#americascup – The 35th America's Cup series will be staged in Bermuda in 2017, and already the first team – Ben Ainslie Racing – is starting to settle into its base in the islands at the beginning of a developing process which, it is hoped by locals, will contribute significantly and sustainably to an economy which is by no means as prosperous as the popular image of Bermuda would suggest.

Yet past experience of being involved with the America's Cup circus suggests that while there are definitely immediate and highly visible benefits, they're ephemeral and are more than offset by a hidden but very definite downside. And the pace of the event at its peak is at such a level that almost immediately afterwards there's a sense of anti-climax and recrimination which can poison a sailing centre's atmosphere for years. W M Nixon considers how sailing's most stellar event affected Irish sailing, looks at a more recent continuation of this story, and then takes up the tale of an old boat whose class's health suffered collateral damage from America's Cup fallout.

It was while tracing the story of Tern, a 37ft William Fife-designed Belfast Lough One Design built by John Hilditch of Carrickfergus in 1897, that we stumbled into what is arguably an example of the America's Cup having a seriously damaging effect on local sailing.

Somehow or other, Tern has survived, and is currently being restored to international standards in Palma, Mallorca. But it was when a couple involved with her restoration came to Ireland shortly after Christmas to spend some time researching her history that we had to face the fact that while Belfast Lough's involvement with the America's Cup is seen as a glamorous and still-celebrated era, as far as everyday sailing is concerned it did little but harm.

The context is intriguing. Belfast in 1897 was the Mumbai of its day. From a population of around 80,000 in 1850, by 1910 its unprecedented expansion through massive industrial innovation and development, built largely around ship-building and linen manufacturing, had seen numbers soar towards 300,000. The city was a byword for pollution, over-crowding, and ill health, but equally it was noted as a place where anyone with energy and an innovative manufacturing idea was expected to have made their fortune within ten years, and around three or four years to start reaching towards wealth was seen as a not unreasonable aim.

In such a frenetic and ambitious atmosphere, sailing on Belfast Lough developed apace, and it developed ambitiously and competitively for all that the lough, while providing splendid sailing water, lacked any really good natural anchorages. New boats and new boat types appeared with bewildering rapidity, and a sort of one design keelboat concept was being accepted by the early 1890s in order to make good racing accessible to keen young men at a reasonable price. There may have been much underlying wealth about, but spending it on extravagances like large and expensive yachts was frowned upon.

By 1896 a young whiskey distiller called James Craig (he later became Lord Craigavon) was promoting the idea of a strict One Design keelboat around 23ft LOA, and about 16ft LWL, designed by the great William Fife in Scotland, but built on the lough by John Hilditch at his Carrickfergus boatyard. As the pioneer of the concept in the locality, Craig called the new class the Belfast Lough No. 1 OD, but the first boat to the design, his own Fugitive, was barely finished before the One Design keelboat ideal was taken up with enthusiasm by another group which decided they wanted something to the same concept, but much larger.

These new boats, the first of which were rapidly built in time for the 1897 season, were almost exactly enlarged versions of Fugitive, but were all of 37ft overall and 25ft waterline. In a case of Might is Right, the bigger boats now became the Belfast Lough Number Ones, while Fugitive and her sisters were demoted to Number 2, and by the early 1900s they'd slipped still further to become the Number 3s when yet another class appeared, this time around 31ft LOA.

There were enough of the new 37ft Number Ones afloat to make a real impact on Clyde Fortnight in 1898, and as they were well able to sail across Channel to do so, they were arguably the world's first offshore one design. The previous year, some had visited Dublin Bay, where they so impressed the locals that they were the inspiration for the Dublin Bay 25s, to the same lines but built to a higher specification and with lead ballast keels, rather than the Belfast Lough boats' cast iron keels.

