#isora – Dickie Richardson of Holyhead, who died last month aged 89, played a key role in the Irish Sea Offshore Racing Association during the Golden Age of distance racing in the area during the 1970s. Yet although he was best known as one of the moving spirits in the formation of ISORA in 1971, there was much more to him than this.

He was a remarkable man with an extraordinary ability to turn his hand to anything. Professionally, he was a consultant anaesthetist with some of his most noted work being done in the cardiothoracic surgical unit at Broad Green Hospital in Liverpool when open heart surgery was being developed, an area in which he was much involved.

But as was made clear at his well-attended funeral in Bangor, North Wales, he was an engineer at heart, a man who loved making and doing. He derived deep satisfaction from building his own boats and understanding all the technical processes, whether it was laying up glassfibre, making aluminium castings, fabricating stainless steel fittings, or installing beautifully finished wooden lockers which usually incorporated some ingenious design features reflecting his long experience of sailing.

A Lancashire man through and through, somehow he brought the spirit of the sea into the heart of the Liverpool suburb of Eshe Road North where he and his doctor wife Elspeth lived and reared their three sons Angus, William and Michael in an eccentric household in which there always seemed to be a boat at some stage of construction filling the front garden.

While his increasing eminence in Liverpool's medical establishment meant that he had links to both the Royal Dee and Royal Mersey Yacht Clubs, his sailing heart on Merseyside was definitely with the homely Tranmere Sailing Club. He'd been one of the team of volunteers which built TSC's new clubhouse in the early 1960s, and there, after a day of working at boats whose craning-out he had gaffered in his own easy-going way at Tower Quay in Birkenhead, he could while the evening away in contented and productive chat about solving boat maintenance and management problems.

Invariably, he'd be filling the air with strong aromas from his favourite pipe which, when sailing, he made seaworthy in rough weather by having the tobacco so firmly tamped in place that he could safely invert the bowl when rain or spray threatened to extinguish the blessed glow.

It was during the working years in Liverpool that he had the greatest variety in his boats. His sailing was largely self-taught, having learned through cruising a small boat in short hops along the challenging North Wales and Anglesey coasts. Then as the family grew, he acquired the Albert Strange-designed 29ft yawl Emerald, built in North Wales in 1938. But he was also branching out into participation in offshore racing, and became a member of the RORC, taking part in an early Middle Sea Race aboard the innovative 40ft S & S sloop Deb, owned at that time by Solly Parker of North Wales. Subsequently she was owned by David Hague and re-named Dai Mouse III to be frequently raced in ISORA events, and these days she's famous as Sunstone, cruised worldwide by Tom and Vicky Jackson.

Some of the ISORA fleet during the period when Dickie Richardson chaired the organization during the 1970s. Included in this group sharing Howth Harbour with the fishing fleet in pre-marina days are Philip Watson & Kieran Jameson's J/24 Pathfinder II (third left), the famous S&S 40 Dai Mouse III which is now better known as Sunstone (centre left), and the McGruer 17-ton yawl Frenesi (centre right). Photo: W M Nixon

Some of the ISORA fleet during the period when Dickie Richardson chaired the organization during the 1970s. Included in this group sharing Howth Harbour with the fishing fleet in pre-marina days are Philip Watson & Kieran Jameson's J/24 Pathfinder II (third left), the famous S&S 40 Dai Mouse III which is now better known as Sunstone (centre left), and the McGruer 17-ton yawl Frenesi (centre right). Photo: W M Nixon

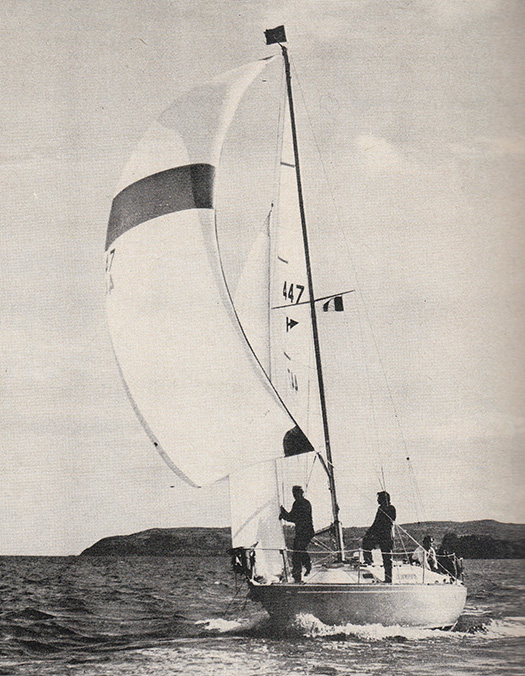

The Richardson's first boat with offshore racing ambitions was the Hustler 30 Skulmartin in 1971, which they finished from a bare hull. They were pioneers in the use of sails made by John McWilliam, who in those days operated under the Tasker label. Photo: W M Nixon

