#classicboat – The preservation of old boats can be a contentious issue, particularly so when the vessel is of significant historical interest at several levels, such as Erskine & Molly Childers' ketch Asgard. Technical and academic question arise as to when a refit become a major refurbishment, when does a preservation become a conservation, or when is a restoration veering into being a re-build? Alternatively, should you simply cut your losses and build from new, but using the original plans if the boat meant something very special to you and the larger maritime community? W M Nixon takes a look at three special boats of Irish interest which are currently at an important changes of course in their voyages through life.

Xanadu is no more. Espanola is seeking a new home. And Periwinkle is born again. And no, we're not launching into some imitation of the rolling cadences of Coleridge's Kubla Khan. On the contrary, we're just considering the current circumstances of three very different boats which have the shared factors of being at a significant juncture in their lives, and having strong links with Ireland.

My own first view of Xanadu was coming round the point at Courtmacsherry about a dozen years ago, and being much taken by a couple of big white raked masts vivid against the green West Cork background – clearly, it was an American ketch. Then close up, her handsome dark blue hull, with a delicately understated clipper bow, confirmed her Transatlantic appearance. And the elegant counter, with its raked and almost elliptical transom, reinforced this conclusion.

She was definitely of a type, and yet she seemed different. Something said that this classic yacht was neither a Francis Herreshoff nor a John Alden. Herreshoff was renowned for his large clipper-bowed Bermudan rigged ketches, of which the best known was the legendary Ticonderoga – "Big Ti". And though Alden was most famous for his schooners, he had shown he could turn his hand to classic ketches with raked masts and very positive clipper bows if that was what the client wanted.

But this striking yacht, newly making Courtmacsherry her home port just after the turn of the Millennium, didn't quite fill the Herreshoff-Alden bill. For sure, she had all the typical features. But they were in an elegantly under-stated style which gave her an almost mysterious air, and made you wonder just who might have been the designer, and when.

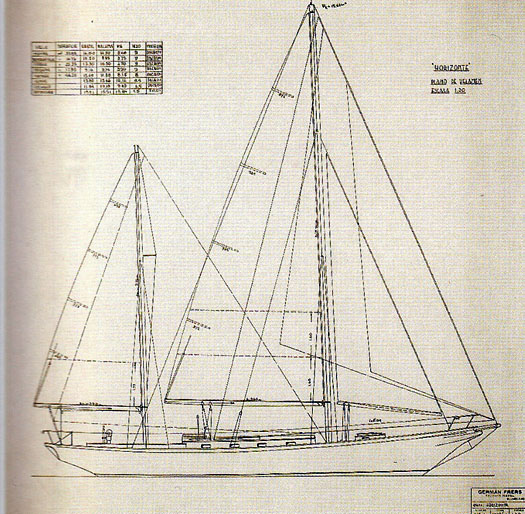

The story was pure gold. The 48ft Xanadu had been designed by the Argentine legend German Frers Senr, patriarch of a yacht design dynasty which is now well into its third generation. The origins of her hull above water was a sweet clipper-bowed ketch called Horizonte which old man Frers had designed for his own use in 1936, but one of his friends and customers liked the boat so much, and was prepared to pay even more to have her, that Frers never became her owner-skipper.

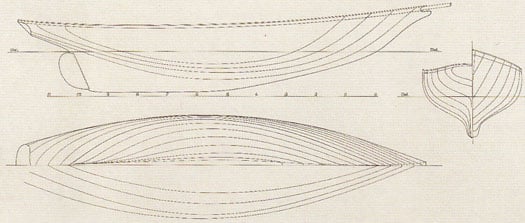

Argentinian designer German Frers designed the 48ft Horizonte for his own use in 1936, but she was snapped up by an enthusiast for his designs, so it wasn't until 1982 that he was able to build the boat as Xanadu for himself (though she too was to be snapped up), and this time she was given a different under-body, with long fin keel and centerboard, and skeg-hung rudder.

The 1936 hull profile for Horizonte.

