sail for miles in search of the committee boat.

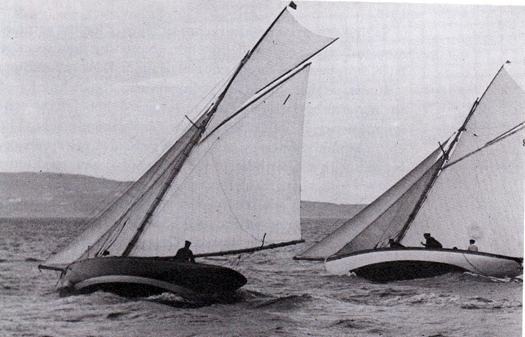

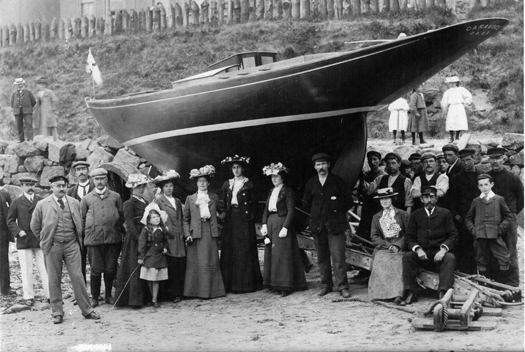

The Howth 17s sweep along in style after making a pier start during the 1930s. Having been making pier starts since 1898, there were attempts after 2000 to get them to use Committee Boat starts. But these days they find that a pier start, with the line only a very few yards from the harbour anchorage, is the option preferred by most crews. Photo: W N Stokes

The result is a revival of Howth 17 racing, particularly in the amorphous area of Saturday afternoon racing, when modern life presents too many distractions and other duties to people who would otherwise be sailing. The convenience and charm of handy starts and racing in very inshore waters seems to have spread, and the word is that the SailFleet J/80s, which will be based in Howth again this year, would also like some convenient pier-starting races in their programme.

So maybe we're going to reach the stage of Olympic sailors being told that they're welcome to keep their sterile starts, and windward-leeward courses far from land, the rest of us prefer a different emphasis. Except, of course, that at the 2012 Olympics, for the final races the fleets were brought very close inshore to facilitate spectators at Weymouth.

It seemed like a case of the tail wagging the dog. And if the racing had been continued offshore, with clear winds and plenty of it, Ireland might well have come home from the 2012 Olympics with a Sailing Bronze. So maybe the real message is, let's make sailing more fun...........except for the Olympics.

Ireland's West Coast – Special Boats & Big Hearted Sailors

#historicboats – These days we're told of the growing disparity between the economic recovery of Ireland's eastern region, and the relative economic stagnation of some of the rest of the country. But W M Nixon suggests that, for one part of the western seaboard at least, there's a special vitality to life around boats which challenges this perception, and could usefully be emulated elsewhere. And he signs off with a thought-provoking conclusion.

Connemara, Conamara. Spell it as you wish, but The Land of the Sea on Connacht's most westerly coast fires the imagination and inspires the spirit. It's a place of the mind as much as a place of wild mountains where rocky inlets wind their way deep into rugged country. So while purists might define it exclusively as the much intertwined coastline with its myriad islands between Spiddal and Killary, many of the rest of us can be so inspired by that special Connemara quality that we reckon it runs all the way from Galway Bay to Achill. And anyone from that magic coastline, or indeed anyone who has been inspired by it, carries the spirit of Connemara with them wherever they may be.

The boat people you meet out there, each with their own unique and often ambitious maritime agenda, will send you on your way re-enthused about boats and places and their many possibilities. And when someone from another place or indeed another country decides that it's in Connemara their true self and fulfilment is to be found, far from being seen as exiles they are instead seen as a new focal points for their old groups, and their soul-mates from times past descend on them in Connemara for inspiration and mental re-birth.

This weekend, the boat men from Clondalkin in outer Dublin are journeying to Renvyle on the furthest far west coast to help one of their own in his boat restoration programme at a storm-battered corner on a bit of coast which was almost washed away in the winter's seemingly endless climatic violence.

The men of Clondalkin are the community group who built and sail and continue to lovingly maintain the large Galway Hooker Naomh Cronan. Recently, they've been busy enough with replacing some planks on their hefty big boat. But their key organiser Paul Keogh is mindful of the fact that one of their own, Paddy Murphy, is in the west, living on an Atlantic point out beyond the old Oliver St John Gogarty house which is now the hotel at Renvyle.

