Displaying items by tag: Harold Cudmore

Harold Cudmore of Cork, Our Main Man in the Global Sailing World

The bundle of energy once known as Hurricane Harold came whirling by Dublin the other day. His daughter was having a pandemic-delayed graduation at Trinity, and Harold Cudmore’s womenfolk had fitted him into a smart suit for the occasion. It could make for a multi-layered episode from the next Sally Rooney novel. But meanwhile, some decompression treatment next day in less formal attire was needed as he wended his way from the city centre en route to the airport and back to Command HQ in the Isle of Wight. A breeze-shooting session over a very leisurely bar lunch in the Portmarnock Hotel ticked all the boxes.

These days, Portmarnock majors on its connections to golf, but somewhere in the midst of the modern much-marbled hotel is the old house of St Marnoch’s, ancestral home of the Jameson family of whiskey fame. Thus it was for a time the home of Willie Jameson, who was the Harold Cudmore of his day, his most notable achievement being as Sailing Master and Owner’s Representative aboard the stellar royal yacht Britannia from 1893 to 1897

Nowadays Willie Jameson tends to be remembered mainly as one of the indecisive afterguard in the unsuccessful America’s Cup challenge with the Watson-designed Shamrock II in 1901, when the owner Lipton recruited too many experts into the sailing management structure. But with Britannia in her glory days, it was just Jameson and the professional skipper John Carter, and the massively authoritative tome Yachts & Yachting, published 1925 under the guidance of sailing guru Brooke Heckstall-Smith, puts Jameson’s abilities firmly in perspective in a review of Britannia’s remarkable early career:

Willie Jameson and John Carter bring the tiller-steered Britannia through the Cowes Week fleet in 1896.

Willie Jameson and John Carter bring the tiller-steered Britannia through the Cowes Week fleet in 1896.

“From 1893 to 1897, Mr William Jameson had charge of her for the Prince of Wales, and the late John Carter was her skipper. It was always said that this combination of talent was remarkable. The amount of hard sea-work done by Mr Jameson, John Carter, and their crew is extraordinary, and especially so when we consider that the weight of spars and running gear in those days was not what it is now, but considerably heavier. In the season of 1896, for instance, the Britannia started in fifty-eight races, and won flags in forty-three; her first race on March 8th and her last on August 15th. She sailed across the Bay of Biscay to the Mediterranean, to the Clyde, to Belfast, to Cork and to the Thames. In her battles with the American yacht Vigilant and with her splendid rival, the Fife cutter Ailsa, I think the success of the yacht was due to the wonderful seamanship of Mr Jameson and John Carter.”

It had all come about because at Cowes Week 1888, John Jameson and his younger brother Willie raced their 88ft cutter Irex boat-for-boat in a near gale of wind from the west with such determination that they won by half a bowsprit length, right in at the castle on the Royal Yacht Squadron line. It was the talk of the waterfront, and as Irex was being given a harbour stow at anchor in Cowes Roads, the royal launch arrived alongside with an invitation for Mr Jameson to join the Prince of Wales for drinks before dinner.

The 1884-vintage Irex – for six years her success was a continuing promotion for the name of John Jameson and his family’s whiskey, and it also introduced his brother Willie to the upper echelons of sailing

The 1884-vintage Irex – for six years her success was a continuing promotion for the name of John Jameson and his family’s whiskey, and it also introduced his brother Willie to the upper echelons of sailing

John Jameson was notoriously shy, and said he’d have to think of a good reason for declining. But whatever Willie was, shy it wasn’t, and he immediately said: “I’m Mr Jameson. I’ll go”. The man who went to drinks stayed to dinner, and when Britannia was built for the Prince of Wales as a near sister to the innovative G L Watson-designed America’s Cup challenger Valkyrie II of Lord Dunraven in 1893, Willie Jameson was the Owner’s Representative from the beginning of the project, and stayed happily involved for the good years from 1893 to 1897.

The point of all this is that when Harold Cudmore took his ease in the conservatory bar in Portmarnock, he should have been sitting under the steering wheel of Britannia. When Britannia was scuttled in 1936 on the death-bed instructions of George V, she was stripped of everything removable, and the Royal Family sent her steering wheel to Willie Jameson as a token of the high esteem in which he’d been held.

But while Willie was as game as the next man for a convivial party, he could be a carnaptious old so-and-so, and he would have shared the sailing community’s distress at the wanton destruction of a still very able and much-loved vessel. So he promptly sent the wheel back saying thanks but no thanks – in his day, he said, Britannia had been tiller-steered.

In discussing this before we got down to wallowing in personal nostalgia, Harold was musing about the ideal setup in the management of racing a big boat, a proper superyacht, which is one of his more significant areas of activity these days. And a very private area it often is too, which means his name isn’t in the headlines as frequently as it was in times past.

“As boat size increases” said he, “the personal importance of the helmsman decreases. For a serious big one, my ideal is to have two others with me in the management and decision process. I’ll reach a consensus with the tactician/navigator and sail setter or whatever you want to call them, and the helmsman will do as we ask. There’s a very wide pool of excellent helmsmen, so I concentrate on getting the other two more tricky positions filled well in advance, but there have been occasions when the helmsman has been recruited the night before – and they’re thrilled skinny”.

Like many of us in his generation, Harold Cudmore never received any formal instruction in sailing. In family-emphasised sailing communities like Cork in the 1940s and ’50s, it was assumed that you picked up sailing skills through a sort of osmosis in Cadet dinghies and International 12s while also crewing for adults in proper yachts. In Harold’s case, it was an accelerated process, as his widowed father Harold Senior with three children – Harold and his siblings Jean and Ron – was to marry again and have another six offspring.

The 33ft Auretta was the summer home in Crosshaven for the young Harold Cudmore and his brother and sister. Designed by James McGruer, she was built in Crosshaven in 1950, and was “Boat of the Show” at a 1951 London Boat Show

The 33ft Auretta was the summer home in Crosshaven for the young Harold Cudmore and his brother and sister. Designed by James McGruer, she was built in Crosshaven in 1950, and was “Boat of the Show” at a 1951 London Boat Show

Thus the house could become very crowded in summer, and Harold Jnr, Ron and Mary spent the summers living and sailing from Crosshaven on the family’s McGruer-designed 1950 Crosshaven-built 33ft sloop Auretta, which became a sort of self-run inshore and offshore sailing academy, functioning so effectively that when Harold became the youngest-ever member of the Irish Cruising Club at the age of 15 in 1959, his proposer was particularly enthusiastic about his abilities as a sea cook.

As the Crosshaven offshore fleet grew with boats being bought in from near and far, Harold was often dispatched as delivery skipper, as it was assumed he knew it all. And he certainly learned from self-taught experience to such good effect that when he was recruited aboard offshore racers, he found that despite being much the youngest, he’d often sailed more deep-sea miles than anyone else on board.

Harold Cudmore and Chris Bruen racing the 505 with which they won the 1969 Irish Nationals, and the Silver Medal at the Worlds in Argentina. Photo: Courtesy RCYC

Harold Cudmore and Chris Bruen racing the 505 with which they won the 1969 Irish Nationals, and the Silver Medal at the Worlds in Argentina. Photo: Courtesy RCYC

But meanwhile, his dinghy racing skills were developing apace, and he was a star in both the Enterprise and particularly the International 505, which was Ireland’s glamour class in those days, with Harold hitting the heights in 1969 with the Irish National title and Silver in the Worlds in Buenos Aires. He’d a formidable talent amounting to sailing genius which clearly needed the largest possible canvas to achieve fulfilment and express itself, but in Ireland in the late 1960s, the concept of professional sailing as we know it now didn’t exist. Paid hands were paid hands and that was it - gentlemen did the racing.

So until the age of 30, he tried to stay the Corinthian course, working in the family’s classically Cork-style retail network. Thus he was overseeing a sort of supermarket in the group when he took the day off to help me race a Swan 36 in the first Cork Week of 1970, when it was part of the Royal Cork Quarter Millenial celebrations.

