Displaying items by tag: Boat Building

The Boat Building Academy (BBA), based in Lyme Regis, Dorset, is seeking seven committed and enthusiastic individuals to change their lives via its 40-week boat building course.

Starting mid-May, the course will teach skills such as lofting, traditional, modern and fibre reinforced plastic boatbuilding, as well as spar, oar and sailmaking and more.

Students step away with confidence, talent, a wide skill pool and a City & Guilds 2463 Level 3 Diploma in Marine Construction, Systems Engineering and Maintenance (the technical certificate of an apprenticeship).

"We see the next course as perfect for those who have taken a step back during the pandemic and re-thought about what they want to do with their lives," says Will Reed, BBA's Principal/Trustee. "Those individuals who want to work with their hands, who want to learn to craft objects of beauty and who want to pour their hearts and souls into creating truly unique boats."

As well as a select number of school leavers, the academy's boat building courses always attract a mix of students who are changing from careers like the police, finance, and education

As well as a select number of school leavers, the academy's boat building courses always attract a mix of students who are changing from careers like the police, finance, and education

The Boat Building Academy has an impressive alumni career path. It's long been seen as the formative steppingstone into the highly skilled world of high-end boat-building. Many of those who pass through its doors are actively recruited by top UK and international boat builders like Spirit Yachts and T Nielsen’s.

As well as a select number of school leavers, Will says the academy's courses always attract a mix of students who are changing from careers like the police, finance, and education. Others are starting their retirements with a purpose, fulfilling a passion ready for their retirement.

One of these is Graham Pickett, an ex-Deloitte’s partner, who has finally fulfilled his life's ambition of building his own boat.

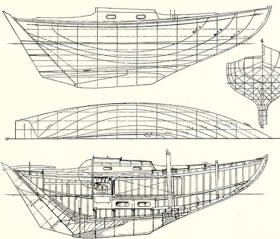

"I built a Yachting World Day Boat," Graham says. "It's glued clinker construction, made out of marine plywood for the planking, with everything else made from sapele and good English oak. I'm going to use it for day sailing with friends who I met at the academy, and I've got an outboard for it so I can go fishing too."

Graham says the skills he gained on the boat building course have helped him significantly in his wider life.

"The expertise I gained has put me in great stead already - I live in a home that needs carpentry and woodworking jobs doing. The whole experience has been exhilarating and challenging, I've learnt so much in the process."

The BBA's academic structure is unique. The academy offers access to the tools and materials out of hours (including weekends), making the course very attractive for those serious about developing their skillset. And, the workshop space is currently being enlarged, thanks in significant part to a recent crowd-funding exercise. This means Will Reed is confident in the provisions the academy has made to ensure all students can work in a covid-secure environment.

The next cohort starts on 17 May, and it's not too late to get involved. The fee (£15,850) includes all tutoring and the vast majority of the materials needed but does not cover the cost of building a boat. The administration department can help with finding rooms. There are nine rooms on site and the academy enjoys a close relationship with a wide network of local houses who have rooms to rent.

Skills covered:

- Lofting

- Traditional boatbuilding

- Modern wooden boatbuilding

- Fibre reinforced plastic boatbuilding and fit out

- Yacht joinery

- Spar and oar making

- Engine beds and stern tubes

- Finishing coatings and compounds

- Rigging, chandlery and cordage

- Sail making and repair

- Marine systems

And, as well as boat building, students spend the 40 weeks learning maintenance and support

"I would recommend this course for anybody," says Graham. "It's got first-rate tutors, a formalised programme, and some of us come out the end of it with a boat and a great qualification. You learn a lot in the process."

Are Traditional Boat Building Skills Disappearing?

Following the interest in last week’s Podcast on the question – Why Do We Own Boats – and the views on the topic expressed by Brother Anthony Keane of Glenstal Abbey, I’ve been intrigued by the number of people who contacted me since, referring to an ancillary issue about owning boats– maintaining and preserving them and difficulties in some areas of finding the necessary skills.

It seems problems are associated with the types of boats needing attention and whether all yards have the skills within their staffs or need to seek it from what appears to be a finite number of people with specialist skills and that shipwrights appear to be a disappearing trade.

I was even told that maritime archaeologists are becoming increasingly interested in working with boat builders to study traditional maritime skills, because of concern that they are disappearing.

There are areas where the skills are being passed on – such as the ILEN boat building school in Limerick and the Hegarty yard at Old Court near Skibbereen, where boat building skills are certainly evident in how the ILEN was reconstructed there. The Meitheal Mara community boatyard in Cork is another area of activity.

The skills of a boatyard in evidence as restored Dublin Bay 21 Naneen is lowered into the water at Kilrush

The skills of a boatyard in evidence as restored Dublin Bay 21 Naneen is lowered into the water at Kilrush

There are courses in boat building offered at Third Level Institutes and voluntarily by sailing and boat clubs, but the passing on of skills and recruitment of apprentices does seem to be an issue. When there is a special boat project underway it can attract a lot of public attention which can feed into an awakening of interest in the skills. That point was made to me by Steve Morris who led the revival of the Dublin Bay 21 Naneen at Kilrush Boatyard in County Clare. When she was launched, he told me that the project would leave behind interest in the skills and referred to the problems which Afloat readers and Podcast listeners have identified.

Listen to Steve Morris on the Podcast below

Historic Ketch Ilen’s Busy Workshop in Limerick Keeps the Baltimore Show on the Road

