#dday – More than three generations have come of age since the end of World War II. For most people nowadays, it is remote and sometimes incomprehensible history, captured only in films which - it is assumed - exaggerate the horror of it all.

It certainly suggests a world which could not be more different from that which we enjoy today. With all modern life's problems, we still have a freedom of movement and a choice of activities which were unknown for those on active service during the six years of war. Yet among those who volunteered – including many Irishmen and women – there was a clearcut feeling that a job needed to be done. But once it was done, then peacetime life could be enjoyed with extra zest.

This week, senior Dun Laoghaire sailing man Mickey d'Alton was awarded France's Legion d'Honneur and America's Distinguished Service Award in celebration and commemoration of his personal contribution to the success of D-Day in 1944. W M Nixon reflects on some very special and personal sailing stories.

You could tell there was something different about these men. From the mid 1940s onwards, there were these Irish sailing enthusiasts whose pleasure in our sport had its own special zest. They lived for the moment, they lived to sail the sea. The amount of sailing they did, and their huge enjoyment of it, was a wonder to behold.

For these were the men who had seen active service at sea in World War II from 1939 to 1945. Ireland had stayed neutral. But there were those who, while they may well have supported this policy of neutrality for Ireland, nevertheless felt the need to get personally involved in the war against Nazi Germany. Mostly, they'd joined the British army. Then there were those who sought the opportunity to learn flying while they were at it, and joined the Royal Air Force. But from within Ireland's sailing community, there were those who felt the only way to go to battle was in the war at sea.

Yet during the war itself, when they came home on leave to neutral Ireland, they went sailing whenever possible, and would bring like-minded British sailing enthusiasts with them to savour the relaxation of being able to go afloat simply for pleasure and freedom of movement, rather than for sudden sharp bursts of activity trying to kill other seafarers between the long periods of acute boredom at sea or in port waiting for action.

Until recently, despite the fact that Sweden, Switzerland and Spain stayed neutral throughout World War II without drawing obloquy upon themselves, Irish neutrality was a bone of contention even though Irish rebel forces had been at war with Britain only eighteen years earlier, and more recently there'd been Civil War in 1922 over the resulting peace treaty. Thus if Eamonn de Valera had led Ireland into World War II on either side, it would have resulted in another civil war, whereas the policy of careful neutrality, while not being totally hostile to the Allied cause against Germany, was in fact the best solution to a wellnigh intractable policy problem.

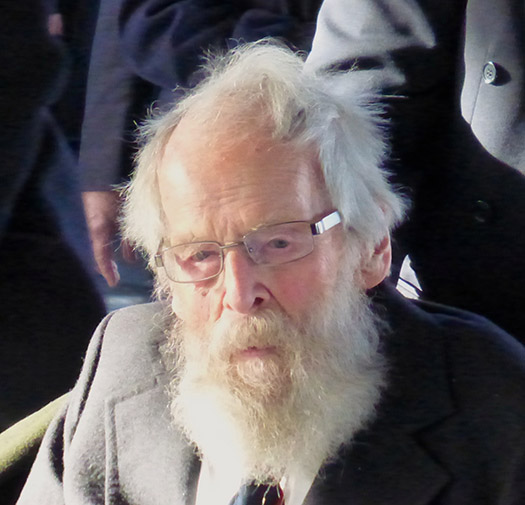

While historians may still argue about it today, a searchlight of pure common sense was shone into this sometimes murky corner in June 2014 on the 70th Anniversary of the Normandy Landings when D-Day veteran Mickey d'Alton – decorated this week with the Legion d'Honneur for his distinguished service in command of a Tank Landing Craft at Omaha Beach on June 7th 1944 - was interviewed about his experiences.

