Displaying items by tag: Island Nation

Why Shouldn't The Irish Be A Seafaring People?

We may be an island nation, but are we a maritime people in our outlook and way of life? It could be reasonably argued that we most definitely aren’t. On last night’s Seascapes, the maritime programme on RTE Radio 1, Afloat.ie’s W M Nixon put forward a theory as to why this should be so. It’s based on a premise so simple that you’d be very confident somebody else must have pointed it out a long time ago. Yet despite Nixon’s notion being in the realms of the bleeding obvious, even with the aid of Google we cannot find any other commentator or historian making a straightforward suggestion along these lines, but will gladly welcome proof to the contrary.

Why aren’t we Irish one of the world’s great seafaring people? After all, we live on one of the most clearly defined islands on the planet. And it’s an island which is strategically located on international sea trading routes, set in the midst of a potentially fish-rich sea. Our coastline, meanwhile, is well blessed with natural havens, many of which are in turn conveniently connected to our hinterland by fine rivers which, in any truly boat-minded society, would naturally form an integrated national waterborne transport system.

Yet the traditional perception of us is as farmers, cattle traders and horse breeders of world standard, while the more modern view would include our growing expertise in information technology and an undoubted talent for high-powered activity in the international aviation industry. Then too, there is our long-established standing in the world of letters and communication and the media generally. Yet although there are now encouraging signs of a healthier attitude towards seafaring and maritime matters, particularly in the Cork region, for most Irish people the thought of a career in the global seafaring and marine industry simply doesn’t come up for consideration at all.

So why is this the case? I think the basic answer could not be simpler. The fact is, nobody ever walked to Ireland. The prehistoric land-bridges to Britain had disappeared before any human habitation occurred here. Our earliest settlers could only have arrived by primitive boat, and that was only ten thousand or so years ago. But even then, boats were still so basic that the often horrific seafaring experiences would have generated the pious hope of having absolutely nothing further to do with the sea and seafaring for the passengers, once they’d got safely ashore. And that attitude was handed down from one generation to the next.

While the south of England, with its land-bridge still connected to continental Europe, had experienced quite advanced human habitations for maybe as long as 400,000 years, Ireland by contrast was one of the very last places in the temperate zones to be taken over by human settlement, and those first settlers must have come by boat of some sort.

So even in terms of the relatively brief period of human existence on Earth, the settlement of Ireland is only the blink of an eye. Thus in talking of “Old Ireland”, we’re talking nonsense. Ireland is a very new place in terms of its human history. Yet although we’ve only been here ten thousand years, all the archaeological research points to the relatively rapid development of a complex society with some very impressive monuments being built in a relatively short period, and by a society which had become highly organised and technologically advanced within a compact timespan. Newgrange in County Meath - 5000 years old, and eloquent evidence of the sophistication of Ireland of the time

Newgrange in County Meath - 5000 years old, and eloquent evidence of the sophistication of Ireland of the time

Newgrange’s location close to the River Boyne (top right) is a reminder that while basic river transport had become quite highly developed, in this era Irish seafaring was still in its earliest and most primitive stages despite the people’s ability to undertake the advanced calculations used in the construction of Newgrange.

So these were not a people who were just passing through. The earliest Irish were determined to make something special of their new home with some colossal and impressive sacred buildings and structures. To some extent this reflected the possibility that they were totally committed to creating a meaningful life in Ireland perhaps because they saw themselves as now marooned on it.

This sense of being marooned would have become embedded and emphasised in the compact family and tribal groups which very slowly spread across the island as a basic farming and hunting people. The inherited memories of the horror of the voyage to attempt to reach Ireland, in which many lives must have been lost at sea, would have been passed down from generation to generation, and we can be sure that the potential hazards of such an enterprise would lose nothing in the re-telling and embellishment of the ancient stories around the family hearth.

In other words, the longer your people have been in Ireland, then the greater would be your inherited sense of the risk in seafaring. Put another way, you could say that the very earliest Irish were not a seafaring people because the very earliest Irish mammies were absolutely determined that their sons were not going to seek a living on the dreadful sea. In the way of Irish mammies, they made sure that everyone knew this, and they have continued to do so to the present day.

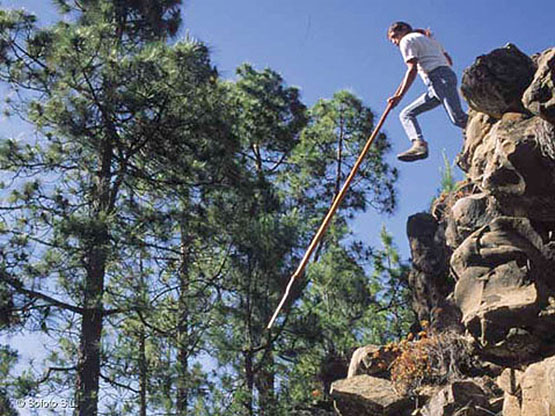

If this emphasis on the adverse effect of inherited unhappy memories seems to over-state the case, consider the circumstances of the ancient people of the Canary Islands. When the Spanish voyagers first discovered the Canaries at a time not so very distant from Columbus’s voyages to America, they thought initially that the islands were uninhabited. It was only later that it was discovered that the highest mountain regions were home to an isolated people who were distantly related to the Berbers of North Africa.

In the remote past, these mountain people’s ancestors had somehow – possibly unintentionally – made the 62 mile voyage across from Africa. It is only eight miles further than the shortest distance between Wales and Ireland. But the seas are significantly warmer, which you’d expect to be a favourable circumstance for encouraging further voyaging. Yet having finally struggled ashore, those first Canary Islanders were very soon distancing themselves from the sea and seafaring.

The Shepherd’s Leap (Salto del Pastor) of the Canary Islands. The earliest islanders in the Canaries turned their backs on boats and the sea so completely that they retreated away from the coasts and went to live in the mountains. There, they developed a unique way of life including this primitive pole-vaulting – now a traditional sport – in order to descend cliffs or traverse ravines

The Shepherd’s Leap (Salto del Pastor) of the Canary Islands. The earliest islanders in the Canaries turned their backs on boats and the sea so completely that they retreated away from the coasts and went to live in the mountains. There, they developed a unique way of life including this primitive pole-vaulting – now a traditional sport – in order to descend cliffs or traverse ravines

Any small enthusiasm they might have had for boats soon disappeared completely, such that they now have no shared knowledge or memory of boats at all. And up in the mountains, their most remarkable talent is the ability to pole vault down into or across the ravines – the Shepherd’s Leap - in order to travel about in their vertiginous homeland, which was seen as preferable in every way to the real dangers of seafaring.

