#rorcsrbi – For twelve days, Ireland's sailing and maritime community followed with bated breath while the fortunes of Liam Coyne and Brian Flahive with the First 36.7 Lula Belle waxed and waned in the storm-tossed 1802-mile RORC Sevenstar Round Britain & Ireland Race. Last Saturday, they triumphed, winning the two-handed division and two RORC classes in this exceptionally gruelling marathon. W M Nixon delves into the human story behind the headlines of success.

It used to be said that Irish seamanship was the skilled and stylish extrication of the vessel from an adverse and potentially disastrous situation in which she and her crew shouldn't have been next nor near in the first place.

While we may have moved on a bit from that state of affairs with a less devil-may-care approach to seafaring, there's no escaping the fact that this morning we can now look back at two remarkable Irish victories in topline international offshore events in recent years in which both crews overcame major setbacks and situations, rising above very adverse circumstances which could well have deterred sailors from other cultures where the philosophy is not underpinned by the attitude: "Ah sure lads, things aren't good. Not good at all. But let's just give it a lash and see how we go".

It was seven years ago when a full entry list of 300-plus boats was slugging westward down the English Channel in the first stages of the Rolex Fastnet Race 2007. Already, the start had been postponed 24 hours to allow one severe gale to go through. But in an event still dominated by the spectre of the 15 fatalities in the storm-battered 1979 race, most crews were hyper-nervous about another gale prospect, and by the time the bulk of the fleet was in the western English Channel, many succumbed to the allure of handy ports to lee such as Plymouth, and in those early days of the race something like 48% of the fleet retired.

But aboard Ger O'Rourke's Cookson 50 Chieftain out of Kilrush on the Shannon Estuary, they were well into their stride. That year, the boat had already completed the New York to Hamburg Transatlantic Race, placing second overall. But owing to her Limerick owner's quirk of never confirming the boat's entry for the next major event until the current one is finished, they found themelves only on the waiting list for that year's already well-filled Fastnet Race entry quota.

Chieftain was 46th on that list. Yet while those who had made an early entry fell by the wayside, steadily this last-minute Irish star rose up the rankings. With three days to go, Chieftain got the nod. They went at the racing after the delayed start as though this had been a specific campaign planned and carefully executed over many months with a full crew panel, instead of a last-minute rush where crew numbers were made up by a couple of pier-head jumpers who proved worth their weight in gold.

Yet then, as the new strong winds descended on the fleet as the group in which Chieftain was already doing mighty well was approaching the Lizard Point, the troubles started, with gear failing and boats pulling out left and right. But the Irish boat was only getting into her stride. A canting-keeler, she could be set up to power to windward in a style unmatched by bigger craft around her. Approaching the point itself in poor visibility to shape up for the fast passage out to the Fastnet Rock with even faster sailing, things looked good. And then the entire electronics system aboard went down, and stayed down.

Here they were, not even a third of the way into a race which promised to be rough and tough the whole way, but a race in which they would at least have been expecting know their speed, performance and position down to the most minute detail. Instead, they were in an instant reduced to relying on a couple of tiny very basic hand-held GPS sets, and paper charts.

Ger O'Rourke's Chieftain sweeps in to the finish at Plymouth to win the 2007 Rolex Fastnet Race overall

Those paper charts were little better than pulp by the end of a very wet race in an inevitably extremely wet but searingly fast boat. But they did get to the end, and with style too. They won overall and by a handsome margin. It was the first-ever Irish total victory in the Grand National of Ocean Racing. The owner-skipper had to go up the town to buy himself a clean shirt for the prize-giving in the Plymouth Guildhall.

Yet when Ger O'Rourke's Chieftain swept into Plymouth and that triumph just over seven years ago, the boat was in much better racing shape than Liam Coyne's First 36.7 Lula Belle when he and Brian Flahive completed the final few miles back into Cowes around midday last Saturday to finish the 1802-mile Sevenstar Round Britain & Ireland Race.

Lula Belle had many gear and equipment problems after an extreme event where the natural pre-start nervousness had been heightened by a reversal by the Race Management of the originally clockwise course as the 10th August start day approached. It would have been folly to send the fleet westward into storm force westerlies in restricted waters. Eastward was the only sensible way to go.