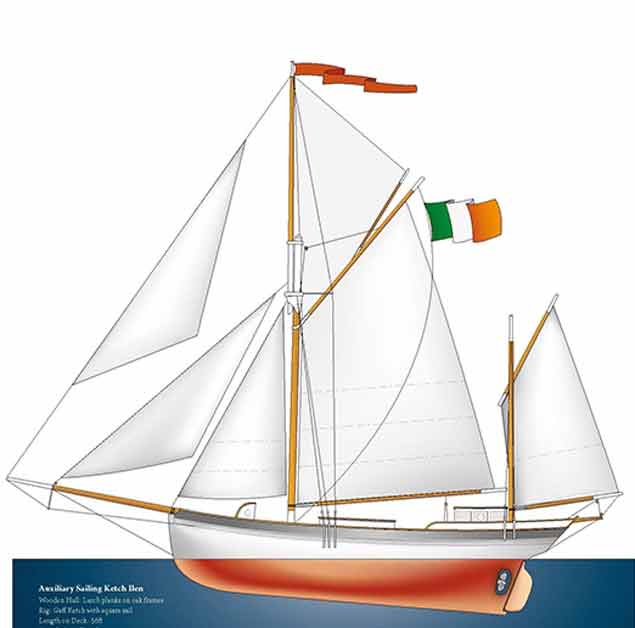

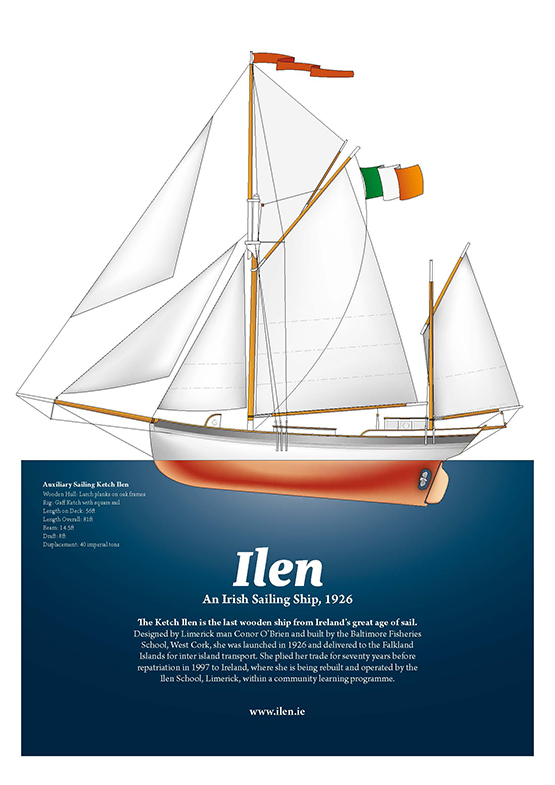

Many people have dropped by the Old Cornstore on the riverside at Oldcourt in West Cork to see work progressing on the restoration of the 1926 Conor O’Brien ketch Ilen writes WM Nixon. And naturally they’ll have the impression that they’re at the main scene of the action. After all, the 56ft vessel certainly looks the part - a complete ship, full of promise in her distinctive new colour scheme.

But as Gary MacMahon of the Ilen Boatbuilding School in Limerick points out, even with a hefty traditional vessel like Ilen, the finished hull with deck in place is only about 35% of the complete and fully commissioned vessel. And though the assembly of the various parts inevitably has to take place in Oldcourt with Liam Hegarty and his team, much of what you’re looking at on the Ilen today was actually built in the Ilen School’s efficient workshops in Limerick city.

The Ilen herself in Oldcourt near Baltimore, newly painted and looking very well. Photo Ilen BS

The Ilen herself in Oldcourt near Baltimore, newly painted and looking very well. Photo Ilen BS

The new deckhouses, hatches etc on the Ilen were all made in Limerick. Photo Ilen BS

The new deckhouses, hatches etc on the Ilen were all made in Limerick. Photo Ilen BS

There, young people – indeed, people of all ages and from many backgrounds – are finding that working with wood, and creating parts for boats or building complete boats, is a profoundly interesting and fulfilling experience. In recent years, the Ilen School has turned out impressively authentic versions of the traditional Shannon gandelow, and in a completely different direction, sailing dinghies of the distinctive CityOne class to a very special design by the late Theo Rye.

One of the Ilen Boatbuilding School’s traditional gandelows on the Shannon in Limerick, heading upriver towards King John’s Castle. Photo: Gary MacMahon

One of the Ilen Boatbuilding School’s traditional gandelows on the Shannon in Limerick, heading upriver towards King John’s Castle. Photo: Gary MacMahon

It makes a change from the Shannon Estuary - the Ilen Boatbuilding School’s gandelows in Venice. Photos: Gary MacMahon

It makes a change from the Shannon Estuary - the Ilen Boatbuilding School’s gandelows in Venice. Photos: Gary MacMahon

These smaller craft have been imaginatively used by those who built them for various expeditions to events such as the Baltimore Woodenboat Festival and the Glandore Classics Regatta. And in 2014, the Gandelows somehow managed a remarkable double by taking part in the Thousandth Anniversary re-enactment of the Battle of Clontarf (wasn’t Brian Boru a Limerick man, after all?) and yet somehow also took in a Marine Festival in Venice, as it’s reckoned that the word “gandelow” originated from gondola, but mutated along the way.

Having taken such things and various other projects in their stride, the Ilen people in Limerick have enthusiastically lined up to build the deckhouses, hatchways, skylights, lignum vitae rigging deadeyes and many other items for Ilen herself. Each is an exquisite bit of marine joinerywork in its own right, and when fitted on the ship, they go so well with the overall concept that you’d be hard-pressed to guess that they were built many miles away, in the characterful city on Shannonside, rather than among the rolling green hills and woodland of West Cork.

Deadeyes made in Limerick from rare lignum vitae – the word is that this very high density wood “was sourced from a former shipyard in Cork”. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Deadeyes made in Limerick from rare lignum vitae – the word is that this very high density wood “was sourced from a former shipyard in Cork”. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Group discussion in Limerick with Liam, Trevor, Pete and Robert to sort and assess items of rigging gear. Photos: Gary MacMahon

Group discussion in Limerick with Liam, Trevor, Pete and Robert to sort and assess items of rigging gear. Photos: Gary MacMahon

Modern safety requirements dictate that the original guard-rail stanchions (left) have to be replaced by longer ones (right) to provide one metre clearance. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Modern safety requirements dictate that the original guard-rail stanchions (left) have to be replaced by longer ones (right) to provide one metre clearance. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The hydraulic steering actuator is cleaned and serviced before being sent for pressure testing. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The hydraulic steering actuator is cleaned and serviced before being sent for pressure testing. Photo: Gary MacMahon

But such is the case, because for all his fondness for West Cork, Conor O’Brien’s spirit is in Foynes Island on the Shannon Estuary, and Limerick is his city, the city of the O’Briens since time immemorial. And recently, Limerick has been turning out the stanchions for the Ilen’s guard-rails, something which is well in line with the city’s engineering traditions. But most impressive of all is the final work on finishing the spars.

When Ilen was shipped back from the Falklands in 1998, some of her surviving spars were in a decidedly poor conditions. But the new Limerick-built replacements are robust works of art, with a natural functional beauty. It really will be a show on the road, and then some, when they’re taken on that winding journey from Limerick down to Baltimore.

An authentic marine bronze Kobelt heavy duty engine control is sourced “by good fortune” – it cleans up a treat

An authentic marine bronze Kobelt heavy duty engine control is sourced “by good fortune” – it cleans up a treat

Finally getting there – Liam O’Donoghue gives Ilen’s new mainmast its finishing coats of paint – the special colour is “US Navy buff” Photo: Gary MacMahon

Finally getting there – Liam O’Donoghue gives Ilen’s new mainmast its finishing coats of paint – the special colour is “US Navy buff” Photo: Gary MacMahon

Alchemy Marine Will Work Magic to Re–Create Cork Harbour Classic Boat of 65 Years Ago

Bill Trafford of Alchemy Marine, hidden away in the farmland of Skenakilla west of Mitchellstown in north County Cork, has carved himself a unique reputation in recent years for successfully re-imagining glassfibre boats of a certain age, and transforming them into modern classics writes W M Nixon.

