Displaying items by tag: Historic Boats

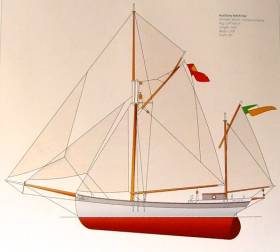

Restored Aigh Vie Launched: Sinking of the Lusitania off the Old Head of Kinsale Brings Special Memories in Connemara Today

It’s a long story of the sea and ships, a story which began with the World War I sinking of the luxury Transatlantic liner Lusitania by torpedoes from a German submarine off the Old Head of Kinsale in 1915 writes W M Nixon.

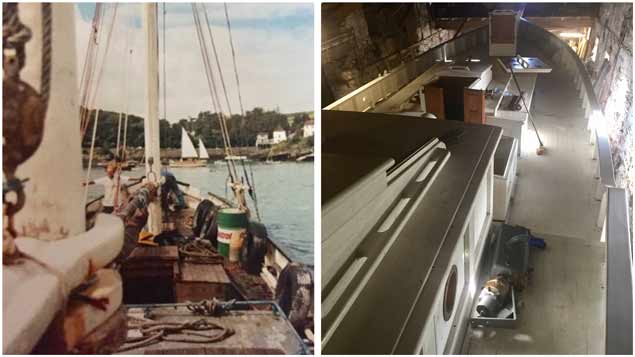

Much has happened since, but the saga moved into a new chapter this past weekend, when Paddy Murphy of Renvyle in the furthest point of northwest Connemara re-launched his 45ft former Isle of Man fishing nobby Aigh Vie into the Atlantic right off his house.

The Aigh Vie has spent two decades in an often storm-battered shed beside the house, being painstakingly re-built as Paddy’s personal dreamship. While he describes himself as a blacksmith, he can turn his hand to anything, and his multiple skills have enabled himself and his partner Siobhan to make good their escape from the claustrophobic life of Dublin, and settle in this magnificently remote frontier post of the Atlantic seaboard.

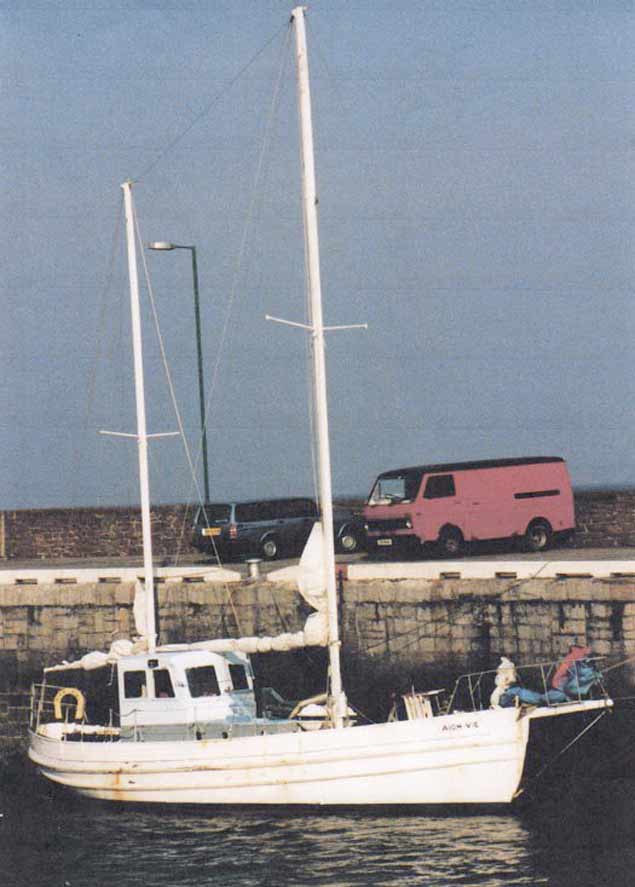

Aigh-vie as she was when Paddy Murphy bought her

Aigh-vie as she was when Paddy Murphy bought her

They brought the Aigh Vie with them overland, for she was then at a very early stage of the re-build. But with the heavy part of the restoration work now completed, it was time and more on Saturday to get her launched into the Atlantic while a southeast wind obligingly provided smooth water for the beach launch, and that noted storehouse of maritime lore Cormac Lowth was there to record the scene and put it all in its historical perspective.

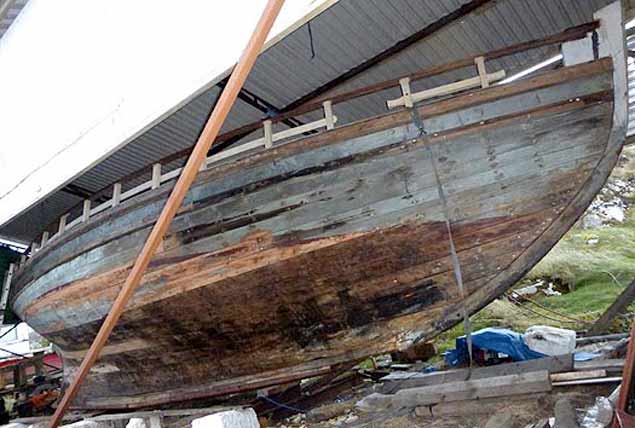

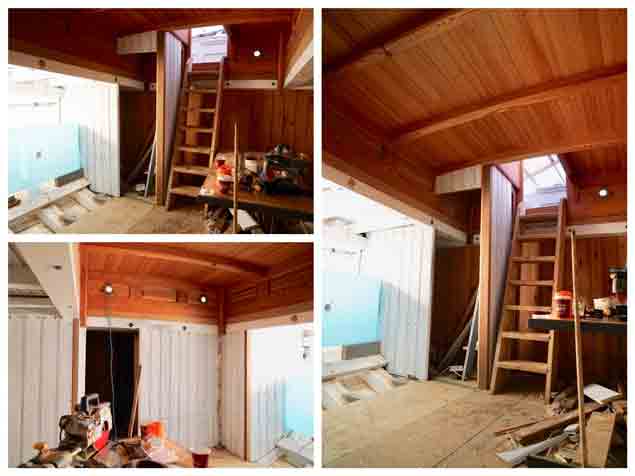

The work at an early stage. Photo: W M Nixon

The work at an early stage. Photo: W M Nixon

Paddy Murphy, a man of many talents. Photo: W M Nixon

Paddy Murphy, a man of many talents. Photo: W M Nixon

With the help of a local fishing boat, Aigh Vie was then moved round to the nearby natural shelter of Ballynakill Harbour and the pier at Derryinver for her first night afloat in many years. But Derryinver pier is a busy place, so Aigh Vie has since been moved up the bay to a fitting-out berth at another quay where there’s less demand on space, and work can proceed uninterrupted on the finishing of many tasks.

So on Saturday night there was a mighty hog roast party to celebrate

No-one has any doubts about the amount of work which still has to be done, and often it will be by Paddy working on his own. But much has been done. The launching has been achieved. So on Saturday night there was a mighty hog roast party to celebrate in the recently-vacated shed, attended both by locals and by people from places more distant whose lives have been intertwined with the story of Aigh Vie.

The restored Aigh Vie sits beautifully on her marks. Photo: Cormac Lowth

The restored Aigh Vie sits beautifully on her marks. Photo: Cormac Lowth

And it is an extraordinary story. When the Lusitania was torpedoed, the nearest vessel was the fishing ketch Wanderer from Peel in the Isle of Man, skippered by William Ball. The Wanderer and her crew saved many lives, and some time afterwards Skipper Ball – who was an employee of the fishing company that owned the Wanderer – received a lawyer’s letter informing him that a sum of money had been anonymously lodged from America to a bank account in Peel for his benefit. The stipulation on the funding was that it was to be used for the building of his own vessel, the fishing boat of his dreams.

The Aigh Vie (it means “Fair Winds” or “Good Luck” in the Manx Gaelic) was the result, and she was launched in December 1916 and registered as a fishing boat in January 1917. But she was so elegant in her hull lines that she was always described as being more like a yacht than a fishing vessel, and after she finished her working career fishing out of Ardglass in County Down, she ended up being owned for recreational use by Billy Smyth of Whiterock Boatyard on Strangford Lough, who cruised her every summer with his family, usually to the west coast of Scotland and sometimes beyond to the Orkneys.

Aigh Vie in a temporary overnight berth at Derryinver Pier on Ballynakill Bay. Photo: Cormac Lowth

Aigh Vie in a temporary overnight berth at Derryinver Pier on Ballynakill Bay. Photo: Cormac Lowth

It is many years since Aigh Vie was bought from Billy Smyth by Paddy Murphy, and he based her for a while in the Dublin area. For now, though, in her re-born state the coast of Connacht provides her home waters. And who knows, but maybe when the fitting-out is finally completed, the far horizons will call. Meanwhile, it’s good to know that the challenge of getting her out of the shed and into the Atlantic has been met.

Yet the mystery still remains as to who it was in America who so appreciated the wonderful rescue work done by the Wanderer in 1915 that they willingly paid for the building of Aigh Vie in 1916. One-hundred-and-two years down the line, it seems their identity remains as elusive as ever

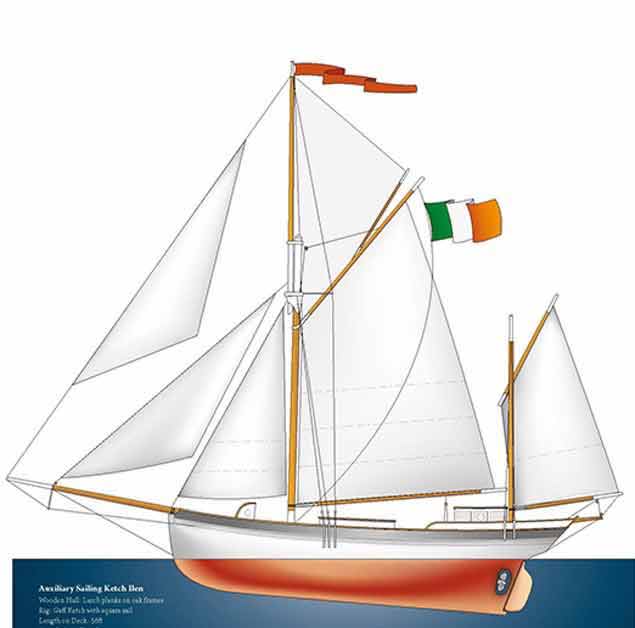

Secret Brotherhood of Can–Do Boating People Help Ilen Project

The restoration of the 56ft ketch trading ketch Ilen (1926) and the re-build of world-girdling 42ft Saoirse (1922) at Oldcourt in West Cork has become a focal point of interest of what might seem to an outsider to be a secret brotherhood of the maritime world writes W M Nixon

It’s not that these people set out to be mysterious or secretive. It’s just that they operate on a different level to the rest of us. Typical of them is Jarlath Cunnane of Mayo. He’s always building boats for himself. He built the special aluminium 15 metre (49ft) exploration yacht Northabout with which he and Paddy Barry and a rugged crew transitted both the Northwest and the Northeast passages.