They dreamed the dream, and they made it happen. Key movers in the Naomh Cronan story were Stiophan O Laoire (left) and Paul Keogh, seen here at Poolbeg Y & BC as they come forward to accept a prize on behalf of the crew from Johnny Wedick, Hon. Sec. of the Dublin Bay OGA. Photo: Dave Owens

And between Paddy's house and the sea, beside a little hidden slipway which serves small boats which undertake the risky but rewarding challenge of harvesting Ireland's most fish-filled waters, the restoration project on the Aigh Vie is proving to be a demanding task. So this weekend the Keogh team – precise numbers unknown until everyone checks in this morning – are on site to re-caulk the Aigh Vie in a wild weekend of communal energy.

On the Atlantic frontier at Renvyle, the Aigh Vie is under her roof, tilted over to port to facilitate work under the starboard side of the hull. Photo: W M Nixon

For the Aigh Vie is one very special vessel. She's one of the Manx fishing nobbies which reached their ultimate state of development in the first twenty years of the 20th Century before steam power and then diesel engines took over. The nobby evolved to an almost yacht-like form through vessels like the 43ft White Heather (1904), which is owned and sailed under original-style standing lug rig by Mike Clark in the Isle of Man, and the 1910 Vervine Blossom, now based in Kinvara, which was restored by Mick Hunt of Howth, but he gave her a more easily-handled gaff ketch rig which looked very well indeed when she sailed in the Vigo to Dublin Tall Ships Race in 1998.

Mike Clark's Isle of Man-based 1904-built Manx nobby White Heather sets the original standing lug rig.

The 1910-built Manx nobby Vervine Blossom was restored by Mick Hunt in Howth, and is seen her making knots under her gaff ketch rig at the start of the 1998 Tall Ships Race from Vigo to Dublin. Photo: David Branigan

It takes quite something to outdo the provenance of these two fine vessels, but the story of Aigh Vie (it means a sort of mix of "good luck" and "fair winds" in Manx) is astonishing. It goes back to the sinking of the Lusitania by a German U Boat off the Cork coast in May 1915, when the first boat to mount a rescue was the Manx fishing ketch Wanderer from Peel, her crew of seven skippered by the 58-year-old William Ball.

They came upon a scene of developing carnage. Yet somehow, the little Wanderer managed to haul aboard and find space for 160 survivors, and provide them with succour and shelter as they made for port. In due course, as the enormity of the incident became clear, the achievement of the Wanderer's crew was to be recognised with a special medal presentation. And then William Ball, who had been an employee of the Wanderer's owner, received word that funds had been lodged with a lawyer in Peel on behalf of one of the American survivors he'd rescued. The money was to be used to underwrite the building of his own fishing boat, to be built in Peel to his personal specifications, and the result was his dreamship, the Aigh Vie, launched in 1916.

Over the years, the Aigh Vie became a much-loved feature of the Irish Sea fishing fleet. Tim Magennis, current President of the Dublin Bay Old Gaffers Association, well remembers her from his boyhood days in the fishing port of Ardglass on the County Down coast. In time, she was bought by the legendary Billy Smyth of Whiterock Boatyard in Strangford Lough, who gradually converted her to a Bermudan-rigged cruising ketch with a sheltering wheelhouse which enabled the Smyth family to make some notable cruises whatever the weather. His son Kenny Smyth, who now runs the boatyard with his brothers and is himself an ace helm in the local 29ft River Class, recalls that the seafaring Smyth family thought nothing of taking the Aigh Vie to the Orkneys at a time when the average Strangford Lough cruiser thought Tobermory the limit of reasonable ambitions.

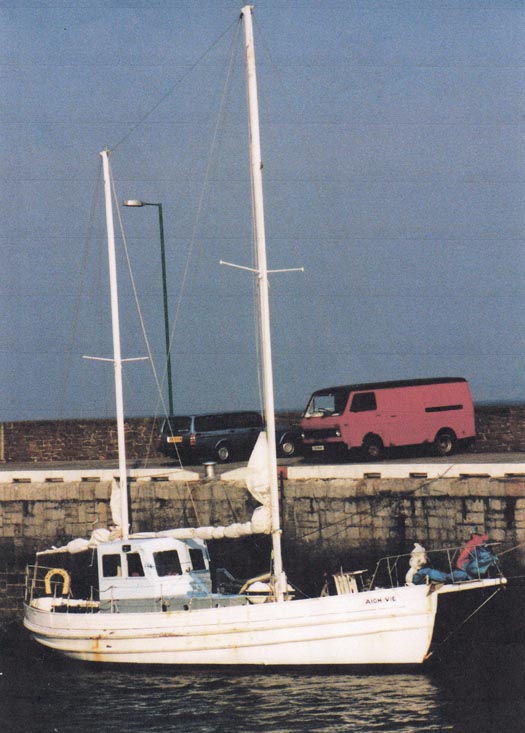

Aigh Vie as she was when bought by Paddy Murphy from Billy Smyth of Strangford Lough.