Whimbrel on the Clyde in 1898. They'd the potential to be the world's first offshore one design, but offshore racing hadn't yet been invented. Whimbrel is currently undergoing restoration in Bordeaux. Photo courtesy Gordon Finlay/RUYC

By the middle of the 1898 season, the Belfast Lough One Designs were in all their glory, and our header photo from that season shows a class which surely promised at least a decade of great racing. Yet their peak years barely stretched beyond the turn of the century, and within five years they scarcely existed as a class. Well before the Great War broke out in 1914, they were starting to spread near and far in a scattering which was to continue post war and in most cases ended up in their eventual demise. But remarkably, two have survived and both are undergoing restoration, Whimbrel Number 8 in Bordeaux and Tern, number 7, in Mallorca.

Patricia O'Connell and Alan Renwick live in Palma where he is a master craftsman with Ocean Refits while she – a former Honorary Secretary of a Georgian preservation society in Dublin – has undertaken the tracing of Tern's story, as Tern's restoration is Alan's current project. They arrived in Dublin in the dying days of 2014, and by the time they headed back to Palma well into January, they'd spent time in Cork and Northern Ireland following the old boat's elusive trail, and had also called in Howth to see Ian Malcolm's Howth 17 Aura, which was built in Hilditch's yard within a year of the construction of Tern.

Still going strong. The 1898 Hilditch-built Howth 17 Aura off Carrickfergus Castle for her Centenary, April 1998. With her sister-ships, she then sailed the 90 miles home to Howth. Like Tern, she is number 7 – and like Tern, there's an element of confusion with sail number 2. Photo: David Jones

The original five Carrickfergus-built Howth 17s still sail together as part of a thriving class of twenty Howth 17s. But the impressive class of eight Belfast Lough One Designs from the same era have been remembered for more than a hundred years only as photos on the walls of the Royal Ulster Yacht Club. What went wrong?

The America's Cup – that's what went wrong. In the early years of sailing's premier trophy, there was remarkable Irish involvement. After the schooner America won it with a race round the Isle of Wight in 1851, it took a while to establish a format for races to try and wrest it back from the New York Yacht Club in contests in America. During the 1870s, there were three challenges – two from Britain and one from Canada. Then in the 1880s there were three from Britain and one from Canada, the final one from Britain in 1886 being through the Royal Northern YC of Scotland, but that was because the owner's wife was Scottish – the husband was Lt William Henn whose family home was on the north shore of the Shannon Estuary.

But while the Henn family's hefty cutter Galatea was another unsuccessful challenger, at least she was seen in the waters of the Shannon Estuary. Yet although the first two challenges in the 1890s were by racing machines owned by a yachtsman whose ancestral pile was also on Shannonside, neither boat was seen anywhere near Adare Manor, the home of Lord Dunraven on the south side of the Shannon Estuary, whose two campaigns in 1893 and 1895 were unsuccessful and increasingly acrimonious.

With the passage of time, it becomes increasingly clear that Dunraven got a decidedly raw deal. But in the feverish atmosphere of rapid economic expansion in the 1890s, the world was more interested in pushing ahead with new projects rather than putting right old wrongs. Someone who saw the developing publicity and business potential in the America's Cup was Thomas Lipton, the Scottish-born grocery magnate whose American empire was thriving with a combination of his sheer love of hard work, and gift for publicity.

Lipton had noted the extraordinary level of public interest in Lt & Mrs Henn's "family" challenge in 1886 – they'd actually lived on board the Galatea at he time. But much more importantly, he'd noted the international crisis which arose from the Dunraven affair, and cannily realized that anyone who could smooth the waters with a good-tempered America's Cup challenge would attract acres of favourable coverage, regardless of the actual result.

That said, as a highly competitive individual, there's no doubting he was keen to win. But even though all five of his yachts called Shamrock making his America's Cup challenges between 1899 and 1930 were unsuccessful, with some being much more closely fought than others, he remained resolutely good humoured throughout, and expansion of his retail empire continued unabated. But what's less widely known is that while the America's Cup Shamrocks were numbered I to V, there was a sixth Shamrock, an un-numbered 23 Metre, which raced as his private yacht. It's said that when she didn't perform as well as she should have, the old man could be very grumpy indeed.