The Richardson's first boat with offshore racing ambitions was the Hustler 30 Skulmartin in 1971, which they finished from a bare hull. They were pioneers in the use of sails made by John McWilliam, who in those days operated under the Tasker label. Photo: W M Nixon

Dickie was to make his own first foray into being an offshore racing owner with the Hustler 30 Skulmartin, which he finished himself from a bare hull. That was his boat when ISORA was founded in 1971, but in late 1973 he bought the almost-new Billy Brown-designed Half Tonner Garland of Howth, which had won her class in the newly-inaugurated ISORA Captain's Cup Week in Holyhead, an event which in time developed into ISORA Week.

Dickie up-graded his new boat with a fractional rig, re-named her Blackwater in line with his policy of having boats named after navigation markers such as lightships in the Irish Sea, and took her in 1974 to the Half Ton Worlds in La Rochelle with a youthful Harold Cudmore as helmsman. In a large fleet they finished eight overall, but it was clear that new designs from Ron Holland and Doug Peterson were the future of offshore racing success. So Dickie and his teenaged sons acquired the bare hull of a Holland-designed Golden Shamrock from the builders in Cork, and finished her to become the Half Tonner Harry Furlong, named after a rock on the north coast of Anglesey.

Their former shipmate Harold Cudmore meanwhile was putting together his own Holland-designed Shamrock campaign with the intensely competitive Silver Shamrock, which duly won the Half Ton Worlds in Trieste in 1976, while back in the Irish Sea the hugely popular ISORA programme was to see Shamrocks in all their variations, Harry Furlong among them, featuring at the front end of the fleet.

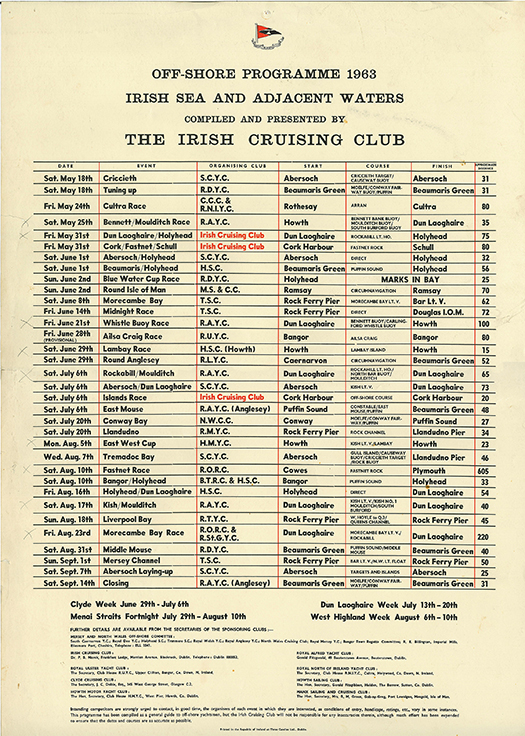

Until ISORA got itself up and running in 1971, all sorts of organisations were involved with distance racing in the Irish Sea. This is a programme issued by the Irish Cruising Club for the 1963 season.

Until Dickie Richardson with others like Hal Sisk from Dun Laoghaire launched the idea of an Irish Sea Offshore Racing Association after the end-of-season Pwllheli-Howth race in 1971, the offshore programme around the area had been fragmented, and date clashes were almost inevitable. Many organisations – some of them very informal - were involved, with the Irish Cruising Club and the Royal Alfred YC active on the Irish side, while in the north the Clyde Cruising Club interacted with the Belfast Lough clubs to run races across the North Channel. Over on the Welsh and English side, the Mersey & North Wales Joint Offshore Committee had developed into the Northwest Offshore Racing Association, and it was this body – with rapidly increasing numbers, particularly from the Irish side – which became ISORA in 1971 with its remit extending to include when possible events in the North Channel, and the annual Round Isle of Man Race, while also including an annual RORC event which might take the fleet to Cork.