First sail with the newly-bought ship. Aboard Aig Vie heading for Dublin down Strangford Lough, the crew includes Paddy Murphy (left) and Tim Magennis (centre)

It's some years now since Paddy Murphy bought the Aigh Vie, and sailed her back to Dublin with his crew including Tim Magennis. But around the same time, Paddy was moving his base west to Renvyle, where he reckoned his skilled trade as a blacksmith, and his talents in traditional music and folklore, would provide him with a living in the area where he felt most at home.

As for the Aigh Vie, clearly she was reaching an age where work needed to be done. And he was minded to restore her to something more nearly approaching her original 1916 configuration. So somehow or other, he took the big boat west on a truck, managing to negotiate those little winding roads through Tully Cross and down to his place by the sea, where she went under a roof and work began.

The hull of the 1916-built Aigh Vie as seen in Renvyle shows the remarkably yacht-like lines of the Manx nobby.........Photo: W M Nixon

.........in what was one of the last of the sailing type to be built before steam power took over. Photo: W M Nixon

It has been going on for some time now. The problem with being right on the frontier of Ireland's Atlantic weather is that no sooner do you start on some new area of timber repair and replacement, than the previous restoration section almost immediately starts to become weathered. Working largely on your own, you end up feeling you're going round in circles. So that's why the men from the Naomh Chronan are in Renvyle today to give the Aigh Vie project a mighty push forward.

For there's no doubt that while there's a lot done, there's a lot more still to do. But it does get done eventually if you keep the faith, and I was there back at the beginning of December to cheer Paddy along with all the usefulness of a hurler on the ditch. But at least I was accompanied by Dickie Gomes, who knows a thing or two about long-term boat restoration, as it took him 27 years to bring his 102-year-old Ainmara successfully back to life. But he did it so well that she won the Creek Inn Trophy for "Best in Show" at last summer's Peel Traditional Boat Weekend in the Isle of Man.

A bit of mutual support between two owners of vintage wooden boats – Paddy Murphy and Dickie Gomes in Aigh Vie's shed at Renvyle. Photo: W M Nixon

Nevertheless I've to confess that sometimes I wonder if wood is worth the trouble. Before getting to Renvyle, we'd called by with Jamie Young at Killary Adventure Centre for bit of a love-in with his alloy-built Frers 49 Killary Flyer which - as Brian Buchanan's Hesperia IV - was winner of the Round Ireland Race 1988 under the command of Dickie Gomes. Except that you won't see that fact in histories of the Round Ireland. Because for 1988's race, she sailed as the sponsored entry Woodchester Challenger, and thus was not entitled to the top prize, despite having the best corrected IOR time in the fleet.

But everyone in the know knows that Gomesie won, particularly the crew of Denis Doyle's slightly larger Frers sloop Moonduster. The two boats had been neck and neck running past the Blaskets, and suddenly Hesperia's spinnaker shredded. But Dickie had his crew so well drilled that one half of them had a replacement chute up and drawing before the other half had finished getting in the remains of the torn sail. The boat scarcely missed a beat in her rapid progress, and when the whole business was completed in about three minutes flat, there was a round of applause from Moonduster. You'd sportsmen doing the Round Ireland in those days.

As it happens, one of Hesperia's crew for that neat bit of work was Kenny Smyth, so it made it more than appropriate that we were going on to see the Aigh Vie on which he cut his offshore sailing teeth. But it was good to linger for a while at Jamie's snug place, and marvel at how he, with aid from the ingenious folk of the west, had contrived a slip and an angled trolley so that Killary Flyer can be hauled on site into a sheltered corner, for she's a big lump of a boat to be handling ashore.