Then the arrival of the remains of Hurricane Bertha – which seemed to be finding new vigour – led to new tensions with the start being postponed from midday Sunday to 0900 Monday. It was disastrous from a general publicity point of view. But it would have been irresponsible to send a fleet of boats – some of them mega-fast big multihulls – hurtling towards the ship-crowded narrows of the Dover Straits beyond the limits of control in a Force 11-plus from astern.

Even when they did race away, it was with a Force 8 plus from the west, with the Irish crew recording 42.5 knots of wind aboard Lula Belle (and from astern at that), before they lost all their instruments from the masthead on the first night out. For a double-handed crew, that was a very major blow. Two-handers are allowed to use their auto-pilot, and if all the wind indicators are functioning in proper co-ordination with it, then the boat can sail herself along a specific setting on the wind. It's as good having at least one extra hand – and a skilled and tireless helmsman at that - on board.

Lula Belle on her way out of the Solent with 1800 miles to race and everything still intact. Photo: Rick Tomlinson

There it was – gone. After the first night at sea, Lula Belle's masthead was bereft of everything except an often defective Windex. Photo: W M Nixon

Fortunately the auto-pilot itself was still working on its own, and they became well experienced in setting the boat on course and then trimming the sails to it in a continuous process which worked well except when the seas were so rough and irregular that they had to hand steer in any case, albeit with the apparent wind indicated only by the sole survivor of the masthead units, the little standard Windex. But it must have been damaged when everything else was swept away, as from time to time it jammed. When that happened, the only wind indicators available to the two men were the Sevenstars battleflag on the backstay, the tell-tales on the sails, or a moistened finger held aloft, as neither were smokers.

Despite this, they made their way north through the North Sea and all round Scotland and its outlying islands and right down the western seaboard of Ireland as far as the Blaskets before things went even more pear-shaped. In fact, the wheels came off.

Their ship's batteries had been showing increasing reluctance to hold power, essential for the continuing use of the autohelm and the most basic need for lighting and any still-usable electronic equipment including the chart plotter. But thanks to a trusty engine battery, they could start the motor to bring the ship's batteries back up to short-lived strength. Yet while approaching the Blaskets, the engine refused to start, and nothing they could do would coax it back to life. Inevitably they lost power, and for the final 495 miles of the race – the equivalent of 78% of a Fastnet Race - the boat was sailed and navigated entirely manually, with the required navigation lights provided by modified helmet lamps.

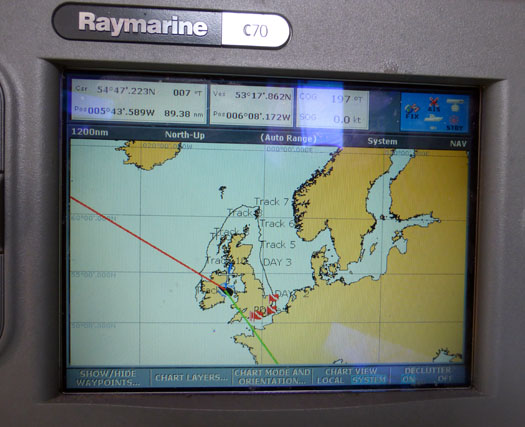

The chart plotter shows only too clearly where power was lost completely just north of the Blaskets. Photo: W M Nixon

Yet they finished well last Saturday, around noon on August 23rd after twelve days racing. They won the two-handed division overall, they won Classes IV & V, and they placed sixth overall in a combined fleet in which big boats with a strong element of professional crewing dominated. So who are Liam Coyne and Brian Flahive, and what about Lula Belle, the heroine of the tale?

Afloat.ie caught up with them on Thursday morning in Dun Laoghaire marina, where they'd got home an hour or so before dawn to grab a quick sleep of a few precious hours before awakening to more sunshine than they'd experienced for a long time, as the Round Britain & Ireland was raced across an astonishingly sunless sea. As for the 450-mile passage home to Dublin Bay, it had been achieved through mostly miserable weather and an enforced and brief stop in Plymouth to try to get a final solution to the continuing electric problems, which had defeated the finest minds in Cowes.

