#chillout – As the sailing community ponders the global fall-off in casual sailing numbers, leading sailor Ken Read reckons that one of the reasons is because our sport is getting too serious. He says it's time for most sailors to take a chill-pill. W M Nixon muses on how this suggestion is reflected in Ireland.

Ken Read, former Volvo World Race skipper of notable success, and holder of heaven only knows how many major championships and sailing records, is these days the President of North Sails. A nice little earner, you might say. Let's hope so. But there's much more to it than that.

Being President of North is top of the tops. Time was when the head honcho at Hood Sails, particularly when it was Ted Hood himself, was the special one, filling a unique and highly visible position in the big picture. And other leading global sailmaking brands have also been on this pinnacle from time to time. But these days, Ken Read is the man. He holds the key point in the middle of the triangle formed by the marine industry on one side, the local, national and international sailing organisations on the other, and the sailors themselves on the third. By the nature of their trade and the way it operates, sailmakers are connected every which way, and the world's top sailmaker speaks for all.

So when the President of North Sails advocates a change of sailing attitude at a recent convention of J Boat dealers in America, the sailing world is well advised to take notice. It may be that he said things that many of us have been saying in a different form for many years. But the fact that it was said by the President of North Sails, and said in a concise and forceful yet good-humoured way, uniting many strands of thinking, was something which gave it an impact which no other leading commentator could achieve.

But then Ken Read has always been unique, ever since he was clearly having the time of his life as he rose to international prominence through the ranks of the J/24 Class. He seems to have an enviable gift of knowing how to party when it's right, and how to sail intensely well when the situation demands it. He inspires a very special loyalty among crews, and an admiration and affection among people generally when the big sailing events come to town.

Galway's Volvo Race stopovers provided the classic case in point. Long before selfies became all the rage, just about every club sailor who was next or near Galway docks came proudly home with a photo of themselves and their mates with Kenny Read. As for the great man himself, as the fleet raced away down past the Cliffs of Moher at breakneck speed, he still found time to post a message saying how much he'd enjoyed his time in Galway, sending out a cheery stream of consciousness about this great harbour town with a pub on every corner, and everybody in those pubs wants to buy you a beer, and the greatest golf links he'd ever played down at Doonbeg, so what's not to like?

But just in case anyone was in any doubt about how he'd fully immersed himself in the Galway and Irish thing, as the fleet had headed out through the Galway lock, here was the man himself in a Paddy hat you'd need a licence for. We gave you a glimpse of it at the top this morning, but the full impact needs a bit of space, so here it is again in untrimmed glory. It's something to be savoured, though I doubt you'll find it displayed on the walls of the North Sails boardroom.

The Full Monty. Only a man very comfortable with himself would set out to go to sea in the most public way possible, and attired like this. Photo: David Branigan

Ken Read got his main point made immediately at the J Boat gathering. He wants recreational racing to take a chill pill. He argues that the message is simple: the harder we play, and the more we invest in our recreation, the fewer people will want to take part in the game.

You'd guess the key phrase is "recreational racing". In other words, he's talking of what you and I do in club racing, at local, regional and class championships, and in offshore races on the nearest bit of open water.

Obviously we're not talking Olympic aspirations, or indeed sailing towards one of the 143 world titles which sailing offers to dedicated participants. But if we did want a scapegoat for people being turned off sailing, I'd be minded to blame the dominance of the Olympics in the public's thinking about minority sports.

The Olympic circus is the sow that eats others' farrow. It takes up little specialist sports, and then forces them into unnatural shapes in order to attract their brief moment of global Olympic attention. And once it has them hooked, it dictates the amount of media interest they have to continue to generate in order to stay in the Olympic lineup. To do this, they contort themselves and their events even further in every unnatural way possible in order to get what is, ultimately, no more than the most ephemeral passing interest, and that from people whose attention really isn't worth the effort in the first place.

Sailing is essentially about participation, it's not naturally spectator friendly. The only truly absorbing way to watch a yacht race is by taking part in it, and enjoyable yacht races can take many forms. But as the Olympic juggernaut gathered speed and power during the past eighty and more years, the Olympic "ideal" of the purest possible yacht racing, with windward starts all staged from committee boats as clear as possible from the influence of the land on the breeze, and preferably in a tide-free zone, became the dominant theme. Even the most homely club sailing programmes found themselves being forced by fashion into the strait jacket of aping the sacred "Olympic course", and raced by one designs too.

But in his presentation to the J Boat men, Ken Read has blown it all out of the water. The Must Read list is:

- Rally and pursuit races are fun, and gaining in popularity.

- Get rid of the AP flag; people want to sail, not float around waiting for perfect conditions.

