Displaying items by tag: Dublin Bay 24

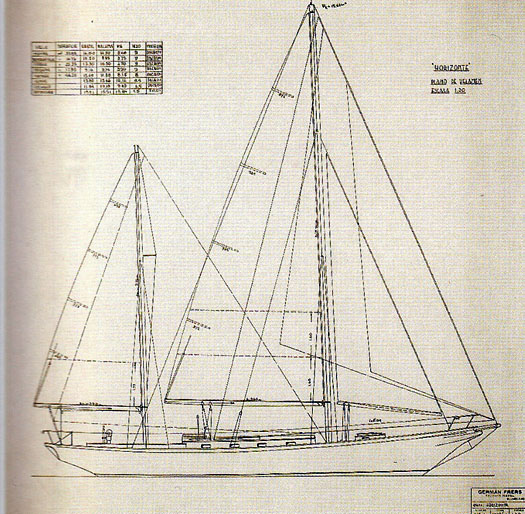

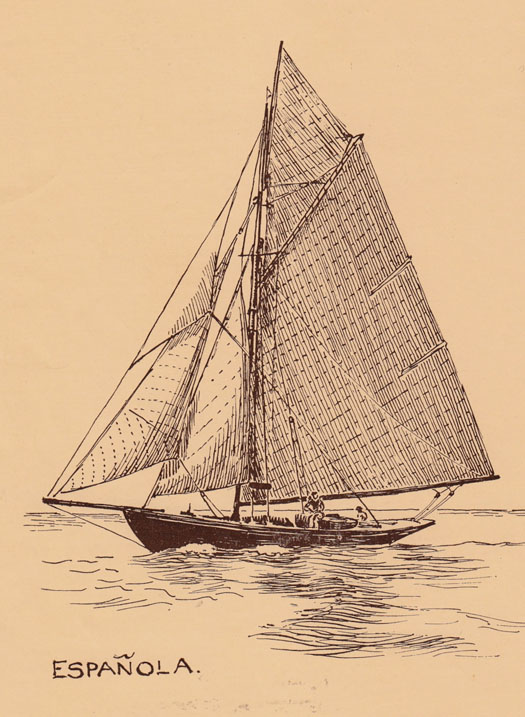

The concept of the Dublin Bay 24, envisaged as a 24ft waterline 37ft LOA Bermuda-rigged racer-cruiser, was first suggested in 1934 at a Committee Meeting of the innovative yet “homeless” Royal Alfred YC in Dun Laoghaire by the owner-skipper of the DB 21 Garavogue, Gordon Campbell aka Lord Glenavy. Yet by the time the idea began to gain traction in 1937, it had been taken under the wing of the Dublin Bay Sailing Club, as too – though much more recently - has the RAYC itself.

Dublin Bay 24s racing at their Golden Jubilee Regatta in 1997. The class continued racing – though in growing need of restoration – until September 2004. Photo: W M Nixon

Dublin Bay 24s racing at their Golden Jubilee Regatta in 1997. The class continued racing – though in growing need of restoration – until September 2004. Photo: W M Nixon

But though the first of the DB24 boats – in all, eight were to be built in Scotland – came under construction at designer Alfred Mylne’s boatyard on the Isle of Bute in the Firth of Clyde by late 1938, the total leisure-boat construction shutdown of World War II (1939-1945) meant they didn’t finally race as the premier Dublin Bay OD class until 1947.

RORC OVERALL WIN

There were never more than seven of them racing in Dublin Bay, as Periwinkle stayed on in Scotland. But they gave great service in many areas, providing excellent inshore racing, and proving themselves in offshore racing in 1963 when Stephen O’Mara’s Fenestra RIYC, skippered by Arthur Odbert, won that year’s stormy RORC Irish Sea Race overall.

Party time – the DB24s celebrate their Golden Jubilee at the Royal Irish YC in 1997. Photo: W M Nixon

Party time – the DB24s celebrate their Golden Jubilee at the Royal Irish YC in 1997. Photo: W M Nixon

The modest skipper claimed that success came because the boat was so relatively narrow and heavy with low freeboard that she simply went straight through everything the Irish Sea in a Force 9 could throw at her, rather than trying to climb laboriously over it. And anyway, he and his notably bibulous crew - with himself setting the pace - had so indulged themselves at the pre-race party in the Royal St George that there wasn’t a shilling left in the ship’s kitty, so retiring into some other port – as several other boats were already doing - would have been pointless, when they knew fresh credit could soon be negotiated in their Dun Laoghaire club if they could just manage to batter their way back to the finish line there.

DB 24s at the RIYC in 1997 – Periwinkle is on left. Photo: W M Nixon

DB 24s at the RIYC in 1997 – Periwinkle is on left. Photo: W M Nixon

CRUISING ACHIEVEMENT

As for cruising, Rory O’Hanlon’s Harmony (RStGYC) and Ninian Falkiner’s Euphanzel (RIYC) were both awarded major trophies of the Irish Cruising Club, while many shorter ventures continued to reveal the boats’ versatility.

But by the time their Golden Jubilee came around in 1997, just five were regularly based in the bay. Vandra had been wrecked when driven ashore in a storm squall with sail and rigging failure. And the Connacht-based owner of Zephyra had fallen out with the DB24 class in particular, and Dublin Bay Sailing Club in general, to such an extent that he went off in a high dudgeon with the boat in tow on a road trailer, and had reputedly hidden her at his castle somewhere in far Mayo.

FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY

Nevertheless when the 50th Anniversary came up in 1997 with a Woodenboat Regatta in Dublin Bay, Periwinkle came south from Scotland to ensure that six boats were actively racing. But while the sport was great, it was clear that five decades of a very active life had taken their toll on the boats, and most of them needed major restorations with a dedicated classic boat builder.

In Dr Rory O’Hanlon’s ownership, the DB24 Harmony was noted as much for her cruising as her racing. Photo: Rex Roberts

In Dr Rory O’Hanlon’s ownership, the DB24 Harmony was noted as much for her cruising as her racing. Photo: Rex Roberts

Yet it was 25th September 2004 before the class had their last official race with Dublin Bay SC. And by this time, an ambitious scheme was starting to develop whereby one central organisation would buy up all the boats, including anything that remained of Vandra. The plan was to have them restored by recognized international classic specialists to become the Royal Alfred One Designs, available for fleet hire for racing as a special attraction with a new sailing-orientated resort hotel being planned on the French Riviera.

“FINDING ZEPHYRA”

In time, all the existing boats including Periwinkle had been bought up by the new grouping except for Zephyra, and were assembling in Dublin to be moved to classic yards, mainly in France. As for Zephyra, “she’s in Mayo” made for a very wide search area. But it so happened that I was walking our little dog out the back of a castle-hotel in Mayo early in the summer of 2007, and there in a corner, barely showing above an overgrown wall, was a tiny glimpse of a boat of interest which proved to be Zephyra, by now rapidly disappearing into the undergrowth.

The first glimpse of Zephyra in Mayo. Photo: W M Nixon

The first glimpse of Zephyra in Mayo. Photo: W M Nixon

2007 being peak year for the Celtic Tiger, the Dublin team had her snapped up and with her sister-ships in Dublin just as quickly as possible. But the ultra-boom years of 2007-2008 were concluded with the global financial crash, and that made many dreams, especially those in the style of a restored Dublin Bay 24 class emerging re-born as the exquisite and highly fashionable Royal Alfred One Designs, into an unattainable ambition for the foreseeable future.

CLASSIC RESTORATION

Yet gradually use was made of the available boats on an individual basis, and the superbly-restored Perwinkle eventually returned from France to Dun Laoghaire and is now in the ownership of David Espey to provide a perfect example of what genuine classic restoration should be like.

The Dublin Bay 24 Zephyra as she was in 2007, “discovered” in an increasingly overgrown state in the corner of a castle yard in Mayo. Photo:W M Nixon

The Dublin Bay 24 Zephyra as she was in 2007, “discovered” in an increasingly overgrown state in the corner of a castle yard in Mayo. Photo:W M Nixon

Arandora was also restored in Brittany and she is thought to be still in France, while somehow Zephyra found her way to the Apprenticeshop in Rockland on the mid-Maine coast in the US, where the word was that a properly-built Dublin Bay 24 is such a perfect example of the ideal size and type for teaching real boat-building that Zephyra’s fate might consist of a Groundhog Day existence of being re-built, and then un-built, and then re-built again and again for ever and ever.

“The ideal size to teach classic boat-building” – Zephyra being re-born in the Apprenticeshop in Maine

“The ideal size to teach classic boat-building” – Zephyra being re-born in the Apprenticeshop in Maine

Not so. David Espey has just had word that the completely restored Zephyra is to be launched at Rockland on June 28th 2024. I’ve a feeling there’ll be an interesting selection of classic boat and Dublin Bay enthusiasts there to witness the next stage in this extraordinary journey from a Mayo castle’s overgrown backyard to the fascinating waters of Maine.

