#classicboat – In the summer of 2014, the RNLI in Crosshaven received an unexpected cheque from an unusual source. As ever with lifeboat fund-raising, it was very welcome. But it's not every day you get €1500 out of the blue from a high fashion magazine like Vogue Netherlands. W M Nixon unravels the tale of how this came about, and ponders the various challenges facing the enthusiasts who try to keep classic boats in full sailing commission.

Once upon a time, on a pure early summer day of clear sunshine in Connemara, the demands of the day job caused us to head up the driveway of one of the pleasantest country house hotels in all Connacht. But the bright mood of the morning was soon dispelled by finding the place full of bad tempered if beautiful people from Italy.

It turned out they were the complete creative team – photographers, models, directors, editors and all – from a leading Milan fashion magazine. They were in Ireland for a long-planned and lengthy photo-shoot of the coming season's trendy tweeds. They'd reckoned the Irish climate would guarantee they'd be up to their ears in ideal conditions to provide moody shots of even moodier models in ultra-fashionable tweeds on an extraordinarily moody bog with unbelievably moody Irish mountains beyond, the whole thing recorded under an uber-moody grey Irish sky.

But for day after day, the sun had shone from a cloudless sky, the breezes blew only very gently from a blue Atlantic, the fabulous range of the Twelve Bens could quite reasonably have been re-named the Twelve Benigns, while the great swathes of bog glowed in friendliness in the sun. Moodiness was out. All was sweetness and light. And the forecast was for more to come.

So after another day of screaming frustration, they upped and left, screeching that they could find more suitable conditions back home, just down the road in the Valley of the Po. Doubtless they could. But back in Connemara everyone simply relaxed and enjoyed it, for the Italians' bill had been paid in full, they maybe could even re-let some of the rooms in the hotel in the few days remaining of the booking, and sure wasn't the weather just wonderful anyway, and had we ever seen the garden looking so well?

If you think fashion people are out on a limb in relation to the rest of us, take time to reflect that for most of humanity, boat people are odd too. Even with the newest craft, we still think of them as living beings, whereas the rest of the world thinks that, regardless of their age, they're no more than vehicles, and uncomfortable, awkward, dangerous and expensive vehicles at that.

Roundstone in Connemara on a gentle day with a sublime view towards the Twelve Bens in the evening sunshine – totally unsuitable conditions for a mood-laden fashion shoot. Photo: W M Nixon

So when you get some sailing person whose pulse is quickened only by classic or traditional boats – anything unusual so long as it is full of character, and preferably old - then you get someone who scores a double negative with the ordinary run of boat-loathing humanity.

And though high fashion may be comprehensible to a larger proportion of mankind than is enthusiasm for old boats, nevertheless it too is still a rather peculiar or at least very specialist interest with which to dominate one's life.

Thus it's just possible that when high fashion and dedicated classic boat fans link up, an unexpected bond can be formed. Certainly it seems to have happened when Vogue Netherlands got together in Crosshaven during the summer for a photo-shoot with Darryl Hughes' superbly-restored 1937 Tyrrell-built 43ft ketch Maybird.

And the successful outcome of it all, with a useful cheque being presented to Crosshaven RNLI afterwards, was a reminder that while boat restoration projects can indeed be brought to a successful conclusion, once the job is done, you then have to move on to the next stage of finding imaginative and useful things for the boat to do, as there's nothing worse for the wellbeing of any boat than doing nothing.

After two good day's work afloat out of Crosshaven, a cheque for €1500 is handed over by Zoe Rosielle of Vogue Netherlands to Patsy Fegan, RNLI Deputy Launch Officer Crosshaven, with Shore Crewmember Robbie O'Riordan in support. Also in the picture are the rest of the Vogue Netherlands team, with three of Maybird's crew – Pat Barrett, Marie Keohane, and Darryl Hughes – top left, while fourth crewmember Joeleen Cronin took this photo

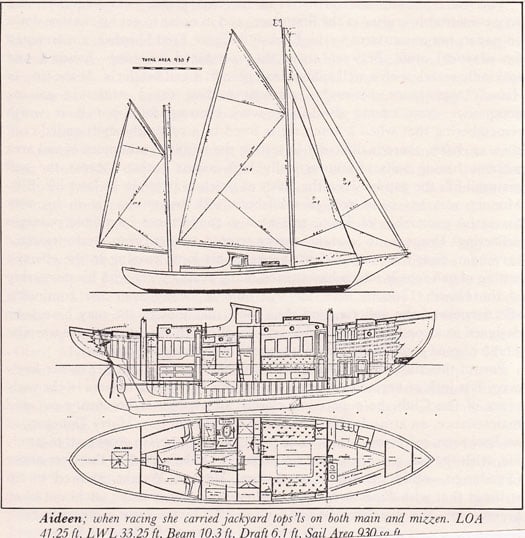

The story of Maybird has been told in snippets here before. She's a very near sister of the 16-ton ketch Aideen which was built by Jack Tyrrell of Arklow in 1934 for Billy Mooney, who in those days was Howth-based, but he later became a leading figure in Dun Laoghaire. Aideen was built to a Fred Shepherd design, but it's said that Shepherd had only been brought in to put manners on numerous very detailed drawings by Billy Mooney himself, including the layout – unusual at the time - of a centre cockpit.