In fact, calling them “boats” at a key stage of this process is scarcely accurate. What arrives in his shed as a former but still recognisably standard sailing craft quickly becomes no more than “the donor boat”, which is soon a bare hull with which Bill is free to play, re-tweaking the sheerline, altering the stern, and adding a completely new deck and coachroof configuration

That’s just for starters. But with the former Elizabethan 23 Kioni, and more recently the former Etchells 22 Guapa, the process is indeed magic, because both boats have ultimately emerged as beautiful head-turners wherever they sail.

The beautiful Kioni was created from a lengthened Elizabethan 23 glassfibre hull. But now Bill Trafford plans to re-create the spirit of the Colleen by shortening an Elizabethan 29 hull

The beautiful Kioni was created from a lengthened Elizabethan 23 glassfibre hull. But now Bill Trafford plans to re-create the spirit of the Colleen by shortening an Elizabethan 29 hull

But while he was given a lot of freedom in making choices with those boats, Bill’s main project this winter is for a very specific project.

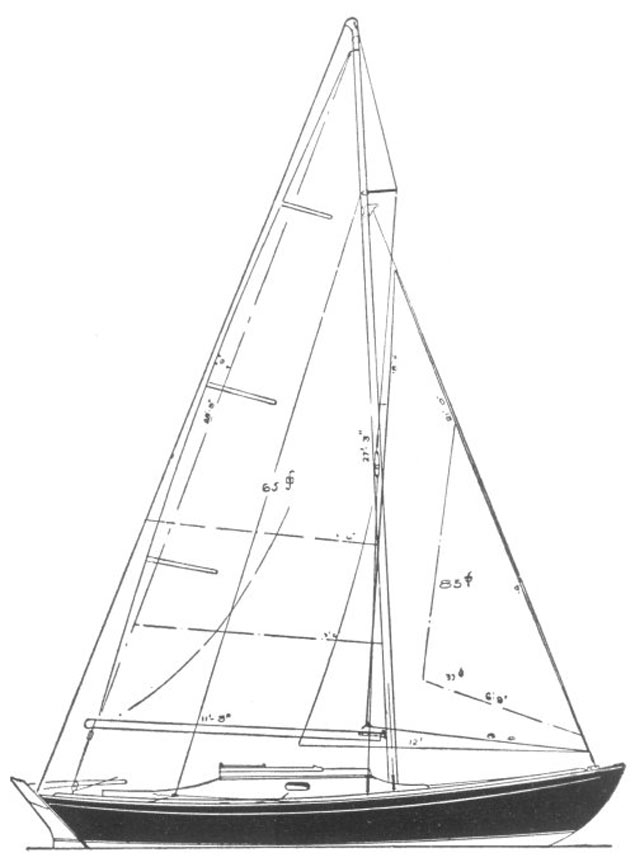

Back in 1950, some members of the Royal Cork YC commissioned a boat from up-and-coming yacht designer Alan Buchanan. They wanted a miniature yet classically stylish performance cruiser, just 23ft 2ins LOA, to be called the Colleen and capable of being built locally.

The 1950s were very far from being a boom time in Ireland, so it seems that no more than four were built. But one or two are still about, and a contemporary Cork Harbour sailor fancies the look of them, but doesn’t fancy the hassle of maintaining a wooden hull.

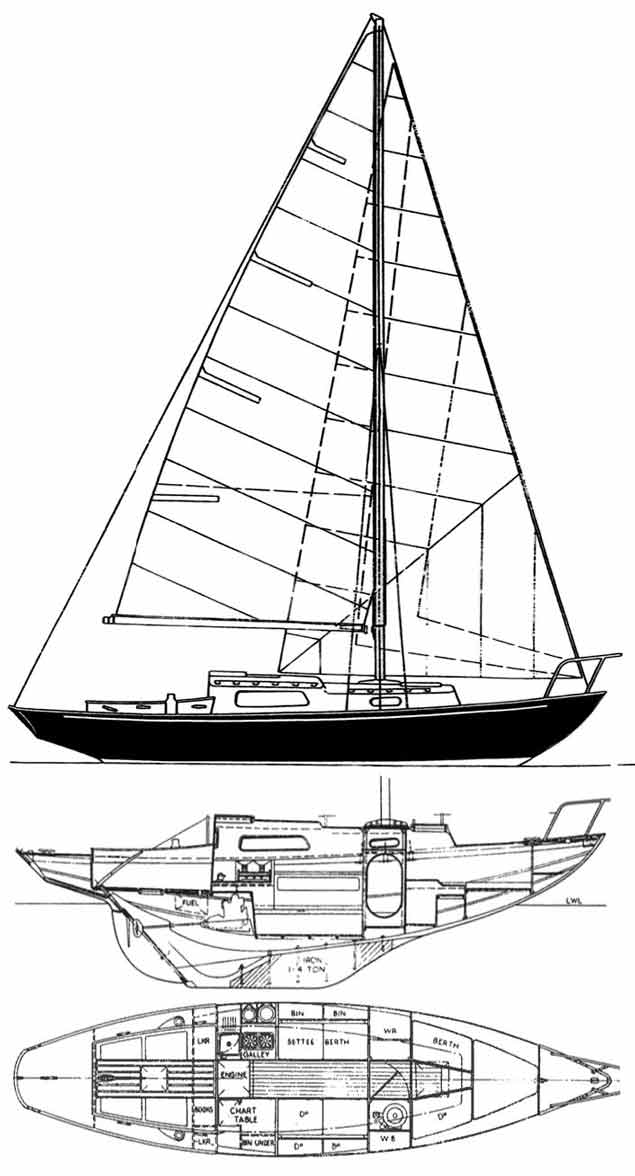

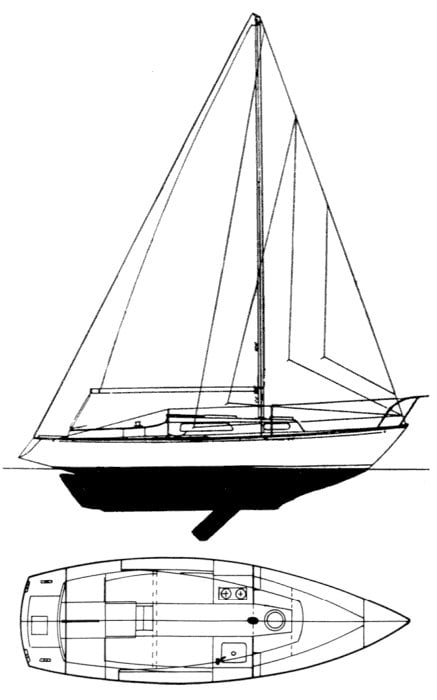

So now Bill Trafford faces the challenge of creating a new Colleen from a glassfibre hull donated by some other boat. He quickly realised that the Buchanan-designed glassfibre Halcyon 27 – which has a transom stern – was otherwise unsuitable, so he settled on the Elizabethan 29, designed by Kim Holman and built with great success by Peter Webster in Lymington in the 1950s.