THE AUSTRALIAN SISTER

And the story of this remarkable design, to a concept well ahead of its time when Gordon Campbell first outlined it in 1934, has even more to it. A ninth Dublin Bay 24 was built in Sydney, Australia in 1948. Over the years, Wathara was updated even unto a cute little retroussé transom and a masthead rig. But a new owner, Damien Brassel, has taken her in hand, he is determined to restore her to true Dublin Bay 24 status, and there has been in close contact with David Espey to ensure he’s getting it right.

The “Southern Sister” – the modernized DB24 Wathara in Sydney Harbour. She is now in process of being restored to the original design

The “Southern Sister” – the modernized DB24 Wathara in Sydney Harbour. She is now in process of being restored to the original design

Dublin Bay’s Definitive One Designs Provide Ideal Projects For International Boat-Building Schools

The recent spell of hyper-sunny weather was a reminder of the time we stumbled upon the “lost” Dublin Bay 24 Zephyra while searching for shade to walk our little dog around the back of a castle in Mayo. The elegant counter of a classic yacht was glimpsed above an overgrown wall around a small yard. And there - under an assortment of covers and in danger of becoming completely overgrown – was a classic beauty that could only be Zephyra.

For we knew that while almost all the Dublin Bays 24s - built to an Alfred Mylne design of 1938 and first raced as a class at Dun Laoghaire in 1947 - had been gathered for an ambitious restoration project, Zephyra had last been seen some years earlier headed west by road, her strong-minded owner having fallen out with Dublin Bay sailing in general, and the DB24 Class in particular.

The “lost” Zephyra as found in Mayo nearly twenty years ago. Photo: W M Nixon

The “lost” Zephyra as found in Mayo nearly twenty years ago. Photo: W M Nixon

So here she was, at last, hidden away on that day of unimaginably bright sunshine in Connacht. And here she stayed - but now closely if secretly monitored - until the Grim Reaper changed the dynamics of the situation, such that overnight - or so it seemed – Zephyra was back in Dublin with a minimum of fuss and fanfare.

But with the economic crash of 2009, ambitious plans for the re-birth of the DB24s as a smart restored class went by the board. However, in the long run, there’s very little about boats that doesn’t go completely to waste, and so long as you still have the original external ballast keel of lead or cast iron, what looks to a casual observer like the building of a new boat can be classified as a re-build or even – if some of the original timber remains – as a restoration.

Dublin Bay Water Wags in tight racing. With more than fifty boats registered as valid for racing, the use of the design as a boat-building training project is given extra purpose. Photo: W M Nixon

Dublin Bay Water Wags in tight racing. With more than fifty boats registered as valid for racing, the use of the design as a boat-building training project is given extra purpose. Photo: W M Nixon

Either way, it’s grist to the mill of boat-building schools, and this is where the Dublin Bay One Designs hit the spot. As the birthplace of One Design Racing ever since the advent of the first Water Wags in 1887, it has brand recognition to die for. As a remarkably settled, long-established and cohesive sailing community, it has the continuity for the class rules, designs and specifications to be properly codified, and faithfully recorded and maintained such that – when a new build is being contemplated – the boat is validly re-created.

Thus, in historic international One-Design terms, appending that “Dublin Bay” tag is gold standard. You become acutely aware of this when some purchaser overseas of what is reputedly “a Dublin Bay OD” has to be told - as gently as possible - that she isn’t.

THE DUBLIN BAY PREMIUM

All this means that in today’s boat-building schools, where many courses are based on the process of un-building an old boat and then re-creating her anew on the original ballast keel, Dublin Bay ODs are at a premium, as they provide a comprehensive range of boat within a manageable size range.

Gold Standard. Steve Morris of Kilrush with the “impossibly beautiful” hull of the restored Dublin Bay 21 Geraldine. Photo: Mark Sweetnam

Gold Standard. Steve Morris of Kilrush with the “impossibly beautiful” hull of the restored Dublin Bay 21 Geraldine. Photo: Mark Sweetnam

Another aspect is that in the smaller sizes, such as the Water Wags, the boats can be usefully built completely from new in order to join the Bay’s most active class, and they’ve been built in Europe by schools as far away as Bilbao. And from across the bay and beyond the Howth peninsula, the Howth 17s have provided the demand both for re-builds and new builds in schools in France as the class in its 125th Anniversary year is racing more keenly than ever.

But move up the size scale a little more, and thanks to Hal Sisk and Fionan de Barrra, the re-birth of the Dublin Bay 21 class has provided education in a different direction, with Steve Morris of Kilrush using these beautiful craft to teach a new generation of boat-builders how multi-skin epoxy construction looks even better in a classic hull.

As a very actively-raced class celebrating its 125th Anniversary in 2023, the Howth 17s have added attraction as a boat-build learning project. Photo: W M Nixon

As a very actively-raced class celebrating its 125th Anniversary in 2023, the Howth 17s have added attraction as a boat-build learning project. Photo: W M Nixon

Beyond that, however, the Dublin Bay 24 is getting into a size scale where manageability is more problematic, and so far, only David Espey’s Periwinkle has returned from France in fully restored form.

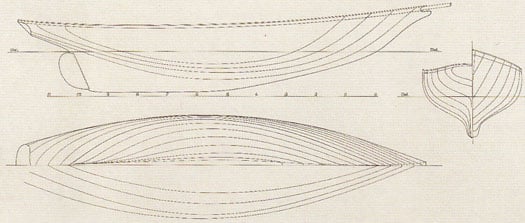

Yet there’s no getting away from the fact that a re-born Dublin Bay 24 provides perfect subject matter for a boat-building school. This is classic construction with the Alfred Mylne imprimatur. The hull is sufficiently large for several people to work at it at the same time without getting in each other’s way, yet it necessarily involves much useful and highly-educational team effort.

Zephyra in The Apprenticeshop. With suitable premises like this, the Dublin Bay 24 is of manageable size while being large enough to facilitate real teamwork

Zephyra in The Apprenticeshop. With suitable premises like this, the Dublin Bay 24 is of manageable size while being large enough to facilitate real teamwork

Zephyra’s planking progresses in Maine. It’s remarkable to think that this elegant and fine-lined hull design, just 24ft on the waterline, was overall winner of a RORC Race in 1963

Zephyra’s planking progresses in Maine. It’s remarkable to think that this elegant and fine-lined hull design, just 24ft on the waterline, was overall winner of a RORC Race in 1963

Kevin Carney’s Apprenticeshop boat-building school at Rockland in Maine is where Zephyra has been in the key role. Although the pupils of all ages sign on for a two year course, they reckon that the fully-utilised re-building of a Dublin Bay 24 takes a little longer than that.

Either way, it means that people in distant places have now joined the many in Ireland who reckon that the Dublin Bay 24 was one of Alfred Mylne’s most beautiful creations. Yet in studying this elegant and fine-lined thoroughbred, it takes an effort to remember that it was a sister ship, the DB24 Fenestra, which in 1963 provided Alfred Mylne with his only overall win in a RORC event, the storm-tossed Irish Sea Race. The Dublin Bay 24 is a classic in every way.

Getting near the end of the line. Dublin Bay 24s in their Golden Jubilee Race in 1997. Within five years, they were thought of as sufficiently “worn out” for regular racing to cease. Photo: W M Nixon

Getting near the end of the line. Dublin Bay 24s in their Golden Jubilee Race in 1997. Within five years, they were thought of as sufficiently “worn out” for regular racing to cease. Photo: W M Nixon

Dublin Bay’s Sensible Yacht Design Choices Are Imitated Worldwide

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then Dublin Bay sailors can walk very tall indeed. Their selections over the years of various One Design concepts have spread worldwide among discerning owners, who appreciated that the Dublin Bay sailors’ ability to coax designs out of international names such as William Fife III and Alfred Mylne provided ready access to genuine gold standard plans for construction anywhere in the world by capable shipwrights.

And in truth it didn’t stop with the boat designs for DBSC by Fife and Mylne in the 1890s and early 1900s. The 1900-version of the world’s 1887-founded oldest One-Design class, the 14ft Dublin Bay Water Wags by Dun Laoghaire boatbuilder J E Doyle’s talented daughter Maimie, was the blueprint for an able boat which was taken up elsewhere, some of them in very distant sailing centres.

The Maimie Doyle Water Wag design of 1900 spread from Dun Laoghaire to North Wales and other much more distant sailing centres. They are seen here racing on Lough Ree.

The Maimie Doyle Water Wag design of 1900 spread from Dun Laoghaire to North Wales and other much more distant sailing centres. They are seen here racing on Lough Ree.

In those days, female yacht designers were rare, and in the claustrophobic world of Kingstown sailing, Doyle used to get mocked for the fact that his daughter created elegant designs from his own original rough ideas. In fact, he was so riled by it all that he refused to allow the designs to be published unless they were credited to J E Doyle. But sailing journos were as contrary a bunch in those days as they are now, so they always found a way of letting everyone know that it was Maimie’s creation, regardless of what was said in the official records.

Thus when one of our secret agents in Australia - Lee Condell, originally of Limerick – came up with the news that the 52ft Granuaile of 1905 Dun Laoghaire origins was up for sale Down Under, all bells rang and all lights flashed to remind us that this was one of Maimie Doyle’s finest creations.