Northabout returns to Clew Bay and Croagh Patrick after completing the transits of the Northwest and Northeast Passages in 2005. Photo: Rory Casey

Northabout returns to Clew Bay and Croagh Patrick after completing the transits of the Northwest and Northeast Passages in 2005. Photo: Rory Casey

Yet despite Northabout’s alloy build, he’s very much a fan of traditional craft. So when he heard that Gary MacMahon of Limerick and his team were undertaking the ticklish job of stepping Ilen’s new masts in West Cork in a very limited time frame earlier this month, he and frequent shipmate Dr Mick Brogan (he owns the giant Galway Hooker Mac Duach and is much involved in Cruinniu na mBad at Kinvara) simply appeared at just the right time at Oldcourt, and their help was much appreciated.

The 40ft O’Brien Kennedy-designed Swallow, which Wally McGuirk built himself in steel. Photo: W M Nixon

The 40ft O’Brien Kennedy-designed Swallow, which Wally McGuirk built himself in steel. Photo: W M Nixon

Wally McGuirk in his on-board workshop in Swallow. Photo: W M Nixon

Wally McGuirk in his on-board workshop in Swallow. Photo: W M Nixon

On the opposite side of the country from Mayo, Wally McGuirk of Howth is another enthusiast for traditional boat-building who nevertheless was not slow in using basic steel construction for his 40ft dream yacht Swallow, the last design by O’Brien Kennedy. Wally built her himself, and since then has introduced all sorts of inventive additions, a notable one being the legs which support the boat if she is going to dry out at low water.

Wally reckoned the traditional legs bolted on to the outside of the hull amidships are an unsightly nuisance. So he built a couple of hefty steel casings at a sight angle inside Swallow, and these neatly house the legs which are retracted virtually out of sight when not in use.

Wally McGuirk with one of his special legs on board Swallow. Photo: W M Nixon

Wally McGuirk with one of his special legs on board Swallow. Photo: W M Nixon

The internal housings for Swallow’s legs intrude very little on the accommodation. Photo: W M Nixon

The internal housings for Swallow’s legs intrude very little on the accommodation. Photo: W M Nixon

Yet although he enjoys the freedom of innovation which steel construction permits, Wally’s heart is in wood. And as he happens to be a property developer of sorts, quantities of choice vintage timber have come his way over the years. Thus when he was making major alterations to a 1798 building which had once been a brewery in Brunswick Street in old Dublin, he ended up with some lovely perfectly-seasoned pine of hefty proportions which he stored carefully, such that the rain has never fallen on it.

He could never think of a suitably idealistic use for it until the Ilen Project developed, and that hit the target. So last weekend the beautiful timber of 1798 journeyed to West Cork, and in time it will make a characterful cabin sole in the handsome ship.

Ilen’s interior has been finished in Douglas fir of 1831 vintage. Photos: Gary MacMahon

Ilen’s interior has been finished in Douglas fir of 1831 vintage. Photos: Gary MacMahon

Meanwhile, Gary MacMahon had sourced some quality Douglas fir of 1831 from a building in Limerick, and that has already been deployed to good effect in Ilen’s cabins, where seven proper seagoing bunks will be provided.

As for the Ilen Project generally, the recent flurry of news about the re-development of the land around the Ted Russell Dock beside the city centre has reminded everyone that Limerick is now Ilen’s home port, and very well it looked too on a mock-up applied to Ilen’s handsome transom this week.

The second in a series of maritime themed conferences jointly organised by National Museums Northern Ireland, National Historic Ships UK, Robin Maesfield, (Author) and Gerry Brennan, (Silvery Light Sailing), highlights Ulster's Maritime Heritage.

The seminar is being organised by a group of maritime enthusiasts keen to promote and inform on the Maritime Heritage of Ireland.

The Conference Venue is the Kennedy Room, Cultra Manor, Ulster Folk & Transport Museum from Friday 27th April 2018 - 0930 (Registration) – 1530

The schedule for the day is:

Welcome from Kathryn Thompson, Director NMNI,

Tom Cunliffe, Maritime Journalist and TV Celebrity (video)

An introduction to UFT Museum Maritime Collection - William Blair,

Kellys Belfast Colliers - Kelly Wilson

The Merchant Schooner ‘Result’ - Christopher Kenny,

Irish Schooners in WWII – Joe Ryan

Fermanagh Cots and Maritime Heritage – Fred Ternan

Portaferry Schooners – James Elliott - PAST

National Historic Ships UK and Shipshape Register

Conducted Visit to’ The Result’ Schooner & Artefact Exhibition

Larry Duggan 1927-2018 RIP

Larry Duggan, who has died this week at the age of 90, was one of the best-known and most popular figures in Wexford, and internationally renowned in the maritime world as a versatile builder of wooden boats of many kinds, all to the highest standards. But important as boats and the sea were to this energetic man, there was much more to him than that – he was even more than someone of many active interests, he was in reality a universe of activities, all pursued with enormous enthusiasm and dedication.

Born in Rosslare in 1927, with marriage to Margaret (Madge) the newly-married young couple settled in Wexford town, and their home for their final forty years together was at Carcur in their house called The Moorings on the south shore of the Slaney Estuary, in that pleasant area above the bridge near the Boat Club, where they raised their family of Laurence Jnr, the twins Tom and Will, and their daughter Ann.

Larry’s prime day job was as a builder and developer, but he also owned a saw-mill, for timber and working with it was one of his many passions. From an early age, his interest in boats was allied to this love of wood, resulting in a developing skill in boat-building projects which he undertook in whichever suitable workshops happened to be available to him in Wexford.

However busy he might be, Larry Duggan (right) always had time to discuss the attractions of traditional boat-building

However busy he might be, Larry Duggan (right) always had time to discuss the attractions of traditional boat-building

It’s said of Larry Duggan that he was never still, and was always happiest when thinking of several things at once. Thus if he was on a house-building or carpentering job, he’d always be keeping a eye out for a piece of timber which might be better deployed in his evening’s boat-building activities.

As to how he managed all this, his son Will fondly recalled today that for his father, the 18-hour day was the norm, but he never regarded his long sessions of boat-building as work. In some ways, they were the very essence and expression of his life.

Yet somehow he found time for many other interests including ornithology, to which he invariably gave enthusiastic voluntary input. For instance, when the World Plough Championship was coming to Wexford, he was on the Organising Committee, and played a key role in the crucial task of laying out the top ploughing areas for the finalists.

On the maritime side, naturally he was a productive supporter of the RNLI and the Maritime Society, with his contribution being recognized by his award of the Maritime Medal. And his knowledge was such that when a Viking ship was to be built for the Wexford Heritage Park, when a team came from Scandinavia to oversee its construction, very quickly they found that a significant input from Larry Duggan was essential to the project’s successful conclusion.

The finished product from Larry Duggan was always a joy to behold.

The finished product from Larry Duggan was always a joy to behold.

But his greatest joy in boat-building was in creating craft which had historic and contemporary Wexford links. He built many Wexford cots which, uniquely among the Irish river cot type, had developed a seagoing version – the Rosslare cot – in order to deal effectively with the many challenges for small working craft posed by the Slaney’s open and sandy estuary, and the sea immediately off it.

Then when local recreational sailing developed at the old area known as Maudin Town southeast of Wexford town itself, thanks to the fact that Larry had built three Dublin Bay Mermaids for the local fleet, he was able to secure second-hand Mermaid sails which could be re-cut for use in these neighbourhood boats, which have gone on to become distinctly turbo-powered versions of the traditional Wexford cot.

The Wexford cots for receational sailing at an early stage of development, when Larry Duggan played a key role in building boats, sourcing second-hand sails, and teaching the basics of racing

The Wexford cots for receational sailing at an early stage of development, when Larry Duggan played a key role in building boats, sourcing second-hand sails, and teaching the basics of racing

The contemporary Wexford sailing cot has continued to develop for racing purposes

The contemporary Wexford sailing cot has continued to develop for racing purposes

Not only did he help their crews to source sails, but he taught them to sail and race as well, for he was as able afloat with sails and boats as he was in the workshop building them. His skill was such that when the local estuary fish firm of Lett’s required a fleet of 24ft shoal-draft motor-boats to service their estuary fishing and shellfish beds, it was to Larry that they turned. It was quite a project for an “amateur” builder, but he succeeded so well that those boats continue to be a familiar and active sight in Wexford Harbour.

He cherished Wexford’s Irish traditions and Viking heritage alike, and when a special classic Viking skiff was required to be part of the Royal Silver Jubilee Celebration Fleet on the Thames in London, it was reckoned that Larry’s unique talents were ideal to create something with the essential authenticity, and he took extra pleasure in fulfilling this demanding “export” order.

His eightieth birthday celebrations in Wexford in 2007 provided one of the town’s most memorable parties, but retirement of any kind was far from Larry Duggan’s mind. He continued building boats until well into his eighties, and even as his 90th birthday approached, he was more than willing to open up his workshop to take on any small job involving work on wood for his many friends.

Sadly, his beloved Madge was to die age 89 in 2014, but for his 90th birthday on 12th August last summer, among a huge number of greetings was a personal message of goodwill from President Michael D Higgins. Now, the great and good Larry Duggan is gone from among us. But he leaves cherished memories with hundreds of people worldwide. Our thoughts are with his family and many close friends in their sad loss.

