Displaying items by tag: Paul O’Higgins

The potent Dun Laoghaire-based JPK 10.80 Rockabill VI may now have four very busy seasons – both inshore and offshore - in her sailing CV. But the years have not dulled her performance and competitiveness, and in 2019 she had such a wellnigh perfect prize-list that her owner-skipper Paul O’Higgins has emerged as a clear winner of the Afloat.ie/Irish Sailing “Sailor of the Year 2019” title.

As most Afloat.ie readers will be aware, today was planned to see the Annual General Meeting of Irish Sailing in Dun Laoghaire, together with the Annual Conference of many of its specialist sub-groups, with the day’s business concluding in the honouring of the many and varied Sailors of the Month followed by the acclaimed announcement of the latest Sailor of the Year.

Normally this is done in early February. But times have changed in the structures of sailing and its sponsorship supports in recent years, and despite the late date, it was right for the circumstances that were in it for the ceremony to be put back by seven weeks.

But in those seven weeks, “the circumstances that were in it” have in turn been changed out of all recognition, and as we indicated last week with our report of the virtual launch of the SSE Renewable Round Ireland Race 2020, for now and the foreseeable future while Covid-19 dominates our lives, everything involving public ceremonial is going to be in the virtual world, or as the more senior among us still prefer to think of it, in cyberspace.

The start for something big….Paul O’Higgins’ JPK 10.80 Rockabill VI and Mick Cotter’s Southern Wind 94 Windfall at the start of the Dun Laoghaire to Dingle Race 2019 in which Windfall took line honours and a new course record, and Rockabill VI was overall winner. Photo Afloat.ie/David O’Brien

The start for something big….Paul O’Higgins’ JPK 10.80 Rockabill VI and Mick Cotter’s Southern Wind 94 Windfall at the start of the Dun Laoghaire to Dingle Race 2019 in which Windfall took line honours and a new course record, and Rockabill VI was overall winner. Photo Afloat.ie/David O’Brien

Call it what you may, but at the heart of it there are indisputable facts, and today there is longterm encouragement in contemplating just what Paul O’Higgins and his shipmates have achieved since 2016, and particularly during the past 12 months.

Of course, there’s a very special boat at the centre of it. And of course, her owner-skipper is renowned for surrounding himself with some of the most formidable talents in Irish offshore racing – both amateur and professional – drawn from a crew panel based around the Greater Dublin area and Cork, and based on a regular core crew.

Yet there are many boats of enormous potential in Ireland. And the talent is there at every sailing centre. But it takes a special ability, a very focused intelligence, and an extremely determined campaigner of the calibre of Paul O’Higgins to bring them all together race after race, regatta after regatta, to achieve results of the remarkable consistency logged by Rockabill VI.

The 2019 highlights alone are enough to set the tone: ICRA Nats: First Overall Coastal Class 0; Dun Laoghaire to Dingle Race: 1st overall and the first boat to successfully defend overall win in a previous race; Calves Week: 1st; Irish Sea Offshore Racing Association 2019 Championship: 1st Overall; Irish Cruiser Racing Association: Boat of the Year 2019.

Outside of sailing, Paul O'Higgins is best known as one of Ireland’s leading lawyers with a Dublin family background in which rugby and tennis were the favoured sports. But he reckons not being a cradle sailor gives a certain advantage, as he can look at boats in a coldly dispassionate way, uninfluenced by sentiment.

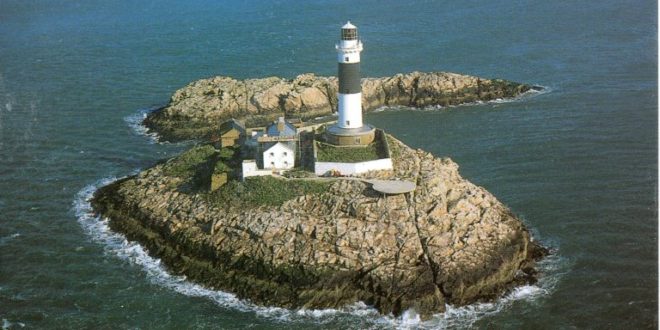

In fact, he hadn’t sailed at all until he met his future wife Finola Flanagan at College, and as the Flanagans of Skerries were the total sailing family, he soon found himself roped into sailing with his future father-in-law Jack Flanagan on a series of boats all named Rockabill after that distinctive lighthouse-topped rocky islet that is eight miles east of Skerries out in the Irish Sea, an islet big enough to provide a home for Europe’s largest colony of the rare roseate terns.

