#boatbuilders – In the good old days of bespoke boat-building, regular visits to the boatyard by the prospective owners were a sociable part of the process, regarded as normal and mutually instructive. And as most boats were built in waterfront premises beside slipways, or at the very least on a quayside, the first immersion was much more than just an informal splash from a convenient travel-hoist or a crane. On the contrary, it was the Launching Ceremony, a carefully choreographed festive event complete with the breaking of a bottle and sometimes even including the proper blessing of the new boat.

But nowadays, while such events can to some extent be staged, inevitably they have a certain artificiality. With transportation vehicles and roads improved out of all recognition, most production boats are now being built in factories at some distance from the sea - waterfront property is much too valuable to be used for basic industrial purposes.

As for seeing "your" boat being factory-built, you have to be up towards the top of the product range to be allowed that, and even then you mustn't bother the builders by talking to them. So the "launching" is simply a practical task carried out by professional marina staff with a minimum of fuss, for it has always been the case that when you just want to get on with a launching in a businesslike way, the last person you need around the place is the fretful owner.

Thus today's marine industry aspires to be the waterfront version of the car trade. Smooth, clean and impressive premises. Ready-to-go immaculate vehicles. And no hint at all of the need to get deep down and dirty in the building and maintenance of boats. But not every sailing and boat enthusiast is content with accepting such production-line techniques. W M Nixon takes a look at some of Ireland's invisible boat builders who cater for those owners who are different, and sometimes are doing it entirely for themselves. He also reveals the revolutionary Clontarf Contrivance, a Boon for Boatbuilders in classic style.

There are two Gods in the pantheon of Ireland's invisible boat-builders. One is Jimmy Furey, who creates exquisite classic clinker-built beauties to order in his tiny workshop in County Roscommon near the west shore of Lough Ree. And the other is Roy Dickson, who is incapable of sailing any boat without thinking of some way he'd like to improve it, and was a pioneer of the DIY dinghy-building movement in Ireland a very long time ago.

They're the Gods of our pantheon as both are now well into their eighties, and their influence has spread far beyond the shores of Ireland despite the fact that both are unassuming men who like nothing better than quietly getting on with the job.

But while Jimmy Furey is part of a long and distinguished Shannon tradition in that his innate talents emerged from working with his boat-builder brother Paddy, and are in turn being passed on to other master craftsmen such as Dougal MacMahon of Belmont on the western stretches of the Grand Canal, Roy Dickson is a complete one-off who is an inspiration to many, but you couldn't really say that there is a Roy Dickson School of Boat Re-Configuration.

Jimmy Furey quietly in action in his remote workshop in County Roscommon on the west shore of Lough Ree. Photo: Cathy McAleavey

The detail is a joy to behold. One of the transom knees in a Jimmy Furey Water Wag. Photo: Cathy McAleavey

The joy of Jimmy Furey's work is in the detail, so it's no surprise to learn that he turns his hand from time to time to being an award-winning model maker. But the beauty of his boats, whether they be Shannon One Designs or Water Wags, is of such a high order that you could say they're of international classic model boat standard while happening to be full size boats which can give a good account of themselves on the race course.

There is only so much work that any one man, however talented, can do, so it's encouraging to know that Dougal MacMahon is following the Furey way, his most recent job being restoration work with new planks and gunwhale, and re-installation of the centreplate casing, in Ian & Judith Malcolm's hundred-year-old Dublin Bay Water Wag in order for the boat to be fit to take part in next month's massive migration of the Wags to the big Morbihan festival in south Brittany. There, they will link up for the first time with the new French-built Water Wag, the product of Skol ar Mor which has been bought by Adam Winkelmann of Dun Laoghaire.

Dougal MacMahon of Belmont in County Offaly at the midway stage of this month's project to put a hundred-year-old Water Wag back into full health. Photo: Ian Malcolm

Having been looking at the new work on the Malcolms' Centenarian Barbara yesterday morning, rest assured that the Levinge/Furey style and quality is being upheld by Dougal MacMahon. Any good clinker-built racing boat will have a certain suppleness – indeed, it's said that one of the skinny Shannon One Designs will turn round and look at you when being driven to the utmost in a hard breeze. But with the Barbara, suppleness had deteriorated into sogginess. Yet less than two weeks of very concentrated work down in Belmont, with Dougal MacMahon as the master craftsman and Ian Malcolm as the gofer, has transformed the boat - there's new life in Barbara.

These days, Roy Dickson of Sutton is the doyen of boat building and modification through the use of modern materials. But as a recent celebratory lunch organized by his many shipmates past and present in Howth YC reminded us, in his astonishingly long career he did his duty and more by wood before bringing in various modern exotics. In fact, he started around 1950 with a Snipe called Bambi sailing out of the now defunct Kilbarrack SC on the north shore of Dublin Bay, whose demise began with its sailing waters inside the Bull Island being divided and made prone to silting by the construction of the fixed causeway across to the middle of the island.