But such hassle fades when the return home is completed, and the Lula Belle crew were in great form. They complement each other. Brian Flahive is from Wicklow and he's a studious, thoughtful type. He turned 31 just three days after the win, making it his best birthday ever, and a fitting highlight in a sailing CV which continues to develop, and began with local sailing and training courses with Wicklow Sailing Club after his sister Carol had acquired a Mirror dinghy.

Since then, Carol's seagoing has taken a slightly unexpected turn as she found her vocation in the lifeboat service, and that is now her main interest afloat - she is a helm on the Wicklow lifeboat. But her younger brother Brian was soon hooked on pure sailing, and from the Mirror he soon went on the 420s where his enthusiasm was noted by local keelboat owners, who in turn recruited him aboard, and soon he was noted by those assembling offshore racing crews too.

When you've talent, enthusiasm and time available, the word soon gets about in the limited recruiting pool available to Ireland's offshore racing folk. Soon, young Flahive was spreading his wings with his home port's biennial Round Ireland race, and participation in Irish Sea Offshore Racing. He proved adept at and interested in two-handed sailing in particular, and soon got to know another relative newcomer to the Irish Sea offshore racing scene, Liam Coyne.

Liam Coyne is 47, and something of a force of nature. There's a mischievous twinkle to his eye, but there's a very serious side to him too, even if – as when he admits he's extremely competitive – it's done in the best of humour. He's from Swinford in County Mayo, where any knowledge of boating might relate to the big lake of Lough Conn nearby. But as he left Mayo for the USA just as he was turning 20, his passionate sailing involvement has been entirely generated during his more recent life in Dublin.

There's a mischievous twinkle, but Liam Coyne makes no secret of his competitive nature. Photo: W M Nixon

Back in the 1980s, well before Australia took off as the destination of choice for energetic and ambitious young Irish people, America was still the Land of Dreams. Coyne's teacher of English in Mayo was so sure of this that one of his courses was built entirely around the USA's immigration examination. He did a good job, young Coyne made the break, and he started to fulfill his ambition of getting to all the American states by spending time – sometimes quite a lot of it – in 26 of the States of the Union. Eventually with a winter approaching, he found the building site he was quietly working on in Boston was due to close completely for the colder months. But he managed to swing a job selling Firestone tyres (sorry, "tires") from the local agent's shops. It was a union created in heaven. Liam Coyne and tyres – the bigger the better – were made for each other.

He prospered in the tyre business in Boston and enjoyed his work, but there was always the call of home and a girl from Swinford who had qualified as a teacher. So he came back to Ireland in 1998, set up in the tyre business in Leinster, married the girl and settled down in south Dublin to raise a family.

Came the boom years, and the tyre business prospered mightily. Liam Coyne Tyres had five depots and employed 48 people. He was mighty busy, but seeking relaxation. So on the October Bank Holiday Monday in 2005, he and his wife went to the Used Boat Show at Malahide Marina and by the time they left, Alan Corr of BJ Marine had sold them a handy little Beneteau First 211, their first boat.

His knowledge of boats and sailing was rudimentary to non-existent. His maiden voyage, the short hop of 12 miles from Malahide to his recently-joined new base at Poolbeg Y& BC in Dublin port, took all of 14 hours as the tyro skipper battled with the peculiarities of tide and headwinds, happily ignoring the potential of the little outboard engine on the transom even though, as Alan Corr cheerfully told him later, it could have pushed the boat all the way to Arklow in half the time.

But he was enchanted by this strange new world, and the camaraderie of the sailing community as expressed in Poolbeg. He made a tentative foray into the club's Wednesday night racing, and was even more strongly hooked. But even though those Wednesday club races in the inner reaches of Dublin Bay were such fun that from time to time he still returns to race with his old clubmates at Poolbeg, he knew that his ambitions would dictate a move into a larger boat, and the bigger world of Dublin Bay sailing. So when the next Dublin Boat Show came along, he went to it and ended up buying a Bavaria 30 from Paddy Boyd, who was marketing Bavarias in the interval between being Secretary General of the Irish Sailing Association, and Executive Director of Sail Canada.

Paddy Boyd wised him up to the Dun Laoghaire sailing scene, and which club he might find the most congenial while being suited to his ambitions. For Liam Coyne was discovering offshore racing, and particularly the annual programme of the Irish Sea Offshore Racing Association. He liked everything about ISORA, the friendships, the willingness to help and encourage newcomers, and the pleasant sense of a mildly international flavour between the English, Welsh and Irish contingents.

