Displaying items by tag: Naomh Cronan

Dubliner Paul Keogh Receives Top Trophy For His Dedication to Promoting Traditional Gaff Rig

For many years until her transfer to Galway in 2021, the Clondalkin community-built Galway Hooker Naomh Cronan was a feature of sailing life in Dublin’s River Liffey at Poolbeg Y&BC in Ringsend, and she was a regular attendee at traditional and classic boat events throughout the Irish Sea and further afield.

Maintaining both her seaworthiness and the high level of activity which was central to her successful existence involved many people, but the one man who became known as “The Keeper of the Show on the Road” was Paul Keogh, who was her Sailing Manager for eighteen years after joining the building team which brought her construction to completion.

The result of a remarkable community effort – the Clondalkin-built Galway Hooker Naomh Cronan in Dublin Bay. Photo: W M Nixon

The result of a remarkable community effort – the Clondalkin-built Galway Hooker Naomh Cronan in Dublin Bay. Photo: W M Nixon

Paul’s quiet yet very determined enthusiasm, and his sometimes heroic patience as he ensured that Naomh Cronnan was always fully crewed - with newcomers being steadily recruited to the cause - was something for celebration. So when it came to a close in the summer of 2021 with the Cronan’s satisfactory transfer to Galway City custodianship, his fellow members of the Dublin Bay Old Gaffers Association began preparing a proposal that Paul’s unique contribution should receive the ultimate recognition, the Jolie Brise Trophy, which is the supreme award of their central organisation, the Old Gaffers Association.

She really is breath-taking – the magnificent Jolie Brise making knots

She really is breath-taking – the magnificent Jolie Brise making knots

The award was confirmed in the online and partly active Annual General Meeting of the OGA in Newcastle in northeast England at the weekend, and will be followed by a further presentation in Dublin in due course. Meanwhile, it is timely to note that in celebrating Paul Keogh’s achievement, we are also celebrating what is arguably the greatest working gaff cutter ever built, the 56ft 1913-vintage Le Havre pilot cutter Jolie Brise. She served only briefly on pilot duties before being superseded by powered vessels, but since then has gone in to an unrivalled career as an offshore racer – she won three Fastnet Races – and sail training vessel.

An impression of latent power – Jolie Brise in Belfast Lough in 2015, on her way to being overall winner of that season’s Tall Ships Races. Photo: W M Nixon

An impression of latent power – Jolie Brise in Belfast Lough in 2015, on her way to being overall winner of that season’s Tall Ships Races. Photo: W M Nixon

Jolie Brise is a frequent visitor to Ireland, a notable occasion being in 2015 when she was in Belfast Lough during that year’s programme of Tall Ships Race, in which she excelled herself by being winner of both her class and the overall fleet when the series concluded. She is a magnificent vessel which never fails to excite admiration, and young Tom Cunliffe - the John Arlott of English sailing – captures it well in this enthusiastic video

Christmas Dreams Of Irish Wooden Boats – Old & New, Real & Fantasy

The season is upon us for goodwill and dreams of very special gifts. And for many Irish sailors, the dream Christmas present would be an elegantly classic or solidly traditional wooden boat, with all maintenance and running costs somehow covered by Divine Providence into infinity……W M Nixon goes down the Yuletide timber trail.

Love of wood is part of what we are. It’s in our genes. At some times and some places in the remote past, an instinctive fondness for wood, and an inherited ability to do something useful with it, would make all the difference between survival and extinction. So though today the availability of other more purposeful materials may have transformed boat-building, a new boat without some sort of wood trim is a very rare thing indeed.

At a more personal level, many of today’s generation of sailors cherish family memories of the communal building of wooden DIY kit boats at home. Here, there and everywhere, a drawing room or little-used dining room found itself a useful new purpose as a boat-building salon, with Mirror dinghies and occasionally larger craft taking shape in domestic settings throughout the land.

“Our daddy the boat-builder” became a household name in his own household. And for those who sometimes wonder why today’s adult sailors can become misty-eyed at the very thought of the Mirror dinghy (which really was and is a wonderful design and concept), the answer surely is that at a significant stage of their sailing and family life, a Mirror dinghy was centre stage, the symbol of a family’s shared values, hopes and interests.