- Stop worrying that the starting line is off by 5 degrees; start the race

- Get rid of uncomfortable gut hiking off the lower lifelines

- All spinnakers should be coloured; no more white!

- Start some races downwind

- More variety of courses; not only W-L

- Increased use of reaching legs, particularly with boats that can plane

- Involve youngsters more in big boat sailing; not all want to do dinghies.

- More public access to the water, then sailing would become even more important

- Pros should be helping the amateurs by being available at regattas to give help and guidance.

It's a wish list which carries a couple of real stings in the tail. Making recreational waters more publicly accessible immediately suggests that you'll need public employees and regulators to run such access amenities, not only in supervising the launchings and retrievings, but also in keeping the facilities in good order. With experience painfully teaching us that what's everybody's business is nobody's business, the increase of public access to an intensely personal vehicle sport like sailing is quite a challenge.

As for suggesting that the top pros should be available at regattas to help amateurs, that's a tricky one. With much of modern sailing already having a pro-am mix in many events, you can see that there'll be competition to get the attention of top pros, and money will talk. That said, every so often you hear of sailors of truly global stature such as Robert Scheidt of Brazil, whose presence at some ordinary event manages to enhance everyone's day afloat.

But as for Irish sailing learning from the Read programme, it's really more a case of learning anew. For instance, this business of getting all ages involved in big boat racing. Well, we featured it here a couple of weeks ago with our analysis of the success of Dublin Bay Sailing Club. Inevitably, some subsequent commentators complained that while Dublin Bay may provide dinghy racing at mid-week, Saturdays are dominated by keelboats and particularly cruisers. Instead of being an undesirable situation, this sounds rather like what Ken Read is advocating.

The fact is, cruisers are simply much less hassle to organise for weekend racing. They're afloat and ready to go, you can even use them as changing rooms, they don't need crash boats, and they can provide that easygoing sociable atmosphere which needn't involve a debilitating level of commitment. Yet it gets people out enjoying sailing - and they come back for more. Dinghies by contrast are a flighty bunch, and you've no sooner gone to all the trouble of setting up regular Saturday racing for them than you find they're on their trailers, haring down the motorway to some distant regional championship.

Read's opening suggestion about rally and pursuit races will ring a special bell for anyone whose formative sailing years were at Ballyholme Bay on Belfast Lough. Although BYC is now the north's leading performance and dinghy events club, its membership is eclectic and its fleet diverse, so for as long as anyone can remember, they concluded their traditional season with a pursuit race.

These days their season is virtually year-round, but the Menagerie Race, as it's sometimes known, is still sailed every September. It generates excitement at all levels. Beforehand, with handicaps being taken at the start, there's the fascination of the handicapper's calculations to allot starting times for each class and the many individual boats from small dinghies to large cruisers. Then on the day itself, the weather is of special interest as different conditions better suit different boats. And then the finish is one of high excitement, as the final leg is sailed across the bay towards the line close off the club, a time of drama as everyone from biggest to smallest closes in towards a finish which may be decided by inches – it has not been unknown for a couple of crewmembers to be straining on the stemhead as they hold the spinnaker pole out forward well beyond the pulpit to gain a couple of feet.

Unlike your usual handicap race where the result may have to wait for the finish of the last boat across, a pursuit race provides a finish which is instantly satisfying for the winner at least, and also for spectators of limited attention span, which is just about all of them these days.

Lufra in her youth, tearing along on the Clyde in the 1890s. Photo courtesy Iain McAllister

As anyone with experience of sailing at Ballyholme will know, the end-of-season Menagerie Race, as its quaint name suggests, goes back a long way. But it's usually better known as the Lufra Cup, and has been known as such since the mid-1940s, when it was presented for a race which was already a much-loved part of the programme.

So who or what was Lufra? In the 19th and early 20th Centuries, the romantic Scottish-flavoured novels of Sir Walter Scott were best sellers. As the new sport of yachting developed, on both sides of the North Channel the work of Scott provided a fertile source of interesting names for boats – an entire class, the 18ft Belfast Lough Waverleys established 1903, derived all their evocative names from his long sequence of Waverly novels.

Lufra was a dog, but a noble and swift one. He figured in Scott's poem The Lady of the Lake (1810), a title which was itself borrowed from the Arthurian legend, but equally has since been borrowed again to name more inland-cruising water-buses than is decent. Whatever, Scott's long narrative poem recounted the usual bloodthirsty Scottish melodrama, set this time in the Trossachs. But from a cast which was large if not quite in the thousands, the character who stays in the mind is "brave Lufra, the fleetest hound in the North".