WMN

Sprit Sails & Clinker Boats on Lough Erne

In the 1800s and into the 1930s, double ended Clinker built boats, yawls, were seen and used on Lower Lough Erne. These historic boats were about 17 or 18 feet in length and about 5 feet wide and were propelled by oars or a Sprit sail writes Fred Ternan of Lough Erne Heritage.

They were very similar to the Drontheim used around the North coast and as far south as Donegal Bay. Drontheims would have been seen by the people from Lough Erne when trading with Ballyshannon and this may have brought about the introduction of a similar boat to Lower Lough Erne, albeit on a smaller scale than the 27–footers used on the sea. There are records in the local papers of Donegal men coming to Lough Erne for rowing races in 1824. The shape of the stem used by some of the builders on Lough Erne and the sail plan was very similar and many of the Lough boats were built using a hog.

Gradually the shape of the yawl changed to a boat with a transom which was a better load carrier and was also a little simpler to build. The Sprit sail continued to be used and clinker boats continued to be built on and around Lough Erne into the 1960s and 1970s when wood was replaced by GRP. The Sprit sail was occasionally used into the 1960s by which time outboard engines had become more reliable. Another reason for its use on the long journeys on Lower Lough Erne was economy.

The moulds he used were retained and recently the first clinker boat built to those moulds since the 1960s, approximately 50 years ago has been built by George and Fred Ternan, cousins of Douglas Tiernan and members of Lough Erne Heritage. Using memories of the build and use of those wooden boats and the moulds, this boat when completed and launched will hopefully be as capable in the waves of the large expanse of Lower Lough Erne as the boats built by Douglas.

An original Sprit Sail

An original Sprit Sail

It will be fitted out with a Sprit sail, originally made from calico and two pairs of oars and these methods of propulsion will be demonstrated on the day of the launch and afterwards. At least five or six clinker boats on Lower Lough Erne were still using the Sprit sail as a method of propulsion in the 1960s. The boats did not require the installation of a rudder as one of the oars was used to steer, being placed in a rowlock positioned in the stern crutch or quarter knee, all in all a very simple method of boat propulsion and steerage.

Ireland’s Contribution to the International Classic Wooden Boat Movement

The traditional and classic wooden boat-building movement is gaining momentum in many parts of the world. It can be part of educational and training schemes which provide skills and purpose in life, usually for young people but also for older folk seeking a new and very absorbing interest. Or it could be to preserve an indigenous boat type whose very survival is at risk. Then again, it may be for the simple pleasure of creating something which produces a tangible result from a satisfying personal project, or a worthwhile community effort. Whatever the reason, Irish sailing’s long history enables it to make a unique contribution to today’s proliferation of classic and traditional newly-built or restored craft emerging from workshops large and small in many parts of the world. W M Nixon looks at some aspects of a fascinating trend.

The half century or so between 1890 and 1945 will be seen by most historians as a period of exceptional global hostility, certainly as measured by the number of wars which were fought during it. So it’s remarkable that an activity like recreational sailing, which needs peaceful conditions to thrive, should have developed so much during that turbulent time.

Admittedly much of the development took place in the “Golden Era” between 1890 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914. But progress was being made in sailing for much of the rest of the period despite the often unfavourable conditions. And for Ireland, that historic time of progress is being reflected today in the number of historic designs for Irish classes which are now first choice for boat-building schools, and other special projects, in many countries including Ireland itself.

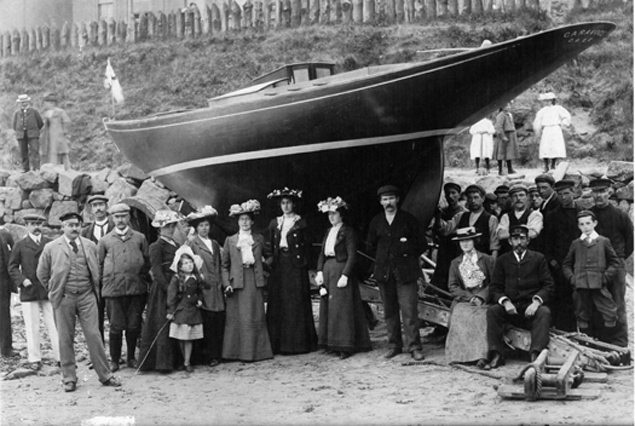

The Alfred Mylne-designed Dublin Bay 21 Garavogue, new-built and ready for launching by James Kelly of Portrush in 1903. Photo courtesy Robin Ruddock

The Alfred Mylne-designed Dublin Bay 21 Garavogue, new-built and ready for launching by James Kelly of Portrush in 1903. Photo courtesy Robin Ruddock

During that half century between 1895 and 1945 when many new local one design classes appeared, Ireland had a pioneering role, as the One Design concept had been first promoted by Thomas “Ben” Middleton’s Water Wags in Dublin Bay in 1887. Thus it was always an innovation which had special resonance in the Irish context, an ideal which it seemed only natural to follow.

Then too, the Royal Alfred YC of Dublin Bay had been promoting the virtues of amateur sailing since 1870 and earlier, so the level playing field provided by One-Designs was a natural follow-on for continuing such enthusiasm. But sustained and long-time support for a particular One-Design type – once it had proved itself satisfactory for the waters on which it sailed – also had much to do with the geography and social structure of Irish sailing.

Put simply, most sailors of the new and growing one design classes in Ireland lived in close proximity to where their boat were based and raced. In contrast elsewhere, thanks to the comprehensive 19th Century railway systems very effectively serving large conurbations such as London and Paris - and to a lesser extent Glasgow and New York - when the weekend was over, many owners and crews headed back to town, sometimes over quite long distances from their boat’s home port.

Garavogue in the final stages of a race when the finishes were still within Dun Laoghaire Harbour. Her owner and crew would have lived within easy reach of the harbour, and the comfortable social bonds within the DB21 class contributed to its long life from 1902 to 1986.

Garavogue in the final stages of a race when the finishes were still within Dun Laoghaire Harbour. Her owner and crew would have lived within easy reach of the harbour, and the comfortable social bonds within the DB21 class contributed to its long life from 1902 to 1986.

But in Ireland, whether it was Cork, Dublin or Belfast, the boat was always nearby, you might meet your fellow sailors quite often during the working week, and evening racing was an important part of the programme. In the greater Dublin area in particular, the cohesive nature of society meant that once a class was popularly established, it thrived so much that some boats from the late 1890s and early 1900s are still in existence and actively racing today.

This means that when a boat-building school seeks a meaningful design which will give added depth to their activities, they know they only have to turn to the wide selection of historic Irish classes to find a boat of suitable size which will have an element of international recognition, it will give those building her an encouraging sense of connection to the past for instructors and trainees alike, and at a practical level, they know there’ll be a diligent class measurer to keep them on track as the job progresses.

A further alternative technical element is added when the no-longer-seaworthy old hull of a revered classic is acquired, and it is then patiently analysed in a process which is a mixture of dissection, re-build and re-creation. Either way, whether building from scratch, or re-creating through various levels of re-building, the learning process is given many useful extra facets.

Water Wags in Dun Laoghaire Harbour. Founded as a class of 13-footers in 1887 and re-born in this larger 14ft 3in version by designer Maimie Doyle in 1900, they have become one of the most popular Irish classic designs for boat-building schools. Photo: W M Nixon

Water Wags in Dun Laoghaire Harbour. Founded as a class of 13-footers in 1887 and re-born in this larger 14ft 3in version by designer Maimie Doyle in 1900, they have become one of the most popular Irish classic designs for boat-building schools. Photo: W M Nixon

And as Irish sailors were not shy in asking designers of international repute to create their new One Designs for them, these re-build or new-build projects may have the added lustre of classic stardom with their undoubted historical significance. Thus in recent years while we may have had new boats being built to the old designs of Irish designers such as Maimie Doyle, Hebert Boyd, John B Kearney and O’Brien Kennedy, equally builders from abroad have been in touch with class associations and other sources in Ireland in order to re-create boats to the designs of William Fife and Alfred Mylne of Scotland, and Morgan Giles of England.

Thus at the moment we have Water Wags being built in Spain and America, Dublin Bay 24s are at various stages of being re-created in Spain, America and France, in France they have also built a Howth 17, another Water Wag and a Shannon One Design, it’s said there’s a Howth 17 being built in the boat-building training school attached to the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, and not surprisingly we hear of enquiries made of Irish class association from those havens of DIY boat-building enterprise, Australia and New Zealand.

Two of the new Howth 17s in their first season in 1898, before sail numbers had been allocated.

Two of the new Howth 17s in their first season in 1898, before sail numbers had been allocated.

The Howth 17 Orla under construction at the Skol ar Mor boat-building school in France, May 2017

The Howth 17 Orla under construction at the Skol ar Mor boat-building school in France, May 2017

In fact, if we look at the range of living or still very well remembered classes in Ireland which have the potential to make designs available for such classics projects, the choice is remarkably comprehensive in size and type. They range through the 14ft IDRA 14s (O’Brien Kennedy, 1946), the 13ft and now 14ft 3ins Water Wags (R A MacAllister 1887 & Maimie Doyle 1900), the Castletownshend Ettes of the 1930s come in at 16ft, at 17ft you have both the Shannon One Designs (Morgan Giles 1922) and the Mermaids (John Kearney 1932), at 18ft we’re already into keelboats and the Belfast Lough Waverleys (John Wylie 1902), move up to 22ft and you have the Linton Hope-designed Fairy Class (1902) on both Belfast Lough and Lough Erne, and there were also the Fife-designed Belfast Lough Class IIIs of 1896, and then at 22ft 6ins there are the Howth 17s by Herbert Boyd (1898).

Up at 25ft there are the Glens (Alfred Mylne, 1945) in Dun Laoghaire Harbour and on Strangford Lough, and also on Strangford Lough at 28ft 6ins there are the Rivers (Alfred Mylne, 1920). Moving towards the 30-31ft mark, we have the Cork Harbour One Designs (William Fife 1896) and the Dublin Bay 21s (Alfred Mylne 1902), and finally above that, with all of them around the 37ft 6ins LOA size, are the Belfast Lough Class I (Fife 1897), the Dublin Bay 25s (Fife 1898) and the Dublin Bay 24s (Mylne, 1938).