In a Thomas Davis lecture for Seascapes a dozen or so years ago, I discussed the specialised nature of those whose primary interest in the early days of Irish settlement lay in seeing seafaring as a viable way of life. So relatively rare were such people that I reckoned at the time that this talent for exploiting the diverse wealth which the sea offered would provide them with useful survival mechanism for themselves and future generations of their families.

But I now realise that I got it totally wrong. Absolutely the opposite must have been the case. Once you and your people had got safely to Ireland in the first wave of settlers, the seafaring was still so basic and consistently dangerous that having nothing further to do with it was a much better way of ensuring the continuing survival of your genetic stock, whereas producing a family of would-be sailors could see the end of the line in a very short few years.

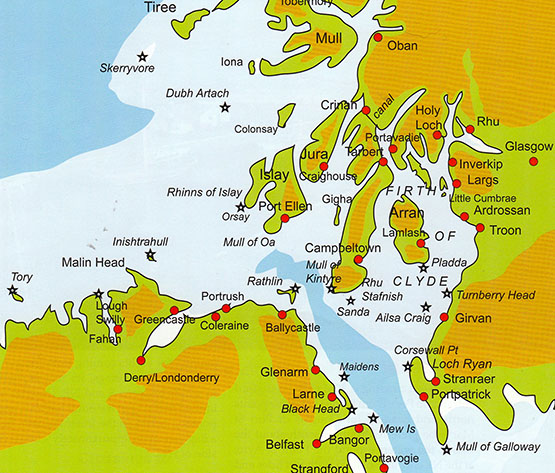

Although the popular view in Ireland is that our earliest ancestors must have sailed direct from Iberia, it seems to me that Western European seafaring would have been so primitive in those days ten thousand years ago that the first settlers must have voyaged across in nondescript vessels from the most easily reached part of the nearby British land, which is the large island of Islay off southwest Scotland.

As it happens, DNA testing on the current population of southwest Scotland indicates that they too have significant elements of our Iberian stock. Thus there is a shared gene pool, and the earliest Irish most likely came by the easiest route from Scotland, whose people in turn had travelled overland from Europe via England.

If that seems a bit hard to take for those of us who like to think that we’re essentially a Mediterranean people left out in the rain, that we’re essentially a formerly seafaring race who came directly by sea from our ancestral homelands in the Basque region, be consoled by the fact that many centuries later Scotland itself was to undergo conquest by invaders from Ireland of the Scoti tribe, who gave a new name to a country formerly dominated by the Picts.

However, that was very much later, when seafaring technology had greatly advanced, and people could regularly sail across the waters between Ireland and Scotland with some confidence. But when the earliest land-starved pioneers were contemplating crossing to Ireland from Scotland, they would have first looked for the shortest route. The absolute shortest distances between Scotland and northeast Ireland is in the North Channel between the Mull of Kintyre and Fair Head in County Antrim. There, the straight line distance is barely a dozen miles, yet you are facing one of the most tide-riven, roughest and coldest sea channels in Europe. And should you make it safely across, the landing at the nearest point on either side is decidedly difficult.

Further south, the shortest distance between the Mull of Galloway in southwest Scotland across the North Channel to northeast County Down is only 20 miles, but here again in early times the landings were inhospitable on either side, and the tides could be ferocious in their adverse impact.

The crossings between Scotland and northeast Ireland which would have been faced by the earliest settlers. While the shortest distance between Kintyre and Fair Head to the east of Ballycastle is just over 12 miles, and the distance between Portpatrick and the nearest part of County Down is barely twenty miles, the entire North Channel between Rathlin Island and the Mull of Galloway is tide-riven, notoriously rough, and with the coldest sea temperatures on the Irish Coast. The earliest voyagers in very primtive boats would thus have had a better chance of a safe crossing, with more options as to their ultimate landfall, by setting off from Port Ellen in Islay, and having avoided the notorious tide race to the southwest of the Mull of Oa, then shaped their course to wherever the winds suited to make a landfall between Inishtrahull and Rathlin. The oldest human settlement in Ireland is at Mount Sandel near Coleraine. Plan courtesy Irish Cruising Club

But if you approached the Scotland-Ireland passage from the mainland of Scotland to the northeast, gradually working your way southwestwards through the southern Hebrides and gaining some seafaring experience with short inter-island hops until you were strategically placed at the natural harbour of what is now Port Ellen on the south shore of Islay, then the prospects were better. You might have still been all of 25 miles from Ireland, but it was a more manageable crossing. You had much greater choice in your possible destinations in making an Irish landfall, as you’d the entire Irish coast from Fair Head to Malin Head to aim for.

In reasonable weather, you could see where you were going, and with prevailing westerly winds there’d be a good chance it would be a relatively easy beam reach if you happened to have a primitive sailing rig, though the likelihood is the early boats were paddled, or rowed in primitive style.

Whatever the method of propulsion, there’s no disputing that one of the oldest sites of human habitation in Ireland is right in the middle of this northern coastline, at Mount Sandel on the River Bann in Coleraine. Yet no matter how much research and archaeology has been undertaken at Mount Sandel and at other ancient sites, no evidence of significant Irish human settlement has been found which goes back any further than ten thousand years.

As it happens, it was ten thousand years ago that mankind first developed the genetic mutation that enabled our ancestors to digest dairy products. But another five thousand years were to elapse before the first cattle were brought to Ireland to find that the place might have been invented for them, and cattle became a source and a measure of wealth. This new socioeconomic development pushed the sea and any form of seafaring even further down the social scale as a viable career option. Who would think of being a fulltime sea fisherman in a land noted as flowing in milk and honey? And even though water transport using rivers became a significant part of Irish life – notably in Fermanagh where the Maguires were to have a water-based mini-Kingdom - the sea was still viewed with suspicion, while the consumption of fish – whether from salt water or fresh – was regarded as socially inferior to eating meat.

Mediaeval map of Ireland. It’s just possible that the island-studded inlet shown on the west coast is the Maguire-ruled Lough Erne, but more likely it is Clew Bay given prominence through Grace O’Malley.

It was only with improvements in seafaring technology and the general seaworthiness of ships that later generations and new groups of settlers might have brought a more positive attitude towards the sea. Then there was a period of about 1200 years – rudely ended by the first arrival of the Vikings around 795AD – when Ireland was remarkably free of invasions, yet enough marine technology had developed in the island for a brief flowering of Irish seafaring with the extraordinary voyaging of the Irish monks.