Very conservatively rigged as a gaff ketch, Aideen was no slouch – she won her class in the 1947 Fastnet Race. Soon after, she was sold to Canada, where she was last heard of in 1974. Mooney claimed he'd to sell her because he could no longer afford to buy his crew dinner every time they won a race, and they were winning too often. That was a very Billy Mooney kind of remark, but certainly he almost immediately down-sized to the excellent little 6-ton John Kearney Bermudan yawl Evora of 1936 vintage, and with her he continued winning offshore until, with his retirement from work, he also swallowed the deep sea anchor and took up Dragon racing in Dublin Bay.

Meanwhile, during the mid 1930s an admirer of Aideen had been a keen sailing man originally from Cork, one W C W Hawkes, an officer in the Indian Army who commissioned Maybird, a near sister-ship of Aideen, from the Fred Shepherd-Jack Tyrrell team in 1937. Hawkes retired from India in the late 1930s to live in Restronguet on Falmouth Harbour in southwest England, but he was to have little enough use of Maybird with the intervention of World War II from 1939 to 1945, and his death in the late 1940s.

The first-born. Billy Mooney's Aideen was built by Tyrrell's of Arklow in 1934. Her younger sister Maybird, built in 1937, had a slightly longer canoe stern. Maybird's modern accommodation layout is also different, with the galley moved aft to the starboard side at the foot of the companionway

Maybird under her Bermudan rig in the late 1950s. Her restoration has included this rig's replacement by the original gaff configuration for the mainsail.

Subsequently, the 43ft ketch led a varied career, acquiring a Bermudan rig and an RORC rating for racing, and then in 1972 she was sailed out to New Zealand. Darryl Hughes came upon her there in 1990, and was smitten. Quite why some boats speak so eloquently to some people at certain times is sometimes difficult enough to understand, but the great project he has since completed with Maybird suggests that in this case it was the one very special boat for one very special person, and at just the right time.

He comes from a community in North Wales where there was no local tradition of industry or high-powered commerce, yet education at the local grammar school and a degree from Manchester University saw him moving into international companies, and by his thirties he was a rising star in general management in global organisations with a later emphasis on marine electronics.

This in turn fostered his interest in sailing, and he was learning the ropes with his own Nicholson 32 when a working spell in New Zealand led to his first sight of Maybird in the Bay of Islands. By 2007, with an early and well-funded retirement beckoning, he had her shipped back to England with a restoration in mind.

But the quotes he had for the job from established yards were horrendous, so he decided to do it himself as his own Project Manager. Sensibly, it was done in the heart of the English marine industry, where he could call on a diversity of talents to make progress with this project, which was soon well under way in Southampton in a temporary shed he'd created with tarps over a proper scaffolding structure.

The owner-managed restoration project on Maybird under way in the temporary shed in Southampton. Photo: Darryl Hughes

Mission accomplished – the restored Maybird emerges from the project workshop. Photo: Darryl Hughes

His long experience in international industry stood well to him, for the work went steadily ahead, and after two years the restored Maybird emerged as good as new, in fact better. And the project was completed for around a quarter of a million pounds sterling, about half of the most reasonable quote he'd received from the established yacht restoration yards.

For many people, such a restoration would be enough in itself, but Darryl Hughes showed his calibre by progressing on to keep Maybird as active as possible. She was raced in the classics in the 2011 Fastnet, and finished in a slightly better time than that recorded by Aideen in 1947. As well, she has been cruising extensively, sometimes on a semi-commercial charter basis, while also taking part in classic yacht regattas.

When it all becomes worthwhile. The restored Maybird sails again, re-rigged as a gaff ketch to the original design.......

.....and she turns in an encouraging performance, with a better time in the Fastnet Race of 2011 than Aideen had in the Fastnet of 1947.

An underlying theme has been his growing interest in Ireland and things Irish, thus he has based the boat for lengthy periods in Crosshaven while researching the history of the Hawkes family in Cork and in Cork Harbour sailing. But as well he has extensively cruised the Irish coast, and with his developing interest in literature he has twice taken a full part in the Yeats Summer School in Sligo in late July. The new pontoon just below the bridge in Sligo port might have been installed for Maybird's convenience, but Darryl Hughes is still the only person who is known to have sailed to the Yeats School as a matter of course.