Strangford Lough River Class – designed by Alfred Mylne in 1920, they are believed to be the world’s first Bermudan-rigged One Design. Photo: W M Nixon

Strangford Lough River Class – designed by Alfred Mylne in 1920, they are believed to be the world’s first Bermudan-rigged One Design. Photo: W M Nixon

The Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle, an Alfred Mylne design of 1938, was restored in France

The Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle, an Alfred Mylne design of 1938, was restored in France

The attraction of such a good selection is that anyone minded to re-create a classic with a distinguished design and sailing provenance can choose a boat of manageable size from the range available in Ireland. A genuine classic doesn’t have to be a biggie. Keeping it manageable – and in many cases keeping it comfortably trailerable – is the secret of a harmonious project, and the eclectic list of classic projects available for sourcing in Ireland not only offers boats of every size and type up to 40ft, but you can come to Ireland and absorb the atmosphere of the places where the idea of the boat was first conceived, and meet current enthusiasts for sailing the boat which gives a vibrant connection both to the present and the past.

Don’t assume, though, that though it may be happening abroad, there’s nothing going on in Ireland. On the contrary, the possibilities of the Irish classics have been exploited every which way. Serial classics enthusiast Hal Sisk of Dun Laoghaire has instigated so many projects that it’s difficult keeping track, but his CV includes the Peggy Bawn, new Water Wags built in classic style, glassfibre Colleens from an 1897 design, and currently the building of a Dublin Bay 21 from the original ballast keel upwards by Steve Morris of Kilrush, utilising multi-skin construction based on laminated frames.

New life for the 1902-designed DB 21 Naneen in Steve Morris’s workshop in Kilrush. Photo: Steve Morris

New life for the 1902-designed DB 21 Naneen in Steve Morris’s workshop in Kilrush. Photo: Steve Morris

The construction method may be new, but that’s undoubtedly the classic hull of a DB 21 emerging in Kilrush. Photo: Steve Morris

The construction method may be new, but that’s undoubtedly the classic hull of a DB 21 emerging in Kilrush. Photo: Steve Morris

As for Jimmy Furey on the Roscommon shores of Lough Ree, his examples of completely traditional classic style construction of Shannon One Designs and Water Wags – working most recently with Cathy MacAleavey – results in what can only be described as Chippendale work, while down in Ballydehob in West Cork there’s a whole nest of classic restorers, with Rui Ferreira setting quite a pace with new Ettes, a restored Kim Holman Stella, and a much-revived Howth 17.

The Castlehaven Ette Class – Rui Ferreira has been building to this design

The Castlehaven Ette Class – Rui Ferreira has been building to this design

Over on the east coast, when times are hectic in classic boatbuilding, people have found that John Jones over in Anglesey does a very good line in stylish clinker construction, but the venerable Howth 17s – not all of which are operated on large budgets – are currently being kept going by Larry Archer of Malahide, who has a workshop up-country where three of these golden oldies are currently receiving the TLC.

Asgard’s dinghy was re-created in classic style by Larry Archer. Photo: W M Nixon

Asgard’s dinghy was re-created in classic style by Larry Archer. Photo: W M Nixon

Larry is something of a renaissance man in the boat maintenance, repair and building arena, as he is right up to speed with everything to do with glassfibre, yet when Pat Murphy and his group got together to re-create Asgard’s dinghy, it was Larry Archer who delivered the goods, beautifully built in classic clinker style.

As to his present work with the Howth 17s, that is part of a broader project being driven by Ian Malcolm and fellow Seventeen sailors, who may be looking at a class of 23 boats in the foreseeable future. Apart from the new boat built last year in France and the boat reputedly under construction in Annapolis, in a secret workshop on the Hill of Howth, yet another new Howth 17 is quietly under construction to a very high standard.

Such things take time, as the group in Clontarf Y & BC demonstrated when they set out to build a classic timber IDRA 14 for the class’s 70th Anniversary in 2016. They allowed themselves plenty of time, but it was tight enough in the end, yet by the successful conclusion a special bond had been formed among the build team in their Men’s Shed enterprise. It said everything about the deeper benefits of getting involved in a manageable project using time-honoured methods and traditional materials to create something of lasting beauty, value and utility.

The new IDRA 14 ready for launching at the class’s 70th Anniversary Regatta at Clontarf. Photo: W M Nixon

The new IDRA 14 ready for launching at the class’s 70th Anniversary Regatta at Clontarf. Photo: W M Nixon

Ireland’s Pioneering World-Girdler Saoirse Will Sail Again

Work began this week at Oldcourt near Baltimore in West Cork on reconstructing Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse. One of the most remarkable sailing vessels in Irish and world maritime history, the 42ft Saoirse is unique in many ways. W M Nixon gives some of the background to a complex story.

The early 1920s in Ireland are generally remembered as a time of extreme turmoil, with a War of Independence, the establishment of the Irish Free State with Northern Ireland partitioned, and a Civil War which was followed by a restless period as the fledgling State developed its new identity.

Yet in this uneasy time of frequent disruption, in Baltimore in West Cork a special boat, a proper little ship, was built in 1922 to become an ocean voyager which provided a vision of a more peaceful time for a world still only slowly recovering from the horrors of World War I in 1914-1918.

This unique sailing ship was also a maritime inspiration for the new Ireland, uncertain of itself in an uncertain world. For this was Conor O’Brien’s characterful 42ft ketch Saoirse, which he designed himself, and with which - between 1923 and 1925 – he pioneered the round the world route south of the Great Capes, an ocean voyaging “first” which was forever written into world sailing history.

The scale of Conor O’Brien’s achievement at the time is difficult for us to grasp today, when we are aware that the Great Southern Ocean, which runs unhindered round the globe and regularly generates extreme storms, can indeed be navigated by relatively small craft, albeit with the strongest of construction, the best of equipment, and experienced crews.

But in the early 1920s, it had a completely fearsome reputation, and rounding Cape Horn was a venture undertaken only by the most capable and usually very large sailing ships, or the most powerful steamers. So when the little Saoirse rounded the Horn from New Zealand in the last of the daylight on Tuesday December 2nd 1924, it was a pioneering achievement for everything which has come since, including the Golden Globe, the Whitbread Race, and the Volvo Ocean Race.

Saoirse departs from Dun Laoghaire, June 20th 1923. Photo: Irish Times

Saoirse departs from Dun Laoghaire, June 20th 1923. Photo: Irish Times

In Ireland, the greatness of what Conor O’Brien and Saoirse had done was recognized at the time, and his departure from Dun Laoghaire on June 20th 1923 was well celebrated and reported in the Dublin newspapers. Accounts of some aspects of the voyage then appeared in the press in Ireland during its progress, and Saoirse was welcomed back to Dun Laoghaire afloat by Dublin Bay Sailing Club cancelling its racing for the day to provide an escorting fleet, and ashore by a crowd of at least ten thousand, followed by a ceremonial parade into the city with the day concluding with a gala dinner.

After that, O’Brien was busy with writing the story of the voyage for what was to be a popular book, Across Three Oceans, and seeing through the fulfillment of a contract for the construction of a larger version of Saoirse to be the inter-islands communications vessel for the Falkland Islands, for the islanders there had been much impressed by the little ship’s sea-keeping power when she came into port with Cape Horn successfully astern.

Good weather at sea, and time to set Saoirse’s stu’nsails. The ability to use squaresails was fundamental to OBrien’s design concept.

Good weather at sea, and time to set Saoirse’s stu’nsails. The ability to use squaresails was fundamental to OBrien’s design concept.

The 56ft ketch Ilen was the result of this, and O’Brien – crewed by Cape Clear men Con and Denis Cadogan – sailed her out to the Falklands in 1926 from his home port of Foynes in the Shannon Estuary. For although his boats were built in Baltimore by Tom Moynihan and his team at the boatyard attached to the Fisheries School, the O’Brien ancestral lands were along the south shore of the Shannon Estuary, while his first steps afloat were at Foynes, though he also learned sailing at Derrynane in West Kerry where the family took summer holidays. But from 1914 onwards, as the effects of Land League and other factors diminished the family estate, Foynes Island was both his home and his home port in Ireland.

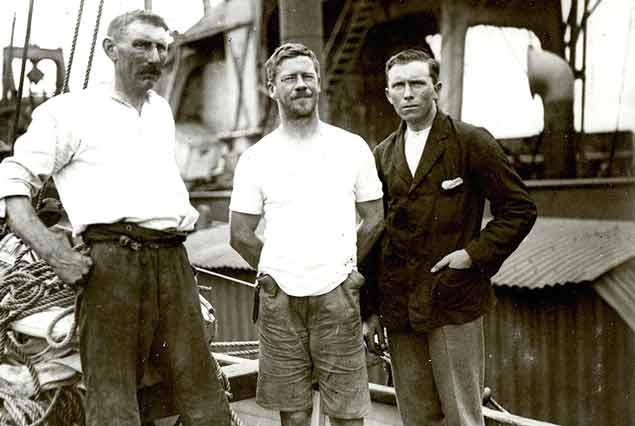

Conor O’Brien (centre) with Con and Denis Cadogan of Cape Clear, who sailed the Ilen with him out to the Falklands.

Conor O’Brien (centre) with Con and Denis Cadogan of Cape Clear, who sailed the Ilen with him out to the Falklands.

However, with the publication of Across Three Oceans and the completion of the Ilen contract, his diminishing income was temporarily boosted, and 1927 was celebrated with the ketch-rigged Saoirse being given a rather spectacular new rig which, despite the same masts being retained, made her look like something of a small brigantine, and with this O’Brien set out to do the Fastnet Race.

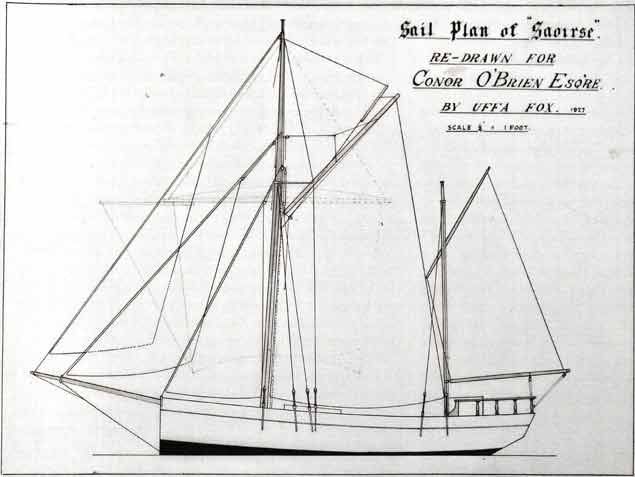

This meant he spent some time in Cowes beforehand, where he was much feted, with the legendary designer Uffa Fox taking off Saoirse’s lines. For although she was rightly described as “a bluff-bowed little boat”, by the standards of the day she had achieved some formidable 24-hour runs during her circumnavigation, and Uffa Fox was determined to see if he could find some special secret to her shape to explain the high average speeds.