Most of the fleet in that early Week were sailed by scratch crews left behind after various races from distant parts, for in those days the concept of a semi-inshore week at Cork was only in its infancy, whereas offshore racing was the prestige thing. So Harold’s arrival on board as local expert and tactician was very welcome, but my crew of family and a couple of old mates who smoked to excess found the breezy conditions a bit of a challenge.

Nevertheless, we managed to grab a second with Harold on the tiller giving machine-gun instructions, myself and my future wife and brother doing the best we could with the sheets, and the two old smokers gasping on the foredeck. As we’d done the course so crisply, we finished in early afternoon, so Harold nipped into work and found his manager taking such advantage of the boss’s supposed absence for the day that he fired him in the spot.

He admits himself that his temperament sometimes got the better of him, so naturally he ended up with a certain mutual hostility with the Irish Yachting Association as he tried to put together a Flying Dutchman campaign for the 1972 Olympics at Kiel. Part of the problem was that Harold was so good he found many of the ordinary restraints and procedures irksome, and for many his Flying Dutchman years are best remembered for the fact that one Christmas, many of the Cudmores were spending the holiday at Ardmore in County Waterford, and Harold decided to join them. He roused out his crew and sailed there in the FD from Crosshaven, thirty-plus unaccompanied offshore miles at record speed in the depths of winter…….

The Flying Dutchman – an extremely demanding boat with an enormous genoa, she was one of the first craft in which a skilled crew could achieve planing to windward

The Flying Dutchman – an extremely demanding boat with an enormous genoa, she was one of the first craft in which a skilled crew could achieve planing to windward

1972 had also come up with Cudmore’s winning of the Helmsman’s Championship of Ireland, racing Flying Fifteens on Lough Neagh, but if the unbalanced Olympic campaign of 1972 was recorded as useful experience, in 1973 things took a better turn when Hugh Coveney - until then the owner of the solid Nicholson-designed and built Dalcassian (the former Yeoman XXXIII) – was persuaded to buy the hot Finot-designed alloy-built Half Tonner Alouette de Mer from the Sisk family in Dublin.

Coveney and Cudmore were aiming at serious participation in Cowes Week where their crew would join them, so somehow it ended up with the two of them leaving Crosshaven with time-limited and bad weather brewing. However, the new boat was a joy to sail in the rising west wind, so they let her go as hard as she liked, but approaching the Bishop Rock they got caught up in a breaking wave, and Alouette ended up on her ear and beyond, with the two boyos in the water beside her.

This was all of six years before the Fastnet storm showed that such a situation was no laughing matter, but they thought it hilarious as they grabbed the rail as the boat started to right herself with increasing speed which flipped them back into the cockpit, and on they merrily went, although later a dent was discovered from under the foredeck the where the anchor, normally stowed in the bilges immediately forward of the mast, had been thrown upwards – or more accurately downwards - with sufficient force to leave its mark.

The aluminum-built Alouettte de Mer - after the season of 1973, she had an inexplicable reverse dent in her foredeck……Photo courtesy Hal Sisk

The aluminum-built Alouettte de Mer - after the season of 1973, she had an inexplicable reverse dent in her foredeck……Photo courtesy Hal Sisk

At the time I was writing a weekly sailing column for The Irish Times among eight other regular print outlets, and as the Alouette story had a good ending, I stuck it into the next one and it spread everywhere. In those days Hugh Coveney was still running the big Quantity Surveying company which had been founded by his father, and on his return from Cowes Week, he was summoned to sort some matter in one of their busiest contracts, which was major work on a Convent.

He was ushered into the Mother Superior’s office to find herself surrounded by her special friends, and on the desk The Irish Times of ten days previously. He’d to chat for at least twenty minutes about every detail of this Alouette experience and what it was like to sail with Harold Cudmore before they’d discuss anything to do with quantity surveying.

The boost of featuring in Cowes Week and further developing his international contacts led to Harold Cudmore deciding to go professional in 1974, though at the age of thirty – despite being an extremely youthful and naturally very fit thirty at that – he had to be a young a man in a hurry.

But then 1974 was a year in a hurry down Cork way, for despite the Troubles rumbling in the north and an international oil crisis, the newly-acquired accession to the European Union provided a mood-lifter, and the right people were in place to make the best of it. Johnny and Di McWilliam were developing their new sail loft, and a young designer from New Zealand called Ron Holland had been persuaded to settle in Crosshaven and design a One Tonner for Hugh Coveney.

With the Royal Cork YC now comfortably settled in Crosshaven after the hugely successful celebration of its Quarter Millennium in 1969-70, plus Denis Doyle’s Crosshaven Boatyard firmly on the map through the highly-praised construction in 1970 of the Robert Clark-designed Gypsy Moth V for Francis Chichester - a balm for the lone sailor’s spirits after the soul-destroying experience of Gypsy Moth IV – and with the multi-talented George Bushe and his growing family ready and willing to take on any special boat-building challenge, it was Renaissance time down Cork Harbour way. And Hugh Coveney’s new One Tonner Golden Apple – designed by Ron Holland and exquisitely built by George Bushe and his son Killian – was its flagship.

The charismatic One Tonner Golden Apple of 1974 was one of the first boat to carry a multi-stayed hyper-light Bergstrom-Ridder mast and rigging system.

The charismatic One Tonner Golden Apple of 1974 was one of the first boat to carry a multi-stayed hyper-light Bergstrom-Ridder mast and rigging system.

It’s difficult now to realize just how utterly exciting and new the whole Ton Cup level-rating offshore racing concept was in the 1970s after years in which the world scene had been be-devilled by different rating rules and every boat individually tying to find loopholes which could be exploited to add to the frustration of the fact that it sometimes took hours to calculate just who had won.

With the Ton Cups, first to finish was first, full stop, and the One Tonners at around 36ft LOA made for a very hot class, with their worlds at Torquay in 1974 still remembered as something very special indeed. Golden Apple may not have won, but with the newly-professional Harold Cudmore in full cry, she was undoubtedly the Boat of the Show - one of her competitors at the time was recalling to me the other day her sheer charisma – “She glowed. She seemed to move effortlessly while most of the rest of us struggled. This was history in the making”.

For Harold, the real breakthrough was to come in 1976, when he souped-up one of the standard Holland-designed Half Tonner Shamrock Class being series-built in Cork to produce Silver Shamrock, and took her to the worlds in Trieste with a motley crew including a one-eyed road manager driving a giant Jaguar car as the towing vehicle. And in Trieste, making it up as they went along, they made friends to such warm effect with long distance traditional cruisers Lin and Larry Pardey that at times of personnel crisis in the Cudmore camp, Larry found himself racing as a crewmember on Silver Shamrock.

How else would you celebrate winning the Half Ton Cup 1976 at Trieste? The all-conquering Silver Apple under spinnaker up the Grand Canal in Venice

How else would you celebrate winning the Half Ton Cup 1976 at Trieste? The all-conquering Silver Apple under spinnaker up the Grand Canal in Venice

Whatever about the crewing arrangements, Silver Shamrock won the Worlds, and our man celebrated in typical style by making an overnight passage to Venice and sailing up the Grand Canal under spinnaker. And he also - because he personally preferred to travel light - distributed many of the one-off trophies won among his crew, although ensuring that the perpetual prize was safe. For that’s the Cudmore way: he’s not into silver-cluttered mantelpieces – he moves on.

In fact, with the Half Ton Worlds won in 1976, in subtle ways Harold Cudmore ceased to be a purely Irish sailor, and moved into the global frame. You get a sense of this from a 2019 Vid of reminiscences made by the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia, organisers of the Sydney-Hobart Race

Of course the Cork links remain, they still do in a very deep way, but in sailing they were Cork links with an international context, even if in 1977 – in addition to the Australian Half Ton campaign – it was Cork’s own star boat, the Holland 44 Big Apple RCYC for Hugh Coveney, Clayton Love Jnr and Ray Fielding which provided Harold with a key afterguard role in a successful year.

