Next Tuesday, May 31st, marks the Centenary of the outbreak of the Battle of Jutland off the northern coast of Denmark, the greatest sea battle of World War I (1914-18). In terms of the fire-power of the 250 vessels in action – many of them the most powerful first class battleships of their time – it may still be the greatest naval battle ever fought, even if its results were not clearcut during the engagement itself. For Jutland subsequently ensured that Imperial Germany’s surface fleet stayed largely in port, thereby closing off seaborne sources of supply. This contributed to the inevitable outcome of the Armistice on November 11th 1918, though not until after there has been much further slaughter on land between the warring armies.

Of the many ships which were present at Jutland, only one has survived. This is the C-class light cruiser HMS Caroline, which from the 1920s onwards served as the Belfast HQ of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. She was decommissioned from this role some years ago, and there was some doubt as to her future. But her unique position as the only survivor of Jutland has seen a flurry of activity on the ship for the past eight months and more, with the Caroline getting the benefit of a €20 million Lottery Heritage grant for her restoration as the centrepiece of a Naval Museum which will start to go public from next Tuesday. W M Nixon takes up the story, and goes on to provide the unexpected follow-up of how a leading player in the Howth gun-running of 1914, a man honoured in Irish history, was last weekend celebrated in Belgium as a great British hero of World War I.

In terms of shared memories handed down through the generations, a hundred years is little enough time. But Centenaries offer an opportunity for taking stock, a time for re-shaping attitudes to acknowledge the fact that combatants in any conflict had a shared humanity, however opposed their views and objectives may have been. The recent unveiling in Glasnevin of the impressive Memorial which lists everyone killed in the Rising of 1916, regardless of which side they were on, was a significant step. And next week’s shared ceremony in Belfast at HMS Caroline, which will include the Irish Naval Service in an official capacity, will acknowledge the many Irish sailors - sailors from what is now the Republic - who lost their lives at Jutland just five weeks after the Easter Rising in Dublin.

HMS Caroline in her original form – she was commissioned in December 1914

The enormity of the carnage and endless stalemate of the Great War, and the industrialisation of the means of fighting with the institutionalisation of those who found themselves involved, is something almost beyond our grasp today, enjoying as we do our lives of multiple choices and continually available diversions. And when you read the obnoxiously gung-ho editorials of the pro-war newspapers of a hundred years ago, cheerfully exhorting young men to an almost certain and very unpleasant death, it is to realize that the past is indeed a different country.

Yet it’s a country which we have inherited and must try to understand. To do so, perhaps the most helpful way is through a contemplation of the individual stories involved, for in total war individuality is one of the first casualties.

But the individuality of each sailor is quickly lost in the sheer weight of statistics. The death toll at Jutland may have seemed minor by comparison with the wholesale slaughter which occurred when some new army offensive was launched on the Western Front. But the figures are chilling nevertheless, with Royal Navy sustaining more than 6,000 deaths. This was more than twice the German losses, but although Britain had lost such prestige ships as the largest battleship HMS Queen Mary (she blew up with 1266 deaths – only 18 survived), the Royal Navy was still powerful enough after the battle to ensure that the German fleet was confined to port.

From the 1920s, HMS Caroline served as the Belfast HQ of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. Her accommodation was decidedly limited, so later additions included what looked to casual observers to be sheds rather than cabins.

Work under way restoring and where necessary replacing HMS Caroline’s deck

Of the death toll in the British side at Jutland, at least 350 were from Ireland, and while it’s reckoned that 90 were from what subsequently became Northern Ireland in 1921, recent research suggests that 266 were from what became the Free State and is now the Republic, with nearly half of them being from the great naval port of Cork Harbour.

At Belfast Harbour, the personal touch will be manifest as more than 200 relatives of those from Ireland who were lost at Jutland will be attending next Tuesday’s ceremonies, whose staging will quite rightly cause us to confront yet again the sheer mindless horror of the Great War. But last weekend in Belgium, we were remembering people – sailing people to be precise – who had gone off to the Great War in an almost festive frame of mind.

In my case, involvement came through Asgard and the Howth gun-running of 1914. We all know about Erskine and Molly Childers and Mary Spring-Rice and their professional crew of Charles Duggan and Pat McGinley from Gola Island in Donegal. But it was the sixth member of Asgard’s crew, Gordon Shephard, a keen amateur sailor and personal friend of Erskine and Molly Childers, who remained something of a mystery.