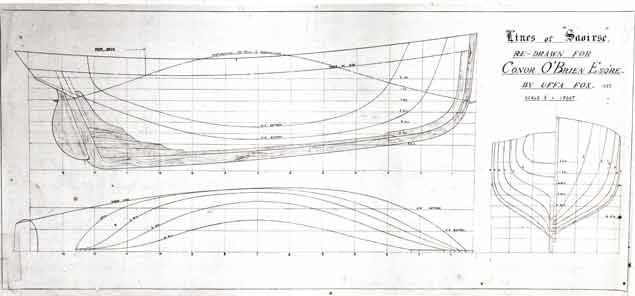

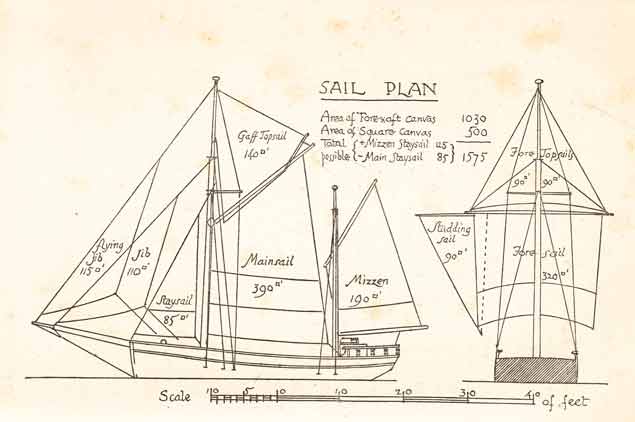

Why did she sail so well? Saoirse’s world-girdling sailplan as taken off by Uffa Fox in Cowes, 1927. The lightly-sketched squaresails were the secret of her steady downwind speed

Why did she sail so well? Saoirse’s world-girdling sailplan as taken off by Uffa Fox in Cowes, 1927. The lightly-sketched squaresails were the secret of her steady downwind speed

Saoirse’s hull lines as taken off by Uffa Fox.

Saoirse’s hull lines as taken off by Uffa Fox.

Saoirse during the 1927 Fastnet Race. Buoyed up with fresh income, Conor O’Brien gave her rig a new look, but it still uses the same masts.

Saoirse during the 1927 Fastnet Race. Buoyed up with fresh income, Conor O’Brien gave her rig a new look, but it still uses the same masts.

But the secret was Conor O’Brien himself. Although the Fastnet Race was dismal for Saoirse as it involved much windward work, off the wind with his nerves of steel he was able to drive his peculiar little ship well beyond her theoretical limit. Yet he almost always brought her to port in one piece, and his judgment of what was possible was renowned.

From this you might expect a stern steady silent type, but Conor O’Brien (1880-1952) was a man of many talents and a mass of contradictions. Short-tempered, sometimes voluble to excess, he expected too much of crews who were sometimes casually recruited, and in all he may have had as many as 17 different people crewing with him during Saoirse’s circumnavigation.

Away from his sailing, his life sometimes seemed aimless. Reared largely in England though holidaying in family properties in Ireland in the summer, following some changes of direction he finally qualified as an architect, and after 1903 he lived for some years in Dublin. Mountaineering was his main outdoor activity, but soon he was further into sailing, and by 1910 he’d bought the hefty cutter Kelpie which he modified for cruising with conversion to a ketch.

Another interest was support of Home Rule for Ireland, and in July 1914, Kelpie joined Erskine Childers’ Asgard in going to collect the arms for the Irish Volunteers from a rendezvous at the Ruytigen Lightship off the Belgian coast. While Asgard’s consignment of Mauser rifles was spectacularly landed in broad daylight in Howth on July 26th, the Kelpie’s cargo was brought ashore at night a few days later at Kilcoole in County Wicklow, having been trans-shipped to the auxiliary yacht Chotah, owned by another distinguished sailing man with direct Limerick connections, the surgeon Sir Thomas Myles.

Within a very few days, the entire scene changed with the outbreak of the Great War, and most of the leading gun-runners were to serve with the British forces. Despite his Home Rule enthusiasm, O’Brien had since 1910 been a member of the Royal Naval Reserve, which had given him useful training for his growing involvement in sailing. Between 1914 and 1918, it provided him with sometimes uneven war experience, for his temperament was much more suited to small unit action than anything involving significant numbers in some sort of organised form.

Post war, he returned to an Ireland which since the 1916 Easter Rising was moving inexorably towards independence and inevitably towards partition. When a unofficial Independent Provisional Government was set up in 1919 in a sort of parallel universe functioning effectively in opposition to British rule from Dublin castle, he offered his services to it with the Kelpie, and was a seaborn Fisheries Inspector for this alternative administation on the West Coast in the summer of 1920.

The situation was confused, to say the least, and in 1921 he went off cruising to Scotland single-handed, with some mountaineering planned in Skye. Returning alone through the North Channel and slowly beating to windward at night, he slept through the ringing of an alarm clock, and the heavy Kelpie came ashore in the foggy dark, well stuck on rocks near Portpatrick on the Scottish coast, and slowly but inevitably became a total loss.

O’Brien appeared out of the morning mist into Portpatrick Harbour, rowing in his little dinghy with all that remained of his worldly possessions about him, for he had sold his house in Dublin, and all he had for home was the use of a family cottage on Foynes Island.

As he recovered both there and with family in Dublin from his ordeal – typically blaming the alarm clock – he started finalizing the designs of an ocean-going voyager. For although he had no personal experience of long sea voyages under sail in a small yacht, he had long wished to do so, but had known the Kelpie was far from ideal for such ventures. What he wanted was a boat of simple ketch rig capable of setting proper square sails for long runs in the Trade Winds.

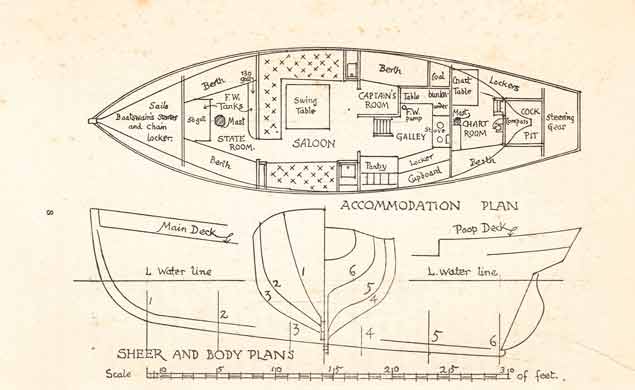

Saoirse’s plans as drawn by Conor O’Brien for his book Across Three Oceans – the short counter stern was an addition insisted on by the boatbulders of Baltimore.

Saoirse’s plans as drawn by Conor O’Brien for his book Across Three Oceans – the short counter stern was an addition insisted on by the boatbulders of Baltimore.

His acquaintance with the skills of Tom Moynihan and his shipwrights in Baltimore had come about when Kelpie had been damaged during severe weather off the Mayo coast during his season in 1920 as a Fisheries Inspector. The repairs at Baltimore satisfied even the pernickety O’Brien, so as the winter of 1921-22 progressed, negotiations led to the beginning of the construction of a 40ft ketch of a virtually unique design.

She had been kept down to 40ft overall to fit into O’Brien’s very limited budget, but Tom Moynihan felt that would make her so dumpy as to be ugly, a poor advertisement for the boatbuilders of Baltimore. So he and his men quietly increased her overall length to 42ft by the addition of a very fore-shortened counter which redeemed the situation, and O’Brien was later to admit that, in this at least, Tom Moynihan had saved him from himself – his original version of Saoirse would have been something of an ugly duckling.

Nevertheless the new ketch was a boat of very primitive type. When we consider that just three years later, William Fife was to design the extremely elegant 70ft Bermudan-rigged Hallowe’en which went on to take line honours in the 1926 Fastnet Race, by superficial comparison Saoirse seems like a mighty backward leap of at least a hundred years in design development.

The 70ft Fife-designed cutter Hallowe’en, line honous winner in the 1926 Fastnet Race, at the Royal Irish YC in Dun Laoghaire. Her design appeared just three years after Conor O’Brien designed Saoirse. Photo: W M Nixon

The 70ft Fife-designed cutter Hallowe’en, line honous winner in the 1926 Fastnet Race, at the Royal Irish YC in Dun Laoghaire. Her design appeared just three years after Conor O’Brien designed Saoirse. Photo: W M Nixon

Yet which boat would you rather be on board for long periods at sea? Like virtually all yachts of her era, Hallowe’en’s galley was well forward in a position of maximum movement in any seaway, and while her wide saloon was stylishly comfortable in port, at sea it was too spacious. On deck, the only comfort is for two or three in the small cockpit.

By contrast, with the accommodation layout of Saoirse, Conor O’Brien deployed his full architectural enthusiasm for the Arts & Crafts concepts of simplicity, comfort and functionality. He placed the homely galley well aft, he created a saloon which would have felt appropriate in a cosy cottage yet worked extremely well in port or at sea, and in all he created a comfortable little ship of suprisingly good performance which sailed in harmony and provided accommodation that fitted around you like a much-loved jacket.

Saoirse’s accommodation layout as drawn by Conor O’Brien was positively homely. In placing the galley well aft, he was way ahead of his time

Saoirse’s accommodation layout as drawn by Conor O’Brien was positively homely. In placing the galley well aft, he was way ahead of his time

This reassuring homeliness of Saoirse was well proven in the years following her great voyage. In 1928 Conor O’Brien – then aged 48 – was tamed a little, and certainly slightly domesticated, when he married Kitty Clausen, an English artist from a noted creative family of Danish descent. Her family had links to Cornwall, to which O’Brien was already attracted as he found the increasingly conservative and repressive mood of the new Irish Free State to be very much at variance with the liberal Home Rule ideals he’d supported in 1914 and again in 1920 when he’d sailed as a fisheries inspector.