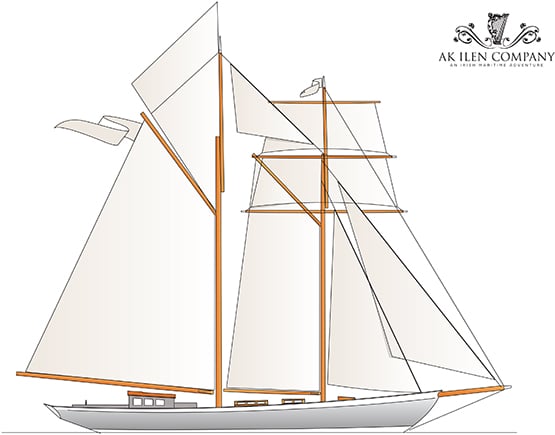

But maybe the most important thing about the Mirror is that she is so eminently practical. So perhaps at Christmas we should allow our imaginations to take flight and soar high to envisage the complete wooden dreamship. And there she is as our header image, introducing this week’s meandering thoughts. That schooner at the moment is total fantasy. But any sailing enthusiast who looks at that concept design and doesn’t think: “Now there’s my dreamship”, well, he or she just doesn’t have a true sailing soul.

The origins of Eirinn, as she is named for the time being, go back to 2012, when the nascent Atlantic Youth Trust sought suggestions as to what a new sail training vessel for all Ireland should look like. But with their proposals recently getting the first real hints of a fair wind from both governments, the AYT have gone firmly down the route of a 40 metre steel barquentine.

The Ilen as she was in the Spring of 2015 in Oldcourt...

….while in the Ilen Boatbuilding School in Limerick, spars and deckhouses were taking shape

….while in the Ilen Boatbuilding School in Limerick, spars and deckhouses were taking shape

Deckhouses built in Limerick are offered up on the Ilen in Oldcourt

However, down in Limerick where they were busy with moving forward the restoration of the Conor O’Brien 1926 ketch Ilen at two sites – the hull with Liam Hegarty in Oldcourt near Baltimore in West Cork, and the deckhouses, spars and other smaller items being built at the Ilen Boat Building School in Limerick – they gave some thought in 2012 to the possible form of a new sail training vessel. They came up with the concept of a classic 70ft schooner which they knew, thanks to the work on Ilen, that they could build themselves using the skills learned and deployed in re-building the O’Brien ketch.

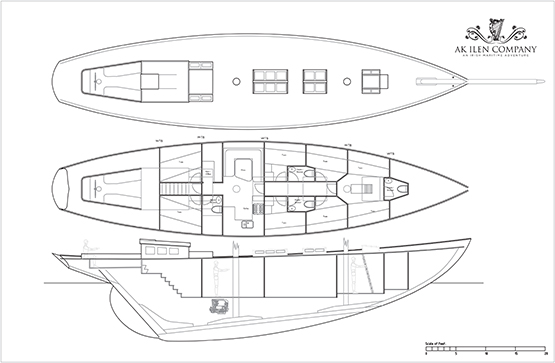

A classic hull for a classic schooner – Theo Rye’s profile and general arrangements plan for the schooner concept of 2012

But with the Ilen project moving steadily on towards the vessel’s commissioning next summer, and with other directly-related new proposals at an advanced stage in the pipeline, that sublime schooner concept is in a sort of limbo, truly a fantasy.

Yet she’s such a lovely thing that we’re happy to use her as our symbol of Christmas cheer. Her creators are Gary MacMahon of the Ilen Boatbuilding School, and Theo Rye, who is best known as a technical consultant in naval architecture, and on clarifying matters of design history and detail in boat and yacht design. But he can turn his hand to all sorts of design commissions if required. He came up with the clever concept for the CityOne dinghies in Limerick, and when Gary started musing about a classic training schooner, within the scope of what the Ilen school could do, as their answer to the AYT sail training vessel query, Theo came up with the goods and then some.

In fact, the design of the hull is so perfect that we’ll run it again right here to save you the trouble of scrolling back to the top. The overhangs at bow and stern are in harmony, but it is the sheerline which is the master-stroke. There isn’t anything you’d want to change in it, yet when you look at other famous schooners such as the fictional Southseaman (in real life she was Northern Light) in Weston Martyr’s masterpiece of maritime literature The Southseaman – the Story of a Schooner (1926), we see a sheerline which is too flat in the way of the foremast. But with Eirinn, the curve is just right, and it’s something achieved by tiny adjustments and balances which the eye can’t really perceive, yet somehow it registers the sublime harmony of the total concept.

Worth a second look – and then a third one. The longer you look at the lines of Eirinn, the sweeter they seem. But her overall appearance might be improved with a slight rake of the masts

A schooner sheer not quite right – Weston Martyr’s Southseaman (aka Northern Light) could have done with a livelier sheerline abeam of the foremast.

A schooner sheer not quite right – Weston Martyr’s Southseaman (aka Northern Light) could have done with a livelier sheerline abeam of the foremast.

So Theo Rye not only writes critiques of other people’s designs, but if given the chance he can personally come up with something which is wellnigh impossible to fault. Of course, we mightn’t quite go for the same rig – a little bit of rake in the masts wouldn’t go amiss - and for private use you’d want something a little different from the dormitory layout of the training ship. But that said, this is a beautiful yet not excessively pretty-pretty hull, a boat which sings. And the fact that she’s beyond just about every private owner’s reach only adds to the mystique.