The original Colleen profile. While the spirit of the boat will be re-captured, it’s possible the very vigorous sheerling will be slightly softened by moving the lowest point a little bit further aft

The original Colleen profile. While the spirit of the boat will be re-captured, it’s possible the very vigorous sheerling will be slightly softened by moving the lowest point a little bit further aft The Elizabethan 29 in unaltered form – it takes Bill Trafford’s vision to see a Colleen in there somewhere

The Elizabethan 29 in unaltered form – it takes Bill Trafford’s vision to see a Colleen in there somewhere

He found one in giveaway terms on ebay in the middle of England at Milton Keynes, and Jonathan Kennedy of Kennedy Boat Haulage personally undertook the long trek to move the little boat from a neglected condition in the middle of England to a winter of transformation in the middle of Munster.

Having seen what Bill Trafford has been able to do with a former Elizabethan 23 and a former Etchells 22, there’s no need to doubt that the spirit of the Colleen will be re-captured in that secret laboratory near Skenakilla Cross-roads. And those of us who feel that the vigorous sheerline of the original might have been better if it had the lowest point slightly further aft may even be indulged in our views. But that of course is up to the owner, who has greatly brightened the prospects of the winter by commissioning this fascinating project

The donor hull of the Elizabethan 29 arrived in the yard, awaiting a miraculous transformation. Photo: Bill Trafford

The donor hull of the Elizabethan 29 arrived in the yard, awaiting a miraculous transformation. Photo: Bill Trafford

Restored Historic Ketch Ilen Starts to Get Authentic Rigging Through In-House Production

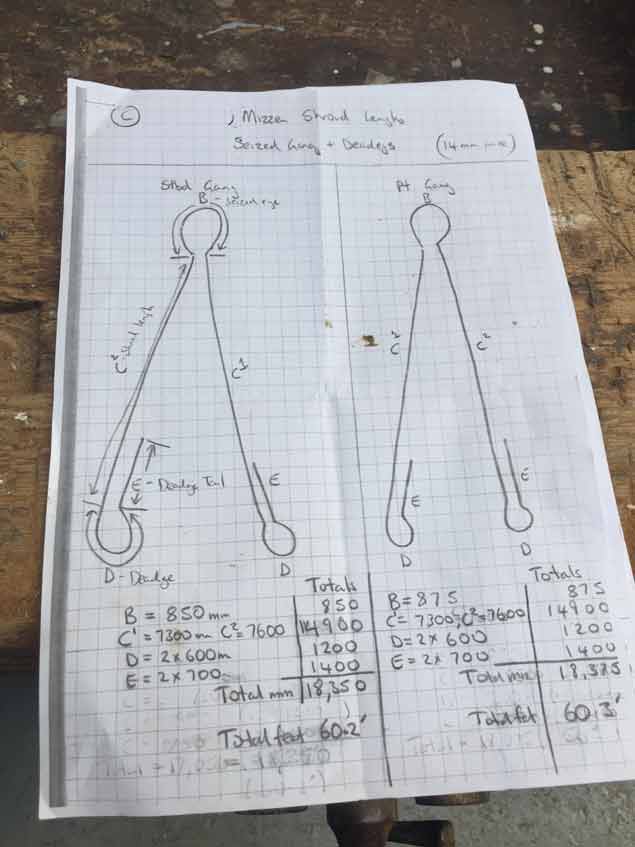

When the restoration project on the 1926-built 56ft Conor O’Brien/Tom Moynihan Falkland Islands Trading Ketch got under way at two locations – Liam Hegarty’s boat-building shed in the former Cornstore at Oldcourt near Baltimore, and the Ilen Boat-building School premises in Limerick – it was expected that final jobs such as making up the rigging and creating the sails would be contracted out to specialists writes W M Nixon.

But while the plan is still in place to have the sails made in traditional style by specialist sailmakers, Gary MacMahon and his team in the Ilen Boat-building School came to the realisation that they’d made so many international contacts over the years while the restoration has been under way that, if they could just get the right people’s schedules to harmonise, then they could learn how to make up the rigging in their own workshops as part of the broader training programme.

Conor O’Brien in 1926, when he delivered Ilen to the Falklands. He had received the order for the new ketch as a result of his visit to the Falkland Islands during his round the world voyage with the 42ft ketch Saoirse in 1923-25

Conor O’Brien in 1926, when he delivered Ilen to the Falklands. He had received the order for the new ketch as a result of his visit to the Falkland Islands during his round the world voyage with the 42ft ketch Saoirse in 1923-25

As a result, the Ilen Boat-building School became a hive of activity over the Bank Holiday Weekend and beyond, for that was the only time when noted heavy rigging experts Trevor Ross, who is originally from New Zealand, and Captain Piers Alvarez, master of the 45-metre barque-rigged tall ship Kaskelot, were both available to make their voluntary instructional contributions to the project.

Trevor Ross with a new eye splice in the Ilen Boat-building School in Limerick. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Trevor Ross with a new eye splice in the Ilen Boat-building School in Limerick. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The re-creation of Ilen’s rig, as developed by Trevor Ross with the late Theo Rye

The re-creation of Ilen’s rig, as developed by Trevor Ross with the late Theo Rye

Trevor Ross was professionally at sea for ten years, during which time he became fascinated with traditional rigging techniques. Though he now works ashore, his interest in traditional rigging and sail training is greater than ever - so much so that he worked with the late Theo Rye in finalizing the design of Ilen’s rig to match the original from Conor O’Brien’s day, while ensuring that it is practical in modern terms both for requirements of efficiency and safety.

Captain Piers Alvarez’s current command is the 45-metre barque Kaskelot

Captain Piers Alvarez’s current command is the 45-metre barque Kaskelot

Piers Alvarez grew up in English cider country near the broad River Severn, but his personal horizons were far beyond apple growing. When he was 15, the captain of the famous square rigger Soren Larsen came to live in the village, which gave Piers’ father the opportunity to sign on his restless son as an Able Seaman at least for the duration of the school holidays, but the boy became hooked on the sea.

More than thirty years later, the love of seafaring and traditional ships is undimmed. Although Piers’ maritime career has also taken in tugs, superyachts and ice-classed research vessels, his current role in command of the Kaskelot perfectly chimes with his most passionate interests, and he has been fascinated by the entire Ilen project from an early stage.