One of his fondest memories is of taking his Bavaria 30 across to North Wales for the annual Pwllheli-Howth race which traditionally rounds out the season, and is often blessed with Indian summer weather. As he headed away from Dublin Bay, he suddenly realised it was the first time he had ever left Ireland under his own command. All previous exits had been on scheduled ships or planes. It was a very special moment.

Yet while he treasures the memory of such special moments, it wouldn't be Liam Coyne if he wasn't moving on. He'd relocated his base of operations to the bigger scene of the National Yacht Club and Dun Laoghaire, and developed his taste for double-handed offshore racing and its link to a group whose only common denominator seemed to be that many of them shared an enthusiasm for racing vintage Fireballs in Dun Laoghaire harbour in the winter.

But in the summer, keelboat offshore racing with just two on board was increasingly their main line, and he was soon on terms of friendship with the likes of Brian Flahive, Barry Hurley and others, while the double-handed class in events like the Dun Laoghaire-Dingle, the Round Ireland, and the Fastnet itself were coming up on the radar.

The newly-acquired First 36.7 which became Lula Belle greatly broadened the scope of Liam Coyne's offshore racing. Photo: W M Nixon

The First 36.7 is of a useful size to be a very pleasant family cruiser, but Lula Belle has been a multi-purpose boat since Liam Coyne bought her, with the emphasis on double-handed offshore racing, and the longer the course, the better. Photo: W M Nixon

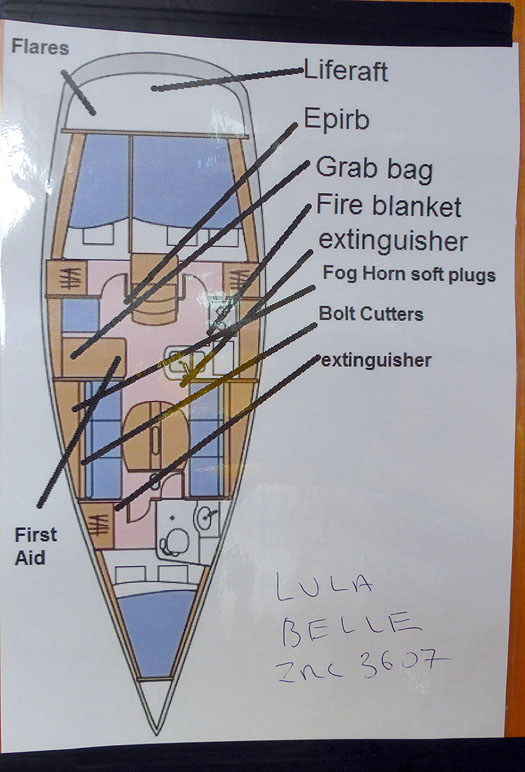

Lula Belle's layout - the accommodation of a cruiser/racer with extras installed for serious offshore racing, but for proper cruising they'd also be required. Photo: W M Nixon

Having made his mark offshore partnered with Brian Flahive on the Bavaria, he very quickly moved up to the almost-new First 36.7 Baily, bought from Tom Fitzpatrick of Howth. His name of Lula Belle for the boat was inspired by a recently-deceased aunt who had invariably addressed all of his sisters as "Lula Belle" when requesting something like a cup of tea. It's certainly a distinctive name, and it was beginning to feature regularly in short-handed and fully-crewed offshore racing reports when Ireland fell off the economic cliff around 2007.

The tyre business was hit particularly hard, for they're items whose replacement people can try to avoid by shifting used tyres around on and between vehicles to get the last piece of tread usable. But fortunately, one of his key contracts was in the heavy industrial area, where they use tyres so big your everyday motorist has no notion of them, yet legal safety working requirements dictate their regular replacement.

Despite this, at one stage his fine workforce of 48 had become effectively just two, while three of the five depots were closed. "I can tell you" he says, "there were times when we were glad enough the wife had kept her teaching job". And they were raising a family, eventually with three kids with a much-loved holiday home at Enniscrone in southwest Sligo. Then too he had this 36ft racing boat too. Yet all his fine assets and the value of the family home in Dublin had effectively been slashed by at least 50% and often more.