Mickey d'Alton in thoughtful mood aboard the French Naval Vessel Somme before receiving the Legion d'Honneur. Photo: W M Nixon

Mickey d'Alton in thoughtful mood aboard the French Naval Vessel Somme before receiving the Legion d'Honneur. Photo: W M Nixon

Almost as an afterthought, he was asked how he had felt - as an active combatant – about Irish neutrality. His typically clear-sighted analysis was like a breath of fresh air, a clarion call of sound reasoning. Mickey d'Alton thought that Irish neutrality had been the best possible way forward, indeed the only possible way. Apart from the very real risk of another civil war just 17 years after the previous one had ended with much bloodshed, if the government had decided to enter the new war, had they done so on the German side – which some wanted – then there would have been immediate invasion from Britain. But had they gone in on the Allied side, then the Allies would have been obliged to re-direct already limited resources to help in the defence of Ireland's long coastline and almost entirely unprotected countryside and cities.

Instead, Ireland went her own way, making no demands on the war resources of the allies, while still providing tens of thousands of able-bodied men and women to serve in the Allied forces, and moreover providing a haven in which they and their comrades could recuperate properly while on leave.

After the total horror of war was over, their greatest wish was to return to a life as normal as possible, and as quickly as possible. And after years of being restricted in their freedom of movement and in peril for much of the time from hostile sharers of the sea, their dearest wish was to sail just as much as humanly possible, and revel in the fact that they could do so without other vessels being seen as a direct threat.

Their desire to return to normal recreational sailing and everyday family life as quickly as possible meant that often they didn't talk of their wartime experiences, even among people who had strongly supported their motivation and actions. It seemed better to keep memories to yourself, for as Mickey d'Alton has said, his abiding memory is that war is an appalling waste of just about everything that it touches. As for another seafaring veteran, Norman Wilkinson of Howth who had also had "a good war", his attitude was that they hadn't fought in order to talk about it afterwards, he felt they'd fought to make the world safe for ordinary life and particularly for sailing, and as soon as hostilities were over, he did an impressive amount of sailing right up to his death at the age of 82.

In our comfortable modern world where we complain if a plane is half an hour late, we can scarcely imagine the bureaucratic moves and difficult travel such people had to complete in order to achieve their ambition of getting into the Royal Navy. Around Dublin, the word was that if you could get yourself the late-1930s equivalent of a Yachtmaster Certificate through Tom Walsh's mariners' courses, then that would give you access through the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve which had been set up to recruit experienced yachtsmen straight into the fast track to promotion.

Certainly that was the route taken by two Howth sailors I later got to know well, Norman Wilkinson and Ross Courtney. They both got the fair wind of the certificate from Tom Walsh in jig time, and on linking up across the water with the RNVR, Norman was immediately channeled into the commission line and went on to have distinguished if mysterious service among the Greek Isles in armed caiques. But for Ross, the medical was a set-back. Later I was to know him as one of the finest and most fearless close quarters helmsmen in all Ireland. But the naval medicos had found he was colour blind, which precluded him from any deck officer duties.

However, they told him to come back in a year or so, when demand would have risen to such an extent that his vision problems could well be set aside in order to avail of his obvious talents in seamanship. But Ross insisted that he wanted to start having a bash at Hitler just as soon as possible. It turned out the only job he could get on a warship was as a stoker, so throughout the duration Ross Courtney laboured in the acutely dangerous job of stoker, mostly on destroyers patrolling Transatlantic. And when the war was over and the Royal Naval Sailing Association was set up to provide yachts and sailing opportunities for former RN personnel, Leading Stoker Courtney was proposed for membership by an Admiral, and seconded by a Commodore.

While he and Norman Wilkinson had returned to Howth during leave to sail whenever possible, once peace broke out they returned to sailing with renewed enthusiasm. Before the war, Norman had been a keen helmsman in the nucleus of a National 18 class at Howth. But post-war, the 18s had gone. So as he was desperate to get regular racing, he finally bought into the only class likely to provide it locally, the already venerable Howth 17s. But suddenly there was a demand for 17s from returning servicemen. So he'd to go to Skerries where the 1898-built Howth 17 Leila had been more or less abandoned in a field, and in 1948 he finally closed the deal to buy her at the-then enormous price of 120 pounds.