The one and only original Rockabill eight miles off Skerries is home to Europe’s largest colony of roseate terns

The one and only original Rockabill eight miles off Skerries is home to Europe’s largest colony of roseate terns

From being a visitor who might pull a rope when asked, the daughter’s suitor developed into a crewman, and as his taste for this weird but wonderful sport grew, he became a partner in the continuing succession of Rockabills, going into co-ownership with Jack in a souped-up First 30, Rockabill II.

By 1998, the balance was changing naturally with the passage of time, and Paul was becoming the pace-setter when they moved into a First 33.7 Rockabill III. He was competitive, yet no more naturally able at sport than most. An enthusiasm for playing rugby had been brought to an end by a knee injury, but he can still give a reasonable account of himself on a tennis court. However, it was the hugely complex wind-driven vehicle sport of campaigning a cruiser-racer under fair handicap rules which increasingly appealed to him.

Having made the happy discovery that he seemed to be immune to seasickness, he stepped up his level of involvement. His father-in-law had long since become eligible for the free travel pass, so the stage was reached where Paul bought him out while still with the First 33.7, and then with the turn of the millennium he was thinking of another boat slightly further up the Beneteau range, the highly-regarded First 36.7, and with her he achieved his first significant win in an IRC event, by which time he had moved his base of sailing operations to Dun Laoghaire.

Professional and family life were at their most demanding, yet somehow he found the time to campaign the First 36.7 Rockabill IV in several significant series and regattas, building up both experience and skills, while at the same time enlarging his circle of like-minded friends to create the kind of crew panel – more than twice the number of actual crew on the day - which is necessary to campaign a serious boat at this level.

With every year, however, the level became ever more demanding, and in admitting to himself that the First 36.7 was no longer cutting the mustard at the heights to which he aspired, he reckoned by 2008 that he needed to be in a Corby, and a new Corby 33 was what he could most comfortably afford.

With the Corby 33 Rockabill V, Paul O’Higgins had many successful years. She is seen here racing at the ICRA Nationals 2013 at Tralee Bay. Photo: Robert Bateman

With the Corby 33 Rockabill V, Paul O’Higgins had many successful years. She is seen here racing at the ICRA Nationals 2013 at Tralee Bay. Photo: Robert Bateman

Rockabill V, the Corby 33, became a familiar sight on the circuit, always noted for putting in an interesting and often podium-gaining position, as he’d linked up with that notably serious and singularly-talented sailor Mark Pettitt.

Yet the O’Higgins boat was almost invariably guaranteed to appear at Calves Week, that special four-day amalgam of West Cork Regattas out of Schull early in August, a fun event with an underlying level of quite serious racing which fitted well with the family’s regular summer holidays in West Cork in August.

For a busy man ashore, his commitment to getting afloat as much as possible was remarkable, and his willingness to take part each year in an interesting series of regattas and events saw the range of his crew panel increasing. If you were as keen as Paul O’Higgins, then as a committed panel-member you were certain to get sailing. And with first places recorded in various series which ranged from Scotland to Kerry, plus regular participation in Dublin Bay where he sails from the Royal Irish YC, Rockabill V made frequent and regular appearances in the frame.