Thus the southwest coast of Cornwall became their home area, with Saoirse based at St Mawes on the east side of Falmouth Harbour. But soon they were on their way, cruising to the Mediterranean, where they overwintered with a base at Ibiza – very different from what it is today – while Conor wrote, and Kitty sketched and painted.

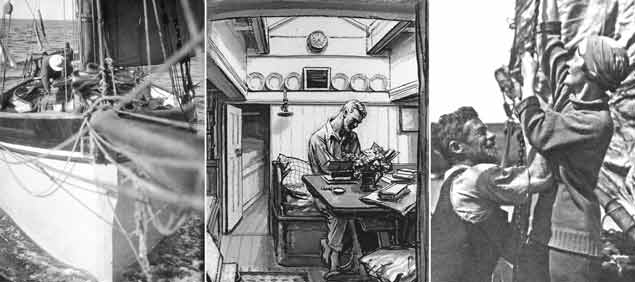

Married life aboard Saoirse for Conor OBrien and Kitty Clausen. On left, the little ship makes her easy way across the Mediterranean, at centre Conor enjoys the comfort of the homely saloon, and at right the newly-weds hoist sail. Photos courtesy Gary MacMahon

Married life aboard Saoirse for Conor OBrien and Kitty Clausen. On left, the little ship makes her easy way across the Mediterranean, at centre Conor enjoys the comfort of the homely saloon, and at right the newly-weds hoist sail. Photos courtesy Gary MacMahon

The success of Across Three Oceans and the magnitude of his voyaging achievement had established him as an authority on seamanship, but none of his subsequent books on this and other topics were the same runaway success as that first masterpiece.

Nevertheless he enjoyed reasonable success with accounts of their Mediterranean cruises – one was to the Greek isles – charmingly illustrated by Kitty. But this idyllic phase of their life together was all too brief, by 1934 it was clear that Kitty was unwell, they sailed back to Cornwall, and in 1936 she died at St Mawes, it is believed of leukaemia.

For a year or so Conor O’Brien was something of a lost soul, at one stage living aboard Saoirse while she was laid up in the boatyard at Falmouth. But he’d found another outlet for his writing talents with adventure boys for books, and in all he had five of these published, while also producing another four books on seamanship and yacht equipment.

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 had provided another opportunity. He renewed links with the Royal Naval Reserve and joined the Small Vessels Pool, positioning small craft for the Navy, and filling the role so well that in 1943 he found himself having a fine old time in New York – whose brazen new architecture he adored - involved in the shoreside running of the organisation which made preparations for naval crews to deliver American-provided craft across the Atlantic to the main war zone.

Saoirse while owned by the Ruck family in the 1950s. To simplify sailing, they have fitted a boom to the previousy boomless mainsail.

Saoirse while owned by the Ruck family in the 1950s. To simplify sailing, they have fitted a boom to the previousy boomless mainsail.

But meanwhile he had sold Saoirse in 1941 to an English owner Vincent Ruck, who was to base her between Chichester Harbour in Sussex and Falmouth Harbour in Cornwall, and over the years along that coastline of the south of England, Saoirse was to receive her quota of quiet but approving recognition as the unusual little ship which had pioneered the global route south of the great Capes.

At the end of World War 2 in 1945 and now aged 65, Conor O’Brien returned to Foynes Island for the rest of his days. He kept himself busy building small boats, and sometimes he lived almost like a hermit, but at other times he’d emerge and socialize. He’d been made an Honorary Member of the Irish Cruising Club, and attended some of its dinners. And as he’d kept himself notably fit - if the mood took him in summer, he’d swim with his clothes in a bundle on his head across to Foynes village and stand in the bar there, the water still dripping from him, downing pints of Guinness porter and exchanging banter with the locals.

He died on the island in 1952, and was buried beside his parents at Loghill Church along the mainland County Limerick coast. Saoirse meanwhile remained a much-cherished member of the Ruck family through several generations until the 1970s, when a new owner brought her first to Ireland in 1973, and then went on to Iceland.

Dun Laoghaire in pre-marina days in 1973, and a summee roll coming in from the northeast. Saoirse – on her way to Iceland – is making her first visit to the port since 1925.

Dun Laoghaire in pre-marina days in 1973, and a summee roll coming in from the northeast. Saoirse – on her way to Iceland – is making her first visit to the port since 1925.

Subsequently she took the increasingly popular tradewind route to the Caribbean where she cruised among the islands for several years. But in unsettled weather with hurricanes about in 1979, she came ashore on Negril Beach in Jamaica. At the time it was reported that she was virtually a total loss, but a subsequent visit in recent years to Negril by Gary MacMahon of Limerick – the Conor O’Brien enthusiast par excellence - has resulted in enough artefacts and constructional items from Saoirse being recovered to make a re-build – albeit in a very complete way – a possible project, with enough of the spirit of the ship emerging to be able to state that Saoirse’s soul lives on.

But by the time these items were retrieved from Negril, as any regular reader of Afloat.ie will well know, Gary MacMahon was already well down the long route towards the re-building of Saoirse, but by a somewhat different route. In 1997 he organized the return from the Falkland Islands of the recently de-commissioned Ilen with the simple hope to restoring her to a seaworthy state with all sorts of sailing functions in mind.

Eventually this became the Ilen Project, with the Ilen Boat-Building School as a reconised training organization with proper fully-equipped premises in Limerick, while the hull of Ilen herself came under the care of Liam Hegarty at his boatyard at Oldcourt near Baltimore. For although the original boatyard on the waterfront in Baltimore where Saoirse and Ilen were built in the 1920s had gone into decline, these days Baltimore is a bustling breezy focus of West Cork sailing, one of Ireland’s truly pace-setting sailing centres, and waterfront property has become much too expensive to accommodate a workaday boatbuilding yard.

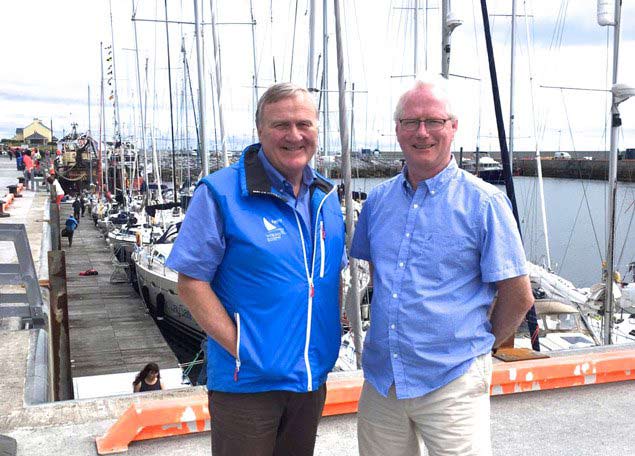

Men with a mission - Liam Hegarty and Gary MacMahon at an early stage of Ilen’s restoration

Men with a mission - Liam Hegarty and Gary MacMahon at an early stage of Ilen’s restoration

There were considerable leaps of faith involved in working towards fulfilling the many and varied potentials of all the strands of the Ilen Project, but throughout it Gary and his team have been given the inspirational support of Brother Anthony Keane of Glenstal Abbey, a personal tower of moral support in trying to achieve objectives some of which are tangible, yet others seem vague in the extreme.

But somehow or other, as the 21st Century settled in, proper work got under way on the restoration of Ilen. Resources have been stretched now and again, and it has taken time, but that’s no harm in that, for now it is one of the best-known ongoing boat restoration projects in the world, almost a matter of pilgrimage.

Meanwhile, however, Gary MacMahon and Liam Hegarty shared the view that the restoration of Ilen would only make sense if, with the experience it provided, they then went on ahead with a new project - the re-building of Saoirse. This was long a vague aspiration, but it became more real after Gary visited Negril Beach, got to know the fascinating community there, and returned with some bits and pieces which provided such a sense of Saoirse that at the Baltimore Woodenboat Festival in 2015, he and Liam found themselves in complete agreement that somehow or other, Saoirse would sail again.

Ilen (top) as she is this week after the restoration and (bottom) as she was at her launching day in 1926. Photos courtesy Gary MacMahon

Ilen (top) as she is this week after the restoration and (bottom) as she was at her launching day in 1926. Photos courtesy Gary MacMahon

Their faith was so total, and supported of course by Brother Anthony, that they started ordering timber in order to have secured a properly seasoned stock by the time work on the Ilen had been completed. But it was all a matter of faith until September 2016, when Fred Kinmonth came into the ancient building – it has several names, in the yard they simply call it “The Top Shed” – where Ilen was being restored. With traditional boat-building under way, it is a place of unique serenity, and the entire scene spoke to Fred Kinmonth in a special way.

Ilen (top) immediateoy before the restoration job began, and as she is now (bottom).

Ilen (top) immediateoy before the restoration job began, and as she is now (bottom).

He’s of a high-powered professional family with cherished links to West Cork – as long ago as 1966, he was cruising from Union Hall to Valentia in the family’s Tyrrell-designed-and-built sloop Sinloo. But while most Kinmonths have gone into medicine, Fred went into corporate law, and he has had a stellar career in Hong Kong and right across the Far East.

He is very much into sailing in Hong Kong and is personally linked to a series of successful boats called Mandrake (the current Mandrake III is designed in Ireland, a Mark Mills 41), while he’s also a longtime member of the Royal Hong Kong Yacht Club and will be among those involved when Hong Kong welcomes the Volvo Ocean Race fleet in a few days time.

Fred Kinmonth’s Mark Mills-designed Mandrake III.

Fred Kinmonth’s Mark Mills-designed Mandrake III.

He enjoys life at the sharp end, indeed he thrives on it. But if he feels his batteries need re-charged, he puts in time in his spiritual home of West Cork. It was in this quietly thoughtful frame of mind in September 2016 that he looked into the top shed at Oldcourt and inhaled that Ilen restoration atmosphere. By the time he was returning to Hong Kong, it had been decided that Saoirse would be re-built for Fred Kinmonth, and the worked started this week.