A masterpiece. The lines of the currently Australian-based 52ft Granuaile, designed in 1905 by Maimie Doyle and built by her father J E Doyle in Dun Laoghaire

A masterpiece. The lines of the currently Australian-based 52ft Granuaile, designed in 1905 by Maimie Doyle and built by her father J E Doyle in Dun Laoghaire

But a recent search for something else altogether revealed that in 1948, a shrewd Australian owner secured the Alfred Mylne plans from 1938 for the Dublin Bay 24, and the result was Wathara. And in her early days, Wathara was much the same as the standard DB24, as spectacularly revealed in this photo of the Martin brothers with Adastra doing a spot of showing off as they head seaward into the gusty westerly curling round the end of the West Pier in Dun Laoghaire.

The DB24 Adastra showing all she’s got as the Martin brothers drive her through a gust of wind curling round the end of Dun Laoghaire’s West Pier.

The DB24 Adastra showing all she’s got as the Martin brothers drive her through a gust of wind curling round the end of Dun Laoghaire’s West Pier.

But over the years, Wathara has been up-dated with mods, including a cute little retroussé transom which might well have been inspired by the 12 Metres of Australia’s great America’s Cup-challenging days. The coachroof has been replaced and lengthened, and she has been given a more modern fractional rig, while the owner has been unable to resist demonstrating that he knows a very skilled stainless steel fabricator, as the formerly elegant stemhead has been given an unsightly shiny protective snout, though thankfully that could be disguised by a lick of white paint.

Vintage parade in Sydney Harbour – Wathara (foreground) with (left) an Arthur Robb-designed Lion Class sloop (twice winners of Sydney-Hobart Race), while beyond is one of those Oz flyers which made Rolly Tasker famous.

Vintage parade in Sydney Harbour – Wathara (foreground) with (left) an Arthur Robb-designed Lion Class sloop (twice winners of Sydney-Hobart Race), while beyond is one of those Oz flyers which made Rolly Tasker famous.

Wathara is for sale at Aust $30,000, which is a very modest €19,000, and it suggests she may not be worth bringing back to Ireland. But why bring her to Ireland? After all, these days you’ll find many of the classiest new Irish boats in Croatia. So why not acquire the only DB24 in Australia, and keep her there. For in these WFH days, you can work from anywhere, and avoiding the depths of the Irish winter with two or three months of sailing your own little bit of Dublin Bay in Australia might be just the ticket.

Be warned, however, that it isn’t always sunny. In searching out some images of Wathara, we came across this one of her in a boat-hoist being overseen by the owner, who is sheltering from a Sydney downpour under an umbrella. Is this climate change? It’s certainly the first time we’ve seen a photo of the Australian sailing scene in which an umbrella is actually being used as a shield against rain.

Wathara in the boat-hoist clearly reveals that she’s a Dublin Bay 24. And it is also revealed that – just sometimes - it rains in Oz.

Wathara in the boat-hoist clearly reveals that she’s a Dublin Bay 24. And it is also revealed that – just sometimes - it rains in Oz.

In fairness to the other great Scottish designer who was used by Dublin Bay sailors, it has to be said that the designs of William Fife for DBSC were also re-purposed, although the best-known DBSC re-purposing was the Mylne-designed Zanetta, which was built in Scotland in 1918 and was a DB21 with a simpler rig – she ended her days as a Bermuda-rigged cruising sloop in the Clyde in the 1960s.

But it has only recently been revealed that the lovely Rosemary III, a Fife-designed Bermuda-rigged 9-ton cruiser built by Fife of Fairlie in 1925, is basically the hull of a Dublin Bay 25 with a plank added to the topsides, and the long classic counter finishing with a more clearly-defined and elegantly-curved little transom. She’s lovely. Those Dublin Bay sailors of around 1900, they certainly had an eye for a boat.

The Scottish-built Zanetta of 1918 was a 1902-designed DB21 with a simpler rig

The Scottish-built Zanetta of 1918 was a 1902-designed DB21 with a simpler rig

The classic 1925-vintage 9-ton Fife cruiser Rosemary III is actually the 1898-vintage DB25 design with a plank added, and the counter stern slightly modified in the curved transom.

The classic 1925-vintage 9-ton Fife cruiser Rosemary III is actually the 1898-vintage DB25 design with a plank added, and the counter stern slightly modified in the curved transom.

Ireland’s Contribution to the International Classic Wooden Boat Movement

The traditional and classic wooden boat-building movement is gaining momentum in many parts of the world. It can be part of educational and training schemes which provide skills and purpose in life, usually for young people but also for older folk seeking a new and very absorbing interest. Or it could be to preserve an indigenous boat type whose very survival is at risk. Then again, it may be for the simple pleasure of creating something which produces a tangible result from a satisfying personal project, or a worthwhile community effort. Whatever the reason, Irish sailing’s long history enables it to make a unique contribution to today’s proliferation of classic and traditional newly-built or restored craft emerging from workshops large and small in many parts of the world. W M Nixon looks at some aspects of a fascinating trend.

The half century or so between 1890 and 1945 will be seen by most historians as a period of exceptional global hostility, certainly as measured by the number of wars which were fought during it. So it’s remarkable that an activity like recreational sailing, which needs peaceful conditions to thrive, should have developed so much during that turbulent time.

Admittedly much of the development took place in the “Golden Era” between 1890 and the outbreak of World War I in 1914. But progress was being made in sailing for much of the rest of the period despite the often unfavourable conditions. And for Ireland, that historic time of progress is being reflected today in the number of historic designs for Irish classes which are now first choice for boat-building schools, and other special projects, in many countries including Ireland itself.

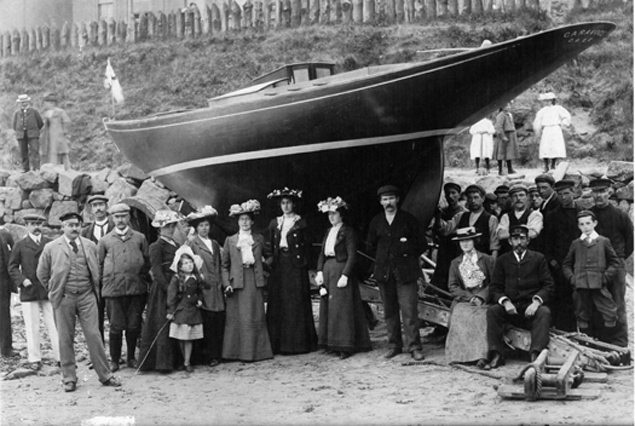

The Alfred Mylne-designed Dublin Bay 21 Garavogue, new-built and ready for launching by James Kelly of Portrush in 1903. Photo courtesy Robin Ruddock

The Alfred Mylne-designed Dublin Bay 21 Garavogue, new-built and ready for launching by James Kelly of Portrush in 1903. Photo courtesy Robin Ruddock

During that half century between 1895 and 1945 when many new local one design classes appeared, Ireland had a pioneering role, as the One Design concept had been first promoted by Thomas “Ben” Middleton’s Water Wags in Dublin Bay in 1887. Thus it was always an innovation which had special resonance in the Irish context, an ideal which it seemed only natural to follow.

Then too, the Royal Alfred YC of Dublin Bay had been promoting the virtues of amateur sailing since 1870 and earlier, so the level playing field provided by One-Designs was a natural follow-on for continuing such enthusiasm. But sustained and long-time support for a particular One-Design type – once it had proved itself satisfactory for the waters on which it sailed – also had much to do with the geography and social structure of Irish sailing.

Put simply, most sailors of the new and growing one design classes in Ireland lived in close proximity to where their boat were based and raced. In contrast elsewhere, thanks to the comprehensive 19th Century railway systems very effectively serving large conurbations such as London and Paris - and to a lesser extent Glasgow and New York - when the weekend was over, many owners and crews headed back to town, sometimes over quite long distances from their boat’s home port.

Garavogue in the final stages of a race when the finishes were still within Dun Laoghaire Harbour. Her owner and crew would have lived within easy reach of the harbour, and the comfortable social bonds within the DB21 class contributed to its long life from 1902 to 1986.

Garavogue in the final stages of a race when the finishes were still within Dun Laoghaire Harbour. Her owner and crew would have lived within easy reach of the harbour, and the comfortable social bonds within the DB21 class contributed to its long life from 1902 to 1986.

But in Ireland, whether it was Cork, Dublin or Belfast, the boat was always nearby, you might meet your fellow sailors quite often during the working week, and evening racing was an important part of the programme. In the greater Dublin area in particular, the cohesive nature of society meant that once a class was popularly established, it thrived so much that some boats from the late 1890s and early 1900s are still in existence and actively racing today.

This means that when a boat-building school seeks a meaningful design which will give added depth to their activities, they know they only have to turn to the wide selection of historic Irish classes to find a boat of suitable size which will have an element of international recognition, it will give those building her an encouraging sense of connection to the past for instructors and trainees alike, and at a practical level, they know there’ll be a diligent class measurer to keep them on track as the job progresses.