But that's all in the future. Here we are in the latter half of the 1890s, and on Belfast Lough this wonderful new class of 37-footers is spreading its wings, thriving on the fact that although the owners lived all round the lough and were members of one yacht club, the Royal Ulster YC founded 1866 and given the "Royal" in 1869, they could feel at home wherever their boats happened to be, as the RUYC had no clubhouse. This was a true sailing club, fixed only to good sailing water, and with the Belfast Lough Number Ones they could sail it well.

It was too good to last. Thomas Lipton was a man in a hurry. He knew that he needed a yacht club of international standing through which to make his first America's Cup challenge. But as he was of humble birth and very much in trade instead of benefitting from inherited wealth, there were few yacht clubs open to him. However, his parents had come from Monaghan, not only in Ireland but particularly in Ulster. In the can-do atmosphere of Belfast in the 1890s, it was indicated that the Royal Ulster might be receptive to his interest. He was soon a member, and plans were roaring ahead for an 1899 Challenge with Shamrock I.

But the RUYC had taken a cuckoo into its nest, or rather its virtual nest. It emerged that a virtual nest was not enough for the aspirations of a serious America's Cup challenger, he needed a real nest. Lipton was soon insisting that his America's Cup challenge, now irreversibly under way, would required the RUYC to have a proper clubhouse impressively sited above the waters of Belfast Lough where it was assumed he would very soon be the defender in the America's Cup.

The new RUYC clubhouse was completed at the behest of Thomas Lipton in 1899 after just 18 months work.

And he got his way. An impressive arts and crafts tower-topped clubhouse design was drawn up by James Craig's brother, the architect Vincent Craig, and the new RUYC clubhouse was opened in April 1899, having been built in 18 months flat. Well – not quite flat. They were in such a hurry for completion that there wasn't the time to entirely level the hillside site on the Bangor waterfront where the new clubhouse was built, and even today the ground floor is on two or three different levels.

That said, it's an impressive building to have been put up in such a short time, and somehow they achieved a sort of instant antiquity with it – today it seems much older than its 116 years, and it has always been thus.

But antique or otherwise, it doesn't seem to have been desired by all the members. There were 150 of them, yet only 30 contributed directly to the cost of the new clubhouse. And others took their sailing elsewhere. We live in hope of finding letters or a sailing diary from this period which will tell us what was really going on, for official club committee papers only cover what was on the agenda and recorded in the minutes. Thus even if there was an almighty row going on about the very fact of the somewhat cavalier building of this new clubhouse, at the time it would have been something known to everyone, and talked about by everyone, yet not written down simply because everyone knew of it, and it didn't happen to be directly pertinent to the business of the day. And anyway, once the clubhouse was in being, that was that – the best thing was to get on with living with it.

Yet the fact is that a distinct division arose in sailing along the south coast of Belfast Lough. The conspicuous Royal Ulster YC in Bangor became the public face of yachting in the area. But further up the lough at Cultra beside a roadstead anchorage, what had been a modest canoe club developed in 1899 into an amalgamation of the Ulster Sailing Club with the Cultra Yacht Club to become the North of Ireland Yacht Club, and by 1902 – by which time Lipton had already unsuccessfully challenged twice for the America's Cup through RUYC – the new place at Cultra had become the RNIYC, with a modest clubhouse aimed exclusively at serving its members' sailing needs rather than following grandiose ideas of international yachting campaigns for plutocrats who were only very seldom about the place, if at all.

Inevitably some of the best sailing men in the north were involved with this move to Cultra where many had always anchored their boats in any case, and others had followed. Whether or not the active membership of the RUYC was seriously depleted we can only guess. But the fact is that the relatively small membership of a provincial yacht club had somehow to find, within its membership, the essential people with the necessary talent and experience to provide the back up committee and officer services for Lipton's America's Cup Challenges, with the next one coming along as soon as 1903.