In fact, it wasn't until 1982, and after owning several other boats of a more ocean-racing orientation to his own design, that Frers Senr had another look at the possibility of Horizonte for his dreamship. In re-sketching her, he retained the handsome above water profile. But as his son German Jnr was now cutting a mighty swathe through the international yacht design scene, with the 1981-built 51ft Moonduster for Denis Doyle of Cork only one of many hyper-successful boats at the front of the fleets, presumably the father took the son's advice on changing Horizonte's underwater profile to a long fin keel with centreboard, and a skeg hung rudder.

Xanadu as she was in June 2014 – the underwater hull profile is very reminiscent of the German Frers Jnr F&C 44 design. Photo: W M Nixon

Certainly the resulting underwater shape is almost exactly the same as the famous Frers performance cruising ketch, the Argentine-built F&C 44, of which Ireland has a fine example in Otto Glaser's Tritsch Tratsch IV at Howth. But the new Xanadu was slightly larger, like Horizonte 16.3 metres (48ft LOA), with a wider stern and more volume in every way – she was big for her size. And once again no sooner was building in progress in steel in Buenos Aires than someone else wanted her, and made an offer that couldn't be refused.

An early owner was a colourful character whose private life was such that the boat, at various stages of completion, seems to have been shifted back and forth across the River Plate between Argentina and Uruguay in order to keep her out of the clutches of a scorned wife who was in pursuit of her share of all the owner-skipper's assets. But eventually Xanadu, as she had evocatively become, found her way into American ownership and embarked on a very civilized 15-year voyage round the world, which she completed with style.

Norman Kean found her for sale in Annapolis. Very much a Scotsman and an enthusiastic member of the Clyde Cruising Club, his work as an industrial chemist had brought him to the DuPont plant in Derry, and for several years he was an active member of Lough Swilly YC at Fahan, starting with a Sadler 25 which he completed himself from a bare hull and deck, with which he undertook round Ireland cruises, the long haul south to Brittany, and a venture north to the Faroes. The latter won him an award from the Clyde Cruising Club, but with his new base he was soon also active in the Irish Cruising Club, and then he up-graded his boat size to a Sigma 33 for six years.

But with the DuPont plant at Maydown facing the closure of most of its operations, he took up an offer of a posting to the main American plant. And when that contract was in turn fulfilled, he took a look at another offer with the company in the late 1990s, but decided that it was time to take the alternative lump sum offer of money, and a new road in life. He and Geraldine had the vision of buying a suitable boat from among the thousands on offer at the US East Coast's three main "boat markets" of Newport RI, Annapolis and Fort Lauderdale, and sailing her back across the Atlantic to run an owner-skippered-charter operation in Southwest Ireland.

Their ideal was a 42-44ft ketch, but then they saw Xanadu in Annapolis, and were smitten. Certainly she was a bit tired, but tired in a well-cared-for way. With a successful charter business keeping them busy each summer, they would have the resources to bring her back to showroom condition over the winter. So they brought her back across the Atlantic, loving their fine big ship even more with every mile sailed, and set about going into business with a base at Courtmacsherry.

And they came up against the brick wall that is Ireland's Department of Transport. After years of struggle and ultimate failure, Norman now looks back on it all with a sort of ironic amusement. "There mustn't be a worse place than Ireland in the whole world to set up an one-boat owner-skippered-charter operation" he wryly observes. "They just don't get it, and they just don't want to get it. Obstructions and objections and prohibitions are put in your way at every turn. They just want you to go away, and leave them in peace to deal only with companies, and the bigger the better".

Certainly the cultural clash between the spirit of the Irish Public Service, in which the ideal is to rise without trace or trouble through the ranks until you reach a level with a highly desirable pension and the possibility of early retirement, is about as different from the Norman Kean approach to life as possible.

But being a man of much energy and vision, he was soon finding other outlets, and became the Honorary Editor of the Irish Cruising Club Sailing Directions, raising them to a new level. He and Geraldine made a formidable research and production team, and for several years, as the new rigorously up-dated editions appeared at remarkable speed, it was the handsome Xanadu which featured as the cruising yacht in the photos in the Directions, showing she had somehow found her way into obscure anchorages, many of them tiny places by comparison with her hefty size.