Fifty years later, when the class was about to celebrate its Centenary, he was still sailing Leila with regular success. But there was no false sentimentality about Norman – when I asked him could he remember how he'd felt buying the boat he had grown to love all those fifty years earlier, he smilingly replied that he'd thought it was an awful lot of money to be paying for such an old boat, but he was desperate to get the opportunity to race regularly, and he continued to do so right up to his death.

As for Ross Courtney, he was already a Howth 17 star, but as soon as he could afford it he moved into offshore racers, and even in his late seventies this man who had been turned down for a commission because he was colour blind was still out-sailing and particularly out-helming all the opposition in his Sigma 41 Jabberwok.

The French Navy's logistics vessel Somme sailed to Dublin to provide the setting for the presentation of the Legion d'Honneur

The French Navy's logistics vessel Somme sailed to Dublin to provide the setting for the presentation of the Legion d'Honneur

Mickey d'Alton came from the other side of the bay, and was immersed in Dun Laoghaire sailing. He decided that Hitler was an "awful monster" who needed to be stopped as directly as possible, so by the age of 19 in 1940 he'd got himself into the RNVR and served in ships until it was over. But as he came with yacht and small boat sailing credentials, when the huge group of people who would be needed to pilot the armada of Tank Landing Craft right across the English Channel for the D-Day landings was being assembled, he perfectly fitted the job requirements. Thus his D-Day exploits became the defining experience of his lengthy war service, and it was this one and utterly exceptional action which saw him being celebrated on Monday with French Ambassador Jeanne Pierre Thebault pinning the Legion d'Honneur on Mickey d'Alton's 93-year-old breast.

People have asked why it was left until now to honour somebody who has clearly been a hero since 1944 and probably beyond. But it was only last year with the 70th Anniversary of D-Day that the French government made the decision to honour in this particular way anyone still alive in Ireland who qualified as a D-Day veteran.

For with the passage of time, the extraordinary achievement of the D-Day landings becomes ever more remarkable to contemplate, and the reality is that survivors such as Mickey d'Alton have an exceptional rarity value, not least because the fact that they have so cheerfully stayed alive for so long as active members of the community is a testament both to themselves and to the wonder of what they achieved.

As the ceremony was held in Dublin Port aboard the large French logistics vessel Somme – a gallant workhorse which recently did much to suppress the piracy problem off Somalia - there was something almost homely about the gathering, particularly as many of Mickey's sailing friends were there to wish him well. And as for the more military side of things, perhaps the most poignant although less formal moment on Monday was the presentation of the US Veterans' Distinguished Service Award to Mickey by John Shanahan of the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States

As John put it: "This was indeed an international allied effort, for here we had an Irish skipper piloting a British boat to invade France to fight the Germans with our American tanks – and Mickey didn't lose one of them." In fact, as anyone who watched Tom Cunliffe's excellent TV series "Six Boats Which Built Britain", the D-Day LCTS which made the invasion possible were an American invention. But whatever their origins, they needed skippers and navigators of the ability of Mickey d'Alton to complete their mission with success, though he remains haunted by the memory of those who failed to make it.

For although in some ways we may have sanitized the memory of D-Day through films of the quality of Saving Private Ryan simply because we assume that the unbelievably violent and rapid action must be exaggerated, when Mickey d'Alton was taken by his son Mark to see Saving Private Ryan, and then went for a quiet pint afterwards, when the son asked the father what he thought of Spielberg's movie, the answer was: "It was just like that at Omaha Beach. He got it exactly right".

It was a life-shaping experience, yet Mickey d'Alton seldom if ever talked of his wartime life during a postwar sailing career which has only eased off its extraordinary pace since he entered his nineties in 2010. Indeed, frequent shipmate Michael O'Rahilly, a former Dublin Bay SC Commodore, recalls that the only reference he ever heard in hundreds of miles of cruising with Mickey was when they were returning from the Faeroes in the Dublin Bay 24 in 1961.

