Displaying items by tag: round the world

'Use It Again!' Trimaran Departs From Lorient on Round the World Upside Down Record

Romain Pilliard and Alex Pella set off on Tuesday January 4, 2022 on the Round the World Record Upside Down. The trimaran Use It Again !, the former Ellen MacArthur boat, crossed the starting line at 17 hours 36 minutes and 04 seconds between the Pen Men lighthouse on the Isle of Groix and the Kerroc'h lighthouse in Lorient. This Round the World Tour against the prevailing winds and currents has never been successful in a multihull, a real sporting challenge for Romain Pilliard and Alex Pella.

In a north-north-west flow of around twenty knots, at sunset, the bows of the trimaran Use It Again. crossed the starting line at 17 hours 36 minutes 04 seconds between the Pen Men lighthouse on the Ile de Groix and the Kerroc'h lighthouse in the east of Lorient.

In front of Romain Pilliard and Alex Pella, a 21,600-mile round-the-world tour on a direct route but nearly 30,000 miles in reality. During more than a hundred days of racing, the Franco-Spanish duo are determined to show concretely that it is possible to think about performance and to live exceptional adventures while minimizing its impact on the planet.

* Eighteen hours after the start, the Trimaran Use It Again! is progressing at 12 knots in the Bay of Biscay at the latitude of Bordeaux. As expected, Romain and Alex had to deal with a weaker southerly wind during the night but should touch up a stronger northwesterly flow during the day to get around the Spanish tip.

"It shakes this morning, the sea is rough. We reduced the sails to preserve the boat. "explained Alex Pella this morning.

"They had a rough night with a few grains and fired as expected in soft around 7:30 this morning. Everything is fine on board, for the time being they are faster than the initial routing". said Christian Dumard, shore-based router.

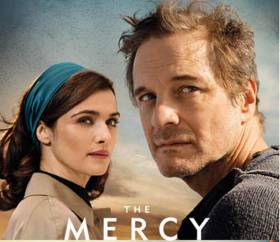

All Sailors Will Enjoy 'The Mercy' Sailing Movie, Says Pete Hogan

Dublin artist and round–the–world solo sailor Pete Hogan reviews The Mercy, the sailing movie starring Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz that is to be released in Ireland on Friday.

I was invited to the premier of this movie in the Lighthouse cinema in Dublin.

Many sailors will be familiar with the famous case of Donald Crowhurst, the tragic participant in the original Golden Globe race organised by The Sunday Times in 1968 and which Robin Knox Johnston won and thereby made his name.

Crowhurst, having first faked his progress in the race, is generally accepted to have killed himself by jumping overboard. It is a story which refuses to go away having inspired several books, documentaries, plays, poetry and now a reasonably big budget movie. Almost like the Flying Dutchman, the search for Franklin or the tale of Ulysses it has seeped into the lore of the sea.

The movie, starring Colin Firth and Rachel Weisz is a well-constructed affair. The nautical detail is good and includes the construction of an accurate replica of the 40’ tri he used in the race. It’s a lot better than many depictions of nautical matters by Hollywood. The movie follows closely the accepted narrative described in the original book by Tomlinson and Hall published in 1970. (The Strange Last Voyage of Donald Crowhurst). There is little doubt as to the facts of the tragedy. Crowhurst purposely and pointedly left all his writings and charts for others to find - like a lengthy, gruesome suicide note.

The period detail is well done except for the corny London Boat show. It well illustrates the difference between yottin then and now. The hack journalist who promotes Crowhurst almost steals the show. Crowhurst comes across as a model, well adjusted, family man with a beautiful wife and three adorable cute children. Consequently it is less easy to explain how it all went so horribly wrong. Colin Firth makes a good attempt at portraying the mental disintegration of the lone sailor as pressure mounts and failure becomes more apparently inevitable. The boat looks appropriately shambolic and weathers well as the voyage progresses. Firth looks a bit too handsome towards the end rather than the demented tragic figure he must have been. When he hacks at his hair with a nautical knife he looks as if he has just visited Peter Mark.

Calm beautiful wife Rachel Weisz, does most to explain what went wrong. As she slams the door on the baying pack of media reporters, she declares ‘ You are all to blame, every one of you. You pushed him overboard’.