It has been argued by some scholars that there was no such person as St Brendan the Navigator. But undoubtedly there were great seafaring monks, and those of us who say that if it wasn’t St Brendan then it was somebody else of the same name will occasionally make the pilgrimage across from Dingle to rugged little Brendan Creek close under the west slopes of Mount Brandon on the north shore of the Dingle Peninsula, and wonder again at those Irish men of limitless faith setting out from this sacred spot into the great unknown in light but able boats.

But as it was seaborne asceticism which they sought rather than wealth, it was seen as a highly specialized and rather odd interest when most of the people were much more readily drawn to epic tales of profitable cattle raiding.

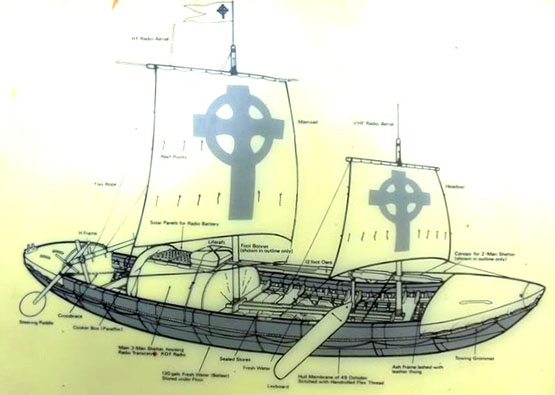

Details of Tim Severin’s oxhide “giant currach” with which – in 1976-77 - he showed that the supposedly mythical Transatlantic voyages of St Brendan the Navigator were technically possible. The St Brendan - which with Denis Doyle’s encouragement was built in Crosshaven Boatyard in 1975-76 – is now on permanent display at Craggaunowen in County Clare.

Then came the Vikings. Say what you like about the Vikings - and everybody has an opinion – but the reality is that their longships represented a quantum leap in naval architecture development. They brought state-of-the-art voyaging in versatile ships way ahead of anything seen before. Yet in time the Vikings were in their turn sucked into the Irish way of doing things, and far from turning Ireland into a seafaring nation, they seem to have literally burned their boats and set up home ashore, gradually absorbing the negative attitude towards the sea of their new neighbours, and taking on board the inevitable anti-seafaring attitudes of their new mothers-in-law

It wasn’t immediately as simple as that, of course. For a while, Ireland was the focal point of the Vikings’ sea trading routes along the coasts of western Europe, while Dublin had the doubtful distinction of being the biggest slave market in the constantly changing Viking western empire, which wasn’t really a territorial empire in the traditional sense, but was more a sphere of active influence and commercial and raiding activity. But it was undoubtedly a major centre which was totally dominated by all Viking activities, including ship-building, and the return to Dublin in 2006 of the 100ft Sea Stallion of Glendalough, a re-creation of one of the biggest Viking ships ever built (in Dublin in 1042), was a telling reminder of just how much Dublin had been to the fore in Viking life, while this video is a timely reminder of the great project completed in Roskilde ten years ago.

Inevitably, people of Viking descent were becoming a significant element in the Irish population, and even today we would naturally expect someone called Doyle to have something of the sea in their veins. Yet the Irish capacity for absorption of newcomers into the old ways of thinking has worked here too. The most common Irish surname today is Murphy. It means sea warrior. While those of us with maritime interests in mind would like to think it referred to an ancient tribe who went forth from Ireland to do successful battle on distant seas, we know in our heart of hearts that the Murphys are descended from warriors – mostly Vikings - who came in from the sea.

In time, they were enticed into domesticity by comely maidens who in due course became the formidable Irish mammies who prohibited any seafaring by their sons. Indeed, so far are most Murphys removed today from the sea that in some parts of the world the name is still a patronising nickname for the potato, something which is useful enough in its way, but its only maritime link is through fish and chips.

After the Vikings and then the Normans – who were really only Vikings with some slightly less rough French manners put on them – subsequent invasions were English-dominated, and the growth of British sea power was done in a manner which made sure that any Irish role in it was strictly of a subservient nature.

Rockfleet Castle in County Mayo, reputed deathplace of Grace O’Malley in June 1603. She was everything she shouldn’t have been, and in heroic style. She was Irish yet a mighty seafarer in command of her own ships, and a woman, yet a ruthless ruler of power and wealth who could combat men on equal terms.

Of course there were local heroes who tried to oppose this, the most renowned being Grace O’Malley, the Sea Queen of Connacht. But even when people of English descent tried to establish a separate Irish seafaring identity, as happened with the merchants of Drogheda, their aspirations would be slapped down by the dominant power and control from the government in London and the influence of the merchants of Bristol.

However, the government only had to look the other way for a moment before there was some local maritime enterprise was trying to flourish, and in the late 18th and early 19th Century the North Dublin smugglers, privateers and pirates of the little port of Rush in Fingal, people like Luke Ryan and James Mathews, were pace-setters in Europe and across the Atlantic, striking deals with Benjamin Franklin among others.

Depending on the state of international hostilities, sometimes their privateering trade could be quite open, and in Dublin the Freeman’s Journal of 23rd February 1779 reported that “we find the little fishing village of Rush has already fitted out four vessels, and one of them is now in Dublin at Rogerson’s Quay, ready to sail, being completely armed and manned, carrying 14 carriage guns and 60 of as brave hands as any in Europe”.

A late 19th century privateer, built for speed. When times were good for privateering, the little port of Rush in Fingal could provide a flotilla of these craft, which at other times could be kept hidden in the Rogerstown Estuary

The Admiral from Mayo. Being press-ganged by the Royal Navy was one of the many career-changing events which resulted in William Brown from Foxford becoming the founder-Admiral of the Argentine Navy.

But the majority of Irish seafarers were employed only in the humblest roles afloat, and often through the activities of the shore-raiding involuntary recruitment drives of the press gangs of Britain’s Royal Navy, However, this could produce some wonderful examples of unexpected consequences. The most complex was William Brown, of Foxford in Mayo, who had somehow risen to be a Captain in the American merchant marine when he was press-ganged into the Royal Navy, and after many vicissitudes, he ended up as a merchant in Buenos Aires. There, thanks to his unexpected acquisition of experience in naval warfare by courtesy of the Royal Navy, he became the founder of the Argentine Navy and an Admiral, as one does…..