Until that happened, KSC had a wonderful sheltered sailing area towards high water, as they'd a huge saltwater lake all the way to the Wooden Bridge. So they could get sailing even when conditions in Dublin Bay ruled out sailing at Sutton Dinghy Club itself. But soon enough, the young Roy Dickson had himself moved to Sutton, where he was Commodore in 1954, and he'd changed boats, building himself two Jack Holt-designed 16ft Yachting World Hornets – complete with International Canoe-style sliding seats for the crew - between 1954 and 1959, and racing them with success.

But as the best racing in Sutton was in the IDRA 14s, he built himself one of them in 1960, and then in 1961 he and Bunny Conn were in the forefront of the introduction of the Enterprise class, so that was his next command.

However, it wasn't until 1963 that all the Dickson stars came into alignment – the Fireball appeared. He was in there from the start – his first Fireball was No 38 – and with the class's flexible measurement system, the Dickson imperative for innovation had free range. And what he did was noticed by others. It's said that in his dozen or so years with the Fireballs, if some mod he made to his boat of the day proved beneficial, it would be done on every boat in Ireland within a week, and on every competitive boat in the world within a month.

As for Roy's sailing, he was competitive right up to world level, doing an early Fireball worlds in America with success with a youthful David Lovegrove, now President of the Irish Sailing Association, on the wire, with another Worlds in the Lebanon – God be with the days when you'd think of having a world sailing championship there – seeing one Bob Fisher as Roy's wireman.

Eventually, the Dickson campaigning moved into offshore racing with a succession of boats which, when combined with the possibilities provided by a variety of measurement rules, provided the artist with an enormous canvas to work with, and he was busy for decades. Most recently he has been best known for his stellar campaigns with the Corby 40 Cracklin Rosie and the Corby 36 Rosie, but we have to remember that by the time the boats left Roy's ownership, they were hugely different from the plans presented by John Corby.

The Corby 36 Rosie was the last boat to be campaigned offshore by Roy Dickson in a remarkable career which has included several Fastnets and Round Ireland races in addition to success in Cork, on the Irish Sea, and in the Clyde. He now races the Corby 25 Rosie in club events. Photo: Brian Mathews

Each winter, the boats would be trailed back to a special spot beside Roy's house, and unless you were in constant attendance you'd no idea of just how much tweaking and surgery was taking place. He brings his brilliant engineer's brain to the challenges of boat performance enhancement, and many are the specialists who experienced that special thrill of anticipation when they got a Monday morning phone call from Roy which simply opened with the statement: "I've got an idea".

For as sure as God made little apples, an utterly fascinating project would follow, and even if it involved hours of brutal hard work by volunteers – such as the shifting of the weight configuration in the keel-bulb on Cracklin Rosie – well, Roy is the kind of leader who inspires people to loyal service way over and above the call of duty.

These days at age 83, Roy's sailing wings are slightly trimmed as he campaigns his Corby 25 Rosie in club events, but the mark he made in sailing inevitably makes you wonder if there's any modern equivalent to the innovations of Roy Dickson in his prime, and your only conclusion can be that the modern version would have to be a marine industry professional. And at the sharp end of Irish sailing development, there's no doubt that Chris Allen of Bray is the man to go to if you want thinking and work way outside the normal box.

Yet though he works with completely state-of-the-art composites, Chris is in the finest tradition of the invisible boat-builder. Bray may be a seaside town, but his workshop is well away from the harbour, in fact it's alongside a rather pleasant little residential development in the heart of Bray beside the River Dargle. But the workshop itself is a decidedly basic and utilitarian sort of place where the space is shared with a car restorer, and as the car-fixer works with a giant oven while Chris works with a small one in order to achieve the temperatures their composites require to cure, the fact that the shed was freezing – and that on a sunny April day – was neither here nor there.

Graeme Grant and Chris Allen, the hidden boat-builders of Bray. Photo: W M Nixon

Chris's current project – on which he's working with Graeme Grant, Irish boat–building's favourite Scotsman – is building the very latest in the International Moths, complete with foils and a proven speed potential for normally competent dinghy sailors of thirty knots, while the sky's the limit speed-wise if you're a true ace.

{youtube}QlAzBoXy6g8{/youtube}

They've the tiny hulls and decks ready to go, but are being held up on completion by the late arrival of special components from various manufacturers. Meanwhile, they're busy with refining ever further the moulding of the struts which support the whole crazy caboodle of trampoline and rig and daggerplate and rudder and foil control, which means they're utterly absorbed in the sort of time-consuming task which would give any formal company financial controller the heeby jeebies.