Xanadu on survey and research service for the ICC Directions at Inishvickillaune in the Blasket Islands. Photo: Geraldine Hennigan

You wouldn't think you could get into a place as small as this, but research is everything....Xanadu in the tiny harbour of Carnlough on the Antrim coast. Photo: Geraldine Hennigan

But without the income of a skippered-charter operation, maintaining a steel ketch of this size and age was becoming impossible. In order not to be impossibly heavy, steel yachts have to be built with only 6mm plate, which is fine for strength but leaves nothing extra to allow for the local corrosion which is almost inevitable and difficult to detect when complex accommodation is fitted into hulls sprayed internally with insulation. Thus even with high level maintenance, it is reasonable to expect that a steel yacht will last only about fifty years without major work being undertaken.

With Xanadu, it was the more visible bits of the ship – the cockpit coamings and cabin sides, for instance, the places in the spray areas - which were most prone to rust. But there were also enough questionable spots, albeit minor, on the hull itself, hidden away by bulkheads, internal furniture and fittings and so forth, which were a cause for real concern. For as long as he could, Norman replaced or repaired the corroding areas, but it was a growing challenge – the ship seemed to be in rapid decline.

The surveying and research for the ICC Directions continued with boats loaned by members – Norman at work in Lough Foyle in 2013 aboard the 35ft Witchcraft provided by Ed Wheeler of Strangford Lough. Photo:W M Nixon

Xanadu was taken temporarily out of commission, but the ICC's research duties continued with boats loaned by members on all coasts of Ireland. Yet every time Norman and Geraldine returned from this absorbing work, they had to face again the problems with their own boat. It was decision time. They had to put Xanadu up for sale, ideally to someone who had the resources to refurbish a still eminently saveable classic. Or else they'd have to watch her rust away before their very eyes.

But the economic recession was in full swing. And selling a boat from remote Oldcourt Boatyard in far West Cork was a very different proposition from frequent showing to the boat-keen crowds who mill about places like Annapolis. The months passed, the years passed, there was interest, but there was nothing which converted into anything realistic. They made the decision that Xanadu was not going to make the 50 years which is the normal life-span of a fully-maintained steel yacht. Instead, she would end her days at the age of 32 while there was still a bit of dignity to it.

It's making the decision which is the really painful part. Once it's made, you're absorbed by the challenges faced in stripping a complex 48ft structure down to a shell, and selling the bits and pieces for sometimes surprisingly good prices, while keeping some special parts for possible incorporation in a new boat.

The last days of Xanadu. Seen here in June 2014, she'll be completely gone within a fortnight from today. Photo: W M Nixon

But as of this weekend, Xanadu is a bare shell, though still at home in the easygoing world of a friendly local boatyard. However, within a fortnight, this empty shell will be moved to the very different world of a scrapyard, and the final coup de grace will be delivered in a matter of hours.

In our modern world, in which such harsh events are kept hidden by professionals from sensitive eyes, we now and again need to reflect on the final reality. But despite Xanadu's fate, there are still many people who continue to preserve old boats for whatever reasons, and by very different means. So we'll round out this piece with the two very different stories of two historic boats which had very special links with Dun Laoghaire and Dublin Bay.