You'd think a unique and swinging name like that – I've always heard it pronounced "loof-rah" – would be encouragement enough to build a boat, and one of gallant performance and character at that. But it wasn't until 1894 that the first boat we know of called Lufra appeared from the busy G L Watson design office. Built by P R MacLean of Rosneath for T K Laidlaw of Glasgow, Lufra came at an interesting time of design development. With the appearance of the spoon-bow with the successful 10-Rate Dora in 1891 (she also had a centreboard, but that's by the way), the Watson office had started moving away from the clipper or fiddle bow, and with the big boats Britannia and Valkyrie in 1893, they developed a new kind of keel, more definably an appendage to the hull, and with a more marked toe which greatly improved windward ability.

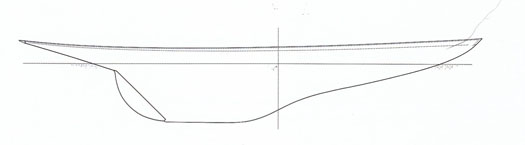

The timeless profile of Britannia in 1893. She still looked up-to-date at the end of her life in 1936, by which time her shape was also used for offshore racers and fast cruisers.

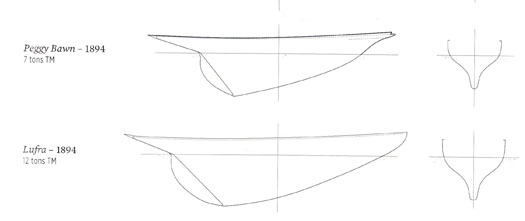

The profiles and hull sections of Peggy Bawn and Lufra. Though they were broadly similar below the waterline, the fact that Lufra had an above-water profile similar to Britannia made her seem much more modern

But most yachtsmen, particularly those with an interest in occasional cruising, are conservative types. So for several years the Watson team were still being commissioned to design new boats of an older type, with fiddle bow, fairly slack and deep hull sections, and a deep heel to the keel. Hal Sisk's 1894 Watson-designed, Hilditch-built classic Peggy Bawn is a good example of this type. She may have been designed a year after Britannia, but her hull shape is light years away from the high-performance Britannia, whose hull continued to look state-of-the-art right up her unhappy scuttling by Royal Command in 1936.

Admittedly when launched Britannia was though of solely as a racing boat, but by the time of her enforced demise, offshore racers and fast cruisers were replicating her hull type. As for Lufra in 1894, she was somewhere between the two types. She had a spoon bow but similar hull sections to Peggy Bawn. However, above the waterline, the 40ft LOA 12-tonner Lufra was a miniaturised image of Britannia.

She was first brought to Northern Ireland from the Clyde in 1937 by Howard Finlay, who sailed on both Belfast and Strangford Loughs. Anyone who thinks of the 1930s and '40s as a dowdy period in Ireland north and south will find the photos of Howard and his mates aboard thenewly-bought boat something of an education. Howard himself had the chiselled good looks of a matinee idol designed to have a pipe clinched in his teeth, while his crew had the style of supporting actors in a Jimmy Cagney movie, or even an early Bogart film. You expect them to burst into exuberant song at any moment, or start shooting.

The gang's all here. Howard Finlay (second left) and his crew of characters aboard Lufra in 1938. Photo courtesy Paul Finlay

Initially in the Finlay ownership, Lufra was white, but later he painted her black which emphasised the Britannia resemblance, while she was kitted with tan sails which looked very handsome indeed. While still white, she took part in Ballyholme's end-of-season Menagerie Race of 1943, which she won. But as there was no decent prize available, Howard put up the Lufra Cup for the 1944 race.

You might wonder that racing was going on at Ballyholme in the midst of World War II. But as Belfast itself was such a hectically busy place with building and repairing warships, aircraft and so forth, it was decided that it made sound welfare sense to encourage the key workers and managers, most of whom were doing incredibly long hours, to keep up their sporting activities in their brief free time. Thus it was only at the height of the war in 1940 that all sailing was cancelled, and by 1943 sailing was busy again, as there was no petrol available for motoring and other rival vehicle pursuits.

In those days, the Ballyholme Bay class, curious little 23ft keelboats with a tiny coachroof, were the hot racing things of Ballyholme despite not having spinnakers - they just whiskered out the jib. But despite this, as the finish of the 1944 race approached with a half mile broad reach across the bay, the top Ballyholme Bay Class boat, Jack Cupples' Caleta, seemed set for a win. But coming up rapidly from astern, Howard Finlay brought Lufra gybing smoothly round the last mark. Somehow his crew had the enormous spinnaker up and drawing for that final half mile leg, and they swept by Caleta to take the cup on the line, and a blurry Box Brownie photo records it all.

Lufra sweeps across the line to win the 1944 "Menagerie Race" at Ballyholme, and so become the first winner of the Lufra Cup. Photo courtesy Paul Finlay.