The carbon hull of a Chris Allen Moth is exceptionally light........Photo: W M Nixon

.....and we mean REALLY light. Photo: W M Nixon

Chris Allen with moulds for the ultra-light struts for the International Moth. Photo: W M Nixon

But then Chris Allen's career path is scarcely along orthodox lines. He started his sailing on Lough Muckno in northeast Monaghan where his father – Dun Laoghaire sailor Hugh Allen, who had crewed with Alf Delany in the two-handed Swallow Class in the 1948 Olympics – had been posted as the Bank Manager in Castleblaney. Hugh Allen wasn't going to let the little dark hills of Monaghan end his sailing, so he built a Mirror and founded the White Island Sailing Club to race on the local lake, as he rightly reckoned that a Lough Muckno Yacht Club wouldn't quite do the business.

Subsequently he was posted to Moville in Donegal, and by this time he'd moved up to GP 14s, so we could argue that the current pre-eminence of Moville in Irish GP 14 racing goes right back to a former Olympic sailor being in the town. And it goes further than that, as the Allens' GP 14 was subsequently sold to a rising star in Dundalk sailing, one Pat Murphy......

Meanwhile, like many another young fellow, Chris Allen gave up sailing for ten years from the age of 18. He was into the music business, which isn't a sports-friendly way of life. But by the age of 28, sailing had hauled him back in again by way of Bray Sailing Club, and he was soon bring technical expertise to boats. Somehow or other, he ended up in New Zealand, and while his musical abilities were useful, his primary occupation was working with the innovative boatbuilder Cookson's, whose many successful creations have included Ireland's 2007 Fastnet Race winner Chieftain (Ger O'Rourke), a canting keel Farr 50.

For high tech boatbuilders, a spell working with Cookson's is the equivalent of a Harvard MBA for anyone who wants to rise in the corporate executive officer ladder. But back in Ireland, the corporate world is slightly more developed than the marine industry, and in hoping to use his skills honed in New Zealand, Chris Allen found he was building the hugely successful Velvet Glove for Colm Barrington in a shed in Enniskerry, and then when he came to build the arguably even more successful Ker 32 Voodoo Chile for Eamonn Crosbie, he'd found his current hidden premises in Bray.

The glassfibre Mermaid Dolly (right) was a lovely piece of work by Chris Allen, but in the end the class decided to stay with timber construction.

His enthusiasm remains undimmed, as too does his readiness to express firmly-held opinions on boat-building of all kinds. But his skill in his specialist area is unrivalled, and he can be as versatile as any boatbuilder. Thus he was the man to go to in the days when the SB3 – then in its first incarnation as the SB20 – was experiencing a certain amount of teething problems. But equally, when Roger Bannon wanted to experiment with a GRP version of the Mermaid, he quite rightly reckoned that Chris Allen was the man to go to, and the result was one of the sweetest clinker GRP boats you'll ever see, even if the class in its wisdom decided eventually to stick doggedly with wood.

As we were in Bray, there'd been a hope of going on to see the two new Bray Droleens as they near completion, but in this case the invisible boat-building remained utterly invisible. The project is currently on hold while the workshop undergoes a renovation project, and the pair of little boats are temporarily in store in a shed whose key-keeper happened to be in the other end of County Wicklow. But nevertheless it's good to know that Anthony Finnegan and his team have continued the fine work started by the late Frank de Groot, and congratulations to Jim Horgan of Furbo on the south Galway coast, whose re-creation of a Droleen was recently awarded one of the Classic Boat Trophies in London.

Jim Horgan sailing his award-winning Bray Droleen in Connemara

It was far from the world of classic boats that the next item on our North Wicklow agenda lay, as we were working on the ancient Chinese principle that seeing something once is worth hearing about it a hundred times, and we were determined to see for ourselves if the new multi-functional maritime clubhouse really is being built beside the re-developed harbour and marina in Greystones.

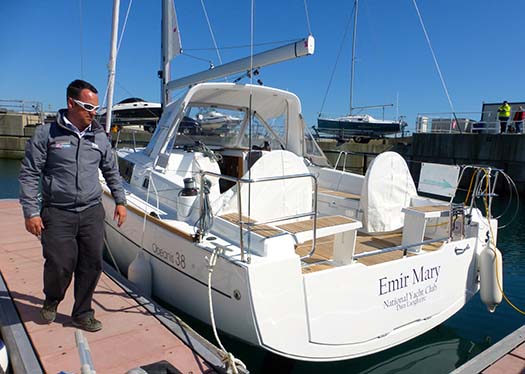

So, having been immersed for the morning in the hidden marine industry, that afternoon we had the modern marine industry in its most visible form. For although the new clubhouse is as yet barely above ground, it is definitely being built. And nearby at the marina, James Kirwan and the team in BJ Marine were in hospitable form on a perfect sunny day with a steady stream of seriously interested visitors coming to see fully finished yachts in showroom condition. It was like a different planet, and we much enjoyed a conducted tour of a spanking new Oceanis 38 which has been prepared and laid out for a Dun Laoghaire owner who is quite clear in his own mind that he only intends to use the boat for day-sailing and hospitality purposes.