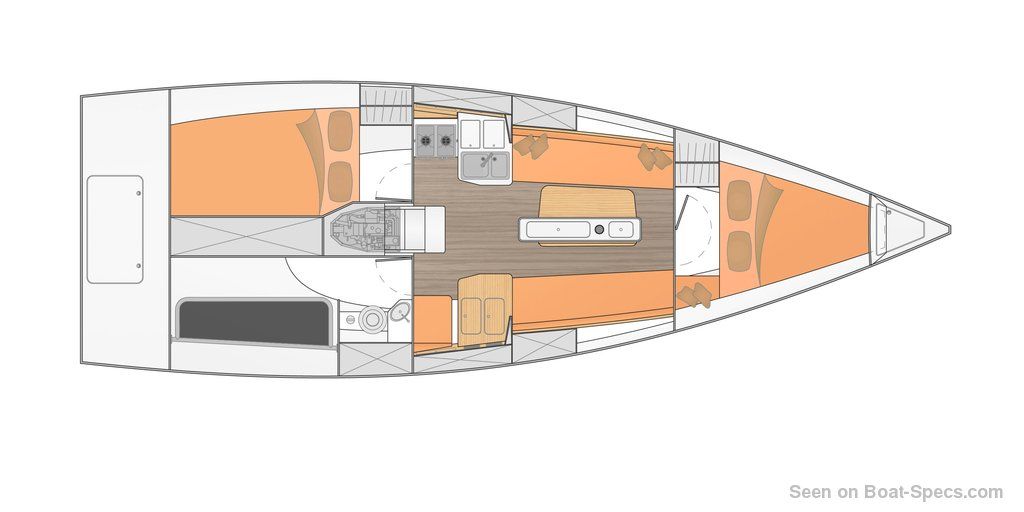

But by 2014 he began to feel that he’d gone about as far as he could with the Corby 33. She was a very interesting boat, unforgiving in some ways yet rewarding in others. But nobody would call her luxurious, let alone comfortable. That said, Rockabill V was still winning races. But when a new boat called the JPK 10.80 appeared from a specialist yard in France in the Spring of 2014, his interest was piqued by the fact that she had race potential, yet with her considerable beam, twin rudders, and roomy and comfortable accommodation, she was about as different as possible in concept from the Corby.

If he was going to make a change, why not make a complete one? The J/109 seemed an attractive idea, but when the class finally started to take off in Dublin Bay, the marque was no longer being built. This “new” Dublin Bay One-Design was a class made up entirely of pre-owned boats. Yet Paul O’Higgins had become accustomed to buying from new. Second-hand just wasn’t his thing.

He looked again at the JPK 10.80, and when one of the very first turned up from France to race Cork Week 2014, he was very taken with her, despite the fact that in straight sailing, the crew clearly weren’t getting the best from her, while their confusion with Cork Harbour courses compounded their problems.

Paul O’Higgins bided his time until July 2015 when - despite the pressure from the J/109 lobby - he placed an order for a JPK 10.80. It was a decision soon supported by events, with a JPK 10.80 winning the Rolex Fastnet Race overall in August 2015, and then in December a JPK 10.80 cruising the Pacific was briefly taken out of her cruising reverie, kitted out with racing sails by Gery Trentesaux’s Fastnet-winning crew, and promptly went out and won her class in the Sydney-Hobart Race.

Something completely different – Rockabill VI newly arrived in Dun Laoghaire, April 2016 Photo: Afloat.ie/David O’Brien

Something completely different – Rockabill VI newly arrived in Dun Laoghaire, April 2016 Photo: Afloat.ie/David O’Brien

With her strong but light construction and minimalist yet comfortable layout, Rockabill VI represented a new world of offshore racing.

With her strong but light construction and minimalist yet comfortable layout, Rockabill VI represented a new world of offshore racing.

Yet perhaps the best thing of all about having placed his order back in July before the boat was achieving stellar results was that it entitled him to visit the new factory near Lorient where the boat was being built. He went there a number of times, finding it an inspiring place of exceptional cleanliness and precision, while the dedication of designer Jacques Valer and company founder Jean-Pierre Kelbert set an impressive tone.

The first win – Paul O’Higgins on the helm as his new JPK 10.80 Rockabill VI sweeps into Dublin Bay to record her first offshore win, a cross channel ISORA race in May 2016

The first win – Paul O’Higgins on the helm as his new JPK 10.80 Rockabill VI sweeps into Dublin Bay to record her first offshore win, a cross channel ISORA race in May 2016

To say that Paul O’Higgins was well ahead of the Irish curve in placing such an early order for the JPK 10.80 which was to become Rockabill VI in 2015 is surely under-stating the case. He’d the right boat on the way for delivery in April 2016, and for four years now he has been honing a boat-and-crew management and campaign technique which has been paying increasingly improved dividends, while there’s no doubt that for all his forensic approach to boat selection, he and his many shipmates have developed an affection for Rockabill VI which goes beyond the utilitarian.