What resulted was something which nowadays would be seen as an impossibly crowded and time-consuming programme. But it has to be remembered that times were very different during the 1970s. The Troubles were at their height, and links of friendship across the Irish Sea in a period of active terrorism could be difficult by any means other than a sailing boat. Thus the successful functioning of ISORA was definitely a power for the good, and at its height it had a remarkable fleet of 107 boats from all round the Irish Sea and adjacent areas taking part in its annual season-long championship. Its comprehensive programme, which guaranteed at least seven long weekends of sailing and racing afloat interspersed with friendship ashore in the ports visited, was exactly what people needed in those stressful times.

Inevitably, the challenges of running such an extraordinary and wide-ranging organization on an entirely voluntary basis were enormous, particularly as Dickie Richardson as chairman knew he had to do it with a minimum of fuss. This involved heroic restraint in diplomacy on his part, as normally he wasn't one to suffer fools gladly. Yet with the success of his efforts and those of his committee, for a while the clout of ISORA was such that they were able to hold impressive ISORA Weeks in Cork, Dublin Bay, Cardigan Bay off Abersoch and Pwllheli and even on the Clyde, thanks to their ability to bring a large fleet with them.

But it was all being done in a changing situation. An improved road network in England may have meant that owners from the big inland cities of the north could now reach their boats in Wales more easily, but for some of them an hour or two of extra travel meant they could access boats to race with the RORC fleet from the Solent, which provided modern facilities that far out-stripped the excessively tidal and very primitive harbours of North Wales, and the still-undeveloped ports on the Irish coast.

Then too, because the biennial ISORA Week mopped up all available fleets to one venue, other places felt left out and became more active in promoting their own regattas such as the Scottish Series on Loch Fyne. This clashed directly with the Irish Sea's Round the Isle of Man Race, and it was the latter which faded.

Perhaps most importantly of all, however, social attitudes were changing. The rough and ready approach of it being acceptable for dedicated offshore racing enthusiasts to disappear off for a very long weekend at least seven times a summer, often in order to race an event of barely a hundred miles, just didn't do in the modern family-oriented world.

This led to the introduction by individual clubs of longer events which featured a more clearly defined timescale, with the first biennial Round Ireland Race from Wicklow in 1980, while the National YC's Dun Laoghaire to Dingle Race – also biennial -arrived in 1993.

By that time the annual ISORA programme had been pared down to a more family-friendly scale, but sailing patterns had changed so much, with sunshine holidays afloat in warmer climes rising rapidly in popularity, that just a few years ago there actually was a move for the formal winding-up of ISORA. But happily that was averted, and the basics of the organization are still in being to provide manageable passage races for those who want them, and numbers are now modestly increasing.

Meanwhile for Dickie and Elspeth Richardson and their boys, in the late 1970s the focus of family life had increasingly moved towards their second home in Holyhead, while the pressure on the accelerator for offshore racing achievement was eased early in 1977 with the acquisition of the bare hull of an elegant Ohlson 38 which duly filled the front garden at Eshe Road North in Liverpool.

The new Ohlson 38 Matthew Walker off Holyhead SC (where Dickie Richardson had been Commodore) in 1977. Less than six months earlier, she'd been a bare shell in the Richardson's front garden in Liverpool. Photo: W M Nixon

Ready and willing. Despite the rapidity of her completion, Matthew Walker in full commission to cruise to southwest Ireland within six months of the Richardson family taking delivery of the bare hull. Photo: W M Nixon

Classic Richardson work. In the summer of 1977, the stemhead fitting on Matthew Walker, which Dickie Richardson fabricated himself, still needed a bit of cosmetic work. But it did what was needed for the first cruise. Photo: W M Nixon

There was a longterm plan to re-emphasise their interest in cruising, but being the Richardsons, once the job was there to be done, it had to go ahead at great speed, for the hull had been delivered late. The new boat – called Matthew Walker – was put afloat in time for a summer cruise to southwest Ireland in the summer of 1977. Though she was still fairy basically finished in some areas, that could be sorted in time. But meanwhile she was certainly ready for sea and Dickie – after a final rush of work on the boat which saw him put in a seven day non-stop work programme – was sent below by his family to sleep as they cleared Holyhead Harbour. He woke up 48 hours later off the coast of West Cork.

