#oldestyacht – Serenely she sits, with all the heightened elegance of a still beautiful grand dame who, despite a hectic youth, has lived long and well to take her place in a position of respect, verging on reverence, within the community. But then anyone, whatever the life they may have led, would be deserving of some sort of special appreciation if they'd managed to reach the age of 224 still in reasonably good order, still looking much as they did more than two centuries ago. Yet that is the case with the 26ft schooner yacht Peggy. When you attend upon her in her home in Castletown in the Isle of Man, it's as if time has stood still since the 1790s.

We sailed over to the Isle of Man recently for the Peel Traditional Boat Weekend. As it had been expanded to include the final Irish Sea gathering for the Old Gaffers Association Golden Jubilee, it was felt that the least we could do, before the revels began, was to pay our respects to the ultimate old gaffer of them all, across at her home port on the south coast of the island. And if the Peggy of Castletown isn't the oldest yacht in the world in more or less intact order, then we'll be fascinated to hear of any vessel having a better claim. For by any standards, the Peggy is extraordinary.

Thus we'll leave an account of the fantastic party in Peel for another day. It will be ideal for the depths of winter when such memories of enjoyment deserve to be savoured at leisure. But the Peggy deserves to be highlighted right now. For the fact is that if you're into boats and those who sailed them and their history, then the Peggy blows your mind. The story of her origins, of her adventures in sailing, and of how she has survived for more than 200 years, would the stuff of legend if it didn't happen to be completely true.

The story of the Quayle family of Bridge House right on the harbour in the ancient Manx capital of Castletown is long and distinguished. In the 18th Century, John Quayle was a leading figure in the administration of the Isle of Man. But though his son George Quayle (1751-1835) was a member of the Manx parliament, the House of Keys, for 51 years, he was also something of a Renaissance man, his interests as a successful merchant and ship owner including the co-founding of the Isle of Man's first bank, while his inventive talents were such that he won a gold medal of the Society of Arts.

George Quayle (1751-1835)

Despite the challenging nature of the waters around the Isle of Man, he was also an enthusiastic amateur sailor. So when the impressive Bridge House was being completed in 1789, he saw to it that its eastern end included a private dock accessed through an arch from Castletown Harbour, the dock in its turn giving access to a "boat cellar" in which he planned to have slipping facilities for a 26ft sailing boat he was having built nearby.

Bridge House, Castletown, IOM. George Quayle's quarters were on the right hand side of photo, and the blocked-off entrance to the Peggy's dock is at lower right. Photo: W M Nixon

It may well be that, like the J/24 some 174 years later, the size of the new boat Peggy was dictated by the size of the garage available. Whatever, there's no doubt she's a very neat fit in the boat cellar. George Quayle then provided a complete maritime unit around his new boat's berth, as he created his own personal quarters around it independent of the family home, the main feature directly above the Peggy's cellar being a fine living room replicating the Great Cabin of a sailing ship.

The first sight of the Peggy when you descend to the boat cellar is memorable, though it takes some time to grasp that this is a boat built 224 years ago. Photo: W M Nixon

The stern is completely typical of its era Photo: W M Nixon

The sections reveal a hull with real speed potential. Note the original spars stowed on wall on right. Photo: W M Nixon

The interior reveals how the topsides were raised to increase sail carrying power. Photo: W M Nixon

With his new boat comfortably housed, and his own quarters cleverly created to shelter him from the demands of busy family life, most folk would have taken things easy for a while. But George Quayle was a bundle of energy. Although the boat was built in 1789, with the demands of completing the big new house, he doesn't seem to have started sailing the Peggy – named after his mother – until 1791. But once she was in action there was no stopping him, both in spirited sailing, and in re-configuring the boat to improve performance. So although the lower part of the hull of the Peggy is probably much as it as when she was built in 1789, as he increased the sail area of the already massive schooner rig he also raised the topsides in order to carry the extra cloth without having her fill. Even then, he still had extra canvas "boards" to keep the sea at bay.

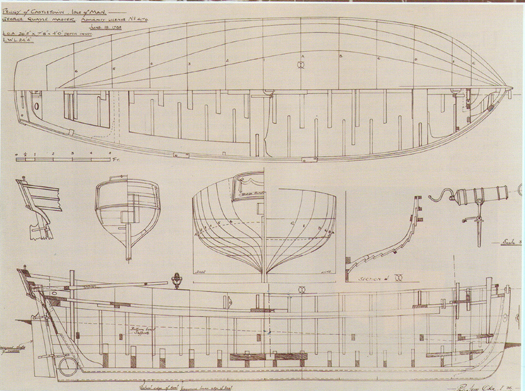

The construction details and hull lines were taken off in the 1930s after Peggy had been released following a century of entombment