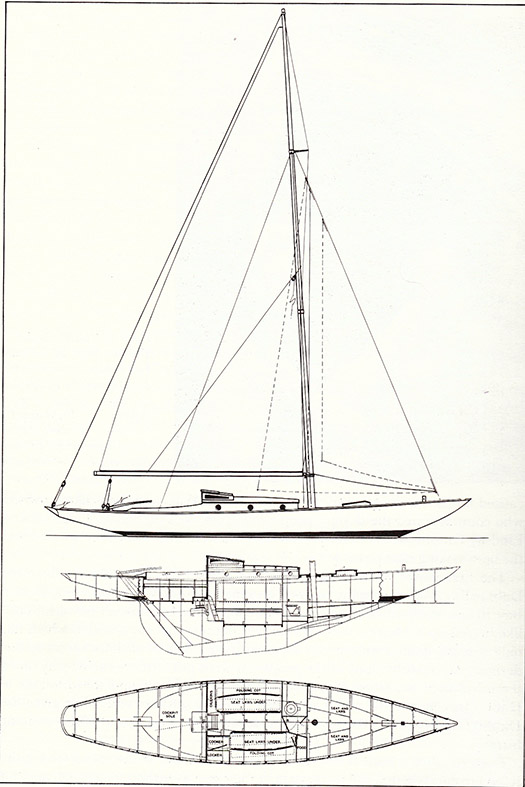

The Dublin Bay 24 might not be everyone's first choice for extended cruising, yet with Euphanzel Mickey d'Alton and Ninian Falkiner cruised to Norway, the Shetlands and St Kilda in 1956, and to the Faeroes in 1961. Both cruises were awarded the Irish Cruising Club premier trophy, the Faulkner Cup.

The Dublin Bay 24 might not be everyone's first choice for extended cruising, yet with Euphanzel Mickey d'Alton and Ninian Falkiner cruised to Norway, the Shetlands and St Kilda in 1956, and to the Faeroes in 1961. Both cruises were awarded the Irish Cruising Club premier trophy, the Faulkner Cup.

They'd come out of the south end of the Sound of Mull and were shaping their course towards the Sound of Jura as evening drew on, and as Oban was nearby, Michael suggested to Mickey that they might use Oban as an overnight anchorage. "I'd rather not" was the response, "I spent what seemed like a very long time in Oban on a training course during the war, and if I never see the place again it will be too soon".

With this award of the Legion d'Honneur, Mickey d'Alton will now be best known as an Irish hero of D-Day, which is perhaps as it should be. But the fact is that since the war ended, he has had an unrivalled sailing career – both inshore and offshore – of the highest achievements, while his life ashore has been one of abundant energy and many interests. Although a Chartered Quantity Surveyor, in his fifties he returned to college to study arbitration, and then went on to post graduate qualifications which have seen him negotiating and hearing cases at the highest international level.

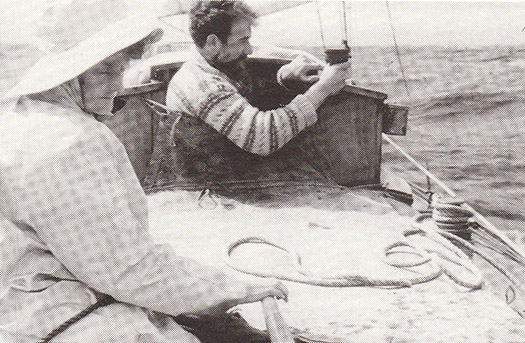

Mabel d'Alton at the helm as Michael O'Rahilly takes a bearing during the 1961 cruise to the Faeroes. Between them is the famous "D'Alton Cockpit Cover", which was fitted to Euphanzel on longer offshore passages as the Dublin Bay 24 did not have a self-draining cockpit. Photo: Michael d'Alton

Mabel d'Alton at the helm as Michael O'Rahilly takes a bearing during the 1961 cruise to the Faeroes. Between them is the famous "D'Alton Cockpit Cover", which was fitted to Euphanzel on longer offshore passages as the Dublin Bay 24 did not have a self-draining cockpit. Photo: Michael d'Alton

He married a kindred spirit in Mabel, and their two children Mark and Sonda bring the same lively intelligence to everything they do.