A further alternative technical element is added when the no-longer-seaworthy old hull of a revered classic is acquired, and it is then patiently analysed in a process which is a mixture of dissection, re-build and re-creation. Either way, whether building from scratch, or re-creating through various levels of re-building, the learning process is given many useful extra facets.

Water Wags in Dun Laoghaire Harbour. Founded as a class of 13-footers in 1887 and re-born in this larger 14ft 3in version by designer Maimie Doyle in 1900, they have become one of the most popular Irish classic designs for boat-building schools. Photo: W M Nixon

Water Wags in Dun Laoghaire Harbour. Founded as a class of 13-footers in 1887 and re-born in this larger 14ft 3in version by designer Maimie Doyle in 1900, they have become one of the most popular Irish classic designs for boat-building schools. Photo: W M Nixon

And as Irish sailors were not shy in asking designers of international repute to create their new One Designs for them, these re-build or new-build projects may have the added lustre of classic stardom with their undoubted historical significance. Thus in recent years while we may have had new boats being built to the old designs of Irish designers such as Maimie Doyle, Hebert Boyd, John B Kearney and O’Brien Kennedy, equally builders from abroad have been in touch with class associations and other sources in Ireland in order to re-create boats to the designs of William Fife and Alfred Mylne of Scotland, and Morgan Giles of England.

Thus at the moment we have Water Wags being built in Spain and America, Dublin Bay 24s are at various stages of being re-created in Spain, America and France, in France they have also built a Howth 17, another Water Wag and a Shannon One Design, it’s said there’s a Howth 17 being built in the boat-building training school attached to the US Naval Academy in Annapolis, and not surprisingly we hear of enquiries made of Irish class association from those havens of DIY boat-building enterprise, Australia and New Zealand.

Two of the new Howth 17s in their first season in 1898, before sail numbers had been allocated.

Two of the new Howth 17s in their first season in 1898, before sail numbers had been allocated.

The Howth 17 Orla under construction at the Skol ar Mor boat-building school in France, May 2017

The Howth 17 Orla under construction at the Skol ar Mor boat-building school in France, May 2017

In fact, if we look at the range of living or still very well remembered classes in Ireland which have the potential to make designs available for such classics projects, the choice is remarkably comprehensive in size and type. They range through the 14ft IDRA 14s (O’Brien Kennedy, 1946), the 13ft and now 14ft 3ins Water Wags (R A MacAllister 1887 & Maimie Doyle 1900), the Castletownshend Ettes of the 1930s come in at 16ft, at 17ft you have both the Shannon One Designs (Morgan Giles 1922) and the Mermaids (John Kearney 1932), at 18ft we’re already into keelboats and the Belfast Lough Waverleys (John Wylie 1902), move up to 22ft and you have the Linton Hope-designed Fairy Class (1902) on both Belfast Lough and Lough Erne, and there were also the Fife-designed Belfast Lough Class IIIs of 1896, and then at 22ft 6ins there are the Howth 17s by Herbert Boyd (1898).

Up at 25ft there are the Glens (Alfred Mylne, 1945) in Dun Laoghaire Harbour and on Strangford Lough, and also on Strangford Lough at 28ft 6ins there are the Rivers (Alfred Mylne, 1920). Moving towards the 30-31ft mark, we have the Cork Harbour One Designs (William Fife 1896) and the Dublin Bay 21s (Alfred Mylne 1902), and finally above that, with all of them around the 37ft 6ins LOA size, are the Belfast Lough Class I (Fife 1897), the Dublin Bay 25s (Fife 1898) and the Dublin Bay 24s (Mylne, 1938).

Strangford Lough River Class – designed by Alfred Mylne in 1920, they are believed to be the world’s first Bermudan-rigged One Design. Photo: W M Nixon

Strangford Lough River Class – designed by Alfred Mylne in 1920, they are believed to be the world’s first Bermudan-rigged One Design. Photo: W M Nixon

The Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle, an Alfred Mylne design of 1938, was restored in France

The Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle, an Alfred Mylne design of 1938, was restored in France

The attraction of such a good selection is that anyone minded to re-create a classic with a distinguished design and sailing provenance can choose a boat of manageable size from the range available in Ireland. A genuine classic doesn’t have to be a biggie. Keeping it manageable – and in many cases keeping it comfortably trailerable – is the secret of a harmonious project, and the eclectic list of classic projects available for sourcing in Ireland not only offers boats of every size and type up to 40ft, but you can come to Ireland and absorb the atmosphere of the places where the idea of the boat was first conceived, and meet current enthusiasts for sailing the boat which gives a vibrant connection both to the present and the past.

Don’t assume, though, that though it may be happening abroad, there’s nothing going on in Ireland. On the contrary, the possibilities of the Irish classics have been exploited every which way. Serial classics enthusiast Hal Sisk of Dun Laoghaire has instigated so many projects that it’s difficult keeping track, but his CV includes the Peggy Bawn, new Water Wags built in classic style, glassfibre Colleens from an 1897 design, and currently the building of a Dublin Bay 21 from the original ballast keel upwards by Steve Morris of Kilrush, utilising multi-skin construction based on laminated frames.

New life for the 1902-designed DB 21 Naneen in Steve Morris’s workshop in Kilrush. Photo: Steve Morris

New life for the 1902-designed DB 21 Naneen in Steve Morris’s workshop in Kilrush. Photo: Steve Morris

The construction method may be new, but that’s undoubtedly the classic hull of a DB 21 emerging in Kilrush. Photo: Steve Morris

The construction method may be new, but that’s undoubtedly the classic hull of a DB 21 emerging in Kilrush. Photo: Steve Morris

As for Jimmy Furey on the Roscommon shores of Lough Ree, his examples of completely traditional classic style construction of Shannon One Designs and Water Wags – working most recently with Cathy MacAleavey – results in what can only be described as Chippendale work, while down in Ballydehob in West Cork there’s a whole nest of classic restorers, with Rui Ferreira setting quite a pace with new Ettes, a restored Kim Holman Stella, and a much-revived Howth 17.

The Castlehaven Ette Class – Rui Ferreira has been building to this design

The Castlehaven Ette Class – Rui Ferreira has been building to this design

Over on the east coast, when times are hectic in classic boatbuilding, people have found that John Jones over in Anglesey does a very good line in stylish clinker construction, but the venerable Howth 17s – not all of which are operated on large budgets – are currently being kept going by Larry Archer of Malahide, who has a workshop up-country where three of these golden oldies are currently receiving the TLC.

Asgard’s dinghy was re-created in classic style by Larry Archer. Photo: W M Nixon

Asgard’s dinghy was re-created in classic style by Larry Archer. Photo: W M Nixon

Larry is something of a renaissance man in the boat maintenance, repair and building arena, as he is right up to speed with everything to do with glassfibre, yet when Pat Murphy and his group got together to re-create Asgard’s dinghy, it was Larry Archer who delivered the goods, beautifully built in classic clinker style.

As to his present work with the Howth 17s, that is part of a broader project being driven by Ian Malcolm and fellow Seventeen sailors, who may be looking at a class of 23 boats in the foreseeable future. Apart from the new boat built last year in France and the boat reputedly under construction in Annapolis, in a secret workshop on the Hill of Howth, yet another new Howth 17 is quietly under construction to a very high standard.

Such things take time, as the group in Clontarf Y & BC demonstrated when they set out to build a classic timber IDRA 14 for the class’s 70th Anniversary in 2016. They allowed themselves plenty of time, but it was tight enough in the end, yet by the successful conclusion a special bond had been formed among the build team in their Men’s Shed enterprise. It said everything about the deeper benefits of getting involved in a manageable project using time-honoured methods and traditional materials to create something of lasting beauty, value and utility.

The new IDRA 14 ready for launching at the class’s 70th Anniversary Regatta at Clontarf. Photo: W M Nixon

The new IDRA 14 ready for launching at the class’s 70th Anniversary Regatta at Clontarf. Photo: W M Nixon

Cotton Topsails Hoisted as National Yacht Club Welcomes Classic Boat Fleet for Kingstown 200 Cup

It could be over 50 years since a cotton topsail has been seen from the National Yacht Club and this afternoon as the classic fleet arrived "Peggy Bawn", a GL Watson 36–ft Cutter, built in 1894, hoisted her cotton suit of topsail and gaff main.

A temporary pontoon as been anchored off the Carlisle Pier and here the renovated Dublin Bay 24 footer "Periwinkle" this afternoon having sailed from France via the Scilly's and Greystones where some former 24 hands with long association with the class shipped on board, Chris Johnson, David Espey, Chris Craig and Terry Johnson.

On the National Yacht Club platform the Dublin Bay Mermaids were arriving by road and a fleet of "Fifes" from Royal Anglesey Yacht Club were being masted and launched having arrived by ferry.

The fleets arrival for the opening of the Volvo Dun Laoghaire Regatta and the inclusion of the classics for this edition will provide a historic spectacle from the East Pier.

