#OppiEuros2014 – This weekend sees a truly international sailing event taking shape in Dun Laoghaire, with the Optimist European Open Championship attracting 250 young sailors from 44 nations (32 European, 12 others). They will take to the waters of Dublin Bay in a little boat which is one of the key strands in the fabric of world sailing. W M Nixon takes a look at the Opty back-story, and outlines the front runners in the Euros and the home team.

Once upon a time, there was an American magazine called The Saturday Evening Post, which lived up to its name by arriving in millions of households across America in the last postal delivery of each week. It provided a focus for family life with its homely mixture of entertaining, informative and educational articles. And as it was the most widely circulated weekly in America, it had the resources to employ talented artists who each week evocatively illustrated the very best of American life with a strong family slant.

But it's a long time now since the demand for post and printed material were such that a publication of this quality could be a viable proposition. The Saturday Evening Post ceased to be a weekly in 1963, and for a while was reduced to a quarterly. These days, it is published six times a year as an exercise in nostalgia by The Saturday Evening Post Society. But while it may now only be a shadow of its former self, the weekly illustrations produced at its height by its team of artists have endured as highly-regarded works of art in themselves. And nothing more perfectly captured the essence of American home and small town life at its very best than the paintings of Norman Rockwell who, in a 50 year career with the magazine, created more than 300 of The Saturday Evening Post's distinctive covers. It was popular art at its very best.

Yet even an all-embracing magazine of this calibre could not cover every good news story going on in America during its glory years from 1920 to 1960, and there were some gems which escaped Rockwell's technically brilliant attention. So if there's ever a competition to create The Greatest Norman Rockwell Picture Never Painted, let us suggest that "Building The First Optimist Dinghy in Clearwater, Florida" should be right up there for consideration. Indeed, as the International Optimist Dinghy Association is such a thriving, prosperous and global body, I'd suggest they commission it themselves, as doing so would create a neat story in itself.

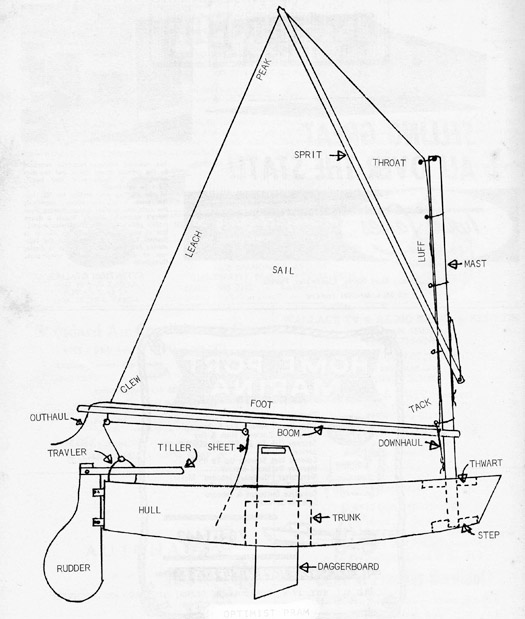

"Neat" is the word which most often comes up in talk of the Optimist, and of course in America it carries wider connotations than the simpler European notion of tidiness. At just 8ft long, the little sailing pram is neat but deceptively simple, and the people who brought it into being in Florida in August 1947 were quiet geniuses who did much good work mostly by stealth, but knew when to beat a drum when it suited their cause.

It started with a recently returned World War II veteran, Major Clifford A McKay, noting that while his son Clifford Jnr aged 12 much enjoyed the landbound wheeled soapbox races for young people organized by the Clearwater Optimist Club (one of those classically American community groups like the Rotarians and the Lions), the boy's most strongly developing interest was sailing as a crew in the local Snipe dinghy class.

Back in 1947, even in Florida there wasn't the money to splash about on any sport in which your child showed an interest, so the Major got fired up with the notion of creating the cheapest possible sailing boat – a floating soapbox - that could get the local young people afloat in their own boats. His own interest in boats was purely for fishing, but he proved he could turn his inventive mind to anything, and he outlined his requirements to the local boatbuilder Clark Mills, who happened to be going through a quiet late summer period at his workshop.