Then there was the 18th Century Patrick Lynch of Galway, …….according to some stories, he was press-ganged. Be that as it may, the family made their fortune eventually in South America and a descendant, Patricio Lynch, owned the ship Heroina which played a significant role in Argentine history. The family continued to prosper in many directions, such that one decendant was Che Guevara, while another is the yacht designer German Frers, whose own pet yacht (which he gets little enough opportunity to use, as he is so busy designing boats for others) is called Heriona in honour of the family’s complex historic links through the sea with Ireland.

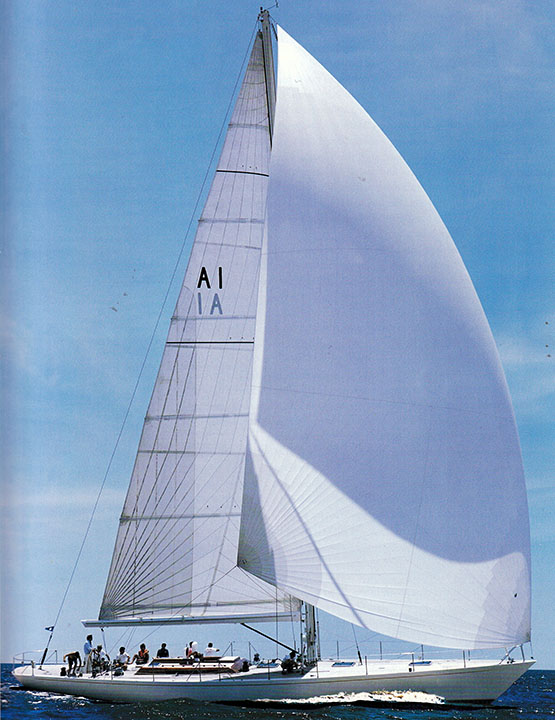

Yacht designer German Frers sailing his personal 74ft sloop Heroina in the River Plate. The boat is named in honour of the historic ship which belonged to his ancestor Patricio Lynch.

But while a very few of the young Irishmen press-ganged by the Royal Navy may ultimately have prospered in unexpected ways, the vast majority most definitely didn’t. Most came to a horrible end, while those who had managed to escape the press gangs’ clutches, together with the rest of the bulk of the native population, were reinforced in their inherited distrust of seafaring in any form.

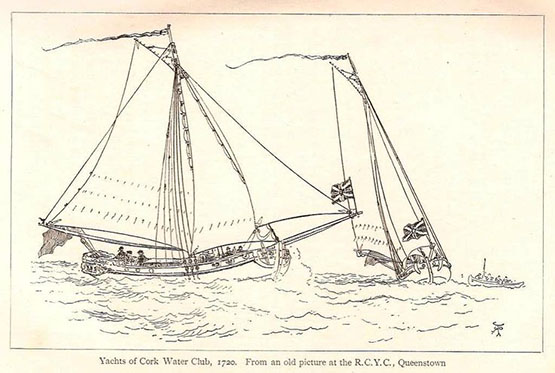

Thus although we may now feel pride in the fact that the world’s first recreational sailing club was established with the Water Club of the Harbour of Cork in 1720, it’s difficult to avoid the conclusion that those great Munster landowners and merchants who founded it were partly doing it subconsciously just to show how very different they were from the ordinary run of Irish people in their attitude to the sea.

First instance of the “have nots” and the “have yachts”? The establishment of the Water Club of the Harbour of Cork in 1720 was a remarkable achievement, but if anything it emphasised the fact that the vast majority of Irish people had no enthusiasm or capability for the sea. Courtesy RCYC.

As for the official attitude when the Irish Free State finally came into being, its was so painfully sea-blind that we still need to draw a veil over its attitude, only noting that the first significant voyage under the new Irish ensign was made by one of that much-maligned class, a yachtsman. This was the great venture round the world south of the capes by Conor O’Brien of Limerick with his little Baltimore-built Saoirse between 1923 and 1925.

Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse departs Dun Laoghaire on her world- girding voyage on 20th June 1923.

O’Brien was to find Ireland so stultifying in its outlook after his return that he sailed away to live elsewhere, and we have to accept that for several decades the official approach reinforced the notion that being interested in the sea is un-Irish. So if we hope to change this attitude which still lingers today, a useful first step is to accept that for many of us, being non-maritime is the most natural thing in the world – we’ve had it instinctively from the very beginning, it’s in our handed-down and repeatedly-instilled inherited memories from the time when our most distant ancestors struggled ashore from battered little boats somewhere on the north coast, knowing that many others had died, and would die, trying to do the same thing.

Far from trying to pretend that this attitude doesn’t really exist, surely a much better way is to accept that it does, but that we’ve researched a perfectly valid explanation as to why this is so. Thus the way forward for Ireland to fulfill her maritime potential is to realize why this attitude is there in us, and take mature steps to offset it.

The fact is, in dealing with the sea, the Irish people have never had a level playing field. We’ve had to live with it and our inherited memories of being on it in very adverse circumstances. Unlike continental land dwellers, we have had no choice in the matter - we don’t see the sea as somewhere excitingly new with endless possibilities, we see it only with inherited distrust. And the determination of the current wave of walking migrants from the Middle East into Europe to attempt the sea crossing at only the narrowest part is further dreadful evidence of this.

But in another area of human endeavour, we’ve shown that we can do the business in competition with other nations. When aviation began to become part of everyday life a hundred years ago, it was unknown territory for all mankind. In terms of getting to grips with flying, it was a level playing field for all.

Yet here we are now in Ireland, an island in the Atlantic which is playing an extraordinarily active and central role in many aspects of aviation management and development, and certainly punching way above our weight. Looking at what we have been able to do in the air, it is surely time to look again at what we might do with the sea if we can look at it from a fresh perspective, and adapt the same can-do energies of the Irish aviation industry to the business of seafaring.

It’s time and more to shake off the old fears of the sea, while always maintaining a healthy respect for its undoubted power. That is best done by being in the vanguard of maritime technological development. And down around Cork Harbour, they’re doing that very thing. It’s just possible that, despite our ingrained anti-maritime attitude, we are beginning to view the sea in a more healthy and positive way. And it’s from our great southern port that we’re beginning to get inspiring leadership as the sea beckons us towards fresh opportunities.

So what, if nobody ever walked to Ireland? So what, if our distant ancestors had a very cold, very wet and very rough time getting here? It’s time to move on. Time to get over it. Time to start seeing the sea in a sensible way.