But to redress the balance, last week we’d an inspiring evening’s entertainment and information about a dreamship which really is being re-created. It was the December gathering of the Dublin Bay Old Gaffers Association in the ever-hospitable Poolbeg Y & BC, and a full house was there to hear about how Paddy Murphy of Renvyle in the far northwest of Connemara is getting on with his mission of bringing the famous Manx sailing nobby Aigh Vie back to life.

Paddy himself is something special. When asked his trade, he says he’s a blacksmith. But he can turn his hand to anything. Originally a Dub, his early sailing experiences included owning a Flying Fifteen and a Dragon, though not – so far as I know – at the same time. But then got the gaff rig traditional boat bug, and a sail on Mick Hunt’s Manx nobby Vervine Blossom sent him in pursuit of near-sister Aigh Vie. She was reportedly for sale, having for a long time been the pet family cruising boat of Billy Smyth and his family at Whiterock Boatyard on Strangford Lough, after spending her final working years fishing as a motorized vessel out of Ardglass.

Aigh Vie as she was in Whiterock Boatyard when Paddy Murphy bought her, her elegant huul shape clearly in evidence

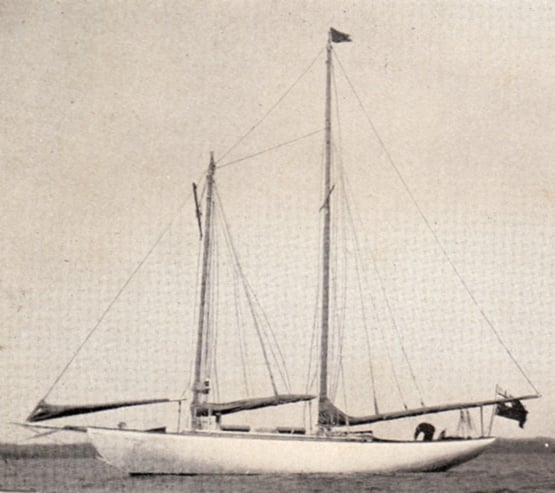

Aigh Vie in her final working days as a motorised fishing boat based at Ardglass

Aigh Vie in her final working days as a motorised fishing boat based at Ardglass

The deal was done, an ideal buy for a special man like Paddy Murphy, for the Aigh Vie is one very special vessel. The Manx fishing nobbies reached their ultimate state of development in the first twenty years of the 20th Century before steam power and then diesel engines took over. The nobby evolved to an almost yacht-like form through vessels like the 43ft White Heather (1904), which is owned and sailed under original-style dipping lug rig by Mike Clark in the Isle of Man, and the 1910 Vervine Blossom, now based in Kinvara, which was restored by Mick Hunt of Howth, but he gave her a more easily-handled gaff ketch rig which looked very well indeed when she sailed in the Vigo to Dublin Tall Ships Race in 1998.

It was a sail on Mick Hunt’s 1910-built Manx nobby Vervine Blossom which inspired Paddy Murphy to go in pursuit of Aigh Vie

It takes quite something to outdo the provenance of these two fine vessels, but the story of Aigh Vie (it means a sort of mix of “good luck” and “fair winds” in Manx) is astonishing. It goes back to the sinking of the Lusitania by a German U Boat off the Cork coast in May 1915, when the first boat to mount a rescue was the Manx fishing ketch Wanderer from Peel, her crew of seven skippered by the 58-year-old William Ball.

They came upon a scene of developing carnage. Yet somehow, the little Wanderer managed to haul aboard and find space for 160 survivors, and provide them with succour and shelter as they made for port. In due course, as the enormity of the incident became clear, the achievement of the Wanderer’s crew was to be recognised with a special medal presentation. And then William Ball, who had been an employee of the Wanderer’s owner, received word that funds had been lodged with a lawyer in Peel on behalf of one of the American survivors he’d rescued. The money was to be used to underwrite the building of his own fishing boat, to be built in Peel to his personal specifications. The name of the donor has never been revealed, but the result was William Ball’s dreamship, the Aigh Vie, launched in December 1916 and first registered for fishing in January 1917.

Over the years, the Aigh Vie became a much-loved feature of the Irish Sea fishing fleet. Tim Magennis, former President of the Dublin Bay Old Gaffers Association, well remembers her from his boyhood days in the fishing port of Ardglass on the County Down coast. Her working days over, Billy Smyth gradually converted her to a Bermudan-rigged cruising ketch with a sheltering wheelhouse which enabled the Smyth family to make some notable cruises whatever the weather. His son Kenny Smyth, who now runs the boatyard with his brothers and is himself an ace helm in the local 29ft River Class, recalls that the seafaring Smyth family thought nothing of taking the Aigh Vie to the Orkneys at a time when the average Strangford Lough cruiser thought Tobermory the limit of reasonable ambitions.