She's a big boat to be hauling on a slip in a remote corner of Mayo. Early December beside Killary Fjord, and Jamie Young of the Adventure Centre with Deirdre and Dickie Gomes and the Frers 49 Killary Flyer ashore for the winter. Deirdre was a fulltime member of the boat's crew when Dickie successfully skippered her offshore as Brian Buchanan's Hesperia IV. Photo: W M Nixon

It was some time in the New Year that we heard the shocking news. One of the most severe storms had twirled the Flyer up like a toy boat from her sheltered corner, and deposited this Frers masterpiece on her ear. Jammed in against the steep shore, she was trapped as the tide came in, and the hull was flooded with severe damage to the electrics and electronics.

But this is the west, where they're accustomed to overcoming massive challenges. The extraordinary Tom Moran of Clew Bay Boats played a key role in a salvage project which saw a temporary road being built so that a giant crane could be positioned for the delicate job of inching the big boat back upright. That done, she could then be moved to Tom's place at Westport for restoration to begin.

A couple of dents in aluminium? No problem. Following her brief episode of aviation, Killary Flyer's hull is already made good at Clew Bay Boats in Westport. Photo: W M Nixon

The whole business has been a marvellous advertisement for the effectiveness of hull construction using modern marine alloys. When aluminium was first created as the "Metal of the Future" two centuries ago, only the Emperor Napoleon could afford to have a cutlery set made in this exotic stuff. And though an early alloy boat put afloat in Lake Geneva performed reasonably well, as soon as a boat built with it was put into the salty sea, it just melted away.

But over the years the formulas have been adjusted to be corrosion proof in sea water, such that nowadays it's the ideal material for little boats which are going to have hard usage yet little maintenance, such as angling boats and the nippy craft used by rowing coaches.

And if you have a low-maintenance alloy hull yet give it a bit of cosmetic attention, it will look very well indeed, but it's not essential. As for the rough and tumble of life afloat, if you crash into a quay wall with a traditionally built wooden boat, she'll become shook from bow to stern – you never really know where the underlying structural damage ends, if at all. As for GRP and carbon or whatever, the damage will be more localised, but it still gets holed, and messily with it at that, while bulkheads may shift to an unknown degree

But a steel or aluminium hull will generally just be dented, and very locally at that. Repairs are manageable, even if it's skilled specialist work. So there's a lot in favour of steel and alloy. But steel rusts, and it never rusts quicker than in hidden pockets in the structure. But with remarkable advances in alloy welding and building techniques, the advantages of modern corrosion-free alloy construction become more evident every year for boats that are really going to be used, and not just seen as marina ornaments.

The Killary Flyer experience is ultimately a telling argument in favour of alloy construction. The hull was only dented in a couple of places where it was actually in direct contact with outcrops on the foreshore. Any dents have already been repaired by Tom Moran and his team, for they're able for anything to do with boats in any sort of material - I reckon if you wanted to build your dreamship out of resinated peat moss, then Tom would be game for the job.

Can-do people of the west – Mary and Tom Moran of Clew Bay Boats have successfully taken on many marine problems and projects. Photo: W M Nixon

Sorting out the interior systems is going to be more of a challenge, for Hesperia was originally Noryema X, built for Ron Amey in 1975. In a sense, there's a feeling of homecoming in the fact that she's being restored in Westport. If you head directly inland from that lovely little town, you're soon up in the mountains in the Joyce Country. And way back in 1975, the alloy hull of Noryema X was built by the renowned Joyce Brothers. Their fabrication workshop may have been in Southampton, but the family wasn't that long out of the mountains of far Mayo.

However, once the innovative Ron Amey had taken delivery of the hull of his latest Noryema from the brothers Joyce, he then took it to Moody's big shed at Bursledon on the Hamble for completion by the boatyard's craftsmen. I happened to be Bursledon-based in the early summer of 1975, and it really was all a wonder to behold.

Amey had installed a caravan in Moody's shed, and he lived in it while overseeing every detail of the new boat's fitout, while at the same time running his business empire of Amey Roadstone from a telephone in the caravan. It was said that the great man wouldn't be really happy with his new boats until the final jobs were completed just before the Fastnet Race in August, and after that he'd then start to think of the next one. But Noryema X was something special. She became the last of the racing line, and despite her enormous rig, Ron Amey then used her for eleven years of cruising in the Mediterranean which concluded with her sale to Brian Buchanan of Belfast Lough at Marseilles in 1986. She has been based on our island ever since, the source of much seagoing pleasure for hundreds of Irish sailors.