But somehow he kept going, and he even continued to race offshore. By this time one of the leading figures in the Irish short-handed sailing scene, Barry Hurley, had moved to Malta, and when he was recruiting crew for a friend with a Grand Soleil 40 for the annual 620-miles Middle Sea Race from Valetta in late October, he filled four berths with able-bodied crew from Dublin including Barry Flahive and Liam Coyne.

That race brought something of another epiphany to match that moment of pure joy at realizing he was skippering his own boat out of Irish waters for the first time. They'd come through the Straits of Messina eastward of Sicily, and next turn of the course was the volcanic island of Stromboli. It was a blissfully warm summer's night, and Liam was at the helm in just shorts and shirt, enjoying the sail and revelling in the race.

Stormboli was gently erupting just enough to show it was there, and ideal to be a mark of the course. "I'll tell you," says Liam, "it was a very long way indeed from your usual October night in Swinford". The magic of the moment reinforced his ambition to see his business through the recession and out the other side, which he has now achieved with busy depots in Navan and Dublin, and staff back above the twenty mark. Yet oddly enough, it also reinforced a shared ambition with Brian Flahive to do the four-yearly Seven Stars Round Britain & Ireland Race, when conditions up in the northern seas off Shetland and across towards the Faroes can often make an October night in Swinford seem like the balmy Mediterranean by comparison.

But the idea just wouldn't go away, and they put down their names for the 2014 race. With the economy coming out of intensive care and two good managers running his two depots and the three kids though the very young stage, Liam Coyne felt he could take off the time for this major challenge. But even so it was done without any form of shore management support, and in fact he managed to mix it with some family cruising – to which the boat is surprisingly well suited – by taking his young son Billy (10) and daughter Katie (8) along with him for a leisurely delivery to Cowes by way of many of the choice and picturesque ports along the south coast of England, where his wife and the youngest child joined the party to see them off.

That was in the last of the summer. By the time the starting date was upon them, it was as if a giant and malevolent switch had been activated. The weather was horrible, and even when Bertha had finally grumbled along on her way, it was anticipated that the rush of bitterly cold north winds she'd drag down from the Arctic in her wake would be every bit as unpleasant.

Then came the complete reversal of the course, and the postponement of the start. For a crew who were being their own shore managers and technical support team, it added a last minute mountain of research work on the shape the weather might be when they finally got away, and all the mental strains of waiting overnight for the start. As the lowest-rated boat in the entire fleet, they may have had the consolation of knowing that if they finished with just one boat behind them then they wouldn't be last on corrected time. But by being the low-rater, they would probably finish so long after everyone else that any general celebration would be long over.

That said, when a double-handed team have already successfully bonded, they're better at withstanding the strain of an enforced wait for a delayed start than a larger crew. I can remember only too well when the RORC Cowes to Cork race of 1974 was postponed for ten hours by the then RORC Secretary Mary Pera. A Force 10 sou'wester was making the Needles Channel a complete maelstrom on the spring ebb, but it was forecast soon to ease, so we were to be sent off on the evening ebb.

To get through the wait, it seemed best to stay well away from the boat and have a quiet day if at all possible. But aboard the 47-footer on which I was sailing, there were action men who decided it was time for a party lunch. So although I slunk away alone up the back streets of Cowes (Kensington-on-Sea it was not), and found a little café where the owners were persuaded to provide lunch of boiled potatoes and steamed fish instead of the usual nausea-inducing fish'n'chips, back on the waterfront others meanwhile had different ideas. A massive former rugby international in our crew decided the best way to pass the time was a champagne reception in one of the Cowes clubs followed by a bibulous lunch, and he persuaded several shipmates to join him, though they were circumspect in their consumption while he went at it as though it would be the last festive lunch in his life.

When we finally got racing the wind had indeed eased, though things were still rough enough in the Needles Channel, where we slammed into a head sea with such vigour that the Brookes & Gatehouse speedo impellor – normally a particularly stiff-to-move bit of equipment – was shot into its hull housing so totally we assumed it had broken entirely. It took a few seconds to realize what had happened, and it worked again happily enough once it had been pushed back into working position with the usual robust heave.