So when the possibility arose of spending time in Limerick working along with his old shipmate Trevor Ross on the rigging for Ilen as a training project for the Ilen School’s intake, he readily gave up a week of his leave to teach the Ilen’s build team and future crew everything he knows, while moving a key part of the Ilen plan along the path of progress.

Piers Alvarez and trainee Elan Broadly busy with their work in Limerick

Piers Alvarez and trainee Elan Broadly busy with their work in Limerick

Ilen School Instructor James Madigan (left) with Piers Alvarez and Elan Broadly, immersed in their learning work while everyone else is on holiday. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Ilen School Instructor James Madigan (left) with Piers Alvarez and Elan Broadly, immersed in their learning work while everyone else is on holiday. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Team work. (Left to right) Liam O’Donoghue, James Madigan, and Elan Broadly on a steep learning curve with Piers Alvarez. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Team work. (Left to right) Liam O’Donoghue, James Madigan, and Elan Broadly on a steep learning curve with Piers Alvarez. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Modern amateur sailors, accustomed to today’s rigging where a terminal can be fitted in a seemingly-simple machine with the press of a button, can scarcely imagine the patient effort and skill which goes into making an eye splice in wire rigging which is of such a weight that, to most of us, it looks more like working with steel hawsers.

This is hard graft, but very rewarding in the result, and the satisfaction found in the effort expended. Much of it is done entirely by hand, but now and again that lethal multiple tool, the angle-grinder, will speed up a finishing job.

Some of the tools used in setting up traditional rigging are of very ancient origin…………….Photo: Gary MacMahon

Some of the tools used in setting up traditional rigging are of very ancient origin…………….Photo: Gary MacMahon

….but inevitably an angle grinder will be used at some stage, and Piers Alvarez is ace with it. Photo: Gary MacMahon

….but inevitably an angle grinder will be used at some stage, and Piers Alvarez is ace with it. Photo: Gary MacMahon

When finished, the neatly parcelled eye-spliced shrouds will fit the re-shaped mast like a glove, while at the other end, the shrouds will be tensioned by traditional lanyards through dead-eyes which have been made in Limerick from tough greenheart timber. It’s a long way from a drum of raw steel wire and a still squared hounds area to be progressed into something which will function on the massive mast in smooth partnership, providing Ilen with her sailing power. And in Limerick over the holiday week, it provided an unusually satisfying way to learn something new and useful.

With the simplest of work drawings, an experienced rigger can turn a piece of hefty steel wire into a serviceable piece of rigging. Photo: Gary MacMahon

With the simplest of work drawings, an experienced rigger can turn a piece of hefty steel wire into a serviceable piece of rigging. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The thick steel wire in its raw state is a daunting sight. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The thick steel wire in its raw state is a daunting sight. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The lower ends of the shrouds will be attached to the chainplates by lanyards rove through deadeyes made from greenheart, seen here at an early stage of the shaping process in Limerick. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The lower ends of the shrouds will be attached to the chainplates by lanyards rove through deadeyes made from greenheart, seen here at an early stage of the shaping process in Limerick. Photo: Gary MacMahon

“Series production” of dead-eyes. Photo: Gary MacMahon

“Series production” of dead-eyes. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Dead-eyes at the final stage of their creation. All that remains to be done is to shape grooves to allow a fair downward lead for the lanyards. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Dead-eyes at the final stage of their creation. All that remains to be done is to shape grooves to allow a fair downward lead for the lanyards. Photo: Gary MacMahon

New Traditional Rig for the Good Ship Ilen

An international gathering at the Ilen School, Roxboro, Limerick of expert marine traditional riggers, sailmakers and classic boatbuilders, might induce one to speculate that a sailing ship is somewhere in Ireland nearing completion. And yes, this gathering of last Friday, clearly marks a significant juncture in the rebuild of Ireland’s 1926 wooden sailing ship Ilen. The way has now been mapped, essential tasks identified, and if rebuilding milestones are achieving, then there is no reason to think that the good ship will not be plying a new trade in Education of the Sea by late summer 2016.

Traditional Boatbuilders Of Historic Milk Harbour On Sligo Coast Provide Fascinating Lecture Topic

One of Ireland’s leading traditional boat authorities, Dr Criostoir Mac Carthaigh, editor of the monumental and authoritative Traditional Boats of Ireland (Collins Press 2008), is giving the Sligo Field Club’s monthly lecture on Friday November 20th. His topic will be the specialised skills and unique traditions of the boat-building and seafaring McCann family of the ancient natural port of Milk Harbour.

At Milk Harbour, which is the sheltered water behind Dernish Island on the sandy north Sligo coast midway between Grange and Cliffoney, the McCanns built – and continue to build, with Johnny and Tom McCann now at the heart of the business - boats for customers from a wide area, and the family are also noted for their ability to sail their boats in the exposed waters of the greater Donegal Bay area.

One of the more intriguing aspects of their work is that they may have been the most southerly constructors of clinker-built craft on Ireland’s west coast, so much so that anyone from Mayo or Galway who decided on clinker construction would have to make his way north to Milk Harbour.

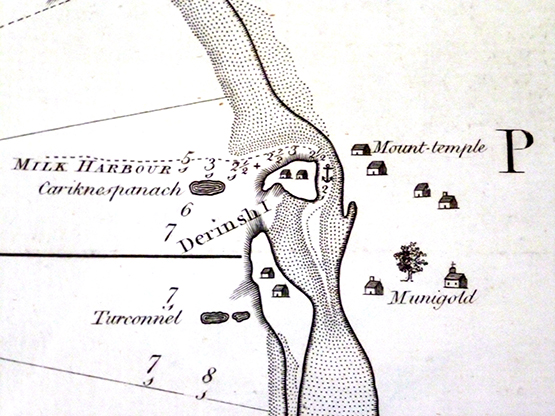

Until proper piers were constructed at places like nearby Mullaghmore, Milk Harbour was the main trading port on the long stretch of exposed coastline between Sligo and Ballyshannon, and its importance was such that in 1776 the noted Scottish cartographer and master mariner Murdock McKenzie included a detailed plan of the entrance to Milk Harbour in his chart of the Donegal Bay area.

Milk Harbour as surveyed by Murdock McKenzie in 1776 – definitey not to be used for navigation in 2015……

The first noted seafaring McCann in the area was Johnny Rua McCann who, in the early 19th Century, made his living carrying cargo in his 28ft yawl from Killybegs to tiny ports on the Donegal and Sligo coasts. One of these was Milk Harbour – also known as Milk Haven - and it was there that the McCann clan eventually established their permanent base and set up a boat-building operation which continues to the present day.

And although Milk Harbour may have conceded the leading local harbour role to Mullaghmore, the place itself is a charming away-from-it-all spot with an anchorage much appreciated by discerning cruising visitors and locals alike.