All of which goes some way to explain why, as the rest of us wound down towards Christmas except for those heroes gearing up for the Rolex Sydney Hobart Race, down Baltimore way there was a special buzz of activity at Oldcourt around Ilen. The shipwrights’ work had been finished, the deck and houses had been sealed, most future work in joinery would be inside the hull, so it was time to move and vacate the shed for work to begin on the re-build of Saoirse.

The result is that in the depths of winter, we have had an inspiring glimpse in daylight of the transformation which has been worked on Ilen. Not only is it something which provides great expectations of what the re-built Saoirse will look and feel like, but it is very encouraging to continue progress towards Ilen’s new role as a Marine Learning Environment, a sailing schoolroom which will bring the message to schools and communities.

Ilen as she will look when she undertakes her new role as a Marine Learning Environment.

Ilen as she will look when she undertakes her new role as a Marine Learning Environment.

As for the future of Saoirse, this morning it is enough to know that the re-build is happening, but for the moment it is behind closed doors. You’ll note that as soon as Ilen was out of the shed, the great doorway in the gable end through which she had exited was closed off. Setting up to re-build Saoirse properly to a contract time is a serious business, and Liam Hegarty and his team have deserved to be left in peace during this key week.

The work moves on. Ilen is out of the shed, while inside the preliminaries for the re-build of Saoirse are under way. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The work moves on. Ilen is out of the shed, while inside the preliminaries for the re-build of Saoirse are under way. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The significance of Saoirse and her re-build contributes in unexpected ways to an awareness and maybe an understanding of our island’s complex past. The first major recognition that Conor O’Brien and Saoirse achieved was the award of the Royal Cruising Club’s Challenge Cup – the world’s senior cruising award – in 1923 while the voyage was under way. He received it again in 1924, and in 1925.

The RCC was at the very heart of the British maritime establishment. Yet despite his known gun-running voyage, the RCC had admitted O’Brien as a member in 1919. That may seem to stretch tolerance. But even more bizarre is the fact that O’Brien was proposed for membership by Frank Gilliland, a member from the north coast of Ireland, and seconded by Erskine Childers, who had joined the RCC when he started working in England in 1895.

However, by the time Saoirse departed on her voyage in June 1923, Frank Gilliland had since 1921 been Commander Frank Gilliland, Aide de Camp to the Governor of the newly-established Northern Ireland. And Erskine Childers, having come out in armed opposition to the treaty establishing the Irish Free State and the partition of Northern Ireland, had in November 1922 been executed by a firing squad of the Government of the new Irish Free State.

Through all this extraordinary turmoil and mixing of allegiances, Conor O’Brien and the Saoirse sailed on with their exceptional voyage. It was the great cruising authority Claud Worth, the adjudicator of the RCC awards, who best put Saoirse’s achievement into perspective, and explains why the work which started this week in Oldcourt is so important. Worth commented:

“Anyone who knows anything of the sea, following the course of the vessel day by day on the chart, will realize the good seamanship, vigilance and endurance required to drive this little bluff-bowed vessel, with her foul uncoppered bottom, at speeds of from 150 to 170 miles a day, as well as the weight of wind and sea which must sometimes have been encountered.”

Amen to that.

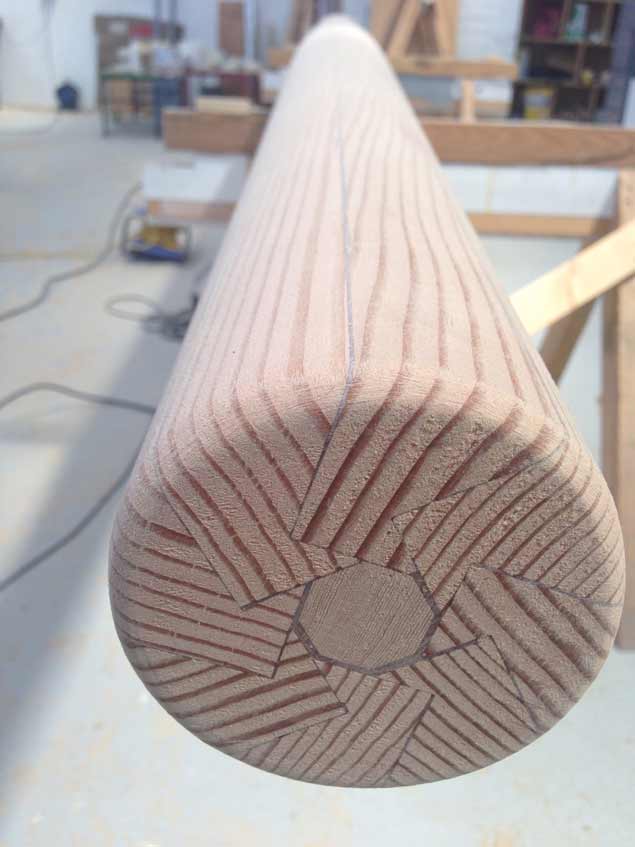

Historic Ketch Ilen’s Rig Restoration Takes Shape with Indoor Comfort

When we recall the exposed conditions in which some coastal boat and ship-builders had to work in the days when life and labour were cheap, and health and safety were considered more important for thoroughbred animals than for workers, then it has to be said that that the spar-makers of Limerick assembling the rig for the restoration of the 1926-built 56ft ketch Ilen are creating their finished sections in some comfort in the Ilen Boatbuilding School writes W M Nixon

In its way, each spar has emerged as a work of art. Photo: Gary MacMahon

In its way, each spar has emerged as a work of art. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Spar-making is a mixture of traditional and newer techniques. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Spar-making is a mixture of traditional and newer techniques. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The gaff jaws may have to be used for rugged work, but that’s no reason why they shouldn’t be assembled with style Photo: Gary MacMahon

The gaff jaws may have to be used for rugged work, but that’s no reason why they shouldn’t be assembled with style Photo: Gary MacMahon

The Ilen Boat-building School in Limerick has sufficient space to lay out the complete mainmast with topmast, gaff and boom – shipwright James Madigan provides a sense of scale.

The Ilen Boat-building School in Limerick has sufficient space to lay out the complete mainmast with topmast, gaff and boom – shipwright James Madigan provides a sense of scale.

But though they have a decent amount of space and the benefits of modern equipment, the fact that the Douglas Fir for the new spars has been donated from the stores of the much-lamented Asgard II puts an even greater onus on the team to produce work of world class.

That said, the temptation to stray into the realms of classic yacht style is ever-present when you have wood and facilities of this quality. But it has always to be remembered that Ilen is the sole surviving Irish-built sailing trader of this size and type. Thus Project Director Gary MacMahon has to ensure that the work remains true to traditional workboat style rather than veering towards anything too ornamental.

Engineering the connection of the topmast and mainmast at the hounds, Pete Speake (left) working with James Madigan (lower right) Photo: Gary MacMahon

Engineering the connection of the topmast and mainmast at the hounds, Pete Speake (left) working with James Madigan (lower right) Photo: Gary MacMahon

The test assembly of mainmast and topmast. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The test assembly of mainmast and topmast. Photo: Gary MacMahon

But as the simple functionality of each spar and fitting which has been made has its own inherent beauty, ornamentation would be superfluous, and as our gallery of photos reveals, in its way each piece is a work of art.

An early stage in creating the senior and junior mast partners, crafted by Matt Dirr Photo: Gary MacMahonAn early stage in creating the senior and junior mast partners, crafted by Matt Dirr Photo: Gary MacMahon

An early stage in creating the senior and junior mast partners, crafted by Matt Dirr Photo: Gary MacMahonAn early stage in creating the senior and junior mast partners, crafted by Matt Dirr Photo: Gary MacMahon

The senior and junior mast partners completed, one for the mainmast, the other for the mizzen. Photo: Gary MacMahon

The senior and junior mast partners completed, one for the mainmast, the other for the mizzen. Photo: Gary MacMahon

At Liam Hegarty’s boatyard in Oldcourt near Baltimore, 180 kilometres from Limerick, the mainmast partner is offered up aboard ship – and fits to perfection. Photo: Gary MacMahon

At Liam Hegarty’s boatyard in Oldcourt near Baltimore, 180 kilometres from Limerick, the mainmast partner is offered up aboard ship – and fits to perfection. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Conor O’Brien Ketch Ilen Starts to Feel Like a Living Ship Again

The process of transforming the restored hull and deck of the 1926-built 56ft Conor O’Brien historic ketch Ilen into a living ship continues writes W M Nixon. The programme is co-ordinated and combined between the Ilen Boatbuilding School in Limerick, where they’re busy on the benches making or re-conditioning many items of gear and equipment, and in and around the ship herself with Liam Hegarty in Baltimore in West Cork. There, it finally all comes together, and last weekend provided a real sense of a new stage reached in the project.

James Madigan in the Ilen School in Limerick with a workshop-mockup of the traditional steering arrangement, including the helmsman’s footwell which has since been fitted in the ship. Photo: Gary McMahon

James Madigan in the Ilen School in Limerick with a workshop-mockup of the traditional steering arrangement, including the helmsman’s footwell which has since been fitted in the ship. Photo: Gary McMahon

In Oldcourt, the hydraulic steering actuator – renovated in Limerick – is ready for final fitting to the rudder stock. Photo: Gary McMahon

In Oldcourt, the hydraulic steering actuator – renovated in Limerick – is ready for final fitting to the rudder stock. Photo: Gary McMahon

Lights gleamed from below where the accommodation is being created, and traditional timberwork shone with warmth in the homely setting of The Old Cornstore on the banks of the Ilen River. This much-loved waterway runs from Skibbereen down towards Baltimore to provide the home training waters of some of Ireland’s greatest contemporary rowers, as well as a sheltered setting for the always-fascinating boatyard complex.

The unique atmosphere of this special boat-building location is more cherished than ever. It had been feared that the Old Cornstore and the surrounding Oldcourt Boatyard were right in the path of serious damage from Storm Ophelia three weeks ago. But although a gust of 191 km/h was recorded out at the Fastnet Rock, and 135 km/h was logged at Sherkin Island just across from Baltimore, Oldcourt came through relatively unscathed. The place leads a charmed life.