So bringing her back up to Amey standards is quite a challenge, as she's now part of Ireland's sailing heritage. But with Tom Moran they've someone who seems to have links with every maritime specialist in the country, and if he draws a blank in Ireland, his connections around the Solent marine industry seem pretty hot too.

Not quite where you'd expect to find an Arctic voyaging vessel, but Northabout seems at home in the Moylure Canal in the midst off Mayo fields. Photo: W M Nixon

Much encouraged by all this, for Clew Bay Boats is the sort of place where many good things seem possible, we then headed down to the Moylure Canal, a drainage waterway near Rosmoney at the head of Clew Bay where the great Jarlath Cunnane has created a tiny boat harbour and beside it a little place where, if so minded, he can build himself a boat.

Jarlath is the quintessential Connacht mariner, yet you'll never find him being sentimental about wooden boats. On the contrary, in the time I've known him he has built himself a steel van de Stadt 34ft sloop which he cruised very extensively, and more recently he took on the challenge of alloy construction to build the 44ft Northabout. Aboard this special boat, in teamwork with Paddy Barry, he has made cruises to remote and challenging places in voyages which, for most people, would have required full military logistical support.

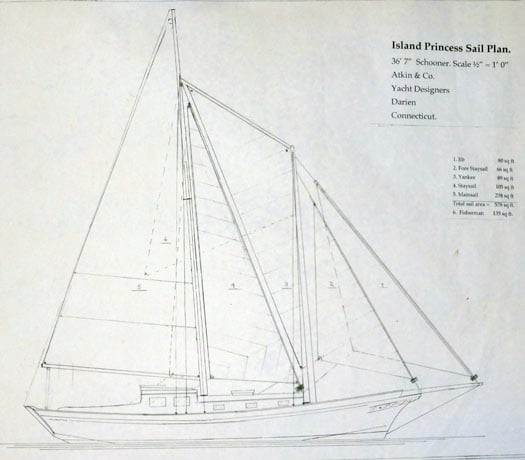

The new dreamship. Plans of the 37ft Atkins schooner which Jarlath Cunnane has been building over four years.

Knowing the scale of what he has done with her, it was bizarre to see Northabout sitting modestly in her berth in the little creek beside a Mayo field. But the presence of the long distance high latitude voyager was only part of the Moylure package. A few feet away in "the shed which isn't really a shed" was the new Cunnane boat, a sweet 37ft–Atkins schooner which, if you haven't yet appreciated the potential of good alloy boat construction, would surely win you over in a trice.

Good alloy construction, as seen here in the stemhead of the new schooner, can withstand comparison with any material. Photo: W M Nixon

The new schooner has a workmanlike and handsome hull......Photo: W M Nixon

....which is aimed for comfort as much as speed, but she should be able to give a good account of herself in performance, and will be very comfortable for longterm periods on board. Photo: W M Nixon

Jarlath has taken four years on the construction, and when he gets to sailing the new boat, I'd say that the motto will be: "When God made time, he made a lot of it". This is a boat for leisurely cruising, a boat to enjoy simply being on board. In her finished state, she'll give little enough in the way of clues as to her basic construction material. Like Killary Flyer, and like Northabout too, she is in her own way a great advertisement for the potential of good alloy construction.

As completion nears, it becomes ever less apparent......Photo: W M Nixon

.....that the hull construction of the new schoner is in aluminium. Photo: W M Nixon

So we'll sign off this week with a special thought. As Irish life begins to move again, doubtless we'll soon hear increasing mutterings about the desirability of building a new Asgard sail training brigantine. Maybe we should keep the government out of it this time round, and build her through a voluntary trust organisation supported by public subscriptions and corporate donations. But however it's to be done, we should be starting to think about it.

And like many others, I've long thought that the ideal way forward would be with a steel hull built to Jack Tyrell's original Asgard II lines, which have a magnificently timeless quality to them. But I've changed my mind on that. Having seen what can be done with good alloy construction down in Mayo, and knowing the quality of alloy workboat construction being produced by firms like Mevagh Boatyard in Donegal and by the descendants of Jack Tyrrell among others at Arklow Marine Services in County Wicklow, it's difficult to escape the conclusion that the hull of the new ship should be built in aluminium.

It would be initially expensive, but it would confer great longterm maintenance advantages. And by going that way, we'd be able to provide all the double skins and safety bulkheads which will now be required without using up all available hull space, and without producing a boat so heavy she wouldn't be able to sail out of her own way. So let's hear it for an aluminium-hulled Asgard III.