Happily we are spared the actual sight of Crowhurst’s end. Instead we follow into the depths his chronometer which he is believed to have clutched as he jumped off the stern onto the astral plane. This is not really a date movie but it is a brave one in that there was never ever going to be a happy ending.

This is a movie which all sailors will enjoy, especially those who lived through those pioneering heady days of the early OSTAR races and the Sunday Times Golden Globe race of 1968.

Postcript

At the premiere reception I was introduced to Gregor McGuckin who intends to take part in this year’s Golden Globe Race which is being held to commemorate the original one in which Crowhurst took part 50 years ago. Like Donald Crowhurst, Gregor obviously has a dream. But he seems much better grounded, balanced and prepared. I wish him good luck.

Kinsale Sailing Couple Complete Round the World Voyage

Round the World Irish sailing couple Paraic O'Maolriada and Myra Reid returned to their home port of Kinsale in County Cork at the weekend having completed a six–year circumnavigation writes Bob Bateman.

The fluent Irish speakers returned to the West Cork port on Saturday in their 63–foot long yacht 'Saol Eile' to be greeted by family and friends. The craft was dressed with flags from all the countries they had visited over the course of their 43,000 nautical miles voyage.

Paraic, a non–swimmer, was formerly a master brewer in Guinness Brewery who has also designed breweries in Scotland. Paraic says it was a relatively quick decision to 'pack it all in' and take on the global journey.

Above and below: The 63–footer yacht Saol eile safely back in Kinsale after its round–the–world voyage. Photos: Bob Bateman

Above and below: The 63–footer yacht Saol eile safely back in Kinsale after its round–the–world voyage. Photos: Bob Bateman

The couple prepared for the journey in 2010 with assistance from Zafer Guray of Bantry who gave them tips about how to handle the boat with just the two of them onboard.

Married for 49–years, Paraic and Myra said their scariest moment of all came on day two when the short–handed couple encountered a force nine storm in the Bay of Biscay.

Their most pleasant cruising experience was in Namibia, sighting hundreds of thousands of birds pelicans and flamingos. Another place they loved was Madagascar with its multitude of beautiful anchorages. But Myra says overall that 'the best part of the trip was being home'.

Round the World Irish sailing couple Paraic O'Maolriada and Myra Reid reunited with family at Kinsale Yacht Club. Photo: Bob Bateman

Round the World Irish sailing couple Paraic O'Maolriada and Myra Reid reunited with family at Kinsale Yacht Club. Photo: Bob Bateman

British Powerboat Legend Launches Round the World Record Bid in Revolutionary Torpedo Eco-Boat

#powerboat – British ocean powerboat racing legend, Alan Priddy, will this week launch a £2.9 million round the world record bid in a new torpedo Eco-boat powered by a revolutionary fuel emulsion that slashes harmful emissions.

Mr Priddy hopes to shave up to seven days off the current powerboat record of 60 days 23 hours 49 minutes, held by New Zealander Pete Bethune. He will make the formal announcement at the Fathom Ship Efficiency Conference, in London on Wednesday, 1st October.

The boat will pierce the waves like a torpedo, rather than surfing them, with its super-efficient design, a variant of the "fast displacement hull". This reduces fuel consumption by up to 30 per cent, and should also make the 24,000 mile trip smoother than a voyage in a conventional hulled boat.

Inside the boat will be the latest radar, safety and communications equipment from Raymarine and Iridium Communications.

The vessel will be powered by a revolutionary fuel emulsion, a mixture of diesel, water and emulsifier, which when burnt reduces harmful emissions such as particulate matter and Nitrous Oxides.

The British company behind the emulsion, SulNOx Fuel Fusions, claim that they have cracked the problem of stratification that has blighted this technology in the past. They say that by smashing ordinary fuel and water together repeatedly and under great pressure they can alter the size of the fuel particles at a nano level. To further stabilise this mixture an emulsifying agent is added. This they say has created the first safe, reliable and cost-effective fuel emulsion which will be used to power the boat as part of a million pound deal.