The little ship that carried the maritime hopes of a new nation. Conor O’Brien’s Saoirse in dry dock, showing the tough little hull that was able to register a good mileage most days in the Southern Ocean while still sailing in comfort. Yet when he returned to Dun Laoghaire in 1925 to complete his voyage with a rapturous homecoming reception, Conor O’Brien was soon to find that beneath the welcome there was increasing official indifference in the new Free State to Ireland’s maritime potential.

Aerial Whale Survey off Kerry Coast, Seagrass at Courtmacsheery

It seems to me that, without dedicated volunteers, there would be a lot of work not done in the marine sphere, so I like when possible, to highlight what dedicated people are doing. Publicity can help them to raise funding they need by drawing public attention to what they ae doing and achieving support. So in the current edition of THIS ISLAND NATION, the Whale and Dolphin Group takes us on an aerial survey over the Kerry coast as they survey whales in Irish waters.

Minke Whale Pictured Off Seven Heads Photo by Oisin Macsweeney

Years ago we would never have thought that whales would be seen off Ireland, but it has happened and this Summer when sailing along the West Cork coastline off the Seven Heads two minke whales came within a few hundred yards of my Sigma 33, Scribbler II. My 11-year-old grandson, Oisin, was quickest to fetch a camera from the saloon and get a picture. The excitement of seeing whales so close was huge for him, his younger brother of 9 years, Rowan, even their experienced seafarer father, Cormac and myself. The sight of whales, which followed on dolphins playing around the boat for a while, was a reminder of how the sea has many aspects and that protecting it and its inhabitants is a responsibility on all of us. Later in the week’s cruise, for which we were blessed with one of the best weeks of the season, the sight of plastic debris floating along and sea grass despoiling the lovely village environs of Courtmacsherry, was another reminder – of how humans are damaging the marine environment.

Also in the programme this week we hear about the plans by Waterways Ireland for the years ahead and the valuable marine reserve asset which Bull Island in Dublin Bay is for the capital city. What is impressive about what is happening there, in my view, is the joint community and public authority efforts to protect it, about which Dublin Council tells us, outlining what combined, joint effort at this level through communities can achieve.

And I hope you’ll get a smile from the tale which Valentia Island native, Dick Robinson, tells us about going to school every day to the mainland, journeying across the bay on the island ferries and how there was learning, not only at school but also aboard and what it taught youngsters about the benefits, believe it or not, of storms hitting the island.

“We were invited into schools in the North Wall and while all the children had grandparents who were dockers, not one of them knew what a docker was, because all of that tradition is gone….”

Amidst the current controversy over where Dublin Port and Dun Laoghaire Harbour will dump what they intend to dredge up in their plans to provide deeper access channels for the larger cruise ships which they both covet and which business they are fighting for, that comment, made to me on the edge of Dublin Bay by a man dedicated to preserving the maritime traditions of the port, should give cause for thought about where all the commercial development has taken the communities which once bounded in Dublin Port and lived from the jobs it provided.

Alan Martin of the Dublin Dock Workers’ Preservation Society was speaking to me, as we sat on the edge of Dublin Bay, for the current edition of my maritime programme, THIS ISLAND NATION. We could hear the sound of seagulls wheeling in the sky, the rumble of noise emanating from the docks, ships passed in and out, as we talked and he had a reality check for me. He told me that 40,000 jobs have gone from the capital’s port since the time when dock labour sustained viable communities.

“Why do the people of Dublin seem to know so little about the place of the docks in the history of Liffeyside and how their role was once the heart-and-soul of Dublin Port, its shipping and its commerce?”

There are many voluntary organisations doing great work in the marine sphere, without whom much of the maritime culture, history and tradition would be lost. The Dublin Port and Dock Workers’ Preservation Society, set up to preserve the history of Dublin Port, is definitely one such. The interview Alan Martin gave me is revealing. They have encountered many obstacles in their self-imposed task.

He surprised me with his revelations about the extent of the maritime-associated jobs that have been lost and the port-side communities which have suffered in the drive towards modernity. He made strong points about how Dublin’s marine traditions can be preserved and turned into a modern, vibrant, beneficial culture for the benefit of the city.

This offers a bridge from the past to the future, effectively a conveyance of pride in past experience to benefit modern life. Other port communities could, with benefit, replicate the commitment of the Dublin Dock Workers’ Preservation Society.

It was an interview I enjoyed doing and I think you will enjoy listening to. I am fortunate to work as a marine journalist and to meet exceptional people in the ports and maritime communities. So it is good to report in this programme, a positive attitude amongst young people in coastal areas, many of whom are joining the lifeboat service. Also featured in this edition of the programme is the delight of a coastal town when it gets a new lifeboat, as I found in Youghal in East Cork.

And there is always something interesting and unusual about the sea to report, such as the 467 million years old sea scorpion found in a river in Iowa in the USA.

Listen to the programme by clicking at the top of the page

Fighting To Clear the Name of Jerome Collins, The World's First Weather Reporter

Every sailor knows the importance of the weather forecast ….

We watch forecasts on television, listen to them on radio, check the Met Eireann forecasts, look at the weather maps in the newspapers… At sea we check the Coast Guard’s coastal radio station forecasts – all part of good, safe, seamanship …

But how many people know that the world’s first weather reporter was an Irishman, from Cork and that, 141 years after his tragic death at the age of 40 in the frozen wastes of Siberia during a failed Arctic exploration, United States Naval records still list him as under arrest at the time of his death. His family descendants allege this is an insulting slur on his memory and, for over a century have fought a battle with the US Government to remove what they say is a ‘stain on his memory.’

It is a battle which the latest member of the family has taken to the Pentagon and found the US Navy didn’t particularly like what was doing when she rang got the phone number of the Secretary of the Navy and rang his office!

Over my years in journalism, unusual stories have been brought to me. This one ranks at the highest level, because Jerome Collins was a man whose Arctic exploration experience puts him close to the life story of the legendary Tom Crean as an explorer. But he is not as well-known and to achieve that is the self-imposed task of his Great, Great Grandniece from Minnesota, Amy Nossum, who I first came into contact with on Emails, then phone calls and finally met when she made her first visit to Ireland during the Summer to see where Jerome Collins is buried, in the old Curraghkippane cemetery, high over Cork City on the northern bank of the River Lee. After his body was found in Siberia, it was brought all the way back to Cork and is regarded as the longest funeral in the world.