#eastcoastports – Ireland's east and north coasts may lack the cruising glamour of the south and western seaboards, but W M Nixon suggests that the ICC's East & North Coast Sailing Directions points the way to an area with its own special charms. And he ponders a coastal mountain-measuring quandary in this blog first published in March 2014.

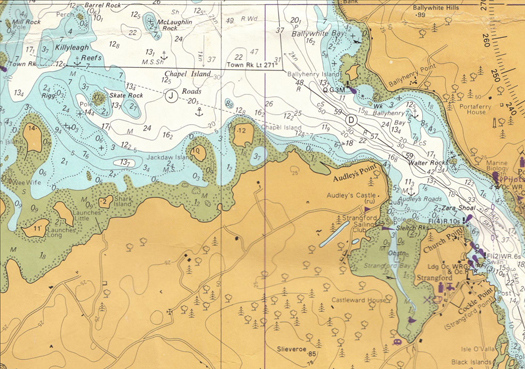

Now here's a thought. Could it be that Scrabo, the tower-topped hill which dominates the northern waters of Strangford Lough, is not as high as officially reckoned? Could it be that its recognised height of 538ft (which doesn't include the 125ft height of the tower itself) is a bit optimistic?

Such notions come from contemplating aspects of the new 12th Edition of the Irish Cruising Club's Sailing Directions for the East & North Coasts of Ireland, which is now on sale at £29.95 or €37.50. It's worth every cent, not just for those planning to cruise the area, but simply if you sail from any of the ports covered. And the interest lies not just in the essential information conveyed for safe navigation and pilotage along these many miles of varied coastline, but also in the implications of that information in a larger context.

As the ICC publishes two books with the most recent massive 13th edition of its best-selling South & West guide appearing last year, inevitably people will compare the two areas. And equally inevitably, the east coast can appear a rather humdrum sort of place by comparison with the lotus-eating charms of the south coast, and the spectacular glories of the west, while the north coast sometimes seems just too challenging to be contemplated at all. However, in one category the east and north coasts put the south and west coasts in the ha'penny place. The eastern and northern seaboards are absolutely tops in tides.

On the west and south coasts, apart from the Shannon Estuary and maybe Achill Sound and perhaps Cork Harbour entrance at Springs, tidal streams are relatively weak on the entire coastline going westabout between Hook Head in Wexford and Bloody Foreland in Donegal. And yes, I too have shot the tidal rapids at Lough Hyne, but that's a special case. Otherwise, it's useful to have the tide with you along the coast, and it's best to avoid wind-over-tide at major headlands. But generally, unless you've a long passage planned you can come and go at sociable hours for day sails rather than having your schedule dictated by tide.

Yet if you're voyaging that same journey from Ireland's southeast corner to the far northwestern extremity via the east and north coasts with the absolute shortest distance being 282 miles, the tidal streams are dictating your times of coming and going except between Skerries and Ardglass on the east coast, and west of Malin Head on the north. Elsewhere, it's conveyor belt coastline, and anyone sensible will go with the flow.

Carlingford Lough is one of several inlets on these coastlines whose narrow entrances have strong tides. The mediaeval little township of Carlingford has its own largely drying harbour (foreground), but the marina further along the shore is accessible at all states of tides, and has facilities on site. However, village waterfront hospitality resources are somewhat spread out, as the hospitable Carlingford Sailing Club (extreme right), with its own slipway and welcoming clubhouse, is at a significant distance from the marina. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

In addition, where natural harbours and sheltered inlets exist, in a surprising number of cases on the east and north coasts the entrances are narrow, and pushing the tide to get through can be a serious challenge. This is the case in Mulroy Bay, Lough Foyle, Larne Lough, Strangford Lough and Carlingford Lough. But the great inlets of the west, particularly the magnificent rias of the southwest, are drowned river valleys which close in only gradually, resulting in much gentler tides.

Strangford Lough's entrance by contrast is totally tide-dominated, and many local cruising boats solve the problem simply by never leaving the place. But as a study of this new book (yet another extraordinary effort from the ICC's remarkable sailing directions team of Norman Kean and Geraldine Hennigan) successfully reveals, Strangford Lough is indeed a wonderful world unto itself, and you could happily cruise here for a week without feeling the need to venture into the dark unknown to seaward beyond The Narrows, where the tides hit 8 knots and more, and the whirlpool of the Routen Wheel waits to trap the unwary.