The effects of the emulsified fuel on the engines and the emissions will be monitored for the duration of the voyage and the results published online.

Mr Priddy commented: "This project is the culmination of a lifetime's work that I hope will highlight the amazing qualities and skills that we have in abundance in our country - the best sailors, engineers, boat builders and designers. This is why when we started this project six years ago, we called ourselves Team Britannia.

"Given last week's referendum that saw the real prospect of our country being broken up, this name seems all the more appropriate today. I hope it serves as reminder of what this country has and can still achieve."

The Team hopes to start building the boat early next year and set off on the historic voyage in November 2015, when the weather conditions will be just right.

The 80ft vessel, built out of marine grade aluminium, will be launched in late spring to allow it to complete its sea trials. It has not been named yet, but Mr Priddy says they are in talks with potential sponsors about this and hope to make an announcement in the New Year.

Mr Priddy continued: "Our first attempt at building a boat came to an abrupt end in 2012 when a fire at an adjoining factory damaged the structural integrity of the hull - but we learnt from this setback, thanks to Professor Cripps' improved design. With the addition of SulNOx, we have a boat that will not just break the world record, but will do it cleaner and greener than anyone else."

To complete the record attempt the boat must pass through the Suez and Panama Canals, cross the Tropic of Cancer and the Equator, and start and finish in the same place. The world record authorities UIM (Union Internationale Motonautique) have approved Team Britannia's proposed route, which will start in Gibraltar and call at Puerto Rico, Acapulco, Honolulu, Guam, Singapore, Oman and Malta to take on fuel.

The boat will be crewed by a team of eight, including Mr Priddy and his second in command Dr Jan Falkowski, who will be responsible for the physical and mental health of the crew.

Mr Priddy also hopes to offer a place on each leg of the epic voyage to injured servicemen or women from the Royal British Legion, or service charity BLESMA (British Limbless Ex-Serviceman Association).

He concluded: "We have the finest maritime designers, builders and sailors in the world. The British boat Cable & Wireless Adventurer first set the round the world powerboat record in 1998 and held it for nearly a decade. When this record, the pinnacle of powerboating was lost to the New Zealand boat Earthrace, I knew we had an amazing opportunity to once again showcase the best of British. To show why our marine industry is still the best.

"Team Britannia aims to do just that. It brings together just a few of the people who make Britain and our marine sector great."

Irish Trad Boat Leader is Veteran of Gaffer Global Circuit

#vintage boats – The season-long Golden Jubilee cruise of the Old Gaffers Association starts to roll this weekend, with vintage boats from the Thames Estuary setting out tomorrow to rendezvous in the Orwell estuary in Suffolk with character boats already on their way from Holland. And when the growing fleet reaches Dublin Bay for major events between May 31st and June 4th, they'll find the welcoming party is headed by a sailor who has been round the world under gaff rig.

The Old Gaffers Association was barely a year old when the current President of the Dublin Bay branch set out on a global circumnavigation under traditional rig in an already famous classic ketch, a vessel whose status was to become almost legendary when this voyage was completed.

It was the morning of Sunday 21st February 1965 when the 47ft Sandefjord slipped her lines from a quayside packed with friends and well-wishers in Durban, South Africa, and headed seaward down the harbour with an accompanying fleet. Instantly into open ocean at the pierheads, she was soon heading west for Cape Town, reeling off the miles on a close reach as her goodwill flotilla peeled off one by one to head back to the shelter of the great port. Sandefjord was now alone on the high seas

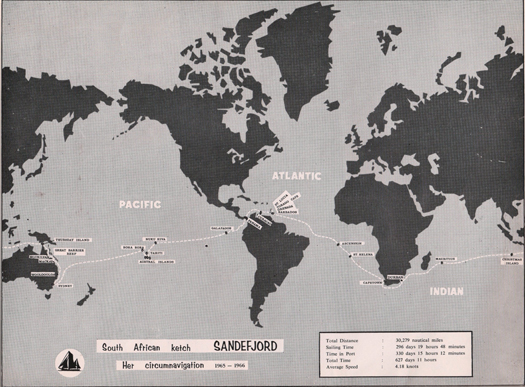

But the friends and supporters were to be out there again in increased numbers two years later to greet her when she returned from the eastward, with 30,729 miles completed in a classic global circumnavigation which had gone on from Cape Town through the South Atlantic to the Caribbean, thence to the Panama Canal and on to the Galapagos, then on across the wide blue waters of the Pacific to Polynesia and eventually to Sydney in Australia. From there it was northwards, cruising through the Great Barrier Reef and on into the Indian Ocean, then southwestward on the final long transoceanic leg, back to a rapturous welcome in Durban.