The Holland 44 Big Apple, Queen of the Fleet in 1977, with Johnny McWilliam on helm and Harold Cudmore to weather of him, keeping an eye on everything. Photo courtesy John McWilliam

The Holland 44 Big Apple, Queen of the Fleet in 1977, with Johnny McWilliam on helm and Harold Cudmore to weather of him, keeping an eye on everything. Photo courtesy John McWilliam

Then in 1979 it was himself and Coveney in dual role as the lead team in the new 43ft Holland-designd Golden Apple of the Sun at the heart of the 1979 Irish Admirals Cup Team. The Irish went into the concluding Fastnet Race leading the series overall, while Golden Apple was leading boat overall at the Fastnet Rock itself, but the Fastnet Storm of 1979 was already remorselessly building, and in it Golden Apple lost her rudder. A rescue helicopter hovering overhead persuaded Hugh Coveney that as owner it was his duty to allow the crew to be taken off as worse weather was predicted, but before Harold was whisked aloft, he left a note on the chart table: “Gone to Lunch”.

Poetry in motion….the Holland-designed 43ft Golden Apple of the Sun in 1979 was leading the Fastnet Race overall at the Rock until the storm struck.

Poetry in motion….the Holland-designed 43ft Golden Apple of the Sun in 1979 was leading the Fastnet Race overall at the Rock until the storm struck.

By 1981 he had linked up with Frank Woods of the National YC to campaign the new One Tonner Justine III, designed by former Ron Holland assistant Tony Castro. However, there was a certain sweet sorrow in their victory in the Worlds, as it was staged in Crosshaven and even though Justine III’s crew included such Cudmore-recruited Cork Harbour regulars as David Gay, Joe English and Killian Bushe, it was unmistakably “National Yacht Club 1981” inscribed on the historic cup. This was doubly ironic, as the One Ton Cup was originally put up for competition in Paris in 1899 by the Earl of Granard, who in 1931 became the Commodore of the National Yacht Club for ten years when steady hands were needed to guide Kingstown yachting into becoming Dun Laoghaire sailing under the new Irish Free State.

Frank Woods’ One Tonner Justine III (National YC, number 290) nosing ahead towards the title in the One Ton Worlds at Cork, 1981. Photo courtesy RCYC

Frank Woods’ One Tonner Justine III (National YC, number 290) nosing ahead towards the title in the One Ton Worlds at Cork, 1981. Photo courtesy RCYC

But for Harold Cudmore, 1981 was a year of increasing global opportunities. Among his many special abilities was a formidable talent for match racing, and his reputation in this led to a call in 1983 to join the Australian camp in Newport, Rhode Island in their bid to wrest the America’s Cup from the New York Yacht Club for the first time. Their Ben Lexcen-designed 12 Metre Australia II, with her innovative wings on the keel, was showing enormous promise, but their helmsman John Bertrand was among the first to admit that his starting techniques were weak when set against the killer instincts of defender Dennis Conner.

In the whole wide world, there was probably nobody better than Harold Cudmore to put fire into the Bertrand belly, and the incredibly intensive coaching sessions they put in, with two 12 Metre boats being worked to death off Newport, certainly did the business with Australia II achieving that extraordinary win.

It also did the business for Harold Cudmore, as he was subsequently involved in consultancy and coaching roles in no less than twelve America’s Cup campaigns with challengers from across the globe. But if he was frustrated in any hopes of leading an actual challenge n the water, he was consoled by becoming the first non-American to win the Congressional Cup in California for match racing in 1985, and in 1991 with the dream team of Gordon Maguire and Joe English aboard the Farr 43 Atara, he notched his first win in the Sydney-Hobart race.

Successful threesome – the Farr 43 Atara provided Harold Cudmore, Joe English and Gordon Maguire with their first Sydney-Hobart win.

Successful threesome – the Farr 43 Atara provided Harold Cudmore, Joe English and Gordon Maguire with their first Sydney-Hobart win.

By this time with increasing maturity, he was completely at ease among crews and owners alike in the big boat scene. His unworried capacity for taking on the literally enormous responsibilities of racing a super-yacht, plus his ability to socialize positively in the après sailing scene where his civilized and wide range of interests outside sailing was an asset, meant that as the years have gone on his top-level sailing has become less visible.

Thus it was others who recorded that after Harold had aided Herbert von Karajan to an elegant and seemingly-effortless yet very complete victory in his notably beautiful Frers Maxi Helisara, the maestro had exulted: “That was even better than conducting the Berlin Philharmonic in top form with Beethoven’s Eroica”.

At this recent Willie Jameson Memorial Lunch in Portmarnock, it was three years since I’d seen Harold, back in pre-pandemic times at the Irish Cruising Club Annual Dinner 2019 in Killarney, when he and Jack Wolfe were both quietly celebrating their sixty years of ICC membership, and a group was quickly formed which between them now have a combined membership of 240 years. We’d a lot to talk about in Portmarnock, and I’m not sure that many lines of thought were completed, so much so that were reminded of the 1970s and ’80, in the great days of the London Boat Show at Earls Court, when it really was the most active global sailing exchange of them all.

They now have a combined Irish Cruising Club membership of 240 years – Dickie Gomes, Harold Cudmore, Jack Wolfe and W M Nixon in Killarney, March 2019. Photo: Alex Blackwell

They now have a combined Irish Cruising Club membership of 240 years – Dickie Gomes, Harold Cudmore, Jack Wolfe and W M Nixon in Killarney, March 2019. Photo: Alex Blackwell

Between intervals of my churning out reams of merchandisable verbiage for various publications, invariably there’d be one night when Harold and I would get together with Malcolm McKeag, formerly of Cultra on Belfast Lough, and at that time a big cheese in the magazine Yachts & Yachting. It all would end in the back of some Earls Court or Kensington restaurant with no easing of the decibel levels, and the three of us wondering at this triumph of hope over experience, for yet again we’d assembled a trio of talkers rather than listeners.

Subsequently, Malcolm went on to become Senior Race Officer at Cowes, and he was in charge when a bunch of London wide boys turned up with their new Laser SB3s to flood the starting line with much the biggest and certainly the worst-behaved OD class ever seen at Cowes Week. He gave them two chances to make a clean start, and when that failed, he ordered the lot of them to wait until the start sequence of all other classes had been completed – it takes for ever, and it certainly softened their cough more than somewhat.

Malcolm is living in stately retirement in Lymington these days, so we’d to give him a call and bring him in on the Portmarnock chat, discovering that has been a slight improvement in 45 years – there was actually some listening going on. But mostly it was inevitably about how the pandemic has made freedom of international movement so difficult if not impossible, particularly for someone like Harold Cudmore.

He continues with enthusiasm unabated as a sailing citizen of the world, even if he admitted with some sadness that his long experience of racing at the very sharpest end has somewhat blunted his enthusiasm for homely local racing in Cowes. This is despite being a long-standing member of the Royal Yacht Squadron, notwithstanding his initial reaction to the membership invitation with a horrified: “But I’m far too young!”

“Here’s one for Crosser!” Harold Cudmore holds the trophy aloft after the Cork Harbour OD Jap won overall in the classics at St Tropez in September 2021. RCYC Admiral Colin Morehead on left.

“Here’s one for Crosser!” Harold Cudmore holds the trophy aloft after the Cork Harbour OD Jap won overall in the classics at St Tropez in September 2021. RCYC Admiral Colin Morehead on left.

Yet he retains his faithful love for the Royal Cork, and one of his sadnesses from the pandemic is that, even if the club kept up its spirits with admirable camaraderie, the shut-down effectively obliterated the Tricentenary Celebrations.