However, our mighty rugby forward was not so happy. He was not a happy budgie at all. The news is that, though you may be battering along noisily but successfully with endless bangs and squeaks and groans of one sort or another, when an international rugby forward of classic size gets massively seasick, a new dimension enters the sound and vibration scene - it's as if the entire boat is shuddering from end to end.

But enough of that. In Cowes on the morning of Monday August 11th 2014, it was still blowing old boots from the west , but they tore away downwind like there was no tomorrow. And for some, as far as racing was concerned, there wasn't. Any tomorrow, that is. There were several overnight retrials that set out to be temporary but became permanent. Aboard Lula Belle, however, they were still going strong, but after recording that gust from astern of 42.5 knots (which meant it was pushing 50), the masthead broccoli decided it had had enough, and made its exit.

Some time long before the race, Liam had decided he'd ensure the minimum use of power by having a LED tricolour masthead light, and a technician had been sent aloft to fit it. But that first night, it took off on its own, but taking much else with it, and leaving a beautifully clean masthead, but damn all information for those down below other than a Windex with an increasing tendency to jam.

And already the sails were suffering, for although their gybes were hectic enough, they didn't have to worry about check-stays or runners. But the downside of that was the well-raked spreaders, which helped support the mast in the absence of any aft support rigging other than the standing backstay. The inevitably prominent upper spreader-ends were chafing holes in the mainsail which, despite repairs, were enormous by the finish.

Speed at sea – Brian Flahive on the wheel as Lula Belle puts in the kind of sailing which knocked off 200 miles a day. Photo: Liam Coyne

But they blasted on, roaring on a reach up through the North Sea with Lula Belle doing mighty well, as the more extreme boats such as their closest rival, the Figaro II Rare, weren't quite getting the conditions to enable them to fly, whereas old Lula Belle was knocking off 200 miles in every 24 and saving her time very nicely.

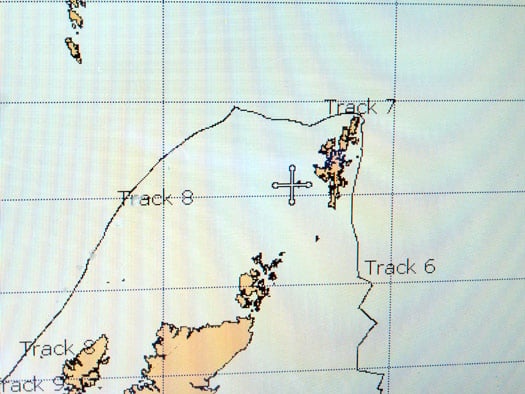

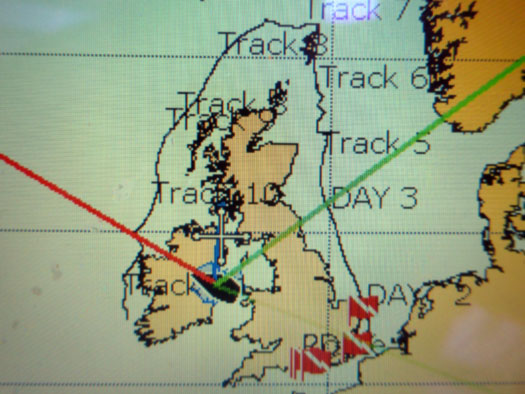

North of the English/Scottish border, the strong winds drew ahead. The forecast, however, was for westerlies, so some boats in front laid markedly to the westward looking for them. But Coyne and Flahive sailed a canny race. What they knew of the weather maps suggested very slow-moving and messy weather systems with lots of wind. And from ahead. They reckoned the prospect of westerlies was just too good to be true. And they were right. On the entire leg up to Muckle Flugga, the most northerly turn, they never strayed more than five or six miles from the rhumb line, and thus they sailed the absolute minimum distance, albeit in very anti-social conditions, to get to the big turn.

The sunless sea, with Lula Belle getting past Muckle Flugga on Shetland, the northerly turning point of the RB & I Race, and the sky promising plenty of wind Photo: Liam Coyne

The win move. Although Lula Belle had taken a conservative route northward, once they'd rounded Muckle Flugga they took a flyer to try to get on the favoured side of a slow-moving yet very intense low. The plan succeeded, but they'd to go almost halfway to the Faroes for it to work. Photo: W M Nixon

By this time the faster boats had got back into a substantial lead, but here the situation suited the Irish duo. Those in front went battering and tacking into a fierce sou'wester, trying to get nearer the next turn at St Kilda. But the Irish boat's cunning scheme was to slug directly westward once they'd rounded Muckle Flugga, and not tack until they'd some real prospect of being in the harsh northerlies which they knew to be somewhere out beyond the very slow-moving low pressure area.