Clark Mills (1915-2001), designer and builder of the first Optimist

The first drawings for the Optimist – it was to be built with two sheets of 8 x 4 plywood

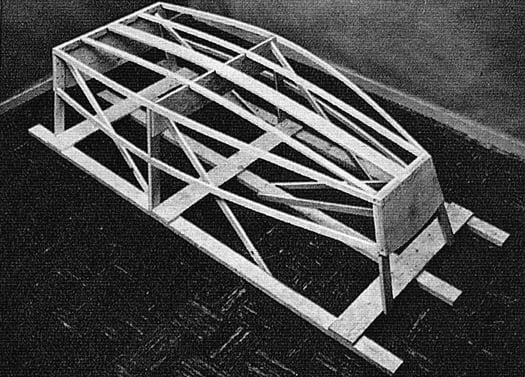

This framework was the mould on which the first Optimists were built by Clark Mills

Within a fortnight, Mills - the quintessential all-American can-do character – had created a bright red 8ft sailing pram, the dimensions dictated by the fact that it was to be made from two sheets of 8ft x 4ft ply, the rig dictated by the utter simplicity of a sprit setup, as they'd hoped to make the sail from a square bedsheet.

The bedsheet was the first notion to be scrapped – the local sailmaker and his wife were soon producing economy sails. But as for the basic design, it was a winner from the start. Yet even in his wildest dreams, young Clifford Mackay Jnr could never have thought, as he sailed that first able little prototype out on Clearwater Bay, that he was sailing a boat which would go on to become a cornerstone of global sailing.

Young Clifford McKay with one of the first Optimists at Clearwater Bay, Florida in 1947

The fleet is racing....thanks to sponsorship from neighbourhood businesses in 1947, the Clearwater Optimist fleet was soon in action

Local needs came first. The class took off in Clearwater when Major McKay and his committee secured sponsorship from neighbourhood firms for the building of 28 boats. That it was all happening outside the stuffy constraints of established sailing became evident when the local paper reported an early series. It simply mentioned that the Optimist prams of the Clearwater Sun and WTAN Radio Station had tied on points. Blatant sponsorship and advertising were anathema to traditional yachting (even if Lipton and Jameson had boosted sakes of their tea and whiskey with sailing success), but the idea that the sponsor would be named but the helmsman ignored went way beyond the pale.

Be that as it may, it worked in getting the show on the road, and the Clark Mills Boat Works was soon churning out Optimists, while Major McKay was successfully promoting the idea throughout Florida. Reaching a wider public didn't dent the little boat's good image in any way - in fact, it enhanced it. Other builders were to find that building a competitive Optimist was in no way as easy as "Clarkie" Mills made it seem, and it was recalled that his Boat Works had produced some super-fast Snipes.

As for Mills himself, he had no doubt his interpretation of McKay's outline had produced something very special, and quipped: "I think I'm the best designer in the United States. I'm damned good. I've got the splinters and the backache to prove it....."

It might have been out of character for him to admit the profound satisfaction that the Optimist's success in opening up the world of boats had given him in his varied life from 1915 to 2001, but he couldn't suppress his love of sailing: "A boat, by God, it's just a gleamin' beautiful creation. And when you pull the sail up on a boat, you've got a little bit of somethin' God-given. Man, it goes bleetin' off like a bird wing, you know, and there's nothin' else like it."

There were other small boats becoming available which were broadly similer to the Optimist in concept, and in Ireland at Skerries local sailor Brian Malone, a naval architect with BIM (the Sea Fisheries Board) created a tiny children's sailing pram dinghy which he called the Measle, as every kid would have it sooner or later. But while the Measles had to be robustly built to cope with Irish conditions, by comparison the Optimists seemed light as a feather, and by the 1950s they were going international in an unexpected direction, having taken off big time in Scandinavia.