“If we’d got that going well with a bit of luck with the weather, the momentum might have carried us on to a more realistic bid to host the America’s Cup. People would have come to appreciate what Cork Harbour can do, but equally it would have given everyone an idea of just how much needs to be done to make for a realistic bid”.

The Irish weather is the great unknowable, and my own feeling is that the AC idea is beyond serious contemplation unless the entire island can be towed at least 450 miles southwards. But it’s a tricky subject, so on our way to the airport we talked of what Harold might have been doing had there not been a pandemic.

Winter sport….Harold Cudmore helming the classic Sydney Harbour 18-foter Yendys.

Winter sport….Harold Cudmore helming the classic Sydney Harbour 18-foter Yendys.

“The way it has spread globally might have been precisely designed to screw up my regular annual programme. I usually spend the three winter months in Australia on a mixture of work and fun – I love the classic Sydney Harbour 18s, so that covers both categories. Then it’s back to Europe for a little while and then it’s off to the Caribbean for the racing season there before returning for the classics, mostly in the Mediterranean”

He gets particular enjoyment out of coaxing an exquisitely finished big classic gaff rigged yacht to give of her best, and there’s a telling photo of him tensed up aboard the 19 Metre Mariquita, racing in zephyrs of the Mediterranean. I tell him it looks as though he’s physically willing the boat from one puff of wind to the next.

Willing the boat onwards with sheer physical tension – focused body language from Harold Cudmore aboard the 19 Metre Mariquita, hopping successfully from zephyr to zephyr in the Mediterranean

Willing the boat onwards with sheer physical tension – focused body language from Harold Cudmore aboard the 19 Metre Mariquita, hopping successfully from zephyr to zephyr in the Mediterranean

“It worked”, says he. “We were first, and we beat the enormous 23 Metre Cambria boat-for-boat”.

And despite life’s restrictions, it gave him special pleasure to take the Royal Cork’s Fife-designed restored Cork Harbour OD Jap to Les Voiles de St Tropez at the end of September. Something very special was extracted from the season, with Jap taking the overall win. And then, the Main Man was gone, gone back to the Isle of Wight. But back home, the next time I opened the in-box, there was news of the original Golden Apple, in lovely order in Denmark even though no-one had heard a word of her for at least thirty years, and we’d talked of her in the past tense in St Marnoch’s.

So the news was immediately emailed to Cudmore HQ in Cowes with only one comment:

“Spooky or what?”

He was up for it.

“Bizarre”.

She is alive and very well – Golden Apple is in good shape in Denmark, just two years short of her Golden Jubilee. Photo courtesy RCYC

She is alive and very well – Golden Apple is in good shape in Denmark, just two years short of her Golden Jubilee. Photo courtesy RCYC

Harold Cudmore & The Admiral's Cup, RORC Video Interview

Royal Cork yachtsman Harold Cudmore, Ireland spoke with Louay Habib for an hour-long show focusing on the Admiral's Cup for the 11th edition of the RORC Time Over Distance Series.

In the 1970s Cudmore was one of the first sailors to travel the world to compete at international yachting events, especially match racing. In 1986 he became the first non-American to win the Congressional Cup. In the America's Cup Cudmore was heavily involved in several British campaigns during the 1980s. He was also head coach of the 1992 winning campaign America3 and coach for the all-women's campaign in 1995.

Between 1977 and 1993 Cudmore took part in seven editions of the Admiral's Cup - Racing for Ireland, Great Britain, Australia and Germany. In 1989 he was the mastermind ashore for the victorious British team. To this day, Harold Cudmore travels the world, racing in a wide variety of inshore and offshore events. His amazing abilities as a yachtsman are only matched by his talent for storytelling!

At the height of their fame, the unrestricted Sydney Harbour 18-footers worked on the theory that the more sail you could carry, then the faster you’d go writes W M Nixon. With serious betting going on among spectator crowds following the racing on the Harbour’s ferries, there was a lot at stake. And even if they had to keep adding extra crew-weight in order to handle and counter-balance the huge and increasing press of cloth, for years the accepted wisdom was pile them high, pile them on, and pile drive down the Harbour.

As for the hazards of capsizing or simply sailing under with the ludicrous load of sailpower, well, the water was warm - and if there were any sharks about, the huge white spread of cloth would of course frighten them away…...

Sailing on the edge under a very big mainsail – Harold Cudmore on the helm aboard Yendys

Sailing on the edge under a very big mainsail – Harold Cudmore on the helm aboard Yendys Yendys making many knots and lots of fuss downwind

Yendys making many knots and lots of fuss downwind

Maybe so. But inevitably somebody got to thinking that a cleverer more modern rig - with less weight of crew needed to handle it if the crew was well outboard trapezing on a ramp - might produce a better result. The outcome of this thinking was a race-winner whose descendants included the Olympic 49er. The new 18ft skiff may not have looked so madly exciting, and there were certainly fewer prangs for the spectators to enjoy, but the more modern boats were on the money, and that was what really mattered.

"Pile them high, pile them on, and pile drive down the Harbour"

The old boats disappeared with astonishing rapidity until one of the greatest of them, the 1925-built Yendys, was spotted being used as a utterly nondescript little motorboat whose main purpose in life was a spot of fishing. But miraculously she was saved and restored to her former crazy glory, as were others of the class’s vintage days, and occasionally they’re allowed afloat for some racing, while Yendys in particular is saved for sailing treats for special guests.

Getting settled in. The spinnaker is up and the boy from Cork is at the helm enjoying the sail

Getting settled in. The spinnaker is up and the boy from Cork is at the helm enjoying the sail

Ireland’s own veteran sailing superstar Harold Cudmore of Cork fitted the role to perfection during his current holiday in Australia with wife Lauren (she’s from Malahide), and as Bruce Kerridge’s photos show, the boy did well and it seems that for once the good old Yendys didn’t end up on the beach needing reassembly after a capsize, something which – to say the least - is not unknown.

Meanwhile, Harold fitted in a visit to the Woodenboat Show in Hobart, Tasmania and a 50-knot jaunt on Peter Cavil’s replica 1922 powerboat which - like Yendys – certainly looks the business. He also linked up with designer Ron Holland enjoying the Australian summer, and doubtless also touched base with renowned former Crosshaven sailmaker and current international gliding ace Johnny McWilliam, who recently celebrated a certain extremely significant birthday with a zero at the end of it in Australia with sons Tom and Jamie.

Now that really is speed – Peter Cavil’s 1922-replica Marguerite has been notching speeds north of 50 knots

Now that really is speed – Peter Cavil’s 1922-replica Marguerite has been notching speeds north of 50 knots

This weekend’s two-day All-Ireland Sailing Championship at the National Yacht Club in Dun Laoghaire, racing boats of the ISA J/80 SailFleet flotilla, is an easy target for facile criticism. Perhaps because it tries to do so much in the space of only two days racing, with just one type of boat and an entry of 15 class championship-winning helms, inevitably this means it will be seen by some as falling short of its high aspiration of providing a true Champion of Champions.

Yet it seldom fails to produce an absolute cracker of a final. Last year, current defending champion Anthony O’Leary of Cork, racing the J/80s in Howth and representing both ICRA Class 0 and the 1720 Sportsboats, snatched a last gasp win from 2013 title-holder Ben Duncan of the SB20s, thereby rounding out an utterly exceptional personal season for O’Leary which saw him go on to be very deservedly declared the Afloat.ie “Sailor of the Year” 2014.

So this year, with a host of younger challengers drawn from a remarkable variety of sailing backgrounds, the ever-youthful Anthony O’Leary might well see himself in the position of the Senior Stag defending his territory against half a dozen young bucks who will seem to attack him from several directions. And with winds forecast to increase in strength as the weekend progresses, differing talents and varying levels of athletic ability will hope to experience their preferred conditions at some stage, thereby getting that extra bit of confidence to bring success within their reach. It’s a fascinating scenario, and W M Nixon tries to set this unique event in perspective.