Dun Laoghaire Regatta entries line up at the National yacht club pontoon ahead of tomorrow's regatta

Dun Laoghaire Regatta entries line up at the National yacht club pontoon ahead of tomorrow's regatta

Classic Dublin Bay 24 Yacht to Return to Dun Laoghaire

The last time the Alfred Mylne-designed Dublin Bay 24s raced together in their home waters was Saturday, September 25th 2004 writes W M Nixon. Since then, the class has been through various traumas as projects for a group rebuild/restoration in France fell victim to the financial crisis.

However, the boats were kept in store, and two years ago a complete re-build programme for one of them, Periwinkle, was put into action at Skol ar Mor, the pioneering boat-building school in South Brittany run by Mike Newmeyer.

Sailing aboard the restored Periwinkle. The quality of the bronze fittings on the mast matches the high standard of the restoration. Photo Brian Mathews

Sailing aboard the restored Periwinkle. The quality of the bronze fittings on the mast matches the high standard of the restoration. Photo Brian Mathews

Perwiwinkle has turned all heads any time she goes sailing, but there’s no doubt she’d make most impression in an active class setting. As it is, for this year’s Morbihan Festival of Classic and Traditional Boats in the last full week of May, she’ll be sharing the waters of that noted inland sea with boats from home, as twelve Dublin Bay Water Wags and eight Howth Seventeens are being trailed, ferried, and trailed again to take part in one of the greatest gathering of character boats in the world.

Water Wags in festive mode for their 125th Anniversary in 2012 at Dun Laoghaire Harbour mouth. In ten days time, 12 of them will be in France en route to the Morbihan Festival

Water Wags in festive mode for their 125th Anniversary in 2012 at Dun Laoghaire Harbour mouth. In ten days time, 12 of them will be in France en route to the Morbihan Festival

But while the Water Wags and the Howth Seventeen will be sailing in the enormous fleet, Periwinkle will be on static display afloat, alongside the Skol ar Mor booth at the boat show in the port of Vannes at the head of the Morbihan, though there is a possibility that renowned designer Francois Vivier will take her out for a sail. Happily, though, she’ll soon definitely be sailing – and she’ll be sailing to Dublin Bay.

Owners Chris Craig and David Espey are determined to get her back in time for the Classics Division in the Volvo Dun Laoghaire Regatta from 6th to 9th July, and will be sailing her up from Brittany with a target time of 1st July pencilled-in for arrival in Greystones. Their hope is that former DB24 sailors will then join them to sail on to Dun Laoghaire on Sunday July 2nd.

Class racing act. The Dublin Bay 24s in action at the Dun Laoghaire Woodenboat Regatta 1997. Photo: W M Nixon

Class racing act. The Dublin Bay 24s in action at the Dun Laoghaire Woodenboat Regatta 1997. Photo: W M Nixon

As for the rest of the DB24 fleet, their elegant yet tired hulls are finding new purpose in boat-building schools. In September, Adastra will go to Albaola Scholl in San Sebastian in northern Spain, Zephyra is being shipped across the Atlantic for the Apprentice Shop in Maine, and Arandora is to be completed in Les Atelier de L’Enfer in Douarnenez in Brittany. Mike Newmeyer is working on a plan for Euphanzel, and various proposals are being discussed regarding the future of Harmony and Fenestra.

It has been – and still is - a long and difficult journey. But the arrival of Periwinkle in Dublin Bay will surely be a very significant step

Dublin Bay 24 Wooden Boat–Building Provides Learning Through Working

#woodenboats – You can't make a news item about the wooden Dublin Bay 24 yachts into an add-on to another story. When we focused on October 11th on the challenges of maintaining classic wooden yachts, citing as examples the difficulties being faced with a rusting steel ketch and a 1902-built timber classic, we tail-ended it with an update about the continuing saga of the Dublin Bay 24s, those by now almost-mythical Mylne-designed beauties which have been gone from the bay for nigh on ten years. For our readers, this setting of priorities was a complete reversal of the proper order. They saw the Dublin Bay 24 as outshining everything else. W M Nixon tries to redeem the situation.

We soon learned that the Dublin Bay 24 is the story. Everybody seems to care about them. They were first envisaged in 1934, but didn't finally race as a class off Dun Laoghaire until 1947. They were immediately la crème de la crème. Yet within sixty years, they'd been spirited away to France to form the basis of a class of "accessible classic One Designs" which, after complete restoration, were to be owned or chartered for racing from a new resort on the French Riviera.

The recession put the dampeners on all that for a while, and the boats were reportedly put in store in a warehouse in Southern Brittany. But this past summer, rumours started circulating about one of the DB 24s being restored – effectively rebuilt in fact - to a classic standard which is way beyond the original straightforward and quite economical specification for the class. It turned out that all the rumours were true. And for us here at Afloat.ie, it confirmed that if you just hint at a mention of the Dublin Bay 24s, then people want to know everything.

Periwinkle in Dun Laoghaire in July 1997 for the DB 24 Golden Jubilee Woodenboat Regatta – she is berthed outside sister-ships Harmony and Arandora. Photo: W M Nixon

Periwinkle as she is today, completely re-built except for her ballast keel, and sailing off La Turballe on France's West Coast in September

The "new" boat Periwinkle is based on the keel of the DB24 which never left her birthplace in Scotland, except to visit Dun Laoghaire in 1997 for the class's Golden Jubilee Regatta. But Periwinkle in the late summer of 2014 proved to be an exquisite bit of new work built by an organisation called Skol ar Mor, which is dedicated to preserving, developing and promoting classic boat-building and maritime skills. Naturally people in Ireland wondered why we can't have something similar in Ireland. However, it can be revealed that we do, not least in the form of a remarkable one-man operation in Galway. But first, let's try to unravel the story in France.

On the French Atlantic coast, due east of Belle Ile and midway between the Morbihan and the mouth of the Loire, there's a watery area at Mesquer on the edge of the Briere Nature Reserve. In this place, sea and land intertwine, and a traditional boatyard can have ample space, and easy access to the water, if the people involved are happy to wait for the tide to come up the nearest creek.

Classic boat builders of France. Mike Newmeyer (left) of Skol ar Mor where Periwinkle was re-built, and Cyril Benoist who is restoring Arandora at his own boatyyard in Kercabellec. Photo:Ian Malcolm

A curious confection. The gable wall of Mike Newmeyer's house near the Skol ar Mor boatyard. Photo: Ian Malcolm

It's here that Skol ar Mor has its attractive boat-building shed. Roughly translating as Breton for The School of the Sea, it's a sort of international commune which takes on apprentices for boatbuilding and shipwright's skills. Its President is the noted Francois Vivier, designer of highly individual wooden boats, while the Director is Mike Newmeyer, an energetic American who has taken to life in this region with such exuberance that his house in the midst of it all is an extraordinary confection created from recycled bricks and stonework some of which, in a former life, was part of a mediaeval castle.

Skol ar Mor is constantly on the prowl for interesting boatbuilding challenges which will both inspire and instruct its workforce, with the complete re-build of Periwinkle being one of its most ambitious projects. And as other traditional boatbuilders on both sides of the Atlantic have discovered, the thriving One Design scene in Ireland around the time the 19th Century was turning into the 20th has continued to provide a fertile design sourcebook, for one of the current Skol ar Mor projects is building a classic 14ft Dublin Bay Water Wag.

The new French Water Wag under construction – the stem was supplied by noted Irish classic boatbuilder Jimmy Furey of Leecarrow in Roscommon. Inspecting the work and exchanging ideas are Shannon OD measurer Noel Donagh and Mike Newmeyer of Skol ar Mor. Photo: Ian Malcolm

The word on the grapevine was that the new boat would be making her debut at the Paris Boat Show 2014, which is currently in full swing. But as a technical party from the Water Wag Association discovered when they went down to check out the project at the boatyard and take a few measurements some weeks back, something so boringly bourgeois as precise timekeeping is not really a feature of life in this secret region.

So not only is there no sign of a Water Wag in Paris this week, but there's no sign either of a traditional American Whitehall pulling boat, which was seen beside the Water Wag at a more advanced stage of construction in the hope she really might be ready to go to Paris instead. However, it certainly wasn't a matter of excessive agitation whether she did or not, and the Whitehall has also stayed on in Mesquer to be properly finished.

Planking under way on the carvel built Whitehall pulling boat at Skol ar Mor, which is being built upside, down while the Water Wag (below) is being built upright. Photos: Ian Malcolm

But then, as the Water Wags group of owners Cathy MacAleavy and Ian Malcolm, and advisory measurer Noel Donagh were to discover, the commune of Mesque soon begins to seem like the centre of the universe, while remote places like Paris become no more than incidental fixtures somewhere far inland along the road to the east. But before we go any further, what's this about an "advisory measurer"?

Well, it seems that although they've been in existence since 1903 in their present form, and as a class since 1887, the question of precise measurement in the Water Wags has always been given a fairly generous scope. But the Shannon One Designs, founded in 1922 when much of Ireland was distracted by a small Civil War, have always been interested in precise measurement to the point of obsession. And Noel Donagh, who lives on the shores of Lough Ree, is the Shannon OD Measurer – not a man to be trifled with when you've a classic one-design clinker-built sailing dinghy being built by strange folk in an even stranger part of France.