Rapid international expansion began when the Optimist became widely accepted in Scandinavia in the 1950s. By 1967-68, Peter Warren of Denmark (left) was twice world champion, using an Elvstrom sail.

That such a stronghold of classic yacht design should adopt the utilitarian little American boat speaks volumes for the Optimist's versatility, and the fact that at only 8ft, moving the boats around was not a major logistical challenge. Nevertheless some countries held out against the Opties' easy appeal. But by the early 1960s even the traditional strongholds in the south of England were sharing the momentum, and a regatta in the Hamble River in 1962 set the seal on the Optimist's British success, with the first fibreglass boats also starting to appear.

This regatta in the River Hamble in 1962 confirmed the Optimist's growing popularity in England

A mighty long way from a creek in Florida – a major Optimist championship under way at St Moritz in Switzerland

Today, practically every sailing family in the world goes through its Optimist phase while there are kids under the age of 15 in the lineup, with the prime years with national and international aspirations being 13-15. Thus the most intense Optimist individual window is only two to three years. In some families, the involvement can be almost total, while in others it's just a case of having an Optimist or two about the place.

We were in this situation for about twelve years in all, and it ended on something of a high with the youngest son showing his entrepreneurial skills by becoming a part-time Opty dealer long before he'd a driving licence. This meant his parents had to drive him to other sailing centres where the class was developing, and then stay in the background while he struck a deal with some nervous parent anxious to provide a hot boat for their demanding child. Major Clifford McKay and Clarkie Mills – you've a lot to answer for........

Ireland has punched way above her weight in Optimist involvement, and the development of the international association has seen key players such as Robert and Helen-Mary Wilkes of Howth, and Curly Morris of Larne, making dedicated input in order to keep the Optimist class relevant to the needs of modern sailing, while Robert Wilkes took time out to record the history of the class in a gem of a book which has provided much of the material for our look at the early years.

Adaptation and innovation have been central to the Optimist's continuing success. Thus although the convenient size of the little boat has been a bonus in times past, even at just 8ft long it is now becoming so expensive to move about internationally that one of the attractions of the Europeans at Dun Laoghaire will be the provision of a large charter fleet already on site.

A glimpse of the future – the charter boats which will be used at Dun Laoghaire by a significant number of young sailors

As for the site, Dun Laoghaire has enthusiastically woken up to the fact that it can provide the kind of club and accommodation package which topline modern events expect. The Royal St George Yacht Club is the host, while the Royal Marine and Kingston Hotels have combined forces to provide what is in effect an Olympic village.

If you want the ultimate measure of the Optimist's central role in sailing, it's worth noting that six of the female European Olympic dinghy medallists in London 2012 had participated in Optimist European Championships, the male "graduates" included triple Olympic medalist Iain Percy, and worldwide you'll find that top people in sailing in many different areas of the sport are more than happy to remember their Opty days - it's just part of what our sport is all about.

In the coming days, it's the defending girls' champion, Maria Turin of Slovenia, who'll be the main focus of attention, for if she succeeds, it will make it three in a row. As for the boys, Tytus Butowski of Poland is the defending champion.

So far, Ireland's best result came in 1992 when Laura Dillon of Howth was fourth, while in 2011 Peter McCann (Royal Cork) placed 5th. Like youth itself, there's something essentially ephemeral about top level Optimist racing, but for the year or three that's in it, Ireland's lineup for 2014 is: Sarah Cudmore (Royal Cork), Dara Donnelly (National YC), Gemma McDowell (Malahide YC), Grace O'Beirne (Royal St George YC), Clare Gorman (National YC), Harry Bell (Royal North of Ireland YC), Alex Buckley (Skerries SC), Michael Carroll (Kinsale YC), Loghlen Rickard (National YC), James McCann (RCYC), Alex O'Grady (Howth YC), Daniel Hopkins (HYC), Jamie McMahon (HYC) and Peter Fagan (SSC).