Shephard’s involvement in the gun-running was an even greater mystery to his fellow officers in the British Army, for he was a career soldier of impeccable background, Eton-educated and a product of Sandhurst military academy. But he had a liberal frame of mind which strengthened as he grew older, and he was - like Childers - a strong supporter of the Irish Home Rule movement. So when it was proposed to smuggle a consignment of 1500 German guns into Ireland aboard Childers’ Asgard and Conor O’Brien’s Kelpie in response to the importation into the north in April 1914 of 24,000 German guns by the anti-Home Rule Ulster Volunteer Force, Shephard was very much involved, though he requested he be called “Mr Gordon” during it all, as the name Shephard might have alerted the authorities and jeopardised his military career.

That Shephard was part of an English social elite there is no doubt, and the Irish people involved were definitely pillars of society too. So much so, in fact, that in advance of last night’s 185th Anniversary Dinner of the Royal Irish Yacht Club in Dun Laoghaire, I was told that of all Ireland’s yacht clubs it was the RIYC which was most closely connected to the gun-running. For although Erskine Childers bought his first cruising yacht, the 2.5 Rater Shulah, from G B Thompson of the Royal St George YC in 1892, and subsequently bought a Water Wag for use on Lough Dan in what was then Kingstown in 1894, he never seems to have been a member of any Irish yacht club, whereas Conor O’Brien was to be closely associated with the Royal Irish, and the 600 guns from his old ketch Kelpie were transferred to the auxiliary yacht Chotah owned by Sir Thomas Myles RIYC, who subsequently landed them on the beach at Kilcoole County Wicklow.

Sir Thomas Myles with friends and crew aboard his sailing cruiser Faith (RIYC) in Dublin Bay in the late 1920s. In 1914, with his 60ft auxiliary-powered Chotah, he took on board the 600 guns brought from the Belgian coast by Conor O’Brien on Kelpie, and landed them on the beach at Kilcoole, County Wicklow. Photo: Courtesy RIYC

Yet apart from the fact that since 1911 this mystery man Gordon Shephard had been a fellow-member with Erskine Childers in the London-based Royal Cruising Club, with his subsequent wartime career with the Royal Flying Corps being one of great distinction, little enough was know about him until enthusiastic amateur historian Michael Branagan discovered that a Memoir of Gordon Shephard, edited by Sir Shane Leslie, had been privately printed in 1924, and a copy of it was in the library at Castle Leslie in County Monaghan.

Michael being Michael, he got himself up to the depths of Monaghan and spent what must have been the most of a day making two good photocopies of it, one of which he gave to me, and thus we both now know more about Gordon Shephard than you’d have thought possible, yet somehow he remains as elusive as ever.

For here was a young Army officer who accidentally shot himself in the foot during some horseplay in the Mess, yet his charm and abilities were such that he was able to continue his army career despite being described by one fellow soldier as “the least military man I ever met”.

At Eton he’d been criticised by his tutor as being too relaxed in his attitude to discipline, yet when he took up cruising with great enthusiasm around the age of 20, his light hand of authority proved exactly right for getting the best out of his crews. In 1911 he was awarded the world’s premier cruising trophy, the RCC Challenge Cup, for an extraordinary voyage to the furthest point of the Baltic with his 9-ton yawl Sorata. And then in 1913 he was awarded it again for his even more famous Autumnal venture of bringing Erkine and Molly Childers’ Asgard from Norway to Conwy in North Wales via the Shetlands and the Outer Hebrides through severe storms, including a genuine Force 11.