Starting to look like a ship again. Snug under the Ophelia-surviving vintage roof in the Old Cornstore at Oldcourt, Ilen is now giving a much better impression of what she’ll be like to be aboard at sea. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Starting to look like a ship again. Snug under the Ophelia-surviving vintage roof in the Old Cornstore at Oldcourt, Ilen is now giving a much better impression of what she’ll be like to be aboard at sea. Photo: Gary MacMahon

As for the ketch’s restoration project, a stage had been reached where teams from both Ilen Boatbuilding centres could usefully combine forces last Saturday to clear up the boat from end to end the better to appreciate what has been achieved, and to appraise what still needs to be done. In comparing the photos below which show Ilen as she was when last in commission at the Glandore Classics of 1998, and as she was on Saturday, there’s no doubting that the spirit of the old ship is being re-born.

Aboard Ilen as she was in 1998 at Glandore (left) and on deck last Saturday in Oldcourt (right). Photo: Gary MacMahon

Aboard Ilen as she was in 1998 at Glandore (left) and on deck last Saturday in Oldcourt (right). Photo: Gary MacMahon

As is the way with restorations, it’s intriguing to learn how various specialist items of equipment have been retrieved or saved. In a city with a metal-working tradition like Limerick, there’s an instinctive appreciation of the quality of the workmanship which has gone into the rigging hardware for shrouds and masts alike.

Some of Ilen’s rigging hardware, in a time-honoured style much-appreciated in a city with a metal-working tradition. Photo: Gary McMahon

Some of Ilen’s rigging hardware, in a time-honoured style much-appreciated in a city with a metal-working tradition. Photo: Gary McMahon

And although we’ve shown photos of the Ilen dead-eyes made from lignum vitae before, there’s something so fascinating about this densest of timbers (in this case “contributed from a former shipyard in Cork”) that a second or third look is surely justified, appreciating them as works of art shaped in the Ilen school in Limerick by Matt Dirr.

Matt Dirr crafting dead-eyes in the Ilen School. Photo: Gary McMahon Photo: Gary MacMahon

Matt Dirr crafting dead-eyes in the Ilen School. Photo: Gary McMahon Photo: Gary MacMahon

Dead-eyes finished and varnished. There is an eternal fascination in lignum vitae, the “wood of life”, one of the densest timbers in the world. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Dead-eyes finished and varnished. There is an eternal fascination in lignum vitae, the “wood of life”, one of the densest timbers in the world. Photo: Gary MacMahon

As for that rather choice bronze fairlead, we immediately fired back an enquiry to Ilen School Director Gary McMahon as to who made it, for it too is a work of art. The answer is he doesn’t know who made it, but having worked in metal himself he has long been an inveterate collector of special items which would otherwise be on their way to the scrapyard, and this came off an old vessel which was being dismantled in Limerick. Now, thanks to the Ilen Project, it will once again sail the seas.

A proper little work of art – a bronze fairlead, salvaged from a breaker’s yard many years ago. Photo: Gary MacMahon

A proper little work of art – a bronze fairlead, salvaged from a breaker’s yard many years ago. Photo: Gary MacMahon

Unlike the fairlead, this deck eyebolt is new-made, but it wouldn’t look out of place as a piece of functional art on a modern gallery. Photo: W M Nixon

Unlike the fairlead, this deck eyebolt is new-made, but it wouldn’t look out of place as a piece of functional art on a modern gallery. Photo: W M Nixon

2017 – A Very Irish Sailing Season

While sailing is now a year-round interest, and for many a year-round activity too, the notion of a traditional season is natural for anyone who lives in Ireland. Admittedly, there are times when we seem to be experiencing the four annual climatic seasons in just one day. But this sense of a seasonal change, and the appropriate alterations in activity which accompany it, are in our genetic makeup. And though marinas and the Autumn Leagues which they facilitate have pushed the season’s end back to the October Bank Holiday Weekend, for many, that’s it. It’s finally time for boats to be rested and energies deployed in other ways. W M Nixon reflects on highlights of the year.

These times we live in, they tend to emphasise big events – celebrity happenings you might call them – and our perceptions of a season past may be skewed by how the major fixtures played through. But your true Irish sailing season has at its core the classic club programme from April to October, with its plethora of weekend and weekday evening events. If you want to sense the beating heart of our sailing, you have to take the pulse of this local and club scene.

We know it’s not for everyone. Some dinghy crews only emerge for major regional and national championships. But week in, week out, it’s the regular local sailing, from the smallest club right up to the majestic programme of Dublin Bay Sailing Club, which sets the tone for the majority of sailors.

Week in, week out, Dublin Bay Sailing Club provides a comprehensive programme of local racing from the end of April until the end of September, and it has been successfully doing so since 1884. Here the club's Beneteau 31.7s, one of DBSC's largest one design keelboat fleets negotiate a weather mark at the class championships Photo David O’Brien/Afloat

Week in, week out, Dublin Bay Sailing Club provides a comprehensive programme of local racing from the end of April until the end of September, and it has been successfully doing so since 1884. Here the club's Beneteau 31.7s, one of DBSC's largest one design keelboat fleets negotiate a weather mark at the class championships Photo David O’Brien/Afloat

And for those who sailed regularly all through the time-honoured season, it has to be admitted that weatherwise, we experienced a very mixed bag. As we shall see, there were brief periods of good weather which blessed some events. But in any case, one dyed-in-the-wool cub sailor firmly told us that as far as he was concerned, it was a very good season.

“For sure, there was rain and wind,” he said. “But we need wind for sailing. If you get a long period of rain-free weather, the evenings are likely to be wind-free as well. Frankly I’d rather get a good race in rain than sit becalmed on a perfect summer’s evening. But as we’re an east coast club, we often get that east coast effect of Atlantic weather without Atlantic rain, which is ideal for club racing. By and large, it has been a good sailing season, and race management seems to be improving all the time. So 2017 is going to go down as a good year for club sailing, but only a very average year for sunshine”.

As for Irish sailing’s national structure, inevitably there’s a clashing of events. There is only a finite number of weekends available at peak season when different big ticket regattas and championships hope to be staged, but as well, each club and area quite rightly expect to bring prestigious fleets to its part of Ireland.

However, in 2017 there was increasing emphasis at official club level on making sailing fun again. We’d begun to take it too seriously, something reinforced by the grim years of the recession, and then the winning in 2016 of Annalise Murphy’s Silver Medal at the Olympics in Rio.

Olympic Silver Medallist Annalise Murphy led the way in signalling a change of mood for 2017 after the seriousness of her 2016 campaign towards success in Rio. In the early part of the season, she concentrated on the International Foiling Moth, and in this 223-strong fleet at the Worlds on Lake Garda in May, she became the Women’s World Champion. She is currently on a completely different direction for ten months on the Volvo Ocean Race as a crewmember on the One-Design Volvo Ocean 65 Turn the Tide on Plastic

Olympic Silver Medallist Annalise Murphy led the way in signalling a change of mood for 2017 after the seriousness of her 2016 campaign towards success in Rio. In the early part of the season, she concentrated on the International Foiling Moth, and in this 223-strong fleet at the Worlds on Lake Garda in May, she became the Women’s World Champion. She is currently on a completely different direction for ten months on the Volvo Ocean Race as a crewmember on the One-Design Volvo Ocean 65 Turn the Tide on Plastic

Of course the winning of Annalise’s medal was a matter for fun-filled celebration once it had happened, but the buildup to it was deadly serious, and that affected the tone of the national sailing mood in every area. But with the Medal in the bag, 2017 could reasonably expect to have a lighter mood, and this in turn helped us to adjust to an over-crowded programme, as crews could plan on a series of campaigns which balanced between serious events which provided proper championship results of national significance, and events which officially claimed to be providing everyone with a good time, even if some crews raced with deadly seriousness.

Either way, so much was going on that a review like this can only hope to give an impression of the season rather than a detailed analysis, but we’ll try to give it a comprehensible shape by listing the main events of Irish interest at home and abroad under either the “serious” or “fun” categorisations:

March/April: Intervarsity Championships – serious, UCD selected to represent Ireland

April: Irish Sailing Youth Pathway Nationals, Ballyholme - serious (and impressive), Ewan McMahon the star, Rush SC prominent in success

The hyper-busy J/109 Mojito managed a hard-fought overall win in the ISORA Championship, successful participation in the Rolex Rastnet Race, and a second place in the Dun Laoghaire to Dingle Race.

The hyper-busy J/109 Mojito managed a hard-fought overall win in the ISORA Championship, successful participation in the Rolex Rastnet Race, and a second place in the Dun Laoghaire to Dingle Race.

April: Season-long ISORA Championship get under way, several venues – inevitably serious. In due course, J/109 Mojito (Peter Dunlop & Vicky Cox, Pwllheli SC) has very close overall win – despite taking time out to do the Fastnet

May: Scottish Series at Tarbert– serious, Pat Kelly’s J/109 Storm and Stephen Quinn’s J/97 Lambay Rules top their classes.

June: Howth Lambay Weekend – Fun

It could be a remote part of the West Coast, but Howth Yacht Club’s annual Lambay Race is a reminder that Ireland’s least-spoilt coastline is on an East Coast island. Photo courtesy HYC

It could be a remote part of the West Coast, but Howth Yacht Club’s annual Lambay Race is a reminder that Ireland’s least-spoilt coastline is on an East Coast island. Photo courtesy HYC

June: ICRA Nationals Royal Cork – probably the most serious of them all. John Maybury’s J/109 Joker 2 RIYC), Ross MacDonald’s X332 Equinox (HYC), and Paul Gibbons’ Anchor Challenge (RCYC) win the three main classes.

Rob O’Leary racing the Dubois 36 Dark Angel from South Wales to class success in the ICRA Nats at Crosshaven. Photo: Robert Bateman

Rob O’Leary racing the Dubois 36 Dark Angel from South Wales to class success in the ICRA Nats at Crosshaven. Photo: Robert Bateman

Paul O’Higgins’ JPK 10.80 Rockabill VI shortly after the start of the very tough Dun Laoghaire to Dingle Race, which she won, while a sister-ship Bogatyr was also winner of the likewise rough 608-mile Rolex Middle Sea Race in late October. This photo goes some way to revealing the reason for the JPK 10.80’s success – she is only 35ft LOA, yet you’d think you’re looking at a significantly larger boat. Photo: David O’Brien/Afloat.ie