The story of Jerome Collins, an engineer born in Cork on October 17, 1841 who supervised the construction of the city’s North Gate Bridge in 1864, is the subject of my AFLOAT Podcast this week, which you can hear here.

Amy Nossum is a determined lady, who tells me how she telephoned the Pentagon and, since she returned home to Minnesota, continues her long-running battle with t the United States Navy.

As I say, an extraordinary maritime story.

Jimmy Tyrrell – An Arklow Maritime Legend

#arklow legend – We are fortunate in this country to have people who are dedicated to the marine sphere and who give freely and willingly of their time and efforts in pursuit of their belief that maritime matters really should matter to the national community.

Jimmy Tyrell from Arklow is such a man. I have known and respected him through his work for the lifeboats for many years.

The RNLI has a proud history of over 190 years and the port of Arklow in County Wicklow, a town founded by the Vikings in the 9th century, lays claim to being the first lifeboat station established in Ireland, back in 1826. Jimmy Tyrrell has led lifeboat operations there for 46 years. His family is legendary in maritime matters.

Twenty-seven years ago Jimmy made a decision. The RNLI named its different classes of boat designs after rivers, but had never used the name of an Irish river. Jimmy was determined to change that and being a determined man, he achieved his goal. So when the new Shannon Class was born, the most modern vessel in the RNLI fleet and the first into Ireland arrived at the Lough Swilly Station at Buncrana in County Donegal, Jimmy was there to see it.

It was a great day for Jimmy, well-deserved and he describes his feeling as he saw the boat arrive on this edition of THIS ISLAND NATION.

When Jimmy retired from RNLI duties in Arklow another member of that great maritime family stood up to take over from him and continue the family association, John Tyrrell, who is now Lifeboat Operations Manager there.

The new Shannon lifeboat at Lough Swilly cost €2.4m and was designed by a Derry man who works for the RNLI at its Poole headquarters. It uses twin waterjets instead of propellers, giving it more manoeuvrability and the ability to operate in shallow waters. The man who designed it is Peter Eyre and he was once saved by the lifeboat service when he got into difficulty on the water, the story of which he tells also on the current edition of THIS ISLAND NATION.

When the RNLI describes a boat as "all-weather..." they mean it, the service always responds to calls for help, even in the worst of sea conditions, so the crews deserve the best boats. The Shannon has a top speed of 25 knots, a range of 250 nautical miles and a unique hull to minimise slamming of the boat in heavy seas, with shock-absorbing seats to protect the crew from impact when powering through the waves. The Lough Swilly lifeboat has been largely funded through a legacy from Derek Jim Bullivant of Bewdley, Worcestershire, in the UK who died in September of 2011.and is named Derek Bullivant. Coxswain, Mark Bennett, commands it and was welcomed by a huge crowd when he and his crew brought the boat from Poole to Buncrana. He tells us how it was an emotional day for him.

BASS BAN

This edition of Ireland's niche maritime programme also has an interesting story about supermarket advertising which can mislead purchasers into thinking they are buying Irish bass when it is illegal to catch them for commercial purposes in Irish waters, where such fishing is banned. So why are the public misled by advertising which says "Irish produced bass" when they come from fish farms abroad?

David Stanton, the Fine Gael TD for Cork East interested – and somewhat pleasantly surprised me – by making an issue of the lack of Government and State attention to the marine sphere. It's not often, I put to him, that a politician is heard to draw attention to maritime matters. He has a good point -that there is no single, central point in the State system, no 'one-stop-shop,' where all maritime enquiries can be dealt with, so anyone proposing a project can be sent from one section of the State services to another so many times they could meet themselves coming back. He is worth listening to and I'll be looking forward to hearing how the self-imposed mission he has declared, to highlight maritime affairs at Government level, gets on.

The island communities join the programme with a regular report, in which we hear why €60,000 a year, not a huge sum of money, is vital to education on the islands.

A lot then, about maritime matters which you can hear THIS ISLAND NATION by clicking on the programme icon above

Your comments are welcome below.

#islandnation – DAH DIT, DAH DIT...The distance which Morse Code could travel was highlighted to me at Valentia Coastal Radio Station when the centenary of its operation was marked writes Tom MacSweeney.

John Draper now in charge of the station recorded for THIS ISLAND NATION the story of Paddy Burke who was on duty watch in Valentia in October of 1942 during World War Two when at 0500 hours he picked up a very weak message in Morse Code, so weak, so faint that he turned off all the machinery making noise in the station at the time in order to hear it and to track it down, which he did. It came from a Second Officer named Smith of the SS GH Jones which had been torpedoed. He was one of 40 crewmen aboard a lifeboat 250 miles South West of the Azores, about 1,250 nautical miles away from Valentia, but Paddy Burke had heard them. He alerted the Royal Navy in London and a destroyer was despatched to rescue them which it did. The Second Officer's hand was so badly injured that it was becoming gangrenous but he had kept sending the message.

Thirty years later a man arrived at the station who introduced himself as the Second Officer who had made that fateful contact with Valentia. Now Capt.Smith he met Paddy Burke who had heard his call for help and they recalled that moment when a Radio Officer on the Kerry island performed his duty to the highest humanitarian and professional standards.

"Paddy is deceased but that story is part of the history of Valentia," John Draper said "and it underlines the professionalism and dedication to duty always shown by the operators at Valentia."

Walking along the corridors of the station and seeing the photographs of rescues they have been involved in and the thanks sent to them by those whom they helped is to realise how vital this station is to safety at sea.

I was pleasantly surprised to receive an invitation to the commemoration as I would have questioned in recent years the attempts by Coast Guard management to close it and Malin Head and to centralise the operations of both stations in Dublin.

You can hear more by listening to THIS ISLAND NATION podcast above.

Your comments are welcome, either below or to: [email protected]

Marine Minister Forecasts Wooden Boat Building Revival

#woodenboat – Marine Minister Simon Coveney is confident that wooden boat building in Ireland is going to be revived writes Tom MacSweeney.

Traditional skills have been lost and there are fears that they will disappear forever, but the Minister sounds a confident note about preserving them on the current edition of my maritime programme, THIS ISLAND NATION.

"This project is going to reinvigorate wooden boat building in Ireland again. It is going to open a new chapter for us," he says. "Hopefully multiple ports around the country will be able to build projects like this in the future. We still have great skill sets of wooden boat building available to us in Ireland which we must not lose. It is projects like this that will keep them alive and encourage a new young generation."