In 2011, Maybird returns to her birthplace of Arklow, where she was built in 1937. Photo: W M Nixon

Immaculate workmanship. The beautiful restoration of Maybird's deck and coachroof, seen in Arklow in 2011, contrasts with the rough and ready beer keg pressed into use to aid boarding. Photo: W M Nixon

Currently, Maybird is based in friendly Poolbeg Marina in Dublin Port, and her owner has spread his wings even further with a course of study in Trinity College, while living on the boat and pondering the production of the required 15,000-word dissertation on Irish writing. Last winter, however, was spent in the congenial surroundings of the Salve Marina in Crosshaven, and thanks to that there was the involvement with Vogue Netherlands – we let Darryl take up the story:

"Vogue Netherlands wanted to organise a fashion shoot in SW Ireland, and their location scout came across Maybird wintering at Crosshaven in Cork harbour back in February 2014. I agreed that they could use her as long as they made a contribution to the Crosshaven RNLI station, and the shoot took place in early June over two days.

The entire Vogue contingent consisted of eight people - three models, photographer, photographer's assistant, make-up/hair stylist, wardrobe assistant and overall fashion director, together with three huge suitcases of clothes for the models plus extra camera gear, lenses etc etc. To sail Maybird we had a crew of three plus myself, the other sailors being Pat Barrett, Marie Keohane, and Joeleen Cronin, the daughter of the house in Cronin's pub. As you can imagine, my major concern was the safety of all aboard as the majority were not sailors.

We met the day before onboard and worked out that Maybird's aft cabin would do as the changing area for the models and the huge suitcases were manhandled down the companionway and through the galley. The aft cabin was then transformed into a Vogue changing room/hairdresser's salon. The plethora of laptops, lenses and spare cameras plus the film banks – yes, film, not all that digital malarkey I'm pleased to say- were stowed in the saloon. The saloon became the studio, but we had access to all of Maybird's chart table and instruments if required. Fortunately, all of the chart-table electronics are duplicated in the doghouse, which also has the 15" plotter screen.

The aft cabin, luxurious by the standards of 1937, made for a rather cramped changing room/hairdressers salon during the Vogue Netherlands photoshoot. Photo: W M Nixon

The galley and the chart-table together amidships at the foot of the companionway may seem a tight fit to modern sailors, but it would have seemed the height of comfort to cruising folk in the 1930s. Photo: W M Nixon

Once the stowage was sorted, we agreed that unless people were required on deck they stayed below. Everybody wore life-jackets and the only people that were allowed to take them off were the three models when the camera was rolling. Once the camera was silent the models donned their life-jackets again. We had a support RIB so that the cameraman could take pictures of Maybird sailing, so to an extent we had our own lifeboat with us, but my job was to keep all twelve "crew" on board.

We were blessed with gentle sailing conditions for the first day - wind max F3. The director wanted all Maybird's sails hoisted, and so we agreed set courses to sail. The crew set Maybird up, we chose courses that we could hold for as long a time as depth/traffic/hazards allowed, and then the photographer got to work with the models. We had an excellent rapport with the photographer, who understood that the skipper has the final say, and would stop shooting when we made the call "30 seconds to tack". Each of our legs or boards had to be agreed with the photographer in terms of where the sun was, the effect of shadows, background etc..

One of the models was starting to experience the early stages of sea-sickness as we approached the harbour entrance abeam of Roche's Point lighthouse, so we headed back inshore. Recovery was more or less instantaneous when back in flattish water.

Given the largely clement conditions we were out for some seven hours on the first day. But Day 2 was different. Wind was up to F5 gusting F6 and the sky overcast. The sea state was no longer smooth but more moderate to lumpy. I agreed with the director that we would go out, but we would not put up the mainsail - we would sail with jib, staysail and mizzen. I just wanted to keep things as simple as possible from a sail-handling viewpoint.

The cameraman wore his safety harness as well as his lifejacket as he was leaning over the bowsprit and over guardrails to take many of the shots that day, so I made sure he was clipped on. We agreed the models would not lean over the guardrails or do any poses that could lead to them falling off the boat. For this day, we were only on the water for some three hours.

Interestingly, the only pictures from Day 2 used were a black and white one with the female model standing on the foredeck. The sky really was nasty. No Photoshopping used there!

Despite Maybird's complexity in terms of numbers of sails and ropes, as she has a long keel she will sail on her own and hold her course when the sails are balanced so it was easy for her sailing crew to set her up and then crouch down out of the cameras way whilst the models did their stuff.

Both the photographer and his assistant were sailors back in the Netherlands, so that helped a great deal. The Maybird crew of four for one day, three on the other, really kept an eagle eye on the Vogue crew in terms of safety - that was the challenge, not sailing the boat. We tacked rather than gybed and as I say, when the wind did pick up, we sailed without the main - one of the great advantages of the ketch rig.

We managed to stay out of trouble, so our only dealings with the Crosshaven RNLI was to hand over a cheque to them".

That was only part of the good work done by Maybird in 2014. She was signed on to play a key role in an Irish Coastguard exercise in Dungarvan Bay later in the summer. Then once again the skipper's participation in the Yeats Summer School in Sligo resulted in a round Ireland cruise, with bits of Scotland thrown into the mix. And now she's a study centre in Dublin, helping to absorb the multi-facetted culture of our unique city. Truly, a busy ship is a happy ship.

Maybird as seen from the S&R helicopter during an exercise in Dungarvan Bay. Photo courtesy Irish Coastguard.