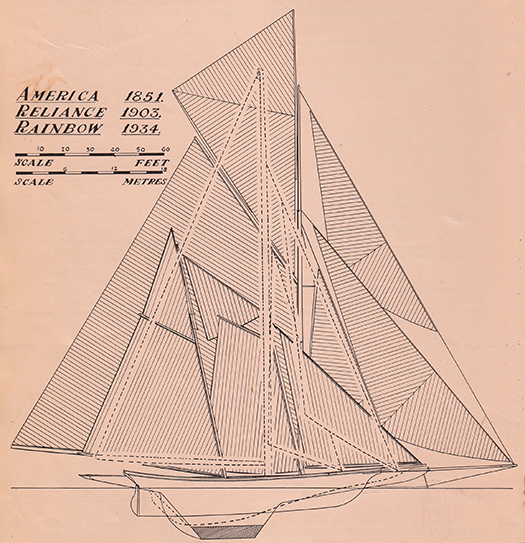

America's Cup design development 1851 to 1930. The Challenge Committee of the RUYC may have come on the scene 48 years after the era of the schooner America, but they still had to cope with the challenges posed by the design development from boats like Reliance in 1903 to the J Class Rainbow in the 1930s.

The drain on RUYC personnel resources was heavy in an era when time-consuming Transatlantic voyages by ship were required for the challenger's committee to meet with the committee of the defending New York Yacht Club. Something just had to give, and it seems to have been the level of personal sailing within RUYC, and particularly with the Number One Class.

The new RNIYC setup at Cultra was establishing its own modest new 22ft OD class, the Linton Hope-designed Fairy Class (also built by Hilditch), so they may well have seen the much larger Number Ones as simply too large, and tainted by the new vulgarity of the RUYC. Whatever the reason, the Belfast Lough Number One Class was a brilliant flame which burned only briefly as a class, even though the boats survived individually with most of them becoming fast cruisers.

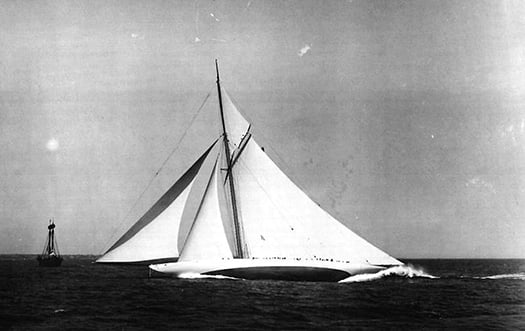

But as for the America's Cup, it continued on its melodramatic way, with skulduggery par for the course. After 1903's unsuccessful challenge, when Shamrock III found herself ill-matched against the hyper-giant Reliance, the RUYC committee may have returned home to recuperate and gather strength for Lipton's next campaign. But he was scheming other ideas, and it has been only relatively recently discovered that, unbeknownst to RUYC, he was in preliminary negotiations with the Royal Irish YC on Dublin Bay to organise his fourth challenge.

Lipton and the RUYC thought they'd an impressive boat with the Fife-designed Shamrock III in 1903, but this is what they came up against in America – mega-boat Reliance

From a purely commercial point of view, you can understand his thinking. The formerly despised Irish community in the US was expanding rapidly in numbers and prosperity by 1904. Coming in with a challenge through the Royal Irish Yacht Club would hit more market targets than the narrower appeal of a Royal Ulster challenge. It was crude but shrewd business thinking. But fortunately for goodwill in the sailing community, nothing came of it. Challenge 4 through RUYC was slated for 1914, but with the Great War breaking out it was held off - with the radical and very promising Shamrock IV designed by Charles E Nicholson stored in the US – until 1920, with Shamrock IV defeated by the narrowest margin. And then in 1930 came the last challenge, the first with the J Class, but again there was defeat, this time for Shamrock V.