Thus they ended up midway between the Shetlands and Orkney to the southeast, and the Faroes to the northwest. As Liam Coyne drily puts it: "When you take a flyer like this and it works, it isn't a flyer any more – on the contrary, it's the only way". What they didn't know was that the boats trying to batter their way past the Outer Hebrides and down towards St Kilda had taken such a pasting that their immediate rival Rare had made a pit stop to rest up in the Shetlands, and others dropped out "for a while" only to find it had become a matter of retiring from the race.

But Lula Belle, having cast the dice to go west, had no option but to keep going, as she was nearly 50 miles west of the Rhumb Line, and more a day's fast sailing from any shelter. By this time, the Scottish forecasters had up-graded their gale warnings to severe storm Force 10. But thanks to their pluck in going west, Coyne and Flahive were up towards the northwest corner of the low, whereas the opposition were down in the southeast quadrant where the winds are usually significantly stronger.

Nevertheless at the change of the watch they shortened sail to the three-reefed main and the storm jib, even though the wind had fallen right away. Brian went off watch and then returned on deck after some sleep to find Liam had become becalmed, and had been so for some time. The centre of the low was passing straight over them. Now it was only a matter of time before the new wind came out of the north.

When it did it was nasty and cold, and the sea became diabolically rough and confused. But it was a fair wind, and they made on as best they could through the short northern night to close in on St Kilda. It was sunrise when they went past that lonely sentinel, and for once there was briefly sunshine to prove it, but it was watery bad weather sunshine as they settled in for the long haul to Ireland.

A great fair wind at last, but it was so very very cold despite some sunshine. Photo: Liam Coyne

Early morning as they pass St Kilda, with Lula Belle well placed in the race and her closest but higher-rated rivals astern. Photo: Iiam Coyne

By this stage the boat was very much their home, and they were both in good spirits. Despite the expectation of being in race mode for at least ten days and probably much more, they hadn't anything too much in the way of special easy-made instant food. When asked who had organized their stores and how they had been procured, Liam responded: "I just went to Tesco before the race, and filled her up. It's very easy when you've only two. I've had to do the stores for the boat with a crew of eight, and it's a pain in the neck".

Getting an omelette just right is tricky at the best of times, yet this masterpiece was created aboard Lula Belle off the coast of Donegal in 30 knots of wind. Photo: Liam Coyne

As for living aboard, they used the two aft cabins for sleeping, with hot bunking dictated by which was the weather side. In cruising mode, the First 36.7 is a very comfortable boat, but in racing things tend to get put behind the lee-cloth on the weather settee berth in the saloon, for the fact is the boat is designed to be raced with a crew of 7 or 8, and she tends to be a bit tender without six bodies on the weather rail.

Post-return temporary disorder in Lula Belle's saloon on her arrival back in Dun Laoghaire after sailing nearly 3000 miles in all since she'd last been in her home port. Though Brian (left) and Liam used the aft cabins for the short off-watch periods of sleep, the lee cloths on the settee berths were kept up to provide ready stowage for loose gear, preferably on the weather side. Photo: W M Nixon

Having the toilet on the fore-and-aft axis is very convenient at sea. And having an "extra-easy-cleaned" compartment is a real boon for hygienc. As for the funnel and hose, that's essential in a men-only boat in racing mode. Photo: W M Nixon

To my mind, one of the best things about the accommodation is the heads (toilet if you prefer). Some folk might think the compartment is too compact, but the loo is aligned fore and aft, so there simply isn't the room to fall about when using it. With the fore and aft alignment, security and comfort is guaranteed at those special private moments. It should be a law of yacht design that any boat which is going to be taken further than half a mile offshore is designed with a fore and aft loo.