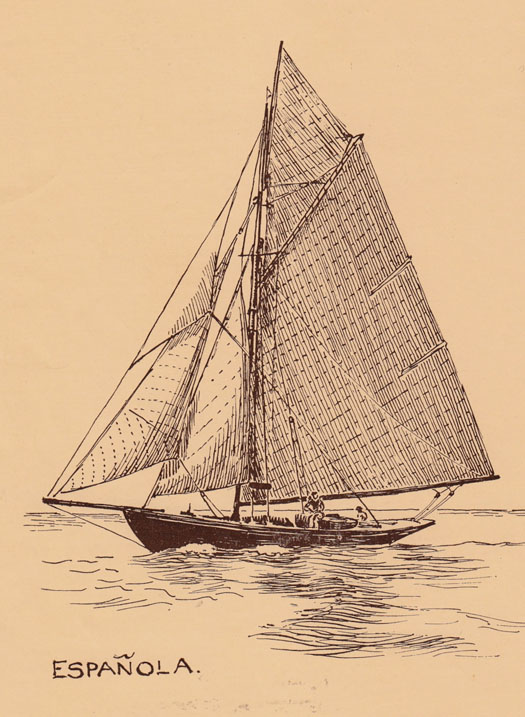

Espanola has sailed through this blog before. A 47ft cutter designed and built by Sam Bond at Birkenhead on the Mersey in 1902, she was originally called Irene VII, but in 1912 she was bought by Herbert Wright of the Royal Irish YC on Dublin Bay who'd been a founder owner in the Dublin Bay 21 class the year Irene was built. He actually cruised his DB 21 Estelle, which must have been an austere business, but certainly Irene seemed luxurious by comparison. And when the King of Spain visited the RIYC clubhouse during a formal visit to Ireland in 1912, as Irene on her moorings was the nearest boat to the clubhouse of any comfortable size, he was taken aboard her to see an Irish yacht, as he was himself a keen sailing man. Almost immediately, Herbert Wright - a fast-thinking stockbroker - re-named his new boat Espanola, and she has been Espanola ever since.

Espanola as she was in 1929. (from a drawing by Billy McBride)

In Herbert Wright's ownership, she made some notable cruises, indeed he was so highly regarded in the Irish cruising community that when the Irish Cruising Club was formed with a cruise-in-company of just five yachts to Glengarriff in 1929, Espanola was one of them, and she came back to Dun Laoghaire as the new ICC Commodore's yacht. It was a role she continued to fill for a dozen years, so it would be quite something of she was still around for the ICC's Centenary in 2029.

Since leaving Ireland in the 1940s, she has had a varied life, but for many years now, she has been owned by Martin Birch, a lecturer at Lancaster University. This means his home port is Preston on the Lancashire coast with, its huge tides and shallow channels. Espanola is very deep draft, so if you set out to choose an unsuitable home port for her, Preston would come well up the list, except that the folk in Preston Marina have adopted her as their sort of pet classic yacht, so Martin has had every assistance possible to keep his big boat in pristine condition.

Espanola as she is rigged today, with a more manageable gaff ketch configuration.

Espanola is currently afloat under these high quality covers in Preston in Lancashire. Photo: Martin Birch

That said, when planks needed replaced she had to be taken to the Menai Straits and one of the boatyards there which are carving out a formidable reputation for quality work on classic and traditional craft. Getting Espanola to the Straits was no bother, as Martin has made some fine cruises with her, notably to the Outer Hebrides. So Espanola is in good shape for a boat of her age.

But after 25 years of total dedication in looking after this big vessel in challenging circumstances, Martin has decided it's time for a change, and Espanola is for sale. However, for someone looking for a flawless classic yacht pedigree, while her hull is totally authentic, Espanola's rig has now been changed from a big gaff cutter to an easily handled ketch, though still gaff rigged, while her accommodation has been made much more comfortable and roomy by the addition of an elegant full-length coachroof.

So today's Espanola is not totally as she was in 1902, but her full history has been traced by Martin Birch, and he has written a privately-published book about it which very effectively reveals why this is an important boat, though a challenge for any owner. However, if you're interested I'll put you in touch with him, but this isn't one for the faint-hearted.

But then, keeping any classic or historic vessel in seagoing shape is never something for the faint-hearted, so we'll conclude with a totally different approach to the methods adopted in the case of Xanadu and Espanola. It must be nearly ten years now since the six surviving Alfred Mylne-designed Dublin Bay 24s were spirited away to Brittany for a planned complete re-furbishment and their intended re-emergence as classic playthings for the mega-rich at a new resort centre to be built in the south of France.

The re-born class was to be known as the Royal Alfred 38s, as 24ft is only their waterline length, and people go by LOA these days. As to the Royal Alfred, it supposedly sounds more posh than Dublin Bay, and it was at a committee meeting of the Royal Alfred Yacht Club in Dublin in 1934 that Gordon Campbell, the second Lord Glenavy and owner of the Dublin Bay 21 Garavogue, first outlined the concept – and a very advanced concept it was too – for a larger more modern Bermudan-rigged one design for racing in Dublin Bay, and capable of some modest cruising.