Noel Donagh and Cathy MacAleavy "discover" the DB24 Arandora undergoing restoration in Cyril Benoist's extensive shed in Kercabellec. Photo: Ian Malcolm

But the strict man from the Shannon One Designs, like the two owners from the Water Wags, found himself being drawn into a state of enchantment. Not only did they make a mutually useful input into construction details of the new boat, but they journeyed to Kercabellac nearby, where Cyril Benoist has his enormous boatshed. There, the main line of business is in looking after fleets of Requins, the popular French One Design keelboats, which look slightly like an International Dragon above water, but like nothing else on sea or land underneath - not even the sharks after which they're named. Yet it wasn't the oddity of the Requins which drew them in, but the fact that in a corner of the shed, the Dublin Bay 24 Arandora is being restored.

Arandora, forsooth. The Golden Yacht or the Banana Boat, depending whose side you're on. Dublin Bay 24 No 8. The youngest of them all by a year or two. Built in Alfred Mylne's own boatyard at Port Bannatyne on the Isle of Bute in 1949. For Col. W. A. C. Saunders-Knox-Gore DSO, Royal Irish Yacht Club and bar. You just couldn't make it up.

In her prime, Arandora was usually sailed by a crew of boisterous young ruffians, most of whom went on to achieve a certain level of respectability, and some even became Pillars of Society. Like everyone else, they were eventually drawn towards the world of more easily-maintained fibreglass boats as the hard-sailed Dublin Bay 24s began to show signs of age. And so, like her sisters, Arandora took the emigrant ship to France.

They're just gorgeous boats. The Dublin Bay 24s at the Golden Jubilee regatta in 1997 are (left to right) Harmony, Arandora and Euphanzel. Photo: W M Nixon

She was showing her age and making a drop of tea. Arandora racing at 1997's regatta, with the bilge pump outlet hose in action over the lee side. Photo: W M Nixon

Just wait till we try to change a light bulb. At the Golden Jubilee regatta, neither Arandora (left) nor Euphanzel were sailing short-handed. Photo: W M Nixon

Only the DB24 Harmony retained the original austere coachroof configuration which now features on the re-built Perinwinkle. Photo: W M Nixon

The Glen Class racing in 1997's Regatta. As the only surviving wooden keelboat class now in Dublin Bay, the Glens in 2014 have upped their game in the quality of their sails. Photo: W M Nixon

The visiting Howth 17s in full flight at the Golden Jubilee Regatta in 1997. The class has increased its numbers since then, while retaining their 1898 rig. Photo: W M Nixon

Party time for the Dublin Bay 24s celebrating their Golden Jubilee at the Royal Irish YC in July 1997 with Perinwinkle from Scotland berthed outside Harmony, and Arandora next the pontoon. Photo: W M Nixon

Only in Ireland would we think that this is a day for the Pimm's. In reality, the many who had sailed on her were taking their farewell from the golden-hulled Arandora at the regatta in 1997. Photo: W M Nixon

A last hurrah. Periwinkle, Harmony, Arandora, Fenestra and Euphanzel berthed together at the RIYC for the unique events of 1997. Photo: W M Nixon

For it had gradually become painfully clear that the Dublin Bay 24 Golden Jubilee Celebrations of July 1997, which expanded to become a major one-off Wooden Boat Regatta involving classics from both sides of Dublin Bay including Water Wags, Mermaids, Glens and Howth Seventeens, were leading inexorably to the last hurrah for the class. Within four years, the new Dun Laoghaire Marina was opened, then the Celtic Tiger was upon us, and ten years or so after their Golden Jubilee, all the 24s – including Perwinkle extracted from Scotland – had been shipped to France in the hope of a better future. People in Dun Laoghaire may indeed have felt a genuine attachment to them, but in the mood of the time their relevance was no longer dominant, while their maintenance costs were prohibitive.

In France with the recession upon the world, they were out of sight and out of mind, yet there were signs of hope. But whereas it was Perwinkle which was the first to re-emerge from the wilderness through a total re-build, Arandora is the first of the truly Dublin Bay boats to begin the long road to recovery, and in her case it will be a restoration rather than a re-build, for although there's much new material going into her, there's quite a bit of the original still in place.

We've struck gold! The tiny area of topside enamel left on the stemhead of the boat undergoing restoration in Kercabellec indicates she is indeed Arandora. Photo: Cathy MacAleavy

Arandora's restoration is verging into re-build territory, but it's reckoned enough of the orginal remains. Photo: Ian Malcolm

And at the very tip of her stem, the timber hasn't been entirely scraped back to the bare wood. There's still a tiny area of that unmistakable and unique hull colour. The golden boat lives on, in a place where classic boat-building skills are revered and central to a way of life. And the work on her restoration will now be monitored, for in May 2015 it's expected that a flotilla of Water Wags and maybe a Howth 17 or three will be trailed to the region to take part in the Morbihan Week for Classics & Traditionals, from Monday May 11th to Sunday May 17th 2015.

Meanwhile, for those who wonder that we don't have such community boatbuilding projects going on in Ireland, the answer is we do, it's just that they have their own special Irish flavour, and you have to seek them out. For instance, you'd be doing well, in driving west along the shores of Galway Bay from Barna into Connemara, to notice Jim Horgan's workshop. For it's a modest little place beside his house right on the road in Furbo, and dealing with the traffic is the priority, rather than finding a very special craftsman going abut his work.

For that's what Jim has been ever since he was signed up to a boatbuilding course at the age of 15 in Youghal. There, his father Joe was the electrician at the hospital, but supplemented his income by running boatbuilding courses in evening classes and on Saturdays. Boatbuilding was so much a part of the family's life that his son Jim was allowed to fabricate his age up to the lower limit of 16 so that he could do one of his father's courses. One way or another, he seems to have had boatbuilding as a steady stream of his life even while he took in moving to Galway in his day job as a teacher, and marrying Mary and setting up home in Furbo.

The cover of Jim Horgan's book on boatbuilding says it all. The Horgan-built boats featured on it in Spiddal harbour, with the white-hulled restored dinghy of Conor O'Brien's Saoirse (left), include in the front row (left to right) a new sister-ship of the Saoirse dinghy, a "sailing currach" known as the Galway Bay 16, a 19ft "Jollyboat Currach", and a 19ft rowing/sailing yawl. Beyond are another 19ft yawl and16ft sailing currach.

His father Joe had a no-nonsense approach to boat-building, and kept a notebook with sketches of his straightforward techniques. It's a path which Jim has followed, while developing it all into a handy little book which is the very soul of modesty, for it doesn't tell you where or when it was published, or indeed where you can get hold of a copy, yet it's a treasure trove of a whole way of looing at life and getting on with the job.

As Jim so neatly puts it, what he teaches is vernacular boatbuilding. Nothing too fancy, just a sensible approach based in real life with a practical timescale which makes satisfactory projects feasible within a manageable period. Sometimes a very manageable period – from his Youghal days, he includes this terse account:

"We built an 18ft salmon yawl with 16ft cedar strips in Youghal Co Cork in just two weeks. It had six solid frames instead of moulds. Clamping strips to these frames made the job very easy, and with lots of help we planked the boat in four days".

Jim Horgan in his workshop in Furbo with the Droleen/Beetlecat nearing completion. Photo: W M Nixon

Jim makes models too. He's here in his workshop with a classic Galway hooker. Photo: W M Nixon

The boatbuilder himself sailing the new Droleen/Beetlecat at Lettermore in Connemara. Photo: Conall Horgan

The diversity of boats he is involved with is bewildering. He restored what is reputedly the dinghy used by Conor O'Brien on Saoirse, and built a sistership while he was still in the mood He has built boats up to 20ft gleoteogs, in fact his main work this winter is repairing a gleoteog he built many years ago. But in his boat-building claases, getting the job done and encouraging people by tangible results within a reasonable time-frame has always been the underlying philosophy.

Thus he states: "My present classes consist of three hours on a weeknight, and four hours on Saturday. Starting in October with templates and moulds to hand, any non-sailing boat should be planked by Christmas, and finished by 1st May".

That's that, then. It's no wonder you'll come across boats of distinctive Horgan origin all around Galway Bay. And he also built three Shannon One Designs for Lough Corrib. His most recent project in his own boatshed was building to the Bray Droleen design (see http://afloat.ie/blogs/sailing-saturday-with-wm-nixon/item/24479-the-irish-heart-is-still-in-wooden-boats). That had emerged from a design created quite a long time ago by O'Brien Kennedy in response to a demand from Bray to re-create the local dinghy class of a hundred years ago. But the boatbuilder of Furbo being Jim Horgan who finds ideas everywhere, the design has further evolved and he readily admits to inspiration from the American catboats, in fact he calls his Droleen – which has been sailing successfully in Connemara regattas – a Beetlecat.