The Lecture is at the Sligo Education Centre in the Institute of Technology Campus, Sligo, at 8.0pm on Friday November 20th. Any queries to Paul J Allen, Hon. Sec. Sligo Field Club, tel 085-7561024

Criostoir Mac Carthaigh at Kilrush aboard the “re-created” Shannon Hooker Sally O’Keeffe, ne of the many traditional Irish boat projects in which he has been involved. Photo: W M Nixon

Ireland’s Individuality In Boats Is Our Answer To The World’s Uniformity

Located on the fringes of Europe and set in challenging seas, Ireland does not offer an ideal setup for large-output series-production of recreational boats. We lack the economies of scale which are conferred on giant production companies in the crowded heartlands of Europe. There, the ready potential of a vibrant and easily-accessed market is allied with the availability of skilled workforces which are prepared to undertake the tasks in regimented and regulated settings. While these modern production plants may provide bright and well-ventilated conditions, nevertheless they’re markedly industrial in tone and style, and maybe not really in tune with much of life in our own highly individualistic island. W M Nixon takes a look at some of the stories of boat-building in Ireland, and reckons from current experience that specialized work is what we do best.

Despite the less-than-ideal conditions, over the years enthusiasts have given the Irish production fiberglass boat-building challenge their best shots. The continuing and much-enjoyed presence of boats of the Shipman 28 class at many of our sailing centres is a reminder that once upon a time, from the 1970s onwards in Limerick, there was a company called Fibreman Marine, later Fastnet Marine, which built the Swedish-designed Shipman 28 and then expanded the range to include the Fastnet 24, designed by Finot of France.

At much the same time, the Brown brothers were building the Ruffian range – of which the most popular was the Ruffian 23 – in their home town of Portaferry on Strangford Lough, while across the Lough at Killyleagh, Chris Boyd – who’d actually built the first Puppeteer 22s in Larne – set up shop a couple of years later in a new mini-factory and Puppeteers of several sizes rolled off the line.

Meanwhile on the shores of Cork Harbour, a popular range of variations on the Ron Holland Shamrock Half Ton design kept a harbour-side production plant busy for some years. And out west in Tralee, O’Sullivans Marine found themselves some decades ago in the forefront of design development with a new GRP National 18 built around the enthusiasm of the Cork Harbour fleet, and then they went on to build large numbers of the Tony Castro-designed 1720 Sportsboat. But having started as builders of smaller craft with a useful range of elegant lakeboats, they find that the lakeboat is what keeps them going today – it’s a case of going with the knitting while keeping well clear of more high-powered production temptations.

Other pioneers in Irish series boat-building have stayed in the marine business, but have moved their focus. How many know now that our very own marine conglomerate, BJ Marine with its wide boat-oriented interests at home and abroad, started life as a boat-building company with a range of van de Stadt GRP hulls, and then continued as the builder of the Ruffian 23?

God be with the days…..seventy Tralee-built 1720s racing at Cork Week 2000, with Mark Mansfield the winner and Anthony O’Leary second. Photo: Robert Bateman

God be with the days…..seventy Tralee-built 1720s racing at Cork Week 2000, with Mark Mansfield the winner and Anthony O’Leary second. Photo: Robert Bateman

Shipman 28s racing in Dublin Bay. They were built in Limerick in one of several factories in Europe which between them produced 1300 of these boats. Photo: Courtesy VDLR

Shipman 28s racing in Dublin Bay. They were built in Limerick in one of several factories in Europe which between them produced 1300 of these boats. Photo: Courtesy VDLR

Ruffian 23s in Dun Laoghaire Harbour. Originally built in Portaferry to be a Belfast Lough class, at their height they were raced at about ten centres including Hong Kong, but now their most resilient strongholds are Dun Laoghaire and Carrickfergus.

Indeed the story of BJ Marine is in many ways the story of the Irish marine industry, for as the late Dickie Brown of Ruffian fame said of the glory days of their little firm of Weatherly Yachts: “We were the right people in the right place at the right time in the rapidly developing international marine industry. But later, there was no way a little local firm could hope to compete with the giants of the industry in the production of what was, in effect, the sailing equivalent of the small family car.”

It wasn’t just on the coast that semi-production boatbuilders were thriving - or at least surviving - at this particular stage of the Irish marine industry’s development. On the inland waterways, particularly around Carrick-on-Shannon there were firms of all sorts, mainly building motor-cruisers, but as well the great pioneer, O’Brien Kennedy, having come home to build Shannon cruisers, then returned to his first love of sailing boats and created the Kerry 6-tonner, characterfully built in GRP of simulated clinker construction, and still much-loved even if Kennedy International Boats is a long-gone memory.

But since the heady days of the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, several economic storms and revolutions in production methods and materials have blown away much of the Irish marine manufacturing and boat-building industry. The crazy years of the Celtic Tiger only emphasized its demise, as the great waves of new boats joining the Irish fleet were almost entirely imported, while the concurrent property boom meant that even the humblest waterfront boatyard provided other-use high-end development potential which so quickly pushed prices through the roof that anyone who wanted to work at or build boats had to think in terms of finding premises just about as far as they could be from desirable waterside facilities, for that was all that could be afforded.

And yet, some companies have come through. Red Bay Boats in County Antrim started in 1977 as builders of standard little angling craft, but they soon saw the potential of RIBs, and now they’re world leaders. Having introduced a completely new kind of fast powerboat day cruising with their impressive range of multi-function RIBs, they soon realized that today’s people in a hurry want a complete package. So in Cushendall, Red Bay Boats will provide shore storage for your boat when you’re not using it, yet when you carve out one of those short-break holidays which are the way we live today, they’ll have your boat ready and waiting for instant launching, and off you go for a high speed cruise among the Scottish Hebrides – they’ll even organise cruises-in-company.

Across Northern Ireland on Lough Erne, the Leonard family of Carrybridge have taken over Westwood Marine from its production facility in England, and since 2013 have been re-establishing the production line in ideal premises – a former aircraft hangar at the lakeside St Angelo Airport on the Enniskillen-Kesh road. Westwood’s designer is the versatile Andrew Wolstenholme, whose astonishing variety of craft includes the hefty steel 57ft cruising barge-style yacht Ida for Tom & Dee Bailey of Lough Derg. It was a designer-client relationship which was remarkably fruitful, as the only real stumbling block was Dee’s insistence that the boat include a really good full size hot press - it took some time for the very English designer to grasp that she meant an airing cupboard.

One example of Wolstenholme design – the 57ft barge yacht Ida (Tom & Dee Bailey) on Loug Derg. Photo: Noel Griffin

A very different example of Wolstenholme design – the Westwood A405 is now being built in Enniskillen.