When the founding fathers of modern dinghy racing in Ireland set up the Irish Dinghy Racing Association (now the ISA) in 1946, they would have been reasonably confident that the immediate success of their new pillar event, the Helmsman’s Championship of Ireland, gave hope that a contest of this stature would still be healthily in being, and still run on a keenly-followed annual basis, nearly seventy years later.

They might even have been able to envisage that it would have been re-named the All-Ireland Championship, even if their original title of Helmsman’s Championship had a totally unique and clearly recognisable quality, for they’d have accepted its fairly harmless gender bias was going to create increasing friction with the Politically Correct brigade.

The Stag at Bay? Anthony O’leary sniffs the breeze last weekend, in charge of racing in the CH Marine Autumn league. This weekend he defends his All-Ireland title in Dun Laoghaire. Photo: Robert Bateman

The Stag at Bay? Anthony O’leary sniffs the breeze last weekend, in charge of racing in the CH Marine Autumn league. This weekend he defends his All-Ireland title in Dun Laoghaire. Photo: Robert Bateman

Sailing should be fun, and run with courtesy – invitation to enjoyable racing, as displayed last weekend in Cork on Anthony O’Leary’s Committee Boat. Photo: Robert Bateman

Sailing should be fun, and run with courtesy – invitation to enjoyable racing, as displayed last weekend in Cork on Anthony O’Leary’s Committee Boat. Photo: Robert Bateman

But what those pioneering performance dinghy racers in 1946 can scarcely have imagined was that, 69 years later, no less than a quarter of the coveted places in the All-Ireland Championship lineup of 16 sailing stars would be going to helms who have qualified through winning their classes within the Annual National Championship of a thirteen-year-old all-Ireland body known as the Irish Cruiser-Racing Association.

And if you then further informed those great men and women of 1946 that those titles were all won in an absolute humdinger of a four-day big-fleet national championship staged in the thriving sailing centre and Irish gourmet capital of Kinsale, they’d have doubted your sanity. For in the late 1940s, Kinsale had slipped almost totally under the national sailing radar, while the town generally was showing such signs of terminal decline that there was little enough in the way of resources to put any food on any table, let alone think in terms of destination restaurants.

So in tracing the history of this uniquely Irish championship (for it long pre-dates the Endeavour Trophy in England), we have a convenient structure to hold together a manageable narrative of the story of Irish sailboat racing since the end of World War II. Add in the listings of the Irish Cruising Club trophies since the first one was instituted in 1931, then cross-reference this info with such records as the winners of the Round Ireland race and the Dun Laoghaire to Dingle Race, beef it all up with the winners of the national championship of the largest dinghy and inshore keelboat classes, and a comprehensible narrative of our national sailing history emerges.

The veteran X332 Equinox (Ross McDonald) continues to be a force in Irish cruiser-racing, and by winning her class in the ICRA Nationals in Kinsale at the end of June, Equinox is represented in the All Irelands this weekend by helmsman Simon Rattigan. Photo: W M Nixon

The veteran X332 Equinox (Ross McDonald) continues to be a force in Irish cruiser-racing, and by winning her class in the ICRA Nationals in Kinsale at the end of June, Equinox is represented in the All Irelands this weekend by helmsman Simon Rattigan. Photo: W M Nixon

It’s far from perfect, but it’s a defining picture nevertheless, even if it lacks the inside story of the clubs. Be that as it may, in looking at it properly, we get a greater realization that the All-Ireland Helmsman’s Championship (or whatever you’re having yourself) is something very important, something to be cherished and nurtured from year to year.

Of course I’m not suggesting that we should all be out in Dublin Bay today and tomorrow on spectator boats, avidly watching every twist and turn as eight identical boats race their hearts out with a variety of helms calling the shots. Unless you’re in a particular helmsperson’s fan club, it’s really rather boring to watch from end to end, or at least until the conclusion of each stage and then the final races.

This is very much a sport for the “edited highlights”. The reality is that no matter how they try to jazz it up, sailing is primarily of interest only to those actively taking part, or directly engaged in staging each event. When great efforts are made to make it exciting for casual spectators, it costs several mints and results in rich people and highly-resourced teams engaged in costly and often unseemly battles to which genuine sporting sailors cannot really relate at all.

But with its exclusion of Olympic and some High Performance squad members, the All-Ireland in its current form is the quintessence of Irish local and national sailing. It’s almost compulsive for its participants, it provides an extra interest for their supportive clubmates, and in its pleasantly low key way it’s a genuine expression of real Irish sailing, the sailing of L’Irlande profonde.

So of course we agree that it might be more interesting for the bright young people if it was raced in something more trendy like the RS400s if they could find sufficient owners to risk their boats in this particular bear pit. And yes indeed, the ISA Discussion Paper and Helmsmans Guidelines of 2012 did indeed hope that within three years, the All Ireland would be staged in dinghies.

But we have to live in the real world. Sailing really is a sport for life, and some of our best sailors are truly seniors who would be disadvantaged if it was raced in a boat making too many demands on sheer athleticism, for which the unattainable Olympic Finn would be the only true answer.

But in any case, if you watch J/80s racing in a breeze, there’s no doubting the advantage a bit of athletic ability confers, yet the cunning seniors can overcome their lack of suppleness and agility with sheer sailing genius.

While they may be keelboats, in a breeze the J/80s will sail better with some athleticism, as displayed here by Ben Duncan (second left) as he sweeps toward the finish and victory in the 2013 All Irelands at Howth. Photo: Aidan Tarbett

While they may be keelboats, in a breeze the J/80s will sail better with some athleticism, as displayed here by Ben Duncan (second left) as he sweeps toward the finish and victory in the 2013 All Irelands at Howth. Photo: Aidan Tarbett

Yet a spot of sailing genius can offset the adverse effects of advancing years – Anthony O’Leary (right) with Dylan Gannon (left) and Dan O’Grady after snatching victory at the last minute in 2014. Photo: Jonathan Wormald.

Yet a spot of sailing genius can offset the adverse effects of advancing years – Anthony O’Leary (right) with Dylan Gannon (left) and Dan O’Grady after snatching victory at the last minute in 2014. Photo: Jonathan Wormald.

But another reality we have to accept is that Ireland is only just crawling out of the Great Recession. And in that recession, it was the enduring competitiveness of ageing cruiser-racers and the sporting attitude of their owners which kept the national sailing show on the road. Your dyed-in-the-wool dinghy sailor may sneer at the constrictions of seaborn truck-racing. But young sailors who were realists very quickly grasped that if they wanted to get regular sailing with good competition as the Irish economy went into free fall, then they had to hone their skills in making boats with lids, crewed by tough old birds most emphatically not in the first flush of youth, sail very well indeed.

Thus in providing a way for impecunious young people to keep sailing through the recession, ICRA performs a great service for Irish sailing. And the productive interaction between young and old in the ICRA fleets, further enlivened by their different sailing backgrounds, has resulted in a vibrant new type of sailing community where it is regarded as healthily normal to be able to move between dinghies and keelboats and back again.

The final lineup of entries is a remarkable overview of the current Irish racing scene, and if you wonder why the winner of the GP14 British Opens 2015, Shane McCarthy of Greystones, is not representing the GP 14s, the word is he’s unavailable, so his place is taken by Niall Henry of Sligo.

2014 Champion Anthony O'Leary, RCYC

RS400 Alex Barry, Monkstown Bay SC

GP14 Niall Henry ,Sligo Yacht Club

Shannon OD Frank Browne, Lough Ree YC

Flying Fifteen David Gorman, National YC

Squib Fergus O'Kelly, Howth YC

ICRA 1 Roy Darrer, Waterford Sailing Club

Mermaid Patrick, Dillon Rush SC

Laser Std Ronan Cull, Howth YC

SB20 Michael O'Connor, Royal St.George YC

IDRA14 Alan Henry, Sutton DC

RS200 Frank O'Rourke, Greystones SC

ICRA 2 Simon Rattigan, Howth YC

ICRA 4 Cillian Dickson, Howth YC

Ruffian Chris Helme, Royal St.George YC

As a three-person boat with a semi-sportsboat performance, the J/80 is a reasonable compromise between dinghies and keelboats, and the class has the reputation of being fun to sail, which is exactly what’s needed here.