It's the business of the sea pushing in and out Strangford Lough twice a day (and generating electricity while it does so) which provokes the thought that maybe Scrabo is not as high as generally thought. The hill is simply known as Scrabo, which sounds like somewhere in Transylvania – it could be Dracula's summer residence - but apparently it means nothing more exciting than "cow pasture" in Gaelic. They were hardy cattle in them days, as it can be rugged enough on top, for Scrabo's location relative to the serene inner reaches of Strangford Lough emphasises its exposed nature.

Strangford Narrows, with a smooth yet powerful stream, though it can be anything but smooth when it meets open water and an onshore wind. The tides in the Narrows provide so much guaranteed energy that they have been harnessed by this generator to provide sufficient electricity for a thousand homes. Photo: courtesy ICC

The Seagen tower with its turbines raised clear. Like this, it can be a hazard for sailboats passing too close. Currently, the scorecard reads: Seagen-1, Yacht Masts-0. Miraculously, no-one was hurt. Photo courtesy ICC.

But the point is that high water in those remote inner reaches and in Strangford Lough generally occurs a clear two and a half hours after high water in the Irish Sea. Thus down at the Narrows, the water may be still pouring into the lough, yet out in the Irish Sea the tide has peaked, the ebb is running north, and the sea level has been falling for a good two and a half hours by the time the final surge has reached the top, way up at the flat shore below Scrabo.

So it occurs to me that, could we but somehow measure by the most precise methods exactly from the centre of the earth, then mean sea level at Scrabo would always be less – maybe even a metre less – than on the ocean generally. And for all hills, whether it be Scrabo or Everest or whatever, the height above sea level is the gold standard. So the surface of the sea must curve over and above the curvature of the earth.

My ignorance of modern surveying methods being almost total, doubtless this idle speculation will bring down scorn, and we'll find that crude measures of sea level by observation at a local position have been long since superseded by more scientific techniques. Probably these days sea level has little enough to do with the level of the sea. But if you're someone who likes to muse on such things as the true height of Scrabo in the light of Strangford Lough's wayward tides, then you've the mind of a cruising person, and you'll find the new guide a delight, particularly if you reckon the east coast has been getting a raw deal in the perception stakes.

The Economic Corridor. Dublin Port looking seaward at a quiet period between ship movements, which currently run at 40 per day. Grand Canal basin is bottom right, while the ancient maritime community of Ringsend is just across the River Dodder. The Dodder's east bank, now lined with corporation flats, used to be a hive of activity with at least four boatyards on the foreshore. Poolbeg Y & BC marina is beside Roingsend. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

That said, it has to be admitted that between Dublin and Belfast, the "East Coast Economic Corridor" may sound glamorous to business folk, but it can make it all seem rather workaday to the rest of us when sailing the nearby sea. Then too, the dictation of the tide in setting the times of your passage-making gives a sense that you're commuting along the coast, rather than cruising it. Finally, while there may be several handsome ranges of hills and mountain along both coastlines, only in certain areas is there significant indentation of the coastline to give that air of excited anticipation as to what might be round the next corner. By contrast in the south and west you've many variations on the sense of anticipation exemplified by the always uplifting experience of coming northwards through Dursey Sound and suddenly seeing the entire panorama of the Kerry mountains revealed in all their purple glory.

But living in such a state of constant excited anticipation would be damaging for anyone's health. The real business of life is making the best of the hand you've been dealt, and these days the east and north coast deal is much enhanced by greatly improved harbours and marinas. These make for much more convenient access to port towns, which in their turn provide a better hospitality package which adds greatly to the enjoyment of a day's sail along a coast which may have been looking very well indeed.

Not least of the factors in this is that, along the east coast at any rate, it rains less than on Ireland's other coastlines. Sometimes a lot less. And it's at its best when the wind is the Atlantic breeze, the westerly off the land. When "the wind is off the grass", as the crewmen in the Irish Lights vessel describe their ideal conditions for working at buoys and other navigation aids, then sailing Ireland's east coast is very pleasant indeed.

Although the east coast officially begins at Carnsore Point, the ICC Directions sensibly begin just round the corner at Kilmore Quay, whose transformation by Wexford County Council into a useful sailing/fishing harbour has greatly changed everyone's perception of the area. And just to show that the Saltee Islands can now be seen at the very least as an interesting day cruising destination from Kilmore itself, the book includes a useful photo of the fair weather anchorage on the southeast coast of the Great Saltee.