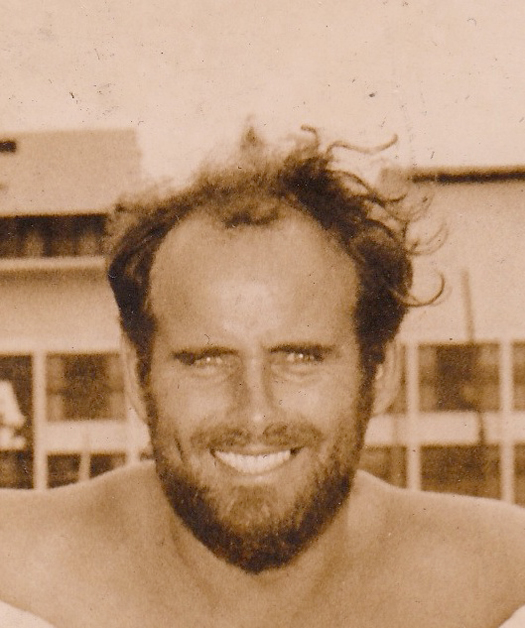

Tim Magennis in 1965 after he'd joined Sandefjord's crew

It is Tim Magennis, longtime member of the Dublin Bay OGA and its current President, who gives us the direct link to this fine voyage. With a boyhood in the coastal village of Ardglass in County Down, most of his early seagoing experience was with summer jaunts on one of the local fishing boats. But having shown a youthful a talent for journalism, he went straight into it from school, soon finding his way to national newspapers in Dublin.

From there, he went on to work in newspapers in Africa in the late 1950s, and by the early 1960s found himself on the staff of the largest daily in Durban. Always drawn to the sea, he was fascinated by Durban's port, the largest in South Africa. Yet despite its size he noted that his paper gave port matters no prominence whatever. When he pointed this out to the editor, Tim was promptly detailed off to write a regular column about maritime affairs. Hanging out on the waterfront became part of his job.

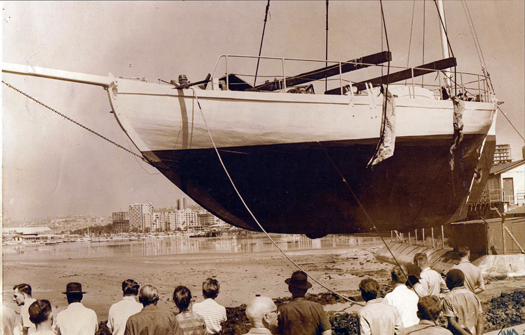

Sandefjord being craned in after her restoration in 1964-65

Through this, he met up with the people restoring Sandefjord, a classic former Redningskoite designed by Colin Archer (1832-1921), Number 28 constructed in 1913 by Jens Olson at Risor Batbyggeri. She was one of the last of the type specifically for rescue work to be built to the designs of the famous Scottish-descended Norwegian naval architect, who had also designed and built Erskine and Molly Childers Asgard in 1905. Although motor-powered lifeboats had been about since G L Watson pioneered the first one for the RNLI in 1904, sail and oar continued to play a prominent role in many rescue services, and the exclusively sail-powered Sandefjord accompanied the Norwegian fishing fleet from 1913 to 1934.

Stood down from rescue duties after 21 years of gallant service, in 1935 she was bought by noted Norwegian ocean voyager Erling Tambs, who wanted to provide a Norwegian presence in the forthcoming Transatlantic Race from Newport, RI to Bergen. Crossing the Atlantic westward in May 1935, Sandefjord was pitch-poled with the loss of one crewmember. But Tambs and his remaining shipmates still managed to nurse her to Newport, where they sorted the damage, and then raced back across the Atlantic.