For Westwood in their new Enniskillen base, Wolstenholme has been showing his skills in contemporary design with a complete revamp of materials used in the interior, but by any standards the Westwood A405 is a handsome modern craft, and anyone buying a new one from Enniskillen has the bonus of a year’s free berthing on Lough Erne.

Down at the other end of the country, adverse conditions is what keeps Safehaven Marine going strong. Everyone will be familiar with the dramatic videos of their pilot and patrol boats leaping abut like happy porpoises in the breaking water at the entrance to Cork Harbour when there’s a storm force southerly against the spring ebb. But by contrast, a visit to their production facility in Youghal is a soothing experience (once the enormous guard dog has accepted you’re a temporary part of the team), as it’s a sort of mini-cathedral of boat-building where craft capable of taking anything the sea can throw at them are built with meticulous attention in which the only noise comes when the vast extractor fans are activated. Building boats in modern plastics is inevitably a dusty business, and anyone who has worked at it will be fully appreciative of what Frank Kowalski has installed in Safehaven to keep the busy place dust-free.

However, having a setup like this implies the building of high ticket boats in which expense is virtually no object if it can be guaranteed that they’ll fulfill their very special purposes. But for the vast majority of specialist boatbuilders – both professional, semi-professional, and amateur – it’s a case of making do as best you can, and often you’ll find rather special boat being built in unlikely places, often to the extent that the locals don’t known what’s going on, for in some cases they’ll barely know what a boat is in the first place.

From time to time we’ve given away snippets of information abut Jarlath Cunnane’s new 37ft alloy Atkins ketch which he has been building himself in a very hidden little shed beside a drainage canal on Clew Bay. Jarlath of course built the ice-voyaging Northabout - also in alloy - with Paddy Barry and circled the Arctic Circle with the project completed in 2005. But now that the likes of top Chinese skipper Guo Chuan are breezing their way through the Northeast passage in a giant trimaran in a fast sail of a couple of weeks, Jarlath has moved on. Northabout has been sold to be a expedition vessel in Antarctica (her last Irish port was Kilrush in May) – and the new schooner Island Princess is handling a treat, and moving at leisure among the islands of Connacht, while the hidden shed is given over to other business.

Jarlath Cunnane’s new Island Princess is just about as different as possible from his previous expedition boat Northabout except that she too is built in alloy.

Jarlath Cunnane’s new Island Princess is just about as different as possible from his previous expedition boat Northabout except that she too is built in alloy.

But deep in the heart of north county Cork, just about midway between Cork Harbour and Limerick, there’s a fine shed ready and waiting for the next bit of business. And the more unusual your requirements, the more interested Bill Trafford will be in doing it at Alchemy Marine, where he successfully completes boat projects which are so far off the wall that they’re over the hills and well into the next county.

Those of us who are into interesting boats will know that the most dangerous road in Ireland is the one from Carrigaline to Crosshaven, for the further along it you get, the more boats you will see moored in and around Drake’s Pool. They’re a briefly-glimpsed eclectic collection of boats of all ages, shapes and sizes, which means you’re constantly trying to see them while supposedly driving the car at the same time, which is not a good idea at all.

But back in August, the road along the north side of Crookhaven in far west Cork also became a Highway of Hazard. I always have a soft spot for any boats with the good sense to moor on the north side of Crookhaven, for although you’re not even half a mile from the much more fashionable and crowded anchorage off the village, you’re out of the tide. When the flood is making against a stonking westerly, the village anchorage is irritatingly uncomfortable, but a quick move, dropping the visitor’s mooring off the village, and then deploying our oversize windlass and ground tackle at the press of a button over to the north, and Bob’s you uncle, dinner can continue in total serenity.

So anyway one evening last August we were trundling eastward along the road looking favourably on the little group moored in towards Rock Island, and there among them was this heart-stoppingly beautiful little dark blue sloop which looked so much of a piece that I assumed she must be one of those incredibly pricey little semi-customised dayboats which top-end American builders up in Maine might occasionally produce at enormous expense, and even then only for very favoured customers.

Couldn’t have got it more wrong. Turns out she’s a completely re-booted Elizabethan 23 which Bill Trafford of Alchemy Marine up near Doneraile had been hoping to have re-crafted for a discerning owner from Crookhaven Harbour Sailing Club in time to make her debut at the Glandore Classics in July. But you can’t rush the final stages of a job like this for something so vulgar as a deadline, so Kioni quietly made her debut in West Cork in August, and she is simply amazing.

The Trafford speciality is seeing unexpected potential in glassfibre hulls of a certain age, for what he’s looking for is boats that look like yachts, with proper curved garboards and an encapsulated lead ballast keels. We now know that good glassfibre can last for ever, but in many cases the finish didn’t do justice to the superb materials in the original hull. But with more than a bit of tweaking, a beautiful butterfly can emerge from a very ordinary chrysalis.

Not that the Elizabethan 23 wasn’t something quite special in her day, which was 1969. Boatbuilder Peter Webster of Lymington was originally a baker in Yorshire, but he only wanted to builld boats, and he knew Lymington in Hampshire was the place to do it, and having a marina there – Lymington Yacht Haven – would provide the cash flow to support the boat-building. He started with the ground-breaking GRP Elizabethan 29 designed by Kim Holman, which set herself on the high road to success with major wins in Cowes Week and the Round the Island Race. But then Webster got some notions for a centreboard 23-footer, for which he sketched out rough drawings and then persuaded up-and-coming Welsh yacht designer David Thomas to put manners on them, with the result being the pretty-enough Elizabethan 23.

The original design for the Elizabethan 23 had this reasonably conservative coachroof…

The original design for the Elizabethan 23 had this reasonably conservative coachroof…

First big job is to remove deck and coachroof, revealing a rather nice hull underneath

The duo’s most successful combined effort was the Elizabethan 30, which did well in Half Ton racing and was a superb little cruiser-racer generally, so much so that Webster’s pet boat was the bright red Elizabethan 30 Liz of Lymington which he sailed to the end of his days, and then left in his will to David Thomas, who then did the same, and he died well advanced in years last winter.

But meanwhile the mouldings for the Elizabethan 23 had been taken over by another builder who reckoned the enlargement of the coachroof was the only way to go, and it was in one of these boats with its Acropolis on top that Bill Trafford saw the potential to provide a sweet little 26ft day-boat, though with a couple of bunks, a proper sea toilet, and an inboard diesel, for the clear-headed Crookhaven Harbour sailor.

They defined lines of negotiation between what Bill wanted to do, and what the owner required, and work proceeded apace. The photos says it all. Kioni speaks for herself. And there is no doubt but that Bill Trafford’s eye for what a proper yacht should look like is world-class-plus.

Perhaps the most crucial job of all – getting the counter extension just right. Bill Trafford hit the target perfectly.

Bill Trafford’s eye for a boat is well matched by his skill in working with wood – we can see only one glaring design fault in this photo in the workshop as Kioni take shape in her new form.