I recorded Mr.Coveney at Liam Hegarty's boatyard at Oldcourt near Skibbereen where the Ilen, the last traditional sailing boat of its kind, is being restored. It is the boat which the legendary Conor O'Brien had built for the Falkland Islanders who so admired his previous vessel, Saoirse, when he sailed it into those islands during his round-the-world voyage in 1923-25. Liam Hegarty's yard at Oldcourt on a bend of the road from Skibbereen to Baltimore in West Cork is one of the few remaining that specialises in wooden boat building.

The Falklanders asked O'Brien, the first Irishman to sail a round-the-world voyage to emulate the boat on which he arrived in Port Stanley. He did as they asked, having the Ilen built in Baltimore, where Saoirse was also constructed. With two Cape Clear Islanders as crew, he sailed it to the Falklands in 1926 where it worked for 70 years until Limerickman, Gary McMahon, had it brought back to Ireland in 1997:

I was the only reporter on the quayside in Dublin when it was landed there from the deck of a cargo ship, looking every bit her age of 71 years at the time. So it was a great feeling to stand on her deck in Liam Hegarty's boatshed where the restoration work has been carried out, in conjunction with the AK Ilen boat building school, initiated by Gary McMahon, the driving force of the project Such a change from the condition in which I had seen her in the Dublin docks 18 years ago.

Gary McMahon, Liam Hegarty and Minister Coveney tell the story on the programme. Gary and Liam are both confident that Ilen will be back in the water, sailing once again. She may provide opportunities for effective sail training. Several sources have provided restoration funding. More is needed for a project which, as the Minister said, can restore Ireland's resource of traditional skills.

Also on the programme you can hear the story of a submarine which sank not once, but twice, which will make you wonder whether superstition about changing the names of boats is correct. And did you know that the Dubs beat the Kingdom ... Not in football, but fishing...?

You can hear more by listening to THIS ISLAND NATION above.

#vor – As the Volvo Ocean Race organisers release the investigation report into the Team Vestas Wind shipwreck in the Indian Ocean, Irish sailor Brian Carlin who was the yacht's Onboard Reporter describes dramatically on the current edition of THIS ISLAND NATION just what happened and how he survived.

"It wasn't what I signed up for in the round-the-world race. We only managed to get 15,000 miles before that night, but it has been character-building. I have learned a lot from it," he says in the interview as he describes how he was hurled forward into a bulkhead :

"I was thrown several metres, banged my head off the forward bulkhead and was stunned. I thought at first that we had hit either a floating container or a whale, but it was a chain of reefs in the Indian Ocean. I got up on deck and saw that we were in serious trouble. It was night time, dark, but there was white water crashing everywhere around the boat and we were lodged on a rock. We stayed six or seven hours on the boat. The Skipper wanted to keep us together which was the right decision, but it was tough going, we were thrown back and forth and the yacht took a heavy battering and it was all in the darkness, the only lights being the personal ones we had. It was a frightening experience to survive and the darkness made it even more so. About half-three in the morning that became too dangerous. There was about six feet to what looked like a safe piece of rock. We deployed the liferafts where we could get some protection for them on the side away from the rocks, but we had to get onto that piece of rock first to be safe. One crew member went across there first, with a rope tied around him and then the rest of us got onto it.

We clung onto that rock until daylight came up and then it was amazing to see that we were in a lagoon area which itself looked beautiful and was in the middle of the ocean."

Were you frightened at any stage that you might not survive, that you could die, I asked him?

"I was. There were two very bad moments. Initially I was a bit shocked. When we were waiting on the boat for daylight, I was afraid that it might overturn on us and we would be trapped. When we were getting off the boat onto the rock I really didn't want to leave it because you were going into the water to try to swim towards rocks which were being battered by waves and it looked like you could be battered too. But that piece of rock was the only place to be safe. The boat was no place to survive. I didn't want to do it, but I had to."

That night in the darkness they did not see sharks, but the following morning when daylight came up, they saw five or six within a hundred metres of the boat.

• Tune into Ireland's niche radio programme above and hear Brian's first-hand account of his experience and the advice he gives to all sailors to take careful notice of the safety recommendations from the RNLI

Also on the programme, the RNLI explains why the organisation is excited about the arrival of the first Shannon Class lifeboat to Lough Swilly and, continuing the explanation of nautical terms for landlubbers, the programme explains why sailors use 'port' and 'starboard' instead of 'left' and 'right'.

Difficult Waters for Irish Sailing, Just 17,000 Registered Leisure Sailors in Ireland

#irishsailing – There are just 17,000 registered leisure sailors in Ireland at present. There has been a decline in sailing, the level of activity has weakened, clubs are losing membership and several marinas have space available for the first time.

The only official participation figure available is for those 17,000 members of clubs registered with the Irish Sailing Association. There are many more sailors who own boats and use them outside of the club structures, so the actual participation levels could be two or three times that number. But there is no doubt about the decline in activity in the sport. The effects of the economic recession, people having less disposable income, loss of jobs, emigration, have all had their effects.

Brian Craig, one of the Directors of the ISA discusses the challenges facing the sport in a frank and direct interview on the current edition of THIS ISLAND NATION, the niche maritime radio programme, which you can hear here. The interview ranges across the still-present perception of the sport as 'elitist' and the methods needed to change this and to increase involvement in the sport.

"There is still a strong core foundation to the sport," Brian Craig says in the interview which discusses the Strategic Plan the Association has drawn up and which has been considered at meetings of ISA members around the country.

Brian Craig

The plan will be put before the ISA annual general meeting in Portlaoise on March 28 for adoption.

GOVERNMENT THINKS THERE IS AN IRISH LANDBRIDGE!

"We are a funny country. We are surrounded by water. We have a Government that thinks there is a landbridge somewhere, but they don't know where it is."

That was the comment of former seafarer Tom O'Mahony when he spoke to the programme at the annual Remembrance Ceremony for those lost at sea in the town of Youghal on the East Cork coastline. It is a coastal town with a great schooner tradition and memories of seafarers who ranged from the River Blackwater onto the world's oceans in various types of vessels. It is also where the programme is compiled, edited, recorded and transmitted every Monday fortnight at 6.30 p.m. and later each fortnight on Near FM in Dublin, Dundalk FM, Dublin South FM and Raidio Corca Baiscinn in County Clare as well as on this website.