In his work as a medical consultant, he was also always prepared to go the extra mile to achieve results, and in his Liverpool days he'd been on the Project Management Committee getting the huge new hospital into commission. He put in so much of his own time on this that when the massive facility finally opened, his sailing friends assumed that he'd be rewarded in some way in the British Honours List. But the word from within was that, in the quest to get the hospital up and running, he'd been so blunt abut the inadequacies of official management that he'd offended far too many NHS sensibilities to have any chance of receiving that well-earned gong.

On retirement Dickie and Elspeth moved to Porth y Fellyn in the almost rural western corner of Holyhead Harbour where they'd converted a former Methodist Chapel into a hospitable home for sailors in which they particularly valued their proximity to Holyhead Sailing Club, where he had served as Commodore, and frequently did duty as a Race Officer while being much involved with training and junior sailing, particularly through a thriving Optimist class.

Another project which suited his talents was done in concert with his longtime sailing friend Alan Stead, another sea-minded Liverpool anaesthetist who had also retired to the Holyhead area. They managed to secure a lease on some space on the inner part of Holyhead breakwater, got themselves an old crane, and offered DIY lay-up facilities to local boats in much the same style as Tower Quay in Birkenhead in the old days.

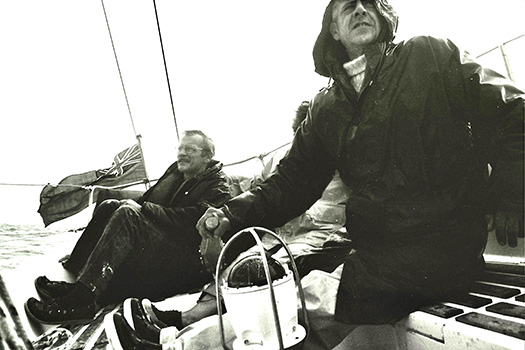

A man enjoying his new boat. Dickie Richardson finally relaxes aboard Matthew Walker after getting her completed and ready for sea in record time. On the helm is his old friend and fellow Tranmere SC stalwart Bert Whitehead, who was Honorary Treasurer of ISORA in the challenging early days. Photo: W M Nixon

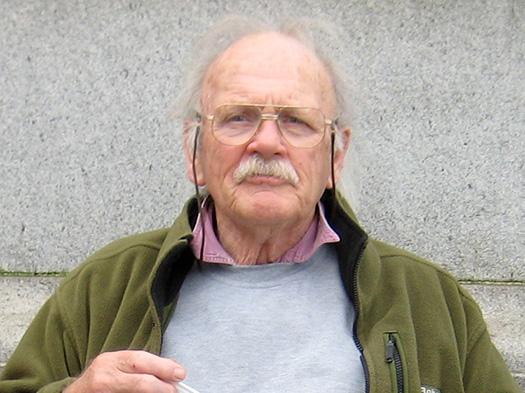

Senior sailor. A recent photo of the late Dickie Richardson. Photo: Holyhead SC

In his own sailing, Dickie threw himself into cruising the Ohlson 38 Matthew Walker with the same enthusiasm he'd devoted to offshore racing, and the Rias of Northwest Spain and the islands of the Outer Hebrides became favourite destinations. As for his talented sons, in their late teens and early twenties Angus and William did a spot of yacht design and building, the tiny and very attractive wishbone ketch Poacher being one of their products. But then William, like his younger brother Michael, went on to qualify as an advanced oil drilling engineer, and when the boys were home on leave from distant oilfields, Dickie particularly enjoyed discussion of the specialist techniques they had to use in a technically demanding profession.

Elspeth died in Holyhead on Christmas Day 2010, aged 86, and sadly for Dickie, he was also pre-deceased by his eldest son Angus in 2011. He himself soldiered on until January 2015. He would have much enjoyed his own funeral – it was a classic of its type. And should anyone suggests that the 1970s were a dull decade, rest assured they were no such thing when Dickie Richardson was around and firing on all cylinders, gruffly full of ideas and schemes and bubbling with his own quiet can-do enthusiasm. It was always a lively time in the Richardson orbit.

WMN