It was pursuit racing at its best, as close astern was one of the 30ft LOA Belfast Lough Stars (near sisters of the Dublin Bay 21s, but setting a gunter mainsail instead of gaff with tops'l) and then the rest of the fleet were in within minutes. The handicapper who'd set the starting times was delighted. But some Bay Class types weren't quite so chuffed, and suggested that as Howard Finlay had presented the new cup, the right thing to do would be to hand it on to the boat which finished second. He told them very precisely what they could do with that notion.

Over the next few years, Lufra was in the frame now and then, though the handicapper made sure she never won her cup again. But by the 1950s she was becoming very expensive to run, and in those recessionary times, she was unsellable. In fact, her lead ballast keel was worth more than the boat complete. So the keel was removed and sold, and this most handsome boat was laid up afloat in the little quarry hole harbour in Donaghadee in the hope that the good times would return. But for Lufra, the good times never did return. She rotted and sank, and when the quarry hole was being excavated to become Ireland's first coastal marina in the late 1960s, the last surviving relics of "the fleetest hound in the North" were dredged up and taken away to a landfill.

The restored 1903-built Belfast Lough Waverley Lilias (Jeff & Janet Gouk) was the 2011 winner of the Lufra Cup. Photo: W M Nixon

Yet the Lufra Cup lives on, and the list of its winners gives us a spare yet eloquent account of the sailing story at Ballyholme. Most appropriately, in recent years some of the winners of this trophy honouring Walter Scott's "fleetest hound in the North" have been boats of the old Waverley Class, now undergoing revival with impressive restoration projects. And years ago, when I was battling with racing Insect and Swallow class boats at Ballyholme, a frequent winner was a boat like a big sister of Lufra, Harry Townsley's 15-ton gaff cutter Anolis, which could go like a train on a reach in the kind of race Olympic idealists might sniff at, yet it was exactly what the punters wanted.

The winners over the years have included everything from a Laser (1993, and again in 2007, when sailed by Puppeteer designer Chris Boyd) to 1720s, with just about every type in between, and up or down too. I don't think an Optimist has ever won it yet, so current top cruising man Ed Wheeler has held the record for smallest winning boat since 1958, when he took the cup with his International Cadet.

Many of today's junior sailors may know little of the Cadet, though it still sails. Basically, it was a pram-bowed 10ft chine dinghy built (usually as DIY) in ply to a design by Jack Holt, who later designed the Mirror. The concept of the Cadet was as a mini-version of grown up racing dinghies, a proper training boat with a Bermudan rig which benefited from fine tuning, and setting a spinnaker.

But they were so very very small. The great Wic McCready, Northern Ireland's top junior sailor in his day, was a big lad who grew quickly. In his final year racing Cadets, in light weather he might be seen reposing with as much comfort as he could find by sticking his feet out over the stern. So when you saw a Cadet with Anolis thundering up astern and the finish line just feet away, it was very much little and large. As Ed Wheeler recalls it, crossing the line with Anolis's battering ram bowsprit right above your head concentrated the mind something wonderful.

So with the popularity of racing such as that provided for all ages in cruisers by Dublin Bay SC, and the golden thread of the Lufra Cup pursuit race at Ballyholme, it seems to me that maybe we're fulfilling many of the Ken Read objectives in Ireland already. As to setting unorthodox courses sometimes with pier starts, here in my own home port of Howth the 116-year-old Howth 17s were for a time strait-jacketed into Olympic courses which were much less stimulating than their time honoured courses in the interesting waters in and around Ireland's Eye, with handy pier starts just a few minutes sail from the anchorage, instead of having to sail for miles in search of the committee boat.

The Howth 17s sweep along in style after making a pier start during the 1930s. Having been making pier starts since 1898, there were attempts after 2000 to get them to use Committee Boat starts. But these days they find that a pier start, with the line only a very few yards from the harbour anchorage, is the option preferred by most crews. Photo: W N Stokes

The result is a revival of Howth 17 racing, particularly in the amorphous area of Saturday afternoon racing, when modern life presents too many distractions and other duties to people who would otherwise be sailing. The convenience and charm of handy starts and racing in very inshore waters seems to have spread, and the word is that the SailFleet J/80s, which will be based in Howth again this year, would also like some convenient pier-starting races in their programme.

So maybe we're going to reach the stage of Olympic sailors being told that they're welcome to keep their sterile starts, and windward-leeward courses far from land, the rest of us prefer a different emphasis. Except, of course, that at the 2012 Olympics, for the final races the fleets were brought very close inshore to facilitate spectators at Weymouth.

It seemed like a case of the tail wagging the dog. And if the racing had been continued offshore, with clear winds and plenty of it, Ireland might well have come home from the 2012 Olympics with a Sailing Bronze. So maybe the real message is, let's make sailing more fun...........except for the Olympics.