“Doing what she does best” - Rockabill VI provides speedy yet controlled sailing in this vid below:

The way that the extensive crew panel is made up is instructive. It’s only very rarely indeed that Paul himself isn’t on board, and with him are the “amateur core” based around his son Conor and Ian O’Meara, while Mark Pettit is the longterm professional, with four times Olympian Mark Mansfield increasingly part of the scene for the last three seasons.

The Flanagan family’s sailing influence continues as Paul’s wife Finola is part of the panel, as too is Mark Pettit’s wife Anna Walsh, who for the past couple of seasons and more has been in charge of the food, as mentioned in last week’s Round Ireland preview.

The power team – Rockabill VI with Peter Wilson on the helm and Mark Pettit on mainsheet in the early stages of the D2D Race 2016. Photo: Afloat.ie/David O’Brien

The power team – Rockabill VI with Peter Wilson on the helm and Mark Pettit on mainsheet in the early stages of the D2D Race 2016. Photo: Afloat.ie/David O’Brien Successful combination - Peter Wilson and Paul O’Higgins. Photo: W M Nixon

Successful combination - Peter Wilson and Paul O’Higgins. Photo: W M Nixon

The legendary Peter Wilson was of course on board for the first Dingle Race win in 2017, while other longterm hands who have shown they can fit in with the Rockabill VI way of campaigning include another O’Higgins son, Fergus, together with noted Dun Laoghaire star Kieran Tarbett and the RIYC’s Oisinn Collins. Also there is Conor Kinsella – from Offaly, and originally a Fireball sailor – with James Gunn from Dublin and John Kelly from Cobh.

A (very) brief relaxed moment for a crew photo as Rockabill VI (well in the lead) approaches the Fastnet Rock during the 2017 D2D with (left to right) Mark Pettit, Ian O’Meara, Rees Kavanagh, Conor O’Higgins, Peter Wilson, Ian Heffernan and Paul O’Higgins. Photo: Will Byrne

A (very) brief relaxed moment for a crew photo as Rockabill VI (well in the lead) approaches the Fastnet Rock during the 2017 D2D with (left to right) Mark Pettit, Ian O’Meara, Rees Kavanagh, Conor O’Higgins, Peter Wilson, Ian Heffernan and Paul O’Higgins. Photo: Will Byrne

Maintaining viable relationships of friendship and shared purpose with such an eclectic group of shipmates is quite a project in itself, but Paul O’Higgins takes it all in his stride with an affable and interested presence, and an incredibly good memory. 2019 was truly The Beautiful Season for Rockabill VI, but in the way of the O’Higgins campaign style, the focus has long since been on 2020 with its peaks in the SSE Renewables Round Ireland Race and festivities in Cork.

It’s West Cork, and the sun shines – Rockabill on track for victory in Calves Week at Schull. Photo: Robert Bateman

It’s West Cork, and the sun shines – Rockabill on track for victory in Calves Week at Schull. Photo: Robert Bateman

Yet with everything on hold on a day-to-day basis for the time being, this weekend we can cheer ourselves by contemplating the wonder of Rockabill VI’s 2019 season. Perhaps the most attractive aspect of the Paul O’Higgins’ approach is that he’s a genuine sportsman who loves his sailing. Thus although he knows each November that organiser Fintan Cairns will be setting an impossible handicap for Rockabill VI’s challenge in the DBSC annual Turkey Shoot, his love of sailing means he’ll still be out there racing.

Were this a traditional profile of a noted sportsman, we would of course reveal Paul O’Higgins’ age. But when you’re dealing with dedication, enthusiasm, managerial ability and sheer sailing toughness at this level, mere chronological age becomes a meaningless metric. So let’s say that Paul O’Higgins, Afloat.ie/Irish Sailing “Sailor of the Year 2019”, is a life member of the sailing team from Tir na nOg, and that’s all there is to it.

With Mark Mansfield trimming from the lee deck, Rockabill VI finds just enough breeze to win the final ISORA race of the year – and the championship – in Dublin Bay, September 2019. Photo: Afloat.ie/David O’Brien

With Mark Mansfield trimming from the lee deck, Rockabill VI finds just enough breeze to win the final ISORA race of the year – and the championship – in Dublin Bay, September 2019. Photo: Afloat.ie/David O’Brien