The way we live now.....James Kirwan of BJ Marine with a new ready-to-go Oceanis 38 in Greystones Marina. Photo: W M Nixon

Believe me, with the sun shining down and James Kirwan enthusing about the success of the new BJ Marine linkup to the Snowdonia Riviera on Tremadoc Bay with their latest office in Pwllheli in North Wales, you could be very easily seduced into availing of all the ready accessibility of today's front-line marine industry if you just happen to have the magic ingredient of enough money. But for most of us still spluttering our way out of the deluge which was the recession, it's a matter of making do as best we can.

And for others, the shiny new boats are not the way to go at all. On the contrary, they want to experience traditional hands-on lovingly crafted boat-building for personal fulfillment as much as having a boat at the end of it, and out the back of Clontarf Yacht & Boat Club there's a kind of Men's Shed operation convened by Ronan Melling which has been building a classic IDRA 14 for quite some time now, but the results show that they're willing to learn, and nothing is too much trouble to achieve perfection.

And now the tricky bit.....a spot of concentrated thinking under way last November as the Clontarf team grapple with the challenge of steaming and installing the frames in their new IDRA 14. Photo: W M Nixon

It's also the very essence of the invisible boat-building spirit, as they're only in action on specific nights for work spells of set duration. But on a first visit last November when you could already see that the planking work was of the highest quality, they'd got to the crucial stage of putting in the first steamed frame, which with all the hassle of keeping a steamer up to heat, is quite a step for an amateur team.

But they persevered despite having problems with several types of steam boxes, and then somebody had the wonderful idea for the Clontarf Contrivance. Somehow they made the leap from thinking how steaming a frame is a matter of keeping up pressure to the notion that a bicycle tyre is also a matter of keeping up pressure. The inner tube from a bicycle tyre, with a bit of another inner tube added for the required length, will neatly accommodate the complete frame for an IDRA 14. All you need to do is put the steam into it under the optimum amount of pressure. It has worked, for as the most recent photos show, the task so tentatively begun last November is now complete with as neat a framing jib as you could hope for.

As neat a job as you could wish. The new IDRA 14 with the frames in place.

The secret weapon. We all know what a bicyle inner tube looks like, but have you ever thought of it as the Clontarf Contrivance for steaming frames for clinker-built boats?

The spirit of doing it for yourself is if anything even stronger along Ireland's western seaboard, and back in SailSat for the 29th March 2014 we featured – among many other boats – the Atkins schooner which the great Jarlath Cunnane was building for himself in Mayo in anticipation of the eventual sale of his Arctic Circle-girdling Northabout.

Well, Northabout has now been sold and will be going to the Antarctic as an expedition boat, but meanwhile last Autumn I grabbed a quick photo of the new schooner finally out of the building shed (which for once actually is a waterside shed), and we look forward to seeing her afloat and in action.

Shaping up nicely. Jarlath Cunnnane's new alloy-built schooner. Photo: W M Nixon

Far to the south along the Atlantic seaboard, and up the winding Ilen River above Baltimore you'll find Oldcourt and the Old Corn Store where the restoration of the Conor O'Brien ketch Ilen is moving steadily along. But as the Ilen project is ultimately Limerick based, the fine premises in Limerick where Gary MacMahon and his team built both the traditional gandelows and the CityOne dinghies provides an excellent workshop for building the more detailed parts of Ilen, and this week Gary circulated a photo of the deckhouse which will go above the engine room, and very well it looks too.

Ilen's new engine room deckhouse, workshop-built in Limerick. Photo: Gary MacMahon

For in winter, there is nothing more conducive to getting jobs completed than having adequate resources and a clean and comfortable workshop where you've a bit of space to go about the project, which so often is not the case for Ireland's hidden boat-builders.

But they do things differently in other places. Back in SailSat of February 7th this year, we ran a piece which included news about a restoration project which is under way with a specialist company in Palma in Mallorca, giving new life to the 37ft Fife-designed Belfast Lough One Design Tern of 1897 vintage. We published a photo of Tern as she was in July 2014, striped off and ready for the work. On Thursday, I received two photos of Tern being launched on Wednesday after nine months work. Just to show what has been achieved, we start with that photo of Tern in July 2014. Further comment is superfluous.

Tern as she was in July 2014.

Tern as she was last Wednesday, test launching in Palma.

Work of the ultimate quality. Tern's new bronze deck fittings are probably worth more than the boat herself was when she was built to a fairly basic specification by John Hilditch of Carrickfergus in 1897.