The skill in getting the counter extension just precisely right sets the tone of the entire project. And as for the quality of the workmanship in wood – that’s truly a wonder to behold. But what’s this about a design fault in that nearest photo above? Not to worry – it’s not in the boat. It’s to do with the door to the workshop lavatory.

That great boat designer and builder Uffa Fox says in one of his books that whether it’s the privy in the garden, or the lavatory in the boatbuilding shed or wherever, then the door to the lavatory should always open inwards. Thus if you’re taking your proper leisure therein, and seated comfortably and wish to contemplate some good work whether it be in the garden or on the boat under construction in the workshop, then if you’re on your own you can leave the door open the better to appreciate your work. But if someone arrives unexpectedly, you can kick it shut without a bother…….

Although Kioni makes a feature of beautifully finished timberwork, it’s not excessive. The really skilled boat creator knows that less is more, and a discreet yet effective little toe rail is much more pleasing to the eye than some hulking great heavy bit of bulwark or beading.

……came from this

So now you know the style of Bill Trafford’s work, and if you’re interested, his workshop is 70ft X 45ft with a door 15ft wide and 14ft high. He reckons he could do two Kionis a year. But be warned. He always has some other ideas at the back of his mind. His real ambition is to buy a battered old GRP Nicholson 43, lengthen her stern out into something like a Fife counter, give her straight stem the tiniest hint of a clipper bow, stick on an 8ft bowsprit, and turn her into a re-born gaff schooner…………

A standard Nich 43. Bill Trafford’s dream would be to turn her into a 47ft gaff schooner with a classic long Fife counter and a hint of a clipper bow

A standard Nich 43. Bill Trafford’s dream would be to turn her into a 47ft gaff schooner with a classic long Fife counter and a hint of a clipper bow

Wooden Boat Building In Fermanagh: Keeping The History Alive

#HistoricBoats - The storied tradition of wooden boat building in Fermanagh is the subject of a new exhibition at Enniskillen Library from next Monday 29 June to Saturday 4 July.

Photos, anecdotes and artefacts of the era of clinker-built boats and cots before the advent of fibreglass will be on display at the library each day between 10am and 4pm.

And organisers with Lough Erne Heritage are also looking to gather information from local people, many of whom still have valuable old-school boatbuilding knowledge, that could tell us even more about those bygone days.

Stories, photographs, cine film and images of original boats and related artefacts such as hand tools and early outboard engines - if you have them, bring them along for recording in the collection.

Is Being an Olympic Sport Good for Irish Sailing?

#olympicsailing – Water Rat's article: Is ISAF Alive To Sailing's Survival As An Olympic Sport? has raised the issue about the future viability of the Olympic sailing movement and brought reaction from readers, including Midshipman, who says it begs two interesting questions:

· Is being an Olympic sport good for sailing?

· Why have the amazing advances we have witnessed in technology over the last 15 years not made sailing more accessible and less expensive?

With the exception of the Laser (a manufacturer controlled boat which is not cheap at €7,250), none of the boats used in the Olympics are to be found in mainstream sailing.

The explosion in sailing during the 60's and 70's was fuelled by the development of exciting low cost boats built, mainly by amateurs, in plywood using new adhesive and coating techniques.

The turn of the century has seen vast improvements in the technologies used in boat building, making boats lighter, faster, stronger safer, but certainly not cheaper, as amateur construction can no longer compete with the sophisticated techniques of the boating industry.

That is probably why the most popular dinghy class in the world remains the inexpensive and simple Sunfish while low tech Hobie Beach Cats still dominate the multihull scene.

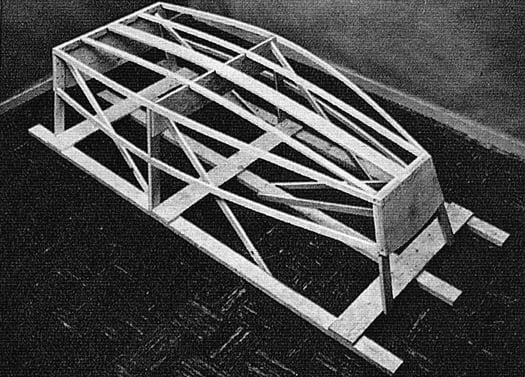

In years gone by, most young sailors got their start in wooden Optimists, often built by enthusiastic parents at modest cost over a couple of weekends and then typically graduated to a home built Mirror or its equivalent for their first experience of multi crewed sailing with multiple sails.

A wooden framework of the early Optimist dinghy

Nothing less than a relatively expensive Glass Fibre Optimist will do now and the Street Cred of young people is dependent on graduating to costly Lasers and 420s. In Ireland this situation is also compounded by the sense of failure youngsters experience if they fail to qualify for one of the Academy or Elite development squads which currently involves over 100 youth sailors of varied abilities.

The scene today – charter boats used at Dun Laoghaire for the 2014 Optimist Europeans

Sailing has become so fixated on exciting performance and elite achievement that it has lost sight of the sheer enjoyment of messing about in boats at modest cost which is the principle attraction to the vast majority of people.

We all admire the highly skilled and motivated sailors who aspire to the ultimate Olympic challenge, but let's face it , what they do has virtually no relevance to the activities of most recreational sailors. ISAF uses racing formats and boats which are not reflective of the sport in general, largely on the grounds of needing to excite TV viewers.

With the exception of horse riding, sailing is probably the most equipment dependent (meaning most expensive) sport in the Olympics. I am not sure that this is a message which ultimately helps encourage people to become involved in sailing.

If we want to use the Olympics as a marketing opportunity for sailing, we should use inexpensive boats which are used on a widespread basis by regular sailors and only have 2 events each for men and women whilst eliminating the cost of shipping boats by supplying evenly matched equipment.

Olympic sailing has created a very costly industry which contributes little back to mainstream sailing. The costs are truly horrendous as demonstrated by the recent announcement that the ISA is appointing an additional CEO to head up a funding programme to raise a further €2.75m a year over and above the €1m plus it receives from the Irish Sports Council for Irish Elite sailing activities.

Does the Irish sailing community believe an annual level of expenditure of €3.75m on elite sailing provides the best economic payback to the sport in Ireland? If we could replicate what has been done in New Zealand, maybe there is a business case which can be justified.

However, €15m seems an outrageous amount of money to propose spending over an Olympic cycle, which is equal to something in excess of €800 on behalf of each member of the ISA.

Let's make sailing accessible, less expensive and more engaging and use the Olympics as a shop window to remove the elitist and esoteric imagery created by the current profile of existing Olympic classes.

What we are doing at the moment is deluding ourselves into believing that presenting our sport like NASCAR or Formula 1 motor racing will attract new people to buy Ford Mondeos and Fiat Pandas. – Midshipman