As to his sailing, although his proven success and perfectionism as a navigator in the era long before radio and electronics took over made him set the highest standards for his shipmates, he has always had the happy knack of teaming up with people whose abilities and resources neatly match his own skills, so much so that while he has owned a couple of boats, they have always been in partnership with kindred spirits.

His most renowned sailing achievements were as navigator and effectively sailing master with Ninian Falkiner, a pillar of the Dublin medical establishment who went on to become Commodore of the Royal Irish Yacht Club, with whom Mickey formed a very fruitful sailing partnership from 1944 until Ninian Falkiner's death in 1972.

Their best-known achievements were with the Dublin Bay 24 Euphanzel from 1948 until 1965. Gradually they built up their expectations with short cruises and offshore races, but in 1956 they hit the big time with a cruise from Dublin Bay through Scotland's Caledonian Canal to Norway, then across to the Shetland Islands following which – the weather being favourable – they simply sailed on across the open Atlantic in a sou'westerly direction for hundred of miles until they reached St Kilda, regarded as Ultima Thule in those days.

For this cruise, they were awarded the Irish Cruising Club's premier trophy, the Faulkner Cup. To put it in perspective, remember that as soon as Euphanzel got back to Dublin Bay, she returned to being a One Design boat in a Dun Laoghaire class raced regularly with the greatest possible vigour. Yet most summers they cruised as well, in 1961 going to the Faeroes with a special kayak-style cockpit cover developed by Mickey as the DB 24s didn't have a self-draining cockpit, and he reckoned they'd get their come-uppance one day. It duly happened on the way back – they were hit by a Force 9 but the d'Alton Cover worked a treat, whie their thoroughbred boat continued to make to windward in horrifying seas, with Mickey's navigation spot-on in almost zero visibility.

Shipmates re-united. James Nixon (left) was one of many sailing friends who went aboard the Somme in Dublin to congratulate Michael d'Alton on his Legion d'Honneur. In 1964 they sailed together round Ireland in Euphanzel, and subsequently went to the Faeroes in the Excalibur 36 Tir na nOg. Photo: W M Nixon

Shipmates re-united. James Nixon (left) was one of many sailing friends who went aboard the Somme in Dublin to congratulate Michael d'Alton on his Legion d'Honneur. In 1964 they sailed together round Ireland in Euphanzel, and subsequently went to the Faeroes in the Excalibur 36 Tir na nOg. Photo: W M Nixon

1964 saw a last hurrah with Euphanzel with a round Ireland cruise, then the following year Ninian Falkiner was one of those who went with the modernising of Dublin Bay sailing, as he bought a brand new all fibreglass van de Stadt-designed Excalibur 36 which he called Tir na nOg. The mixture of local and offshore racing and extensive cruising which had become established with Euphanzel was continued, but after five years NInian and Mickey felt they'd done their duty by glassfibre, and the last boat for the team was the 12-ton Nicholson designed timber sloop Felise, which in 1970 they cruised to the Lofoten Islands in northern Norway.

With Ninian's death in 1972, Mickey became involved in partnership with a 25ft Glen OD, while his most notable cruising achievement during the mid '70s was as navigator for Paul Campbell aboard the latter's 37ft Tyrrell-built yawl Verve, which in 1975 they sailed out to Rockall where, from a dinghy rowed by Mickey, crewman Willie Dick, who had extensive rock-climbing experience, became possibly the first person - certainly the first yachtsman - to land directly on that tricky bit of rock, as any previous known landings had been by helicopter.

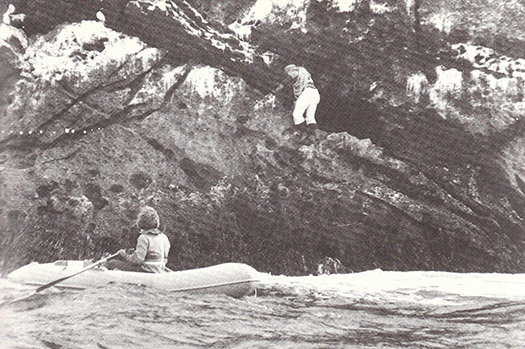

The Rockall landing in 1975 from Paul Campbell's Verve. Mickey d'Alton is manoeuvring the dinghy, while Willie Dick has just managed to grasp a handhold after jumping on to the rock face.