The Sailing Olympics and the ISAF Worlds may be terribly important events for sailing in the international context, but nobody would claim they’re fun events. Equally, though, you wouldn’t dream of suggesting the All-Ireland is no more than a fun event. But it strikes that neat balance between tough sport and sailing enjoyment to make it quite a good expression of the true Irish amateur sailing scene.

Inevitably from time to time it produces a champion whose sailing abilities are so exceptional that it would amount to a betrayal of their personal potential for them not to go professional in some way or other. But fortunately sailing is such a diverse world that two of the outstanding winners of the Helmsman’s Championships of Ireland have managed to make their fulfilled careers as top level professional sailors without losing that magic sense of fun and enjoyment, even though in both cases it has involved leaving Ireland.

Their wins were gained in the classic early Irish Yachting Association scenario of a one design class which functioned on a local basis being able to provide enough reasonably-matched boats to be used for the Helmsman’s, and the three I best remember were when Gordon Maguire won in 1982 on Lough Derg racing Shannon One Designs, then in the 1970s Harold Cudmore won on Lough Neagh racing Flying Fifteens, and in 1970 itself, a very young Robert Dix was winner racing National 18s at Crosshaven.

Gordon Maguire was the classic case of a talented sailor having to get out of Ireland to fulfill himself. His win in 1982 in breezy conditions at Dromineer in Shannon One Designs, with Dave Cummins of Sutton on the mainsheet, was sport at its best, though I doubt that some of the old SODs were ever the better again after the hard driving they received.

Driving force. Gordon Maguire going indecently fast for a Shannon One Design, on his way to winning the Helmsmans Championship of Ireland at Dromineer in 1982. Photo: W M Nixon

Driving force. Gordon Maguire going indecently fast for a Shannon One Design, on his way to winning the Helmsmans Championship of Ireland at Dromineer in 1982. Photo: W M Nixon

Then Gordon spread his wings, and won the Irish Windsurfer Nationals in 1984 - a great year for the Maguires, as his father Neville (himself a winner of the Helmsmans Championship five times) won the ISORA Championship with his Club Shamrock Demelza the same weekend.

But Gordon needed a larger canvas to demonstrate his talents, and in 1991 he was a member of the Irish Southern Cross team in Australia, a series which culminated in the Sydney-Hobart Race. The boat which Maguire was sailing was knocked out in a collision with another boat (it was the other boat’s fault), but Maguire found a new berth as lead helm on the boat Harold Cudmore was skippering for the Hobart Race, and they won that overall.

A man fulfilled, Gordon Maguire at the beginning of his hugely successful linkup with Stephen Ainsworth’s RP 63 Loki

A man fulfilled, Gordon Maguire at the beginning of his hugely successful linkup with Stephen Ainsworth’s RP 63 Loki

And Gordon Magure realized that for his talents, Australia was the place to be. More than twenty years later, he was to get his second Hobart Race overall win in command of Stephen Ainsworth’s RP 63 Loki, and here indeed was a man fulfilled, revelling in a chosen career which would have been unimaginable in Ireland.

Harold Cudmore had gone professional as best he could in 1974, but it was often a lonely and frustrating road in Europe. However, his win of the Half Ton Worlds in Trieste in the Ron Holland-designed, Killian Bushe-built Silver Shamrock in 1976 put his name up in lights, and he has been there ever since, renowned for his ability to make any boat perform to her best. It has been said of him when racing the 19 Metre Mariquita in the lightest conditions, that you could feel him getting an extra ounce of speed out of this big and demanding gaff-rigged classic seemingly by sheer silent will power.

The restored 19 Metre Mariquita is a demanding beast to sail in any conditions…

...but in light airs, Harold Cudmore (standing centre) seems to be able to get her to outsail larger craft by sheer will-power.

A different scene altogether, but still great sport – Harold Cudmore racing the classic Sydney Harbour 18-footer Yendys

A different scene altogether, but still great sport – Harold Cudmore racing the classic Sydney Harbour 18-footer Yendys

But as for Robert Dix’s fabulous win in 1970, while he went on to represent Ireland in the 1976 Olympics in Canada, he has remained a top amateur sailor who is also resolutely grounded in Irish business life (albeit at a rather stratospheric level). But then it could be argued that nothing could ever be better than winning the Helmsmans Championship of Ireland against the cream of Irish sailng when you’re just 17 years old, and doing it all at the mother club, the Royal Cork, as it celebrated its Quarter Millenium.

It was exactly 44 years ago, the weekend of October 3rd-4th 1970, and for Robert Dix it was a family thing, as his brother-in-law Richard Burrows was Number 2 in the three-man setup. They were on a roll, and how. The manner in which things were going their way was shown in an early race when they were in a tacking duel with Harold Cudmore. Coming to the weather mark, Cudmore crossed them on port, but the Dix team had read it to such perfection that by the time he had tacked, they’d shot through the gap with inches to spare and Cudmore couldn’t catch them thereafter.

Decisive moment in the 1970 Helmsman’s Championship. At the weather mark, Harold Cudmore on port is just able to cross Robert Dix on starboard………Photo W M Nixon

……but Dix is able to shoot through the gap as Cudmore tacks…..Photo: W M Nixon

……but Dix is able to shoot through the gap as Cudmore tacks…..Photo: W M Nixon

…..and is on his way to a win which will count well towards his overall victory over Cudmore by 0.4 points. Photo: W M Nixon

…..and is on his way to a win which will count well towards his overall victory over Cudmore by 0.4 points. Photo: W M Nixon

Admittedly both Harold Cudmore and the equally-renowned Somers Payne had gear problems, but even allowing for that, the 17-year-old Robert Dix from Malahide was the star of the show, and the final points of Robert Dix 9.5 and Harold Cudmore 9.9 for the 1970 Helmsman’s Championship of Ireland says it all, and it says it as clearly now as it did then.

The six finalists in the 1970 Helmsman’s Championship were (left to right) Michael O’Rahilly Dun Laoghaire), Somers Payne (Cork), Harold Cudmore (Cork), Owen Delany (Dun Laoghaire), Maurice Butler (Ballyholme, champion 1969) and Robert Dix (Malahide), at 17 the youngest title holder ever. Photo: W M Nixon

Cudmore's Historical 18 Campaign Ends With Broken Tiller

#haroldcudmore – No sooner had we reported on Cork sailing legend Harold Cudmore's commanding start to the Historical 18 Australian championships in Sydney Harbour than it ended.

Cudmore's chances title were dashed when Yendys capsized off Nielsen Park on the run to Shark Island yesterday afternoon.

The highly fancied Yendys, with Cudmore, one of Ireland's top helmsmen, had been leading Aberdare in a big 20–knot plus nor' easter. The two crossed tacks going to windward up the Harbour, wrote Sail World, Cudmore favouring the western shore, while Winning played the breeze to the east and middle of the Harbour.

When the pair met, Yendys had the advantage, leading Aberdare until just before the YA mark at Watsons Bay, when Winning overtook, his crew quickly hoisting the spinnaker, leaving Cudmore to play catch up.

All was well until Nielsen Park when Yendys tiller broke off and over she went in the gusty winds that produced white caps and swell on the Harbour. Ironically, it was Winning's Rippleside that took on rescue duties.