Over the years, Jim Horgan has built up a following among those who have taken much from his boat-building classes, and got afloat as a result. Yet you won't often hear of him away from the shores of Galway Bay, and he is long gone from Youghal, But in his own special way, Jim Horgan is a maritime hero of our time.

Mystery photo. It's Kinvara, and we know that is one of Jim Horgan's Galway Bay 16s in the foreground. But can anyone help us with identifying the mighty Bad Mor with her? Our Galway hooker expert tells us it could be one of three vessels, but he can't be sure which.

What's The Way For Dublin Bay's Classic Boat Sailors?

Last week's Sailing on Saturday blog about the fate of classic yachts was a revelation about our readership. Although three significant historic vessels in three different and distant locations were involved, it was the news about the re-build of the Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle which drew nearly all the attention. Cork Harbour may indeed be the true capital of Irish sailing, but the sheer size and wealth of the South Dublin population accessing the sea through Dun Laoghaire gives it special power and interest. As someone whose home port is outside Dublin Bay, W M Nixon happily returns to the fray.

It's little wonder that Ireland has won more than her fair share of Nobel Prizes for Literature, yet frequently has to look abroad when boats need to be built. We're great at working words into packages of merchandisable literature or high-flown arguments, but we're maybe not so good at building boats, or even looking after them.

But then, Albert Einstein was a keen sailing man, yet despite his intellectual genius, his boat was always a bit of a mess. So maybe it's all of a piece, that last weekend's story about – among other things – the re-build in France of a classic Dublin Bay 24 of 1948 vintage, has in the space of a few days evoked thousands of beautifully-crafted words in the comment section with enough heat generated to warm a small town. (to read comments scroll to the end of last Saturday's blog here – Ed)

Some of the big beasts of Dun Laoghaire's sailing jungle have enthusiastically thrown their hats into the ring, and already we can imagine some shrewd producer of Cable TV docu-dramas setting out a potential cast list for the likes of Roger Bannon and Hal Sisk, while the mysterious Michael Joseph will be played by The Man In The Iron Mask.

The irony of it all is that all these commentators aspire to the same thing – increased vitality and enthusiasm in Dun Laoghaire sailing. And sometimes, if they would take more time to read each other's detailed comments, they'll find they broadly are advocating the same methods of providing boats which will set the local sailing imagination alight, rather than being just another set of plastic fantastics.

But because of the Irish habit of "wanting nothing to do with that other crowd," a lot of creative diplomacy is needed to harness all this energy. Maybe an intense level of debate is unavoidable. For as we've said of another venerable Irish classic boat class which manages to survive and prosper, it does so by inverting the laws of physics, and relying on friction to create energy.

Let's begin with the most straightforward query – Michael Joseph's first question, posted on Wednesday 15th October, as to why do we think that the setup in Dun Laoghaire is not conducive to the preservation and continuing vitality of a class of 38ft classic wooden yachts, in other words the Dublin Bay 24s?

Well, basically it's because Dun Laoghaire has great difficulty in getting some of its acts together. It's physically a very fragmented sort of place. The relationship of the town with the harbour has always been problematical, and it's difficult to generate a general sense of maritime community which might be conducive to encouraging classic yachts which need to be well loved.

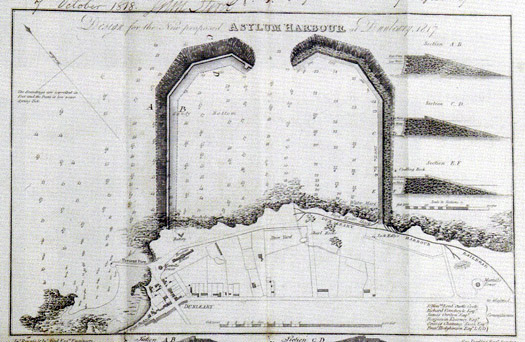

When the plans for the new "Asylum Harbour" were drawn up in 1817, it was seen purely as a shelter facility for shipping caught out in in adverse weather in the Dublin Bay. Although there was a tiny quay at Old Dunleary (the area is still known as The Gut), in the initial plan it was actually shown as being outside the new harbour. The thought that the crews of ships anchored in this new port of refuge might wish to have direct contact with the nearest bit of shore seems if anything to have been actively discouraged.

The proposed pans for an Asylum Harbour in 1817 did not include any suggestions as to possible in-harbour locations for jetties and quaysides, let alone waterfront development, and it actually excluded the small quay at Old Dunleary to the west, though in the final form the West Pier was moved further west to enclose the Old Dunleary pier.

This meant that when the inevitable shoreside facilities began to develop rapidly, it was all on a piecemeal basis. Ideally, when the plan for the harbour was finally agreed, a parcel of property of the same area as the harbour itself should have been secured on the waterfront for the planned development of a complete harbour town. But instead, you got opportunist growth - not really development at all. An unattributed quotation about 19th Century Kingstown, as it had now become, in David Dickson's recently published mighty tome Dublin (Profile Books) tells us much about the official view of the way things had got out of hand in the new seaside town, with speculative developers such as Mr Gresham from the Gresham Hotel putting up terraces of houses every which way:

".....no system whatever has been observed in laying out the town so that it has an irregular, republican air of dirt and independence, no man heeding his neighbour's pleasure, and uncouth structures in absurd situations offending the eye at every turn."

Ouch. For a growing conurbation which prided itself on being called Kingstown, that "republican air of dirt and independence" was a low blow. But as the new railway in 1834 had cut most of the new town off from the sea, an effect which was to become further emphasized by roads running parallel with it, the opportunities for dynamic interaction between town and harbour were restricted. Thus any waterfront space became too valuable to house the workshops of master craftsmen, boatbuilders and shipwrights who might be expected to be readily available to build and maintain local classes of wooden yachts of any significant boat size.

Modern Dun Laoghaire looking northwards, though it should be noted that this photo was taken before the contentious new library was forced into the waterfront between the Royal Marine Hotel and the National Yacht Club. With the water edge's almost exactly marked by the railway and the roads parallel to it, this clearcut division means that, far from the waterfront being part of a shared urban-harbour complex, the complete lack of planning in the early stages has resulted in very little comfortable inter-action between harbour and land, and there is precious little space available for locating specialist small boatyards and marine workshops which would facilitate the continuing good health of substantial wooden classic yachts.

So nowadays, the reality is that basing a cabin sailing yacht of any reasonable size in Dun Laoghaire on a year round basis is too expensive already without the added cost of her being a high-maintenance classic. The best value for money in Dun Laoghaire at the moment is probably provided by a Sigma 33 or a First 31.7 raced as a One Design. Yet in both cases, the necessary membership of one of the waterfront yacht clubs and Dublin Bay Sailing Club, added to the expense of a marina berth and the most basic running costs, means an owner-skipper is shelling out around €10,000 per annum before anything much has been done with the boat.

So although Dublin Bay Sailing Cub works wonders in co-ordinating the racing of hundreds of boats, the survival or otherwise of a class is dictated not by policy decisions on promoting new classes by DBSC, but rather by ruthless market forces, with the sheer expense of sailing from Dun Laoghaire dictating which classes can hang on when times are bad.

The result is that over the years, the surviving classics have become steadily reduced in class numbers, and only the smallest boats survive. With the loss this year of the 17ft Mermaids as an officially recognized Dublin Bay class, as they could no longer guarantee the minimum fleet of five boats, only the 25ft Glens survive from the former serried ranks of several wooden keelboats, and only the 14ft Water Wags survive of the once numerous wooden dinghies.

Yet the growing health of the Water Wags – which can trace their history back to 1887 as the world's first One Design Class - suggests that even in the cut-throat accountancy-led world of Dun Laoghaire Harbour, people still have a natural fondness for classic wooden boats. The current fleet of robust Water Wag dinghies are to a design adopted in 1904, and it adds to their attraction that although they were supposedly designed by local boatbuilder James Doyle, it's generally agreed that the real designer was his talented daughter Maimie.

Mind the gap........ Some of the fleet of a dozen and more classic Waterwags which departed their home waters of Dublin Bay last weekend to race in County Roscommon on the North Shannon's Lough Boderg. Photo: Guy Kilroy

The class have an instinctive sense of their own community, with mutual assistance in maintenance and honing sailing skills a natural part of the healthy mix. One of the factors which has increased their viability is the huge improvement in boat road trailers, for although they remain firmly based in Dun Laoghaire, from time to time you find they've upped and left and gone off for a weekend's racing at some strange and distant location, which might well be described by the management wonks as a bonding exercise

Last weekend, they were having their annual North Shannon Regatta. One of the keenest owners, Guy Kilroy, has a farm in Roscommon on the west shore of Lough Boderg, and the Water Wags descended on him in force. Despite the presence of the great Jimmy Furey building his classic sailing dinghies at Leecarrow on the west shores of Lough Ree, you'd never have thought of Roscommon as a sailing county, but there you go. However, while the coastal Autumn leagues at Crosshaven and Howth saw the seasonal mists soon dispersed, on Boderg in the middle of Ireland it took a long time for the fog to lift. But when it did, the sailing was sublime, and they got in two good races, with four boats level on points, but Ian and Judith Malcolm in the 99-year-old Barbara won on the countback.