The Rockall landing in 1975 from Paul Campbell's Verve. Mickey d'Alton is manoeuvring the dinghy, while Willie Dick has just managed to grasp a handhold after jumping on to the rock face.

By this stage in life with his sixties approaching, Mickey d'Alton's sailing programme might have been expected to slacken. But war veterans cherish their freedom to go sailing as and when they please, and they cherish it far too much to think of easing off, let alone retiring.

So what is arguably the best part of Mickey d'Alton's sailing and cruising career was about to begin. He linked up with fellow senior sailors Franz Winkelmann and Leslie Latham, and they bought themselves a Ruffian 23 – Siamsa – which gave double value as she provided them with regular One Design racing in Dublin Bay, and thanks to modifications mostly made by Mickey – sometimes utilising unexpected items of equipment in unusual ways – she was turned into a very able little cruiser.

The Ruffian 23 Siamsa "airing out" during the 1997 cruise from Dublin Bay to the Isle of Scilly. Three very senior sailors managed to cruise thousands of miles in this very able if decidedly small boat.

And by heavens, how these three old guys cruised their little boat. It was all the more remarkable as Franz was all of 6ft 2ins tall, and more or less had to be folded in two if he was going to get below, while Leslie was so old his age was never mentioned. As for Mickey, his only concession to the passing years was that his vigorous hair and bushy beard were allowed even more freedom of movement and growth, and he looked like someone sent out from Central Casting to be the Old Man of the Sea.

The years may have been passing, but the enthusiasm for sailing never dimmed. Of their many cruises to many places, one of my favourites has to be the cruise to St Kilda in 1983. Siamsa's only auxiliary engine was an outboard so small it could only push them in and out of port in a calm, otherwise they were sail only, so in getting to St Kilda they dealt with headwinds simply by keeping sailing, and kedging in the nearest handy roadstead when the tide turned against them while beating through the Irish Sea and North Channel.

Maintaining a viable way of life in a 23 footer without standing headroom would have been a challenge to most sailors, but the crew of Siamsa just kept plodding along, they'd experienced it before, they knew they'd get there in due course, and meanwhile weren't they sailing and having a very satisfying time?

Still at it. Mickey d'Alton at the helm of John Latham's Beneteau Oceanis 311 Seasaw. Photo: Sonda d'Alton

Still at it. Mickey d'Alton at the helm of John Latham's Beneteau Oceanis 311 Seasaw. Photo: Sonda d'Alton

This remarkable partnership afloat lasted for well nigh fifteen years. In time Leslie passed on, then Franz died, yet although Siamsa was sold, Mickey continued sailing until quite recently with John Latham, Leslie's son, on his Beneteau Oceanis 311 Seasaw, while his love remains undimmed for the remote places best visited by cruising boats, and particularly the west of Ireland,

Until this week, Mickey d'Alton was best known as a sailing man, and in the world of sailing it was in the inner circles of cruising that he was most highly regarded. Over the years, his awards have included the Faulkner Cup of the Irish Cruising Club in 1956 and 1961, the ICC's Round Ireland Cup in 1964, and the same club's Wybrants Cup in 1983 and 1986, its Fingal Cup in 1990, and the Fortnight Cup – for a cruise to the Isles of Scilly in the little Siamsa – in 1997.

In addition, there would be a host of trophies from offshore races of varying lengths, and from inshore racing in Dublin Bay. And now, many years after receiving his medals won and presented during wartime, he is Legion d'Honneur and USV Distinguished Service Award. A great man.

Man of the west. Mickey d'Alton recently photographed in Roundstone in his beloved West of Ireland. Photo: Sonda d'Alton

Man of the west. Mickey d'Alton recently photographed in Roundstone in his beloved West of Ireland. Photo: Sonda d'Alton