Royal Cork's Harold Cudmore at the Helm in Historical 18's Australian Championship

#historical18 – Ireland features in this week's Historical 18's Australian Championship in Sydney Harbour thanks to Royal Cork Yacht Club yachting legend Harold Cudmore at the helm of Yendys, one of 11 of the fantastic craft photographed here by Christophe Favreau. Carrying a crew of seven or more these early skiff designs date back as far as 1892.

In a replay of last year's final race, defending Historical 18ft Skiffs Australian champion John Winning steered Aberdare to victory on the first day of the 2015 Championship, after engaging in a race-long battle with Cudmore.

Born and raised in Cork, Cudmore became an internationally famous yacht racing skipper and match racer. Cudmore had success in classes from the International 505, where he placed second in the World and fourth in Europe, through classes like the Half-ton and One-Ton classes where he won the Worlds.

The final race for the Australian Historical championships will be held today.

More stunning photos below and on the Christophe Favreau site HERE

Ireland Hit The High Spot In The Sydney Hobart Race 23 Years Ago

#rshyr – Ireland's fascination with the Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race moved onto a new plane in 1991, when a three-boat Irish team team of all the talents had a runaway win in the Southern Cross Series which culminated with the 628-mile race to Hobart. The three skipper/helmsmen who led the squad to this famous victory twenty-three years ago were Harold Cudmore, Joe English and Gordon Maguire, all on top of their game.

These days, the incomparable Harold Cudmore is still a sailing legend, though mostly renowned now for his exceptional ability to get maximum performance out of large classics such as the 19 Metre Mariquita, sailing mainly in European waters.

But sadly, Joe English passed away just eight weeks ago in November in Cork, much mourned by many friends worldwide. Yet for Gordon Maguire, the experience of sailing at the top level in Australia was life-changing. He took to Australia in a big way, and Australia took to him as he built a professional sailing career. And he's still at it in the offshore racing game as keenly as ever, with 19 Sydney-Hobarts now logged, including two overall wins.

He raced the challenging course of this 70th 2014 edition as sailing master of the Carkeek 60 Ichi Ban, a boat which is still only 15 months old, having made a promising though not stellar debut in 2013's race. Also making a determined challenge was the First 40 Breakthrough with a strong Irish element in the crew led by Barry Hurley, fresh from the class win and second overall in October's Rolex Midde Sea Race.

And high profile Irish interest was also to be found aboard the Botin 65 Caro, the record breaker in the 2013 ARC Transatlantic Race. She's a very advanced German-built "racer/cruiser" aboard which Ian Moore - originally of Carrickfergus but longtime Solent-side resident - was sailing as navigator.

W M Nixon casts an eye back over the 2014 race, whose prize-giving took place in Hobart yesterday, and then concludes by taking us back to 1991, when Ireland moved top of the league in the Offshore Racing World Team Championship on the same occasion some 23 years ago.

It has to have been the most keenly-anticipated debut in recent world sailing at the top level. At last we'd get to see how Comanche could go in serious sailing. When the 70th 628-mile Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race started on Friday December 26th at 0200 hours our time, 1300 hrs local time in Sydney Harbour, this was for real. There may have been 117 boats of all shapes and sizes from 33ft to 100ft in the fleet. But all eyes were on the limit-pushing 100ft Comanche, skippered by the great Kenny Read. The world wanted to see how she would show what she could do when the chips were down, when the racing was straight line stuff, and when some serious offshore battling was in prospect instead of the inshore-hopping mini-test which had been seen in the Solas Big Boat Challenge in Sydney Harbour on December 9th.

In that, the well-tested Wild Oats XI, skippered by Mark Richards, had sailed a canny race to take the line honours win from the other hundred footers. But the majestic Comanche, owned by Jim Clark and his Australian wife Kristy Hinze Clark, had shown enough bursts of speed potential to raise the temperature as the start of the big one itself approached.

And in a brisk southerly at the start, Comanche didn't disappoint. She just zapped away from Wild Oats to lead by a clear 30 seconds and notch a record time at the first turning mark to take the fleet out of Sydney Harbour, and that dream debut was what made the instant headlines on the beginning of the 628–mile slog to Hobart.

The moment of glory – the mighty Comanche roaring down Sydney Hobart at the start to log a record time to the first turning mark. Photo: Rolex/Daniel Forster

No two ways about it – Comanche is clear ahead of Wild Oats XI approaching the first mark. Photo: Rolex/Daniel Forster

But out at sea, with winds strengths varying but mostly from the south for the first day or so, different stories begin to emerge. A grand sunny southerly sailing breeze may provide lovely sailing and pure spectacle in Sydney Harbour. But get out into the Tasman Sea to head south for Hobart, and you find that the wayward south-going current – always a crucial factor in the early stages of the race to Hobart – can be going great guns and making mischief as a weather-going stream, kicking up a steep sea which can be boat-breaking when that last ounce of performance is being squeezed out.

And as previewed here on December 20th, up among the hundred-footers they've been pushing the envelope and then some in boat development and modification. In new boat terms, the mighty and notably beamy Comanche has gone about as far as they can go for now. But with the likes of the former Lahana reappearing as Rio 100 with a complete new rear half, and Syd Fischer's Ragamuffin 100 simply cutting away the hull for replacement with a complete new body unit while retaining the proven deck and rig, we're sailing right on the edge in terms of what the weird mixtures of new and old build can combine for combat when the seas are steep.

Comanche's wide beam gives added power when there's plenty of breeze......Photo: Rolex/Carlo Borlenghi

....but the narrow Wild Oats XI can be as slippery as an eel when the head seas get awkward, and when the wind eased she got through Comanche and into an extraordinary 40 mile lead on the water. Photo: Rolex/Carlo Borlenghi

Not all boats revelled in the bone-shaking conditions of the first hundred miles of beating. Perpetual Loyal (foreground) had to pull out with hull damage possibly caused by an object in the water, but the irrepressible Syd Fischer's Ragamuffin 100 (beyond), with a completely new hull, continued going strong to the finish and was third in line honours Photo: Rolex/Carlo Borlenghi

But this glorious element of larger-than-life characters with boats that are off-the-wall is now an integral part of the RSHYR, which manages to attract an enormous amount of attention thanks to its placing in the midst of the dead of winter in the Northern Hemisphere, while in Australia much attention focuses on what is in effect an entire and familiar maritime community racing annually for the overall handicap prize.

Yet though the course is simple, it's deceptively so. Just because it's mainly a straight line from one harbour to another doesn't mean there aren't a zillion factors in play. And as the race gets so much attention, few offshore events of this length are so minutely analysed, and the first 24 hours provided a veritable laboratory for seeing the ways different boats behave in different wind and sea states with the breeze on the nose.

Thus Wild Oats XI has always had a formidable reputation for wiggling her exceptionally narrow hull to windward in awkward seas for all the world like a giant eel, and the early beating saw her doing that very thing, hanging in there neck and neck with Comanche. Despite her beamier hull, Comanche rates slightly lower than Wild Oats. But if a lull with its leftover sea arrived, her greater volume would become a liability to performance, whereas if the breeze got back to full strength, and particularly if it freed the two leaders, then Comanche would be firmly back in business.

But it was not be. Crossing the Bass Strait with Wild Oats right beside them, Comanche's crew saw their navigator Stan Honey emerge on deck and approach Kenny Read with a thoughtful expression on his face, and an ominous little slip of paper in his hand. It was the latest weather print-out, and it wasn't happy reading for a big wide boat that needs power in the breeze. Before expected brisk winds from the north set in, they'd to get through the lighter winds of an unexpectedly large and developing ridge.

Almost while they were still digesting this bit of bad news, Wild Oats started to cope much better with the lumpy leftover sea, and wriggled ahead of Comanche in her classic style. And the further she got ahead, the sooner she got into increasingly favourable wind pressure. As Read put it after the finish: "For twelve hours, conditions were perfect for Wild Oats, and they played a brilliant hand brilliantly".