Wags-in-a-mist. While the seasonal mists soon cleared at the Autumn Leagues on the coast at Crosshaven and Howth, in the heart of Ireland on Lough Boderg the fog lingered. Photo: Judith Malcolm

Lots of TLC. They may be in the reeds, but the maintenance mustn't be done in a rush.....The high standard of TLC on the Water Wags – the oldest chime in at 110 years – is a wonder to behold. Photo: Ian Malcolm

When all the loving care becomes worthwhile – perfect racing on Lough Boderg last weekend for David McFarland's Moosmie (15) and Vincent Delany's Pansy (3), with Killian Skay's Maureen (29) and Scallywag (44, David Williams and Dan O'Connor) in gentle pursuit. Photo: Guy Kilroy

Maintaining a Water Wag is a very manageable business, but inevitably as the recession recedes, there'll be noises about reviving larger wooden classics, and there's a feeling that the Mermaids aren't completely finished in Dun Laoghaire harbour just yet. There was an interesting twist to this in 2014's Mermaid racing, as the National Championship at Rush was won by Jonathan O'Rourke of Dun Laoghaire's National YC.

Despite being up in Fingal's Rogerstown heartlands where in recent years they've built some supposedly hyper-competitive Mermaids with the clever use of epoxy, Skipper O'Rourke's boat is the 1960 Grieves Brothers built Tiller Girl, which is surely a hopeful sign for the class's future.

The age-defying champion. Mermaid Champion 2014 Jonathan O'Rourke (National YC) with his 1960-built Grieves Brothers boat Tiller Girl. Despite there currently being no racing for Mermaids in Dun Laoghaire, Tiller Girl won the Nationals at Rush even though she was in the area where new supposedly lighter Mermaids, using the exoxy wood system, have recently been built. Photo: W M Nixon

Well, hello Dolly! Named after the world's first cloned sheep, the cloned GRP Mermaid Dolly (white hull) was built in the hope of revitalizing the class, particularly in Dun Laoghaire. But even though she only had a fiberglass hull shell with the rest of her – including the mast – in wood, the new concept was rejected by the class. So Dolly is now based at Sag Harbor in the Hamptons on Long Island in America, where she is much admired, while three of her sisters have proven very to be very durable and effective training boats at a sailing school in West Cork.

Nevertheless, it's at this time of the year that the hassle of maintaining a clinker built wooden boat comes centre stage yet again, and I have to confess that when Roger Bannon produced the fibreglass-hulled Mermaid Dolly, I thought she was a super boat and still do, but the class elders decided otherwise.

Moving on up the size scale, we return to the battleground of the Dublin Bay 21s, still mouldering in a Wicklow farmyard. I only once sailed on one of them under their classic gaff rig complete with jackyard topsail, and despite the enormous spread of cloth, was very impressed by how light and responsive they were on the tiller, but then we were racing in a gentle breeze.

The Dublin Bay 21s await their fate in a Wicklow farmyard

However, this constant refrain about them acquiring dangerous lee helm in strong winds seems to me to be a result of the primitive mainsail arrangement, with the tail of the mainsheet led directly from the counter to cleats on the cockpit coaming. This gave very poor levels of sail control in squalls, and often when the helmsman requested that the mainsheet be quickly but carefully eased to give him better control and keep the boat more upright, it would instead be let go with a run, the mainsail would then be flogging out of control, the close-sheeted headsails would force the bow off, the end of the long mainboom would then hit the water causing the sail to fill with the boat now on a reach, and over and under she'd go.

In a moderate breeze, the Dubin Bay 21s under their original rig undoubtedly carried a small amount of weather helm, and there was no evidence of lee helm at all.

In a moderate breeze, the Dubin Bay 21s under their original rig undoubtedly carried a small amount of weather helm, and there was no evidence of lee helm at all.

Dublin Bay 21 at full cry in the final short in-harbour run from the Coal Harbour buoy to the finish off the club. For this crucial little leg, instant spinnaker setting was essential. It can be noted that the crewmember on the right in the cockpit is trimming the mainsheet by looking aft, the sheet being cleated to the cockpit coaming. In severe weather, this crude method of sheeting could sometimes see the entire sheet being let go completely out of control, whereupon the boat's bow would be forced off by the still-sheeted headsails, the main would then partially fill on the reach as the hyper-long mainboom had started to trail in the sea, and the risk of sinking became very real.

Dublin Bay 21 at full cry in the final short in-harbour run from the Coal Harbour buoy to the finish off the club. For this crucial little leg, instant spinnaker setting was essential. It can be noted that the crewmember on the right in the cockpit is trimming the mainsheet by looking aft, the sheet being cleated to the cockpit coaming. In severe weather, this crude method of sheeting could sometimes see the entire sheet being let go completely out of control, whereupon the boat's bow would be forced off by the still-sheeted headsails, the main would then partially fill on the reach as the hyper-long mainboom had started to trail in the sea, and the risk of sinking became very real.

So it could well be that if a re-built class of Dublin Bay 21s ever emerges, that then they might be given an added safety factor by having the mainsheet led forward, guided close along the underside of the mainboom, and then come down the aft side of the mast to be controlled by a winch on top of the coachroof.

As to whether or not we'll ever see the 21s race again, the odd thing is I think this week's intense exchange here on Afloat.ie may have brought it all a bit nearer. Because if you plough on through the icy politeness of the initial exchanges between Hal Sisk and Roger Bannon, I think you'll discern that they both reckon a cold moulded multi-skin timber hull construction to be a very viable option.

Roger Bannon points out that building a completely new hull on the ballast keel of the original boat is recognized under maritime law as being the continued existence of the same boat, which somehow is an oddly heartening bit of information when you look at the utter dereliction of the DB 21 hulls today.

Could this be the future for the Dublin Bay 21s? Beautiful multi-skin construction under way on Steve Morris's 32ft Harrison Butler designed classic at Moyasta near Kilrush. If it's adopted for the revival of the Dublin Bay 21s, as several of the boats would be buit in one batch construction could be facilitated by the inverted hulls being built on a male mould, thereby making the work easier for newcomer to boatbuilding working on a community basis.

Photo: W M Nixon

And as for Hal Sisk and Fionan de Barra, they've been considering seriously the work being done by Steve Morris near Kilrush in building a cold-moulded classic cutter to Harrison Butler's Khamseen design. Steve was the lead builder in constructing the superb gaff cutter Sally O'Keeffe down in West Clare. So when you see his work on his new boat, all things seem possible, particularly if it's agreed that the new Dublin Bay 21s should be cold-moulded in multi-skin timber on inverted hulls in a maritime community project in Dun Laoghaire, as the basic work would be relatively unskilled, and everyone could have a go at it.

For, as the success of the wonderful CityOne dinghy project in Limerick has shown, in sailing the building of the boat can be as much part of the experience as the subsequent time afloat. But if we ever do see the Dublin Bay 21s sailing again, let it please be with the proper rig. Everyone seems to be pussy-footing around the idea of a more easily handled semi-gunter configuration, maybe with just one jib. What's the point of all that? This isn't meant to be Easy Street. Let's have the full jackyard tops'l and cutter rig and all the bells and whistles, or let's not bother at all.

Should the Dublin Bay 21s be re-built, it has been suggested that for ease of handling and project management they might in future use this simpler "American gaff" rig, as seen here on Zanetta which was built on the Clyde in 1918 to the Dublin Bay 21 design.............

,,,,,but here at Afloat.ie, we reckon that would be the wrong approach. If you're going to have a new Dublin Bay 21, then she should have all the classic bells and whistles and more sail than is good for her, just as we see here with the Ringsend-built Innisfallen having a bit of sport with her spinnaker in the 1950s.

Is The New Dublin Bay 24 The Best Way Forward For Old Classic Yachts?

#classicboat – The preservation of old boats can be a contentious issue, particularly so when the vessel is of significant historical interest at several levels, such as Erskine & Molly Childers' ketch Asgard. Technical and academic question arise as to when a refit become a major refurbishment, when does a preservation become a conservation, or when is a restoration veering into being a re-build? Alternatively, should you simply cut your losses and build from new, but using the original plans if the boat meant something very special to you and the larger maritime community? W M Nixon takes a look at three special boats of Irish interest which are currently at an important changes of course in their voyages through life.

Xanadu is no more. Espanola is seeking a new home. And Periwinkle is born again. And no, we're not launching into some imitation of the rolling cadences of Coleridge's Kubla Khan. On the contrary, we're just considering the current circumstances of three very different boats which have the shared factors of being at a significant juncture in their lives, and having strong links with Ireland.

My own first view of Xanadu was coming round the point at Courtmacsherry about a dozen years ago, and being much taken by a couple of big white raked masts vivid against the green West Cork background – clearly, it was an American ketch. Then close up, her handsome dark blue hull, with a delicately understated clipper bow, confirmed her Transatlantic appearance. And the elegant counter, with its raked and almost elliptical transom, reinforced this conclusion.