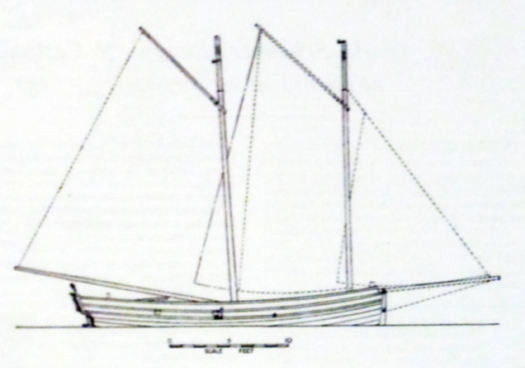

The sail plan is arguably a primitive version of that set by the schooner America 55 years later

The Peggy – complete with miniature yet very real armaments, as French privateers were active in the Irish Sea – was always considered a yacht, and Quayle was keen to race her and further improve performance. Thus he was soon experimenting with "sliding keels" to combat leeway, and the reputation of the Peggy became such that a challenge was set up to sail in a regatta against the only flotilla of other racing yachts within reach, across at Windermere in the English Lake District.

George Quayle was related to a leading figure in Windermere sailing, John Christian Curwen, who had a couple of sailing pleasure boats imported from the Baltic. Also on the lake was a supposedly hot sailing machine owned by one Captain Heywood. So in 1796, Peggy sailed across to Cumbria, and was carted up the half dozen or so miles from the inner reaches of Morecambe Bay to the lake, which is 128ft above sea level.

It was quite an effort, and as yacht racing organisation was only in its infancy in 1796, the results weren't totally clearcut, though it seems that the Peggy outsailed everything else by several country miles. Intriguingly, two other boats from this pioneering regatta have also survived, though not so well as Peggy. These were the two Baltic boats owned by John Christian Curwen. They were still intact until the 20th Century, but then were fire-damaged while in store. The sad remains of both were on display in a corner of the Windermere Steamboat Museum when I was there around twenty years ago, but largely ignored. Much more interesting was the discovery that George Quayle's relation John Christian Curwen was in turn related to Fletcher Christian of Bounty notoriety, who was of course a Cumberland man. Up among the lakes, they were happy to tell us that there's no way Fletcher Christian stayed on Pitcairn until the end of his days – he got home to the lakes some way or other, so it's said.

But meanwhile the Peggy only just made it home to the Isle of Man after her successful foray to Windermere. She'd a real pasting in the Irish Sea beating back to Castletown, but in typical style George Quayle turned this to best advantage, cheerfully reporting in a letter that the "sliding keels" so improved windward performance that they safely made it back to port.

The sailplan on the model is one interpretation of the abundance of spars available in the boat cellar Photo: W M Nixon

Today, in the boat cellar at Bridge House, you can see the Peggy and all the features which made her such an able flyer. She still has the slots through which George Quayle lowered his primitive centreboards, and on racks on the wall are the original spars she carried when in her racing prime. This indeed was and is a formidable racing machine, and it's no exaggeration to assert that, in her miniature style, she was an early example of the type which reached its supreme development with the schooner America.

And she has survived through a fortuitous miracle of preservation. The exact timing and circumstances in which it all happened are not precisely clear, but we know that after George Quayle died in 1835, the Peggy was entombed in her boat cellar, with the seaward entrance walled up. In time, the little dock was filled in, and the archway through to Castletown harbour closed off. Yet with the pervading salty air, this provided an ideal environment for boat preservation. When it was all opened up again in the 1930s, there was the Peggy, still in remarkably good order, still the same little ship which had successfully completed such a gallant expedition to Windermere in 1796.

Today, George Quayle's quarters in Bridge House accommodate the Manx Nautical Museum, with the Peggy – now formally owned by the Manx nation - the prime exhibit. But with every passing year, she becomes ever more important, so much so that 2014 will see a comprehensive project to conserve her, and in time - let us hope - put her on more accessible display with her full racing rig in place.

With imaginative design, it could possibly be done by putting a clear roof over the little dock. I didn't pace it out when we were there a couple of weeks ago, but guessing from the photos, it should be just about feasible to accommodate her there with all sail set.

The former dock, now filled in, where Peggy was berthed before hauling into the boat cellar - note her stern just visible in doorway, while the windows in the room above reflect sailing ship Great Cabin style. This former dock could be re-configured for use as a covered display area where the newly conserved Peggy could be put on show fully rigged. Photo: W M Nixon

And after 224 years, she surely deserves a proper display. But for now, there are the intriguing challenges of conservation. Most of the timber is in remarkably good order, but the fastenings need replacing, as apparently they are "mineralising". That sounds remarkably like good old-fashioned rust to you and me, but "mineralising" is a word to cherish. So it won't surprise you to learn that, after the earnest piety of our visit to the Peggy, my shipmates then threw themselves into the festivities and fabulous hospitality of the Peel Traditional Boat Weekend with such enthusiasm that we were undoubtedly in a mineralised condition as we slugged our way back home across the Irish Sea.