Amazingly, the old Australian silver arrow opened out a clear lead of an incredible forty miles before conditions started to suit Comanche enough to start nibbling at this remarkable new margin. And fair play to the Read crew, at the finish they'd made such a comeback that Wild Oats was only something like 49 minutes ahead. But even with the new American boat's slightly lower rating, she was beaten on handicap too, and in the final rankings Wild Oats showed up as having line honours overall and a commendable 5th on IRC in Division 0 - and we shouldn't forget she won the overall handicap honours back in 2012 anyway.

But for 2014's race, for a while it looked as if it might be the Cookson 50s again for the overall win. But although last year's Tattersall's Cup winner, the Cookson 50 Victoire, at first took the Division 0 win with her sister-ship Pretty Fly III second, they were so close that when Pretty Fly got 13 minutes redress for an incident with the Ker 46 Patrice in mid-race, it reversed their placings.

It all came good in the end....after being initially placed second in Division 0, the ten-year-old Cookson 50 Pretty Fly III got 13 minutes of redress for an adverse incident during the race, and that bumped her up to the Division 0 win.

Either way, it was still Cookson 50s imprinted all over the sharp end of Division 0. But they were slipping in the overall rankings, where it was boats in the 40-45ft range which were settling into the best combination of timing and conditions to take the Tattersall's.

And plumb in the middle of them was the First 40 Breakthrough, with her strong Dublin Bay Sailing Club input from the Irish team led by Barry Hurley. Fortunes wax and wane with astonishing volatility as the Hobart race progresses, but gradually a pattern emerges. So though at one stage Breakthrough was showing up only around 30th overall, equally she'd a best show of third.

And all around her on the water were similarly-sized and similarly-rated boats with their race-hardened crews knowing that with every mile sailed and every weather forecast now fallen favourably into place, things were looking better and better for this group to provide the overall winner.

It was a very race-hardened crew which came out on top. It was way back in 1993 that Roger Hickman got his first Sydney Hobart Race overall win in an eight year old Farr 43 which was still called Wild Oats, as original owner Bob Oatley hadn't yet reclaimed the name for ever bigger Grand Prix racers. When he did start to go down that road, the 1985 Wild Oats became Wild Rose, but "Hicko" still owns her. And by the time the Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race 2014 started, he was doing it for the 38th time. He went into it as current Australian Offshore Champion, now he has won the big one on top of all that. Some man, some boat.

The slightly higher-rated Breakthrough was pacing with Wild Oats for much of the race, but as Barry Hurley's report for Afloat.ie told us with brutal honesty, somewhere some time they got off the pace. If you didn't know already of Barry's remarkable achievements - which include a class win in the single-handed Transatlantic Race and the more recent Middle Sea Race success – you would warm to the man anyway for the frankness of his initial analysis of why Breakthrough slipped from being a contender to 12th overall and – more painfully – down to 7th in their class of IRC Division 3.

He promises us more detailed thoughts on it in a few weeks time, something which will be of real value to everyone who races offshore, for the race to Hobart is a superb performance laboratory. And maybe we can also hope in due course for further thoughts from someone on whether or not Matt Allen's Carkeek 60 Ichi Ban, skippered by Gordon Maguire with Adrienne Cahalan as navigator, has what it takes to be a killer.

It's easy for us here in Ireland to look at screens of photos and figures and reckon that Ichi Ban is just a little bit too plump for her own good. But Maguire has twice been key to a Sydney-Hobart overall win, the most recent being in 2011 with Stephen Ainsworth's Loki. And Cahalan's record of success as a navigator/tactician is almost without parallel. Yet though Ichi Ban's 2014 Hobart race score of 8th in line honours and fourth in IRC Division 0 is a thoroughly competent result, it just lacks that little bit of stardust.

Ichi Ban finding her way through the waves on her way to Hobart. If that's not a spare tyre around her midriff, then what is it?

Despite being a "racer/cruiser", the Botin 65 Caro – navigated by Ian Moore – pipped Ichi Ban for third in class.

With the next Rolex Sydney-Hobart Race just over eleven months down the line, let's hope we're proven utterly wrong within the year on the Ichi Ban question. But the whole matter is pointed up by the fact that the boat which pipped in ahead of her in the IRC Div 0 placings in third place behind the two Cookson 50s was the Botin 65 Caro, with our own own Ian Moore navigating on this 65 footer which likes to emphasize her dual role as a racer-cruiser.

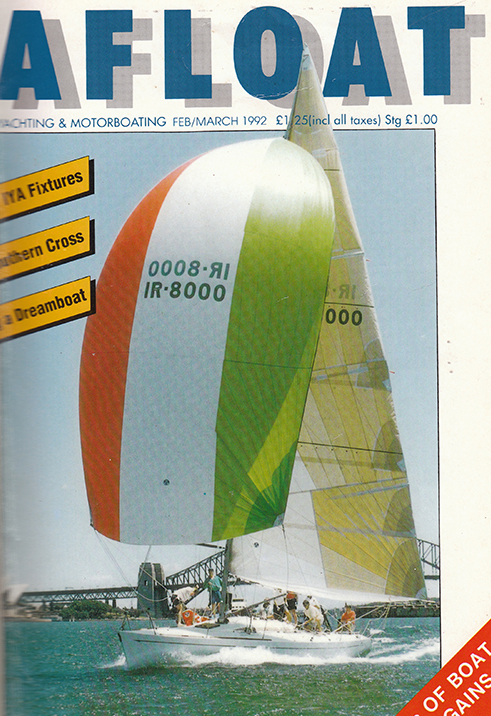

Now there really is food for thought. But in this first weekend of this wonderful new year of 2015, let's remember some of the events of December 1991 as recorded in excited detail in the Afloat magazine of Feb/March 1992.

On the cover is Meath-born John Storey's Sydney-based Farr 44 Atara, around which the Irish Southern Cross team of 1991 was built, as Harold Cudmore was aboard, and he brought out John Mulcahy from Kinsale and John Murphy from Crosshaven.

The small boat of the team was Tony Dunne's Davidson 36 Extension – the owner claimed Irishness through the Irish granny rule, but the matter was put beyond any doubt by Joe English being on board with Dan O'Grady and Conor O'Neill. And then for the third boat they'd Warren John's Davidson 40 Beyond Thunderdome, whose owner was happy to be Irish if they'd let him, and to put the matter beyond doubt his vessel was over-run by Howth men in the form of Gordon Maguire, Kieran Jameson, and Roger Cagney, with Dun Laoghaire's Mike O'Donnell allowed on board too, provided he behaved himself.

In the Southern Cross Series of 1991, the Davidson 40 Beyond Thunderdome was raced for Ireland by Gordon Maguire and Kieran Jameson. Thunderdome was top of the points table when she was knocked out with a dismasting in the final inshore race, and was unable to race to Hobart.

It was an accident-prone series, with Beyond Thunderdome dismasted in a tacking collision with one of the Australian boats with just three days to go to the start of the Hobart Race. There simply wasn't time to get a replacement mast, let alone tune it, but at the last minute the jury decided the Australian boat was at fault, and allowed Beyond Thunderdome average points not only for that race in which she'd been dismasted, but also for the Hobart Race which hadn't even yet been sailed.

In a final marvellous twist to the story, as Thunderdome couldn't race to Hobart, Gordon Maguire was drafted aboard Atara to add helming strength for the big one. Atara had only been a so-so performer until the big race. But Cudmore and Maguire – that really was the dream team. And it gave the dream result. Atara won the 1991 Sydney-Hobart race overall by a margin of one minute and 50 seconds. It was one of the closest results ever, but it was a close shave in the right direction for Ireland. The Irish party in Hobart to welcome 1992 was epic. And Gordon Maguire's sailing career was set on a stellar course.

Our magazine edition of February/March 1992 cover-featured John Storey's Farr 44 Atara, overall winner of the 1991 Sydney-Hobart race with the dream team of Harold Cudmore and Gordon Maguire on board to give Ireland the win in the Southern Cross Series.