And thus 1930 saw the end of the Royal Ulster YC's tumultuous three decades affair with the Holy Grail of sailing. Since then, other clubs have had their collective finger burnt by the America's Cup. But it usually promises more than it gives. Most recently, sailing has been bluntly reminded of its limited appeal as a spectator sport, even when packaged as America's Cup Plus. The 34th series in San Francisco may have provided some of the most exciting racing ever seen in the event's 164 year history. It made great television for aficionados. And it may have attracted 150,000 shoreside spectators over the length of the series. But let's get it into perspective. San Francisco's Number One tourist attraction is Alcatraz. This island with its former prison fortress linked to the likes of Al Capone and other adornments of American society attracts around a million visitors a year. No matter which way you slice the numbers, that's quite a few more than the America's Cup, it doesn't cost nearly as much, and it's much less trouble to run.

Which goes some way to explain why those of us who live for this crazy old vehicle sport of ours retreat into the happy dreamworld of old boats and their winding journeys through life, often to a wonderful re-birth. And the story of Tern is a classic of its kind. From Belfast Lough she headed some time or other to Cork, we don't quite know when, but we do know she was converted to a yawl for greater ease of handling in 1914. And she was certainly in Cork in the 1920s and 1930s owned seemingly by a loose syndicate, as different owners appear at different times depending on what event she is being entered for, and in 1929 she was one of five yachts taking part in the Irish Cruising Club's Founding Cruise-in-Company to Glengarriff, owned by Capt P F Kelly.

Happy days. Aboard Tern in cruising style, complete with enormous dinghy on the starboard deck, on her way to the founding of the ICC in Glengarriff in 1929 with Captain Kelly and Dr Dan Donovan enjoying the sail

Tern in Falmouth, July 1990. Rot had long since set in within her long and elegant Fife counter, so it had simply been chopped off. Photo: W M Nixon

Tern being overcome by the heat in Andraitx in Mallorca, October 2012. Photo: Patricia Nixon

Yet by 1947 according to Lloyds Register she was in Dun Laoghaire, owned by two members of the National Yacht Club, C E Hogg and M Healy. And then she turns up in Falmouth Harbour in the 1970s and stays there for some time, but she was restored to being a cutter, not with full rig but her mizzen had to be done away with, as there was rot in her long elegant Fife counter, so it was simply chopped off to become like a Laurent Giles stern.

It was then in a little yard in a hidden creek off Falmouth Harbour that she had her first major restoration, and with that she went to the Mediterranean. But by the Autumn of 2012 she was seen in Andraitx looking a bit sorry for herself, and very much for sale. And there she was bought and taken into the specialist yard in Palma, and at the end of December 2014 Patricia O'Connell and Alan Renwick turned up in Ireland and began a pilgrimage.

Alan Renwick and Ian Malcolm aboard the latter's Aura in Howth, December 30th 2014. Aura had Tern have just one year age difference, but the same builder. Photo: W M Nixon

This took them to Howth to see the Hilditch-built Aura (like Tern, she's number 7, and like Tern, at one time her mainsail was mixed up with a number 2). Then it was down to Crosshaven to meet Royal Cork archivist Dermot Burns, who was a fund of information and original material abut Tern's twenty-plus years on Cork Harbour. Then on north to Belfast Lough for a large gathering in the Royal Ulster, a party built around the Charley family, one of whose ancestors owned Tern in 1910, and also brought in folk like noted northern sailing historian Michael Clarke of Lough Erne, and Fife yachts historian Ian McAllister who now lives in Carrickfergus. So you can well imagine that information and ideas overload was a constant risk. But Patricia and Alan survived, they got back to Palma in one piece, the work on Tern resumed, and the Tale of Tern goes on.

There's a Fife hull in there somewhere. Tern in the restoration shed in Palma