Such thoughts would not have been forefront in the minds of Lula Belle's crew as they set the A3 spinnaker for the long run to Black Rock off the Mayo coast. Inexplicably, and as evidence of their stretched shoreside management support arrangements, they'd failed to bring along a new Code Zero spinnaker from sailmaker Des McWilliam. They'd gone for it despite it putting three extra notches on their rating, but it was nowhere to be found. After the race, it was discovered among a pile of 20 sails in Liam's Dublin office. But out in the lonely ocean southwest of St Kilda, it wasn't there when it was needed.

Yet it was soon needed even more. The smaller sail that was put up simply disintegrated after a brief period of use. It was inexplicable, but reasons weren't important just then, they were now down to just two spinnakers, and a very long way to go downwind to the finish.

So they nervously got out the A4, and soon it was up and drawing and Lula Belle was back in business, sailing fast for Ireland. Liam went below for a much-needed kip, and a sudden squall over-powered the boat. By the time he got back on deck she'd broached completely and the sail was shredded. They were down to just one spinnaker, and one in very dodgy condition at that. To add to their joys, in a crash gybe the mainsheet carriage disintegrated and they'd "ball bearings, it seemed like hundreds of them, all over the place...."

So there they'd been, passing St Kilda and knowing that, despite the lack of sailing instruments, they couldn't have done the leg from Shetland any better, and more importantly knowing from Yellowbrick that Rare was now well astern. Yet here they were now, only a few hours on the way, and they were down to one spinnaker and a jury-rigged mainsheet arrangement and a long way to go and the weather starting to suit Rare. Could it get any worse?

It did. Approaching the Blaskets, as usual the ship's batteries were draining with unreasonable speed. But the engine, when called upon, was dead. Dead as a dodo. It turned over but just wouldn't start. They knew that in very short order they'd be even further cut off from the outside world than they were already, with no chart plotter and without even the comfort of Yellowbrick to tell them how they stood in relation to the opposition. No autohelm whatever, either. And they'd 495 miles still to sail.

Moment of truth. The chart plotter's power dies just north of the Blaskets, the most westerly point of the 1802-mile course. Photo: W M Nixon

Getting on with it. Just south of the Blaskets, Brian goes aloft to try and clear the constantly-jamming Windex. Photo: W M Nixon

So they picked themeselves up, dusted themselves off, and started all over again. Brian went aloft to the waving masthead to free the Windex, which was in its jamming mood. Then progress was good heading down towards the Isle of Scilly. But even so, midway across, alone at the helm and steering and steering and steering, Liam admits to a very low moment.

They were now almost midway between Cowes and Dun Laoghaire, So he thought to himself: Why not just turn to port and head for home? Head for that comfortable NG34 berth in Dun Laoghaire marina, instead of struggling on with sails which were bound to shred even further, and leave them eventually straggling across the line completely dog last and with everything to fix, and then they'd have to turn round and plug into the early Autumn gales all the way back round Land's End to Dun Laoghaire?

And what then? he thought. Well, then in four years times we'll have to do the damned thing all over again. All, all, over again. So we'll just finish the bloody thing now, and get the T-Shirt, and that will be that regardless of how far we're placed behind everyone else, and good riddance to it all.

Welcome back. Knowing of Lula Belle's engine-less plight, the Cowes harbourmaster made sure they were brought into their Berth of Honour in style. Photo: Liam Coyne

So they stuck at it, they nursed the boat through the shipping separation zones at the Scillies without the spinnaker up because they knew the multiple gybing would destroy it, then as Rare didn't get past them until this stage, they knew that after such a long race she'd need to be 22 hours ahead at the finish and that was surely impossible. They were very much in with a shout of being better than last, so they nursed that mangled old spinnaker right up the English Channel (Mother Flahive's emergency sewing machine had done some marvellous repairs), and maybe the spreader ends were now showing out through the mainsail again, but what the hell, they got in round St Catherine's point and shaped their way back into the eastern Solent and on up to Cowes, and didn't Rare's crew and various bigwigs come out to tow them into port and confirm to them that they had indeed been there, they'd seen it, they'd done it, they'd won it., and now they could get the T-shirt.

Been there, seen it, done it, won it, got the T-shirt.....Liam Coyne back at the bar of the National YC five days after winning the two-handed division and two RORC classes in the 1802-mile Seven Stars Round Britain & Ireland Race 2014, and with his boat Lula Belle safely returned to her home port of Dun Laoghaire. Photo: W M Nixon