In 1939, with World War II imminent, Tambs sailed her out to South Africa, where she was sold to Tilly Penso of the Royal Cape YC, who kept her with loving care for twenty years. She became a cherished part of the Cape Town sailing scene, with her rig simplified for family sailing by conversion to Bermudan ketch.

With Tilly Penso's death in 1959, she was sold by his estate, and went through a quick succession of owners. Though her gaff rig was restored, she was slowly going downhill, and by 1962 was more or less abandoned in Durban. There, already on the slide to becoming a rotting hulk, she was spotted by a restless young South African of Irish descent, Patrick Cullen (23), who despite having a very young family, had notions of a seagoing adventure. His brother Barry (24) was a qualified master mariner, and the two of them saw the potential in Sandefjord.

Slipping the lines - departure from the Durban quayside

The notion of a two year voyage round the world to the romantic South Seas took shape, with a proper film being made of it to make their fortunes afterwards. They managed to buy Sandefjord with the support of their mother in 1963, and secured a place on the Durban waterfront for a restoration project which soon became almost a re-build. But these were two very determined young men, and soon they were attracting like-minded spirits to join their project. It was all done in a very businesslike way, with crewmembers being required to sign a clearcut contract and commit one thousand rands up front towards the expenses of the voyage.

It was in those heady days of hard preparatory work and boundless horizons that the recently-appointed Durban maritime correspondent met up with them. At 32, Tim Magennis may have been a few years older than the next oldest member of Sandefjord's crew, but he always seemed much younger than his years - he still does at 81 – and within days he was being swept up with shared enthusiasm. He jacked in his dream job, though agreeing to file reports from around the world and write up the story for the paper on their return, and signed on as the final member of Sandfjord's crew of six, throwing himself into the final frantic months of preparing the ship for the great voyage.

Getting under way from Durban

The departure from Cape Town had a fleet of well-wishers which included two boats of the Royal Cape OD class (see Sailing on Saturday 02/02/13)

It was a classic cruise, all the better for being at a time before sailing became overly regulated and monitored. Thus although they'd a painfully slow passage from Panama out to the Galapagos, at one stage taking an entire week to make good one hundred miles, once they got to those extraordinary islands they were able to cruise among them with a freedom denied in today's heavily regulated environmental protection of that unique place.

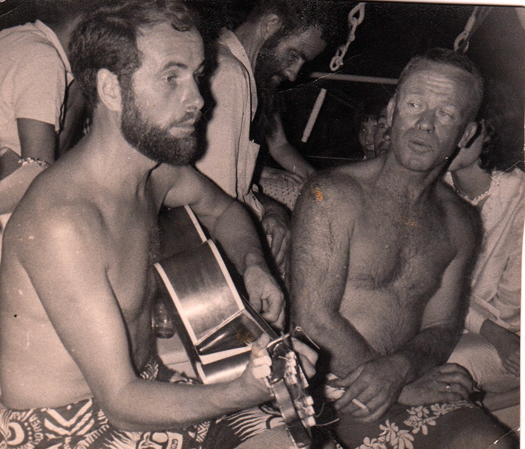

The President of the DBOGA in his days as an ocean busker – Tim Magennis with his guitar in the South Seas aboard Sandefjord.

Tahiti was still a place of romance before mass tourism made it blasé, and among the Pacific islands Tim's talents with the guitar were much in demand. But they surely paid for their lotus eating in the South Seas. The passage on to Sydney, far from being tradewind bliss in southeasterlies, became a slog almost all the way against unseasonal headwinds which culminated in yet another gale on the final night at sea. It brought down the mizzen mast around their ears, and there was a fierce struggle to secure the broken spar on deck.