By 1938, Dublin Bay Sailing Club took over the project, and a design was commissioned from Alfred Mylne in Glasgow. But though building work started in Scotland in 1939, World War II delayed everything, and the class didn't have their first race at Dun Laoghaire until 1947. They were an immediate success - they filled Gordon Campbell's brief to perfection, and for more than five decades they'd great racing in Dublin Bay, they also logged some truly remarkable cruises, and for good measure they did the business racing offshore, with one of them the overall winner of the RORC Irish Sea Race in 1963.

But the setup in Dun Laoghaire does not favour the continued existence of a class of 38ft classic wooden yachts, so the DB 24s had definitely run out of steam when they were swept up by the Royal Alfred 38 consortium. Then the recession arrived, and all sorts of rumours circulated about the boats being held as security against debts, of them being piled away any old how in a warehouse near Benodet in Brittany, and of lots of other things, none of them good news.

That is, until somewhere over a month ago, when I heard from an acquaintance with a Classic in the Balearics that he'd heard a rumour a restored Dublin Bay 24 had been seen sailing in the inner reaches of the Bay of Biscay, and seemed to be very much at home there. This I thought rather good news, as it seems to me to be a much more appropriate setting for these very special boats than the French Rivera with its harsh sun, where the classic yachts are so large that the Dublin Bay 24s, or whatever they were to be called, would be virtually invisible.

The new Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle sailing off La Turballe, August 2014

For once, it's good news, albeit with a slightly sad tinge. The slightly sad note is that the Dublin Bay 24 Periwinkle, which never left her birthplace in Scotland and was only united permanently with her sisters when they were all shipped to Brittany several years ago, is now absolutely no more. Well, her tiller still exists and is in use, but whether that's the original tiller from 1948 is another matter. And her lead ballast keel still exists. But the rest of Perwinkle is totally gone, burnt to ashes. Yet Periwinkle still sails, and is looking very well indeed.......

Last glimpse of the 1948 Periwinkle, September 2012

It's quite some story. In 2012, the original Perwinkle was bought by the Francois Vivier organization in France, which specializes in classic boat-building to the highest professional standards, and also creating designs – some of them distinctly quirky, and some which can be built by amateurs. The ideals behind it all have taken off in such a big way in France and abroad that there's an almost religious fervor to some of Vivier's adherents, and the story of Periwinkle will in no way diminish this.

For they took the original Periwinkle, and with a team of qualified shipwrights and trainees, they meticulously took her apart bit by bit in order to see how she had been built, and to give them the information to build an exact replica, albeit in different wood technologies such as the use of laminated frames.

Perwinkle built anew – the laminated frames go into place

Looked at a certain way, it's all a bit morbid – we're in the surgeon's dissecting theatre here. And no, I don't know if they had an audience, but it's for sure they would have had no troubling assembling one. Then, with all the information to hand, and with every last little dismantled bit and piece for further confirmation, Francois Vivier drew out new plans for the re-construction. Periwinkle re-born took to the water in August this year, and she looks only gorgeous.

The new Periwinkle on her launching day – she'll be known as a Dublin Bay 24

With her teak decks looking immaculate, the new Perwinkle goes afloat for the first time.

You'll be glad to hear she's known as a Dublin Bay 24. And such is Francois Vivier's following, I wouldn't be at all surprised to hear of a new class in the making on France's Biscay coast. For with Gordon Campbell's vision, the further experienced input of the committees of both the Royal Alfred Yacht Club and Dublin Bay Sailing Club, and Alfred Mylne's genius, they got one marvellous yacht.

So there it is. The three choices with an important but ageing classic yacht. Euthanasia. Or the continued dogged preservation against all the odds. Or a complete re-build. Not easy, any of them.

No, you're not seeing things, this is undoubtedly a very new Dublin Bay 24. But it would be impossible to quantify how much she cost, as the entire dismantling and building project has been part of a larger training progamme.