In times past, the Saltee Islands were seen by cruising folk as somewhere to get past as quickly as possible. But now that there's a fine little all-weather harbour and marina at Kilmore Quay, this photo of the fair weather anchorage off the southeast coast of the Great Saltee is of special interest. Photo courtesy ICC.

Heading up the east coast, the favoured first port of call tends to be Arklow, where developments in recent years have been an intriguing illustration of the way Ireland is administered. In any rational society, you'd have expected the Arklow Basin on the south side of the river – which has the benefit of having an exceptionally small tidal range – to be re-developed as a modern recreational harbour, a sort of Irish Honfleur.

But of course any attempts at this sensible line of action were stymied by inertia and entrenched interests, so the get-up-and-go section of Arklow society simply got on with things on the north side of the river. There, a marina has been developed in a new basin, and what amounts to a new township shows every sign of developing alongside it, while across the river the old basin slumbers on.

Arklow is home to an ancient seafaring tradition, manifested itoday in a vibrant locally-registered merchant fleet which operates internationally. The new harbour and waterfront development on the north bank of the river (left) proceeds crisply ahead while the old Arklow basin on the other side ponders it future. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

Undoubtedly the most exciting development on the east coast in recent years has been the creation of an all-weather harbour at Greystones, within easy sailing distance of Dublin yet just far enough to provide a sense of achievement. And there's a certain extra satisfaction in enjoying your breakfast aboard a cruising boat in the new marina while the commuter-filled DART trains trundle past headed towards the city, yet beyond in the morning sun the Wicklow hills look more beautiful than ever.

"Good morning, Greystones, how are you?" Breakfast on a cruising boat never tastes better than when you're in the new Greystones Marina with the early sun on the Wicklow hills, and a DART train filled with commuters heads for Dublin. Photo courtesy ICC

With the coastal developments of the last twenty to thirty years, the east and north coasts have now been reborn as sailing and cruising areas with the two main yacht harbours at Dun Laoghaire and Bangor, while there are now medium size marinas at Greystones, Poolbeg in Dublin, Howth, Malahide, Carlingford, Carrickfergus, Glenarm, Ballycastle, and Fahan on Lough Swilly.

Additionally there are the key smaller facilities at Arklow, Warrenppoint, Ardglass. Portaferry, Belfast Harbour, Rathlin Island, the Bann Estuary, Derry/Londonderry and Rathmullan, while convenient landing pontoons have been installed at several other sites. Details on all these and much more can be found in the new ICC book, but anyone cruising the region develops fondness for some favourite spot, and as someone who has been cruising up and down these coasts for a while now, I have to say that the facility which has most transformed the cruising is surely the little marina at Ardglass, officially known as Phenick Cove.

Kingpin harbour – Dun Laoghaire before the new "library" was erected at amazing speed in the middle of the waterfront. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

Ardglass. This little port has become one of the most useful of all, particularly for people who really do cruise. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

It is just so conveniently located, you don't have to deviate at all from the direct course up and down Ireland's East Coast, and the welcome provided by marina manager Fred and his array of amiable animals is second to none. Quite how we managed before Ardglass marina was installed I don't know any more. But I think it involved far too many unnecessary nights at sea, whereas now you can have a convenient overnight in a quirky place where – if you're minded to eat ashore – you can ring the changes between one of the best Chinese restaurants on the coast, or else the golf club in the castle makes sailors more than welcome, and if you've had enough of the salty sea for a while, a very short taxi ride takes you into the utterly and very aromatically rural heart of the country and steaks at Curran's foodie pub.

Bangor Bay's marina has settled in so well you could be forgiven for thinking the town was built around it. And you won't be surprised to learn that this part of North Down is known as the Gold Coast. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

When these ICC Directions first appeared in book form in 1946, they covered only the east coast, and that only between Carnsore Point and the little harbour of Carnlough on the Antrim coast. In those days, there were few if any facilities for cruising boats beyond it on the Irish coast, so it was seen as the best jumping-off port for people headed for the more civilised cruising on Scotland's west coast.

Ballycastle Harbour and marina required a king-size breakwater for full shelter, but its convenient location has been greatly beneficial for cruising the area. Photo courtesy ICC/Kevin Dwyer

Thirty years ago, the notion of Rathlin Island as a popular cruising destination would have seemed absurd, yet the provision of a harbour has brought about a welcome change, and in summer there are always at least several (and often many) cruising boats in port. Photo courtesy ICC.