Bowsprit work in the open ocean

So who needs Europe? Sandefjord's circumnavigation of 1965-67

Sandefjord living the South Seas dream

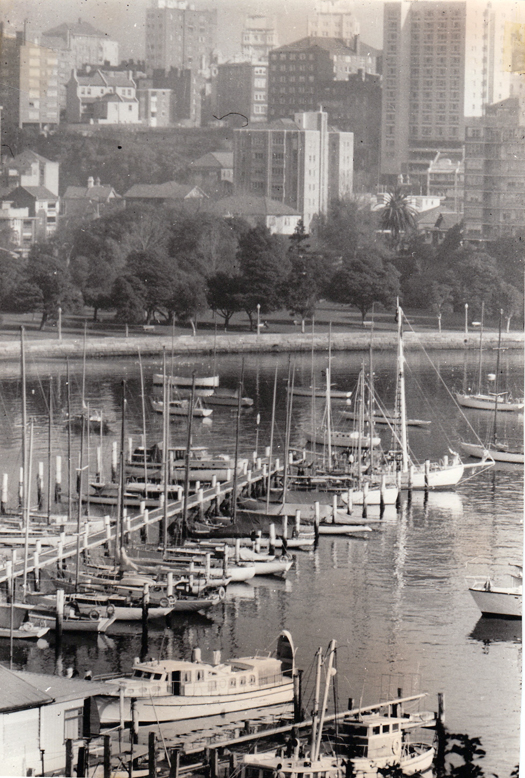

But when they finally arrived exhausted and battered at the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia in Rushcutters Bay, they'd come to the right place. After taking 50 days for a passage which should have taken only about 33, with stores down to just 20 cans of baked beans, they were distinctly peckish. However, lunch on arrival at the CYCA was just the job, with enormous steaks. Tim is slim now, as he was then. Yet like the rest of the crew, having enjoyed one enormous Australian lunch, he simply sat on and ate his way right through a second one, with all the trimmings.

Urban paradise – the CYCA provided a haven for recuperation and repair in Sydney, with Sandefjord's mizzen re-rigged after breaking on the last night at sea

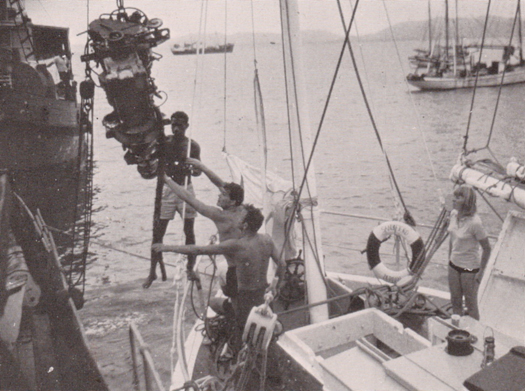

They gave a boat a complete refit at Sydney, glued and fastened the saved mizzen mast, and then headed on north for the Great Barrier reef. But inevitably at this final stage of the voyage, resources were becoming stretched, so when the gearbox on their Perkins diesel gave up the ghost, they sold the otherwise sound engine for 400 much-needed Australian dollars at Thursday Island and completed the rest of the voyage, along the north coast of Australia, across the Indian Ocean and home, under sail only.

A little bit of fund-raising with the sale of the engine at Thursday Island

Their average speed for the entire cruise was 4.18 knots, but when you see the one hour and 54 minute film – which has recently been re-mastered and is well worth viewing for this glimpse of life when the world was a simpler place – you soon realize that with half a decent breeze, the handsome Sandefjord could trot along in some style. And for her young crew, it was simply the time of their lives.

The triumphant return. Her sails may be showing evidence of hard work, but Sandfjord arrived back in Durban in fine shape.

Back in Durban, reality intervened. Tim found himself locked into a hotel room until he completed the account of the voyage for his newspaper. Then a message from home from an older brother, an officer in the Irish army, was a three line whip – he was to get back to Ireland soonest for their parents' Golden Wedding anniversary.

He returned to an Ireland considerably changed. In the late 1960s, the place was finding new and very welcome vitality. He never returned to Durban, but married Ann and settled in Dun Laoghaire on the shores of Dublin Bay, perfectly fitting his new job as PR for the Irish Tourist Board. He became a voice for Ireland. You could always be sure that the usually gruff William Hardcastle of the BBC's World at One would have a smile in his voice after chatting on the air with Tim Magennis about something of interest in Ireland.