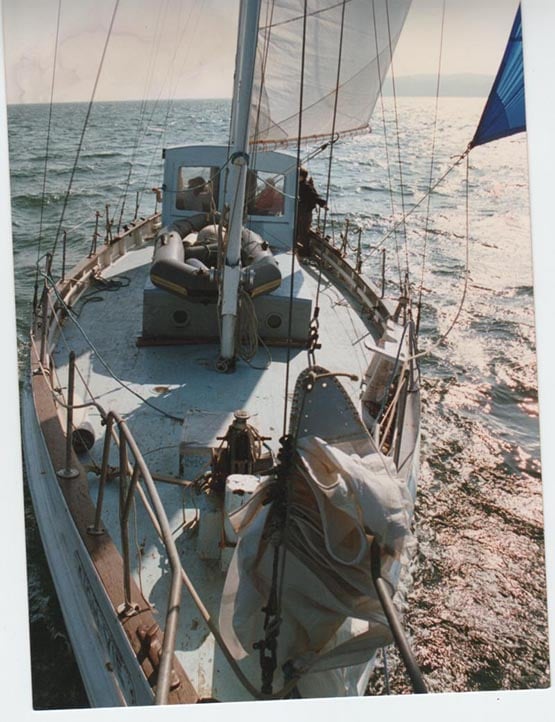

After he’d bought the Aigh Vie and brought to her first base in Howth, Paddy Murphy soon realised he’d still a lot to learn about sailing and about keeping hard-worked old wooden boats in seafaring condition. But he’s such an entertaining and inspirational speaker that you’re swept along in his enthusiasm and empathise with his admission that, now and again, he felt things were getting on top of him.

Sisters - Vervine Blossom (foreground) and Aigh Vie in Howth

Sailing days on the Aigh Vie from Howth, before it was decided that she needed a major restoration

Following several seasons with increasing evidence of problems, he decided that a virtual re-build was necessary. It was then that the Dublin wooden boat owners’ perennial problem shot to the top of the agenda. In our very expensive city, the space and shelter to work long hours at an old wooden boats is almost impossible to come by, and he’d to shift the big Aigh Vie several times. On one occasion, he was asked to move in a hurry out of an ESB shed, but was offered £1,000 (this was pre-Euro days) to do so. He moved heaven and earth and finally found somewhere else at considerable expense, got the Aigh Vie installed there, and then went back to collect his thousand snots. Only to be laughed at. The manager told him it was the only way he could see to get the old boat moved out, but there were absolutely no funds available at all for such a thing, and surely Paddy would have guessed that?

The re-building under way at Renvyle, using the technique where hull shape is retained by first replacing every other frame

With one thing and another, he moved to Renvyle in Connemara where he liked the big country and the open spaces and the friendly people right on the edge of the Atlantic, and in time Aigh Vie came too, and found herself being slowly re-born under a special roof. But it was demanding work for one man, so every so often a team led by Paul Keogh of the famous Galway Hooker from Clondalkin, the Naomh Cronan, together with a good selection of DBOGA specialist talent, descends on Renvyle to put in a ferocious day or two of work, and then on the Saturday night they put a fair bit of business the way of the pub at Tullycross.

The planking was more easily restored by laying the Aigh Vie over on her side

Agh Vie upright again, and the deckhouses are being put in place

Old Gaffers Association International President Sean Walsh (right) and Peter Redmond install Aigh Vie’s new Perkins diesel. Photo: Cormac Lowth

One of the options for Aig Vie’s rig is the classic lug ketch as shown here with Mike Clark’s 1903-built White Heather

So now, many years later, the journey towards the restored Aigh Vie is getting near its destination. But it will never be fully ended. Thanks to sails, spars and rigs donated from other boats, Paddy has the choice of either gaff ketch or classic lug rig, so she’ll always be work in progress. Which is good news. Because every couple of years or so, the DBOGA can guarantee a full house to hear Paddy Murphy talking about how the Aigh Vie story is going.

He’s a wonderful speaker, sometimes almost messianic, and he shares his every feeling. Thus he mentioned that one day he was feeling a bit low, and he just went out to look at the big boat down by the shore, seeking some sort of inspiration. His mind had been elsewhere with the details of completing the interior, but he suddenly realised that he was at the stage of thinking of putting the white paint on the topsides. So he just set to with a big paint brush and a bigger tin of paint, and Aigh Vie was transformed. So was he. “That’s the secret” says he. “If you’re feeling a bit down, just go out and slap on some white paint. It works wonders.”

Feeling a bit down? Then just go out and slap a coat of white paint on the boat – it works wonders