Tom O'Mahony said there was a lack of maritime awareness at Government level and recalled the closure of Irish Shipping and the manner in which ships and crews were stranded overseas and men later left without pensions. "And that was company in which seafarers had gone to sea in ships that would not now pass maritime safety requirements."

DISABLED SAILING

The RNLI describes a very courageous disabled sailor on the programme in contrast to the decision of the Paralympics Committee to discard sailing from its programme.

NO PLACE FOR BEING POSH OR A FIGUREHEAD

Also discussed on THIS ISLAND NATION is the use of nautical descriptions in everyday language, such as 'posh,' being a 'figurehead' and 'flogging a dead horse."

#drowning – The Chief Executive of Irish Water Safety, John Leech, shocked me this week when I heard him say at the end of his regular report on my radio programme 'THIS ISLAND NATION':

"I finish on a sad note, that it looks like we have lost ten of our citizens to drowning in the first month of this year, the majority of which appear to be through self-harm."

John, who formerly served with the Irish Navy and is a qualified diver, a tough discipline in which to qualify for underwater work, is also a sailor and a man I have known and respected for many years for his dedicated commitment to water safety. He has driven forward the need to wear lifejackets on boats, for fishermen and other aspects of safety on the water. And his work, leading that of Irish Water Safety, has had an effect. There is now, for example, much more wearing of lifejackets during yacht racing. I have noticed this over recent years and insist upon it on my own boat and, of course, lifejackets should be worn aboard boats of all kinds.

Referring to the drownings during January this year, of which I had not been aware until he revealed the information, John Leech added:

"To help reduce these drownings we need people to complete the HSE Safe Talk of Assist Course, which I have completed myself and recommend highly. Essentially it is a First Aid Course in suicide prevention."

During his report he also said that the Bulgarian Government has made water safety mandatory in their schools, "whilst Ireland has it on the Curriculum, regrettably not enough schools are teaching it."

Among the other facts he revealed:

• Drowning claims the lives of 372,000 people globally each year and is among the ten leading causes of death for children and young people.

• Over half of all drowning deaths are among those aged under 25 years

There are several other surprising facts about drowning and water safety which he discusses in his report which you can hear here.

John Leech IWS CEO

EU RECOGNISES CRUISE SHIP INDUSTRY

"The industry has not got the recognition from the EU which it should, even though it has been around for 25 years," Capt. Michael McCarthy tells me on the programme when he talks about the cruise ship industry and says that recognition appears to, at last, be coming with the scheduling of a conference in Brussels on March 5 and 6.

"This has been sought by all cruise organisations. It will bring together those involved - shipping lines, ports, national and local tourism interests. There is a huge amount of potential in jobs and supplying the industry. Most of the cruise ships which are being constructed and 30 are due in the next four or five years, including mega ships, are being built at four shipyards in Europe. Then there is the tourism sector, ports, logistics, a multi-billion Euro potential, so it is time the EU recognised this," says Capt. McCarthy who is Cork Port's Commercial Manager.

He also speaks about Cork Port's cruise berth facilities at Cobh which are being extended: "To stay at the forefront, we have expanded as the industry has developed."

Capt. McCarthy, Cork Port's Commercial Manager

Work has started on putting in new bollards at the Cobh cruise ship berth at a cost over €1.4m. Cork is the only port in Ireland which can dock the last four generations of cruise ships, any of the new ships built since 2008/2009, any ships over 300-metres cannot berth in any other port in Ireland, he says in the interview which can be heard here.

Why Sea Links Are More Important Than Air Links

#sealinks – In the current debate which has surfaced about the future of Aer Lingus, it is good to hear the realisation in all quarters, from politicians to business, economic and media commentators that Ireland is an 'island nation'. While the importance of air links is being highlighted, those same people could extend their thinking to the maritime links which keep this country alive in a way in which no air linkage can do.

This is emphasised in the leading story in the current edition of my radio programme, THIS ISLAND NATION which you can hear on this website, where I interview the first lady to become President of the Irish Institute of Master Mariners, the professional body for Shipmasters. Sea-going has been a male-dominated profession but Capt. Sinead Reen who lives in Crosshaven, Co.Cork, has done a lot to break that mould. She was also the first woman to qualify as a Deck Officer in Ireland and has served at sea on several types of vessels, including super tankers and cruise ships.

She describes in the interview how she chose a career at sea and, at a time when the Naval Service would not admit women, joined the Merchant Navy: "We are not seen by the general public because we are at sea, carrying the goods, the supplies, the imports, the exports, which this nation needs across the world's seaways. Without ships and seafarers this nation would find it difficult to exist." She discusses life at sea for a woman in a male environment aboardship and speaks of the great opportunities for employment at sea for both women and men. Her election underlines the opportunities of a career at sea for women in what has been a male-dominated profession.

It is an interview worth listening to, as is that about the commemorations planned in the Cork Harbour town of Cobh for the centenary of the sinking of the Lusitania in May.

Hendrik Verway, Chairman of Cobh Tourism, outlines the details of the commemorative plans. Cobh, where survivors of the Lusitania sinking by a German U-boat on May 7, 1915, were landed as well as the bodies of those who were killed in the tragedy, is planning ceremonies on the seafront at Cobh and a sail past by boats on the evening of May 7, with the vessels displaying a single white light to remember those who were killed. Two cruise ships will be in Cobh on the day. One of them, the Cunard's Queen Victoria, will be on a commemorative voyage and on Thursday afternoon, May 7, will sound her ship's whistle at the time at which the torpedo hit the Lusitania, to start a ceremony on the Cobh seafront . A quayside ceremony will start as the whistle sounds and which will conclude at 2.30 p.m., marking the time when the Lusitania sank beneath the waves. 1,198 passengers and crew died. Survivors were landed at Cobh, to where bodies of the dead were also brought and 169 buried. There were 764 survivors. Only 289 bodies were recovered. 169 are buried in the Old Cemetery in Cobh, 149 in three mass graves and 20 in individual plots. Amongst the commemorative events will be a series of lectures and an exhibition of photographs taken in Cobh, then called Queenstown, in the aftermath of the landing there of survivors and bodies by rescue vessels. Many of these photos have not been on public display before and have been digitised for exhibition from original glass plates photographed at the time, through the co-operation of the National Museum. It is also planned to re-enact the funeral of victims to the Old Cemetery in Cobh.

And in another interview on the programme, Paul Bourke of Inland Fisheries Ireland tells me that, for anglers, it has been a good year for the catching of specimen fish.

Fair Sailing...