As for Sandefjord, Patrick Cullen sailed her with his family in the Cape Town to Rio Race of 1971, and then cruised north through the Caribbean to New York and on to Mystic Seaport in Connecticut, where she was based from 1972 to 1976. She was sold there by Patrick and Barry in 1976 to Erling Brunborg, who sailed her home to Norway.

Brunborg, a stalwart of the Colin Archer world, eventually sold her in 1983 to Petter Omtvedt, who in turn spent ten years on a massive re-build, making her exactly as she'd been as a Redningskoite. When this was completed, she was bought in 1993 by Gunn von Trepka who – with her husband Alan Baker – has completed many Tall Ship Races in European waters as family sailing ventures. And as this year is Sandefjord's Centenary, there'll be a mighty party in Risor at the end of August which hopefully will be attended by all the surviving members of Sandefjord circumnavigating crew, though sadly Pat Cullen, who had the first spark of the idea of the world voyage, died some years ago.

The Centenarian – Tim Magennis aboard the restored Sandefjord in Risor in Norway, where she will celebrate her hundredth birthday in August 2013

Needless to say, Tim Magennis will be in the heart of the Centenary party, the father of the crew. But meanwhile, he has much to attend to in Dublin. With retirement he has been able to focus even more strongly on his love of sailing and maritime heritage, and it was very right with the world when he was acclaimed as the new President of the Dublin Branch OGA in the Autumn of 2012, no better man with the Golden Jubilee Cruise arriving at the end of May.

Tim Magennis (left) seen recently at a DBOGA meeting with fellow gaffers Ian Malcolm and Sean Cullen

His own boat these days is the 25ft Marguerite, a lovely little clipper-bowed gaff sloop designed in 1896 by Herbert Boyd, who later designed the Howth 17s in 1898. A great friend and fellow owner of another vintage Boyd boat, the 26ft Eithne from 1893, is Patrick Cullen's son Sean, who is very much an Irish seafarer these days – he commands one of the national maritime survey vessels, a long way indeed from racing aboard Sandefjord from Cape Town to Rio as a very young seafarer in 1971.

Tim's seagoing interests are many. He sailed many miles offshore with Don Street of Glandore aboard Don's famous ocean-crossing Iolaire. And more recently, while sailing across the Bay of Biscay aboard the square rigger Jeanie Johnston on a pilgrimage with a difference to Santiago de Compostela, his mobile phone rang, and the connection lasted just long enough to tell him he'd become a grandfather for the first time.

That's the way it is with Tim Magennis. There's always something new on the horizon. And there's quite a past too, for this is a man who once upon a time sailed right round the world on a fine gaff ketch when all the world was young, and everything was possible. So when the world of gaff rig comes to Dublin Bay in six weeks time, there'll be someone there to welcome them, a man who really does know what seafaring under gaff rig is all about.

They will be taking part in the eighth edition of the race that was founded by Sir Robin Knox-Johnston to give people from all walks of life the chance to race around the world under sail. At 40,000 miles it is now the world's longest ocean race.

They will be flying in from as far afield as Singapore, Australia, Finland, the USA, Chile and across the UK for the much anticipated event. This is where the reality of their participation in the race truly begins to kick in... with a skipper in place, team strategies start to take shape, roles are assigned to the crew and, with just three months to go until the race start, the countdown is on.

Teen Solo Sailor Dismasted in Indian Ocean

Teen solo sailor Abby Sunderland has been located alive and well, but dismasted, in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Sunderland was dismasted in heavy weather 2,000 miles east of Madagascar and 2,000 miles west of Australia.

Communications were lost with the 16-year-old as she sailed in heavy weather on Thursday. Her EPIRB went off just hours after her parents last spoke to her from California. Sunderland's emergency signal sparked emergency callouts from Australia and the French island of Reunion, and she was located in the early hours of this morning by a chartered Airbus A330 that set off from Australia to search the area of the EPIRB this morning, arriving on site at first light.

Sunderland was attempting to wrest the title of youngest solo circumnavigator from Jessica Watson, who finished her round-the-world voyage in Sydney last month. The previous record holder was Sunderland's older brother.

The title of youngest circumnavigator has raised serious questions in recent years. A young Dutch sailor, whose parents were keen for her to challenge for the title, were prevented from letting her do so by a children's court in Holland.