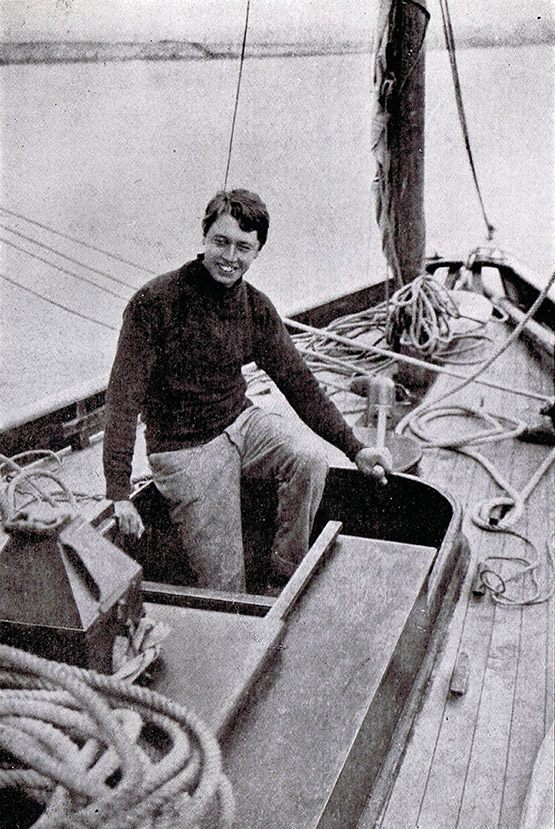

Gordon Shephard and Erskine Childers aboard Asgard with the Howth guns, July 1914. Although everyone else was keen to have their photo taken, Shephard reckoned that as a serving army officer, it might not be a good career move to appear full face

It was typical of the affection in which Shephard was held by his many friends that, owing to his leave running out, he’d to return to his regiment leaving Asgard in Conwy, yet not once did Childers complain about it. This was despite the fact that Shephard had been meant to deliver Asgard to Southampton. But far from complaining, Childers helped to put together the Shephard log which was awarded the cup.

When the gun-running proposal came up in May 1914, Shephard doesn’t seem to have hesitated at all in volunteering to go along. He was engaging company on board, with a nice line in humour, and in her personal log of the venture, Mary Spring-Rice records how he volunteered to cook the supper in rough weather when Asgard was wellnigh uninhabitable with the cargo of guns stowed everywhere. Shephard gallantly weighed in with the cooking of an enormous omelette. But when it was almost ready, he decided it needed an extra little something. So he tipped in the most of a tin of Lyle’s Golden Syrup. We’re told that Syrup Omelette tastes better than it sounds…..

Shephard played a key role in the actual landing of the guns at Howth, for although he’d to leave Asgard at Milford Haven for a week back on duty with the army, he was one of the few who knew the details of Childers’ berthing plans, and on that breezy July Sunday lunchtime a week later, he was stationed at the end of the East Pier in Howth for the crucial task of taking and securing the lines as Asgard came into port with the fresh wind right up her stern. Molly Childers made a superb job of the helming, but without those lines smartly made fast ashore, it could have gone very wrong. Yet thanks to Gordon Shephard on the quayside, all went like clockwork.

But within a week, the Great War had broken out, and with his military future now in the Royal Flying Corps which he had joined on its formation in 1912, his formerly pedestrian rate of promotion became meteoric. He had a magnificent war - if there is such a thing – and by 1917 at the age of 31 he had become the youngest Brigadier General in the British Army with many decorations including a Legion d’Honneur from the French for heroic service in 1915.

Yet he remained the same unassuming Gordon Shephard, refusing to become a “chateau general” despite his obvious talents in aviation innovation and strategic planning. Instead, he stayed with his units, and regularly visited each one at their various airfields, flying himself in a little scout plane to make regular personal visits to sort out problems and encourage his pilots.

Nevertheless the war took its severe toll on him. When we look at the photo of Gordon Shephard aboard Sorata in 1911, we’re looking at a photo of a youthful 25-year-old sailing enthusiast. But when we look at the photo of Gordon Shephard when he became a Brigadier-General just six years later, we’re seeing someone who looks about 50, and a badly worn 50 at that.

He died soon afterwards in a flying accident. He’d set out as usual on 19th January 1918 to fly himself to several of his units, but just short of the first airfield on his route, his little plane came spinning out of the clouds, and he suffered ultimately fatal injuries in the crash.

Without a care in the world. A youthful Gordon Shephard aboard Sorata aged 25 in 1911 Photo courtesy Castle Leslie

Brigadier-General Gordon Shephard in 1917 – at 31, he was the youngest Brigadier-General in the British Army, but he had pushed himself so hard that he looked more like 50

His funeral was an impressive affair, attended by an awesome array of the top brass, yet in the huge losses of the Great War, the name of Gordon Shephard slipped from view. As he left no family, he would have been forgotten were it not for the Howth gun-running and those two impressive awards of the Royal Cruising Club’s Challenge Cup in 1911 and 1913.

Belgium’s Royal North Sea Yacht Club at Ostend. While most of its fleet is cruisers and offshore racers, the club also has a class of vintage International Dragons. Photo: W M Nixon

This year, the RCC decided to hold a rally to Ostend to remember its many members who died in the Great War, and visit some of the battle sites of the Western Front over which Gordon Shephard had flown on many of his highly-valued reconnaissance flights. It was last weekend, and there was a gathering in the Royal Nord See Yacht Club, with a goodly part of the assembly was made up of people who’d sailed there. The pace was set by Commodore Henry Clay, who’d voyaged from Chichester Harbour in West Sussex with his wife Louise in Highlander, his little slip of an H Boat. Yet despite their cramped accommodation, the Commodore stepped ashore looking immaculate.

Dragon manoeuvres in Ostend. Immediately beyond is the H Boat Highlander, which RCC Commodore Henry Clay and his wife Louise had sailed to the Rally from Chichester Harbour in West Sussex. Photo: W M Nixon

Setting the sartorial example. Despite being aboard the smallest boat in the fleet, the Commodore was the neatest of the lot of us. Photo: W M Nixon

With our trio from Ireland, we’d already done the quintessential Belgian thing with a visit that day to the ancient watery city of Bruges nearby, which is even more wonderful than you’d imagine if approached in the right spirit. And then in the RNSYC we were treated to a classic Belgian fishing port dinner of majestic cod with all the trimmings, and during it those of us with some knowledge of the club’s war heroes talked of them and their eccentricities (of which there were many) and their achievements.

Bruges evokes a sense of civilisation and peace – it takes an effort to realise that it has frequently been fought over, and the Western Front in the Great War was just up the road. Photo: W M Nixon

There’s no such thing as OTT in Bruges – some things are just even more normal than others. Photo: W M Nixon

It had been a sweet warm evening of early summer, but next day the rain eventually set in with Belgian thoroughness - probably the best conditions in which to see what’s left of the Western Front and its hundreds of cemeteries and memorial sites and former military installations, for I don’t think you could cope with it in bright sunny weather. But pleasant little houses and hamlets are everywhere - the gallant Belgians are determined to maintain normal life as much as possible after a war which displaced 600,000 of them from their homes, such that it was 1930 before life had returned to anything like normal, and all that with the next World War just nine years down the line…….

In Flanders Fields…..the former war zone in Belgium has hundreds of immaculately-maintained cemeteries. Every grave is kept to the same high standard, as no-one knows when some relative might call by, though many are the graves of soldiers “Known Only Unto God”. This happens to be the cemetery beside the Dressing Station where Canadian doctor John McCrae was based - he wrote one of the finest poems of the war, “In Flanders Fields”. Photo: W M Nixon

Our journey had extra specific purposes, as two of the group wished to plant poppied crosses at graves of relatives which the extraordinarily obliging staff had located in a sea of headstones,

Then like so many before us, we ended our tour at the Menen Gate in Ypres, Lutyen’s memorial masterpiece, for the Last Post at 2000 hours on Sunday evening.

In a human and civilising touch, the Last Post is now provided by the local Fire Brigade, as most of the military have moved on, while any remaining units are only on a short posting. For their part, the Ypres Fire Brigade make a very fine job of it. The first call of the bugles came through loud and clear, and then there was a pause while various groups laid wreaths with impressive natural dignity. There followed the second bugle call, resonating majestically in the acoustic perfection of the great arch. Then despite the large crowd, for a while it was so silent all you could hear was the steady fall of the rain. And birdsong. You get a lot of birdsong in Belgium.

The Menen Gate at Ypres – the little town was obliterated in the Great War, but when the inhabitants were finally able to return, they insisted on re-building it exactly as it had been before. Photo: W M Nixon

The captains and the kings and their many soldiers have all now gone – and in their absence, the Ypres Fire Brigade does a very good job of sounding the Last Post at the Menen Gate every evening at 2000hrs. Photo: W M Nixon

Having been to Ypres and having seen so much that is utterly moving or numbing in the countryside about it, we wish them well, those who will be gathering at HMS Caroline in Belfast next Tuesday. It is painful to remember. But it is worse to forget.

And then perhaps, as we get used to HMS Caroline being a ship of interest to everyone in Ireland and indeed to people throughout Europe and beyond, would it be too much to hope that she could become the centerpiece of a proper maritime museum? For although the Ulster Folk & Transport Museum along the coast at Cultra do have a small collection of boats of Irish interest, some are kept in store and not displayed at all, while others aren’t looking too happy amidst a maze of agricultural artefacts. Surely a port like Belfast could provide them with a proper home?